Luanne Rice's Blog, page 6

February 20, 2017

Vigilance

Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer in "Gaslight." MGM

There is a feeling of holding on, of getting through, of balancing on a precipice. When you're lied to by someone in power, it's the same as being gaslighted in an abusive relationship. You're being told one thing, but you know it's wrong, you know it's false. To mix movie metaphors, it's also the Wizard of Oz telling us "pay no attention to that man behind the curtain." But we have to pay attention. And, frankly, the wizard was too genial and well-meaning to be an apt comparison here. We're dealing with a bully who who not only lies but is a stranger to caring about others.

A spirit of hate, intolerance, denial of climate change, erosion of rights, disdain and disrespect toward women has emerged. I have nieces and many young women I love. They're devastated, and so am I, to think that someone who spoke the way he did about women could have been elected (not really elected.) To have our choices and health care threatened, to have the planet--on which our young people will live long after we're gone--endangered and ruined, is a heartbreak.

Collective trauma. Everything is a potential trigger. Hate speech, purposeful confusion, being told that what you see, what you hear, is untrue, that a different reality is valid and being counted as the real reality, all trigger a feeling of powerlessness.

The beauty is, so many of us have found a voice. Demonstrations and marches and constant reminders in my twitter feed that people are on it. We are more than paying attention. We are promising to steward the earth, to protect the most vulnerable, to remember that we're a country of immigrants, that we have a free press. We are doing this.

women's march on washington photo: suchat pederson, usa today

Our skepticism and refusal to be in denial will serve us well. Keep recognizing what's wrong, what's a lie, and stay vigilant like this:

[image error]

Ingrid Bergman in "Gaslight." MGM

Vigilance will keep us strong. Recognizing that we're being gaslighted, calling it what it is, creates awareness, and awareness is power. Remain aware. Pull together. Don't lose hope or heart. It's the best we can do right now. And it's a lot.

We'll turn this around. Liars get caught, tripped up in their own lies. Watch and wait and, more than anything, keep speaking out. Your voice matters. You've called your congresspeople to protest unacceptable cabinet picks, you've marched to show strength in great numbers, you're saying that bullying isn't okay, it's far from okay. You're refusing to accept lies. Stay connected with each other and remember: in the movie Gaslight, after all, goodness prevailed, the gaslighter was called out for the liar and bully he was, and this happened:

[image error]

Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer in "Gaslight." MGM

The tables were turned. Believe in the power of your voice. That's how we bring about change. That's what we're doing. Take heart, we have each other.

xxoo Luanne

January 28, 2017

New York Times bestselling Author Luanne Rice On The Power Of Sisterhood

Photo credit: Kristina Loggia

The paperback of THE SECRET LANGUAGE OF SISTERS comes out on Tuesday, January 31. Jeryl Brunner interviewed me for Forbes, and I talk about the book, writing, and sisters. Here is the link. Jeryl is always so supportive and I love her stories on theater, the arts, books, and so many other topics. I first met her when she included me in her book MY CITY, MY NEW YORK.

January 18, 2017

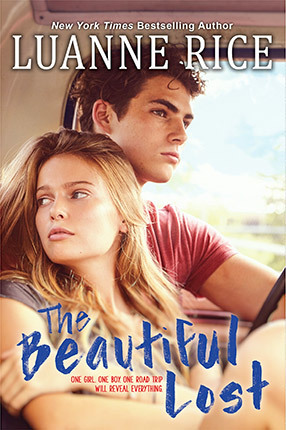

The Beautiful Lost

I'm thrilled to let you know The Beautiful Lost cover reveal is live on USA Today/Happy Ever After blog right now!

I've always loved hearing about mothers sharing my books with daughters, aunts with nieces, and now it’s the other way-round: Young readers are discovering me, introducing my work to their mothers, teachers, aunts, friends. It gives me more joy than anything. The Beautiful Lost, my second YA novel, comes out this summer. It tells the story of Maia, a girl struggling with depression who takes off on a road trip in search of her mother. Maia’s talisman, the object that gives her strength and contains the map to find her way, is, of course, a book.

And I'm really happy to tell the fans of my Hubbard's Point novels that there's a strong connection in The Beautiful Lost...

Pre-Order: Amazon

December 22, 2016

Winter Solstice

The winter solstice feels pure and eternal. The beach is so quiet, not another soul around. No voices, just the sound of the waves, the wind in the reeds. There are buffleheads and mergansers in the pond and off the point, and a lone osprey circles the bay. Is he a juvenile as one birder friend of mine suggests? Was she left behind when the others left on their migration months earlier?

Last week snow blanketed the beach, and a thin film of ice covered the boat basin, cracked and moving with the tide. The ice melts most days, reforming in late afternoon, when the temperature drops. On very cold days a layer of sea smoke forms past the big rock and breakwater. The cold, white mist is mesmerizing, and I watch it move in and out, closer to shore and out toward the middle of the Sound.

There will be a snowy owl, or maybe there won't. But owls are my favorite birds, and snowies are my favorite owls. They inhabit the arctic, and during years when prey is scarce, they fly south and grace these parts with their presence, seeking flat, tundra-like habitat--beaches, fields, airport runways. If you see one, protect its locaton. They are vulnerable, and too many people will disturb them. Owls are the most secret of birds.

The snow has melted for now, but I'm hoping for more.

ice on the boat basin

[image error]

the herb garden during the storm

bone-white driftwood

the lovely woods

waiting at home, after my walk...

December 13, 2016

Deconstructing Stigma: A Change in Thought Can Change a Life

My photo from Deconstructing Stigma: A Change in Thought Can Change a Life (credit: Patrick O'Connor)

I spent Friday at Boston's Logan Airport celebrating Deconstructing Stigma, a project developed by McLean Hospital. It's an amazing exhibit, intended to start a conversation about mental illness and the stigma that often surrounds it. The walkway between Terminals B and C is lined with photos of people affected, including me--I've dealt with depression since I was a teenager. Although the images are larger-than-life, the stories told are human-sized: intimate and personal.

Amy & Jason

The day was emotional for me. I loved meeting some of the other people in the exhibit. Their honesty and openness moved me greatly and made me feel part of a wonderful group. Sean, who had his first panic attack at 13, when his mother was dying of cancer; Carol, who during her freshman year of college in 1958 was told by the dean to take a semester off--because mental health was rarely discussed back then, it took decades for Carol to be properly diagnosed and learn that she had bipolar disorder; Nathanial, whose obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) began when he was in eighth grade. I stuck close to Amy--a really good friend. We met when her husband Jason and I were patients on Proctor 2 at McLean. Their photo is on the wall too, with Amy's quote "We're always looking out for each other."

Howie Mandel, Maurice Benard, and Darryl McDaniels, and other celebrities are featured in the exhibit. Darryl, a founding member of Run-DMC, spoke before the reception, powerfully telling of his struggles with depression, addiction, and suicidal thoughts. But what strikes me most about the stories is that, whether famous or not, we have so much in common. We've all been affected by mental illness, and are here to talk about it, to reach out to others and say there is help.

With Marylou Sudders

Marylou Sudders, Secretary of Massachusetts Department of Health and Human Services, introduced the event with such compassionate comments. She spoke of her own family, telling how her mother died young from complications related to psychiatric illness, and she welcomed us with the knowledge and understanding of how these issues affect us all.

I was over the moon to see my doctor and nurses from Proctor 2. From left: Paula Burley, Nina McCloskey, Erica Skorupski, me, Dr. Sherry Winternitz, and Christina Lee.

There were so many great moments, but one really stands out for me. I had requested that several people very important to me be invited, and I honestly didn't think they'd make it. They're so busy, they have many patients, would they even remember me? But they showed up, and I was over the moon to see them. These women took care of me the times I was hospitalized at McLean for depression. They listened for hours on end, they made sure I--and all the patients on Proctor 2, the trauma unit that does nothing less than save lives--were safe. They helped me get well. If you've read my books, you've seen characters of mine--nurses, doctors, healers--inspired by them, and sometimes with the same first names.

I am very thankful to Adriana Bobinchock, Director of Public Affairs and Communications at McLean, for inviting me to take part and being so incredibly encouraging and kind. Epic thanks also to Gerald Dawson for overseeing the photo shoot and doing so much to organize the event and bring everyone together. Patrick O'Connor is the photographer who took the beautiful pictures, and Steve Close is the creative director--both came to my house with Gerry, and not only did they do a great shoot, they made it so much fun.

I hope Adriana won't mind my sharing something I wrote in an email to her today, thanking her for everything and telling her my feelings about seeing the photos in the concourse: "travel is stressful but also a time for reflection--all that time in airports, and on the plane--and i've had more than one revelation on a long flight or heading to the car afterward. i think the exhibit is well-positioned to touch people at their most vulnerable, when they might be most ready to realize they need help, or to soothe their worries of being alone/different/isolated/broken." Those people are not alone--we are with them.

That is what it's all about: listening to each other, caring for each other, seeking help when you need it. Your story matters. It makes you who you are. Your experiences and emotions add up to a wonderful life, but sometimes there is pain along the way. It's better than okay to admit that--it's actually great. Tell your story. We want to listen. Actually, we need to.

Much love, Luanne

With Darryl McDaniels

December 2, 2016

Silver Bells Redux

Every year, on the first of December, Christmas trees arrive in New York City. The same families come year-after-year and set up their stands on the same street corners. There is one on Ninth Avenue in Chelsea that inspired me to write SILVER BELLS. I am always so happy to see the people again, to round the corner of West 22nd Street and smell the trees, to feel I've stepped into a grove of pines in the far-north.

Christmas trees and the last of this year's roses in Abingdon Square

Yesterday my dear friend and literary agent Andrea Cirillo and I walked from Chelsea to Soho. Along the way we passed other tree stands, and loved seeing this one in the West Village--Christmas trees juxtaposed with the year's last roses. We wound up at a favorite haunt--the always charming Balthazar--to meet my wonderful editor Aimee Friedman for a festive lunch.

We have lots to celebrate--starting with the paperback of THE SECRET LANGUAGE OF SISTERS coming out January 31, 2017. After lunch we headed a block north on Broadway to the enchanted offices of Scholastic for a meeting with some of the most extraordinary people I've ever worked with: David Levithan, Rachel Feld, Tracy van Straaten, and Jennifer Abbots. I feel so lucky that Scholastic will be publishing my second YA novel in June 2017. THE BEAUTIFUL LOST tells the story of Maia, a girl struggling with depression who takes off on a road trip in search of her mother. (It's very close to my own heart and experience, and I'll be writing much more about that here.)

With Aimee Friedman and Andrea Cirillo at Balthazar.

September 22, 2016

Fall

Fall begins today.

I am happy. My sister Maureen is sad. She feels melancholy when summer officially ends. I welcome the shorter days and cozier nights. She misses carefree sails, every evening after work, with her husband Olivier, out of Noank and back. I like apples. She makes apple pies. Maybe she will make one and feel happy. I hope so. I know I will, because she will give me a piece, and she makes the best pies in the world. I also hope she has many more sails before it's time to take the boat out of the water. But still; I respect her sadness even as I love the season. It's funny, how two people so close can feel completely different ways about the same thing.

My friend gave me a chrysanthemum.

from my friend

September 14, 2016

September

It is peaceful. The summer people have gone home. Kids have started school. I miss them, even though I love the quiet. I'm not talking about kids in my family but, rather, the children of summer, who play on the beach all through July and August, whose constant calls of glee as they tease the small waves of Long Island Sound drift up the hill to find me at my desk. Now I hear waves, wind in the trees, birds singing; but i miss the joyful beach sounds.

Still, there is plenty of joy. September skies are heart-cracking blue. The windows are open. A constant sea breeze blows through. It carries the first scents of fall. The leaves on the eighty year-old oak outside my kitchen window are still green, but there are clusters of acorns, and the green is darker, more subdued than it was last week. Soon they will turn golden. But not today.

I write at this desk. My cats keep me company, sleeping in old baskets that have been here so long, their woven slats have snagged bits of fur, silver and ebony, from cats who have long since left us. The baskets themselves have carried tomatoes and mint from my mother's garden, moonstones collected on the beach at dusk, pine cones to place on the mantle at Christmas.

This week I went sailing with my sister, brother-in-law, and niece. We left Noank on a day so sunny and warm it felt like the heart of summer, not the end of it, and we wound up in East Harbor. We swam and laughed, picnicked on produce from Whittle's Farm Stand, then swam some more. The heart tugs in September, perhaps more than any other time of year. There's an awareness that time may be short--next week weather could roll in, the temperature could drop, this might be our last good sail of the summer.

But the beauty of September is that we don't know. Every day is beautiful, and change is part of that. Fall is coming, and the air is spicy. I've found a warming bed for my oldest cat, and when she circles twice and lies down, the way she does, the heat of her body will be held in the mylar lining, and she will stay toasty all night. Soon there'll be no more corn at the farm stands, no more butter-and-sugar or silver queen. The last of the tomatoes, basil, green beans are here, but we don't know quite for how long. But I'm looking forward to apples, butternut squash, cider, pumpkins, shelves and shelves of yellow and russet chrysanthemums.

My sister said, as we were salt-crystaled from our swim, drying off in the sun on deck, "This is our last sail to East Harbor this year. The weather's going to change. I will get cold." I'm an optimist, but she's right: eventually the north wind will blow, we'll have a frost, we'll be wearing fleeces instead of bathing suits. But not today. So I could put my arm around her shoulder and say we'd be back next week, and the week after.

We turned for home, had a perfect sail, only one tack back to Noank. We took the dinghy from the mooring into the dock and hugged and said talk to you tomorrow, see you soon. And we would, and we would. I drove home to Hubbard's Point, to the small beach cottage my grandparents built, where the cats were waiting to be fed.

I fed them. The sound of the waves came through the window. The sun had set, the sky through the pine trees was fiery. My skin was still salty from the sail and swim, and I didn't want to wash it off. Not yet. I wanted to hold on to everythign about the day for as long as I could. I wanted to say thank you for it, I wanted to call it out, down to the beach, across the water.

It's no coincidence the name of the boat is Merci. No, I'm sure that's no coincidence at all.

Merci

Maureen and Olivier aboard Merci

Amelia and her dad Oliver.

Two sisters.

September beach day.

September 10, 2016

Woman in a Yellow Dress

The Wind by RHADS (used with permission)

In some ways it’s hard to call up the emotions of that day. In others they are as alive as ever. I wrote this piece in September 2001, a week after the towers collapsed.

Woman in a Yellow Dress

by Luanne Rice

Last Wednesday, a week and a day after the World Trade towers fell, I was crossing Park Avenue South at twilight when I saw a woman in a yellow dress climb out the window of her fifth floor apartment.

On my way west from Gramercy Park, I stopped in the middle of the street. Eight days earlier the world had changed, and I was moving slowly. As the woman inched along the ledge, clinging to the sash, it took me a moment to realize what I was seeing. I don’t have a cell phone, and I couldn’t find a quarter, so I ran into the corner bodega--directly below her window.

The counterman dialed 911.

Time did a funny thing. It sped up and stopped, both at the same time. A buzz went up—all around—as a crowd began to gather outside. The store sold fresh flowers and smelled like a garden. Sirens—a constant sound all week—grew louder, came closer and stopped outside. The police cordoned off the street. More people crowded against the police tape.

I stayed inside the bodega. Five floors up, the woman was directly above me. Amid the noise, the sights and smells, everything seemed still and quiet. My own heart pounding, I imagined hers: beating hard, fear, despair. You’re alive, I thought of myself, of her.

All week the city had been burning. The air below 14th st. was smoke and ash. The wall next to Famous Ray's Pizza in the Village was still covered with posters put there by family members--photos and descriptions of fathers and mothers and daughters and sons and friends and everyone who'd been in the towers and were missing since that day. They were still missing. Sirens sounded all day long. I lived in the city. I was at Charlotte in midtown with my editors when the first plane hit. We hurried home, and when the buildings fell I felt the ground shake. Father Mychal Judge died. Another friend, FDNY Captain Patrick Brown, had gone into the North Tower to rescue people and was missing. The grief was terrible, but upon waking each day I faced one beautiful truth: other friends, working in the towers and surrounding buildings, were still alive.

I had been in the North Tower on September 10th. A friend and I had met for lunch, had had a picnic in the Trinity churchyard. It was a hot day, and we sat in the shadow of downtown buildings. From the cool green shade i looked out at the ancient graves, and said what a peaceful place it was, right in the midst of downtown New York, a respite from all that crazy Wall Street energy.

Then I’d headed down into the World Trade Subway stop to catch the E train home. My friend's building was right next to the towers, and it was rocked by the next day’s explosion. She was in shock and trauma, covered in ash as she ran away, but she was alive.

Alive. In that bodega last Wednesday, the word was a prayer. Please stay alive. Please don’t jump.

News photographs, published the day after the towers collapsed, showed people falling through the air, two people holding hands in the blue sky. That’s the image I find hardest, most heartbreaking, too wrenching and unimaginable to bear.

I felt linked to the woman above me on the ledge over Park Avenue South.

Be okay, find peace, know that you are cared for.

In those charged minutes—ten, fifteen—we blurred together. Eleven years ago I lived at 1 Gramercy Park, within sight of where she stood. The apartment was on the fourth floor; the front windows faced the park, the bedroom window looked across E. 21st Street at Calvary Church. My mother was dying, I was depressed and confused, about to leave my marriage. One midnight just before I left, when I'd become unbearable to myself, I climbed out the window, sat on the sill staring down to the street. I wanted the pain of living to stop. I wanted my mother not to die. I loved my husband but I couldn't stay with him--I felt a compulsion to run away and ruin my life a little. I felt gripped by the unbearable beauty and fragility of life, the unacceptable reality of not being able to hold on forever. I wanted the courage to jump, but I didn't have it. An hour later I climbed back inside.

The towers are gone. They were so beautiful, the way the light transformed their silver surfaces. Two nights before the attack, crossing Sixth Avenue in the Village, I happened to glance right, saw them shimmer in the summer haze, pink and weightless as their lights came on like stars, took them for granted as I always did—as I always do so many things that I think will be here forever. I loved the towers, loved going to Windows on the World, bought theater tickets at the TKTS booth there because it was downtown and always less crowded than the one in Times Square. But mostly I thought they were beautiful--not so much their near-mirror-image rectangular architechture, but in the way they caught the light. The way they reflected the clouds.

Be okay: I sent my thoughts to the woman as I waited in the bodega and time ticked by.

A psychologist told me that suicides were up in New York City last week: that for some people already in emotional trouble, close to the edge, the attack on the World Trade Center had proved to be too much to handle.

I love being a New Yorker. I’ve wanted to live here for as long as I can remember. My Hartford-based father was a typewriter man. Olympia, who made the typewriters he sold and fixed, had offices at 90 West Street, before the twin towers were built, in a Cass Gilbert magical-looking building that later would sit in their shadow. When I was very young, he’d take me to New York with him, and I would wait in the car under the West Side Highway or, if it was winter and really cold, on a cracked leather sofa in the marble lobby while he did business upstairs. My feet didn’t touch the floor.

When I was fourteen and my sisters were twelve and ten, we would take the train, by ourselves, from Old Saybrook, Connecticut, to Penn Station. After hot chocolate at Rumpelmayers, we would go to the theater: Pippin, Moon for the Misbegotten, Porgy and Bess. When I was nineteen, my mentor, Brendan Gill, told me to move here. He said if I didn’t, I’d spend my life regretting it. Somehow I knew he was right.

New York has the life force running through it. It's the perfect place for the crazy, the creative, the broken, the seeking. So many of the people I love are New Yorkers. Living here I dealt with addictions, the futile ways of trying to escape pain and reality, learned to love my complicated life because it is like no other. I love the intensity here—the people, the creativity, the art, the unasked-for kindnesses, the movement, the Tourette's, the mentally ill, the genius actors, the unexpected raptors, the small neighborhood parks, the wild possibilities. To find quiet, I walk along the river or down to the harbor; I go to Central Park and look for owls.

Last Wednesday the bodega was quiet. After a long time, I walked to the plate-glass door. The woman was still up there. I could tell by the bystanders’ faces: rapt, tilted back, gripped by what was happening. Silence had fallen on this part of the city. A policeman saw me through the doorway and gestured for me to come outside. He directed me to move quickly away, along the side of the building. The September evening felt so warm, like summer; I could almost believe that everything was going to be okay.

Then the woman jumped. She fell, hit the ground at my feet with a sound that I will never forget and can’t let myself describe.

Everyone screamed. I heard voices rise, people crying, crying uncontrollably. Looking into the crowd, I saw hundreds of people reaching out, their arms outstretched up to the sky, as if they could lift the woman back up to the fifth floor. That’s how I’d felt on the 11th—wanting to lift the buildings and people and strangers holding hands back to where they’d been.

The woman lay beside me, crumpled on the sidewalk. She was broken, but her eyes looked into mine. She had dark hair. She looked about my age. Her yellow dress had tiny blue flowers printed in the cotton fabric. I saw all that, and I knelt down on the ground. I held her hand, wanting her to know she wasn’t alone as her blood ran out.

Police officers ran, tugged me away, surrounding her, doing their job. People in the crowd had pulled their arms back earthward, hugging themselves and each other, crying, no longer reaching for the sky. I was shaking and weeping, too, and I had no one to turn to.

I found myself half a block down East 21st Street, sitting in the doorway of the house where I had once lived—the red brick building, gracious and very old, at the northwest corner of Gramercy Park; I don’t remember getting there. My mother had visited me in that house. Even with her brain tumor, she had spent time with me there. She had loved New York, loved that I lived here. I’d learned about grief early, when my father died. And then my mother. Once you know grief, a part stays with you forever. Then you start to heal, and that hurts in a different way; you fear leaving them behind.

But they don’t leave you; they are with you forever. This is neither good nor bad--it just is, and the fact of them, the people you loved, exerts a tidal pull. Toward life or toward death, it's up to you.

The next morning, I woke up and thought of her: the woman in the yellow dress. That afternoon I stopped by Pat Brown’s firehouse, on East 13th Street, to leave some flowers. He had been part of Ladder 3, a rescue squad, always first into the worst fires. I wished I could tell him about the woman. He had perspective on tragedy.

On my way back home, something happened. It’s strange, but it’s part of my story, so I offer it here.

I had a vision.

A woman with peaceful eyes came to me. Her face was cloudy, and then it was clear. She was beatific and strong. Her eyes met mine with deep love and acknowledgement of what I had been through. A thread, invisible and unbreakable, had connected me to the woman. I carried the sound of her hitting the ground inside my body, and this being had come to release me. When I told my friend, a Trappist monk, he said he saw no reason not to think that she had been an angel of peace.

Today, coming out of the subway, I looked around for the towers. Like many New Yorkers, I have long used them as a compass downtown, to give me my bearings and help me figure out which way to walk, on my way to wherever I was going. Remembering they were gone, my heart caught again.

I saw a policeman. He was young, dressed in a blue uniform, standing in the sun. I walked over and asked about the woman in the yellow dress. He said she had been pronounced dead at Bellevue. He also told me the same thing the psychologist had: suicides in New York are up this week.

I don’t know the woman’s name. I don’t know her story, except that I was with her at the end. We are part of each other’s lives forever. Today the sky is blue. It is autumn, a new season. My birthday is in a few days, and a friend and I are going to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge.

Before walking away, I thanked the policeman, who was a stranger, and said, “I’m glad you’re safe.”

And he looked at me and said, “I’m glad you are too.”

At the Library

Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library

I am working on my new novel, doing most of my research at the Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library in Old Lyme, Connecticut. The 1897 brick building sits on a small hill, shaded by venerable oaks and maples, its curved granite steps and white columns graceful and inviting. Lots of writers have worked here including my friends David Handler and Dominick Dunne. We all set some of our novels in fictional versions of Lyme or Old Lyme. David's is Dorset, Dominick's was Prud'homme, and mine is Black Hall.

The old part of the library contains a reading room that feels cozy, a literary home. Its walls are lined with landscapes by plein air painters who visited town around the turn of the last century. They stayed at Miss Florence’s boarding house just a half mile along Lyme Street and set up their easels to paint the local beauty: hills of mountain laurel, cottage gardens, tidal inlets, rocky shores. Over a hundred years later, many of the scenes they chose are unchanged.

Old Lyme is located at the mouth of the Connecticut River, where it flows into Long Island Sound. There is water everywhere. Creeks, streams, marshes, and five small rivers create a particular quality of light that attracted the artists. The light is both delicate and intense, changing the landscape from second-to-second.

The Tonalists founded the Lyme Art Colony, joined later by painters who gave birth to American Impressionism. I am inspired by this place just as the artists were; it's been the setting of nearly all my novels.

The library’s reading room has a fireplace. Years ago, when I was nineteen, I wrote at this same table and often saw Dr. C. Philip Wilson, the father of a friend, sitting in an armchair beside the fire, engrossed in the New York Times or a book. It gave me comfort to see him there. He was kind and understanding, always interested in what I was writing.

Dr. Wilson was a well-known psychiatrist in New York City, and he and his family spent summers here (as my family did.) He was tall, with dark hair and a serious, almost penetrating gaze that relaxed into a warm smile. I felt him wondering what I was doing all day-every day at our small-town library instead of at college while his son, my age, was off at Princeton. He made it very easy to tell him that I had dropped out of college because of depression. As the season went on, he would ask how I was doing, and I remember how he would listen with quiet compassion, and encourage me to keep writing. I wonder whether he realized how much those conversations meant to me.

He made me feel as if I mattered. It was a tremendous gift to a troubled young writer. Over the years he and his wife would come to my readings at the library and local bookstores. I still have notes they sent me, filled with generous praise, cheering me on. Once the three of us ran into each other at the Florence Griswold Museum, for an exhibit of works by Bruce Crane. His palette was reserved, unlike the bright, sunny colors of summer gardens and sparkling blue coves used by many of his American Impressionist friends.

[image error]

Crane seemed to favor autumnal, elegiac and slightly melancholy scenes, such as one of an autumn marsh, with tawny reeds and tarnished silver waters. I remember standing with the Wilsons in front of a winter landscape—a snow field against a pewter sky, the horizon a narrow, brilliant slash of orange. We stared at it for a long time, as if watching an actual sunset, waiting for the sun to go down.

The painting, and Crane’s canvases in general, drew me in. I felt an exhilarating darkness in his work. Crane had spent years visiting Old Lyme. His wife Jeanne was hospitalized with mental illness. In 1902 he divorced her and married his stepdaughter, Jeanne’s daughter Ann.

I didn’t know those details at the time, but now I wonder if Dr. Wilson sensed Crane’s family pain, if that was why he’d regarded that sunset painting with such deep attention. Or perhaps I’m just, in retrospect, imputing the compassion he felt for me and others to the artist and his family.

Not long before Dr. Wilson died, I ran into him in the city, on Fifth Avenue. The day was sunny, and across the avenue Central Park was cool and green. I felt so happy to walk with him for a few blocks.

We caught up on news about our families and books—he too was a writer. I wish I remembered more of the details of that talk, but what stays with me was the familiar warmth, the sense of his fathomless interest and curiosity in the world. Parting, we said we'd see each other in Old Lyme.

That was the last time I saw him.

These days, working in the reading room, I miss Dr. Wilson. I glance over at the armchair by the fireplace and can still see him there, still hear his voice and feel his presence.

The loveliness of an old library is carried through time by the ghosts who loved it in their day. the stacks hold memories of the many dear readers, the many dear friends. The library holds many stories, including our own.

The reading room.