Mark Caney's Blog, page 5

February 21, 2020

The gleam of intelligence…

A review of Dolphin Way on Amazon, by Derron T

I am a prolific reader but nonetheless I finished this book in 4 evenings,

Mark Caney has an easy writing style and bought the characters to life, having had eye to eye contact with wild Dolphins I cannot deny the gleam of intelligence these beautiful creatures possess.

Can’t wait for the 2nd book.

February 18, 2020

A new understanding of dolphin and whale evolution

Scientists could soon better investigate the feeding behaviors of extinct dolphin and whale species. A third year student at Japan’s Nagoya University has found that the range of motion offered by the joint between the head and neck in modern-day cetaceans, a group of marine mammals that also includes porpoises, accurately reflects how they feed. The authors of the study, published in the Journal of Anatomy, suggest this method could help overcome current limitations in extrapolating the feeding behaviors of extinct cetaceans.

Taro Okamura of Nagoya University and Shin-ichi Fujiwara of the Nagoya University Museum examined the skulls and cervical skeletons of 56 cetaceans that are still in existence, representing 30 different species. They assessed the range of motion of the ‘atlanto-occipital joint’ in each skeleton, a joint that forms between the base of the skull and the first cervical vertebra. They then categorized each cetacean according to their well-studied feeding behaviors, including how they approach their prey, move it within their oral cavities, and swallow it.

“We found that the range of neck-head flexibility strongly reflects the difference of feeding strategies among whales and dolphins,” says Okamura. “This index can be easily applied to reconstruct the feeding strategies of extinct whales and dolphins,” he adds.

Cetaceans are known for their diverse behaviors, physiologies, ecologies and diets. Some cetaceans feed on organisms in the open water, while others feed on those found near the ocean floor. Some whales are ram feeders, widely opening their mouths to gather zooplankton and other actively swimming organisms into their mouths while moving forward. Other whales, like the sperm whale, suction their prey into their oral cavities. The orca whale and some dolphins bite the fish they catch into smaller segments, a process that may require head movement. Other dolphins swallow their prey whole.

Until now, scientists have used the structures of teeth, throat bones and lower jaws in cetacean fossils to develop an idea of what their feeding behaviors might have looked like. But these individual features can’t accurately predict the behaviors of extinct cetaceans. For example, the teeth of some suction feeders, like those of the sperm whale, aren’t suggestive of this kind of feeding. Okamura and Fujiwara propose that using a combination of features, which include the range of motion of the atlanto-occipital joint, could help to develop more accurate descriptions of extinct cetacean feeding behaviors.

In prehistoric times, many different types of cetaceans existed, including ones with walrus-like tusks, extremely long snouts, and an ancient sperm whale with huge predatory teeth. The ancient baleen whale had teeth, whereas modern-day baleen whales have ‘baleen,’ or fringed plates, in their place. This has created much interest in how baleen whale feeding, for example, has evolved from catching prey with teeth to filtering it with baleen.

The two researchers next plan to determine the atlanto-occipital joint range of motion in some of these cetacean fossils to attempt to develop reconstructions of how they used to feed. Answering these questions could help reveal the evolutionary process of the diverse feeding behaviors among cetaceans.

Source: Science Daily

February 16, 2020

Weird ‘dolphin-like creature with no eyes or fins washes up on Mexican beach

A mysterious dolphin-like creature with no eyes or fins has reportedly washed up on a Mexican beach.

Fishermen at the popular surfers’ beach of Destiladeras told local media it could have come from deep in the Pacific Ocean.

The discovery of the stranded beast – with a strange tail similar to an eel’s – took place in Punta Mita, in the western Mexican state of Jalisco which is on the Pacific coast, reports Tribuna De La Bahia.

With its dolphin-like head and sharp teeth, but lacking any flippers, it apparently startled many people.

Tribuna said that the “strange creature” was found dead and “caused a furore on social media” and among residents.

Full story: The Sun

“Dolphins in this novel are finally depicted as three-dimensional beings”

A recent review of Dolphin Way on Amazon by Anjoulie (the original review was in German).

When

you are an adult looking for books about dolphins that do not belong to

non-fiction or to the esoteric industry, you often encounter the following

problem: Everything is written for children or young people. Mostly from the

point of view of people who first encounter dolphins on x sides and then speak

about the animals from their perspective.

The author of this book does it differently and I could hug him for it.

“Dolphin way” is an animal novel from the perspective of (humanized)

animals. It’s about the bottlenose dolphin “Touches the sky”

(“Touches die Himmel”), but almost always called “Sky” in

the book, whose life is getting more and more difficult because the schools of

fish are increasingly missing. Another shoal of dolphins appears, who call

themselves the “Guardians”, who no longer adhere to the old teachings

of the dolphins. This includes, among other things, the absolute prohibition of

violence among fellow species. Their leader named “Storm after

Darkness” seems to be targeting “Sky”. But why?

What at first sounds like nice, shallow fantasy for under ten year olds turns

out to be a very exciting story on the first pages, which I would really only put

in the hand of young people and adults.

“Touches the Sky” has to watch in the first chapter how a friend is

seriously wounded on the beach and dies painfully. She’s not the only dolphin

to die in this book, I can tell you that much.

I particularly liked that dolphins in this novel are finally depicted as

three-dimensional beings and not as chronically happy cuddly toys of the ocean.

That makes the novel very exciting and I was really disappointed when it was

over. I justify the missing star with the abrupt end that cries out for a

sequel. The author has left so much open that it is too much even for the start

of a multi-part game, at least that’s my opinion.

For all who are unsure whether their English skills are sufficient: Those who

had a stable 3 up to the 10th grade should come.

August 11, 2019

Dolphin spotted juggling with jellyfish

Two friends have captured footage of a dolphin flipping jellyfish with its nose, in the harbour at Sønderborg, in the south of Denmark.

[image error]

See the video on the BBC site:

July 24, 2019

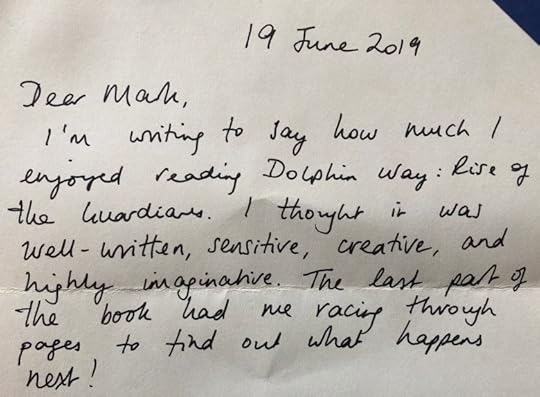

Reader praises Dolphin Way

We just received this lovely letter from a recent reader of Dolphin Way – glad to hear that he enjoyed the book so much!

New video trailer for Dolphin Way

Check out this new 90-second video that explains what Dolphin Way is about

May 26, 2019

Dolphin study reveals the genes essential for species’ survival

UNSW scientists have added to the growing body of research into genetic markers that are important for animal conservation.

Certain types of immune genes may be particularly important for the survival of dolphins, a new study by an international team of researchers that investigated genetic diversity of dolphin populations reveals.

Knowing which genes are essential for helping dolphin populations survive has important implication for conservation: it is often difficult to monitor changes in population sizes of wild animal populations, especially long-lived dolphins, who spend most of their time underwater. This also makes it hard to detect whether these populations are threatened—so identifying genes that are essential for survival could offer an indicator for potential threats to the viability of populations.

Knowing which genes are essential for helping dolphin populations survive has important implication for conservation: it is often difficult to monitor changes in population sizes of wild animal populations, especially long-lived dolphins, who spend most of their time under water. This also makes it hard to detect whether these populations are threatened—so identifying genes that are essential for survival could offer an indicator for potential threats to the viability of populations.

“Genetic diversity is crucial for animals to adapt to a changing environment—for example, diverse genes can help populations defend against diseases and tolerate climate change—but not all genetic diversity is equally important,” says lead author Dr. Oliver Manlik, who is an Assistant Professor at the United Arab Emirates University and conjoint faculty member of UNSW Science.

Until recently, most studies that assessed genetic diversity in wild animals used “adaptively neutral” genetic markers that don’t offer any clues as to whether animals can adapt to a changing environment. Adaptively neutral genetic markers are gene variants that usually do not have any particular function, and are neither beneficial nor harmful to individuals or populations. Such genetic variants are, therefore, not so important for adaptation or survival.

“In order to identify genetic variants that are necessary for animals to adapt and to survive, it is important to focus on genes that are linked to ecologically important traits,” Dr. Manlik says.

“One such group of genes are the immune genes of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which play a critical role in recognizing pathogens and starting an immune defense.”

In their new study, published in the international journal Ecology and Evolution, the scientists compared “adaptively neutral” genetic diversity and genetic diversity of MHC genes in two bottlenose dolphin populations in Western Australia. One of the two dolphin populations, in Shark Bay, was previously assessed to be stable. In contrast, the other, much smaller population near Bunbury was forecast to decline, unless it is supported by immigrants from other populations nearby. This was shown in two previous studies, which were also led by Dr. Manlik.

“In the study published today, we found that the large, stable population in Shark Bay exhibited much greater MHC diversity than the smaller, less stable population,” Dr. Manlik says.

“On the other hand, there was almost no difference between the two populations with respect to neutral genetic diversity.”

Professor Michael Krützen at the University of Zurich and co-author of the study says the Shark Bay dolphins, which carry greater immunogenetic diversity than their counterparts off Bunbury, are likely more robust to natural or human-induced changes to the coastal ecosystem.

“In other words, having greater MHC diversity may offer extra protection to these dolphins, but certainly does not make them invincible to the many threats they face.”

The findings of the study also suggest that MHC diversity could be a useful indicator of population health of these dolphins and possibly other vertebrates who also have MHC genes.

Full story: phys org

May 4, 2019

‘Russian spy’ whale has defected to Norway, locals claim

A beluga whale that may – or may not – have been trained to spy for Russiaappears to have defected to Norway, refusing to stray more than a few miles from the small northern harbour where it was found on Monday and entertaining locals with tricks.

“He’s so comfortable with people that when you call him he comes right up to you,” Linn Sæther, a resident of Tufjord on the Arctic island of Rolvsøya, told Norwegian public broadcaster NRK, which has launched a poll to find a name for the mammal.

Sæther said locals had been able to pet the whale, which was found at sea by Norwegian fishermen on Sunday wearing a harness fitted with a mount – apparently for a camera or weapon – and stamped with the words: “Equipment St Petersburg.”

[image error] Linn Sæther poses for a selfie with the beluga whale in Tufjord, Norway.

The beluga performs twirls and leaps and happily retrieves plastic rings, she said, before swimming up to the dockside with its mouth open, as if looking for a fish in reward. “It is a fantastic experience, but also a tragedy,” she said.

“It’s clearly used to being given tasks and having something to do,” Sæther said. “It reacts when you call it or splash your hands in the water. You can see it’s been trained to fetch and bring back whatever is thrown for it.”

Tor Arild Guleng told the broadcaster the whale had followed his boat on a one-hour voyage from Rolvsøya back to Hammerfest. “It followed me, like an obedient dog without a lead,” Guleng said. “No wild animal seeks you out, sticks its head up and allow you to stroke its nose.”

Initial speculation was that the whale had escaped from a Russian military facility. Audun Rikardsen of Tromsø’s Arctic University of Norway said the Russian navy in Murmansk, the headquarters for Russia’s northern fleet, could be involved.

The Russian defence ministry has denied running a sea mammal special operations programme and Norway’s special police security agency (PST), which is examining the harness, has not yet concluded its investigation into where the whale came from.

Full story: The Guardian

May 1, 2019

Study helps us understand evolution of marine mammal communication

The Araguaian river dolphin was just discovered and described to science in 2014, so it’s no surprise that there’s a lot we don’t know about the cetacean native to the Araguaia and Tocatins rivers in Brazil.

Until recently it was believed that the solitary nature of Araguaian dolphins meant that they wouldn’t have much use for communication. But scientists have now documented hundreds of sounds made by the dolphins — and they say that these vocalizations could help us better understand the evolution of underwater communication among marine mammals.

Though the waters of the Araguaia and Tocatins rivers are relatively clear, Araguaian dolphins, known locally as botos, are difficult to even locate, let alone study in the wild. The animals are quite skittish and usually flee when in the presence of humans.

But Gabriel Melo-Santos, a biologist from the University of St Andrews in Scotland, discovered that many of the dolphins frequent a fish market in the Brazilian town of Mocajuba, where shoppers typically feed the dolphins. Melo-Santos led a team of researchers that took advantage of the clear river water and the dolphins’ regular visits to get an up-close look at the animals’ interactions and behavior. The team detailed their findings in a study published in the journal PeerJ last month (the study was first published in PeerJ Preprints last year).

Using underwater cameras and microphones to record interactions between the dolphins visiting Mocajuba, Melo-Santos and team recorded 20 hours of vocalizations, which they classified into 13 different types of “tonal sounds” and 66 types of “pulsed calls.” In total, they identified 237 distinct types of calls.

The researchers say their findings show that Araguaian dolphins’ acoustic repertoire is anything but simple. “We found that they do interact socially and are making more sounds than previously thought,” Laura May Collado, a biologist at the University of Vermont and co-author of the paper, said in a statement. “Their vocal repertoire is very diverse.”

The most common sounds the dolphins made were “short two-component calls,” the researchers report in the study. About 35 percent of these calls were made by calves while reuniting with their mothers, which suggests that the calls are an important component of mother-calf communication. According to May Collado, “marine dolphins like the bottlenose use signature whistles for contact, and here we have a different sound used by river dolphins for the same purpose.”

The researchers theorize that the botos’ habitat is what caused them to evolve towards calls with shorter durations, since the echoes of longer calls would be subject to more interference in rivers than they would in oceans. That complex habitat might also explain why the acoustic characteristics of the river dolphin’s calls is somewhere between the low-frequency calls used by baleen whales to communicate over long distances and the high-frequency calls used by marine dolphins for short-distance communication. “There are a lot of obstacles like flooded forests and vegetation in their habitat, so this signal could have evolved to avoid echoes from vegetation and improve the communication range of mothers and their calves,” May Collado said.

The river dolphins made longer calls and whistles, as well, but these sounds were much rarer and the researchers have yet to deduce the dolphins’ uses for them. However, Melo-Santos and co-authors write in the study that botos use these longer whistles in much different social contexts and for what appears to be quite different purposes than their ocean-dwelling cousins: “keeping distance between each other, rather than promoting social interactions as in marine dolphins.”

The researchers say they next plan to study whether or not other populations of Araguaian river dolphins that have had less contact with humans employ the same diversity of calls, and then compare the results with the dolphin’s closest relatives. Two species, the Bolivian river dolphin and the Amazon river dolphin, are closely related to Araguaian dolphins, yet their vocal patterns are substantially different. Amazon dolphins in Ecuador, for instance, which May Collado studied in 2005, are not nearly as talkative.

Full story: Mongabay