Robyn Ryle's Blog, page 15

October 18, 2012

Doing nothing on Taylorsville Lake

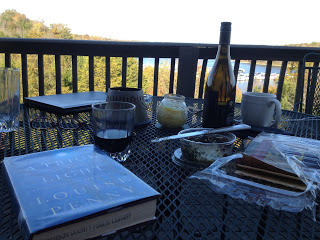

A picture of doing nothing

One of the hardest things in life is to do nothing. In today’s society, it is an act of defiance, a bold declaration liable to earn you one of the worse labels any American could be saddled with–lazy. Once upon a time we were perhaps good at doing nothing, but it is a skill that even in this age when actual employment is hard to come by, is rarely looked at favorably. To do nothing is to swim upstream and risk being clubbed over the head for your efforts.

This is true of Americans even when we vacation. Vacations are supposed to be a rest from all the doing, and yet most of us just go right on about our business, discovering what there is to do in the new place and spending our precious “free” time consumed with activities. Think about the travel brochures for resorts, hotels and parks which provide a helpful list of “Things to Do.”

This fall break, my husband and I got as close to perfecting the doing of nothing as might be possible in a two day period.

Sunrise over the lake

We did nothing at Edgewater Resort on Taylorsville Lake, in Taylorsville, Kentucky. This man-made lake was created by the Army Corps of Engineer in 1974, so as man-made lakes go, it’s not very old. This may explain why I’d never heard of Taylorsville Lake until this two-night deal came across my e-mail inbox courtesy of Living Social. The lake is only about 30 minutes from downtown Louisville, and surrounded by Taylorsville Lake State Park. You could drive within a mile of this lake through the Kentucky landscape, and if you weren’t looking for it, you’d have no idea it was there.

Our cottage at Edgewater Resort looked over the state park marina, and so we could sit out on the back deck and watch boats putting into the water and being pulled back out. The sound carried up the side of the hill in a way that made conversations perfectly audible from our back deck, one of the mysteries of growing up in a land of hills and valleys which I’ve always loved. Listening to the sounds of boats being lowered into the water and the conversations of people at the marina was about the only interruption in our complete and total doing of nothing.

So, okay, in the interest of complete honesty, there was some eating. We loaded up on food at the Whole Foods in Louisville before we headed down to Taylorsville on Monday evening. And we did open a bottle or two of wine. There was the strain of lifting the cover off the hot tub sitting on the back deck of all the cottages at Edgewater Resort. And I will admit that I read almost two whole books (yes, two more in the Chief Inspector Gamache series about which I will not shut up).

But beyond those mild exertions, we sat on the back deck. We watched boats come and go. We noticed the way the light changed over the surface of water. We waited for the stars to come out. We noticed the sound of the wind blowing through the trees. We did nothing.

It was hard at times. Hard to ignore the informational brochures with their lists of local attractions which the nice woman provided us when we checked in. Hard to suppress the urge to go for a hike or get a massage or check out the Mexican restaurant we passed along the road. Hard to ignore e-mails and the looming tasks that lay beyond those two days. But we persisted. We stuck with it.

We did nothing.

Published on October 18, 2012 12:56

October 15, 2012

Madison Monday: the tour of trees

There was a lot going on this weekend in Madison. Many of the folks you might have seen wandering around the streets were checking out the Tri Kappa Tour of Homes, a chance to peek inside some of the amazing homes around Jefferson County. On Saturday, Main St. closed down for Soup, Stew, Chili and Brew, the best soup by far in my humble opinion being the Indian cauliflower stew at the RiverRoots booth. Up at the college we saw the debut of the historical drama, When Jenny Lind Came to Town, based on the visit of this famous 19th century singer along with P.T. Barnum to Madison in 1851.

All wonderful fall events, and the weather on Friday and Saturday was perfect. The highs were in the 70s and the sun was shining. On Sunday, things got a little cloudy, a little windy, a little rainy, and that's when I decided to go out for a walk and experience one of my own favorite fall events in Madison, the turning of the leaves.

I have a friend who moved to back to the Midwest from California this year, and she was asking back in September how the leaves would be this year. A dry summer often presages some lackluster fall foliage, and this was one of the driest summers on record in Indiana. Sitting at the bar at the 605, a crowd of locals assured her that the leaves would be nothing to see this fall. They would all turn an ugly brown. They would fall off en masse before they ever turned. Prepare to be disappointed.

Well, perhaps this is not the most spectacular year for fall foliage, but just maybe that little streak of rain back in September saved us from complete disaster. The trees in downtown Madison, at least, are still putting on a show.

I'm never sure if fall colors look best on sunny days or cloudy days. Certainly, the bright sunshine allows the reds and yellows and oranges to shine. But to me there's something especially striking about the way a turning tree looks framed against a gray and cloudy sky. With a very bright tree, it's as if its leaves are their own source of light in the gloom. My walk on Sunday allowed for both--trees in the clouds, trees in the sun, trees in the rain.

Of course there are the trees that line either side of the river valley down here in Madison, and those are the kinds of views for which many people travel to places like Vermont. But there's something to be said about the tree in town, framed against a beautiful old building or a landscaped bush. These are the trees that put on their shows right outside our doors and windows, who drop their gorgeous leaves on the sidewalks at our feet, creating a carpet of art for us to walk on. They're the trees that peak out in the distance like something on fire. They're the old familiar trees, that given just the smallest bit of encouragement, faithfully put on a show for us every year.

For more images from my fall walk downtown, checkout You Think Too Much on Facebook, here.

All wonderful fall events, and the weather on Friday and Saturday was perfect. The highs were in the 70s and the sun was shining. On Sunday, things got a little cloudy, a little windy, a little rainy, and that's when I decided to go out for a walk and experience one of my own favorite fall events in Madison, the turning of the leaves.

I have a friend who moved to back to the Midwest from California this year, and she was asking back in September how the leaves would be this year. A dry summer often presages some lackluster fall foliage, and this was one of the driest summers on record in Indiana. Sitting at the bar at the 605, a crowd of locals assured her that the leaves would be nothing to see this fall. They would all turn an ugly brown. They would fall off en masse before they ever turned. Prepare to be disappointed.

Well, perhaps this is not the most spectacular year for fall foliage, but just maybe that little streak of rain back in September saved us from complete disaster. The trees in downtown Madison, at least, are still putting on a show.

I'm never sure if fall colors look best on sunny days or cloudy days. Certainly, the bright sunshine allows the reds and yellows and oranges to shine. But to me there's something especially striking about the way a turning tree looks framed against a gray and cloudy sky. With a very bright tree, it's as if its leaves are their own source of light in the gloom. My walk on Sunday allowed for both--trees in the clouds, trees in the sun, trees in the rain.

Of course there are the trees that line either side of the river valley down here in Madison, and those are the kinds of views for which many people travel to places like Vermont. But there's something to be said about the tree in town, framed against a beautiful old building or a landscaped bush. These are the trees that put on their shows right outside our doors and windows, who drop their gorgeous leaves on the sidewalks at our feet, creating a carpet of art for us to walk on. They're the trees that peak out in the distance like something on fire. They're the old familiar trees, that given just the smallest bit of encouragement, faithfully put on a show for us every year.

For more images from my fall walk downtown, checkout You Think Too Much on Facebook, here.

Published on October 15, 2012 06:44

October 12, 2012

Place in Fiction: Where are we, anyway?

As you may have been able to tell, lately my reading has been confined almost exclusively to mystery novels by Louise Penny featuring her detective, Chief Inspector Armand Gamache, and the familiar residents of Three Pines, a fictional village just south of Montreal. At the same time, I’ve been working on yet another edit of the novel that I started writing myself last summer. I have 82,000 words of a largely coherent story which my incredibly kind and supportive husband claims is quite “polished.” My novel is also set in a “fictional” place that is really not so fictional at all, and it’s gotten me thinking about the nature of place in fiction and the nature of the fictional place.

I feel certain that whole dissertations have been written on this topic. Or if they haven’t, they certainly should be. But I’m too lazy to find them and read them, so instead I’ll ramble on about it myself, at great length. I started writing one post on this topic, and realized I had entirely too much to say. So in Part 1, I’m considering the difference between real places and made up places.

Why, I find myself wondering, do authors invent fictional places that aren’t really that fictional? Yoknapatawpha County is based on Lafayette County, Mississippi. Port William, the “fictional” town where Wendell Berry’s novels takes place, is really Port Royal, Kentucky, a town just down the river from Madison. Louise Penny really lives outside a small village south of Montreal, which must form the basis for Three Pines. Why not just write about Lafayette County or Port Royal? Why make up a place that is both real and not real?

The simplest answer is that real places have certain limitations that made-up places don’t. If you want there to be a grocery store that’s closing down in your town, but there isn’t a grocery store that’s closing down in the actual town in which you’ve set your story, you’re in trouble. Sure you could plop a failing grocery store down somewhere, but then you’ve already begun the process of fictionalizing a real place. How far do you take that process before the place you’re writing about has moved so far away from the real place as to become unrecognizable?

This brings up the whole question as to whether you are always fictionalizing a place when you sit down to write about it. I have read stories set in places I know fairly intimately and found them unrecognizable. “That’s not the place I knew,” I think. And of course, it is not, because the place I knew is fairly unique to me and my own perspective.

As a sociologist, I’d go so far as to ask whether we aren’t all living in fictional places all of the time. One of my advisees is taking a course called Self and Social Interaction which focuses quite heavily on the social construction of reality. In my office the other day, he explained to me that when he was little, he imagined that he was living in an imaginary world he’d made up, and that everything in it was just the product of his own imagination. After taking this class and reading some of the theorists, he had come to the conclusion that in many ways, that childhood fantasy was actually the truth. We experience everything around us through our own unique filter made up of our memories, our biases, our knowledge (or lack of it), our values and our own actual sense organs, which are flawed instruments, to say the least. So the world I'm living in actually is unique to me.

Small differences you might easily dismiss. I have an astigmatism in one eye and I’m near-sighted, so when I look at objects at a distance, they look very differently than they do to someone with perfect vision. But culture also impacts how you perceive the place in which you live. The Basa people of Liberia have only two colors: ziza, which encompasses everything that we would call purple, green or blue; and hui which includes red, orange and yellow. In the world I’m living in, I’m sitting on a red couch writing this. I experience the couch as red with all the particular meanings that has for me. But if a Basa person were sitting on my couch, they’d be sitting on a hui couch. And though my yellow mug would be a different color to me, to the Basa, it would be the same color as the couch. We are living in two different worlds.

When you sit down to tell a story about a place, you are describing the reality of that particular place as you experience it, which may be very different from how someone else experiences it. My own particular experiences of living in Madison and the stories I tell about it are not the same as my neighbor’s. Which is the real Madison?

When I walk around Madison every day, then, the Madison I am walking around is not exactly the same Madison in which my husband strolls about. When I start to tell a story about Madison, I’ll be telling a story about my Madison, and mostly not my husband’s Madison. But in the story-telling, I will get either much farther away from the “real” Madison, or much closer to it, or a little bit of both, depending on your own particular perspective.

You could begin right now, at this very moment, to describe the place in which you live, and even if you went at it for the rest of your lifetime, you would never achieve a complete and totally accurate description. Let’s start with my house. I could say it’s a green, brick, Madison double. And then I could add that it has a front porch. The front porch is painted black, but the paint is peeling. And I could just say that the paint is peeling, but you wouldn’t know exactly how and where the paint is peeling, and getting all that down would take a couple of days. And then I’ve told you it’s green, but I haven’t told you exactly what color green it is. And if we’re honest, it’s not exactly the same green everywhere. So that might take about a week. And so far I haven’t even gotten to the inside of the house at all. And in those two weeks I’ve spent describing the porch and the color of the house, both of those things have already changed.

All stories are partial. We pick and choose what we tell. I will describe the inside of the restaurant, but not the items on the menu. I will tell you about the car accident I had, but not how fast I was going when it happened. I’ll include the fact that it was raining, but not bother with the detail that it was a light drizzle as opposed to a downpour. If the stories we tell are partial, then they are farther away from the truth, right? Because I leave things out when I describe Madison, my version is even less real.

Or perhaps my version is actually more real. Emily Dickinson wrote, “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant–/Success in Circuit lies.” When we turn “reality” into a story, are we making it more or less true? What exactly is the truth we’re telling? Is truth conveyed in a perfect mirror image of Madison, knowing already that it could only be a mirror image of the Madison I experience, as opposed to the Madison experienced by someone else? Or is truth conveyed in what Dickinson calls the “slant”, the “circuit”?

Have you ever read a story or a novel and thought to yourself, “Yes, that is exactly how that feels.” Or, “Yes, that is exactly how that is.” It is the truth. But it’s not. Someone made it up. And yet it is still the truth. It is a different kind of truth. A truth that is made-up, but real. A larger truth about what it means to lose, to win, to love, to grieve, to laugh, to cry. A truth about what it means to live. That is the other kind of truth which stories might, in fact, be best equipped to tell.

So why make up a fictional place to tell your story? In part because all places are somewhat made up anyway. But also perhaps because a made-up place is a better way to get at the particular kind of truth which stories are meant to tell.

Stay tuned next time when I explore the god-like giddiness of making up your own town or city or country in a story.

I feel certain that whole dissertations have been written on this topic. Or if they haven’t, they certainly should be. But I’m too lazy to find them and read them, so instead I’ll ramble on about it myself, at great length. I started writing one post on this topic, and realized I had entirely too much to say. So in Part 1, I’m considering the difference between real places and made up places.

Why, I find myself wondering, do authors invent fictional places that aren’t really that fictional? Yoknapatawpha County is based on Lafayette County, Mississippi. Port William, the “fictional” town where Wendell Berry’s novels takes place, is really Port Royal, Kentucky, a town just down the river from Madison. Louise Penny really lives outside a small village south of Montreal, which must form the basis for Three Pines. Why not just write about Lafayette County or Port Royal? Why make up a place that is both real and not real?

The simplest answer is that real places have certain limitations that made-up places don’t. If you want there to be a grocery store that’s closing down in your town, but there isn’t a grocery store that’s closing down in the actual town in which you’ve set your story, you’re in trouble. Sure you could plop a failing grocery store down somewhere, but then you’ve already begun the process of fictionalizing a real place. How far do you take that process before the place you’re writing about has moved so far away from the real place as to become unrecognizable?

This brings up the whole question as to whether you are always fictionalizing a place when you sit down to write about it. I have read stories set in places I know fairly intimately and found them unrecognizable. “That’s not the place I knew,” I think. And of course, it is not, because the place I knew is fairly unique to me and my own perspective.

As a sociologist, I’d go so far as to ask whether we aren’t all living in fictional places all of the time. One of my advisees is taking a course called Self and Social Interaction which focuses quite heavily on the social construction of reality. In my office the other day, he explained to me that when he was little, he imagined that he was living in an imaginary world he’d made up, and that everything in it was just the product of his own imagination. After taking this class and reading some of the theorists, he had come to the conclusion that in many ways, that childhood fantasy was actually the truth. We experience everything around us through our own unique filter made up of our memories, our biases, our knowledge (or lack of it), our values and our own actual sense organs, which are flawed instruments, to say the least. So the world I'm living in actually is unique to me.

Small differences you might easily dismiss. I have an astigmatism in one eye and I’m near-sighted, so when I look at objects at a distance, they look very differently than they do to someone with perfect vision. But culture also impacts how you perceive the place in which you live. The Basa people of Liberia have only two colors: ziza, which encompasses everything that we would call purple, green or blue; and hui which includes red, orange and yellow. In the world I’m living in, I’m sitting on a red couch writing this. I experience the couch as red with all the particular meanings that has for me. But if a Basa person were sitting on my couch, they’d be sitting on a hui couch. And though my yellow mug would be a different color to me, to the Basa, it would be the same color as the couch. We are living in two different worlds.

When you sit down to tell a story about a place, you are describing the reality of that particular place as you experience it, which may be very different from how someone else experiences it. My own particular experiences of living in Madison and the stories I tell about it are not the same as my neighbor’s. Which is the real Madison?

When I walk around Madison every day, then, the Madison I am walking around is not exactly the same Madison in which my husband strolls about. When I start to tell a story about Madison, I’ll be telling a story about my Madison, and mostly not my husband’s Madison. But in the story-telling, I will get either much farther away from the “real” Madison, or much closer to it, or a little bit of both, depending on your own particular perspective.

You could begin right now, at this very moment, to describe the place in which you live, and even if you went at it for the rest of your lifetime, you would never achieve a complete and totally accurate description. Let’s start with my house. I could say it’s a green, brick, Madison double. And then I could add that it has a front porch. The front porch is painted black, but the paint is peeling. And I could just say that the paint is peeling, but you wouldn’t know exactly how and where the paint is peeling, and getting all that down would take a couple of days. And then I’ve told you it’s green, but I haven’t told you exactly what color green it is. And if we’re honest, it’s not exactly the same green everywhere. So that might take about a week. And so far I haven’t even gotten to the inside of the house at all. And in those two weeks I’ve spent describing the porch and the color of the house, both of those things have already changed.

All stories are partial. We pick and choose what we tell. I will describe the inside of the restaurant, but not the items on the menu. I will tell you about the car accident I had, but not how fast I was going when it happened. I’ll include the fact that it was raining, but not bother with the detail that it was a light drizzle as opposed to a downpour. If the stories we tell are partial, then they are farther away from the truth, right? Because I leave things out when I describe Madison, my version is even less real.

Or perhaps my version is actually more real. Emily Dickinson wrote, “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant–/Success in Circuit lies.” When we turn “reality” into a story, are we making it more or less true? What exactly is the truth we’re telling? Is truth conveyed in a perfect mirror image of Madison, knowing already that it could only be a mirror image of the Madison I experience, as opposed to the Madison experienced by someone else? Or is truth conveyed in what Dickinson calls the “slant”, the “circuit”?

Have you ever read a story or a novel and thought to yourself, “Yes, that is exactly how that feels.” Or, “Yes, that is exactly how that is.” It is the truth. But it’s not. Someone made it up. And yet it is still the truth. It is a different kind of truth. A truth that is made-up, but real. A larger truth about what it means to lose, to win, to love, to grieve, to laugh, to cry. A truth about what it means to live. That is the other kind of truth which stories might, in fact, be best equipped to tell.

So why make up a fictional place to tell your story? In part because all places are somewhat made up anyway. But also perhaps because a made-up place is a better way to get at the particular kind of truth which stories are meant to tell.

Stay tuned next time when I explore the god-like giddiness of making up your own town or city or country in a story.

Published on October 12, 2012 08:32

October 8, 2012

Madison Monday: A weekend without internet

I’m writing this installment of Madison Monday in the face of glaring uncertainty as to whether I’ll actually be able post it on my blog. It might be, as one of my friends suggested, a sign of the coming apocalypse, but this weekend, there was no internet in Madison. Chaos ensued.

Okay, that’s probably a slight exaggeration on several fronts. I’m sure lots of people in Madison had access to the internet this weekend. But many folks using Cinergy Metronet as their provider were without service for varying periods of time. The rumor was that someone hit a pole somewhere, and this stretched the fiber optics, leading to widespread outages.

I couldn’t actually confirm this rumor because, you know, I couldn’t get on the internet. But when I called the service line for Cinergy Metronet on Saturday, I was put on hold, and duly informed that there were 536 customers ahead of me on hold. And then I hung up.

As to the chaos, my husband and I were greeted by an almost empty Shooter’s on Saturday afternoon and a sign on the door which read, “Cash and local check only.” With the service outages, none of their credit card machines nor their computerized ordering system was working. They lugged out the old cash register and went about business. Thankfully, we had cash and didn’t have to go without our Saturday afternoon beer. But you can certainly see the potential for chaos there, can’t you?

And, yes, technically, because I have an iPhone, I was not completely deprived of access to the internet. It was on Facebook, in fact, that I heard the rumor about the downed pole and saw that at least one other restaurant was also unable to accept credit cards for a while.

Thankfully, we did get in touch with Metronet on Sunday and discovered that though our wireless router was not working, we did have Internet through an ethernet cable. My husband watched the Eagles game on our computer sitting at the dining room table, which is where our router is located, which was a mixed blessing, as the Eagles lost. And this Monday morning, a very nice man showed up from Metronet to replace our wireless router and get us back in business.

But there were things I needed to do this weekend that did not get done, all the same. Important things that could not be handled on an iPhone. I can’t remember precisely what they were, but it seemed at the time that they could really only be done with a functioning internet. And in the absence of my window on the world, I was forced to do things like write this post. And bake some bread. Play my guitar. Do some laundry. Clean the upstairs bathroom. As you can see, it was quite a hardship. If this happens again, I might actually be forced to go outside.

Published on October 08, 2012 06:45

October 4, 2012

What to wear: reflections on clothing and identity

If you could dress in a way that perfectly reflected who you are on the inside, what would you wear?

This is a question that’s been on my mind lately. In one of my classes, we’re talking about school dress codes, and how they reflect certain cultural values about what is and isn’t appropriate bodily presentation. As one student described, most school uniforms make her think of England, and ethnically, they reflect a WASP identity imported to the United States from British boarding schools. Another described them as white-collar or reflecting the social class of the rich and wealthy. And school uniforms are often gender specific–girls wear skirts and boys wear pants–reflecting a set of gender beliefs as well. Uniforms specify which body parts must be covered, supporting a status quo in regards to sexuality, as well. In other words, school uniforms impose certain norms about ethnic, social class, gender and sexual identities onto students.

And yet, as one of my students pointed out, if you don’t learn how to dress in a way to conform to those norms, you’re probably going to be at a disadvantage in the world. When someone tells you to “dress for success,” they have a very certain style of dress in mind, a style that excludes a whole range of possible cultural self-expressions. There are no school uniforms that consist of baggy pants and wife-beater tank tops or short-shorts for all the boys and neckties for all the girls.

Me and my fedora

This morning I saw one of my colleagues walking to class. In the early morning light on campus, it looked as if this lone figure might have very well walked straight out of the 1950s. Not the 1950s of Mad Men, particularly. His style is a little bit more academic than what Don Draper is likely to wear. But it was complete with a fedora, and even a certain way of moving that spoke of a whole other century.

He looked good, I have to admit, but I couldn’t help but wonder, why? Why would you so meticulously mirror the dress style of a historical period of which you have no actual experience, as this colleague was not alive during the 1950s? Does your fedora express something about who you are on the inside? Does it just feel right in a way that nothing from this century quite does? If you could dress in a way that perfectly reflected who you are, would it include a fedora?

This Monday was a banner day for my own personal couture. I was sporting a new shirt purchased at Chautauqua over the weekend--a tight-fitting, navy blue t-shirt with a screen print design of a tree. This with a long, off-white skirt, my wine-colored Dansko shoes, and a gauzy green wrap purchased in Baltimore. It was a good hair day, too, and I felt, in an especially magnified way, “put together.” I felt competent and professional and smart and suave. And maybe a little bit sexy, as well. It was very hard not to wear the same outfit again the next day, so amazing did I feel in it. So was that my very own, best outfit? Was that particular combination of clothes the most perfect reflection of my internal sense of who I am?

Turning it inside-out

But I’m a sociologist, so I understand that the internal is the external. And here’s where things get complicated. I want to ask what you would wear to reflect your internal sense of yourself in a world free from all the cultural influences that inevitably shape the things we wear. But no such world exists. It’s no coincidence that my colleague’s sense of style perfectly reflects 1950s, American academia; it’s part of the cultural repertoire of clothing that’s available to him. And I can certainly make no claim to having arrived at my perfect outfit in a cultural void. The outfit felt so right to me largely because of my sense that it lined up in a manner comfortable for me with the particular set of prescribed norms about what is and isn’t fashionable in my particular corner of the world at this particular moment in time. It felt good to me because there was almost a satisfying little click between my clothing choices and what I believe my culture tells me looks good for a professional woman in her late 30s. For those few moments, I felt that I was dancing in sync with the zeitgeist. What does that reflect about my own personal sense of who I am, except that I’m something of a sheep, feeling deeply satisfied in my own slavishness to fashion?

Me in a salwar kameez

When I was in India, I fell in love with salwar kameez. These beautiful outfits are common in Southeast and Central Asia. In India, women wear them in a cacophony of colors and patterns and styles. The particular versions of salwar kameez I purchased have pants so baggy and light that it feels as if you’re not wearing pants at all. The tunic is long, and drapes down over the pants almost to your knees. And then there’s a long, gauzy, matching scarf, which is most often worn draped around your neck, with the loose ends trailing down your back.

A salwar kameez is not a dress, and yet it is one of the most feminine things I feel I have ever worn. There was something about the flowing material of the scarf or about the freedom of the pants billowing out. None of my particular version of the outfit is form-fitting, and yet it felt sexy to wear a salwar kameez. Salwar kameez were as foreign to my own cultural background as you could possibly get, and yet for those two weeks in India, nothing ever felt so comfortable and right. And when I wore the salwar kameez, I was, in fact, different. Wearing those clothes changed how I felt. Wearing the salwar kameez changed who I was.

The tyranny of the pantsuit

“Dress lazy, act lazy. Dress dirty, act dirty,” one of my students quoted at me in our discussion of school dress codes. “The clothes make the man.” But what would you wear?

Hillary sporting the pant suit

The worst thing I ever had to wear were the series of professional pant-suits and skit-suits I purchased for my first go-around on the academic job market. I disposed of these outfits as soon as I felt relatively safe in my job. Over the years have gone along with them any other items of clothing that had once seemed to be necessary to the life of a professional woman, but had never really felt right. I did not feel powerful or competent or intelligent or competent in these suits. I felt like someone in a Halloween costume. I was dressed up for the part, but it said nothing about who I was. I gave the job talk, did the interviews, got the job. And when I have to do something more formally professional now than teaching my students, I wear what feels right to me, because that’s more important than anyone else’s sense of what I should wear.

So I am not just a slave to what society tells me I should wear, after all. There are limits. There are places I won’t go. There are shoes I won’t buy. There are people I won’t become.

Playing dress up

The same sweater that made up part of my perfect outfit on one day felt like the garment of a frumpy old woman on a different day. One day last week, I was walking down the hallway in my sweater, and a glimpse of myself in frumpy clothes flashed through my head, like one of those old non-descript women who are always being described in British mystery novels. It was an image that made me smile, and want to go out and buy a very dull and shapeless tweed skirt. I thought it would be nice to play at being that woman, at wearing those clothes.

For one Halloween, I dressed up as a dominatrix, complete with a bustier, dog caller, and whip. For that night, I felt like I had been living my whole life as Clark Kent, and then suddenly, I became Superman. I became someone else. Someone very different from the person I normally was, but not really someone who wasn’t there all along, waiting for the opportunity to come out and play.

So am I a frumpy old woman inside, or a dominatrix?

The naked and the dead

If you could dress in a way that perfectly reflected who you are on the inside, what would you wear? Would you just go naked? Is your naked body the truest reflection of who you are, the outfit you wore into this world, but not the outfit you’ll wear when you’re leaving it. We clothe the dead, and those clothes matter. They are carefully selected, sometimes by the living and sometimes by the dead. Is it the clothes we wear into the grave that best reflect who we were in life? But what if someone puts me in a pantsuit?

Perhaps there is no one outfit. Perhaps there isn’t even any one coherent style. There are the atrocities you wore in your early teens. The period in college where you experimented with men’s clothes. The month you spent wearing the exact same white t-shirt day after day. The long years of your life where you felt it was completely unacceptable and vaguely oppressive to show cleavage. And then the realization that maybe there was a little less at stake where your boobs were concerned.

There are the days when you want to be a frumpy, English woman and the days when you feel you have reached the perfect moment in the development of your own personal sense of style. And then you start all over again. And every day is Halloween. We dress up every day. We put on costumes. We try out what this shirt says about us and how it makes us feel. We do so within constraints, but then sometimes, we find spaces of freedom where we can get closer to wearing exactly what we want. And what we want to wear is quite complex and always changing. Sometimes it includes a fedora.

If you could dress in a way that perfectly reflected who you are on the inside, what would you wear? Everything. Except a pantsuit.

Published on October 04, 2012 10:14

October 1, 2012

Madison Monday: Chautauqua and holidays Madison-style

It’s Monday in Madison, and on cue the beautiful weather that held out all weekend is gone. That’s just fine with me, because really, Monday’s should be kind of overcast with the potential for rain. Otherwise, we’d all feel deeply resentful about the fact that we can’t just go on wandering around the streets of Madison, looking at art, listening to music, and eating festival food.

Another beautiful Chautauqua weekend is officially in the books with very little incident. I’m sad to say that my Madison Rules were not always obeyed...I saw several folks crossing in the middle of the street rather than at the crosswalk, though they might be excused by the complete logjam of cars that was Main St. on Saturday afternoon. We did almost get run over by a car trying to turn right and not yielding to pedestrians. I also had to explain to my parents, who came up to visit, that though you can use the lawn chairs to save a parking space, you cannot just put lawn chairs anywhere willy-nilly. It’s really only appropriate to place them directly in front of your house, particularly in the spot that you and all your neighbors generally recognize as “your spot.” This would be the spot that if you come home and find someone who is not you parked there, you’re liable to say, “Who took my spot?” And if your neighbor, due to the cascade effect caused by someone taking their spot, parks in your spot, they’re liable to say, “Sorry I had to take your spot.” Next year I’ll have to be more clear.

The most creative parking-spot-saver I saw this weekend was a loan planter sitting along the curb on 3rd St., complete with a rather sad-looking geranium still inside. This was late on Sunday afternoon, when most folks were leaving town, so I can’t attest to how effective this lone planter was at saving a parking spot. I couldn’t help but see it as an act of parking space desperation.

Thinking about Madison compared to other small towns (real and imaginary), I’ve increasingly realized that though we certainly celebrate the big holidays–Christmas, Halloween, Easter–we’re lucky enough to have an additional set of holidays all our own. I’m declaring Chautauqua one of them. Also on the list would be folk festival (RiverRoots) in the spring. And the upcoming Soup, Stew, Chili and Brew. And of course, Regatta. You know an event is approaching holiday status when you’re moved to greet people with a, “Happy Chautauqua!” which is exactly how I felt this weekend.

The beauty of having a unique set of holidays is that there’s much less of the generalized anxiety often associated with the holidays we share with the rest of the world. If your family doesn’t live in Madison, they don’t really expect you to spend Chautauqua with them, so there’s none of the guilt and schedule conflicts that come along with Thanksgiving or Christmas. Also, there’s fried cheese, which is sadly lacking from traditional, non-Madison holidays.

So, let me wish everyone a belated Happy Chautauqua, and an early Happy Soup, Stoup, Chili and Brew, coming up in just two weeks.

For many more great pictures and videos from this weekend's Chautauqua, check out inMadisonIN.com.

Published on October 01, 2012 07:45

September 24, 2012

Madison Monday: Madison Rules

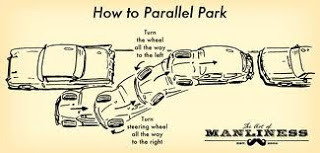

I have no idea what parallel parking has to

do with manliness, but there it is

This upcoming weekend is Chautauqua, a time when a lot of out-of-towners descend on Madison to buy some art, eat some good food, and listen to some lovely music. And just generally to enjoy the pleasures of a September weekend in Madison. Personally, I plan on getting a great deal of my Christmas shopping done this weekend.

With many non-Madisonians on their way, it seemed like a good time to post a set of Madison Rules, the informal norms of social life in downtown Madison. Every community has its own set of unique norms tailored to life in that particular locale, and Madison is no exception.

DISCLAIMER: Of course, in no community is there perfect agreement upon what the rules are. What fun would that be? Most of these are very much my rules, but I understand that there are rules out there that are very much not my rules. I tried to canvas for a general sense of what rules folks would add, but I got no response, so feel free to comment with your own additions.

Rule #1: Learn how to parallel park. Oh, the lost art of parallel parking! What was the hardest part of your driver’s license test? By far, the parallel parking, that insane part of the test which seemed so ridiculously old-fashioned and out-dated. Who parallel parks any more? The answer: downtown Madisonians. All the time. Almost every day. Learn this skill. Become an expert. You won’t regret it.

In various conversations I’ve had with folks about downtown Madison, I’ve often heard the complaint, “There’s not enough parking.” I quickly translate this in my head into, “There aren’t enough parking spaces that I’m actually skilled enough to use.” Parallel parking is a quite efficient and time-tested provider of parking spaces in urban design. There’s plenty of parking in downtown Madison if you learn how to use it.

Rule #2: Know when to open and shut your car door. If you become proficient at the above-mentioned parallel parking, and you do so on Main St., be courteous enough to wait until a break in the oncoming traffic on your side of the street before getting in or out of the driver’s side door.

There is generally enough space on Main St. (though, see Rule #3) for three cars abreast–two traffic lanes and one car parallel parked along the street. There is not really enough room for the parked car to open their passenger-side door and disgorge a person while another car is passing in the right-hand lane. The good news is that traffic on Main St. in Madison is not really ever that heavy, and there are lots of traffic lights to create gaps in the traffic just perfect for getting out of your car without running the risk of being crushed or having your car door rather forcefully removed.

This rule may very well mean that you have to sit in your car or stand outside of your car while you wait for the gap in traffic. Still, this seems preferable to me to the afore-mentioned crushing or loss of your car door, in addition to the difficulties it causes for the people driving down the street, who must either swerve into the left-hand lane to avoid you, or stop in the middle of the street until you are safely in your car and out of the way. If that isn’t incentive enough, think of that pause as a cosmic reminder to slow down...smell the roses...contemplate eternity, or perhaps just why you’re in such a hurry to begin with.

Rule #3: Hug that curb. I once drove around downtown Madison with a friend from out of town who was not used to streets with cars parallel parked along the side. She wasn’t used to judging how close her car was to the parked cars and it made her nervous, so she kept veering out of the right-hand lane and driving in the middle of the two lanes. This made for a rather adventurous ride down Main St., where folks fully expect to use both lanes.

There’s plenty of space on Main St. for three cars, as long as the car that is parallel parked hugs the curb. Exactly what constitutes “too far” from the curb is a delicate thing, but if you live in Madison long enough, you develop an intuitive sense for the proper distance. If you never learn how to parallel park, obviously you will not develop that intuitive sense, so your best bet is to drive around until you can find one of easier parking spaces downtown. Just don’t complain to me about how far you have to walk.

Rule #4: Obey the crosswalks. Okay, so, yes, we are a small town, but even small towns need crosswalks, whose purpose is to tell people when they can and cannot cross the street. We live in a culture where few people walk anywhere anymore, so I feel it’s important to remind everyone exactly what a crosswalk is for. It tells pedestrians–those endangered creatures–when to cross the street. There are quite a few pedestrians in Madison, and so the crosswalks come in quite handy.

Just as a refresher, a red hand on the crosswalk means to stop. Do not cross the street. In Madison, our crosswalks most conveniently count down the amount of time in which you have left to cross the street. Some experience has informed me that to get across Main St., you really need about 10 seconds at least, assuming you’re not running.

If you walk across Main St. when the hand is red, I cannot guarantee that you will not be hit by a car. Actually, I can’t ever guarantee that you won’t be hit by a car. But it’s infinitely more likely if you disobey the crosswalk. And even if you don’t get hit, you will find that you have made some people very angry. Because what are your actions saying? Yes, I see these basic accessories of civilization, designed to balance the needs of competing interest groups (pedestrians and motorists), and I scorn them. I make my own rules. I cross when I want. Your crosswalk be damned! Don’t you think such an attitude merits at least a little nudge from a large, moving vehicle?

Rule #5: Yield to pedestrians. Your car weighs about 4,000 pounds, and at least currently, very few humans compare to that. So just yield, okay? Enough said. Except if they’re disobeying the crosswalk, in which case, you might give them just that little nudge.

Rule #6: Respect the lawn chairs. Okay, this is specifically for out-of-town visitors. Yes, those lawn chairs or garbage cans or flower planters or sawhorses or whatever junk we could find in our garage–they’re sitting along the street next to the curb for a reason. To save our parking space, because, no, Mister, we do not have a garage. Well, okay, actually we do have a garage, but I think you would find it’s quite full of junk and not the easiest thing to get in and out of off a very narrow alley. And anyway, most downtowners do not have garages. We have the space in front of our houses, where we have learned to become excellent parallel parkers, which means we know the exact correct distance apart to set our two lawn chairs in order to reserve our very own parking space. Move these lawn chairs at your own risk.

Is it legal to save a parking space for yourself in such a way? Is it fair? Is it right? Is it ordained by god? I don’t really care. But if you move the lawn chairs in order to park there, I really can’t be responsible for what happens.

Rule #7. Enjoy. Following these simple rules will greatly increase your own enjoyment of our fair town, which, yes, is quite delightful. It will also keep you off the list of those who, all in all, we’d rather not come back. Thankfully, it’s a very short list.

Published on September 24, 2012 14:40

September 18, 2012

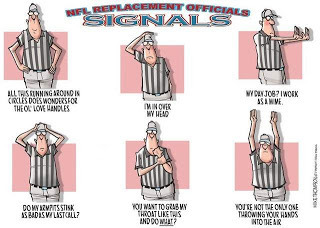

The Sociology of the NFL Replacement Officials

Courtesy of NFL.com

Those of you watching the Monday Night Football game last night between the Denver Broncos and the Atlanta Falcons witnessed first hand the thin line between social order and chaos along which all of us tread on a daily basis. The fragility of the ephemeral ties that hold together any social situation become visible only when things go very wrong, and go very wrong they did last night in Atlanta.

For those of you not mildly obsessed with football, this year the NFL refused to give their referees the money they were asking to be paid. They locked out the regular officials and went with replacements. As Mike Tirico, commentator for ESPN, described last night, the current NFL refs are not like the second string players, who would be a little less spectacular than the first string, but still serviceable. The second string would be the referees for Division I college football, but those guys (and they are guys) are a little busy right now, and uninterested in violating their sense of loyalty to the real NFL referees, anyway. Instead, the NFL had to go after the fourth or firth string guys, referees whose experience includes the Lingerie Football League (which I was deeply disappointed to discover is something that really exists) and Division III college football.

Week One of the season with the replacement referees seemed at least tolerable. Perhaps they weren’t really any worse than the professionals. But in many of the Week Two games, and especially in last night’s Monday Night matchup, a showcase event for the league, you had the sense that somewhere Ed Hochuli and the rest of the regular NFL officials were laughing with glee.

There was much more fighting in last night’s game than usual, a fumble call that took six minutes to resolve, a first quarter that lasted an hour, the image of John Fox (head coach of the Broncos) yelling until he was red-faced at the refs and then waving his hand dismissively at their calls. There were missed calls and calls the replacement officials got wrong, and calls that were overturned by the same official who had made them. But more importantly than that, there was clearly a breakdown in the trust and faith that keep an NFL football game from turning into what it always has the potential to become–twenty-two large, pissed off men beating the crap out of each other.

Social life, as sociologists understand it, is a deeply cooperative endeavor. Almost any social situation is dependent upon the cooperation of all the parties involved, on a tacit agreement on what one sociologist–Erving Goffman–called the definition of the situation. When I sit down in my college classroom, my students and I all agree that we are in a classroom. Based on that definition of the situation, students allow me to get up and talk, while they sit quietly in their chairs and listen. If their definition of the situation were different–say they understood they were at a party instead of in a classroom–chaos would ensue. They would not sit in their chairs, nor would they be quiet, and they certainly would not listen to me explain sociological concepts to them.

In the classroom setting, the students trust that I am who I say I am–a professor with a Ph.D. in sociology–and that I am competent to do my job. They’ve never seen my Ph.D. They weren’t with me in graduate school watching over my shoulder to make sure I learned everything I needed to learn. They walk into the classroom on the first day and take it on faith that I am competent to teach the class. From that point on over the course of the semester, I can lose a little of that faith, I can increase it, or I can maintain it. But if I lose it altogether, bad things will happen, as anyone who’s seen a classroom out of control can tell you.

On an NFL football field, there is even more at stake because of the violence that is inherent in the game. Most of the time, players accept the definition of the situation. They are playing a game of football. The referees are in charge of telling them when a play is over, and they should therefore stop. The referees dictate when it is acceptable to hurl yourself at another human being, and when it is not. The referees say what kind of contact is safe, and what is not. What gives the referees such power over men who by and large could pick them up and pile drive them into the turf without even breaking a sweat?

It’s not the whistles, or at least not only the whistles. What gives NFL officials this power over men who are so clearly physically stronger than them is trust and faith based on their authority. The whistles, the stripes, the flags and the hats are all symbols of the officials’ position of authority over the game. Authority is a kind of power that comes from institutions and in this case that institution is the league itself. The NFL as an institution puts the referees in charge, and most of the time, they are, in fact, in charge.

So what’s happened now? The replacement officials have the stripes, the hats and the whistles. They’ve been put there by the NFL. And for a while, maybe a brief period in Week One, it looked like that was enough.

Cartoon by Mike Thompson,

courtesy of Detroit Free Press

But between Week One and Week Two, something happened. Something changed. The trust and faith that the players and coaches had in the replacement officials eroded. Watching Monday Night’s game, you might conclude that it has altogether disappeared. Part of the definition of the situation shifted, in that both players and coaches no longer seemed to agree that the replacement officials are qualified to tell them when a play is over, when a play is legal, and when a play is too dangerous. The implicit agreement that the referees are generally trustworthy disappeared, and the possibility for what an NFL game always could become was suddenly there for the world to see on their hi-def screens.

The question of whether the replacement officials actually are any worse at making calls than their regular counterparts at this point becomes irrelevant. If no one believes that they are trustworthy–that you can depend upon them to get possession calls in the middle of a pile after a fumbled ball right–then they simply are worse. The Thomas theorem in sociology (perhaps the only theorem that sociology has as a discipline) tells us that what people believe to be real, is real in its consequences. If NFL players and coaches believe that the replacement officials are incompetent, doddering idiots, than the consequences will reflect that reality. Whether they are incompetent, doddering idiots ceases to matter.

And so the result is Monday Night’s game, which in moments looked as if it might devolve to such levels of chaos that everyone would have to throw their hands up in disgust and go home. As sociologists, this is a dramatic lesson in the potential for disorder that always exists beneath the surface of social life. It is a wonderful example of how faith and trust is part of what makes the world function on a daily basis and not just in the NFL. I trust that the food my waitress brings me will not poison me, even though I didn’t observe closely while anyone made it. I trust that everyone else in their cars will also stop when the traffic light is red. I trust that when I put a letter in the mailbox a whole chain of other people I’ve never met will somehow ensure that it gets to the place I intend it to go.

I’m not sure if Roger Goodell, the commissioner of the NFL, has learned this important lesson about social life. If neither coaches nor players have faith in the replacement officials, it’s just a matter of time before something even worse than Monday Night occurs. Players will be injured. Officials will be injured. But more importantly to Mr. Goodell, who after all is the head of the most profitable sports organization in the United States, the quality of his product will decline and his profits will suffer. No one wants to watch a game marred by an endless string of instant replays and reviews, a trend that seemed to be bothersome even before the replacement officials. We all love our football, but we don’t want the first quarter to take an hour to play.

Of course, there are always moments when we distrust the abilities of a certain official, in a certain call, in a certain game. But to feel that the game is no longer in trustworthy hands isn’t really good for anyone, including the fans. And you don’t have to be a sociologist to figure that out.

Published on September 18, 2012 10:32

September 17, 2012

Madison Monday: Three Pines versus Madison

Happening art opening at JoeyG's

I’ve been reading a wonderful mystery series by Louise Penny, the Chief Inspector Armand Gamache series. These books are set in Canada, mostly in a small village south of Montreal called Three Pines. As you will read over and over on the back jacket of the mysteries, “You won’t find Three Pines anywhere on a map, but it’s so real, you’ll want to move there!”

Three Pines is a tiny village tucked into the mountains with a decidedly odd assortment of residents, including a higher than average per capita number of artists, poets and amazing makers of croissant and artisan cheeses. The particular group of residents whom you get to know best so far have regular dinners in which folks just drop by. They celebrate holidays together, they hang out at the local bistro drinking café au lait. They hide Easter eggs for the children in April. They all go carolling in December. Can this place be real?

Madison is a pretty great little town, but no carollers have ever showed up outside my door, though maybe that’s just because I don’t live in the right neighborhood. Reading about Three Pines, I did find myself wishing I lived there. Or at least wishing Madison had some nice croissant (which, to be fair, we did when the 605 would open for breakfast. Alas!)

As I’ve written before, Madison is a real town. We, too, probably have a higher per capita number of artists and poets and other very talented people. But being a real town instead of a fictional one, not everything is all artists and poets and croissants. People are poor. There is crime, and not just of the glamorous sort in mystery novels. Sometimes people are quite mean to each other, and sometimes they’re just indifferent in ways that have about the same effect as meanness. There is greed and selfishness a plenty.

A little part of me was sad last week at the comparison between my real town and the imaginary one in Three Pines. Mostly my sadness was about the spontaneous drop-ins that happen in the books, though I did notice that all the people doing the dropping in are childless, which would seem to make a difference. Also, the drop-in is one of those things that’s much better in theory than it is in practice. You think you want people to just drop by until they actually show up at your front door while you’re in your comfy pants.

All the same, I found myself wishing that I lived in a place like that. And then this Friday we sat at our regular spot at the 605 bar and got to see a friend who’d moved out of town come back for a visit. We heard a story from another friend about landing at an airport in Kentucky that didn’t have any gasoline. I watched one of the waiters at the 605 turn the menu around and read a description of one of the dishes out loud for someone who didn’t have their reading glasses with them, a small and easily missed act of kindness if you’re not looking for it.

Bridge construction from the river

Saturday morning, we helped another friend move into her new house downtown, an act of pure joy and community (especially when the moving only took an hour and a half) to help someone start a new life in a lovely new place, all the potential of an empty house stretching out in front of her. As we walked up to the house with our loads of lamps and boxes, we were immediately accosted by one of her new neighbors with a handful of tomatoes to give away, while her neighbor on the other side had sat a pot of mums on her front stoop.

We followed the morning moving with lunch at Shooter’s, where we ran into more friends at the bar there, one of whom joined us later in the day for a pontoon boat ride on the river. Riding up the river, we scared great blue herons in our passing, and saw them flying over the river like movable bomber planes. In one of the smaller creeks we went up, we saw dark spots in the water that turned out to be schools of minnow, swarming together in thick circles and lines under the water.

Sunday, we walked into a wine tasting at the 605 an hour late to be greeted by an actual round of applause and cheers, a sure sign that it must always be better to show up late. After discussing the possibility of a powder puff faculty football game at Hanover over wine and the best buttermilk biscuits I have ever tasted, we moved on to an art opening at JoeyG’s. And there we found our daughter, and friends, and neighbors, and lovely art, and a generally good time on a Sunday night.

I remember the first time I read the Buddhist idea that fantasies, living inside worlds in your head that don’t really exist, is not such a good idea all in all. I was horrified. I’ve spent a lot of time living inside my head, in a whole variety of worlds made up by me or other people. Three Pines is really just the latest in a long line.

There’s nothing wrong with having a healthy imagination; it’s part of what allows us to feel compassion and empathy. But look at how Three Pines almost made me miss the perfect village in which I already live. So maybe people don’t drop in, but instead we run into each other, quite often at a bar, which is definitely better in that there are less dishes to do. Maybe we don’t have croissant anymore, but the biscuits at the wine tasting on Sunday satisfied a deep longing inside me that I didn’t even know I had. Maybe there’s no carolling, but there’s folk festival and Chautauqua and countless other seasonal events.

The author who created Three Pines, according to her biography on the book jacket, lives in a small village south of Montreal. “Is it Three Pines?” I wondered to myself. “Could she really live in such a place, or did she make it sound much better than it actually is?” Who knows?

If you want to believe that the place you live is not at all like some imaginary ideal, than it never will be. This is for the simple reason that the ideal will blind you to all wonderful things that are already there. But if you give the place you live half a chance, you might find it’s actually better than that world inside your head.

In Three Pines versus Madison, Madison wins hands down.

Published on September 17, 2012 13:22

September 14, 2012

Riding the thought stream

In life, there’s always something. You’re bullshit because the weather sucks. There’s that troubling financial situation looming over your head. You have an annoying and untrustworthy colleague. As someone with an intimate relationship to anxiety, I can assure you that you can always find something to worry about if you’re so inclined.

And you can think to yourself, “Everything will be better after this passes.” After it rains or gets cooler. After you become independently wealthy. After your annoying colleague mysteriously disappears. And perhaps it will be better, but then something else will come along.

There’s always something, but we have the choice between being someone who is controlled by the things that happen to them, or being someone who understands that things just happen. The key to finding yourself in the latter category seems to be learning to ride the thought stream.

How to meditate

There are lots of different models out there that lay out the ideal relationship between you and your thoughts. Most of them center on what to do while you’re meditating, as you might think of meditating as like physical therapy. You get injured, you go the physical therapist and they show you some exercises. But the point is that the exercises will make your everyday movement easier. You practice the exercises at physical therapy in order to make it easier to climb the stairs or walk around. Meditation is like that. You do some exercises in order to make it easier to allow things to happen to you.

Sometimes this involves a mantra. Sometimes you concentrate on your breathing. Sometimes you try to get to ten (this is my least favorite kind of practice). In a yoga class I attended this summer, one of our instructors suggested you imagine yourself floating down to the bottom of the ocean. At the bottom, you watch from below as your thoughts float above, caught up in their own little thought stream. You watch them. You observe them. You let them go.

Letting go of a thought

Doesn’t that sound easy? To let go of a thought? When we draw thoughts, after all, they are clouds. They float above us. How easy does that imply it should be to just let go? Disconnect the little dots between your head and the thought and watch it float away? If we were honest about our connection to some of our thoughts, though, they’d be drawn more like a ball and chain. Or something velcro. Or perhaps they’d be like our favorite stuffed animal from childhood, which though it is old and smelly and perhaps riddled with disease, we continue to cling to for dear life.

I find the letting go of thoughts to be easiest after some yoga, lying on my mat in savasana, or corpse pose. I imagine myself floating down, more to the bottom of a swimming pool than an ocean, because I don’t know if you really want to be on the bottom of the ocean. And then I look up and watch my thoughts go by.

The mind is a wonderful thing, but it is stubborn. It is built of many familiar paths, and generally, letting go of your thoughts is not one of them. Letting go of your thoughts feels distinctly physical, an act of effort and will. Sometimes I vaguely expect sweat to break out on my forehead.

Sometimes I imagine the that the thoughts are floating by. Sometimes I imagine that I reach down into the water and disturb their images, like a reflection in a pond, before they have time to take hold. Sometimes I imagine them like bubbles, and I can almost hear the sound of them gently popping around me.

Laying there on the floor, working fairly hard at letting go of my thoughts, it feels like a lot. It’s hard. And what’s the point? There are a few moments every now and then when it seems to become easier, though I’m not always sure if that’s not because I’m just falling asleep.

And I guess all I can really say is this: things are easier on the days when I lie on the floor and pop the bubbles of my thoughts than they are on the days when I don’t. On the days when I lie on the floor, I can see that things will always be happening. I can see that most of the things that are “happening,” are not, in fact, happening to me right now, in the present. On those days, I can let go of thoughts even when I’m not lying on the floor, simply turning away from them while I’m washing the dishes or walking around town. I can say to myself, “I’m not going to think about that.”

On those days, I know that the world will never be perfect. Or perhaps I know that it already is.

Published on September 14, 2012 05:50