Winn Collier's Blog, page 42

May 3, 2012

Shoo, Bird, Shoo

The birds are back.

One small but inordinately vocal (and tenacious) feathered species has apparently added the Collier house to its Spring Virginia tour. Without making reservations but with plenty of brass, the little buggers annually descend on our alcove and set up house. Their intentions are focused: to mate and nest. I don't begrudge them their space; and I certainly agree that, given our stellar view of the Blue Ridge, it's a romantic spot for getting your groove on. However, we have a history now, and we've proven this doesn't end well.

It would be disingenuous of me not to confess that cute as they are, these birds are a pain in the tooshie. Their incessant, shrill chirping makes you want to gouge your eyes with a hot poker. Then do it again. A lovely birdsong is one thing. This sharp, metallic chorus is another thing altogether. And the shit, oh the shit – it's astounding the amount of mess a couple tiny birds can unload. If that ratio held for humans, I can't begin to fathom what changing diapers in our house would have been like.

Besides the noise and clops of poo and the other filth the birds bring, there are altruistic reasons why I've decided that this time the birds can't stay. One year, a young toddler son (whose mother, by the way, had repeatedly told him to keep his grubby paws off the eggs) tried to sneak a small white pearl into his bedroom. He had lined a box with grass and twigs and hid it under his dresser. He wanted "to help the birdie grow." Needless to say, the bird did not come of age. Another year, our dog pounced on a nestling just after she cracked through her shell. Our boys are still working through the trauma. I could go on.

The cruel truth is that our house is not a gentle haven from which mommy and daddy bird can succor new life. Mere feet away from their chosen perch, we have a lush, sturdy tree they can inhabit, and I'm happy for them to do so. Only, not on the porch. Not this year.

But these birds refuse to take no for an answer. Yesterday morning, I pulled out the ladder and cleaned out the beginnings of their 3 bedroom / 2 bath build. A couple hours later, I looked out only to see fresh foliage had returned. This has happened six times so far. Six times I've cleared out their sprigs, six times they've packed them back in. These chirpers are watching me, feathers crossed over their chest, saying, Listen, pal. I can do this all day.

The story that keeps playing in my head is Jesus' parable of the widow who hounds the unjust judge until he caves and hands the woman her request. Since my options for characters I could play in the story are slim, I don't care to draw too many parallels. However, I do find my resistance wearing thin.

April 30, 2012

Love’s Whistle

One of my great disappointments in life is that I can't whistle. I can make some strange tinny noise while sucking in air, but it's a wimpish tone, with no bellow to it. And since I can only muster this neutered note while while gathering air, my chirp only lasts 10-12 seconds before I'm gasping for breath. It's embarrassing, particularly when your sons want you to teach them the licks. I still believe whoever whistled that opening for the Andy Griffith Show is a god.

My dad, however – now he can whistle. When I was a kid, he'd tootle the usual tunes when a melody stuck in his head, but mainly my dad whistled to communicate. Whistling is dad's fourth language. A true linguist, dad has four primary tongues: English, Texan, sign language and whistling. Sign language was for when we were in a public setting and dad wanted to say something off the radar. It may have been as simple as granting me permission to exit church and go to the bathroom — but receiving confirmation via clandestine hand code made the whole thing excitingly cloak-and-dagger. Whistling, however, was the opposite of covert; whistling was for those occasions when dad wanted to make sure he reached ever nook and cranny of the neighborhood. Dad had a powerful, looping whistle, and it signaled time to return home for dinner or chores or for an outing. That whistle was unmistakable. Dad could be a couple blocks away, and I knew exactly what it meant and would come running.

I loved the sound of that whistle. I hear it now. That powerful echo told me that there was a place called home and that there was a dad standing there at the front steps waiting for me.

St. John speaks of God as our shepherd and we the sheep. And the sheep, John says, know the Shepherd's voice. We know the whistle. John doesn't have much to say regarding our tenacious efforts to hear, preening toward every scrap of sound while anxiously deciphering its meaning (or not). John simply says the Shepherd speaks, and the sheep hear. And then the sheep follow. Of course, we could rightly protest with the hundred competing scenarios where things go differently, where the Shepherd seems difficult to hear – or where the sheep don't listen or don't follow. But of course, John doesn't say the sheep hear everything plain. We simply hear enough. We hear plain whatever we need to hear plain. That's the rub. Ever since Eden, we tend to believe we need more knowledge than we actually do.

But all we really need to know is the whistle. And to know that a Father filled with love waits for us at the front steps.

April 26, 2012

Those Sneaky Poems

Being National Poem in Your Pocket Day, today is the moment for letting words rather than the spare coins jingle in your pants or your purse or wherever you stuff things you want to carry with you for the day's adventure. I once thought poems as merely something that rhymed. However, because I've been given the good grace to have a wife and a couple friends who are poets – and because I've been knocked sideways by more than a few metered lines – I now know poetry to be more than repeating words finished with -ing. Poetry teaches us how to see and how to hear, how to observe and how to speak.

Poetry insists we watch for delicate distinctions, fully aware of how meaning can turn on the difference between a finch and a sparrow. Poetry coaxes us to nurture memory, aware that if we've forgotten old Moses terrified when the desert shrub struck flame, we won't encounter this splendid awesomeness when Whyte speaks of "the man throwing away his shoes / as if to enter heaven." Poetry provides us a language that's as much about discovery as it is about stacking up facts. Of course, we'd have chaos if our tax forms were arranged in poetic verse, but wouldn't we have coldness and sorrow if our lovers and friends and our walks in the woods didn't play in things poetic?

Yesterday, Wyatt was discussing the Avengers, which led to a conversation about favorite superheroes. Wyatt ran through the list, outloud as he does. Noticing a pattern, he made an observation: "I don't really like girl superheroes. Well, I do like Cat Woman."

"Why?" we asked.

"I like Cat Woman," Wyatt concluded, "because of all the sneakiness."

That's one of the big reasons I love poetry: because of the sneakiness. Poems have a tendency to catch me when I'm dozing. They seem so docile there on the page, short and tidy, all mannered and in neat rows. And then that one line or phrase – a single word sometimes (syllable even) – and my head's buried in my hands or my heart's ripped wide.

It probably seems plain enough why my writing self would love poetry so. However, does it strike you as odd to say that poetry affirms something about why I love the work of pastoring and the study of theology as well? To pastor, as I see it, is to be a resident poet, a poet for the parish. A pastor works his poetry amid the subtleties of babes and grandfathers, treacheries and joys, noting all the while that a sparrow is not the same as a finch. With this, studying theology (a curious attentiveness to God's story) is to ask questions and listen for nuance and sweeping themes pregnant with possibilities. As Marilynne Robinson says, "Great theology is always a kind of giant and intricate poetry, like epic or saga." If our Christian teaching doesn't play well with poetry, we have most likely identified a problem.

If all this is true, then we are desperate for poets, poets of every sort. We need women and men who live attentive to the life about them, their work and their family – which is to say, their art. We need brave and imaginative souls who see and hear and then help us see and hear. "The most regretful people on earth," says Mary Oliver, "are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave it neither power nor time." I think she's right. Give it power and give it time. Please, for all of us.

April 23, 2012

Our True Selves

Strange the things one discovers about himself, unsuspecting. For years, I've believed I delivered a rather authentic, if not bemusing, British accent. I've considered it one of my subtle skills. It's not something you'd know about me. A fellow doesn't go around broadcasting such a thing unless he's a crass braggart. On random but not irregular occasions, I'll toss, mid-conversation, my best old English chap voice. I've been buoyed by the fact that it always provokes laughter from my two boys, leaving them begging for more. This corroboration has been perhaps misguided. I shouldn't be surprised, given that their comedic palette hasn't exactly come of age. They still ;howl over anything from a knock-knock joke to any use (any use whatsoever) of any word (or sound) connoting a bodily function. Yet these were the two I relied upon to validate my impersonating talents.

This weekend, Miska and I were chatting and laughing, and I thought it a good time to up the ante by kicking in my British accent. I landed the line and waited for the laughter to follow. There was no laughter. Instead, Miska, with an expression somewhere between bewildered and pained, asked, "What was that?"

"It's my British accent." I answered, flustered. "Of all my accents, it's one of my better ones."

"Winn," said Miska (and her tone would have been no different if she were informing me that in fact, no, I couldn't fly to the moon), "you can't do a British accent."

I protested that I've provided a good British impersonation for years, but she only shook her head no. "Winn, the only time you've gotten that right is when you've attempted an accent from another country – and it comes out sounding British instead."

Painful. But it's good to know these things. In St. John's gospel, we happen upon another good but painful moment. John offers a beautiful line, narrating how many people heard Jesus and were caught up with Jesus' message and life – and how they "entrusted their life to Jesus." However, in one of the more jarring moments in the Bible, John tells us that Jesus did not reciprocate. Jesus did not entrust himself to them because he knew them. Jesus knew their deep heart, the place deeper than what one can know by what we see or hear.

Some read this text as a reference to Jesus' eternal acceptance or rejection of these would-be followers — in other words, they read this as a question of ultimate destiny. I don't hear it that way. I think Jesus simply knew that there are people who can be trusted and people who can't, at least not yet. Many people think they know themselves, but they've barely begun that journey. It's best not to hand your heart over to one who hasn't yet learned how to handle their own.

What Jesus did (with remarkable mercy) do was give his full self for those he was unable to trust, all in hopes of making us to be the very ones in whom he would eventually entrust his entire life, Spirit and love. But first came the rejection, the cross, the truth of how much within us needed to be made whole, made trustworthy. We must discover the truth about ourselves; and then we can be loved into ourselves, our true selves.

April 19, 2012

Be is Way Better than Not-Be

When I found my tracks in the snow

I followed, thinking that they might

lead me back to where I was. But

they turned the wrong way and went on.

{Kooser and Harrison}

When we think of the questions we ask children when first getting acquainted, children of friends or neighbors or co-workers, it's typically a bland and predictable litany. Do you like school? Are you ready for summer? What games or sports do you enjoy? What do you want to be when you grow up? It's a wonder kids don't write us adults off as imbeciles, with our dim-witted conversational imagination.

My dad, ever a kid at heart, used to ask a child how old they were. It was a ruse allowing my dad to land one of his favorite jokes. It went like this:

Dad: So, how old are you?

Kid: 7

Dad: Really? That's great. When I was your age, I was 8.

Worked every single time. The child was always bewildered, but at least she wasn't bored. This curve ball provided a welcome surprise and the excitement of going off script.

Of course, asking a child – or a grown man for that matter – what they'd like to be when they grow up can invite a wonderful conversation that explores hopes and possibilities and fears, the things we might be too timid to admit if we're sticking to standard repartee.

However, at some point (and I wish we could locate this precise point and blow it to smithereens), we cease living with a roused imagination of what could be and we commence a life defined by an austringing vow of what we will never, ever be. We are wounded and angered by another's imperfections. A parent, sibling or friend shatters our emotional cocoon, our naiveté. Some of us suffer a thing far more vile, something that must be named evil. Others of us run up against the dark or embarrassing side of a community or a system we had once accepted uncritically. We feel duped, disregarded or mauled. Even more perilous, we learn to hate something about ourselves, something we've come to believe is too foolish or too simple or too sensitive. We've been dismissed or scoffed, and we vow never again.

In response (consciously or unconsciously) to these disorienting experiences, we promise to never be that. Ever after, far too much of our energy and far too much of our person exists in reaction to whatever that represents.

Living in reaction to something means that this something defines our questions and our direction; it sets the parameters of possibility. Our vision shrivels to a myopic little square. Your life deserves far more than a square. If we fix our attention on what we're leaving, we'll never have a wide view of the vast terrain stretching ahead. Instead, we'll just keep looking back, and we're bound to only walk in circles, a loop with arcs round that single story. We can never forget (nor should we try) what we're leaving. It's part of us. For good or ill, it helped to make us. Along the way, we may even come to see some of our experiences in new, mature light. However, the past is only one fraction of who we become. There's so much becoming yet to do.

A good and courageous and free life won't be lived when you're trying to not-be. You have to be. Take whatever truths or scars your story has handed you, take them in and listen to them. And then go discover new ones.

In the Bible God enjoyed giving people new names. And these new names had little to do with whatever they were leaving and much to do with where they were going.

April 16, 2012

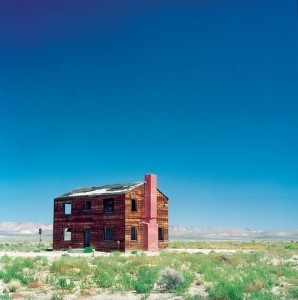

Rust Gets a Shine

When we moved to Charlottesville, we hoped for an old house in an old neighborhood. We didn't want a fixer-upper (anyone who knows me knows what a disaster that would launch), but we wanted something with scuffs in the wood floors and a couple good creaking spots in the staircase and a grand front door with a large stained-glass window gathering the sunlight and streaming the rainbow shafts into the foyer where, in warm months, we'd welcome all our friends with glasses of wine and Miska's yummy hors d'oeuvres. We hoped for a yard with green grass, grass that had reached into that plot of soil so long and deep that it owned the place. We were simply guests. We wanted trees with kid's names from numerous decades scratched into the bark, trees with sturdy barrel-sized branches to undergird the fort we'd build for the boys.

Unfortunately, our dream outstretched our pocket book, and for some odd reason the bank wanted to hand us a loan they thought we could actually repay. We do love the house that's become home. Still, we have flashing fancies of living in something old, something old that is – with love and care and joy – made new again and again.

When I was a kid, I mocked the so-called rust belt cities. I believed them to be used up and burnt out. I was ignorant. Now those very places, like Detroit, Pittsburg and Cincinnati, fascinate me. I gobble up their stories. I'm eager for all the signs of renewal. They say that in some Detroit neighborhoods, you could buy up a block for the price of a single dwelling in a major East Coast town. My, wouldn't that be fun – the chance to grab a few friends and resuscitate an entire city block.

This instinct, to breathe new life into old and discarded things, is an expression of Easter hope. Resurrection does not announce a creation ex nihilo. Something out of nothing happened once, at the origins of our cosmos. Ever since, creation always comes from something, out of something. Jesus’ body came back to life – he wasn't granted a new one. Still evidencing the scars from his wounds, Jesus’ body, his old tissue and his old bones, were made perfectly new. This is how God breaks resurrection loose everywhere. God's New Creation, inaugurated in Jesus, takes ramshackle villages and ramshackle stories, tired words and tired souls, limp hopes and limp hearts – it takes all those things that are used up and rusted out and announces: Rise up. Live.

April 12, 2012

Common God

Earth's crammed with heaven,

And every common bush afire with God:

But only he who sees, takes off his shoes,

The rest sit round it, and pluck blackberries

{Elizabeth Barrett Browning}

Last week, Wyatt was exasperated. "Dad, you don't hear lots of things." I protested, but he appealed to Miska for backup. "Mom, dad doesn't hear a lot of things I say, does he?" I'd like to report that Miska, the one to whom I've pledged my life and love, the one who is my very flesh, shut this inquisition down cold. However, Miska is committed to the truth, blast her. My defense – what I wished to say but did not – is this: the reason I might miss miniscule tidbits from Wyatt (here and there, on the rarest of occasions) is because Wyatt says a lot. Wyatt, like his father, is a verbal processor which is to say that words, abundant words, gush from the spigot. Why speak three things when you can speak fifty?

It's too easy for me to miss Wyatt's voice (which, I'm sad to say, means missing him) because at times it's everywhere. Having grown accustomed to the ubiquitous sound, I tune it out and mentally traipse off to god knows where.

After reading one of the Bible's more electrifying stories (say, the Red Sea opening wide for Israel or Jairus' daughter regaining life), I'm often vexed because I've never experienced anything of the sort. I haven't seen God do this stuff, I worry. So have I ever seen God at all? Hauerwas says that "we [don't] see reality by just opening our eyes." True enough, but we also won't see reality by keeping our eyes shut. Our vision is off-kilter, and we need to learn how to see clearly. But to see something, we've got to be looking in the first place.

And if we seek, we shall find. We will find the God who holds the very world together, the one in whom all joy and creative energy and holy silence exist. God's life is pregnant in the delight I encounter with my sons and in the way my imagination expands toward those mysterious mountains I've known so long. God occupies the truths that have grabbed me and refuse to let me go. God rests in the quiet spaces that call me forward and inward. God chuckles in my laughter. God seeps from the pages of my many hardbound companions. God exists in the fierceness that eventually rises against my fears. From one astounding woman, God has spilled copious measures of pleasure and deep knowledge and love, love and more love.

We miss God, not because God is so hidden but because God is so common. Blackberries are scrumptious — but by God, man, the bush is aflame.

April 9, 2012

Spark

We have a cat in our house. I've never been fond of these coy creatures who strut about like they own the joint. However, Wyatt loves cats, and I love Wyatt. So on Wyatt's ninth birthday, we adopted a felis catus that had been abandoned in a cardboard box on the doorstep of our local vet. They couldn't nail down the cat's age, but she is well beyond kitten. They pulled most of her teeth, rotted as they were. We have no idea of the cat's original name, which was welcome news to Wyatt because this meant he could pick a new one. For a boy, naming your pet is half the reason for having a pet at all. We purchased a litter box and a couple toys and new feeding dishes. Spark took up residence in Wyatt's room, settling on Wyatt's bean bag as her nest and perch.

We assume Spark has abuse in her background. She was skittish her first months in our home. In high school, a friend spotted a cat sunning on the sidewalk where we walked. He snagged the feline by the tail and twirled her, screaching as only a terrorized cat can, above his head in large, looping arcs. At the height of one of his whirls, he released the cat, catapulting the shrieking projectile toward the roof of a building near us. She survived the ordeal, but all that to say that the world can be cruel to the Sparks among us.

The beauty for Spark is that she's found herself a Wyatt, a boy who will hug her and talk to her and who would surely punch in the nose any ruffian who intended to toss her on a roof. Some mornings, Wyatt will come downstairs with his t-shirt covered in white cat hair, proof of all the play and love he's pouring on that little creature who has now found a place to belong.

Each of us have a bit of Spark in our story. And, I pray, everyone of us has a Wyatt.

April 5, 2012

God’s Shape (upon holy week)

If you are a man with roots than run South (or Southwest, as in my case), then chances are that cornbread claims a sacred place, alongside other relics like grits, football and music with a twang. My grandma made cornbread (straight, not sweet) in cast iron skillets, the kind with decades of grease massaged into every crevice. On special occasions, she would go more elaborate and pull out a cast iron sheet with small molds of corncobs cut into the pan. Dinner offered a basket overflowing with piping hot, individual sized loaves of cornbread. The bread looked cute, all sitting there dressed up like corn freshly shucked; but we knew what it really was – and we were eager to dive in.

When we hear the word form, we often think of something like that. A form is the shape of something, but it may or may not have congruence with what's actually inside. However, the Bible's word for form means something more. In Scripture, a form is the outward visibility of something's true inner quality. In other words, St. Paul would say that the form of cornbread looks like cornbread. And oh how we could play with that image for a bit.

Imagine then what the Scriptures mean when they tell us that Jesus was "in the form of God." We read this little section of Philippians, electric with all its mystery and possibility, each year at the beginning of Holy Week, the week we find ourselves in, the week when Jesus does the absurd, the week when God dies. Apparently, God has a form. Only, for the first bulk of human history, humans had not been able to see that form. We didn't have the capacity for such a vision.

Until Jesus. The scandal of Paul's words is not the assertion that Jesus is a good human presenting to us a model of God-like life or even that Jesus is a good human who also happens to be Divine in some impossibly mysterious way (though Jesus was human and was divine and it is mysterious). Rather, Paul announces that Jesus is what God looks like when God goes physical. Jesus acted as he did and lived as he did because this is the way God lives and acts. If God was to be humanly visible, then Jesus was the necessary expression. Sometimes you can tell a book by its cover.

Jesus did not go to a cross and suffer humiliation to illustrate some other truth about God or to exert unthinkable energy to finally get our attention. Jesus certainly did not surrender his entire being as an act of appeasement to twist a begruding Father's arm toward mercy. This is the daring claim: Jesus is what God looks like when God takes human shape. When God goes visible, then God lays down his life for others. God does not exploit what is rightfully his to exploit. God surrenders himself for the sake of love.

Stanley Hauerwas, resisting sentimentalized visions of Jesus' passion, warns of the "bathos [which] drapes the cross, hiding from us the reality that here we first and foremost see God." If we want to know what God is like, we look at Jesus, walking the via dolorosa, the way of grief and suffering.

The shape God takes, the shape love takes, is cruciform. God's form is Jesus, suspended on a cross, crying out for the healing of the world.

God's Shape (upon holy week)

If you are a man with roots than run South (or Southwest, as in my case), then chances are that cornbread claims a sacred place, alongside other relics like grits, football and music with a twang. My grandma made cornbread (straight, not sweet) in cast iron skillets, the kind with decades of grease massaged into every crevice. On special occasions, she would go more elaborate and pull out a cast iron sheet with small molds of corncobs cut into the pan. Dinner offered a basket overflowing with piping hot, individual sized loaves of cornbread. The bread looked cute, all sitting there dressed up like corn freshly shucked; but we knew what it really was – and we were eager to dive in.

When we hear the word form, we often think of something like that. A form is the shape of something, but it may or may not have congruence with what's actually inside. However, the Bible's word for form means something more. In Scripture, a form is the outward visibility of something's true inner quality. In other words, St. Paul would say that the form of cornbread looks like cornbread. And oh how we could play with that image for a bit.

Imagine then what the Scriptures mean when they tell us that Jesus was "in the form of God." We read this little section of Philippians, electric with all its mystery and possibility, each year at the beginning of Holy Week, the week we find ourselves in, the week when Jesus does the absurd, the week when God dies. Apparently, God has a form. Only, for the first bulk of human history, humans had not been able to see that form. We didn't have the capacity for such a vision.

Until Jesus. The scandal of Paul's words is not the assertion that Jesus is a good human presenting to us a model of God-like life or even that Jesus is a good human who also happens to be Divine in some impossibly mysterious way (though Jesus was human and was divine and it is mysterious). Rather, Paul announces that Jesus is what God looks like when God goes physical. Jesus acted as he did and lived as he did because this is the way God lives and acts. If God was to be humanly visible, then Jesus was the necessary expression. Sometimes you can tell a book by its cover.

Jesus did not go to a cross and suffer humiliation to illustrate some other truth about God or to exert unthinkable energy to finally get our attention. Jesus certainly did not surrender his entire being as an act of appeasement to twist a begruding Father's arm toward mercy. This is the daring claim: Jesus is what God looks like when God takes human shape. When God goes visible, then God lays down his life for others. God does not exploit what is rightfully his to exploit. God surrenders himself for the sake of love.

Stanley Hauerwas, resisting sentimentalized visions of Jesus' passion, warns of the "bathos [which] drapes the cross, hiding from us the reality that here we first and foremost see God." If we want to know what God is like, we look at Jesus, walking the via dolorosa, the way of grief and suffering.

The shape God takes, the shape love takes, is cruciform. God's form is Jesus, suspended on a cross, crying out for the healing of the world.