Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 76

September 19, 2023

It is always gratifying if any of my books are reviewed

IN EARLY OCTOBER 2022. I published a book about London’s Golders Green and its neighbour Hampstead Garden Suburb. It was the part of northwest London where I spent my childhood and early adult life. I wrote about areas’ past and present, and my memories of living there. The book sells reasonably well by my modest standards, but was not reviewed until early September 2023. Then someone in Germany awarded the book 5 stars (out of 5 stars), and reviewed it on Amazon as follows:

“A very informative and often funny book! I immensely enjoyed reading it.”

Brief as it is, this reviewer encapsulated what I was aiming to do when writing my book. That was, to write something that was both elucidating and amusing.

I am always happy when someone takes the trouble to review one of my books. Naturally, I would prefer a favourable review, but a critical one is also welcome. That a reader bothers to post a review shows that he or she has read the book and reflected on its contents. I find that very gratifying.

The book about which I have been writing is called “GOLDERS GREEN & HAMPSTEAD GARDEN SUBURB: VISIONS OF ARCADIA” and is available as both a paperback and a Kindle from Amazon websites, such as:

September 18, 2023

In search of a new warm coat in London and Manhattan

JUST BEFORE I VISITED New York City in early 1992, I needed to buy a new coat. I entered Cordings gentleman’s clothing store on London’s Piccadilly and was greeted by a salesman. He listened carefully whilst I explained that what I was seeking had to be warm, windproof, waterproof, lightweight, and furnished with pockets both outside and inside the garment. After a moment’s consideration, he said to me:

“What you need is a Dannimac, Sir.”

I asked him whether I could see one and try it on. He replied:

“There’s only one problem, Sir.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“They don’t make ‘em anymore.”

So, I set off for New York with an old coat that needed replacing. One day, I entered a clothing store on the lower east side of Manhattan. I explained my requirements to the very talkative salesman. When I explained my pocket requirement. He said abruptly:

“You want pockets on the inside and the outside? What are you? A private detective? A secret agent?”

That was the first, and so far, only time, someone has suggested that I did that kind of work. The man showed me some feather-filled puffy jackets made by North Face. They fulfilled all my criteria. I chose a beige one, and happily parted with over 100 US Dollars. I used that North Face for over 25 years until its appearance became too disreputable, and then, sadly, I disposed of it.

Having acquired my fine new coat, I had to get rid of the old one, which I had brought from England. I recall that there were few if any rubbish bins on the streets. As for my friend’s flat, where I was staying, there seemed to be nowhere to dispose of even the smallest bit of rubbish. On my return to the UK, my future wife, who had lived in New York City, explained that there must have been a rubbish disposal shoot in the flat or the building. I did not want to dump the old coat in the street, So, in the end, I handed it to one of the many people begging for money in the city.

September 17, 2023

Travelling by air in 1919

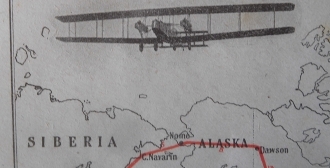

AT THE END OF WW1, in 1919, there were two ways of travelling by air. Either by aeroplane or by airship (powered balloons, such as the famous Zeppelins). Airships could travel without stopping for longer distances than ‘planes, but they moved less quickly. You might be wondering how I discovered this, and why am I suddenly telling you about it. Well, yesterday, my wife bought me a copy of “The New Illustrated” in a charity shop. It was a slightly used copy of Volume 1, number 1, published on the 15th of February 1919. Edited by John Alexander Hammerton (1871-1949), it was a successor to his journal “War Illustrated”, which was disbanded in February 1919, a few days before “The New Illustrated” was launched. The first issue of the new magazine came with a “Map of the World’s Airways”, given away as a gift. It is from this map that the information in this essay is derived.

The map of the world shows routes taken both by airships and aeroplanes, and the flying times between stops. For example, from Cairo to Aden was 25 hours by airship non-stop, and about 13 ½ hours by ‘plane, not including a stop in Suakin (in northeast Sudan). By air across the Atlantic, there were two choices: airship from London to St Johns (Canada), 36 ¾ hours, then ‘plane St Johns to New York with one stop, about 12 hours flying time; or airship from London to Halifax (Canada), 46 ¾ hours, then ‘plane to New York 6 hours non-stop. The timings given on the map assumed that an airship travelled at 60 mph, and a ‘plane at 100 mph. The map only displayed what it called “All British” routes.

These days, we travel between Bangalore (not far from Madras) in India and vice vera taking about 11 hours non-stop, or about 12 hours (flying time) with a stop in the Arabian Gulf States. In 1919, the traveller from London to British India had two choices. From London to Karachi (now in Pakistan) by ‘plane took two days and 10 hours, and stopped in Gibraltar, Malta, Cyprus, Baghdad, Basra, and Bahrein Island. Alternatively, you could fly by ‘plane from London to Bombay in two days and 17 hours, stopping on the way in Gibraltar, Malta, Cairo, Suakin, Aden, and Socotra Island. From Bombay to Madras was another seven hours by ‘plane. Long as these journeys might seem to us today, we must remember that travelling by sea was far slower. For example, when my wife travelled on a P&O liner – a regular passenger service, not a cruise – from Bombay to Tilbury in 1963, the trip took at least a fortnight.

If, by chance, you had wished to circumnavigate the world, you could do it by airship in 16 days and 18 hours via India, or 18 days and 10 hours via South Africa.

While I was writing this, I remembered the father of some close friends. He worked for the Shell oil company. I remember him telling us that when he used to fly to Africa and the Far East during the 1950s, the ‘planes did not fly at night. So, each flight was made in stages. Every evening during the journey, the passengers would disembark and were put up in a hotel until the flight was resumed the following morning. Seeing the 1919 map reminded me of what he told us many years ago.

September 16, 2023

An artist who campaigned against slavery

HE WAS PASSIONATE about sketching and painting. However, his father, a wealthy Quaker brewer in Hitchin (Hertfordshire), insisted that his son should dedicate himself to working in the family business and use his spare time to create his art. The artist was Samuel Lucas (1805-1870). There is a wonderful exhibition of his creations at the beautifully laid out North Hertfordshire Museum in central Hitchin until the 12th of November 2023.

After schooling and an apprenticeship in London’s Wapping, Samuel worked in the family business in London before returning to work in Hitchin in 1834. As for his artistic ability, this appears to be self-taught. However, he was a keen visitor to the Royal Academy exhibitions in London. In 1837, he married Matilda Holmes, who had been a pupil of the artist John Bernay Crome (1794-1842). She was keen on sketching, but none of her works have survived. I speculate that it is not beyond possibility that Matilda, a water colourist, might have helped Samuel develop his superb water colour techniques.

Samuel’s sketches range from extremely detailed to impressionistic, resembling the work of JMW Turner to some considerable extent. The finished oil paintings, some of which were displayed at the Royal Academy, are beautifully composed, full of detail, and of great visual interest.

Two of the exhibits interested me more than the others. One of them is a pen and ink sketch depicting Thomas Whiting of Hitchin reading Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (published 1852) to a gathering of people in a hall in Hitchin. Nearby, there was one of Samuel’s oil paintings. This shows seven men seated around a small table listening to a man standing with his left hand on the table. The standing man is Bishop Samuel Wilberforce (1805-1873). He is addressing members of the Oxford Mission amongst whom is the novelist Lord Lytton of Knebworth (Hertfordshire). The bishop was a son of the anti-slavery activist William Wilberforce. Bishop of Winchester from 1870 until 1873, he was both against slavery and Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. Samuel Lucas’s painting depicts him when he was Bishop of Oxford, which he became in 1845, and remained until he was shifted to Winchester. The Oxford Mission was an Anglican missionary organisation, which became important in Bengal in the late 19th century.

The two pictures described relate to Samuel Lucas’s involvement of the anti-slavery movement. In 1840, he was Hitchin’s delegate to the Anti-Slavery Convention held in London at Exeter Hall on the 12th to 23rd June 1840. During this period, he and his wife hosted some of the delegates who had come from the USA. The convention is portrayed in a painting by Benjamin Haydon (1786-1846), which is now in the National Portrait Gallery. The gallery’s website has a photograph of this painting, which has been displayed so that the viewer can identify each of the people in it. Samuel Lucas can be found near the back of the gathering near a pillar.

Lucas was against slavery, as were many of his fellow Quakers. In addition to this activity, his artistic creations, and his involvement in the family business, he was also an active contributor to the life and development of Hitchin. One of the largest of his paintings in the gallery, but not included in the exhibition, is a depiction of Hitchin’s Market Place. Each of the many people shown in the painting is a portrait of an actual person. The museum has an interactive guide to identify the people. One of them was Isaac Newton (1785-1861). This gentleman was not the famous scientist but the owner of a family firm of painters, plumbers, and glaziers. One of the many folks in the picture has a dark complexion. This is a portrait of Samuel ‘Gypsy’ Draper (1781-1870). He was a violinist, who played for dances and fairs in the area in and around Hitchin for about 20 years. Some of the local Quakers disapproved of him, but Samuel Lucas placed him at the front of the crowd in the centre of the painting. Had we not visited the North Hertfordshire Museum out of pure curiosity, I doubt that we would have ever come across the life and works of Hitchin’s Samuel Lucas. We spent most of our time looking at the superb exhibition about him, so that we had hardly any time left to see the rest of the museum. A fleeting glimpse of the other galleries in the lovely modern building was enough to persuade us that we need to return to see more.

September 15, 2023

A resting dog in Calcutta

In hot midday sun

A feral canine slumbers

Let sleeping dogs lie

Read my new book about travelling in India. It is both informative and entertaining. Buy if from Amazon websites. EG:

.https://www.amazon.co.uk/HITLER-LOCK-OTHER-TALES-INDIA/dp/B0CFM5JNX5/

September 14, 2023

A tree, a composer, Midsummers Night Dream, and the Barbican in London

BURNHAM BEECHES IS an area of woodland not far from Slough and Windsor. Rich in beech trees, it was purchased by the Corporation of London in 1880. The German composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) visited Britain several times between 1829 and 1847. While staying in England, Felix enjoyed spending time in Burnham Beeches. It is said that there was one old beech tree under which the composer liked to sit. Legend has it that it was in the shade of this tree that he gained inspirations for some of his compositions including some of the well-known “Incidental music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’” (composed 1842). In January 1990, when the tree was about 500 years old, it fell over during a storm.

Part of the fallen tree was presented to the Barbican Horticultural Society. Like Burnham Beeches, the Barbican (a post WW2 development in the City of London) is managed by the Corporation of London. The remnant – part of the tree’s trunk – stands on a section of the elevated walkway not far from Barbican Underground Station. Next to it, there is a plaque detailing its history and its probable connection with the composer.

What I have described so far appears in many websites detailing the curiosities of London. However, not one of them mentions that there is yet another fragment of this tree within the barbican. This piece of the dead tree is smaller than that on the walkway, and can be found, somewhat hidden by vegetation, within the Barbican’s magnificent conservatory.

I wondered what had attracted Mendelssohn to Burnham Beeches. In an article by Helen J Read, published by the Buckingham Archaeological Society on its website (www.bucksas.org.uk), I learned that Felix was often a guest of Mr and Mrs Grote, who lived close to Burnham Beeches. They often entertained musical and literary figures. Amongst their many guests was the Swedish singer Jenny Lind, who first performed in London in 1847. The singer also had a favourite tree, which, like Mendelssohn’s, was destroyed in a storm.

Regarding Mendelssohn and his tree, Ms Read wrote:

“Mr and Mrs Grote also entertained the composer Felix Mendelssohn. His favourite part of the Beeches was a mossy slope between Grenville Walk and Victoria Drive, at that time covered with pollarded trees. Many maps mark this area as Mendelssohn’s slope, and it is thought that the music for Puck and Oberon from ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ was inspired by this area. After Mendelssohn’s untimely death, Mrs Grote erected a headstone in his memory but the headstone was removed …

… There is no specific mention in the earlier maps or guides of any particular tree favoured by the composer, but a plaque was later erected on an old pollard tree. The tree blew over and the plaque was moved to one nearby until the storm of 1987, when this tree lost all its branches.”

Judging by what Ms Read wrote, it seems to me that there is a possibility that the fragments of tree, now commemorated at the Barbican as being Mendelssohn’s Tree, might not be remnants of the one beneath which he sat. Even if these bits of timber are not from his favourite tree, they make a charming memorial to a composer whose music gives pleasure to so many people.

September 13, 2023

Art from India displayed amongst the plants

I ENJOY SEEING SCULPTURES displayed in gardens or other plant-filled locations. Until March 2024, the wonderful conservatory in London’s Barbican Centre is hosting a selection of sculptures by Ranjani Shettar. She was born in Bangalore (Bengaluru, India)) in 1977, and now lives and works in rural Karnataka. Her current exhibition in the Barbican is called “Cloud Songs on the Horizon”. The works on display were made especially for this site.

Her works are made of various materials (wood, stainless steel, muslin, and lacquer) and she employs techniques that have been adapted from traditional Indian crafts. Ms Shettar’s organic sculptures look like magnified plants or parts of plants. As she said once:

“Nature’s beauty is ever present, art helps to uncover, perceive and appreciate it.”

Seeing her exhibits in the Conservatory, certainly confirms this. However fine the artworks, putting them amongst plants helps emphasise the greater beauty of nature’s creations. The beauty of the sculptures competes with that of the plants, but the latter almost always win. So, placing one’s artworks within an area rich in plant life is a brave thing to do. I felt that Ms Shettar had done it successfully. Her creations have a harmonious relationship with the plant life surrounding them.

Whether or not you visit the exhibition, which I enjoyed, seeing the Barbican’s Conservatory – the second largest in Greater London – is always a worthwhile experience.

September 12, 2023

Why give them that name?

THERE IS A SHORT crescent lined with elegant residential houses near to the Kensington Temple church close to the centre of London’s Notting Hill Gate. A few yards west of this there is a short cul-de-sac called Horbury Mews. The crescent also bears the name Horbury. Although I have passed them often, it was only today that I wondered about ‘Horbury’.

Both the Crescent and the Mews were built on land that was leased to William Chadwick in 1848 by Felix Ladbroke, heir of the property developer and landowner James Weller Ladbroke (died 1847). William, a developer, built many houses on the Ladbroke Estate in Kensington. His heir WW Chadwick constructed the houses on Horbury Crescent between 1855 and 1857. The mews nearby bear the date 1878, which is prominently displayed on one of its buildings. The mews was constructed on a former nurseryman’s grounds. They served to house horses and servants of the nearby houses. Today, they are homes for the well-off.

The name Horbury derives from the nearby Kensington Temple, which was built in 1848-49, and was then called ‘The Horbury Chapel’. The name was chosen because the hometown one of its first deacons was Horbury in Yorkshire.

So, two street names in a little part of Kensington commemorate a small town in Yorkshire. I did not expect to discover that.

September 11, 2023

A survivor on Oxford Street near Selfridges

I HAVE PASSED IT SO many times whilst travelling by bus along London’s Oxford Street, and wondered what it is. I am referring to a well-maintained brickwork tower-like structure surmounted by a recumbent stone lion. It is a few yards east of Selfridges department store. Eighteenth century in appearance, it looks incongruous standing flush against an undistinguished modern brick building. The object of interest stands on the eastern corner of the intersection of Oxford Street and a short cul-de-sac, Stratford Place, about which I will write more in the future.

Stratford Place runs in a north/south direction. Its eastern side is lined with a row of Georgian terraced houses. Prior to the twentieth century and the development of Oxford Street as a shopping district, the row of Georgian houses would have extended south with the southernmost of them having a façade on Oxford Street. In 1890, the Georgian villa that stood on the eastern corner of Oxford Street and Stratford Place was demolished. All that remained was the lion-topped gate house (or porter’s lodge), which I have seen so often whilst travelling past on the bus. The west side of Stratford Place was demolished to build a huge Lyons Corner House eatery. The demolition included the loss of the western gatehouse that used to face the still standing one, which has been preserved.

September 10, 2023

A landmark in London’s Soho since 1949

DURING THE LATE 1950s and much of the 1960s, my mother created artworks in the sculpture workshops of St Martins School of Art, which was then located on Charing Cross Road near to Foyles bookshop. My mother was a keen follower of the recipes of Elizabeth David (1913-1992), who introduced Mediterranean food to British kitchens. Near to St Martins in Old Compton Street, there were many food shops that supplied the ingredients that were required to follow Ms David’s recipes accurately. There used to be a French greengrocer between Charing Cross Road and Greek Street. This was one of the only places where ‘exotic’ salads such as mâché (lamb’s lettuce) could be purchased. Further west along Old Compton Street, there was a Belgian butcher, Benoit Bulcke, which cut meat in the French style, which my mother preferred. She claimed that English butchers were not ‘up to scratch’. Both these shops have long since disappeared. Another Soho establishment, which we used to visit regularly, was Trattoria da Otello in Dean Street. We went there so often that we were treated like old friends. Now, sadly, that wonderful restaurant is no more.

Three Old Compton Street shops frequented by my mother are still in business. They are the Algerian Coffee Stores, whose appearance has barely changed since the early 1960s when I first remember entering it; and a supplier of Italian foods: I Camisa & Son. Lina Stores, which my mother also used to visit still exists, but its branch on Brewer Street (and other newer branches) seems to have become more like restaurants than Italian delicatessens.

During school holidays, I used to accompany my mother on trips from Golders Green, where we resided, to the West End. On most of these excursions, food shopping in Soho was on our itinerary. So, as a youngster I got to know these various food shops quite well. As an innocent child, I associated Soho with food shopping rather than its other more colourful activities.

Every visit to Soho involved a stop at Bar Italia on Frith Street. There, I would be treated with a cappuccino while my mother drank an espresso. From when I first knew it in the early 1960s (or possibly the late 1950s), the overall appearance of Bar Italia has barely changed. As a friend remarked on a recent visit, the cracked Formica counter opposite the bar is typical of how cafés would have been fitted out back in the 1950s.

Bar Italia is almost three years older than me. It was founded in late 1949 by Lou and Caterina Polledri. Lou was born in the Italian city of Piacenza. According to the Bar’s website, some of the above-mentioned Formica was put in place in 1949, when the establishment was for its time ‘state-of-the-art’. The floor is that which was laid down by members of the Polledri family in 1949.

When it opened, Soho had a large Italian community, which much appreciated the Bar Italia as a home-away-from-home. At the far end of the small establishment, there is a television that broadcasts Italian TV, mostly sporting events. Each time I visit the place, the screen sems to have been replaced by a larger one. However, I cannot recall whether there was a television in place when I visited as a child. What I do remember is that next door to Bar Italia, there used to be a Greek restaurant called Jimmy’s, which, for some reason, my mother never took us there.

Once a local for the Italian community, Bar Italia has become somewhat of a Soho landmark and tourist attraction. In addition to coffee and alcoholic drinks that would be available in any local bar in Italy, Bar Italia now also serves hot meals. It also sells Portuguese ‘natas’, which are not typical fare in bars in Italy. Apart from this change, the prices of its excellent coffee have shot up to levels higher than most London cafés charge. Whereas one can expect to pay from on average £2.80 to “£3.20” for an espresso, Bar Italia is now charging over £4.20. I mention this, but do not begrudge them because by patronising Bar Italia we are helping to preserve a delightful historical London landmark.

NOW watch this lovely little video about the place: