Zoe Saadia's Blog - Posts Tagged "aztecs"

The Rise of the Aztecs (part I)

Once upon a time, if you would ask the powerful Tepanecs who had dominated the fertile Mexican valley around Lake Texcoco up to the mid 14th century, the Aztecs were no more than pushy newcomers, coming out of the southwest, poor and semi-nomadic, bringing along nothing but trouble.

The lands of the Mexican Valley were amazingly rich, dotted by large city-states, with Azcapotzalco, the most powerful of them all. Of course, there was Culhuacan, boasting its Toltec origins, sprawling upon the southern side of the lake, as influential and as strong, even if Azcapotzalco’s Tepanecs refused to admit it.

The densely populated region was well under control. Still, the unabashed newcomers streamed in and managed to find themselves a very favorable piece of land on the western shore of the lake, fertile and abounded with streams. There they began to flourish, while the suspicious mood of their powerful neighbors grew proportionally. Those Aztecs would not be contented with a small role of another city state, could see the elders of Azcapotzalco. And nothing more would be tolerated.

The tension grew and, toward the end of the 13th century, Azcapotzalco rulers had expelled their troublesome new neighbors. But for the rulers of Culhuacan, it could have been the end of it. For reasons unknown, Culhuacan had decided to allocate the expelled Aztecs a little land at the empty barrens of Tizaapan. Maybe they wanted to keep an eye on those fierce groups of foreigners, to make sure they would not grow too strong. Azcapotzalco’s people were doubtful, united in their suspicions. The further those troublesome newcomers would be drove off, the better. Yet they did nothing, as the rivalry between the two powerful cities went back generations. If one decided to expel a nation, the other would support it, even if halfheartedly. So they watched carefully as the Aztecs seemed to be assimilating into the Culhuacan’s way of life.

Then the unspeakable happened! A few decades later a scandal washed the Texcoco Lake’s shores. The new ruler of Culhuacan had given his daughter to the Aztec’s ruler to marry. Or so he thought. The Aztecs promised to make her a goddess – a fate great enough even for the haughty Culhuacan princess. Well, the cultural differences showed when the princess was sacrificed in order to assist her reaching the promised status by joining the other deities. It said that the priest, wearing her flayed skin as a part of the ritual, appeared at the very festival dinner her father had honored by his presence. The Culhuacan ruler and his nobles were not amused. The roaring declaration of war could be heard in the distant southwestern realm of dwindling Anasazi, it was said.

Azcapotzalco’s Tepanecs shook their heads. Had the Culhuacan Toltecs really thought they could tame the wild beast? But now they had their own dilemmas. Should they side with Culhuacan, or would they better stay neutral? Or maybe, just to spite their old rivals, they should actually assist the despised troublemakers, as those faced a certain defeat and banishment? The warriors argued in favor of destroying the Aztecs once and for all, even if it would result in helping Culhuacan. The rulers, on the other hand, found it difficult to miss the opportunity to sneer at the old insult, when just a few decades ago, Culhuacan had sided with Aztecs against Azcapotzalco’s better judgment. Why not let them eat the meal they’ve been serving their old neighbors?

An excerpt from ‘At Road’s End’

Read a sample at: http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/...

or http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B006...

The lands of the Mexican Valley were amazingly rich, dotted by large city-states, with Azcapotzalco, the most powerful of them all. Of course, there was Culhuacan, boasting its Toltec origins, sprawling upon the southern side of the lake, as influential and as strong, even if Azcapotzalco’s Tepanecs refused to admit it.

The densely populated region was well under control. Still, the unabashed newcomers streamed in and managed to find themselves a very favorable piece of land on the western shore of the lake, fertile and abounded with streams. There they began to flourish, while the suspicious mood of their powerful neighbors grew proportionally. Those Aztecs would not be contented with a small role of another city state, could see the elders of Azcapotzalco. And nothing more would be tolerated.

The tension grew and, toward the end of the 13th century, Azcapotzalco rulers had expelled their troublesome new neighbors. But for the rulers of Culhuacan, it could have been the end of it. For reasons unknown, Culhuacan had decided to allocate the expelled Aztecs a little land at the empty barrens of Tizaapan. Maybe they wanted to keep an eye on those fierce groups of foreigners, to make sure they would not grow too strong. Azcapotzalco’s people were doubtful, united in their suspicions. The further those troublesome newcomers would be drove off, the better. Yet they did nothing, as the rivalry between the two powerful cities went back generations. If one decided to expel a nation, the other would support it, even if halfheartedly. So they watched carefully as the Aztecs seemed to be assimilating into the Culhuacan’s way of life.

Then the unspeakable happened! A few decades later a scandal washed the Texcoco Lake’s shores. The new ruler of Culhuacan had given his daughter to the Aztec’s ruler to marry. Or so he thought. The Aztecs promised to make her a goddess – a fate great enough even for the haughty Culhuacan princess. Well, the cultural differences showed when the princess was sacrificed in order to assist her reaching the promised status by joining the other deities. It said that the priest, wearing her flayed skin as a part of the ritual, appeared at the very festival dinner her father had honored by his presence. The Culhuacan ruler and his nobles were not amused. The roaring declaration of war could be heard in the distant southwestern realm of dwindling Anasazi, it was said.

Azcapotzalco’s Tepanecs shook their heads. Had the Culhuacan Toltecs really thought they could tame the wild beast? But now they had their own dilemmas. Should they side with Culhuacan, or would they better stay neutral? Or maybe, just to spite their old rivals, they should actually assist the despised troublemakers, as those faced a certain defeat and banishment? The warriors argued in favor of destroying the Aztecs once and for all, even if it would result in helping Culhuacan. The rulers, on the other hand, found it difficult to miss the opportunity to sneer at the old insult, when just a few decades ago, Culhuacan had sided with Aztecs against Azcapotzalco’s better judgment. Why not let them eat the meal they’ve been serving their old neighbors?

An excerpt from ‘At Road’s End’

She laughed. “Would I fit among the haughty warriors’ women?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t think our women are haughty. Not all of them, anyway. They come from many different places, brought to Azcapotzalco from practically everywhere. I’m sure you would eventually encounter even a woman from here. Culhuacan folk are the arrogant lot, impeccable Toltec as they are. Their women would be sure to look down on you through their narrow Toltec eyes. But the rest are all right, I guess.” He pondered for a while, remembering the annoying Culhuacan and the even-more-annoying Mexica newcomers who caused nothing but trouble. “Azcapotzalco is beautiful,” he added. “You would love that city.”

“Is it larger than Great Houses?”

He burst out laughing. “It’s like comparing a hill with a mountain.”

“I don’t believe you!”

“Then come and see for yourself.”

She shook her head with amusement. “Why those Cul-hu-a-can people are so arrogant, if they are living in your city? Are they warriors also?”

“Like us, some of them are warriors. The rest do the trade or work the land, do crafts or worship the gods. They have their own city. Culhuacan is situated on the southern side of our lake. They are arrogant bastards with no common sense. They always have to make all the mistakes. There were those pushy newcomers, from your regions by the way, but definitely not your people. Very fierce warriors. Azcapotzalco expelled them in the summer I was born. But Culhuacan? Oh no, they had to find them a piece of land, to spite us of course. And now, twenty summers later, those newcomers Mexica-Aztecs with no finesse, sacrificed a Culhuacan princess. So it means war and it only took them twenty summers to understand what we saw in the very beginning. Stupid, isn’t it?”

“They had sacrificed a princess? You mean they killed her?”

“Oh yes. The priest showed up wearing her flayed skin in the middle of the celebrative feast. The Culhuacan ruler, her father, and the rest of their nobility did not take it well.”

Sakuna gasped. “Wearing what?”

He turned to watch her, amused. “Insane, isn’t it? They promised to make her a goddess, but Culhuacan nobles didn’t think they meant literally to introduce her to the realm of the gods.”

“And to such a place you were offering to take me?”

“No, of course not. Those were the wild Aztec barbarians. Azcapotzalco priests are not flaying the sacrificial offerings and they would never touch a princess or any irrelevant person. Our gods receive nothing but the captured enemy warriors who answers all the criteria. We are completely civilized.”

She seemed as if shrinking as he talked. “You kill captured warriors? Why? And what if you get captured?”...

Read a sample at: http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/...

or http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B006...

Published on February 15, 2012 01:44

•

Tags:

ancient-mexico, azcapotzalco, aztecs, culhuacan, human-sacrifice, tepanecs, toltecs

The Rise of the Aztecs (part II)

So, in The Angry Aztecs Part I, we left the Tepanecs immersed in the dilemma.

What should the Tepanecs do with their new neighbors known as Mexica-people-from-Aztlan or the Aztecs?

The despised would-be-aristocrats got themselves into a trouble all right, enraging their previous patrons of Culhuacan. To flay a princess, of all things! Azcapotzalco’s Tepanecs shook their heads. Clearly the troublesome newcomers had no finesse. No finesse at all.

But those Aztecs had one advantage - they made great warriors. So the Tepanec rulers saw their chance. First they had launched series of raids against their neighbors in trouble, to make those understand which nation around Texcoco Lake was the most powerful to be reckoned with. Just in case it wasn’t yet clear.

Then, after thoroughly humbling the most warlike of their neighbors, they'd promptly took them under Azcapotzalco’s protection, against the wrath of Culhuacan.

The small Aztec nation was safe for now, but there was a price to pay. The Aztecs were to supply their new patrons with an unlimited amount of warriors whenever demanded.

And the Tepanecs didn’t make them wait. While the Aztecs were busy developing their new capital upon the muddy island of the great Lake, the demands began trickling in. The Azcapotzalco’s ruler had decided to turn on their historical rival – Culhuacan.

Reinforced by a horde of the warlike new allies, Azcapotzalco’s warriors had pounced on its sister-city, in less than ten summers succeeding in taking over all of their trading routes and dependable towns and villages. The surrounding districts and settlements, which had paid a tribute to Culhuacan up to these days, began sending their yearly payments to Azcapotzalco instead.

The Tepanec Empire was expanding.

An excerpt from 'The Young Jaguar', the second book in Pre-Aztec series:

read a sample on https://www.smashwords.com/books/view...

or http://www.amazon.com/Young-Jaguar-Pr...

What should the Tepanecs do with their new neighbors known as Mexica-people-from-Aztlan or the Aztecs?

The despised would-be-aristocrats got themselves into a trouble all right, enraging their previous patrons of Culhuacan. To flay a princess, of all things! Azcapotzalco’s Tepanecs shook their heads. Clearly the troublesome newcomers had no finesse. No finesse at all.

But those Aztecs had one advantage - they made great warriors. So the Tepanec rulers saw their chance. First they had launched series of raids against their neighbors in trouble, to make those understand which nation around Texcoco Lake was the most powerful to be reckoned with. Just in case it wasn’t yet clear.

Then, after thoroughly humbling the most warlike of their neighbors, they'd promptly took them under Azcapotzalco’s protection, against the wrath of Culhuacan.

The small Aztec nation was safe for now, but there was a price to pay. The Aztecs were to supply their new patrons with an unlimited amount of warriors whenever demanded.

And the Tepanecs didn’t make them wait. While the Aztecs were busy developing their new capital upon the muddy island of the great Lake, the demands began trickling in. The Azcapotzalco’s ruler had decided to turn on their historical rival – Culhuacan.

Reinforced by a horde of the warlike new allies, Azcapotzalco’s warriors had pounced on its sister-city, in less than ten summers succeeding in taking over all of their trading routes and dependable towns and villages. The surrounding districts and settlements, which had paid a tribute to Culhuacan up to these days, began sending their yearly payments to Azcapotzalco instead.

The Tepanec Empire was expanding.

An excerpt from 'The Young Jaguar', the second book in Pre-Aztec series:

Tecpatl nodded, glancing toward the wide opening in the wall, catching a glimpse of the beautiful garden outside. He could hear the water trickling in the ponds.

The eyes boring into him went flat. “Do you think Tezozomoc would make a good ruler? Would he be the right choice?”

Tecpatl returned the gaze. “It is not my place to judge on such matters.”

The heavyset man nodded and almost visibly relaxed. He was getting old, thought Tecpatl. Once upon a time this formidable man would not be readable under any circumstances.

The urge to escape the Palace welled. He thought of the spaciousness of his own gardens, of the feast that was sure to contain every delicious snack he had ever indicated as his favorite, of the ardent, exuberant welcome home which was sure to await him. He could see her, dressed in the best of her clothes, bathed and groomed, waiting for him, exalted and impatient; still beautiful, still desirable, still in love with him, still unruly and not fitting, just like fifteen summers ago when he had met her for the first time.

“You are sure Tezozomoc will give you all the commands you might desire.” The older man made it a statement.

Tecpatl forced his mind to concentrate.

“I hope he will trust me as has his father before him.”

“How long will it take to make Culhuacan crumble?”

“Not very long. Their warriors have grown soft. They are not a worthy enemy anymore.” Relieved to steer from the dangerous ground of politics, he added:

“I’ll be happy to finish them off and re-open the war against the Mayans.”

“Not the Aztecs?”

“Oh, the Aztecs make good warriors. But they are barbarians. They are few and unimportant. Culhuacan is the worthy enemy. They are our equals, our peers.”

The face of the elder man remained still, but something in the depths of the narrow eyes changed. “You do wise staying away from the Palace’s affairs. You are a warrior and you would better keep it that way.”

...

read a sample on https://www.smashwords.com/books/view...

or http://www.amazon.com/Young-Jaguar-Pr...

Published on April 22, 2012 01:33

•

Tags:

ancient-americas, ancient-mexico, aztecs, historical-fiction, mayans, mesoamerica, tepanecs

The Rise of the Aztecs (part III, Tenochtitlan)

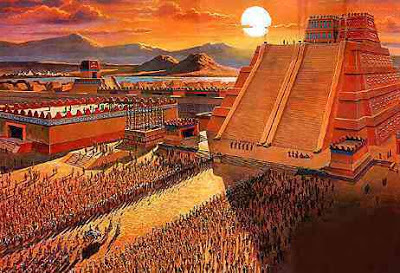

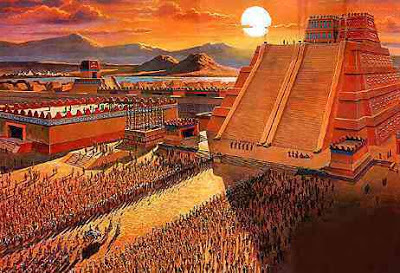

In the middle of the 15th century, Spanish conquistadors, arriving in Tenochtitlan were stunned. They had never seen anything like that before. Their homeland cities in Spain and Italy looked small, insignificant compared to Tenochtitlan.

“… When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments… great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream…”

”

Bernal Diaz del Castillo, The Conquest of New Spain

Yet only a century earlier Tenochtitlan was nothing but a swampy unimportant island-city, looked down upon by its haughty, powerful neighbors.

In the Angry Aztecs Part I we dealt with the incident of the flayed princess and the first time the Aztecs had made their powerful neighbors angry.

And then, in the Angry Aztecs Part II, they had made it to their swampy little island, relatively safe under the stern gaze of the Masters of the Valley, the Tepanecs.

So now we arrive to the end of the 14th century, when the Aztecs were somewhat better off.

Not allowed to campaign on their own, they still thrived, fighting under the Tepanec leadership, relatively safe upon the swampy little island of theirs.

Required to pay tribute every full moon, they contributed to the riches of the powerful Azcapotzalco, the Tepanec Capital. The tribute was reported to be ‘oppressive and capricious’.

Their island location has its benefits. Separated from the mainland by a certain amount of water and, thus, safe from any military surprises, the young Aztec nation was relatively safe.

Yet, this location has its disadvantages as well. Bringing materials to the rapidly growing city was difficult, so most of the houses were still reed-and-cane built. The markets were poor and the city could not even dream of building a worthwhile temple or, gods forbid, a pyramid. Large slabs of stone and marble were impossible to bring by canoes.

But the Aztecs were not only a warlike nation.

They turned out to be ambitious engineers as well.

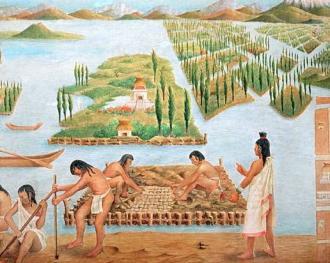

So, when Acamapichtli, a young and very vigorous ruler, was brought to lead the city, the Mexica energetic people launched into several breathtaking projects at once.

First of all, the island was enlarged artificially, with much dirt and rock. Then a causeway was built to connect it with the mainland, making it possible for the large chunks of materials to be brought into Tenochtitlan, allowing the construction of the Great Pyramid’s second stage.

Houses of cane and reed were replaced by the stone ones, temples constructed, laws made.

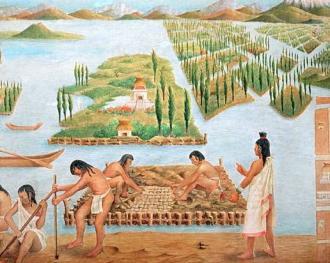

The agriculture was a problem. The island was too small to cultivate enough crops to support the rapidly growing population. Cultivating of many chinampas, the ‘floating gardens’, had helped. Yet the Aztecs needed more land. So far they were masters of their island only. They needed a permission to campaign on their own.

Well, Acamapichtli was a great diplomat. Careful not to provoke the Tepanec overlords, Tenochtitlan paid its taxes in time and when Azcapotzalco wanted a present in a form of a floating garden of beautiful flowers, a special chinampa was made in a hurry and floated over the lake straight to the shores of the Tepanec’s Capital.

Finally, after many such gestures and negotiations, the Aztecs were allowed to campaign on their own, provided their warriors kept reinforcing the Tepanec forces with the same vigor as before. The northern settlements of the lake, such as Xochimilco were attacked immediately and their lake-shores chinampas captures and put to a great use.

Tenochtitlan was growing rapidly.

An excerpt from 'The Jaguar Warrior', the third book in Pre-Aztec series:

A sample chapter can be read on http://www.amazon.com/Jaguar-Warrior-...

“… When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments… great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream…”

”

Bernal Diaz del Castillo, The Conquest of New Spain

Yet only a century earlier Tenochtitlan was nothing but a swampy unimportant island-city, looked down upon by its haughty, powerful neighbors.

In the Angry Aztecs Part I we dealt with the incident of the flayed princess and the first time the Aztecs had made their powerful neighbors angry.

And then, in the Angry Aztecs Part II, they had made it to their swampy little island, relatively safe under the stern gaze of the Masters of the Valley, the Tepanecs.

So now we arrive to the end of the 14th century, when the Aztecs were somewhat better off.

Not allowed to campaign on their own, they still thrived, fighting under the Tepanec leadership, relatively safe upon the swampy little island of theirs.

Required to pay tribute every full moon, they contributed to the riches of the powerful Azcapotzalco, the Tepanec Capital. The tribute was reported to be ‘oppressive and capricious’.

Their island location has its benefits. Separated from the mainland by a certain amount of water and, thus, safe from any military surprises, the young Aztec nation was relatively safe.

Yet, this location has its disadvantages as well. Bringing materials to the rapidly growing city was difficult, so most of the houses were still reed-and-cane built. The markets were poor and the city could not even dream of building a worthwhile temple or, gods forbid, a pyramid. Large slabs of stone and marble were impossible to bring by canoes.

But the Aztecs were not only a warlike nation.

They turned out to be ambitious engineers as well.

So, when Acamapichtli, a young and very vigorous ruler, was brought to lead the city, the Mexica energetic people launched into several breathtaking projects at once.

First of all, the island was enlarged artificially, with much dirt and rock. Then a causeway was built to connect it with the mainland, making it possible for the large chunks of materials to be brought into Tenochtitlan, allowing the construction of the Great Pyramid’s second stage.

Houses of cane and reed were replaced by the stone ones, temples constructed, laws made.

The agriculture was a problem. The island was too small to cultivate enough crops to support the rapidly growing population. Cultivating of many chinampas, the ‘floating gardens’, had helped. Yet the Aztecs needed more land. So far they were masters of their island only. They needed a permission to campaign on their own.

Well, Acamapichtli was a great diplomat. Careful not to provoke the Tepanec overlords, Tenochtitlan paid its taxes in time and when Azcapotzalco wanted a present in a form of a floating garden of beautiful flowers, a special chinampa was made in a hurry and floated over the lake straight to the shores of the Tepanec’s Capital.

Finally, after many such gestures and negotiations, the Aztecs were allowed to campaign on their own, provided their warriors kept reinforcing the Tepanec forces with the same vigor as before. The northern settlements of the lake, such as Xochimilco were attacked immediately and their lake-shores chinampas captures and put to a great use.

Tenochtitlan was growing rapidly.

An excerpt from 'The Jaguar Warrior', the third book in Pre-Aztec series:

"...

Her eyes flashed.

“I was glad, very glad! My husband is a great ruler and he is just beginning his journey. Tenochtitlan will be the greatest altepetl in the whole Valley one day. It will make Azcapotzalco look small. But by then Azcapotzalco may be just a cluster of ruins.”

He stared into her eyes, mesmerized. What she said was completely ridiculous, yet for a moment he believed her. Her eyes shone with such an intense power, radiating her hatred and more. Was she having a premonition?

He shuddered. “What you say does not make sense. Acamapichtli is an impressive man, I admit that. But he is leading a small nation that is stuck on a muddy island. His city has nowhere to grow. This altepetl cannot evolve beyond a mediocre status. You have nowhere to expand.”

“Oh, but you know so little. And you were never bright anyway. But Acamapichtli is. He is so very wise, wiser than my father even. And he is patient. He plans for twenty, two-times, three-times twenty summers from now and he works to that end. He has grand visions and he has the ability to apply his ideas patiently and carefully. He invests all his energy in his plans, but he does so smartly and patiently. You just wait and see.”

He watched her animated face. Two red spots colored the high cheekbones now and the large eyes shone brightly, almost excitedly. He had never seen her like that. Yet, what she said made his skin crawl.

“It feels too familiar,” he said tiredly. “But you should know better than to use me again. I cannot be trusted. In the end I will not betray my people. You should know it better than anyone.”

...

A sample chapter can be read on http://www.amazon.com/Jaguar-Warrior-...

Published on May 20, 2012 23:59

•

Tags:

azcapotzalco, aztecs, historical-fiction, history, mesoamerica, mexico, pre-aztec-series, tenochtitlan, tepanecs, zoe-saadia

Sold into slavery? Not the end of the world

Living in a beautiful, rich and well regulated altepetl (city-sate) of the Mexican Valley might have been a pleasant experience unless you and your family were extremely poor.

To be a pipiltin, a noble, was good. Whether residing next to the imposing cultural center, among the magnificent temples, palaces and ceremonial enclosures with a full size ball court and a beautiful plaza, or living in the colorful neighborhoods consisted of two-storey stone houses, you would have nothing to complain about. Wealthy citizens, traders, artisans and minor nobility lived well.

But closer to the marketplace and the harbor areas, the dwellings turned into lower, simpler looking constructions, sporting logs or cane-and-reed houses and much less wealth and color.

So if you were macehuatlin, a commoner, you would live around those areas, enjoying less luxury and more of a hard work. Each morning you would wake up with dawn, ready to go to work, whether to row out in order to farm your chinampa (floating man-made farms that covered considerable parts of the Lake Texcoco), or heading for your workshop to do various urban crafts. You would be expected to serve in the army too, but usually as a simple warrior, unless you managed to distinguish yourself and so start climbing the ranks.

If it happened, you would be better and better off, accumulating wealth and influence, eventually moving into a better neighborhood and acquiring slaves to make your life easier. You would be even allowed to wear jewelry like noble people, because the commoners were forbidden certain costly adornments and cotton clothes. They were not to drink octli in public and to be idle about their duties, expected to lead righteous, generally humble lives. Organized into calpulli, districts, they got by, working together, answerable to the elected head of their district, who was in his turn reporting to the representatives of the city administration.

So, just in case your prospective career as a brave, fearless warrior didn’t work, you would have to accept your lot and work diligently and with no complains, because if you succumbed to crime or gambling you may end up in a worse position, selling yourself into slavery, or sentenced to it by a court.

Tlacotin, slave, was the next lower step in the Mexican Valley societies. But as opposed to some other ancient cultures, slaves composed relatively small percentage of the general population, maybe because the slavery was almost never for life.

Slaves could be either captives taken from the conquered lands (opposed to the general belief, only the captive warriors were qualified to be sacrificial victims; no commoners or women and children faced that fate), or they were commoners who sold themselves into slavery to pay debts, survive poverty or serve their time if convicted by a court.

The crimes sentenced to slavery varied from failure to pay tribute to theft, but even a murderer could end up turning into a slave. Convicted of murder person would usually be executed, but if the family of the victim wanted him to serve as their slave, the judge might be forthcoming. Also if a man murdered a slave, the owner of the destroyed property could demand this person to serve as a slave instead.

Theft and rape often resulted in slavery, as well. And so was the crime of selling free people (like selling slaves’ children, who were legally free; in this case both the seller and buyer would be enslaved). A slave who had sold himself voluntarily might have saved money and paid the same price to gain his freedom back.

So basically the slaves were not outside the law, relatively protected from mistreatment, allowed to have families, possessions and even slaves of their own, entitled to appeal to courts in the case of mistreatment. There were even some legal benefits, like an exemption from paying a tribute and serving in the army. It was not illegal for the slaves to marry a free person and there was no social stigma attached to such unions and their fruits. The children of the slaves were born free people.

Many slaves were brought in from foreign lands, to be sold in the central markets of the large altepetls. Like with any other state activity, the government regulated this trade and it was illegal to sell an obedient slave against his or her wishes. In his turn, if the slave disobeyed his master, he was the one to be dragged into court, with the charges brought against him, backed by witnesses. A public warning would be ensued for the first time offender, but a few more of such warnings would see a slave chained with a wooden collar and sold for good. If this happened more than three time, a slave would be branded as troublesome, handed to the government for public works or sacrifice, creating the ultimate three strikes rule.

In Tenochtitlan there was another interesting law about slavery. On the way to the slave market, when the slave was about to be sold or resold, if he managed to get away and make his way to the palace without being stopped, he would be considered as free man. The only person allowed to chase that slave was the owner, or the owner’s son. No one else was to interfere, under the pain of becoming a slave himself.

An excerpt from “The Warriors' Way”, Pre-Aztec Trilogy, book #3.

If you enjoyed this post, more gossipy bits on pre-contact Mesoamerica can be found on www.precolumbianhistory.com/

At Road's End

The Young Jaguar

The Jaguar Warrior

The Warrior's Way

To be a pipiltin, a noble, was good. Whether residing next to the imposing cultural center, among the magnificent temples, palaces and ceremonial enclosures with a full size ball court and a beautiful plaza, or living in the colorful neighborhoods consisted of two-storey stone houses, you would have nothing to complain about. Wealthy citizens, traders, artisans and minor nobility lived well.

But closer to the marketplace and the harbor areas, the dwellings turned into lower, simpler looking constructions, sporting logs or cane-and-reed houses and much less wealth and color.

So if you were macehuatlin, a commoner, you would live around those areas, enjoying less luxury and more of a hard work. Each morning you would wake up with dawn, ready to go to work, whether to row out in order to farm your chinampa (floating man-made farms that covered considerable parts of the Lake Texcoco), or heading for your workshop to do various urban crafts. You would be expected to serve in the army too, but usually as a simple warrior, unless you managed to distinguish yourself and so start climbing the ranks.

If it happened, you would be better and better off, accumulating wealth and influence, eventually moving into a better neighborhood and acquiring slaves to make your life easier. You would be even allowed to wear jewelry like noble people, because the commoners were forbidden certain costly adornments and cotton clothes. They were not to drink octli in public and to be idle about their duties, expected to lead righteous, generally humble lives. Organized into calpulli, districts, they got by, working together, answerable to the elected head of their district, who was in his turn reporting to the representatives of the city administration.

So, just in case your prospective career as a brave, fearless warrior didn’t work, you would have to accept your lot and work diligently and with no complains, because if you succumbed to crime or gambling you may end up in a worse position, selling yourself into slavery, or sentenced to it by a court.

Tlacotin, slave, was the next lower step in the Mexican Valley societies. But as opposed to some other ancient cultures, slaves composed relatively small percentage of the general population, maybe because the slavery was almost never for life.

Slaves could be either captives taken from the conquered lands (opposed to the general belief, only the captive warriors were qualified to be sacrificial victims; no commoners or women and children faced that fate), or they were commoners who sold themselves into slavery to pay debts, survive poverty or serve their time if convicted by a court.

The crimes sentenced to slavery varied from failure to pay tribute to theft, but even a murderer could end up turning into a slave. Convicted of murder person would usually be executed, but if the family of the victim wanted him to serve as their slave, the judge might be forthcoming. Also if a man murdered a slave, the owner of the destroyed property could demand this person to serve as a slave instead.

Theft and rape often resulted in slavery, as well. And so was the crime of selling free people (like selling slaves’ children, who were legally free; in this case both the seller and buyer would be enslaved). A slave who had sold himself voluntarily might have saved money and paid the same price to gain his freedom back.

So basically the slaves were not outside the law, relatively protected from mistreatment, allowed to have families, possessions and even slaves of their own, entitled to appeal to courts in the case of mistreatment. There were even some legal benefits, like an exemption from paying a tribute and serving in the army. It was not illegal for the slaves to marry a free person and there was no social stigma attached to such unions and their fruits. The children of the slaves were born free people.

Many slaves were brought in from foreign lands, to be sold in the central markets of the large altepetls. Like with any other state activity, the government regulated this trade and it was illegal to sell an obedient slave against his or her wishes. In his turn, if the slave disobeyed his master, he was the one to be dragged into court, with the charges brought against him, backed by witnesses. A public warning would be ensued for the first time offender, but a few more of such warnings would see a slave chained with a wooden collar and sold for good. If this happened more than three time, a slave would be branded as troublesome, handed to the government for public works or sacrifice, creating the ultimate three strikes rule.

In Tenochtitlan there was another interesting law about slavery. On the way to the slave market, when the slave was about to be sold or resold, if he managed to get away and make his way to the palace without being stopped, he would be considered as free man. The only person allowed to chase that slave was the owner, or the owner’s son. No one else was to interfere, under the pain of becoming a slave himself.

An excerpt from “The Warriors' Way”, Pre-Aztec Trilogy, book #3.

As the grayish mist spread, Mino could make out the colorful wall behind their back and to their left. They seemed to be placed in the corner of the alley, between two marble columns. Ahead, there was a small pool and a few stone benches. Her eyes could make out a large tented podium, a dark threatening shape in the semidarkness.

The air was brightening rapidly. Hurriedly, she doubled her efforts to cut her ties against the crude pole.

“Would you stop doing that!” cried out someone behind her back.

She gasped, startled. Turning her head as far as she could, she met a pair of glaring eyes.

“Stop rocking this thing. It’s annoying,” said the man, now more calmly.

“I want to get out of here. Don’t you?”

“Where to, silly girl?” The man snorted and pushed the pole toward her, hitting her back.

“I don’t care. I’ll stop when my ties come off.”

A woman to her left laughed. “The ties are not your problem, girl. You have nowhere to go.”

“I can go home,” said Mino, resuming her rubbing.

“Where to?”

“The Smocking Mountain, around altepetl of Texcoco. The Highlands.”

“A long way!”

“I don’t care.”

“It’s the girl that was caught tonight, on our way here, isn’t it?” called another voice, its accent heavy. “You didn’t get very far the first time, little one, did you?”

Mino ignored them, working on.

“She can do that sanctuary thing,” said the woman to her left.

“What sanctuary thing?” The man with the accent snorted.

“They say if a slave manages to break free and run all the way to the Palace, he is a free man.” The woman paused, trying to turn her head and observe her audience – an impossible feat when one is tied to the pole and can only turn one’s neck.

“None of us would make it,” said another woman. “The whole market would be after such a slave.”

“But there is another rule,” said the first woman. She paused again, savoring the moment. “Only the owner of that slave or his sons is allowed to participate in the chase. None of the others. Not even the warriors.”

“Are you sure about this custom?” asked the man with the accent. “How do you know about it?”

“I know. Trust me to know,” said the woman importantly.

Mino felt the string loosening. “We don’t know the way to the Palace,” she said, her eyes on two men appearing from around the podium. She stopped moving and clasped her sweaty palms behind her back.

The other slaves fell silent as the two men approached, eyeing the tied people. One leaned forward, studying every face, one by one, carefully and thoughtfully.

If you enjoyed this post, more gossipy bits on pre-contact Mesoamerica can be found on www.precolumbianhistory.com/

At Road's End

The Young Jaguar

The Jaguar Warrior

The Warrior's Way

Published on January 08, 2016 05:45

•

Tags:

aztecs, mesoamerica, slavery