Robyn Ryle's Blog, page 4

July 8, 2017

Diary of a Novel: July 8

Traveling makes me nervous. Which isn’t to say I don’t enjoy traveling. I do. But also the thought of stepping out of my familiar front door out into the world is also always a little bit terrifying.

It always helps to carry some bit of home with me. Ideally, that would be my cat, but traveling makes cats even more nervous than it makes me.

Sometimes when I go to writing conferences and I’m by myself, I take my yoga mat with me. When I’m in a period of regular practice, the yoga mat itself is home. Which is to say not just that the yoga mat is a physical thing that lives in my house, but that the practice itself is home. The act of doing yoga is a refuge. It is safe and familiar.

In the last six months or so, I’ve made my writing into a practice. It’s something I do pretty much every day. This doesn’t make it easy. It just makes it easier. The hardest part is almost always making myself sit down in the chair. After that, the hardest part is keeping myself in the chair.

I can’t take my writing chair with me on the road. I can’t take the coffee shop with me, which is my other writing space. I can, of course, take my laptop. But more than that, I can take the practice. The comfort of something I do every day. Writing can become a refuge, like my yoga mat. Something safe and familiar. A tiny corner of orderliness in the middle of the chaos.

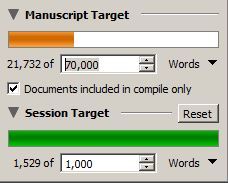

So we’re off to the beach soon and I still have about 15,000 words of the novel left to write. That’s assuming it doesn’t take more than 70,000 words to get the story fully told, which it might. The only deadline is my own. Part of me wanted to get the novel done before heading to the beach. Part of me just very much wants to get this draft done. In the last part of writing a novel, every other thing you could be doing starts to seem so much better. Wouldn’t it be so much more fun to be editing that other thing? Or to be weeding? Or to be working on fall course syllabi? Wouldn’t anything be better than another day of this?

So we’re off to the beach soon and I still have about 15,000 words of the novel left to write. That’s assuming it doesn’t take more than 70,000 words to get the story fully told, which it might. The only deadline is my own. Part of me wanted to get the novel done before heading to the beach. Part of me just very much wants to get this draft done. In the last part of writing a novel, every other thing you could be doing starts to seem so much better. Wouldn’t it be so much more fun to be editing that other thing? Or to be weeding? Or to be working on fall course syllabi? Wouldn’t anything be better than another day of this?

I’ve been pushing myself the last few days. A sort of desperate scramble to get more written. Yesterday I wrote almost 3,000 words. It felt like writing out of a daze. Writing a draft is like putting up scaffolding. You’re just testing out how it’s all going to hang together. You’re never really sure if even of your decisions are going to make much sense down the road.

This morning, I re-read what I’d written yesterday. That’s almost always how I start in the morning. It’s sort of like dipping your toes into the water before diving in head-first. And it turned out those 3,000 words from yesterday were pretty good. There were moments that made me smile and moments that made me a little sad. Even if it felt like I was in a daze at the time, it was better to have written the words than not.

Writing is like that. It’s always better to have written than not to have written. It’s always better to give the voices a moment to scream their crazy shit and then move on. It’s always better to have stepped through the front door and out into the world.

June 18, 2017

Diary of a Novel: June 18

Life is weird. Sometimes it’s weird in ways that make you feel like you can barely stand up under the weight of it. And then sometimes it’s weird in ways that lift you up and feel a little bit like flying.

Life is weird. Sometimes it’s weird in ways that make you feel like you can barely stand up under the weight of it. And then sometimes it’s weird in ways that lift you up and feel a little bit like flying.

I should have been almost done with the novel I’m working on by now, but another writing project took precedence the last week or so. That’s all okay. The other writing project isn’t fiction and sometimes it’s good to shift your head into an entirely different sort of mode. The novel will still be there, waiting for me.

And when I get back to it, the novel will be sort of new, which is always a nice thing. Time is an indispensable tool for a writer. More often than you think, the best thing you can do for your writing is just to leave it the hell alone. Walk away. Pretend it doesn’t exist. Forget you ever wrote it. Let it marinate in the passage of time and when you go back to it, you’ll be able to see it more clearly. You’ll be able to see what’s good and also where you went wrong. You’ll see the things you were doing without really knowing you were doing them at all.

So time off is good and in the moments when I’ve not been working on the novel, I’ve taken to picking up my guitar again. That’s something I haven’t done for years, after a period in which I acquired no less than eight musical instruments in the space of six months or so. And then I let them gather dust.

But here’s what happened. I went to update our phones–my husband’s and my own. The two new phones looked exactly alike, and so the woman at the store put a guitar pick in one of the boxes so I’d know which one was mine. The pick says, “Thank you for picking TCC.” I don’t know what TCC is. The store, I guess?

At any rate, there’s a guitar pick which ends up on our dining room table for a few weeks. And then somehow it migrates to the bookshelves next to where my guitar sits. Pick + guitar. Why not? Sometimes that’s what it takes. A random drift of objects in your house.

A minor is my favorite chord. When I play an A minor chord, it satisfies a need I’m not even aware I have most of the time.

Playing guitar is an act that must be written onto your body. Your fingers have to develop calluses as they press on the strings. I have always loved this about the guitar. The music is tattooed onto your skin. I like the feeling of rubbing my fingers across the calluses over and over again. As they thicken, I feel myself joining a family. A cult. A community. I feel myself stepping inside a world filled with people who make music–people who have always been there for me.

Writing and playing music are very different but not completely unrelated. Jason Isbell writes stories and lines that I would kill to have come up with. “She didn’t want a better attitude.” “Nothing but the blue sky in his eyes.” “These 5A bastards run a shallow cross.” But you can’t take those words away from the music. They belong to each other.

Music feels older and deeper than words. We sang before we had language. We’re not the only ones who sing. The universe hums and croons. I feel a little bit of it with the guitar held tight against me when I play an A minor chord.

June 5, 2017

Diary of a Novel: June 5

Life changes so fast. Nothing stays the same. As a Buddhist, this is one of the keys to happiness. We must contemplate impermanence. That person you’re angry at right now? Ask yourself where you’ll both be in 300 years. Dust. You’ll both be dust. Sooner than that, even. What’s the point of your anger now?

I like Buddhism because it doesn’t attempt to explain why things are impermanent. That’s not really the important question and you’re probably not going to find happiness trying to figure it out. All the answers I’ve heard are so stupid. “It was/wasn’t meant to be.” “It’s part of god’s plan.” Nah, I don’t buy it.

Things are impermanent. What do we do in the face of that inevitability? Try to live in the full knowledge of it every moment. Every day. How do you interact with the people in your life knowing that it’s all impermanent? You love them hard. You make sure they know how important they are to the world. You say all the things you need to say now.

Things are impermanent. What do we do in the face of that inevitability? Try to live in the full knowledge of it every moment. Every day. How do you interact with the people in your life knowing that it’s all impermanent? You love them hard. You make sure they know how important they are to the world. You say all the things you need to say now.

Some days things will be too bad to write and that’s okay. It’ll be there waiting for you when you’re ready to come back. Writing is impermanent, too. When I’m drafting a novel, I can’t wait to be done. When I finish, I miss it.

Maybe some of the things you write will survive after you’re gone. Maybe not. In 300 years, it’ll probably still be dust. If you can go on writing even in the face of that, then you’ve earned the right to really call yourself a writer.

Why are you doing it, then? Not for money. You have about the same chances of being struck by lightning as you do of making a living solely as a writer. Not for fame. Same chances. You don’t know. It brings you joy sometimes. It’s a place of solace. Sometimes the ‘why’ is overrated.

June 1, 2017

Diary of a Novel: June 1

I’ve never been a writer who talks a whole lot about the process of writing. Maybe that’s because I don’t have a local writing community. I have lots of great writing friends scattered geographically, but no one really available for a chat in the coffee shop. This could be good or bad. I really can’t say for sure.

Also, I read once that my favorite writer, Elizabeth Strout, doesn’t hang out with other writers. I still don’t know what to make of this. Is it a kind of self-hatred? Do I not want to belong to any club that would have me as a member?

And then, sometimes I suspect that talking about writing can get in the way of actual writing. After all, the actual writing is lonely. It’s a slog. As one of my writing friend says, it’s a long swim across the channel. In stormy weather. Alone.

I don’t know if this is an attempt to relieve some of that loneliness. It might just be a substitute for social media like Facebook and Twitter, which I have mostly given up in the past few weeks. Mostly, there are things I think about while I’m writing that seem like thoughts that should be shared. So I’m sharing them.

I’m working on a novel right now. It’s not my first. I’m reading an author right now who wrote thirteen novels before his first got published. I’m not there yet. I might get close. Let’s just say it’s not the first novel I’ve written.

It’s summer and I’m a professor, so I have all day to write if I choose. I don’t recommend that.

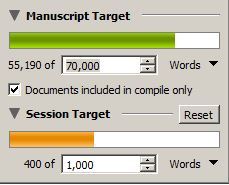

I’m about 22,000 words in. If a novel is 70,000 words, I’m about a third of the way there. In Scrivener, which is the program I use for writing, I’ve moved from red to orange in the Manuscript Target window. Moving from red to orange is such a victory.

I am drafting this novel. Pulling it down out of thin air. I give a character a name and off we go. It is in turn exhilarating and terrifying. I spend a lot of time in the coffee shop staring out the window, which is its own kind of writing.

I am drafting this novel. Pulling it down out of thin air. I give a character a name and off we go. It is in turn exhilarating and terrifying. I spend a lot of time in the coffee shop staring out the window, which is its own kind of writing.

I don’t have any deadlines. Just the sense that this is what I want to be doing. I write pretty much every day because I think of writing as a practice. You have to do it and do it and do it so that the not doing of it feels strange. The longer you stay away, the harder it is to come back.

One of the hard things about drafting a novel is that it’s kind of like having first-year advisees. First-years need a lot of attention, but you don’t know them at all. So the people you’re supposed to devote the most time and energy toward are the people you know the least.

It’s sort of the same thing with your characters in the first draft. They need a lot of attention, but you haven’t figured out exactly who they are yet.

On the other hand, the magic of it. The pure magic. You make a person. You create them out of words. And even if just one other person reads it, hopefully you’ve made those people real. Hell, even if you’re the only person who ever reads it. You did that. You made a person and a world and a story. That is magic. You are magic.

May 2, 2017

The loneliness of first base

We went to see a Reds game last night and sat behind first base. The seats were as close as I’ve ever been to a Major League field. If I walked down a few steps, I would have been on the same level as Joey Votto, the Reds first basemen and my favorite player. More than my favorite player, really. Joey is a bit of an obsession.

At an NFL game, at least the ones I’ve been to, you’re never at the same level as the athletes. You’re looking down on them from above. I think it says a lot that in baseball, you could step across a low wall and be on the field beside the players.

We went with my parents and my dad told a story at dinner about going to see a game in Crosley Field for the first time. He couldn’t believe how green it was. Every time you forget that. You forget that the field is even brighter in person than it is on TV. You forget that baseball is still something that’s worth doing in person. It’s worth it to be there.

It was a small crowd—cold on a Monday night in early May. It didn’t feel like baseball weather yet. There was room to move around and get comfortable in our seats. It felt a bit like we had the place to ourselves.

I watched Joey at first base. He’s why I picked those seats. My mom pointed out the way he keeps his sunflower seeds in his back pocket. He pulls some out between pitches and tosses some in his mouth.

When there’s no one on first, he stands between first and second. He crouches down as the pitcher winds up. Then relaxes if the ball’s not hit. He does this over and over again.

If there’s a runner on first, Joey stands next to him. Sometimes they chat. From our seats, I could watch the pitcher, Amir Garrett, stare at the runner on first before each pitch. I couldn’t see Joey’s face looking back at Garrett. I wonder what his expression was. Did he smile at Garrett? Make some kind of signal of encouragement? Was there a camaraderie? Did their eyes even meet? Or did Joey just have that usual look of intensity, waiting to see if Garrett would try to catch the runner off the base? Poised and waiting and ready.

This is what Joey Votto does in a game. He stands around. He grabs some sunflower seeds out of his back pocket. He throws them in his mouth. He spits out the shells. He crouches down for the pitch. Runs to the base if it’s a hit. Waits for the ball to come to him. Repeat, repeat, repeat, with time in the dugout or at bat in between.

The morning after the game, there’s a guy working on installing a new air conditioner at the church next door. All morning, there’s the sound of his hammering. He’s in a shallow hole he’s dug, banging and then stopping. Banging and then stopping. He sees me from our kitchen window at one point and smiles. He’s young and alone. I think of Joey.

The morning after the game, there’s a guy working on installing a new air conditioner at the church next door. All morning, there’s the sound of his hammering. He’s in a shallow hole he’s dug, banging and then stopping. Banging and then stopping. He sees me from our kitchen window at one point and smiles. He’s young and alone. I think of Joey.

“First base is the loneliest place,” I tell my husband.

“I think the outfield is lonelier,” he says. “There’s no one else around.”

But I disagree. Sometimes you’re loneliest in the midst of people. A base runner, the first base coach. The pitcher staring at you before every pitch.

Sometimes you’re loneliest when so much depends on a small, repetitive thing. Crouch. Watch. Step to first. Stretch out your glove with one foot on the base. Catch.

Repeat, repeat, repeat. Joey makes it look easy, but that easiness is a place no one else can go.

April 28, 2017

Preserving Places: The Coffee Shop and the Corner Store

I’m here because I’m a sociologist who studies places and community, but my love for places came before my love for sociology. I loved places before I even knew what sociology was. I was a placist before I was a sociologist.

What is a placist? Placist is a word invented by a friend of mine-Sara Patterson-who is a historian of religion and is also obsessed with place. She’s obsessed with place and religion…with sacred places. She studies how spaces come to be seen as sacred. Placist is not in the dictionary….yet. I give you all permission to start using it freely.

Being placist is an ideological stance. It is a conviction, a passion, a movement you choose to align yourself with. It is an “ist.” People will tell you ‘ists’ are bad, but don’t believe them. I think we all need to embrace and be proud of own our passions. I am a feminist. An environmentalist. An anti-racist. A place-ist. I am unapologetically committed to places.

As a sociologist, I’m interested in how places shape social life. So, I ask questions about how places shape our social interactions and the kind of communities in which we live. I’m interested in how places create or contribute to existing inequalities and in how places shape our identities, the way we understand who we are and how we fit into the world. These are the kinds of questions sociologists ask.

I want to talk to you about being a placist and being a sociologist using two the places that have been most important to me—the corner store and the coffee shop. So I’m going to start with the place I’m from and end with the place I live now. In between, I’ll talk about what we’re discovering about the wide-ranging effects of the places we live in—how they affect our old age, our childhood, our friendships and our health.

The Corner Store

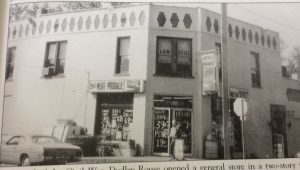

The “corner store”, or Smith’s Market, in Burlington, Kentucky. 1970s

The corner store in Burlington, Kentucky, taught me how to love a place and what happens when that place is lost. The two most important landscapes of my childhood were the woods around the house where I grew up and the streets of downtown Burlington. My grandmother lived in downtown Burlington and my sister and I spent a lot of time at her house and a lot of time walking to the corner store. And yes, we mostly went there for candy.

If you grew up in a town with a corner store, or anything like it, you know that it wasn’t all about the candy. Or the ice cream. Or the soda. Or whatever the particular treat was for you. Of course, the candy was part of it. But a corner store with candy is also a destination for children, a place to go.

Going to the corner store is all about that experience of independence and exploration and possibility. Anything could happen in the two blocks between grandma’s house and the corner store. You could run into people, some you’re happy about running into, and some you’re not so happy about running into. You could take any number of different routes to the corner store, some of them more acceptable to your grandmother than others. You had a measure of independence and freedom from adult supervision before you turned sixteen and got a driver’s license.

In a small town like Burlington when I was growing up, we didn’t worry about something dangerous happening on the way to the corner store. That wasn’t because there was less crime back then. In fact, the crime rate in the U.S. has decreased since I was a kid.

We worried less in part because we did understand what it meant to see places as caretakers. Good places create caretakers. They create a community of caretakers, and therefore a safe environment for children. The sociologist William H. Whyte in his study of small urban spaces found that the best predictor of the safety of a place was the presence of women. If you find women in a place, it is generally a safe space to be. I would say the same of children. If children can walk around in your town on their own, you are probably in a safe community.

About the time I was in graduate school, the corner store closed its doors. Then the church down the street bought it and tore it down. Can you guess what they put in its place? Think of the Joni Mitchell song if you need a clue. A parking lot. Of course. There is never a shortage of parking lots in the world. It seems we believe that we could always use one more.

Now it’s almost 15 years later, and a lot of the people who made up that community are gone and so is the corner store. Communities shift and change. People move in and people move in out. People are born and people die. If you preserve places, though, something of the community goes on. Research tells us that our minds and our memories are spatially oriented. The best way to remember something is to create a replica of a place you know inside your mind and put the memory there. It comes as no surprise, then, that places serve as physical markers for our memories, our identities and our communities.

The corner store taught me what it was to love a place and then what it was to lose it.

A sociological interlude

I left Burlington for college and then graduate school where I learned what a sociological perspective on place might look like. The more I learned, the more I became convinced that places were more than just the physical repositories of memories and communities. They could actively make us healthier and happier.

For years, I was convinced that many of the places we were creating were failing us. Increasingly, research has shown this to be true. This is just a small sampling of the research that’s out there about the effects of places on our lives and well-being.

Places and aging

The idea of aging in place has been around for a long time. It describes the advantages for the elderly of being able to stay in their existing communities instead of having to move to a home or other group facility. It only works if the place you’re already in is a good place in which to age, and research shows that many of our existing places are not.

The Population Reference Bureau compiled research on neighborhood effects on aging. They identified six important factors for making aging in place beneficial for seniors. These include that the place be walkable, accessible, compact, safe, have plentiful resources and have healthy air. When a place meets these criteria, it has wide-ranging effects for the elderly, from their ability to get around to their cognitive functioning. Places are important in shaping what our health and well-being will be as we age.

Places and friendship

Places shape the kinds of interactions we have and therefore the types of relationships that are formed. Research on friendship tells us that among adults in the United States, the ability to form friendships seems to be getting harder and harder. In interviews, adults describe “being” there as an important quality in friendship, but admit that they spend little time with their friends, even when they live relatively close.

Repeated spontaneous contact might explain why adults today struggle with forming and maintaining meaningful friendships. Repeated spontaneous contact is that process of running into someone over and over again and is a necessary part of forming friendships. It happens easily in high school, college or graduate school, where you live together, eat together and attend classes together. It gets harder as we get older.

If you have a partner, a job and children, where in most of our modern lives would we have repeated spontaneous contact with people? When we’re not working, we spend an average of 290 hours per year on the road, or the equivalent of seven, full forty-hour work weeks driving. There’s not much repeated spontaneous contact that happens in a car. When we design places that force us to spend most of our time driving, our ability to form and maintain friendships as adults suffers.

Places with a healthy walkshed are more likely to produce this repeated spontaneous contact so important to friendship formation. A walkshed is an area in which a community of people regularly mingles doing errands, walking their dogs, playing in the parks, going to school and work, etc. When we design places where people are likely to run into each often outside of the confined space of their cars, we make friendship easier.

Places and addiction

What could the design of places and addiction possibly have in common? The dominant understanding of addiction is that it’s a chemical process. We become addicted to drugs because of the effects they have on our brains. But some research suggests that addiction is less about chemistry and more about our interactions.

In his book, Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the Drug War, Johann Hari sets out to learn about the cause of addiction. He comes upon the research of Bruce Alexander, a psychology professor in Vancouver. Alexander knew that if a lone rat in a cage is given water laced with heroine or cocaine as well as plain water, the rat will choose to drink the drug-laced water until it dies. In other words, the rat will become addicted. But what if the rat was in a different cage?

Alexander put rats together in what he called Rat Park. Rat Park had other rats as well as colored balls, good rat food, plenty of tunnels and lots of rat friends. The rats in Rat Park were offered drug-laced and plain water. They sampled the drug-laced water, but they didn’t become addicted. They didn’t drink it until they died. None of the rats in Rat Park became heavy users while all of the rats alone in their cage did. Alexander concluded, it’s not the drugs that cause addiction, but the cage.

In other words, humans naturally seek to bond and we usually fulfill that need with other humans. But when we find ourselves in the cage by ourselves—alone and without another human to connect with—we’re more likely to turn to drugs or alcohol or gambling or shopping as a substitute for that human connection. Surely if we live in places that are more like the human equivalent of Rat Park—places that encourage connection and interaction—we would see less addiction.

The coffee shop

A good place should be walkable, accessible and with plentiful resources for the elderly. It should have a healthy walkshed to help adults form friendships. It should be a place that encourages interaction and connection. What would such a place look like?

The coffee shop, or Red Roaster Coffee Shop and Eatery, in Madison

After I left Burlington, I got my Ph.D. and took a job at Hanover College, which is just down the road from Madison, Indiana. This is the part of the speech where I show you pictures and sell you on how great Madison is. I wish I could tell you that I was very intentional about taking the job at Hanover so that I could live someplace like Madison but the truth is, I just got lucky. If you haven’t visited Madison, start making plans now. And assume that once you visit, you might not want to leave. It happens to a lot of people.

One of my favorite places in Madison is the coffee shop. There’s been a coffee shop in this location for as long as I’ve been in Madison—about 15 years. The current incarnation is The Red Roaster Coffee and Eatery. I wrote this speech in the coffee shop; it’s where I get most of my best work done. If you come to Madison, you’ll probably find me there.

Here’s what you might see on a typical day in the coffee shop. Nick and Rich, who both work there, might make a bet about whether I’ll order an iced tea or a cappuccino that day. They know what their regulars like and sometimes they’ll make your drink for you before you even order. Folks will come in and gossip with Rich, who’s the manager. In good places, you’ll hear lots of gossip, lots of people talking, because that’s part of what good places do. They foster interaction and gossip is a kind of social interaction that makes up the fabric of community; it’s sharing knowledge and creating community. The coffee shop would be a great place to study gossip. You’d think people would lower their voices, but they really don’t, so you can imagine all the interesting things you might hear sitting there.

At the coffee shop, you can sit on a nice stool looking out the window onto Main Street. You’re looking at a walkshed. People walk the streets of Madison at all hours of the day and night. They walk to parks and our movie theater and to see music or shop or go to the library. You’ll see seniors walking by, with their walkers. They might be going to the senior center down the street. They come into the coffee shop and strike up conversations. Bill is a regular who’s elderly and developmentally disabled and sometimes he’ll be taking a little snooze in one of the comfy chairs in the corner.

You’ll also see young people. This is a picture of my daughter and her friends. She’s been doing her homework in the coffee shop since kindergarten and she’s a sophomore in high school now. This was her corner store as she grew up. She still comes here with her friends. There are college students from Hanover and Ivy Tech, too. The coffee shop, like all good places, draws a diverse group of people. It’s a home for the funky kids, the ones who might not fit into other spaces in a small, rural town. But you’ll also see middle-aged women who get together to knit or color in adult coloring books. You’ll see members of our LGBT community and people of color. Different races, different class backgrounds, different ages, different political beliefs. I believe for some people who come into Madison Coffee and Tea Company, it may be the only conversations they have all day long.

At the coffee shop, people have repeated spontaneous contact. We met our friend Dave at the coffee shop. He lives across the street from us, but we’d never met him. We didn’t meet him because my partner and I have jobs and a child who needs to be places. But we walk to the coffee shop and that’s where we met Dave.

Every day I’m thankful to live in a town like Madison with places like the coffee shop. I know what it is to lose places. And I know that many people aren’t so lucky.

Making better places

We can no longer afford to take the places we live for granted. They’re too important. I’ve only touched the surface of what we’re learning about how places matter.

As we move forward, we must make sure that the places we make our inclusive for all people. The elderly, young people, funky people, LGBT people, poor people and people of color. Ashley Ford is a writer who grew up in Indiana and now lives in New York. She’s African-American and she recently tweeted about her desire for small-town life, but the obstacles she faces as a black person. Racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and classism are everywhere, even in places like New York City. But all places, big and small, must commit to combatting those hatreds in our communities. We can’t consider the places we make and preserve successful unless they are open and welcoming to everyone.

Here is what I want to tell you as a sociologist who studies place. You are all in the business of shaping and molding places. Of preserving them and making them vital and sustainable and welcoming and open. People may say that this is a low priority, but I hope I’ve shown you how crucial places are. A place can make the process of full of health and happiness or full of loneliness and sickness. A place can be a fertile ground for the growth of lasting and meaningful friendships. Places can leave us lonely and without connection and more likely to turn to addiction.

When we lose a place like the corner store, we have lost more than just a building. Don’t allow anyone to convince you otherwise. We need to fill the world with placists, with people who are unapologetically committed to the importance of place. There’s so much at stake and it’s not an easy task. The lure of the parking lot is always where. But I can’t imagine a more important job or a more important calling.

April 16, 2017

National Poetry Month: Day 16

For Day 16, an anagrammatic poem about our cat, Kevin.

Kevin

Keep her, as in what my husband knew I would say if he pointed out the kitten on our back porch, small and black with ears too big for her head.

Every day I tell her the things I would like to say to myself—“You’re beautiful and everyone loves you.”

Violent, sometimes. Even a cat as large as her can only carry the burden of so much love and need.

In the hardest moment, the forging together of something that would be a family, she came to us and waited for us to let her inside.

Named by our daughter, she is not so much ours as we are hers, a lesson she brought with her from the very first day.

April 15, 2017

National Poetry Month: Day 15

Thom Brennaman and Chris Welch, the Reds TV announcers, are no Vin Scully. But even these two can’t quite ruin the poetry in the language of a game being called.

Silky smooth

You’ve gotta love that.

That’s a double with style.

He had 1 and 11 last year.

And the Reds have the go-away run.

At third with Jose Peraza

Let’s check in downstairs

You can hit

Or bunt

It’s your choice

Get ‘em on

Get ‘em over

Get ‘em in

In a big situation right here

Nowhere near the strike zone

The go-ahead run

Has to duck underneath that line drive

I’d be thrilled to do that again

You know what I mean?

Oh, youth.

I’ll tell you one thing right now, though.

This is not going to get the run in.

Igelesias doesn’t run, he glides

I mean, just silky smooth.

April 14, 2017

National Poetry Month: Day 14

Emily Dickinson

A Light exists in Spring

Not present on the Year

At any other period –

When March is scarcely here

A Color stands abroad

On Solitary Fields

That Science cannot overtake

But Human Nature feels.

It waits upon the Lawn,

It shows the furthest Tree

Upon the furthest Slope you know

It almost speaks to you.

Then as Horizons step

Or Noons report away

Without the Formula of sound

It passes and we stay –

A quality of loss

Affecting our Content

As Trade had suddenly encroached

Upon a Sacrament.

April 13, 2017

National Poetry Month: Day 13

by Michael Shepherd

This is an angry poem.

About those weasel phrases

which blow like paper in the street

going nowhere,

hiding truth,

helping us to

deceive ourselves.

‘The pee-yus pro-sayus’ –

say it in the Irish voice

of obscurantist politicians

often enough

and we’ll accept it as a term,

and believe that it needs hard work

and forward planning

and careful progress

and compromise

and agreements

and initiatives

and ‘generous’ concessions

and declarations of intention

and cautious examination

of opponents’ motives

in the ‘battle’ for peace

and coming together

to establish differences…

Peace

is what is eternally there

when war and strife is absent.

Eternally.

I can’t remember Christ

(was he Catholic or Protestant? I just can’t remember…)

saying

‘Peace process be unto you’…

uh, when would that be? …

or commanding the waves of the Sea of Galilee

‘Engage in the peace process – be still’…

somehow it just doesn’t seem to carry weight

as a blessing or a do-it-now…

‘Go in process towards peace, my child…’

I wonder why that is.