Steve Murrell's Blog, page 32

June 25, 2021

Exiles in America: Musings on Racial Injustice, Civil Unrest, and the Church

I was born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi, where I attended an all-white private prep school, played golf at a white country club, and was confirmed at an all-white Episcopal church. My sophomore year at Mississippi State University was the first time in my life to have a black friend. His name was Jerome, and I met him at a campus ministry event.

In 1984, when I was twenty-five, I moved to Manila, Philippines, in the midst of historic civil unrest. It was one year after the assassination of Ninoy Aquino, and the city streets were flooded with young people protesting the oppressive regime. Riot police, water cannons, and tear gas were a daily reality not only for the protesters but for our church ministry team who preached the gospel on the streets.

What I learned through my friendship with Jerome was how to see America differently—his experience was not as just, free, or equal as mine. And what I learned living in the Philippines was how to see myself differently—as a foreigner, a citizen of a different country.

Though I am writing about an American situation, every Christian in every nation will have to come to grips with these two realities: your national story is fatally flawed, and your true citizenship is in heaven. If we fail to see the brokenness and injustice of our own nation, we cannot become agents of justice and reconciliation. But if we fail to understand that we are actually citizens of heaven, we will continually confuse earthly kingdoms with the Kingdom of Heaven and become disillusioned when perfect justice and peace elude us.

I’ve been reminded of these two realities as I have watched the news unfold over the last few days. The violent, senseless, and unjust killing of George Floyd at the hands of a white police officer in Minneapolis has served as another painful reminder of the sin of racism in America. And the subsequent civil unrest—fueled by decades of disappointment and disillusionment with the American dream—has reminded me that America is more like Babylon than the new Jerusalem.

I understand that this claim may be offensive to both black and white Christians for different reasons.

My white brothers and sisters, who tend to see America as the Promised Land (a place of freedom and prosperity), may take exception to the unflattering comparison of America with Babylon. While there is much to be grateful for in American history, there is also much to grieve. The reality is that America, no matter how just and democratic, will always be closer to Babylon than the new Jerusalem.

My black brothers and sisters, who might tend to see America as Egypt (a place of bondage and oppression), may take exception to the comparison of America to Babylon because Israel’s freedom from Babylonian captivity was much less decisive and complete than the Exodus. People may see this as a tacit argument for being satisfied with the status quo. But the Israelites were never called to be satisfied with their captivity (see Psalm 137); they were called to seek the peace of the city (Babylon) while continuing to long for their true homeland (Jerusalem).

When I think about my multiple decades in the Philippines, I have lived through four democratic transfers of presidential power, two (bloodless) revolutions (1986 and 2001), and one impeachment. As a longtime resident of the Philippines, I have been affected by the political ups and downs of the nation. I have rejoiced in the Philippines’ successes and grieved at its injustices and failures. But I have done so as a foreigner. My joy and my sadness in the Philippine story is not rooted in nationalism but rather in my love for the Filipino people and my commitment to the call of God.

This, I would argue, is how every American Christian should relate to the ups and downs of the American experiment. We should seek the peace of the city and nation—not because our ultimate destiny is wrapped up in the American story but because God in his providence has put us here and called us to love our neighbor. When we adopt this exilic mindset, we will be able to seek justice and peace for the right reasons and with the right perspective.

But we can’t do it alone.

I, as a white man raised in the South, could not see the inequity and injustice all around me until I met Jerome. And I don’t think that Jerome, who had experienced inequity and injustice growing up in segregated Mississippi, could have truly been reconciled until he found himself in a campus ministry with white people who loved him like a brother.

In turbulent times like these, it can be easy for Christians (both black and white) to give up on multiethnic church community. Relationships are always easier when we pursue them with people who look and think like us—fewer misunderstandings, fewer awkward social media posts (or non-posts), fewer offenses to work through.

But God has called us be a peculiar people—a people of every nation, tribe, and tongue. A community of the redeemed who are committed to the ministry of reconciliation and called to be ambassadors of a different kingdom.

While we live here as exiles, let us not lose heart and let us pray and live these words of our king and redeemer Jesus: your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as is it in heaven.

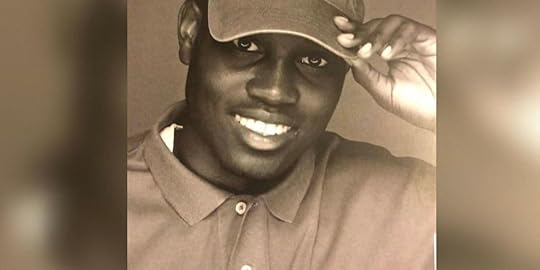

Ahmaud Arbery and John Murrell: Personal Reflections on Injustice, History, and Hope

As the leader of a global movement, I make it a point not to comment on national issues. However, as has been the case with many other current events, my son, William, and I recently had a conversation about the violent killing of Ahmaud Arbery. I asked him to share his thoughts in light of a surprisingly relevant piece of Murrell family history.

William S. Murrell, Jr.—For those unfamiliar with the tragic death of Ahmaud Arbery (who was shot while jogging near his home), I recommend reading this article for a detailed analysis of the facts as we know them today.

As I’ve grappled with how to respond (privately and publicly) to yet another needless killing of an unarmed black man, I’ve found strange solace from the biography of a distant ancestor of mine (Same family tree, but a different branch) named John Murrell—who became (in)famous in the 1820s and 30s as a bandit, horse thief, and slave-stealer in the southern United States.

As a slave-stealer, Murrell would help African American slaves escape from their masters and would pretend to be a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad. However, the journey north to freedom had a twist: Murrell (with the cooperation of the recently freed slave) would resell the slave to a new master and then help them escape a few days later. Murrell would do this several times on the journey north with the promise that when they reached freedom, he would split the profits with the newly freed slave so that he or she would have money to start their new life. But Murrell never came through. Either he would abandon the slave with their new master if things got too complicated; or worse, he would kill the nameless “negro” once they got close to the border.

Reading and reflecting on Murrell’s biography has helped me process Ahmaud Arbery’s death in at least four ways.

First, Murrell’s biography has provided me with a horrifying yet salutary reminder of human depravity and sin. Since my last name is not very common, it has been surreal to see the name “Murrell” referred to so frequently as the agent of such violence and evil (murder, robbery, slavery, rape, etc). While reading the accounts of Murrell’s breathtakingly depraved deeds—particularly towards black people—I find myself subconsciously trying to disassociate from my ancestor and his sins. But every time I make this mental move, I sense the Holy Spirit reminding me that his blood runs in my veins. Apart from God’s grace, I am no more righteous than John Murrell and just as capable of unspeakable evil. Thus, I have begun reading Murrell’s biography as a picture of who I could have been had I lived in Tennessee in 1820 and not been redeemed by Jesus. To make matters even more personal, one of John Murrell’s main accomplices was his older brother, William S. Murrell. (To clarify, this is just coincidence; I was not named after him, nor was my father. But the coincidental name match was surreal nonetheless.)

Second, Murrell’s biography reminds me that sadly, Christianity can become a cover for racism and injustice. It turns out that besides being a bandit and a slave-stealer, John Murrell also had another life as an imposter Methodist circuit rider. On one day, we find Murrell preaching at a camp meeting (or outdoor revival) in Kentucky. On the next, we find him stealing the revival participants’ horses and slaves and heading to the next town. For Murrell, the persona of the Methodist preacher was the perfect cover for his other work. It gave him credibility with local communities as he traveled around the South. Though Murrell’s duplicity may have been more blatant than most, for generations, white Americans have hidden their racism behind a veneer of religion. For too long, Christians have dressed up their racism with theological arguments and the general perception of being respectable “God-fearing” citizens—which is how some defenders are characterizing Ahmaud Arbery’s killers.

Third, Murrell’s biography provides me with historical perspective on how easily and frequently our societies (whether in the nineteenth or twenty-first century) devalue human life. When Murrell was finally brought to justice in 1834, it was not for murdering African-American slaves but for stealing “property” from white slave owners. Throughout his biography, written shortly after his death, it’s amazing how inconsequential Murrell’s black victims appear in the eyes of the white storyteller. While the murders of black men and women are never condoned or celebrated by Murrell’s nineteenth-century biographer, his black victims are also never mourned—even named. I imagine that this historic devaluing of black lives (and deaths) is why events like the killing of Ahmaud Arbery can be so traumatic for African Americans today. It reminds them that their lives (in the eyes of some) continue to be undervalued nearly two centuries after emancipation. Remember, Arbery was killed on February 23, 2020, and no one was arrested or investigated, even though the police on scene knew who pulled the trigger. It was only after a video of the killing surfaced in early May that arrests and investigations were renewed.

Finally, Murrell’s biography offers me hope for justice in our day. I was fascinated to discover that Murrell’s capture in 1834 came at the hands of Tom Brannon, a black slave from Florence, Alabama, who outsmarted Murrell at his own game. Murrell had kidnapped Brannon and tried to enlist him in his grand scheme to start a slave revolt in the south. However, Brannon double-crossed Murrell and delivered him to the authorities, who rewarded him with the $100 bounty (a lot of money in 1834) for aiding in the capture of the most-wanted man in America. At our present moment when justice so often seems to elude the black community, the story of Tom Brannon gives me hope that justice will be served in the case of Ahmaud Arbery.

Not only does Murrell’s biography give me hope for justice for Ahmaud Arbery and his family, it also gives me hope for the redemption of his killers.

According to Murrell’s biography, during his ten years in prison, Murrell repented and experienced a genuine religious conversion. He was regularly visited by (real) Methodists ministers who preached the gospel to a broken man who had spent his entire adult life lying, stealing, and killing—all under the guise of being a Methodist preacher. When he was released from prison in 1844, he became a blacksmith (a trade he learned in prison), and literally spent the remaining months of his life (before dying of tuberculosis) turning swords into ploughshares. Likewise, regarding Ahmaud Arbery’s killers, I am praying for justice to prevail. I am also praying for their redemption and reconciliation.

If God can redeem John Murrell, he can redeem anyone. And if God can bring both justice and redemption in 1844, he can do it in 2020.

May 27, 2021

Culture of Honor

I have had a few conversations recently with leaders about building a culture of honor among staff. How do we build a biblical culture of honor—one not just built on status or position but on valuing one another?

The foundation for building a culture of honor is to honor our fathers and mothers. Many people could write a positive version of their childhood that would be entirely accurate, but they could also write a negative version that would be true. Honoring imperfect fathers and mothers requires actively choosing to forgive the bad and remember the good. I think those principles also apply to building a culture of honor in a staff.

May 20, 2021

Tasteless Salt and Invisible Light

Experts say that the strongest cue for waking up isn’t sound but light. Our brains process light as the surest sign that it’s time to be awake.

Salt, something that most people consider to be a common household item, is a useful substance for many things including flavoring, cleansing, and preserving.

Jesus told his original disciples, “You are the salt of the earth . . . You are the light of the world” (Matthew 5:13–16).

May 12, 2021

How Are Your Relationships?

A few weeks ago, I had the honor of speaking with Dave Hess, who leads campus ministry efforts for Freedom Church in Philadelphia and serves as a regional director for Every Nation Campus North America. Dave asked me to join his podcast to speak about discipleship and leadership.

When I asked Dave what he thought might be most helpful for leaders to hear right now, he mentioned our discussion on cultivating and maintaining friendships. Good relationships are foundational to our ability to sustain in life and ministry—with God, of course, but also with other people. But maintaining long-term relationships is almost always challenging. At some point or another, many of these relationships will involve two difficult things: repentance and forgiveness.

I hope my discussion with Dave will encourage you as you seek and build long-term relationships.

April 29, 2021

When to Break the Rules

As leaders, we tend to love the type of church or ministry members who are “all in.” The more committed, the better, right?

Maybe; maybe not. After reading Mark 2–3 the other day, I realized that in the gospels, those who often received the harshest rebuke from Jesus were the quintessential “all in” types—the Pharisees.

The sobering reality for all of us is that those who are deeply committed to God’s word are still at risk of slipping into Pharisaical tendencies. Our love of policy and process can sometimes get in the way of the mission.

As I reflect on Jesus’ example in this passage and his harsh rebuke of the Pharisees, I see the following:

Pharisees love rules but break people. Jesus loves people but breaks rules.I hope you’ll consider these questions for your church, campus ministry, or team that you lead:

Who is empowered to make exceptions to the rule?Who is empowered to bend and break the rules?Which rules can never be broken?April 22, 2021

Top Priority: Worship or Mission?

There is a tension between worship and mission. Many of you have probably experienced this tension at some point in time as you were figuring out a next step or direction for your life. Do we wait on the Lord until we get clear direction, or do we go on mission and trust God to direct us as we go?

I think it’s both. Matthew 28:5–7 records the story of Mary Magdalene and the other Mary, who got clear direction as they went and encountered Jesus as they went.

April 15, 2021

When to Ignore Best Practices

There are aisles and aisles of books dedicated to explaining best practices for organizations, businesses, ministries, etc. I’m grateful for them because they can be helpful and informative.

But there are also times when we should completely ignore best practices—when blindly following best practices could push us away from God’s call rather than towards it.

How?

When Deborah and I planted Victory in the Philippines in 1984, we knew that God had called us to reach the future leaders of the Philippines. Because of that call and because we knew the largest concentration of future leaders is on the university campus, we planted Victory in the very center of Manila’s University-Belt. Many Filipino pastors and well-meaning American missionaries told us that the U-Belt was the worst place in Metro Manila to plant a church (and they were probably right). But we knew we were called to reach future leaders, so we ignored good advice and best practices.

April 8, 2021

Following a G.O.A.T.

As a ministry or church leader, can you imagine following the G.O.A.T.—the Greatest Of All Time? Can you imagine having to measure up to the standards and expectations this leader set?

When I look at leadership G.O.A.T.s in the Bible—those who were fully human and fallible leaders—I immediately think of Moses. He responded to the call of God, delivered God’s people out of slavery, and founded a nation. Imagine being Joshua, having to follow that kind of accomplishment. But we don’t see a decline in leadership under Joshua. Why?

April 1, 2021

When Hope is too Small

First century Jews expected their messiah to ride a chariot, or maybe a warhorse, but not a young donkey. Then here comes Jesus on a donkey. I imagine the disciples were disappointed, maybe embarrassed.

Like most Jews in that day, the disciples hoped for a messiah who would bring nationalistic, political, and economic salvation. But Jesus offered “shalom”—not military peace with the Roman army, but internal and eternal peace with God, which is much greater than their temporal and nationalistic hope.

If the disciples were indeed disappointed to see their messiah riding a young donkey rather than a warhorse, then they were disappointed because their hope was too small.

Steve Murrell's Blog

- Steve Murrell's profile

- 53 followers