Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 77

September 9, 2023

Inspired in the twenty-first century by fifteenth century art

THE WORD ‘INSPIRATION’ has at least two meanings. One of them is ‘to breathe in (i.e., inhale air). When air is inhaled, many of the oxygen molecules it contains are converted to become other substances, some of which is carbon dioxide that is exhaled. Another meaning of the word is to be mentally stimulated, often by something one has perceived in the world around us. What results from this form of inspiration might not much resemble whatever it was that caused it. Today (the 6th of August 2023), we visited a small exhibition in one room of London’s National Gallery. Showing until the 29th of October 2023, the exhibition is called “Paula Rego: Crivelli’s Garden”.

The exhibition contains two major works: “La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)” painted in about 1490 by Carlo Crivelli (c1435-1495); and “Crivelli’s Garden” painted in the early 1990s by Paola Rego (1935-2022) when she was the National Gallery’s first Associate Artist between 1990 and 1992. There are also some sketches that Rego made for her enormous painting, originally designed to be a mural.

Both the Crivelli and the Rego paintings are excellent, but quite different in style. However, Rego was inspired to create her mural after seeing Crivelli’s altarpiece. Although both paintings are of religious subjects, there is no obvious similarity between the two of them. As Paola Rego said in 1992:

“If the story is ‘given’ I take liberties with it to make it conform to my own experiences and to be outrageous.”

And that is what she has done after having been inspired by Crivelli’s masterpiece.

The paintings at the base of Crivelli’s altarpiece (the ‘predella’) include scenes set in gardens. According to the National Gallery’s website, what Rego did was to reimagine:

“…Crivelli’s house and garden to explore the narratives of women in biblical history and folklore based on paintings across the collection and stories from the medieval Golden Legend. Her figures inspired by the Virgin Mary, Saint Catherine, Mary Magdalene and Delilah, share the stage with other women from biblical and mythological histories.”

She has populated her picture with portraits of people she knew including (to quote the website again):

“…friends, members of her family and staff at the National Gallery whom she asked to sit for her, including Erika Langmuir, Lizzie Perrotte and Ailsa Bhattacharya who were members of the Education Department at the time.”

The resulting work is both beautiful and fascinating, but quite different from the 15th century work which had inspired her.

Whether your artistic preferences are for art created during the Italian Renaissance or in the late 20th century, this small exhibition will not disappoint you. If you enjoy both, as I do, then this inspiring show of artistic inspiration is a ‘must see’ event.

September 8, 2023

From Zambia to the moon and Mars

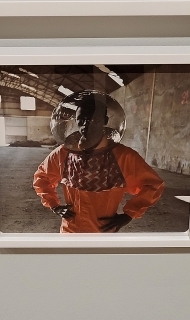

UNTIL THE 14TH OF JANUARY 2024, there is a fascinating exhibition at London’s Tate Modern gallery. Called “A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography”, this is a display of a wide variety of photographic works (still and cinematographic) showing various aspects of life in the African continent past and present. Although many of the exhibits were both eye-catching and fascinating, one – a series of photographs by Cristina de Middel (born 1975) – interested me especially. Titled “Afronauts series 2012”, it commemorates a project, which few people remember outside Zambia.

Between 1960 and 1969, the founder of the Zambia National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy, Edward Festus Mukuka Nkoloso (1919–1989), worked on Zambia’s space programme. During a period when the USSR and the USA were competing to make advances in space exploration, Nkoloso felt that Zambia and the rest of Africa should join the space race. His aim was to launch a rocket, which would transport two cats, an astronaut, and a Christian missionary, to the moon. 17-year-old Ms Matha Mwambwa was chosen to be the first ‘afronaut’. After landing on the moon, they were to have been sent onwards to Mars.

Nkoloso set up a training camp near Lusaka. A website (https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/zambian-space-programme) describes this:

“In an attempt to achieve this mission to the Moon Nkoloso recruited twelve astronauts, and put them through rigorous training of his own devising. He put them in an oil drum, spun them round trees and rolled them down hills in order to prepare them for weightlessness. He taught them to walk on their hands as he believed this to be the way to walk in space. He made them swing on a rope, before cutting the rope to allow them to experience freefall.”

Despite seeking funding from various countries – always unsuccessfully – the programme failed. In addition to lack of funding, other disasters hit the project before it could take-off from the ground. These are described in the website already quoted:

“Mwamba fell pregnant and returned home. Other astronauts left, reportedly going on drinking sprees and never returning or moving onto other pastimes such as tribal song and dance. And with no astronauts and no money, the Moon can seem awfully far away.”

De Middel’s exhibit at the Tate Modern is loosely based on the story of Zambia’s space programme. She has combined fact with fiction to produce a series of photographs depicting fantasy images of the failed project. Some of her photographs show afronauts wearing glass domes on their heads instead of astronauts’ helmets. De Middel’s elderly grandmother made the costumes worn by the subjects posing as afronauts. The artist’s image show simulations of space travel that are very distant from the images issued by NASA and other space exploration agencies. In a way, the exhibit asks the question: “Who is it that gets to explore space?”

I am pleased that I saw the exhibition, which is well-displayed and often thought-provoking. However, I am extremely happy that by visiting this show, I learned about an almost forgotten competitor in the space race. Recently, India landed a mission on the moon. Maybe, it is now Africa’s turn to make space exploration history.

September 7, 2023

Farewell to an old friend in the heart of London

OVER THE PAST 45 YEARS (or more), we have eaten at least once a year at the India Club restaurant in London’s Strand. Occupying the first and second floors of the old-fashioned Hotel Strand Continental, the Club’s bar on the first floor is reached via a steep, narrow staircase. Opposite it, there is an office and reception area where our friend Mr Marker, or one of his daughters, greets us. Another narrow staircase ascends to the dining area on the second floor.

The Club was founded either just before India became independent in 1947, or in the very early 1950s. Close to the Indian High Commission, Bush House, and the London School of Economics, it was designed to be a home-away-from-home for Indians in London. The Club’s website (www.theindiaclub.co.uk/our-story) mentioned that the Club:

“… was originally set up by the India League, to further Indo-British friendship in the post-independence era, and it quickly became a base for groups serving the Asian community … The Indian Journalist Association, Indian Workers Association and Indian Socialist Group of Britain were just some of the groups which used 143 Strand for their events and activities. The building was also a base for the new wings of the India League which ran a free legal advice bureau and a research and study unit from this address.”

One of its founding members was Krishna Menon (1896-1974) who was independent India’s first High Commissioner to London. Soon after it was founded, the Club became popular with non-Indians as well as those for whom it was founded. Supplying Indian cuisine at very reasonable prices, the restaurant became a popular eatery. Until a few years ago, alcohol was only available to paid-up members of the Club. To become a member, and thereby have the use of the bar, an annual membership fee of only £1 was payable. Later, the Club’s restaurant must have obtained an alcohol licence because the requirement to become a member (for the purposes of purchasing booze) was dropped.

Both the restaurant and the bar have always looked like they must have done when the Club was first opened so many decades ago. Consequently, the place has an old-fashioned look about it. Should one of its founding members wander in today, they would have found little changed, except the prices. For us, and I suspect many other regulars, part of the charm of the Club was its unchanging appearance. It seemed to me that the management have deliberately not done anything to spoil the early postwar atmosphere of the place. The Club is adorned with paintings and photographs, mainly depicting notable Indians who lived during the period when India was becoming independent. To quote the website again:

“The interior of 143 Strand, particularly the characterful and distinct entrance, stairwells, reception area, first floor bar and second floor restaurant, remain in the same condition as they were during the occupation of the property by the India League. As a result,143 Strand’s interior allows it’s historical and cultural associations to be experienced first-hand by the public. It is the only building in the capital connected to the India League that has not been redeveloped or re-purposed. It therefore remains living history.”

As for the food served at the Club, over the years it has varied in quality according to who was working in the kitchen. Always satisfactory and good value, the Club’s food could never be described as exceptionally good. The menu included both vegetarian and non-veg dishes. I always enjoyed rounding off the meal with the excellent kulfi they served.

A few weeks ago in August 2023, a friend in Bombay (Mumbai) sent me an upsetting newspaper article. It quoted the Club’s owner Mr Marker as saying:

“It is with a very heavy heart that we announce the closure of the India Club, with our last day open to the public on September 17.”

Bearing this in mind, yesterday (Monday, the 4th of September 2023), a small group of us decided to have a last supper at the Club – to say farewell to this wonderful relic. When we arrived at the Club at 6pm, I could hardly believe my eyes. There was a queue of people waiting to dine at the Club. The line stretch from the pavement, up both flights of stairs, to the restaurant, which was chock full of diners. I had never seen the dining room with such a large crowd. The bar was also full of people waiting to get a table. When we learned that we would have to wait at least 45 minutes to be seated, we decided to go elsewhere (to Sagar Indian vegetarian restaurant in Panton Street).

It was various news items about its imminent closure that drew us and all the other people to the Club. Some of them, like Lopa and I, were regulars, but I wondered how many of the other folk queuing that Monday evening had ever eaten at the Club. Did its impending closure, like the film “Oppenheimer” and the play “Dr Semmelweis” – both about figures known mostly to scientists, draw the crowds to a fairly unfamiliar place that had suddenly become attractive because it was soon to be no more?

September 6, 2023

Kutch from kingdom to district

MY WIFE’S COUSIN lives in a part of the Indian state of Gujarat called Kutch (‘Kachchh’). He and his wife have a lovely farmhouse near the port city of Mandvi, where you can watch huge wooden dhows being constructed along the riverbank. Although Kutch is now a part of the state of Gujarat, it has not always been. The people of Kutch (‘Kutchis’) speak a language quite distinct from Gujarati. The Kutchi language has closer similarity to Sindhi than to any other Indian language (Kutch is bordered to its north by Sindhi speaking people*). It is a spoken language, but not written. Even though Kutchi people can speak and write in Gujarati, they will proudly inform you that they are Kutchis and definitely not Gujaratis. During our several visits to Kutch, my wife’s cousin’s driver, who can speak good Gujarati, insists on speaking to my wife in Kutchi, which she cannot speak as well as Gujarati.

Many people with whom I have discussed my travels, look puzzled when I say that we have been to Kutch. Just in case you are wondering, it is the furthest west part of India. Most of the north of the region is bordered by Pakistan, from which it is separated by the arid Rann of Kutch. To the south and separated from it by the Gulf of Kutch (a part of the Arabian Sea) is the peninsula of Saurashtra – now also a part of Gujarat.

Until 1947, Kutch was a kingdom founded by unifying three separate kingdoms, ruled by branches of the Jadeja family, in the 16th century. In 1819, having suffered a military defeat (at The Battle of Bhuj in March 1819), the Kingdom of Kutch accepted the sovereignty of the British East India Company. Under the watchful eyes of the British, members of the Jadeja family continued to rule Kutch – it became one of India’s many ‘Princely States’. On the 16th of August 1947, one day after India became independent, Kutch voluntarily acceded to the new Indian state.

Kutch became a state of India. In November 1956, as a result of the State Reorganisation Act (1956), Kutch ceased to be a state in its own right, but became a part of the then huge Bombay State. The latter was effectively a bilingual region, most people were either speakers of Marathi or of Gujarati. The Marathis and the Gujaratis began to clash. In 1956, the Mahagujarat Movement began campaigning for a state for Gujaratis, which was separated from that for Marathis. The movement was spearheaded by Indulal Yagnik (1892-1972). His nephew, who lives in Bangalore is a family friend, whom we meet whenever we are in the city. As the Gujaratis clamoured for their own state, so did the Marathis, Blood was shed, and much property was damaged. On the 1st of May 1960, the old Bombay state was divided along linguistic grounds. The states of Maharashtra and Gujarat were formed. The latter includes the Gujarati speaking district of Saurashtra as well as the northern part of the former Bombay State, and also Kutch. And that is how it remains today.

Since 2017, we have made several enjoyable visits to Kutch, from which my wife’s maternal ancestors hail, and enjoyed many fascinating experiences there. Some of these can be found in my new book – a collection of true stories about life in India seen through my eyes. The book (also Kindle) is available from Amazon websites including https://www.amazon.co.uk/HITLER-LOCK-OTHER-TALES-INDIA/dp/B0CFM5JNX5/

*When Lord Napier conquered Sindh *which neighbours Kutch) in 1843, he is reputed to have sent a single word message to London in Latin “Peccavi”, which means ‘I have sinned’.

September 5, 2023

Delicious!

Call it a gherkin

Or a pickl’d cucumber

Tasty by any name

September 4, 2023

Advertisements in a cookery book for Malaya

IT IS CURIOUS how some things, heard once long ago, stick in one’s memory. When I was a little boy, I remember my father telling me that there was a product called Klim. I thought he must be joking because Klim is ‘milk’ spelled backwards and my father did have a sense of humour. For example, when we used to visit Italy, he used to say “a penne for your sauce” (instead of ‘ a penny for your thoughts’).

A few years ago, some friends were clearing out some books and gave me a few of them. One of them was “Cookery Book of Malaya”. It was published in 1951 by the YWCA of Malaya and Singapore. Remember that Malaya only became known as ‘Malaysia’ in 1963.

It was only today (1st of September 2023) that I decided to have a look at this book. Edited by Mrs AE Llewellyn, the volume is packed with information about nutrition and recipes. The recipes include many western dishes as well as a selection of “Malay”, “Javanese”, “Chinese”, “Indo-Malayan”, and Indian, recipes. Most of the book is written in English but the section on “Methods of Cooking” is bilingual: English and Malay. I suppose this was so that the British housewives could instruct their Malay cooks.

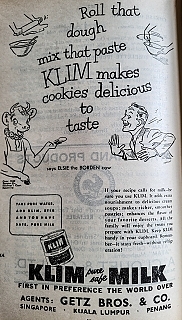

The book has several pages of advertisements. Four of these are for milk – mainly the powdered variety. To my great delight, one of them is for Klim. The advert says:

“Take pure water, add Klim, stir, and you have safe, pure milk.”

Another part of the same advert says:

“Keep KLIM handy in your cupboard. Remember – it stays fresh – without refrigeration.”

Klim has been around a long time. According to Wikipedia:

“In 1920 Klim was a product of Merrell-Soule Company of Syracuse, New York which in 1907 had improved the spray-drying method patented by Robert Stauf in 1901 by starting with condensed milk instead of regular milk. In 1927 Borden acquired Merrell-Soule gaining the Klim brand and None Such Mincemeat, both already made popular worldwide.”

The Nestlé company acquired Klim from Borden in 1998. Although I have never noticed it in any of the many shops I have visited, it is still sold worldwide.

I am pleased that I finally got around to opening the old cookbook because it contained the advertisement that confirmed that by mentioning Klim my father was not simply pulling my leg.

September 3, 2023

A painting full of meaning with a pair of severed feet

DURING MY CHILDHOOD, my parents took my sister and me to Florence (Italy) every year. We spent a great deal of our time there looking at renaissance and earlier paintings. Apart from their beauty, my father was particularly interested in the symbolic meanings of things included in the paintings. On a recent visit to the chapel of King’s College in Cambridge, we saw a painting that reminded me of my father’s love of interpreting symbols in old paintings of religious subjects.

The painting is “Madonna in the Rosary” painted by Gert van Lon, who was born in Geseke, Germany in about 1465. The painting was created between 1512 and 1520 for a nunnery in the German town of Soest. The crowned Madonna and Child is surrounded by an oval frame of painted roses. There is a pair of angels in the top left and right corners of the picture, and two kneeling nuns (holding rosaries) in the lower left and right corners. The thing that both puzzled and surprised me are two severed feet, each with their toes pointing at the nuns. Each foot has a red spot, denoting a wound made by a nail on the Cross. Each foot has been depicted as if it had been cleanly and recently sawn from the legs to which they were attached.

In an article published about this painting in The Burlington Magazine (June 2012) by Jean Michel Massing and Aurélie Petiot, the severed feet are representations of the wounds of Christ. The baby Jesus is held in the Madonna’s left hand and there is a bowl of cherries in her right hand. According to the authors of the article:

“In religious symbolism the cherry stands for the heavenly reward for piety, while its sweet-sourness alludes, in typological terms, to the joys and sorrows of the Virgin.Mother and Child…”

And the garlands of roses surrounding the Virgin and Child represent Hail Marys. They are separated by the feet, already mentioned, and by a pair of hands that also represent Christ’s wounds. Each of the sawn-off hands has a nail wound. My late father, who subscribed to The Burlington for many years, would have loved explaining all of this to us.

The painting, so I learned from the article, was donated to King’s College by Charles Robert Ashbee

(1863–1942). He was an architect, social reformer, designer, and important member of the Arts and Crafts Movement. He had studied as an undergraduate at King’s College between 1883 and 1886. It was Ashbee who designed the wooden frame surrounding the painting.

Although I have visited King’s College Chapel many times, it was only on my recent visit in August 2023 that I first noticed Gert van Lon’s painting that is both beautiful and full of meaning.

September 2, 2023

A Hungarian pensioner at Kings College Cambridge

DURING A RECENT VISIT to Cambridge, we spent some time in the magnificent chapel of King’s College. It is difficult to avert one’s eyes from the masterpiece of gothic fan-vaulting that forms the ceiling of this edifice, but it is worth doing so because the chapel is filled with other wonderful things. These include a painting by Rubens, another by Gert van der Lon, and yet another by Girolamo Siciolante de Sermoneta. The brass lectern that stands in the choir was made in the early 16th century and is surmounted by a small statue of King Henry VI. There are many other items of great historical interest to be seen including the stained-glass windows, which have survived since the 16th century. Interesting as all of these are, what caught my attention was something in a small side chapel – The Chapel of All Souls.

This chapel was converted in the 1920s to house a memorial to those members of King’s College (academics, students, choristers, and servants) who died during WW1. The names of those who perished are listed on engraved stone panels on one wall of the small chapel. Amongst these names is that of the famous poet Rupert Brooke (1887-1915).

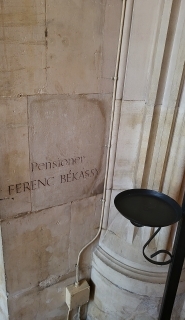

On another wall of the chapel, separate from the list of names, I spotted an inscription carved into the stone. It reads:

“Pensioner Ferenc Békassy”

Ferenc Istvan Dénes Gyula Békássy (1893-1915) was a Hungarian poet born in Hungary. In 1905, he was enrolled at Bedale’s School in Hampshire. In 1911, he began studying history at King’s College Cambridge. He was what is known as a ‘pensioner’. In Cambridge University usage, this word was used for a student, who has no scholarship and pays for his tuition as well as his board and lodging. During his time at the college, he was elected a member of The Apostles and courted the same woman as Rupert Brooke. He composed poetry both in Hungarian and English.

Just before the outbreak of WW1, Ferenc returned to Hungary, where he enlisted as a hussar in the Austro-Hungarian Army. On the 22nd of October 1915 he was killed in action whilst fighting the Russians in Bukovina. He was buried on his family’s estate in Hungary.

After the war, the memorial in King’s College Chapel was established. Because it was considered objectionable for the name of an enemy soldier to be listed amongst those who fought and died for Britain, his name was not included on the memorial. Instead, it was placed on another wall nearby.

Though separated from Rupert Brooke’s name by a few feet, this small chapel serves as a memorial to two great poets, who were killed in their prime.

September 1, 2023

A faceless baptismal font in a small town in Hertfordshire

HITCHIN IS A SMALL, attractive town in Hertfordshire. When we first visited it in 2020, despite an easing of the covid19 lockdown rules, we were unable to enter the town’s 14th to 15th century church of St Mary’s. On the 26th of August 2023, we spent a couple of hours in Hitchin and were able to enter the church. It contains many items of interest including a large painting created in the studio of Ruben’s.

It was the 15th century carved stone font that particularly interested me. The column supporting the bowl, which contains water with which children are baptised, has twelve carved figures. These depict the 12 apostles. Looking at these closely, you will see that they are all mutilated. Their faces have been chipped away, leaving the figures faceless.

The very helpful and informative gentleman who was looking after the church was not sure whether the faces were obliterated by Thomas Cromwell during the Reformation of Henry VIII or during the time of that other iconoclast Oliver Cromwell.

Luckily the carved angels that adorn the ceiling of the Chapel of St Andrew and a finely carved 15th century wooden screen escaped the attention of the iconoclasts. In one or two Suffolk churches we have visited, angels such as these were destroyed as part of the attempts to ‘purify’ the English Church.

Apart from what I have described, there are plenty of other things that make a visit to Hitchin’s church worthwhile. And if you enjoy ‘Olde Worlde’ British buildings, the town centre is rich in them.

August 31, 2023

Embroidering in Palestine past and present

THERE IS A SUPERB exhibition at Cambridge’s Kettles Yard until the end of October 2023. The beautiful exhibits are mainly garments embroidered by Palestinian women before and after 1947. There are also a few other items including Palestinian propaganda posters depicting women wearing embroidered garments. The labels next to the exhibits are full of interesting information. Several of the topics particularly interested me.

Some of the garments were made using scraps of pre-used materials – for example bits of old clothes or even sacking and other packing materials. These old textiles were stitched together to create new clothes. This reminded me of a similar recycling of old materials which I saw at an exhibition of Japanese recycling at London’s Brunei Gallery.

I saw examples of Palestinian dresses which seemed very long. The length of these skirts was for a purpose. The cloth could be raised up to produce pocket like folds in which objects could be carried. These dresses were worn by Bedouins living in the Bethlehem and Jerusalem areas.

There was a widow’s dress. It was dark blue – the colour signifying grieving – and trimmed with red threads, which signified that the wearer was ready to be remarried.

One room was dedicated to embroidery and how the troubled situation in Palestine affected it. In refugee camps, some of the traditional materials were unavailable, and women had to embroider using whatever threads they could get hold of. There were several embroidered dresses adorned with decorations including the Palestinian flag and other patriotic motifs. These were displayed in the same room as the pro-Palestine propaganda posters that show women wearing embroidered garments.

I hope that what I have written gives you something of the flavour of this fascinating exhibition. Despite the intense reactions that discussing the plight of the Palestinians often arouses, the exhibition at Kettles Yard takes a reasonably balanced view of the situation. Its emphasis is on the skills of the Palestinian embroiderers rather than the politics of the part of the world where some of them still reside.