Nancy Adams's Blog, page 6

February 20, 2014

Magnus Bane and Lord Akeldama: A Meeting of Minds (second in an occasional series)

photo from Steve Allen’s website (click for link)

Just as Steve Allen’s TV show from the 1970s, A Meeting of Minds, brought together greats separated by time and geography, enabling Cleopatra, say, to chat with Thomas Paine, Teddy Roosevelt, and Thomas Acquinas (1st episode), I have often fancied the idea of bringing together fictional characters from different authors, enjoying the thought of their virtual tea parties.

Take Magnus Bane and Lord Akeldama, for instance, the delightful and ultimately endearing characters from (respectively), Cassandra Clare‘s Shadowhunter universe and the steampunk world of Gail Carriger‘s novels. Both are immortal, gay, and sartorially savvy.

Magnus is a warlock (an immortal being in Ms. Clare’s universe), whom we first meet in the modern world of New York City where he gives lavish parties and enjoys dressing in flamboyant outfits. When he meets handsome Shadowhunter Alec Lightwood, however, he falls seriously and hard. In Ms. Clare’s Shadowhunter world, warlocks are considered “Downworlders”—disdained by Shadowhunters like Alec and his family as outsiders at best, enemies at worst—so the smitten warlock has an uphill battle finding acceptance, let alone love. Magnus also appears in the parallel prequel series beginning with Clockwork Angel, which is set in a steampunk Victorian London.

Magnus is a warlock (an immortal being in Ms. Clare’s universe), whom we first meet in the modern world of New York City where he gives lavish parties and enjoys dressing in flamboyant outfits. When he meets handsome Shadowhunter Alec Lightwood, however, he falls seriously and hard. In Ms. Clare’s Shadowhunter world, warlocks are considered “Downworlders”—disdained by Shadowhunters like Alec and his family as outsiders at best, enemies at worst—so the smitten warlock has an uphill battle finding acceptance, let alone love. Magnus also appears in the parallel prequel series beginning with Clockwork Angel, which is set in a steampunk Victorian London.

Steampunk Victorian London is also the milieu where we first encounter Gail Carriger’s Lord Akeldama, a vampire whose personality smartly blends Wooster and Jeeves—Bertie on the surface, but a mind like a steel trap beneath. Given the avowed influence of P.G. Woodhouse on Ms. Carriger’s delightful fiction, it is not a surprising combination. Beneath Lord A.’s constant frivolous banter resides one of London’s most powerful movers and shakers.

By the end of each series’ first book, Magnus Bane and Lord Akeldama have easily evolved into this reader’s favorite series characters. Each appears first in his surface persona—smooth, urbane, perhaps shallow—then rapidly proves his worth in sticky situations, helping the series protagonists at serious personal and professional risk. As the books continue, we see the vulnerabilities and pathos of each character, vulnerabilities deeply concealed beneath the armor of clothing and manner. Their gay orientation adds to the poignancy and pathos of the outsider status already dictated by their natures as vampire and warlock.

Wouldn’t it be delightful to bring the two of them together for a Victorian vampire-and-warlock tea party? Just imagine the witty conversation—and the personal entanglements. Would Magnus overcome Lord A.’s broken heart? Or would the two of them end up as platonic allies? Wouldn’t it be interesting to combine Gail Carriger’s steampunk folks with Cassandra Clare’s Shadowhunter characters?

Ms. Clare’s more recent series of e-stories, The Chronicles of Magnus Bane, shows that I am not the only reader to come away from the series with Magnus as one of my favorite characters. Since The Chronicles of Magnus Bane are being published only in e-format and I have yet to purchase an e-reader (decisions, decisions!), I am ignorant of his further adventures, yet I am glad to have them to look forward to.

Ms. Clare’s more recent series of e-stories, The Chronicles of Magnus Bane, shows that I am not the only reader to come away from the series with Magnus as one of my favorite characters. Since The Chronicles of Magnus Bane are being published only in e-format and I have yet to purchase an e-reader (decisions, decisions!), I am ignorant of his further adventures, yet I am glad to have them to look forward to.

Likewise, I hope to visit Lord Akeldama again when Ms. Carriger’s new series featuring her original protagonist’s daughter comes out later this year.

Meanwhile, here’s to both authors for giving us such rich and memorable characters!

[image error]

photo from Gail Carriger’s blog Retrorack, where she indicates that this would be suitable attire for Lord Akeldama

(Click image to link to blog)

Filed under: Books Tagged: Cassandra Clare, fantasy fiction, Gail Carriger, Lord Akeldama, Magnus Bane

February 13, 2014

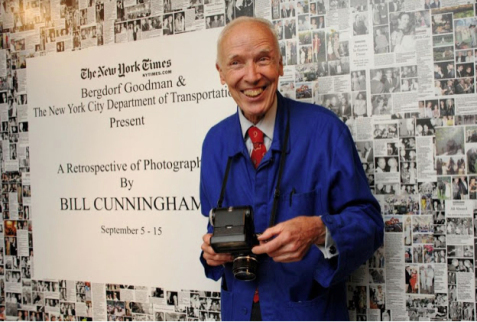

Bill Cunningham

Anyone who knows me face-to-face knows that I’m as far from a fashionista as it is possible to be. I dress for comfort, wearing the same sets of clothing week after week: cords/jeans, knit top, and usually a sweater, in a color range chiefly confined to black, brown, blues, and greens. But recently I watched a film on fashion photographer Bill Cunningham which touched me deeply: Bill Cunningham New York (directed by Richard Press, 2010).

image from mochigrrl.blogspot.com

For over 30 years, Bill Cunningham has produced the weekly New York Times feature “On the Street.” As the title suggests, Cunningham’s work chronicles in photographs the street life of the great city, typically organized around a common sartorial theme. Each week’s theme arises naturally out of Cunningham’s observations, something that suddenly seems omnipresent to his trained but impartial eye: things such as a particular T-shirt graphic, a certain color, a distinctive style of shoe that everyone seems to be wearing.

While his subjects include fashionistas, celebrities, and socialites, Cunningham’s lens makes no distinctions of class. His modus operendi is to simply photograph whomever happens to strike his eye, whether rich or poor or in-between, whether flamboyant cross-dressers or “ordinary” people going about their daily affairs.

image from mochigrrl.blogspot.com

“Self-effacing” isn’t the first adjective that comes to mind when speaking of the fashion world, yet that is how Bill Cunningham comes across as the documentary’s crew follows him on his daily rounds, an impression that is only reinforced by the film’s direct interviews. Self-effacing not in the usual sense, which implies a degree of self-consciously holding back, but naturally so. His existence, in fact, strikes me as downright monastic.

At the beginning of the film, Cunningham lives alone in a tiny little closet of a room jammed full of file cabinets containing archival negatives and magazines, his only personal space a bookshelf or two and a small bed. (By the end of the film he has moved into somewhat larger digs because the building’s owner has decided to convert the old apartments into office space.) Every morning he gets up to ride his bicycle through the streets in search of people to photograph, a mode of transit which allows him the optimum mobility for navigating the city and the optimum flexibility to stop and shoot whomever happens to catch his eye. Unlike his subjects, Cunningham’s dress reflects the same monastic traits of simplicity and self-effacement as his living quarters and means of transportation: typically attired in casual pants and a smock-like blue jacket.

Like the true monk who has found his vocation, Cunningham exhibits unadulterated joy. His existence is focused solely on celebrating others with no concern for self. His delight in fashion comes from his delight in noting the ways that people express themselves artistically and aesthetically through their clothing; there is not the least trace of snobbishness in his attitude. With true wisdom, he says that for many of his subjects, clothing is their “armor to survive the reality of everyday life.” Near the end of the film, he states: “He who seeks beauty will find it.” That is his mission in life and quite obviously the source of his great joy.

Equally at home among socialites, gender-bending cross-dressers, and ordinary folk on the street, Cunningham looks to find beauty in every person; like the Biblical Creator who delights in creation, Cunningham seems to delight in every person he sees or meets, joyous to proclaim that “it is good.”

Early on, Cunningham displayed a strong sense of ethics. When the magazine he worked for in the 1960s took the photographs he had made of ordinary women wearing designer clothes as an occasion for mockery, he quit in indignation. Mockery was the exact opposite of his intent, which was fueled by fascination with the way that women in “ordinary,” middle-class circumstances would adapt the runway creations of designers to the needs of their own lives and the expression of their own individuality.

Towards the end of the film, the interviewer asks Cunningham about religion, and we discover that he attends Roman Catholic mass every Sunday. When asked whether religion is an important component of his life, Cunningham takes his time thinking it through before he finally says, “It’s a good guidance in my life. It’s something I need.”

Bill Cunningham’s life exemplifies a true sanctity and love for others, a joyous exuberance, and love for the world. Here’s to him!

Filed under: Saints Tagged: Bill Cunningham, fashion, films, photography

February 6, 2014

Thomas Merton’s “Night-Flowering Cactus”

Photos by German botanist, BotBin, from the Botanical Gardens in Berlin, via Wikimedia Commons

This post was partly inspired by one of my favorite blogs, StuffJeffReads, where Jeff focuses on poetry just as much as prose, often examining individual poems. Following last week’s post on Thomas Merton, I decided to focus on my favorite from his vast output of poetry, “Night-Flowering Cactus” (published in Merton’s poetry collection Emblems of a Season of Fury, c1963).

“Night-Flowering Cactus” is one of the most perfect blends of Christian spirituality and reverence for nature that I have ever encountered. Written in first person from the plant’s point of view, here is a truncated version:

I know my time, which is obscure, silent and brief

For I am present without warning one night only….

When I come I lift my sudden Eucharist

Out of the earth’s unfathomable joy

Clean and total I obey the world’s body

I am intricate and whole, not art but wrought passion

Excellent deep pleasure of essential waters

Holiness of form and mineral mirth:

I am the extreme purity of virginal thirst….

…. He who sees my purity

Dares not speak of it.

When I open once for all my impeccable bell

No one questions my silence:

The all-knowing bird of night flies out of my mouth.

Have you seen it? Then though my mirth has quickly ended

You live forever in its echo:

You will never be the same again.

The cactus’s prayer is its flower, which accords with Merton’s understanding that “For me to be a saint means to be myself. Therefore the problem of sanctity and salvation is in fact the problem of finding out who I am and of discovering my true self.” (Quote from banner on http://merton.org; I’m not sure of the original source.)

The cactus’s prayer is its flower, which accords with Merton’s understanding that “For me to be a saint means to be myself. Therefore the problem of sanctity and salvation is in fact the problem of finding out who I am and of discovering my true self.” (Quote from banner on http://merton.org; I’m not sure of the original source.)

Merton’s vocation as a Trappist monk, part of a silent order whose members are hidden away from the world, was the path that allowed him the scope to discover his true self. Like the Trappist monk, the night-flowering cactus blossoms in silence and obscurity, opening its deep white flower in the middle of the night. Like the night-flowering cactus, monks rise in the middle of the night to say prayers.

In liturgical churches—Roman Catholic, Anglican/Episcopal, Orthodox, Lutheran, and the like—the Eucharist, the celebration of Mass, marks the meeting place of heaven and earth, the ultimate symbol of The Holy. In the Roman Catholic tradition to which Merton belonged, when Christians partake of bread and wine, these earthly elements become “transubstantiated,” that is mystically transformed into the body and blood of Christ. While the Eucharist is not typically celebrated at night, there are certain special exceptions, such as Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve or Holy Saturday (the night before Easter), and the first stanza of the poem makes it clear that the night-flowering cactus blooms rarely: “I am present without warning one night only.” In searching for pictures on Wikimedia Commons, I discovered that it is also called in English the “Easter Lily Cactus.” (The botanical name is Echinopsis eyriesii.)

The literal meaning of “Eucharist” from the Greek is “thanksgiving,” and in this sense as well Merton’s Cactus offers its flower as thanks, gratitude, and praise. Anyone who has ever watched a seedling come up from the earth, gradually unfolding itself until it lifts its two leaves to the sky, will recognize the similarity to the actions of the celebrating priest who beginning from a bowed position of prayerful adoration then takes up the Host or Bread (white, like the Cactus’s blossom) and raises it to the heavens.

This stanza of the poem is the most moving to me, expressing Merton’s sense of the holiness of the earth, the “unfathomable joy” that nature in general and the soil in particular possess, the soil which makes possible all life through its “mineral mirth.” Like all nature, the Cactus is “not art but wrought passion”; like all plants, it is wrought from the “deep pleasure of essential waters” into “holiness of form and mineral mirth.” The flower’s essence is to rejoice, to model for us what holiness on earth might look like.

The last stanzas return to the theme of silence, and yet there is a tension between the plant’s silence and the poet’s silent witness, for ultimately the act of poetry has paradoxically managed to express that of which one “dares not speak.” A fitting conundrum, emblematic of Merton’s life.

Filed under: Books, Nature, Poetry, Spirituality Tagged: ecostory, Night-Flowering Cactus, Thomas Merton

January 30, 2014

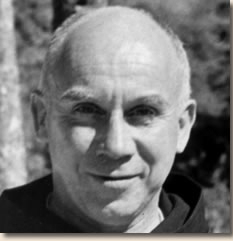

Happy Birthday, Thomas Merton

My favorite writer on spirituality, Thomas Merton was born January 31, 1915 “under the sign of the Water Bearer, in a year of great war, and down in the shadow of some French mountains on the borders of Spain,” as he put it at the beginning of The Seven Storey Mountain, the autobiography that detailed his life’s journey up to age 27 when he entered a Trappist monastery. An autobiography that plunged him into fame just as he retired from the world to one of the more austere Roman Catholic orders and had taken a vow of silence.

photo from http://www.monks.org/thomasmerton.html

I first encountered Merton’s writings when I was 27 and in graduate school. Every year just before Christmas, the campus bookstore had a big book sale, and faculty and graduate students got first dibs the night before it opened to undergrads and the general public. In those pre-Amazon days, it was quite the event. We graduate students eagerly looked forward to the invitations that would appear in our mailboxes, entitling us to gorge on books at a reduced price.

I don’t remember what exactly drew me to Merton’s autobiography. Perhaps I was vaguely aware of the name, and in any case I had a long-standing fascination with monasticism. In college I heard Samuel Barber’s Hermit Songs for the first time and was immediately taken with both the music and the words, monastic marginalia adapted by poet W.H. Auden. Barber’s setting of the last poem, “Ah, to be all alone, in a little cell, with nobody near me,” is particularly haunting, and his setting of an unknown monk’s ode to his cat, “Panga, white Panga, how happy we are, alone together, scholar and cat,” absolutely delightful, with an accompaniment that manages to be wholly musical while sounding quite like a cat pattering on the piano keys.

In any event, I was totally captivated by The Seven Storey Mountain and quickly moved on to devour Merton’s other writings. In particular, I was struck by his essay “Learning to Live,” which articulated many of my own concerns and answered them with his call to complete authenticity in every area of one’s life. (It was published in the collection Love and Living, one of the many posthumous collections of essays and other writings edited by his longtime literary agent, Naomi Burton Stone, and Brother Patrick Hart, who served as Merton’s last secretary.)

Like Tolkien, Merton was a Roman Catholic in a Protestant culture, something which must have given each an outsider’s perspective. Like Tolkien, too, Merton’s work reveals great reverence and respect for the natural world, which figures most prominently in his poetry. Merton’s passion for social justice and personal integrity became my guiding principles (not that I can claim to live up to such a model), and his diaries and other autobiographical writings show the struggles all of us experience as human beings trying and failing to lead good lives. They also show specific difficulties of the monastic life such as the struggles Merton experienced in balancing obedience to his superiors with the sometimes conflicting demands of his conscience when he felt obliged to speak out against racism and war. At a time when most religious persons regarded those outside their faith with suspicion or worse, Merton corresponded with Buddhists, Jews, Protestants, and Muslims, eagerly exchanging ideas and taking away much from their traditions that he felt could enrich his own religious practice.

Merton was also, first and foremost, a writer, and I can imagine no better patron saint.

Filed under: Saints, Spirituality Tagged: Thomas Merton

January 22, 2014

Cats and Dragons (Here there be Dragons; 3rd in an occasional series)

I generally try to avoid controversial topics, but here I boldly venture the opinion that those who love dragons are predisposed to also love cats.

My Dragon Cat by artist Amelie Hutt Smirtouille from Digital Art Gallery Online

Cats, like dragons, are predators. They may not breathe fire (though they are fond of warmth), but cats have often been accused of being selfish and standoffish. I daresay the same accusations have often been lobbed at dragons as well.

Why then are some of us so attracted to these predatory creatures?

To begin with, they are quite pleasing to look at. Both dragons and cats have graceful, sinuous bodies and long, equally sinuous tails. (“Sinuous” is one of my favorite words.) Both seem to grin, rather like Alice’s crocodile, a grin of deep and somewhat smug self-satisfaction that is nevertheless quite attractive.

In a previous post, I discussed the mysterious attraction that predatory animals hold for many of us: the way that raptors, owls, wolves, and big cats, among others, inspire us with feelings of wonder and awe. The love I hold for dragons and cats is a somewhat more domesticated version of this, and the feelings they incite are a safer, more comfortable and cozy sentiment that is removed from the dangers of the true wild. The house cat, a domesticated version of the wild’s tigers and lions, pleases cat lovers in part because its presence combines the pleasures of domesticity with the vicarious excitement of wild things in the same way that lovers of mystery enjoy curling up by the fireside with the latest thriller or a classically gruesome tale by Poe (often with a cat curled up on one’s lap). In the same way, dragons offer a similar sort of vicarious thrill as we read or view their adventures from the comfortable safety of our favorite couch or reading nook.

So, fellow dragons lovers, it’s time to weigh in. Are you cat people or fonder of dogs? I’m curious to know!

Filed under: Animals, Dragons & other fantastic beasts, Nature Tagged: cats, dragons

January 16, 2014

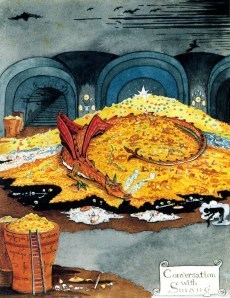

Here there be Dragons: Smaug (2nd in an occasional series)

As a follow-up to last week’s post on J.R.R. Tolkien, I thought I’d pen a few thoughts on visual images of Smaug, the dragon in Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

First we have Tolkien’s own illustration of the beast. Despite Tolkien’s literary portrayal of Smaug as an evil creature, the drawing is a delight to the eye. The dragon’s body is a graceful curve, ending in a fanciful fleur-de-lys tail, Smaug’s bright orange scales a pleasing and complementary contrast to the bright gold of his hoard. Like Alice’s Crocodile, Smaug’s claws are neatly spread, and their greenish cast makes them stand out against the background of gold. Crocodile like, too, is Smaug’s expression, not quite a grin, but the slight upward tilt suggests a degree of smugness and satisfaction with his accumulated (and ill gotten) wealth.

First we have Tolkien’s own illustration of the beast. Despite Tolkien’s literary portrayal of Smaug as an evil creature, the drawing is a delight to the eye. The dragon’s body is a graceful curve, ending in a fanciful fleur-de-lys tail, Smaug’s bright orange scales a pleasing and complementary contrast to the bright gold of his hoard. Like Alice’s Crocodile, Smaug’s claws are neatly spread, and their greenish cast makes them stand out against the background of gold. Crocodile like, too, is Smaug’s expression, not quite a grin, but the slight upward tilt suggests a degree of smugness and satisfaction with his accumulated (and ill gotten) wealth.

Tolkien drew another image in black and white, a stripped down version that again emphasizes the dragon’s pleasingly graceful curves and striking fleur-de-lys tail, while offering a better view of Smaug’s spectacular wings. This graceful image appears in my paperback edition of The Hobbit (Houghton Mifflin, corrected & revised text of 1978) on the two half-title pages.

Tolkien drew another image in black and white, a stripped down version that again emphasizes the dragon’s pleasingly graceful curves and striking fleur-de-lys tail, while offering a better view of Smaug’s spectacular wings. This graceful image appears in my paperback edition of The Hobbit (Houghton Mifflin, corrected & revised text of 1978) on the two half-title pages.

Peter Jackson’s second installment of The Hobbit gave us a marvelous Smaug. While not modeled precisely on the color drawing of Tolkien, Jackson’s Smaug remains true to its spirit. The closeup image of the dragon’s eye that ended Part 1 was a masterful stroke, and the sequel doesn’t disappoint. The film’s dragon is both graceful and menacing, its movements a sinuous ballet, the voice (actor Benedict Cumberbatch) precisely what I would expect, deep and Vadarlike, cultured and smugly amused by the puny hobbit. Smaug’s face, with the cat-slit eyes and catlike grin of the mouth, shows us an antagonist both elegant and cunning, attractive despite his evil intent. (Not something I would ever say of a human villain, but I just love dragons!)

The trailer below gives the most footage of Smaug that I could find–which is still only a few seconds right at the very end. Understandably the film makers wanted to give away only the barest teaser of one of the movie’s very best features.

And here’s a link to a fun and fascinating interview with the voice of Smaug, actor Benedict Cumberbatch (otherwise known as Sherlock Holmes—amusingly enough, his Watson, Martin Freeman, plays the young Bilbo). Lots of great details on how he went about playing Smaug.

Filed under: Books, Dragons & other fantastic beasts Tagged: dragons, Smaug, The Hobbit, Tolkien

January 9, 2014

J.R.R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born January 3, 1892, and this is a rather belated birthday tribute, occasioned by a recent viewing of the new Peter Jackson movie (The Hobbit, part 2).

I first discovered Tolkien in high school. It was the ’70s, the height of the Tolkien craze, and all the older kids that I admired were heavily into this master of fantasy literature.

I first discovered Tolkien in high school. It was the ’70s, the height of the Tolkien craze, and all the older kids that I admired were heavily into this master of fantasy literature.

I bought The Lord of the Rings books one by one, in what I think were the original paperback versions, and I can still remember the anguish with which I finished part 2, “The Two Towers,” where I was left hanging as the dread spider Sheelob nabbed Frodo, and Sam took off with the sword and the Ring.

Fortunately, the local bookstore (a B. Dalton’s) had “The Return of the King” in stock, and my nerves were saved. I became another Tolkien fan, and have reread The Lord of the Rings more times than I can count. It never fails to inspire and move me.

I didn’t read The Hobbit until much later, and it took me several years to accept it on its own terms, as more of a children’s book, though I am happy to say that I finally came round to liking it for its own sake. Still, The Lord of the Rings will always be my favorite of the two. Back in the day, I eagerly bought The Silmarillion when it came out, and picked up other odds and ends of Tolkieniana from sale tables and used book stores over the years, so that we now own a Tolkien atlas, an oversized book of Tolkien illustrations, a Tolkien Bestiary, and his lovely Father Christmas tale, complete with the charming illustrations. Tolkien’s drawings were every bit as fine as his stories, delicately drafted creations that have quite an elvish flavor about them.

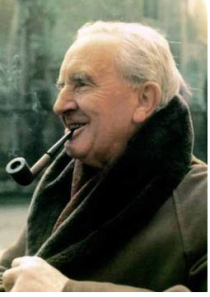

I also love photographs of Tolkien himself. A hobbitsy looking man if there ever was one, with all the doughty, understated qualities of a hobbit’s character to boot. His biography makes for fascinating reading.

I also love photographs of Tolkien himself. A hobbitsy looking man if there ever was one, with all the doughty, understated qualities of a hobbit’s character to boot. His biography makes for fascinating reading.

One aspect of Tolkien’s work that I find especially sympathetic is his attitude of reverence and respect for the wonder and beauties of Nature—an attitude that never runs to sentimentality, and is fully aware of the dangers that Nature holds as well (think of Old Man Willow!). The Ents in particular are my absolute favorite of his creations. Treebeard is a marvel, and it tickles my fancy to think that Tolkien modeled Treebeard’s booming delivery on his friend C.S. Lewis, another famous Oxford don who was part of Tolkien’s circle.

Every time that I read about some horrible environmental degradation or see a beautiful, healthy tree wantonly chopped down in a neighborhood yard, I have a fierce longing to evoke the vengeance of the Ents upon the offender, wishing that I could call upon the mighty shepherds and defenders of trees to mow down these destroyers of beauty as they mowed down Saruman’s nasty little fiefdom. Like the evil wizard, too many people these days possess “minds made of metal and wheels” as Tolkien so aptly put it—completely blind to the beauties of the natural world.

The religious aspects of The Lord of the Rings are woven into the tale with equal subtlety. The moral growth of Frodo and Sam that leads to their sacrificial journey to Mordor, the wisdom of Gandolf, Galadriel, and Aragorn, and the beauteous vision of Tolkien’s Elves all lend themselves to our moral and religious stories, no matter what our faith. The Lord of the Rings is truly a timeless and universal tale, and Tolkien a towering literary saint.

Filed under: Books, Nature, Saints Tagged: Ents, The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien

December 28, 2013

Merry Christmas & Happy New Year

Saints and Trees will return in two weeks.

The Beeston Christmas Tree, photo by mattbuck via Wikimedia Commons

New Year’s in Village. Photo by Jon Sullivan via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Filed under: Feasts/Seasons

December 19, 2013

Christmas Bells

I’ve always loved the sound of bells and I love the Christmas carols that feature them. The first that comes to mind is the setting of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” which is worth quoting in full, as its message of peace remains more relevant than ever:

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet the words repeat

Of peace on earth, good will to men.

I thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along the unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good will to men.

And in despair I bowed my head:

“There is no peace on earth,” I said,

“For hate is strong and mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good will to men.”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth he sleep;

The wrong shall fail, the right prevail,

With peace on earth, good will to men.”

Till, ringing singing, on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime, a chant sublime,

Of peace on earth, good will to men.

And then there’s Edgar Allan Poe’s superb “Hear the sledges with their bells, silver bells.” Even though the poem ends with funeral bells (it’s Poe, after all!), the first stanza evokes quite a festive mood. The poem also introduced me to a most marvelous bell word: “tinntinnabulation.” Here’s that first stanza:

Hear the sledges with the bells -

Silver bells!

What a world of merriment their melody foretells!

How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,

In the icy air of night!

While the stars that oversprinkle

All the heavens, seem to twinkle

With a crystalline delight;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells -

From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.

Another favorite of mine is the Ukranian Bell Carol. When I first heard it as a child it seemed so mysterious, so different from the other carols I knew. According to Wikipedia, the melody, composed by Mykola Leontovych , is based on a Ukranian folk chant, which partly accounts for the carol’s mysterious, evocative tone.

Here’s a version I found on youtube. I wish they had given the name of the children’s choir. It’s a lovely rendition:

What are some of your favorite holiday songs or poems featuring bells? It doesn’t have to be Christmas; I’m curious about other traditions, as well.

Filed under: Feasts/Seasons, Music, Poetry Tagged: Christmas carols, Edgar Allan Poe, Ukranian Bell Carol

December 12, 2013

Church Bells

A few weeks ago, I set out for my daily walk, my destination the local library. My husband and I were both suffering from colds, so we’d slept in, and it was 11:30 by the time I left the house, carrying a backpack of soon-to-be-overdue books.

Church tower of Cathedral St. Anastasia, Zadar, Croatia. Photo by Bohringer Friedrich via Wikimedia Commons.

It was an unseasonally warm Sunday, just above 60 degrees Fahrenheit, a beautiful late-autumn day with the sun shining brightly through the trees, transforming the remaining leaves into stained-glass windows colored in flame. Rounding a corner, I faced into the sun, and as it shone out, the bells from a nearby church began to peal.

I’d heard the bells before. I tend to take my walks around midday, and had often heard the church carillon ring out familiar hymns. It was always a pleasant accompaniment. But this was quite different, no tunes, just a wild, joyous cry, bells from high to low, deep-voiced through treble, pouring out in a jubilee that reminded me of my recording of the Coronation Scene in Boris Godunov. The bells and the sun created a moment of pure wonder and beauty.

On my way home from the library, on the very same block, I heard the bells again. But this time it was the familiar Big Ben chime, followed by a singularly appropriate hymn, “For the Beauty of the Earth” (one of my favorites). From the sublime moment earlier in the walk to the comforting and familiar as I wended my way home, I felt grateful, blessed by the bells.

Here’s the coronation scene from Boris, the version with the best bells of those I could find on youtube (couldn’t find the scene from the recording I own, which features Boris Christoff in the title role, but the bells on the recording below are also quite spectacular):

Filed under: Feasts/Seasons, Music, Spirituality Tagged: bells, Boris Godunov, church bells, Mussorgsky