Joshua Unruh's Blog, page 5

October 31, 2012

So…What Do You Guys Want To Talk About?

Later this week, I'll tell you how a random conversation led to the new Consortium Books publishing plan where I write a book in the next six weeks for a near Christmas release. (I AM NOT DOING NANOWRIMO! THE TIMING IS COINCIDENTAL! BESIDES, IT'S MORE THAN ONE NOVEL!)

Later this week, I'll tell you how a random conversation led to the new Consortium Books publishing plan where I write a book in the next six weeks for a near Christmas release. (I AM NOT DOING NANOWRIMO! THE TIMING IS COINCIDENTAL! BESIDES, IT'S MORE THAN ONE NOVEL!)

Today, I'm hoping for some opinions. I have no idea if I'll get any because I have no idea what my readership is really like. I know a few people who read my blog, I glance at my Google Analytics now and then, but I make no real effort to attempt getting to know you unless you engage via comments.

That's not an indictment. I lurk on lots of blogs, or only comment rarely, so I can't fault anybody who does that here. However, by the same token, I don't expect those bloggers to give a rosy red rat's tuckus who I am unless I speak up. If they want to try and puzzle out who I am as a demographic that's fine with me. I can't comment on what people find enjoyable. Doing that to you guys sounds, to me, like getting dental surgery in North Korea.

But now I'm curious if I can get some input from my usual suspects and maybe even from some lurkers I assume exist somewhere out there. Let's find out!

I plan on returning to the writing advice for gamers because I'm turning that into a book later. I also plan on periodically doing some daddy blogging because my kid is awesome and funny, I'm even funnier, and those will eventually probably be a book also.

But other than that, it's all random topics in my head. Arrow is shockingly well written while the Green Arrow comic is so painfully off the rack I can't even muster the energy to be mad about it. Community is great. I like the concept of pulp television. Anthologies and short stories versus the traditional novel. My kid asked me to run a roleplaying game for him and I'm super excited. My regular RPG group is amazing and all noobs, there's a story there.

It's all random. And I'm happy to write about random stuff. But lately I've also been enjoying blogs that are random stuff AND non-random stuff. John Scalzi's Whatever is a fine example. He does commentary and political posts, sometimes of a very serious nature, and even when I disagree with them, they're well-written and fun. I bet I could do that!

But would anyone care?

That's where the informal questioning comes in. What would you guys like to hear from me? All random? Some non-random? Politics? Religion? Q&A? More writing advice? More gamer stuff? More general pop culture commentary? More general culture commentary? The voluminous but catch-all Other?

Tell me! Comment here, at Facebook, Twitter me (I love saying that, it sounds so dirty). Whatever. Just let me know.

And if I hear nothing, then I'll create a Blog Random Encounter Chart and roll on it, AD&D style! That actually sounds like fun!

October 23, 2012

Arrow Isn’t a Bullseye But Does Hit the Target

Being a fan of comics books, it was hard to miss when the CW network announced its latest foray into the world of superheroes. Arrow, named for the titular Green Arrow1, is a reimagining of the character into a world of nighttime dramatic action with all the tangled webs of relationships, secrets, hidden agendas, and people-who-are-not-what-they-seem.

Being a fan of comics books, it was hard to miss when the CW network announced its latest foray into the world of superheroes. Arrow, named for the titular Green Arrow1, is a reimagining of the character into a world of nighttime dramatic action with all the tangled webs of relationships, secrets, hidden agendas, and people-who-are-not-what-they-seem.

Generally speaking, I couldn't care less about Green Arrow. He's a blatant Batman knock-off with a ridiculous (even for superheroes) gimmick who got a thin coat of relevancy in the 70s by becoming super liberal and explaining to Green Lantern that, no matter how colorblind he was to interstellar species on Oa, he was still a racist douche at home. Then GA proved it to GL with an interminable road trip in a pickup truck.

That said, there have been some enjoyable Arrows. The animated GA on Justice League Unlimited was pretty enjoyable as the cantankerous old man who wanted all these new heroes to get off his lawn. In one of the very, very few examples of Smallville doing something right, it took the lemons of not being allowed to have Batman and made lemonade out of a Green Arrow who basically acted like a smirking Batman having fun running around in his silly outfit solving the world's problems. In a more serious vein, the Mike Grell penned Longbow Hunters era was a very well written grim-and-gritty take on GA when DC was all about rolling out as many badly written grim-and-gritty takes on superheroes as they could get paper for.

And the trailers and previews for Arrow definitely looked like Mike Grell and Christopher Nolan had a bow-wielding love child. But, for me, that's a half empty glass and I was leery of wasting any more time on another DC misstep2 with a character I was already marginal about at best.

But then the pilot aired and I was hearing shockingly good things from a lot of corners. And then I heard some very negative things from other corners. I sadly found myself in a place where I was going to have to decide not to care about Arrow at all or sit down and watch the damn pilot.

Well, needless to say, a couple folks made sure I couldn't just not care, so I sat down and watched the damn pilot.

And it was pretty okay! In fact, there are seeds of real, honest enjoyment mixed in there! I'm actually looking forward to watching the second episode!

The Good News

This show is totally watchable! I typically have to make apologies for pilots, but this one did the job of setting things up (including a slightly ludicrous number of interwoven relationships, mysterious backstories, and flashbacks) while giving a viewer a satisfying A plot to chew on.

I have a big soft spot for ridiculous relationship maps on nighttime action dramas, and some of the Arrow blanks were filled in with cliches or in heavy handed ways. But in a day and age where most pilots for shows like this are two parters, Arrow does a remarkable job setting up the series.

I also really enjoyed almost all the casting, especially of Ollie. That's hard on me since I liked the Smallville Ollie so much, but the only big casting misfire I could see was in Laurel. She's pretty much a blank canvas right now with some Rachel Dawes filled in around the edges, but that may be because they haven't decided if she's going to wind up Black Canary yet. (I hope not...)

The fight scenes were well staged for an untested television show. The A Plot made sense (more or less, see below in the Bad News). There were plenty of teasers for secrets and intrigue, which are pretty much mainstays for a show like this. And Arrow did not look like a total douche while firing arrows at guys with automatic weapons. That's a tough one to make work!

And, last but not least, there's one for the ladies and 10% of the dudes. Ollie is one delicious slab of beefcake.

Plus, best of all: Arrow through a Deathstroke mask. ARROW THROUGH A DEATHSTROKE MASK, PEOPLE!

The Bad News

WiFi arrows are dumb. I mean, I laughed and enjoyed it, but that's just silly.

If they make Laurel, a knock off version of a character so uninteresting even a switch from Katie Holmes to Maggy Gyllenhall couldn't invigorate her, into Black Canary, a character that has utterly surpassed Green Arrow in depth and interesting hooks, then I will burn down their houses.

They did leave out one of Ollie's typically trademark character traits, that being his crazy, left-wing politics. That's not saying left-wing politics are crazy, but Ollie is the left version of right-wing militia members. I'm honestly not sure how you work this in without making it the point of the show, but I throw this bone to whatever a Green Arrow purist looks like.

Speedy as the younger sister and it's her nickname because she already uses drugs.3

The aforementioned melodramatic cliches and somewhat hammy introduction of same. Honestly, I consider this a good thing in small doses, which was the case for Arrow, but I put it here also for the sake of fairness.

Ollie airbrushed green over his eyes instead of wearing a domino mask. Because airbrushing over your eyes is less stupid than a domino mask. (Hint: It isn't.)

Ummmm...that's it. Really. If you like urban vigilantes, melodrama, and nighttime action dramas, then you will call this a win. Even if you hate Green Arrow.

So, the Arrow pilot didn't suck. Nobody is more surprised than I am. I'll let you know what I think of the next episode.

1 Although the chromatic nomenclature was deemed too juvenile for this representation of the character despite his predilection for verdigris garb, Starling City is apparently way more grown up and serious than Star City.

2 I'm not going to get into a big thing here unless somebody really asks nicely, but two of those Nolan Batman movies are amazing pieces of film that are terrible, terrible Batman movies. The third one is just a terrible movie. It isn't even all that pretty. Therefore, the Nolan Batman movies are missteps in terms of being Batman movies. I don't care how much money they make, I don't care how masterful an artist Nolan is, they fail as movies about the character of Batman.

3 This almost made it into the good news. I mean, it's been decades of comics fans left amused at the irony so it's definitely time to bake the irony right in. So while I'm torn, I lean toward Good News but I recognize it's cheesey enough some might put it in the Bad News. After the last footnote, I threw you a bone.

October 9, 2012

From Tabletop to Paperback – Stealing Scenes

So I accidentally lied a little bit. I said I wasn't going to do anymore From Tabletop to Paperback stuff, but I was told from a couple of different corners that I could expand my thoughts on scenes a bit. Since scenes are the fundamental building blocks of the story, that made sense to me. It also works out because of how much a couple of new-school tabletop RPGs helped me understand the concept of framing scenes around scene questions.

Once again, I'm going to suggest playing both Dogs in the Vineyard and the Smallville RPG if you want help with framing scenes. I'll be using them as examples in this post often.

Setting the Stakes

Dogs in the Vineyard was the first game that told me to consciously set the stakes of any given scene. I'd been doing it instinctively for years (which is to say, sometimes amazingly and sometimes amazingly badly), but always as a natural consequence of having to tell a story. If nothing else, "will they or won't they get their faces eaten off" worked as a default stake.

But Dogs told me to set the stakes on purpose, with specificity, to get everyone at the table to agree on them, then, and only then, roll the dice so you can play to discover the outcome. That's pretty fantastic advice for a writer also with only a little shifting of the language. Set the stakes of the scene, make sure you know what outcome each character in the scene wants, then write the scene.

The Smallville RPG has you set the scene the same way but then you have to justify which Value and Relationship you roll in that scene based on the stakes. If Clark is trying to convince Lois he loves her, then he can use his Lois d10 I think Lois is the One. If Clark is trying to convince Lex he loves him, his d12 I can never trust Lex is harder to justify. Playing Smallville can be a real help to you as a mental tool if you find it difficult to define your written character's motivations in any given scene.

(Failing to) Write Toward An Outcome

Usually as a writer, you know how the scene is going to come out and you write towards that outcome. That's obviously different than the game where you're playing to discover outcomes. But everything up until the moment of rolling dice is great advice.

I say "usually" because there's a danger mixed in there. You might hear writers say "my characters took over." I don't really put a lot of stock in that statement because what it usually means is "I didn't plan my book very well." Sometimes, and this one has happened to me, you discover that one of the characters wants a different outcome than you originally intended or one of the set outcomes much more passionately than you thought. That's exciting stuff, there, and making sure you know what each scene is about helps you tell which is a lack of planning and which is exciting, grown-up writer stuff.

How The Stakes Get Set

This is actually a lot easier than you think. Remember that Story Question that you came up with before you even started prewriting? The one whose answer drives the entire narrative to some kind of resolution? Setting the stakes is just doing the same thing you did for your Story with the Story Question for the Scene with a Scene Question. What question for this scene will drive the narrative for this scene toward some kind of resolution for this scene.

Easy, right? Well, easier than setting a Story Question, anyway. And if you can't do that, you need to take a step back from individual scenes anyway.

Breaking Down The Scene

To make it easy, here are the steps to building a scene.

What is the Scene Question? Does it pit the Antagonist directly against the Protagonist?

Which character is the Antagonist? Which character is the Protagonist?

What outcome does the Antagonist desire from the scene? What outcome does the Protagonist desire from the scene? Be specific!

Figure out what setback the Protagonist will suffer during this scene. In other words, how will the Scene Question be answered "No" or "Yes, but..."?

Write the scene.

That's it! Obviously there are a lot of sub-steps in between each of those, but they're typically figured out through your prewriting. You know the Scene Question because you're driving to a Story Question. You know what outcome each character would want because you've fleshed them all out ahead of time. You know who needs to achieve what because you've mapped out the scene

October 4, 2012

From Tabletop to Paperback – Setting Setting to Awesome

On Tuesday, I explained what exactly Setting is in terms of our previously discussed Plot, Arc, and Character. This time, as in most of the second parts, I get to connect that to the stuff gamers are already good at or the stuff that entices us into bad writerly places. Let's accentuate the positive, though, and start with the good news.

Integration: Fitting It Together

Very much in passing, I mentioned Buffy the Vampire Slayer in the last post. I mentioned it because taking a "horror story" and placing it in an American high school set in sunny California let the writers refocus the lens into a metaphor that "high school is hell." They did it with overbearing parents literally taking over their kids' lives, boyfriends that became real soulless beasts once you slept with them, and even hung a lampshade on the powerlessness a lot of teenagers feel by making the entire infrastructure of a city evil.

Each season, for the most part, also had what became known as a Big Bad. There was an obvious Big Bad Monster, but there was usually a Big Bad Situation or Emotion that tied into the Monster or mirrored it in some way. That's just good writing (note that I learned that lesson from the Smallville RPG as well). Every episode had a plot, and even when they didn't directly tie into the Plot, they still advanced things the Plot needed.

And the characters, oh my, the characters. These are characters that honestly wouldn't have worked in any other setting. Cordelia the Queen Bitch, Xander the good guy stuck in the friend zone, Willow the girl struggling to break out of other people's misconceptions, Giles the wise yet flawed father figure, Snyder the evil principal, and Buffy herself, the teenage girl who feels like the weight of the world is on her shoulders.

This is great storytelling because the Plot, Characters, and Setting are entirely interdependent while also being completely separate. They could not exist without one another, yet also can't be confused with one another. A Hellmouth creates plot, but it's a setting. Giles advances plot, but he's a character. You get what I mean.

This is the kind of thing that traditional roleplaying games do well. And they've trained us to do it well. You create or purchase a detailed setting, there's all kinds of useful information in there (often in terms of rules, see below), but all that starts morphing and changing as players pick characters and the gamemaster starts putting together plots (which usually hinge on the characters).

That's the way these three should work together. Setting always gives way to (or spotlights) interesting plot which always gives way (or spotlights) interesting characters. Remember that in the modern novel, Character is king. Actually, that's not a bad thing to remember at your table if you're the gamemaster.

The Dangers of Lonely Fun

Just to get this out of the way, this section is not a cautionary tale about...self love. Stay on point, gang!

The opposite end of this spectrum is Lonely Fun. I can't recall where I first ran into this term, but it has become a favorite of mine. If you are gamers of a certain age, you might recall your gamemaster walking around with reams of notebook and graph paper covered in pencil scratchings and lovingly stuffed into a massive three ring binder. The boy created an entire world complete with thousands of years of history, cultures, fashions, dangerous places, nobles, commoners, ecosystems, and heaven knows what else. And he did it all before you sat down at the table.

That sounds like a great setting, right? Well, it was until you realized he also already had a story all set out for you and it didn't matter what your characters were or why they did what they did, they were going to play through that story no matter what. And if you tried to go off script, you were either told a flat "no" or you were summarily executed, or he grabbed you by the metaphorical nose and led you back around the plot.

This is generally called Railroading and is generally frowned on as not always very much fun. At least when the GM doesn't hide it well.

The reason this is a problem in terms of writing is, if you are the kind of GM that has done this and still does this, then you're going to have a hard time with fiction. Your setting has become more precious than your plot or your characters. The sheer volume of detail has locked you into place. You've reached the "quagmire of detail" I mentioned in part one.

And you thought that could only happen with real world settings. Well, JRR Tolkien and Robert Jordan have bad news for you.

Rules as a Manifestation of Setting

You may have noticed that Setting has a tendency to influence tone and themes. Not only that, but how you choose to engage your Setting can often adjust the nobs on things like Realism (with attendant items such as Sexism, Racism, Military Matters, Weapon Knowledge, History, et al), Seriousness, Frivolity, and a billion other areas. For the gamer turned author, it can be helpful to think of Setting in terms of rules because in tabletop RPGs, the rules often tell you what the game is really about.

You don't run an "epic adventure" with Moldvay Dungeons & Dragons. It isn't a game of heroic adventures, it's a game of exploration and resource management.

I've refrained from playing superhero games for most of my life, not in spite of my love for comics but because of it. Only recently are superhero games interested in telling comic book style stories. But something like Heroes or Alphas, stories about people with superhuman abilities who are not superheroes, would work great in most systems.

A serious, emotionally charged Post-Apocalyptic game is better served by Apocalypse World than Gamma World. A gonzo "dungeon crawl" set after the Apocalypse is better served by GW than AW.

The fourth edition of Dungeons & Dragons is a pretty amazing tactical combat simulator, but it's tougher to make it work on games of courtly intrigue. If you want to be able to do both well, you might choose The Shadow of Yesterday instead.

Nighttime drama (with superpowers) is a genre I literally couldn't imagine playing at the table until the Smallville roleplaying game came out. And now making a game about "Values" and "Relationships" is baked right into the rules, no hacking necessary.

For those of you who use a variety of systems, you understand exactly what I mean. Deciding on a rules set immediately focuses what your game will be about and how it will be about that. For those of you who adhere to a single system, you might recall a time you tried to use it to tell a very different type of story (perhaps some D&D4e lovers tried to do Game of Thrones), and realized you were ignoring and houseruling so many of the rules that you might as well have written your own game.

You single system users, I name drop a lot of different games in these posts. Go try a few of them out and see how the game you play (that is, the story you and your friends tell together) changes or refocuses itself. You'll probably see what I mean.

For those of you who already use multiple system users, it will help to think of Setting as the rules of your story. Is a gunshot wound a reason to call an ambulance or a minor annoyance? Will using drugs or having sex immediately lead to a character death? Will there be swinging from chandeliers or a lot of talking behind fans? Can you make both equally interesting.

And if it sounds like I'm saying Setting encompasses genre and category, then you're getting the point. If you've never thought of rules as suggesting or even dictating those things at your regular game night, then that sound you just heard was your mind blowing.

Scene Framing and Location Descriptions

And to end this section on a truly grand note, get ready for the thing that every gamer is already amazing at when it comes to Setting. You are, I virtually guarantee it, already spectacular at describing locations and framing scenes. You do both of these a hundred times a night at the game table. You might do it more if your the GM or depending on how your group manages narrative responsibility.

Don't believe me? Then you either don't GM much or you just haven't though of your GM responsibilities in this way. Let's start with the gamemasters. Whenever you enter a new room of a dungeon, attend the funeral of a king, walk into a dangerous copse of woods...I'm belaboring the point. Every time you act as your players' five senses, you're describing locations. That's obvious. But every time you start the action and set the stakes for it, even if those stakes are as simple as "does the monster eat their faces," you're setting scenes. It could be said that your job as GM really boils down to Location Description, Scene Setting, and Rules Knowledge. So, essentially, you do this author stuff constantly, albeit in a very specific way.

Now for the players. Describing settings is not usually a player's job in traditional RPGS. But if you've ever said something like, "I want to grab a hot pan and hit him with it and I know there's one handy because you said we were in the kitchens," then you have take a tentative step into location description by suggesting an important aspect of it. And if you haven't ever done this, try it! As for scene setting, if you've ever said along the lines of, "That's it, I'm mad at the Duke and I want to confront him about his lies in front of all these people and damn the consequences," then you've set a scene. You named the stakes, the principle players, and it's up to the playing to decide how it turns out. And again, if you've never tried this at the table, do it!

To practice setting a scene better, start trying to integrate some new information you don't usually give at the table as practice for writing. Tell the players how a place smells next time. Or describe the texture of a piece of clothing rather than telling them what it's worth. And if your players eyes tend to glaze over from the volume of information when they enter a new place, try to pare down your descriptions until each thing you tell them has immediate impact. The bonfire makes this room much brighter, penalty while your eyes adjust. The smell of the garbage chute is noxious, check for sickness. The One Ring is heavy to both body and soul, take fatigue levels.

If you want some help with scene setting, there are particular rules that will require you to do that well and more specifically. I'd suggest Dogs in the Vineyard (the first game that insisted I set the stakes for a scene by making sure the conflict was about one, very specific outcome) or Smallville (the first game I played that made Relationships and Values things you could not play the game without; every roll is something intrinsically important to your character).

And with that, we come to the end of From Tabletop to Paperback's first third. Now you know the places where you, as a gamer, are strong and also those where you are weak when it comes to writing fiction for the first time. I may take a break and blog about other things for a bit before tackling the second part where I contrast a beginning author with no gaming experience to a gaming veteran who first turns to the tyepwriter. Thanks for reading so far and keep on the lookout for more!

October 2, 2012

From Tabletop to Paperback – Setting the Settings on the Setting

Welcome back to another installment of From Tabletop to Paperback. Today we'll be talking about Setting. Setting is definitely a double edged sword for gamers with aspirations of writing. One the one hand, a great deal of games are billed as "settings" and there are whole campaigns consisting of "just" creating a setting and letting your players run rampant in it sandbox-style. On the other hand, these kinds of labors of love can become monolithic shibboleths so detailed that they actually become useless as Settings for Stories.

Welcome back to another installment of From Tabletop to Paperback. Today we'll be talking about Setting. Setting is definitely a double edged sword for gamers with aspirations of writing. One the one hand, a great deal of games are billed as "settings" and there are whole campaigns consisting of "just" creating a setting and letting your players run rampant in it sandbox-style. On the other hand, these kinds of labors of love can become monolithic shibboleths so detailed that they actually become useless as Settings for Stories.

Setting Defined

This is going to sound like I'm being a smart ass, but the honest definition of Setting is "the place where the story happens." This can be deceptively simple, though. Place can encompass things like "time period" or "culture." Even the obvious concept of "geographical location" can be a moving target. Are we talking about what city, state, country, planet? Or are we being specific as in "which house?" or "what floor of the building?" We've seen many stories, many of them truly amazing, with a singular setting.

Think of tv shows like "Cheers" or "The Office" where the setting is almost exclusively a particular bar or office. Think of movies like "Die Hard" where nonstop action occurs in a single office building. Or the favorite of Victorian literature that was so well loved it became a genre unto itself, the Locked Door Mystery. These are almost always set entirely in a specific house and its grounds.

So, I'm sure you all think you're very clever and know what Setting is. And, on an instinctual level, you're probably completely right. That said, after the last few chapters, it's probably worth reiterating what Setting is not.

Setting is not...

The Antagonist. Setting can generate antagonists (prison story filled with dangerous, desperate customers). Setting can make some antagonists better choices than others (nobody wants a pirate in their ninja movie...unless that's the point). Setting can even generate the Highly Visible Antagonist (systemic racism in the Deep South, for instance ..although even that should be embodied in an actual character). But the Setting is never, ever the Highly Visible Antagonist itself.

The Plot. Again, the Setting can generate plot (will he survive the lunch line on his first day in prison?). Setting will suggest plot points (the hero is inside an ancient temple, so there should be some traps and maybe even a mummy). The Plot can even dictate the Setting (samurai stories tend to happen in Japan in specific eras). But the Setting is never the Plot itself.

So while Plot, Antagonist, and Setting are all distinct things, they have obvious overlap. They aren't three separate pieces created in a vacuum from one another (usually), they influence and impact one another. Incidentally, that integration is a thing that gamers are already very good at, although we'll talk about that more in part two. Right now I want to talk about the Setting Trap.

The Setting Trap

The Setting Trap can be summed up in one word: Realism. Realism is dangerous. Realism has killed more stories than laziness, slush piles, and bad reviews combined. Realism can smother your story in the cradle.

Every time a helpful blogger writes an article entitled something like "What Every Writer Needs to Know about Guns/War/Medieval Society/Religion/Horses/Every Other Damn Thing," a puppy and a kitten die. In a cage match with each other.

Look, Setting forces you to make decisions which, in turn, forces you to have a bare minimum amount of knowledge about how some things work or don't work. Don't put silencers on revolvers and don't treat horses like motorcycles, that kind of thing. But don't ever feel like you have to be an expert on every little thing going on inside your Story. As long as you're an expert on telling a Story, and about your Story in particular, then you're in a good spot.

You should allow Setting to impact the story you want to tell at the Plot level. If you want a strong, non-Caucasian, female hero in a Victorian era story, please do that! But you have to realize that not addressing the racism and sexism of the era on some level will lose large swathes of your readership. But if the story isn't about the sexism and racism of the era, then you can feel free to treat it the same way action movies treat gunshot wounds: an inconvenience that could grow to become a real problem if the story needs it.

What I'm saying is, and what most people are really saying when they think they want realism, is you have to maintain verisimilitude. The rules you set for your story, including which parts of any given setting -- including a homebrew setting -- you choose, must remain logical in terms of themselves, must remain internally consistent, and must involve a very bare minimum of knowledge about the setting.

Just as I wrote these words, I happened to read a tweet wondering why Superman leaves contrails in the teaser trailer for next year's "Man of Steel." She insisted this was a science fail and, upon some Wikipedia reading, I found she's absolutely right. At first, I had a moment of sadness, but then I immediately decided to not give a crap. Contrails have a scientific reason, but for story purposes, they mean "this thing flies really fast." With that in mind, contrails are the best decision that trailer could have made.

Realism versus Verisimilitude. If you could only have one, which one would you choose? There's only one right answer for a maker of fiction.

But Setting Also Sets You Free

A traditional horror story becomes a metaphor for high school as hell thanks to setting. Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew becomes a tale of high school drama thanks to setting (along with some significant shifts in plot points and character along the way). A hardboiled detective story similarly becomes a whole other flavor of story when the setting becomes a southern California high school. Adding an element like magic to a Chicago outside your window creates a whole new landscape against which to tell stories. A Western, but in space.

All these ideas are Settings with a twist or multiple Settings mashed together. Each of these stylistic choices were made in order to tell stories that could not be told in any other way or to tell old stories through a fresh lens. While the realism of any given Setting can certainly trap you in a quagmire of details that drags the narrative to a halt, the unlimited nature of being able to do whatever you want with a Setting, even if it's tear a few apart to create new Settings from bits of old ones like a patchwork quilt of awesome.

Setting can set you free. Free to retell old stories, free to reimagine stories, free to filter stories until they become different stories, or so free that you start out to retell a story and, thanks to the changes imposed by the setting, your mind finds itself free to rewrite rather than retell. Probably more than characters or plot, it's Setting that forces me to think in new and different ways. And that's pretty amazing.

There are a couple other ways that Setting can trip you up, like creating a Story that serves the Setting rather than the other way around. There are a couple more ways that Setting can make your life easier, like allowing the Setting to dictate the scope of your story. While both these pinnacles and pitfalls are far from unique among novice writers, they tend to loom a bit larger (for both good and ill) over the the gamer turned writer. Which is why I'll deal with them more on Thursday. See you then!

September 27, 2012

Protagonist Powers

In yet another "Superman v. Batman" conversation on the internet, I was appalled at the sheer lack of scholarship that goes into this debate. Now, I know what you're thinking. Not everybody spends as much time preoccupied by these things as I do. And that's totally fair. In fact, I normally cut people a lot of slack for exactly that reason. It also makes me more aware of not sounding like a talking goat to experts on any given subject.

In yet another "Superman v. Batman" conversation on the internet, I was appalled at the sheer lack of scholarship that goes into this debate. Now, I know what you're thinking. Not everybody spends as much time preoccupied by these things as I do. And that's totally fair. In fact, I normally cut people a lot of slack for exactly that reason. It also makes me more aware of not sounding like a talking goat to experts on any given subject.

But in this case, I feel utterly justified. These were writers and they were making classic blunders that writers should know better than to make. I'm not going to link to the post because, honestly, I don't want to offend anyone over there even though, and I say this knowing how inflammatory it is, most of the statements were bone jarring stupid.

Hyperbole, you say? Let me demonstrate by paraphrasing a comment.

Superman is a less compelling character than Batman because he's overpowered. He has the powers to do whatever he wants but Batman is just a mere mortal.

People...no. Just...no.

I know it looks like a reasonable statement, and in the real world, it would be. But this is the world of Story. And in the world of Story, the Protagonist is almighty.

Protagonist Powers

Superman can fly, bullets bounce off him, he has super senses to solve crimes, he can freeze stuff with his breath, and burn stuff with his eyes. That's all really impressive stuff, I admit. Now let's contrast this with Batman.

Batman can fly (with a jet), bullets bounce off him (or his suit, or he's just magically not where they are), he has a super mind to solve crimes, he can pretty much do whatever makes any kind of reasonable sense with something from his utility belt (freezing and burning are easy).

In terms of Story, Batman and Superman (and Indiana Jones and James Bond and Captain America and Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers and...you get the idea) have exactly the same power level. Because in adventure fiction, the hero is always in danger (although the definition of danger certainly changes depending on the hero), but he always overcomes the danger (in a way that makes sense for that hero) and wins in the end.

How do they manage this? They use their Protagonist Powers. And the protagonist's main power is, frankly, to overcome insurmountable odds and win by the time the author types the words THE END.

Sniper Rifles and Eye Rolls

When I insisted this was the case, another seemingly reasonable statement was made. It looked sorta like this.

Superman is always Superman, even when he's Clark Kent. When Batman is Bruce Wayne, he's vulnerable. Put each of them in the crosshairs of a sniper rifle, and only one of them is in danger.

There is all kinds of stuff wrong with this whole idea. The most basic one, the idea of identity, demonstrates a fundamental lack in understanding of both these characters. Neither one of them is fundamentally Superhero or Secret Identity. Both of them play roles in either set of clothes while the Real Person lies somewhere in between.

But that's specifically about Superman and Batman. I'm talking about Protagonists. Once again, a fundamental underlying concept of Story is deeply neglected here. Neither of these fictional people is in any real danger if a sniper is pointing a rifle at them.

I'm not just being meta (although there is a meta aspect to it). These are Protagonists! They may be hurt by the bullet (and in this specific case, the definition of hurt is very different), but they will not be killed or even permanently injured.

Bruce Wayne will not be shot through the heart and instantly die because if he did, then there wouldn't be a Batman anymore and we cannot have that. But he will be scuffed up pretty good and the wound will slow him down significantly at a very inopportune moment, which is when he'll overcome and succeed.

Clark Kent will not be shot through the heart and instantly die because he is, in-fiction, bulletproof. Or at least his skin is. If Clark Kent is shot by a sniper rifle, then the world will know that he and Superman are one and the same. This will be psychologically scarring and the (psychic) wound will slow him down significantly at a very inopportune moment, which is when he'll overcome and succeed.

Notice the similarity there?

While the definitions of danger may vary wildly in-fiction, the Protagonist is nevertheless in danger. One is in danger of dying (though we don't actually ever think he really will) and the other is in danger of losing a part of his life big enough to feel like he's dying (though we don't actually think he really will).

Ignorance, Themes, and Tones

When people say they prefer Batman stories over Superman stories because of power levels, they are one of three things.

They are ignorant. And this is totally fine. Not everybody spends all day thinking about this stuff. But if you claim to, you better realize that what you're really saying is that writers have done a terrible job of convincing you that Superman is in danger.

They are talking about theme. Batman is a man who overcomes tragedy by fighting the force that ruined his life. That's a pretty amazing theme. Superman is a man who overcomes the fear of the unknown by using his gifts to make the world a better place. That's also a pretty amazing theme. But, as we are all jaded and cynical in this modern world, one theme is perceived as "sexier" than the other.

They are talking about tone.

Batman lives in a world of murky shadows where he is at least as scary as his villains who are all dangerously twisted and psychotic caricatures of the hero.

Superman lives in a bright world of sunshine and gee-whiz super science where he is a beacon of hope even against villains who would use their extraordinary gifts for greed and ego, thus becoming a caricature of the hero.

You may prefer one of these tones over the other, but that doesn't make the character who fits that tone better than the other. It doesn't make any story emulating Tone A instantly better than one emulating Tone B. It doesn't, in short, make Batman a fundamentally better character than Superman. It just means you prefer his tone.

And there's nothing wrong with that.

I just wanted to take a thousand words to make sure everyone understood what they were really talking about.

September 25, 2012

From Tabletop to Paperback – You’ll Love the Arc So Much You’ll Plotz

Since I am a writer and make magic with words (spell and spelling come from the same root, same with grammar and grimoire), then I am sort of a wizard. And a wizard is never late, nor is he early, he arrives precisely when he means to. And he brings his blog posts with him. Finally, with no further preamble or nonsense, here is part two of Plots and Arcs.

The Good

In most traditional, GMful tabletop roleplaying games, the stuff we described in the previous post as Plot is actually happening all the time. It's the prime motivator of most sessions. There might be a Highly Visible Antagonist, but there might just as easily be a dragon nobody has ever heard of before sitting on top of a pile of treasure you want. A lot of very traditional RPGs have moved toward a place where your character's Arc matters, but a lot of them leave that up to you and mainly give you rules on how to kill things and take their stuff.

Because of that, this is where we gamers shine. When have you ever been able to get to the Dark Priest's enclave without passing through a troll-infested, haunted swamp? Or moved your mysterious and illegal cargo without outrunning an Imperial blockade? Or when as your decker cruised up to some sweet looking information and downloaded it without cracking the ICE?

What's more, all of this informs the Final Boss Encounter. Are you hurt? Are you tired? Did you use all your spells? Did some of your party die? All of these things impact heavily on how the end of your Plot happens.

"But wait," you might be saying, "you just called that the end of our Plot. What happened to the Arcs?"

Unfortunately, in most traditional, GMful tabletop games, Arcs are something that don't happen often or only do so when they've become the Plot.

The Bad

A lot of very entertaining RPGs are very Encounter based and Combat focused. That was actually the only way to play when I was a kid (at least as far as I knew in a relatively small city in northwestern Oklahoma before there was an internet to bring all the nerds together). But still, many of us had elaborate backstories for our characters because, since we read science fiction and fantasy novels, watched cartoons, and read comics book, that's how all our favorite heroes worked. Luke's dad was the big villain, Aragorn ran from his destiny and birthright, Superman was rocketed from his dying planet, you get the idea.

Clever and enterprising gamemasters would take this information and make it part of the game. You had to find and take revenge on your father's murderer, for instance. If that was your character, you were playing at least half an Arc. If it was the rest of the group, they were just playing more plot. Oh, maybe they had roleplaying reasons to do so since you were great compatriots and adventurers together, and that's totally great! But for play purposes, for most of the group, it was more plot.

Again, smart GMs moved that spotlight and looked for ways to shine it on different PCs. But even so, for the table it was Plot and for the spotlight character, it was half an Arc. Why half? Because it was just the stuff that happened without any emotional connection. Your hero found his father's killer, fought him in honorable combat, and won. You might take his stuff or make an enemy of whoever his boss was, and some of that would make a difference in the next Plot. But how did your hero feel about that win? Is he satisfied? Did it leave him unfulfilled? Is he still consumed with anger or has he discovered new found peace?

Even if you were an amazing player who really wanted to engage the fiction -- and did so, either in your own head or writing it all down for your fellow players to enjoy -- this was rarely reflected in the mechanics. The technology just wasn't there. If it didn't make you swing your sword harder or shoot your blaster straighter, it was "Fluff."*

And that can be a disconnect when you move to writing. Modern audiences are in love with character. They want the Plot to demonstrate the character's makeup and they want it to factor into or reflect his Arc, but the Story is effectively the Arc. We'd all be bored to tears without the Plot (because remember, it's the stuff that happens and makes the story exciting), but we're unsatisfied if we don't see how this is reflected in the character's emotions or worldview.

For the flip side of this coin, I submit to you without much comment Epics. Nobody cares how Beowful feels about things. Same for Achilles and Odysseus. They may have motivations that tie into their emotions and worldview, but there is no first person naval gazing going on there because audiences of antiquity wouldn't have cared.

Fluff is Story is Arc. That stuff that couldn't (until more recently; see the footnote) be reflected on your character sheet is the stuff that will make or break the resolution of your story. Gamers are amazing at Plot, and that's going to make the story exciting. The hobby may or may not have given a gamer-turned-writer the tools to manage the Arc, and that's where you make the resolution satisfying.

The Ugly

The Ugly is, as you may recall from part one, the Highly Visible Antagonist. Since the HVA is often directly tied to the Main Character (Darth and Luke, Sauron corrupted Aragorn's line, Humperdink stole Westley's girl) and is directly opposed to him/her, gamers can have a hard time getting a handle on what is and what is not a Highly Visible Antagonist. This is especially muddied when so many henchmen or situations feel like antagonists and are highly visible (high speed chases, bombs strapped to chest, dudes in white armor shooting lasers at you).

Don't get me wrong, guys, that's three fingers at least. I struggled and wrestled with this, found myself in arguments with my coach/publisher about it where I honestly didn't understand what I was doing wrong, and finally threw up my hands and waited for divine revelation. What I got instead of that was this post.

Because reading these two posts together, you can probably see why the HVA is such a difficult concept to grasp coming from a traditional tabletop background. A Story's Highly Visible Antagonist and its effect on the hero could not be reflected mechanically in a traditional game. You could make it happen, and I did at various times get those two things to connect, but it was not easy.

It took a special kind of GM and a special kind of player to first find each other in what has been a pretty niche hobby most of my life. Then they had to combine their forces to reflect the important emotional/story aspects of the PC in a way that, at best, ignored the rules and, at worst, openly defied them. Then they had to do it in a way that either swept up the rest of the group or, at the very least, didn't annoy the hell out of them.

Once I started playing a few Story Games (again, see the footnote) and started writing fiction with more regularity, I finally started to pull this together and understand why my highly visible antagonists weren't Highly Visible Antagonists. It's because most traditional, tabletop RPGs don't have a Story Question for my HVA to yell "NO!" to. Without that, nothing rises above the level of trying to kill the hero or make his life somehow miserable.

There it is! The Good, the Bad, and the cautionary Ugly! I've had another interesting technique swim into my vision this week that I'm calling Protagonist Powers. I'll be writing about that on Thursday, but next week I'll be back with From Tabletop to Paperback as we talk about Setting.

*Some modern roleplaying games, sometimes called Story Games, do an amazing job of representing the emotional state of your character. Margaret Weiss Productions's RPG based on the TV show Smallville is a stellar example of this. PCs in Smallville don't even have traditional stats, they have Relationships and Values. Lumpley Games's Dogs in the Vineyard strikes a strong balance between this by giving PCs more traditional stats, but also skills and abilities that are tied directly into your character's identity or backstory as well as relationships, all of which impact the rules with the same weight. Check these games out specifically -- and a host of other Story Games -- if you want a little help with Arc at the table.

September 18, 2012

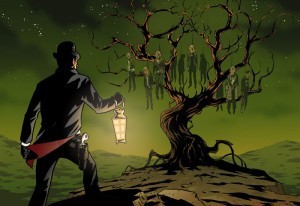

The Nicest Thing I Can Say – A Review of The Sixth Gun

Over the weekend I came down with an unpleasant cold with a side order of debilitating fever. It took me out of the game for the two days I'd set aside to write the second part of my ongoing how-to series. So that's still coming, but it's too rough to post today. Instead, I'm going to do a mini-review of a comic book series I recently discovered called The Sixth Gun. It gets my stamp of approval because it made me say the nicest thing I can say about any piece of fiction I read.

The Sixth Gun made me want to write.

The Sixth Gun made me want to write.

Written by Cullen Bunn and set in a recently post-Civil War America, The Sixth Gun is a Weird Western tale of six evil guns with horrible magic powers. The weapons bond themselves to a single living person until that person dies at which point the next person to touch the gun becomes the new owner. My favorite part of Bunn's writing on this is how every character either wears a hat of pitch black or, at best, one of smoky, dirty gray.

Those pitch black hats are undead Civil War generals, his vain and vicious widow, and Civil War criminals willing to follow the aforementioned undead general. Seriously, how much do you love all of that? Evil magic guns, undead Confederate generals and their wicked crews? There is nothing in there not to fall into a swoon over.

The "heroes," though, are where this series shines. And they all wear hats of gray. As a fan of Noir, that couldn't make me happier. I love that. Drake Sinclair, a dandy gunfighter with a very shady past, never does anything for just one reason. But he does enough protective, "good guy" things that you can almost forget he's a self-interested bastard. Naturally, he's bonded to four of the six guns. He seems to hate that fact, but he also went in with eyes wide open so he must be up to something...

Most of Drake's protective moves are for Becky, a young girl who accidentally found herself bonded to the Sixth Gun which gives the gift of prophecy or insight. That sounds like a pretty great power, but at the same time, everyone is at pains to explain to Becky that the gun serves only its own interests, never the interests of its owner. Becky took up the gun without realizing what was happening to her, so she's as close to a victim as you get. But that doesn't mean she's pure as the driven snow.

Gord Cantrell is an ex-slave and leader of men with a wealth of occult knowledge. He seems interested in helping Drake and Becky  manage the evil of the guns, but he's also got dangerous secrets lurking in his past that might suggest he's traded bits of himself for power and revenge before.

manage the evil of the guns, but he's also got dangerous secrets lurking in his past that might suggest he's traded bits of himself for power and revenge before.

Standing in the middle are Kirby Hale, a handsome gunfighter/bounty hunter that strikes me as a sinister Brett Maverick, the Sword of Abraham, an evil-fighting order of Catholic priests who have fought the evil of the guns for millennia, and Asher Cobb, a mummy with the gift of prophecy, and Pinkerton detectives with a connection to the Knights Templar. These are the secondary characters, people! How amazing is that?

The art is equally amazing. Brian Hurtt drew some of my favorite books of all time including an arc on Queen & Country, Gotham Central, and unfortunately short-lived Hard Time. He's had to master the American West's deserts, the city, swamps, and bayous of New Orleans, prison camps, flashbacks to other times, Catholic missions all look beautiful and hideous or both at the same time.

Not to mention the fantastical creatures like ghosts, demons, thunderbirds, loa, golem-style zombies as well as the stock Western characters of gunfighter, thug, miner, codger, sheriff, and all the others you remember from Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Good, The Bad, & The Ugly. The art works as both fantasy story, traditional Western, and murky Spaghetti Western.

The book is a tremendous read with 50 issues (bound together in three collections with a fourth on the way in November) and it deserves to be read by you. GO BUY IT! The first issue is free on Comixology and each "volume" is bundled together for $8.99. That's a tough deal to beat, but your local comic shop will hook you up if you prefer the dead tree version.

The book is a tremendous read with 50 issues (bound together in three collections with a fourth on the way in November) and it deserves to be read by you. GO BUY IT! The first issue is free on Comixology and each "volume" is bundled together for $8.99. That's a tough deal to beat, but your local comic shop will hook you up if you prefer the dead tree version.

I couldn't recommend this series more. In fact, as I mentioned above, I have the nicest words I can say about it: It made me want to write. That'll be good news for you guys as well.

As longtime readers will recall, I have a Weird Western languishing unpublished. This is mostly because it was my first finished novel. For those of you that don't know the curse of the first novel, that means it is a horrible mess of a manuscript. It is such a mess, in fact, that it has been easier to just write new things than to fix it. Well, no more!

Hell Bent for Leather has demons and a gun full of blessed magic and a cowboy roped (see what I did there?) into a a larger world full of evil monsters and Devils that make deals for your best friend's soul. It also has a finished but unpolished sequel titled On Leather Wings with definitely non-sparkly vampire-type things.

I'm looking to polish Hell Bent and release it as a serialized novella via Amazon's new Serials project. That lets me fix it in smaller, bite-sized chunks and release it to you as I do so. That's super exciting to me and, I hope, to you guys also. So celebrate some Unruh-style Weird Western fun by reading Mr. Bunn's and Mr. Hurtt's supernatural rollercoaster ride across the Old West today!

Tomorrow (not literally) you can celebrate by buying mine. I won't be jealous in the meantime, I promise.

September 13, 2012

From Tabletop to Paperback – Plot: A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum

For the beginning writer, the first part of talking about Plot is realizing what it does and does not mean. It's such a nebulous concept that it requires defining before we can even discuss it. For my purposes, Plot is not the big, over-arching story of the narrative. Plot is the stuff that happens in between bits of the big, over-arching story of the narrative. What people typically call plot is actually a (Story or Character) Arc that answers a Story Question. We'll talk more about establishing Story Questions later, but the basic definition is pretty self-explanatory: what's the question that this narrative will answer?

For example:

Will Harry Potter find the Sorcerer's Stone?

Will Luke Skywalker get to leave home and do exciting, galaxy-changing things?

Will the crew of Battlestar Galactica make it to safety and freedom on Earth?

Will Westley marry his true love, Buttercup?

Can Alice escape from Wonderland?

You'll note that most of those Story Questions are barely addressed throughout the narrative itself except in the barest sense. Alice not getting lost and keeping her head on her shoulders (literally) are necessary to escape Wonderland, but they don't immediately impact the question. Harry does find the Stone but it's almost a deus ex machina and it's the "year at school" that gets the majority of screen time.

I could come up with a hundred examples of this, but the bottom line is this. "Will they get to the forum?" is Arc, "the funny things that happen on the way to the forum" is Plot.

For example:

A mirror showing Harry's one true desire threatens to overwhelm him

Luke negotiates with a scruffy nerfherder of a freighter pilot to get off his home planet.

A terrorist from the prison ship wants to run for president.

Westley dies.

Alice apparently trips balls with a hookah-smoking caterpillar.

That's foundational, memorable, important stuff, but it doesn't actually answer the Story Question because it's Plot.

Scene Questions v. Story Questions

This doesn't mean that your Plot Heavy scenes (the smallest building block of the story) can't or don't feed into the Story Question. In the bar where Luke Skywalker will negotiate passage off his home planet, he's nearly killed because he doesn't understand the rules in this rougher world. That vignette throws a bigger question mark on the Story Question. Or in the Harry Potter example, the mirror tells us something amazingly fundamental about Harry's Character Arc while setting up the solution to the Question.

The whole story is tied together when these kinds of things happen in individual scenes. This is even, or perhaps especially, true if the reader doesn't realize it until the resolution. Never underestimate the power of a truly grand "AH-HA!" moment. What this does not mean, though, is that every single scene has to have some big payoff at the resolution. Nor is each scene forced to somehow inform the larger question. Sometimes the cigar (that's filled with poison to kill the person about to light it up) is just a (deathtrap) cigar.

You might think of these types of Scene Questions -- Questions like Will they be eaten by alligators? or Will she make it to work on time? or Will the first date be horribly awkward? -- as the bread in the meal that is your story. If done well, a flavorful bread can enhance the rest of the meal, pull the individual dishes together, thicken a light course into a full serving, and, lastly, sop up the plate at the end. New writers might call this filler, but that's how you can tell they're new. These are the things that make up a story.

Dots Are Great...But You Have to Connect Them

More on this in part two, but the good news is that gamers are actually already very good at Plot. Non-gamer new writers that don't fall into the fluff camp usually never even realize the meal they're cooking is incomplete without the warm, enticing loaf of Plot.

More than once, I've had a writer I'm coaching say something like, "I knew exactly where my story was going to go, so I started writing it. I'm halfway through my plot outline and the thing is coming up way way short. What should I do?"

When I took a look at the manuscripts in question, I discovered that the freight train of Arc had come a'roarin' in with a full head of steam and left no room for anything else. It was like somebody took the dots from a connect-the-dots puzzle and decided the whole thing would work better if you just piled the dots on top of one another.

But neither puzzles nor stories really work that way. You've got to spread those dots out, man! Put them in some kind of sensible order that gives the outline of a picture! Then, and this is pretty key, you get out a pencil and you actually fill in the lines to finish the picture! I know, I know. that just sounds crazy, right?

But it's exactly how your story should work. Your Arc gives you the dots, without which there's no pattern to follow. You can't live without the dots for certain, but it's the lines that actually turn the whole thing into a picture. The lines create the actual finished shape. And it's the shape of the thing that people are going to remember.

Highly Visible Antagonists

This next piece of advice has been a tough nut for me to crack personally. It's one of the few places my gaming experience actually got in the way of my storytelling. In the next part of Plot, I'll explain how to (hopefully) avoid all the painful time I've spent coming to understand this concept. Before we get there, though, I have to point out the Elephant in the Narrative Room: the Highly Visible Antagonist.

Your Arc must have a Highly Visible Antagonist. Just in case you aren't sure what this means, think about Sauron, Darth Vader, Lex Luthor, Prince Humperdink, Khan, Agent Smith, and a thousand other guys you could name. The HVA is the really obvious, in-your-face threat who kicks your whole story into motion. These are the guys who steal the McGuffin, kidnap the damsel, blow up the planet, try to kill all the good guys, or commit whatever dastardly plot they're getting up to.

Now, this is going to sound ridiculous, but this is actually a point I still struggle with. The most important thing to remember about this Antagonist is that he is Highly Visible. These guys loom over the narrative landscape. (Perhaps like some sort of all-seeing, burning eye at the top of a black tower or something...)

For contrast, let me demonstrate some antagonists that are not particularly visible. Storm Troopers are a good example. They're scary guys in armor and helmets just like Vader, but you don't see any of them crushing throats. Orcs are ugly as sin, but they're a near numberless horde. Deserts that try to kill you with thirst, or avalanches, high-speed chases, horrific first dates, voyages through stormy seas, multiple suitors, gunfights with henchmen...these are all antagonizing forces. But they're sub-antagonists to the HVA. They are scene antagonists, here today and gone tomorrow.

Now, to me, guys shooting at you are pretty damn highly visible. So are vast deserts with no food or water. That bomb strapped to your chest? That thing is pretty visible, right? But in terms of your narrative arc, these things are obviously not the Highly Visible Antagonist. They might be minions of the HVA (Storm Troopers and orcs), they might be between your hero and the Highly Visible Antagonist (the desert or high-speed chase), they might alienate the damsel you're supposed to be rescuing (horrific first date), but they are demonstrably not the Highly Visible Antagonist.

And this is the reason we make such a stark contrast between Arcs and Plot. You can move the Arc along with Plot, typically by using antagonists who are connected directly to the Highly Visible One. You can also simply make your hero's life interesting with antagonists who are not connected to the Highly Visible Antagonist while nevertheless being dangerous, deadly, embarrassing, or just getting in the way of the hero answering his Story Question.

And what, at the end of the day, is the main thing that separates a scene antagonist from its Highly Visible older brother? A scene antagonist wants the opposite of what the hero wants in that scene. But the Highly Visible Antagonist wants the answer to the Story Question to be a (usually) big, fat NO.

NO, Darth Vader doesn't want Luke Skywalker changing the galaxy for the better. NO, Sauron doesn't want the One Ring destroyed. NO, the Cylons don't want the Galactica to make it to Earth. NO, Voldemort doesn't want Harry to live long enough to graduate. NO, Humperdinck doesn't want Westley to marry Buttercup because he wants to marry her. NO, Agent Smith doesn't want Neo to do...whatever it was Neo was supposed to do.

Or, just to be clear, if the hero wants a no, then the Highly Visible Antagonist wants a YES. Those are just a bit rarer, though.

It's that vehement and direct opposition to the hero's Story Question that makes the Antagonist Highly Visible.

So, now that the foundation is laid, next time I'll explain how gamers are already in a great position to make use of Plot and pad their stories out into much more robust and exciting shapes. But I'll also point out, both for me personally and in a more general way, that our good habits at the tabletop can trip us up when we hit the keyboard.

September 11, 2012

From Tabletop to Paperback – Chargen Part 2

So last Thursday I talked about how hard it is to make good, three dimensional characters and how difficult it is for a lot of burgeoning writers. I also swore that I'd show you, the gamer with designs on writing fiction, how prepared you are to create exactly those kinds of characters. Trust me on this, if you've been playing RPGs for any length of time, you can do this and do it well. Here are a few of the keys to compelling characters and how rolling 3d6 over and over has already done the heavy lifting for you.

Larger Than Life Characters

Nobody ever rolled up a portly, balding middle manager at a small accounting firm in Cleveland for their adventuring party. Not unless the normalcy is meant to contrast with the living nightmares that are about to attack every corner of his nice, quiet, suburban life. Every character is hellbent on revenge, or a superhero, or a barbarian warrior destined to be king, or a keen-eyed wizard, or, at the very least, an attractive orphan who wants to delve deep into the earth in order to brave its dangers and come back with treasure.

What I'm trying to say is nobody sets out to play an average character. Even if their stats are just okay, good players are looking for ways to carve out their niche at the table. They're creating big personalities. They're just waiting for the moment they can say something like, "my character gambles a little...but he isn't very good at it." Whatever it is, you always always give your character some kind of interesting hook that sets them above the pile. The kind of thing that, when you mention it, makes your GM's eyes gleam devilishly.

Sometimes you have to do this because the system is generic. The player has to bring everything distinctive to the PC because the mechanics have a sameness. I found this to be true in most flavors of Dungeons & Dragons. There are three fighters in your party...so what is it that makes yours so special? An indie game that nods in the direction of Old School Dungeoneering, Sage Kobold's Dungeon World, deals with this by declaring that you are THE Fighter. Oh there are other people who wield swords, but none of them compare to your skill at arms. You're THE Magic User. There may be other conjurers and shamans, but your Arcane wisdom is supreme.

But whether it's in spite of the system or baked right in, whether it's epic fantasy, superheroes, cyberpunk revolutionaries, or swashbuckling pirates, you're already used to thinking of your RPG character as the center of the universe. His enemies join him in the center of the universe by virtue of being his enemies. This is an attitude you must apply to your story's characters.

Nuanced Characters

In this context, nuance is the myriad things I vaguely know about my characters that let me predict random facts like their favorite colors. It's the backgrounds, the towns they came from, the socioeconomic status they grew up in, the religion they belong to, the hundred million little things that you know because you know the top eight things about their lives before the adventure begins.

Nuance is knowing the interests and beliefs of your character that have absolutely nothing to do with the plot. Of course you know what god the paladin follows, but what about your fighter that grew up a dirt grubbing peasant? Does he still pay homage to the goddess of grain, or did he leave that behind when he left the farm? If you've ever been blindsided by your gamemaster with an unexpected question that you nevertheless were able to answer in-character without thinking because you just knew what you're character would do, then you're on the road to nuanced characters.

Flawed Characters

One danger that a lot of beginner writers fall into is protecting their characters. The knife isn't twisted as hard as it should be, the punches aren't as bruising, and the cherished character, usually the hero, walk around with a kind of plot armor protecting them from the worst the story has to offer. When you combine this with the "amoeba" syndrome," you stray into very lackluster territory even if you're command of language and story structure is otherwise good.

One symptom of that plot armor is forgetting that your characters need flaws. This isn't always protecting the characters. Sometimes it's just an added problem with not fleshing your characters out in the first place. But between these two beginner mistakes, you often wind up with unassailable heroes and indestructible villains. That's not only unrealistic (everybody has some flaws), but it winds up being boring and, ultimately, unrelatable.

Marvel v. DC (c. 1963)

This isn't an RPG example, but it's a great one that's near and dear to my heart. By the 1960s, superhero comics were selling again (after a massive lull throughout the 1950s). There was no Marvel Comics at this point, DC was the main game in town. For those of you not in the know, that's Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, Wonder Woman, et al. These guys were total whitebread; square-jawed heroes through and through. They were, each and every one, totally unflawed. Oh sure, there was Kryptonite for Superman and Green Lantern's ring didn't work on yellow objects, but those are Plot, not Character.

In comes young upstart publisher Marvel Comics. They decided to position themselves as the "world outside your window" superhero universe. That meant heroes and villains with actual, honest to goodness character flaws. Peter Parker is wracked by guilt, has an ailing aunt, is perpetually broke, and girls don't like him. The Thing is a dashing pilot now trapped in the body of a monster by his best friend. Mr. Fantastic is the best friend, so another wracked by guilt situation. Thor is so full of himself that he's kicked out of Asgard to learn humility. Iron Man is a drunk, Daredevil is a lawyer by day and vigilante by night. The X-Men protect people who hate and fear them.

These were heroes with feet of clay. Compared to the Distinguished Competition, these were heroes you could believe in because they were created in a lab to appeal to teenagers. Everything is louder than everything else in those early Marvel comics, and the flaws still somehow manage to be loudest of all. It was such a revolutionary idea that, by the mid 70s, DC had basically emulated the formula. They'd emulate it even harder when they restarted their entire line and shared universe in 1985.

Flaws, Drawbacks, Vices...Just Gimme the Points!

Just like I mentioned, new writers have trouble giving their characters flaws. Once they get over that hurdle, they tend to give all their characters the same flaw. Even veterans can fall prey to this (I'm looking at you, Wheel of Time and your perpetual gender idiocy). But it isn't enough to just give characters flaws, they have to be interesting flaws.

All of you already do this. You might have started doing it just because so many rules systems reward you with more positive stuff for taking negative stuff (Champions and Savage Worlds to name just two of thousands). Maybe your mind shifted when you realized that you could take an Enemy for points but then suddenly declared that he'd killed your character's father. Maybe you just thought you were clever taking schizophrenia and you ran into a GM who made your other personality the villain of the plot. Whatever it was, at some point, you realized that your PC's flaws could also make her interesting.

If you haven't made this switch yet, try to do it consciously the next time you roll up a character. If you can convince your group to change systems, look for a rules that reward you for your flaws not just in chargen but also when these flaws come up in play. Better yet, when you bring them up. Then, and this is important, don't beat that drum until it breaks. Look for the best moment for your guy to be clumsy or greedy. Better yet, look for the worst moment.

Flaws With a Twist

Maybe characters aren't your strong suit. Maybe you've been perfectly happy to play a Fighter and the only difference between him and the other fighter you played is this one uses a halberd. If so, then you may find yourself falling into the beginner habits of not characterizing or over-protectiveness. Here's a favorite trick of mine that I like to use on my protagonists who are actually Big Damn Heroes and, therefore, pretty uniquely without flaws.

I create opportunities for their virtues and strengths to become vices and weaknesses. Maybe they're famous, so they have to rely on a secondary, and less skilled, character to infiltrate the villain's hideout. Perhaps they have a huge and supportive family, which they run into when pretending to be somebody else. They could have a vast capacity for violence, but they happen to indulge in it right in front of the news crew. Whatever it is, I spend a few scenes turning whatever I viewed as their greatest strength into their greatest weakness.

Characters That Tempt FATE

If you want some practice with good character building at the game table, I have a recommendation. The best for both making interesting characters whose strengths are also weaknesses is probably a FATE game, such as Spirit of the Century or The Dresden Files RPG. In FATE, characters have Aspects as part of their stat block. These Aspects are descriptive phrases that tell you things about the character. Harry Dresden is a Wizard Private Detective. I made a Tarzan type who was a Hairy Chested Love God. There's a million of these, your options are literally endless.

What's more, a lot of FATE systems walk you through your character's life history. So your first two Aspects have to do with your childhood, the next two have to do with your teen years, the next two are when you started adventuring, and the rest tie you to the other characters. So your PC might have Grown Up On the Streets, but then was taken in and Mentored by an Aging Hero. Aspects cannot help but force you to make more interesting, three dimensional characters.

Aspects usually help your character. You pay a Plot Point (an in-game currency without which you'll be a very poor hero indeed) to give yourself a boost where your background or high concept comes into play. Fairly obvious and straight forward. But to me, that's not the true joy of Aspects. The flip side of Aspects is when the GM actually pays you a Plot Point when he uses your Aspect as a complication.

Wizard Detectives get a Plot Point when they have to answer to the council of wizards. Hairy Chest Love Gods get a Plot Point when some important NPC's wife finds him irresistible. Characters with Family In Every Town get a Plot Point when Aunt Petunia wants to tell the King all about her embarrassing childhood stories.

Aspects are brilliant and a great way to practice the things that are going to make your story's characters come alive for your readers.

Next time, we'll talk about another area gamers don't typically have a problem with in stories: Plot! Also known as When Stuff Happens To Your Characters. See you then!