Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 133

March 4, 2022

A poet in Hampstead and Rome

THE SHORT-LIVED POET, John Keats (1795-1821) resided briefly in Hampstead in what is now called Keats House. In my new book, “Beneath a Wide Sky: Hampstead and its Environs” *, Keats:

“… took a great liking to Hampstead and settled there in 1817. He lived in Wentworth House, which was later renamed ‘Keats House’. The house in Keats Grove was built in about 1815 and divided in two separate dwellings. One half was occupied by Charles Armitage Brown (1787-1842), a poet and friend of Leigh Hunt and the other half by Charles Wentworth Dilke (1789–1864), a literary associate of Hunt and a visitor to his home in the Vale of Health. Keats became Brown’s lodger. This was after Keats had visited his neighbour Dilke, with whom he became acquainted following an introduction by the poet and playwright John Hamilton Reynolds (1784-1852), who was part of Leigh Hunt’s circle of friends.”

Keats remained in Hampstead until 1820, when, ailing, he left for Italy to try to improve his health. Leigh Hunt (1784-1859), who lived in Hampstead’s Vale of Health, noted in his autobiography that Keats died in Rome and was buried in the English Protestant cemetery near the monument to Gaius Cestius. Amongst his graveside mourners was the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), who also had spent time in Hampstead.

Had Keats not travelled to Italy, he would have probably died in Hampstead. If that had been the case, it would have been likely that he would have been buried in the graveyard of St John’s, Hampstead’s parish church on Church Row, where the artist John Constable rests in peace.

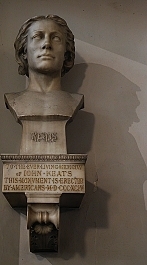

Bust of Keats in St Johns, Hampstead

Bust of Keats in St Johns, HampsteadWithin the church there is a memorial to Keats, a bust, dated 1894, within 100 years of the poet’s birth. A gift from admirers of Keats in the USA, it was the first memorial to Keats in England. The story of the bust is related on the church’s website (https://hampsteadparishchurch.org.uk/data/keats_bust.php) as follows:

“Anne Whitney, a Boston sculptor (1821-1915) carved her original bust of Keats in 1873. The marble bust was inscribed Keats and not signed. It was exhibited the same year at Doll and Richards, Boston. It was owned by the artist until 1915 when it was bequeathed to Fred Holland Day. Day exhibited it at Boston Public Library in the loan exhibition of his Keats memorabilia in 1921 to mark the centenary of the poet’s death. The Keats bust was given by Fred Holland Day to Keats House and Museum shortly before he died, and its arrival was acknowledged by Fred Edgcumbe the curator of Keats House and Museum on 2 November 1933, the day of Day’s death. The marble replica of the bust inscribed KEATS AW (monogram) 1883 was carved by Anne Whitney in 1883. It was exhibited by F. Eastman Chase, Boston, and presented by Americans, as the first memorial to Keats on English soil, to Hampstead Parish Church on 16 July 1894. The bust remained in position until March 1992 when it was stolen. It was seen by Judith Bingham, the composer, when it was about to be auctioned at Finchley in May 1992. It failed to reach its reserve, Judith Bingham recognised its identity and it was returned to the Parish Church.”

The Keats bust is near the Lady Chapel, in which I saw a remarkable painting by Donald Chisholm Towner (1903-1985), who lived in Hampstead, in Church Row from 1937 until his death. The church’s guidebook revealed:

“The Altar Piece in the chapel was painted by Donald Towner of Church Row, in memory of his mother. True to the medieval tradition Towner used a local resident as the model for Mary, his nephew for John and his own mirror image for Christ.”

What is remarkable is that the three figures are depicted standing in Church Row. St John’s church can be seen in the background.

Apart from the bust and the painting, the church is well worth visiting to see its lovely architecture and to enjoy its peaceful atmosphere.

*My book is available from Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09R2WRK92

March 3, 2022

A short street in Kensington and social differences

AUBREY WALK IS a short street in Kensington. About 260 yards in length, it leads west from Campden Hill Road. Originally, it was the approach road to Aubrey House. Until 1893, when it was given its present name, the short stretch of road was named ‘Notting Hill Grove’ (https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol37/pp87-100#h3-0006).

St George, Aubrey Walk

St George, Aubrey WalkAubrey House, at first known as ‘Notting Hill House’, was completed by the end of the 17th century. It is at the western end of the street and was attached to some springs with medicinal properties: the Kensington Wells. In the mid-18th century, the house was enlarged by its then owner, Sir Edward Lloyd. The house and its extensive grounds passed through the hands of many different owners. Between 1767 and 1788, it was the home of the diarist and political observer Lady Mary Coke (1727-1811), the daughter of the second Duke of Argyll. By the mid-19th century, it acquired its present name, Aubrey House, to commemorate Aubrey de Vere, who owned the manor of Kensington at the time of the Domesday Book.

In 1863, the house became the property of a politician and Member of Parliament Peter Alfred Taylor (1819-1891). He was a radical, a supporter of the northern states in the American Civil War, and an anti-vaccinationist. A website, british-history.ac.uk, noted:

“Peter Alfred Taylor was M.P. for Leicester from 1862 until 1884 and was a noted champion of radical causes. His wife Clementia was also famous as a philanthropist and champion of women’s rights. They were closely involved in the movement for Italian liberation and Mazzini was a frequent visitor to Aubrey House. In 1873. Taylor sold the house to William Cleverley Alexander, an art collector and patron of Whistler.”

The Taylors opened the Aubrey Institute in the grounds of the house. This was to improve the education of poor youngsters. WC Alexander (1840-1916), who bought the property, employed the artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) to decorate the walls of the reception rooms of the house. Sadly, today, all that the public can see of the house, which is now a private residential complex, are glimpses over the outer wall of the roof and the upper storey windows.

Aubrey House used to be neighboured by the now demolished Wycombe Lodge and its large garden. In its place, there is a set of recently built houses arranged around a rectangular open space. This is called Wycombe Square.

Walking east from the wall of Aubrey House, we pass several places of interest including Wycombe Square. On the south side of Aubrey Walk is the club house of Campden Hill Lawn Tennis Club. This was founded in 1884, only seven years after the first championship competition at Wimbledon. Its twelve courts, six outdoor and the others indoors, are not visible from Aubrey Walk. Almost opposite the club, numbers 38-40, a 20th century art deco style building, contains the former home of the singer Dusty Springfield (1939-1999), who resided there from 1968 to 1972.

At the eastern end of Aubrey Walk there is the distinctive Victorian gothic church of St George (Campden Hill). In the middle of the 19th century, the area between Kensington Church Street and Campden Hill Road, the area containing Uxbridge Street, Hillgate Street and Place, and other small lanes, was a slum. It was where labourers in the nearby gravel pits and brickfields lived, often with several families in one tall, narrow house. Many of the folk living in this locality were destitute, which is difficult to imagine when you look at the place today. It was decided to build a church nearby to cater for the poor people living in this deprived area. This became St George’s on Aubrey Walk. The first church was an iron building, a large hut, which had been used by soldiers as a chapel on the Crimean War battlefields.

In 1862, the Vicar of St Mary Abbots, the parish church of Kensington arranged to break up his huge parish into smaller units, one of which became the ecclesiastical district of St George. John Bennett, a local builder, financed the construction of a church to replace the iron structure. The first stone of the present church, which can accommodate 1500 people, was laid in 1864. Its architect was Enoch Keeling (1837-1886). The building he designed is a rare example of ‘continental gothic’, also known as ‘Eclectic Gothic’. This style makes use of brick and stonework of various colours, both externally and internally. Its exterior gives an Italianesque impression. This is especially the case when you look at the prominent bell tower at the southeast corner of the church.

St George’s was actively involved in providing education, and social work (including a soup kitchen on Edge Street) to its congregation who lived in the nearby slums. It also played a major role in the Temperance Society, which served Kensington, Notting Hill, and Shepherds Bush. Before WW1, services at St George’s were well-attended, and a wide range of music was played. Writing in a booklet about the church, its authors, Tom Stacey and Ivo Morshead, noted:

“Elaborate settings for the choir were juxtaposed with favourites from ‘Hymns Ancient and Modern’ … The repertoire consisted of works by Stanford, Goss, Barnby, and Handel … St George’s was hardly classy at this time but it sang the same music as its more fashionable contemporary churches … Perhaps the music was above the heads of some of the congregation; yet St George’s remained a full church until the outbreak of the 1914 War.”

By the 1890s, the people that attended services at St George’s were becoming more similar to those living in other parts of Kensington because slowly but surely housing conditions were being improved and what had been a ‘down and out’ part of Kensington was ‘coming up in the world’. Many of the former slum dwellings just east of St George’s are still standing, but instead of being the residences of the poor, they are the much sought-after homes of the wealthy.

In nearby Kensington Place, east of the church, stands the parish hall, St George’s Hall. In 1901, the Victorian building was, according to a plaque affixed above its main entrance:

“… acquired and altered to commemorate the glorious reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria born at Kensington Palace May 24: 1819”

It is now used for residential purposes.

Aubrey Walk, although short in length, has several interesting sights. In the 19th century, it linked two social extremes. At the western end was the fabulous Aubrey House and at the eastern end, the poor of Kensington flocked to attend services in St George’s Church.

March 2, 2022

John Constable and a bookseller’s grave

ST JOHN’S IS the parish church for the C of E parish of Hampstead. The present building, designed by Henry Flitcroft and John Sanderson, was dedicated in 1747. It stands on Church Row, which is lined with elegant 18th century houses and links Heath Street with Frognal.

Church Row, Hampstead, London

Church Row, Hampstead, LondonThe church is at the northern edge of a graveyard well populated with funerary monuments, including the grave of the artist John Constable (1776-1837). This grave is in the old part of the church’s cemetery, which was hardly used after 1878, when it was officially closed. A larger, newer graveyard is on a sloping plot across Church Row and north of St John’s. This is the burial place for a host of well-known people as well as the family of Hampstead’s Pearly Kings and Queens.

When I used to visit Hampstead in the 1960s and early 1970s, I used to ‘haunt’ a most wonderful second-hand bookshop on Perrins Lane, which leads east from Heath Street. It was owned by an old gentleman, whose name, Francis Norman, I only learnt many years after he died. Recently, I met a member of Mr Norman’s family. He told me that Mr Norman died in 1983 and is buried in the cemetery at St Johns, describing the location as: “by a wall near Harrison and the children’s playground”.

I was not sure to whom he was referring when he mentioned “Harrison”. At the church, we asked a lady about Mr Norman’s grave. Hearing that he had died in 1983, she suggested that we looked in the newer part of the cemetery. This has a wall that borders a children’s playground. When I looked around carefully, I found neither any monument to Harrison nor Norman’s gravestone.

On returning to the church and explaining our unsuccessful quest, the lady sent me to see another church official, who was working in an office attached to the church. This lady knew exactly where Mr Norman was buried. She took me into the older part of the cemetery and showed me the gravestones of Francis and his wife Sonia, which lie next to each other. They are next to a small wall and close to a large monument to the clockmaker John Harrison (1693-1776). He was the inventor of a marine chronometer, which solved the problem of how to ascertain longitude whilst at sea. His story can be read in “Longitude” by Davina Sobell. Norman’s grave is not far from that of John Constable.

Francis and Sonia Norman are amongst the few people buried in the old cemetery after it was closed in 1878. My helpful informant at the church did not know why they had been interred there instead of in the newer part.

Francis Norman was a kindly, wise, and friendly fellow, who did not mind me and several of my friends spending hours in his shop, often spending very little on his extremely reasonably priced books. I have fond memories of the time that we spent in his presence, which are described in my book “Beneath a Wide Sky: Hampstead and its Environs” (https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09R2WRK92). So, it was with great pleasure that I met one of his family and was able to pay my respects at his grave.

March 1, 2022

Annigoni under the flight path to Heathrow

HAYES IN THE London Borough of Hillingdon is not on the itineraries of most tourists, although many of them fly over the area when landing at nearby Heathrow Airport. In addition to the venerable old (late mediaeval) parish church of St Mary, there is a lovely park and another church worth seeing in the area.

Painting in Hayes by Pietro Annigoni

Painting in Hayes by Pietro AnnigoniSt Mary’s church stands at the northeast corner of Barra Hall Park, the grounds of Barra Hall. The park was opened to the public in 1923. Largely on level ground, it has lawns, flower beds, and plenty of old trees. There is a bandstand whose roof is supported by metal pillars with curly decorative features. Nearby, there is an open-air theatre whose stage is under four enormous rectangular metal plates, that act as shades. Each of them has been bent into a slight curve. Its auditorium consists of circular concrete steps, which can accommodate an audience of 180.

The Barra Hall, which stands within the park, was originally a manor house, once known as ‘Grove House’. In the late 18th century, it was home to Alderman Harvey Christian Combe (1752-1818), who became Lord Mayor of London in 1799. In 1871, it passed into the hands of Robert Reid, an auctioneer and surveyor. Reid claimed to be descended from the Reids of Barra. He enlarged and modified the building in various ways and renamed it Barra Hall in 1875. In 1924, the house became the Hayes and Harlington town hall. When Hayes became part of the Borough of Hillingdon, the Hall ceased being used as a town hall. In 2005, after renovation, the large house became used as a children’s centre. The building is Victorian in appearance with a mixture of neo-Jacobean and neo-gothic decorative features.

The Hall and its park are less than a mile north of the Lidl supermarket in the Botwell Green area of Hayes. Opposite the supermarket, stands the Roman Catholic church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. This basilica-style church was designed by Burles, Newton, and Partners and completed in 1961. It has a tall brick bell tower. In front of its vast west window, there is a fine statue of the Virgin by Michael Clark. This window, along with those beneath the tall ceiling above the wide nave, fills the spacious church with light. The nave is flanked by north and south aisles beneath lower ceilings. The walls of these aisles contain attractive stained-glass, both abstract compositions and depictions of biblical scenes. These windows were designed by Goddard and Gibbs. High above the altar, hanging on the east wall of the chancel, there is a lovely painting of the Virgin and Child by Pietro Annigoni (1910-1988). At the east end of the north aisle, there is a painting of St Jude by Daniel O’Connell.

Before the church was built, the local congregation of the parish, which was created in 1912. worshipped in a chapel created in Botwell House, an early 19th century building, which still stands in the grounds of the church. Both this church and the much older one near Barra Hall Park provide welcome, peaceful oases, which allow one to temporarily escape from the bustle and stresses of modern life.

Under the flight path to Heathrow

HAYES IN THE London Borough of Hillingdon is not on the itineraries of most tourists, although many of them fly over the area when landing at nearby Heathrow Airport. In addition to the venerable old (late mediaeval) parish church of St Mary, there is a lovely park and another church worth seeing in the area.

Painting in Hayes by Pietro Annigoni

Painting in Hayes by Pietro AnnigoniSt Mary’s church stands at the northeast corner of Barra Hall Park, the grounds of Barra Hall. The park was opened to the public in 1923. Largely on level ground, it has lawns, flower beds, and plenty of old trees. There is a bandstand whose roof is supported by metal pillars with curly decorative features. Nearby, there is an open-air theatre whose stage is under four enormous rectangular metal plates, that act as shades. Each of them has been bent into a slight curve. Its auditorium consists of circular concrete steps, which can accommodate an audience of 180.

The Barra Hall, which stands within the park, was originally a manor house, once known as ‘Grove House’. In the late 18th century, it was home to Alderman Harvey Christian Combe (1752-1818), who became Lord Mayor of London in 1799. In 1871, it passed into the hands of Robert Reid, an auctioneer and surveyor. Reid claimed to be descended from the Reids of Barra. He enlarged and modified the building in various ways and renamed it Barra Hall in 1875. In 1924, the house became the Hayes and Harlington town hall. When Hayes became part of the Borough of Hillingdon, the Hall ceased being used as a town hall. In 2005, after renovation, the large house became used as a children’s centre. The building is Victorian in appearance with a mixture of neo-Jacobean and neo-gothic decorative features.

The Hall and its park are less than a mile north of the Lidl supermarket in the Botwell Green area of Hayes. Opposite the supermarket, stands the Roman Catholic church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. This basilica-style church was designed by Burles, Newton, and Partners and completed in 1961. It has a tall brick bell tower. In front of its vast west window, there is a fine statue of the Virgin by Michael Clark. This window, along with those beneath the tall ceiling above the wide nave, fills the spacious church with light. The nave is flanked by north and south aisles beneath lower ceilings. The walls of these aisles contain attractive stained-glass, both abstract compositions and depictions of biblical scenes. These windows were designed by Goddard and Gibbs. High above the altar, hanging on the east wall of the chancel, there is a lovely painting of the Virgin and Child by Pietro Annigoni (1910-1988). At the east end of the north aisle, there is a painting of St Jude by Daniel O’Connell.

Before the church was built, the local congregation of the parish, which was created in 1912. worshipped in a chapel created in Botwell House, an early 19th century building, which still stands in the grounds of the church. Both this church and the much older one near Barra Hall Park provide welcome, peaceful oases, which allow one to temporarily escape from the bustle and stresses of modern life.

February 28, 2022

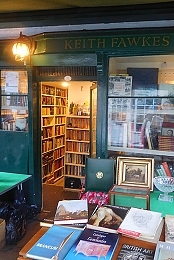

Last secondhand book dealer in Hampstead

IN THE SIXTIES, there were at least six antiquarian/second-hand bookshops in Hampstead village. Two or three of them were in Flask Walk, a quaint passageway leading northeast from Hampstead High Street. Now, there is only one in Hampstead (apart from an Oxfam bookshop), and that is Keith Fawkes’s store on Flask Walk… currently, the last of the breed.

The amiable Mr Fawkes established his shop in 1964 when there were already a few dealers of second-hand books in the village. Over the years, he has branched out into antiques and bric-a-brac whilst retaining his well-stocked bookshop. It is a treasure house of interesting books, all packed into lines of shelving separated by corridors so narrow that it is difficult for one person to squeeze past another.

Very kindly, Keith Fawkes and his bookstore manager, Sam, have agreed to display and sell a few copies of my new book about Hampstead, “Beneath a Wide Sky: Hampstead and its Environs”, which is also available from Amazon (https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09R2WRK92). While researching my book, Keith provided me with some information about another former Hampstead antiquarian bookseller, the illustrious Francis Norman, about whom I will relate more in a future post. Keith is acknowledged in my book.

So, next time that you are in Hampstead, do take a stroll along Flask Walk and look in at Keith Fawkes before having a pint in the nearby Flask pub, also mentioned in my book.

February 27, 2022

Abstract art

February 26, 2022

A magnet for modernists: Hampstead

YESTERDAY, 22nd February 2022, we saw an exhibition at the Pace Gallery in central London’s Hanover Square. The gallery stands facing a conventional sculptural depiction of William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806), created in bronze by Sir Francis Chantrey (1781-1841). I have been reading a great deal about Pitt in a wonderful, recently published biography of King George III by Andrew Roberts. What is being shown in the Pace gallery until the 12th of March 2022 is far from purely representational, as the exhibition’s title, “Creating Abstraction”, suggests.

By Barbara Hepworth

By Barbara HepworthThe exhibition contains works by seven female artists: Carla Accardi (1924-2014), Leonor Antunes (b. 1972), Yto Barrada (b. 1971), Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916-2017), Kim Lim (1936-1997), Louise Nevelson (1899-1988), and Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975). Most of these names were new to me apart from Nevelson and Hepworth. The latter interests me greatly not only because one of her sculptures is near the gallery on the southeast corner of John Lewis’s Oxford Street department store, but also because for a while she lived and worked in an area that fascinates me: Hampstead.

There are several of Hepworth’s works on display at Pace. One of them, “Two Forms”, was created in 1934. By then, she had been living and working in Hampstead for about seven years. For the first few years, she was living with her first husband, the sculptor John Skeaping, and then after 1931 with her second, the painter Ben Nicolson. In 1939, she left Hampstead.

Hepworth was not the only ‘modern artist’ living in Hampstead in the 1930s. I have described the active and highly productive artistic scene in the area in my new book “Beneath a Wide Sky: Hampstead and its Environs”. I have also explained why it was that artists like Hepworth, her contemporary Henry Moore, and many others were attracted to Hampstead between the two World Wars. Their reasons for congregating in the area differed somewhat from those of earlier artists, such as Constable and Romney, who were attracted to the place many years before. Read my book to discover why Hampstead easily rivalled Montmartre in Paris as a ‘mecca’ for artistic activity. The book is available as a paperback and a Kindle e-book from Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09R2WRK92

February 25, 2022

A Victorian gem of a church

MANY YEARS AGO, I read “The Gothic Revival” by the art historian Kenneth Clark (1903-1983). If I recall correctly, he wrote that it was likely that in Britain, the gothic style never truly died out before it came back into fashion in the 18th century. What we call ‘revival’ was merely the flaring up of the embers of the use of gothic designs, which had persisted despite the flowering of newer forms of architecture, such as neo-classicism. By the 19th century, the use of gothic motifs and structural features had fully revived, especially in the construction of churches and many other buildings, such as London’s St Pancras Station and the Prudential Building (near Chancery Lane).

Today, the 22nd of February 2022, I revisited a slightly concealed church, All Saints, in Margaret Street, which runs north of Oxford Street and parallel to it. You can see its tall, tiled spire from afar, but the church itself is set back from the street in a courtyard. Externally, with its multi-coloured patterned brickwork it is eye-catching but inside it is fantastic.

The church was established by the Ecclesiological Society, which was founded in 1839 as ‘The Cambridge Camden Society”. The group’s aim was:

“…reviving historically authentic Anglican worship through architecture.” (https://asms.uk/about/history/)

In 1841, the society:

“… announced a plan to build a ‘Model Church on a large and splendid scale’ which would embody important tenets of the Society: It must be in the Gothic style of the late 13th and early 14th centuries; It must be honestly built of solid materials; Its ornament should decorate its construction; Its artist should be ‘a single, pious and laborious artist alone, pondering deeply over his duty to do his best for the service of God’s Holy Religion’ Above all the church must be built so that the ‘Rubricks and Canons of the Church of England may be consistently observed, and the Sacraments rubrically and decently administered’.”

The architect chosen was William Butterfield (1814-1900), who specialised in the ‘gothic revival’ style. The church was built on the site of a former chapel, and within the confined space available, it was accompanied by a choir school and a clergy house. The church’s spire, 227 feet high, is taller than the towers of Westminster Abbey.

The Victorian writer and art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) was full of praise for Butterfield’s edifice in Margaret Street. He wrote about it in his “The Stones of Venice, Volume III” (published 1853), observing that it:

“…assuredly decides one question conclusively, that of our present capability of Gothic design. It is the first piece of architecture I have seen, built in modern days, which is free from all signs of timidity or incapacity. In general proportion of parts, in refinement and piquancy of mouldings, above all, in force, vitality, and grace of floral ornament, worked in a broad and masculine manner, it challenges fearless comparison with the noblest work of any time. Having done this, we may do anything; there need be no limits to our hope or our confidence; and I believe it to be possible for us, not only to equal, but far to surpass, in some respects, any Gothic yet seen in Northern countries.”

That was praise indeed.

The interior of All Saints is a riot of colour. This results from the use of stones of differing hues – some inlaid to create bold patterns and others to form images of biblical scenes, glorious stained glass, gilt work, and elaborate ironwork. This feast for the eyes must be seen to be believed. And this gem of Victorian architecture, a peaceful have and a joy to see, is merely a stone’s throw from the hustle and bustle of Oxford Circus.

February 24, 2022

Rabindranath Tagore in Hove and Hampstead

FROM HOVE TO HAMPSTEAD

THE NOBEL PRIZE winning Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was born in Calcutta (Kolkata). Raised in a culturally rich, wealthy household, he began writing poetry when he was eight years old. His family wanted him to join many of his compatriots, who travelled to England to become barristers. By becoming barristers, many Indian men were able to begin on the pathway to wealth and/or political influence both within the British colonial system, or against it.

Tagore was enrolled in a school in Brighton in 1878. Whilst there, he resided in Medina Villas in Hove. His biographers, Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson, wrote in their book (published 1996) that one of Rabindranath’s (‘Rabi’s’) nieces:

“…retained fresh memories of Rabi Kaka (Uncle Rabi) in the family house at Medina Villas, between Brighton and Hove, where he settled for several months.”

Tagore wrote:

“Our house at Hove is near the sea. 20/25 houses stand in rows and the name of the complex is Medina Villas. When I first heard that we would be living in Medina Villas, I imagined a lot, such as there are gardens, big big trees, flowers, fruits, open space and lakes etc. After coming to my place I found houses, roads, cars, horses and no sign of Villas” (http://rabitalent.blogspot.com/2017/06/rabindranath-in-england.html).

The school that Tagore attended briefly, for about two months, was in Brighton’s Ship Street, close to the town’s famous ‘Lanes’ and a few feet from the seafront. Recently, a commemorative plaque was attached to the building which housed the school and is now part of a hotel, which used to be its neighbour. The plaque named the educational establishment “Brighton Proprietary School”.

I attended a preparatory school before moving on to a high school, but until I saw the plaque in Brighton I had never heard of proprietary schools. It seems as if they were private schools that were run as businesses, rather than not-for-profit organisations. A note on the National Archives website (https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/b1c290ea-4580-4c52-962b-10c0d281ac2a) revealed:

“The school was opened on 18 July 1859 under the title of the Brighton Proprietary Grammar and Commercial School for the Sons of Tradesmen. The proprietors … each had a share in the school and were entitled to take up places there. The education given had a Protestant bias and the first headmaster was the Rev John Griffiths, formerly of Brighton College.”

Brighton Proprietary School later became the Brighton, Hove and Sussex Grammar School (www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG250324). Dutta and Robinson wrote:

“After spending a short time in a school in Brighton and Christmas with his family, he was taken away to London by a friend of his elder brother, who felt he was making little progress towards becoming a barrister. There he would stay during most of 1879, with a break to visit Devon, where his sister-in-law had taken a house, and, most probably, time spent with some cousins…”

Fast-forwarding to 1912, Tagore, by then a world-famous cultural figure, visited London. During his stay, he resided in Hampstead’s Vale of Health, as I recount in my book “Beneath a Wide Sky: Hampstead and its Environs” (available from https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09R2WRK92). Here is a brief extract from what I wrote:

“The only vehicular access to the Vale is a winding road leading downhill from East Heath Road. This lane is bordered by dense woodland and by luxuriant banks of stinging nettles in spring and summer. At the bottom of this thoroughfare, there are houses. Most of the expensive cars parked outside them suggest that the Vale is no longer a home for the impoverished. At the bottom end of the road, there two large Victorian buildings whose front doors are framed by gothic-style archways. They have the name ‘Villas on the Heath’. One of them bears a circular blue commemorative plaque, which has leafy creepers growing over it. It states:

“Rabindranath Tagore 1861-1941 Indian poet stayed here in 1912.”

I have visited the palatial Jorasanko where Tagore was brought up in Calcutta. The large (by London standards) ‘villa’ in the Vale is tiny in comparison. An article published in a Calcutta newspaper, The Telegraph, on the 13th of September 2009 reported with some accuracy:

‘In Hampstead, north London, regarded as a cultural “village” today for left-wing but arty champagne socialists, there is a plaque to Rabindranath Tagore at 3 Villas on Vale of Heath.’”

I have known about Tagore’s stay in Hampstead for a long time, but it was only during a recent visit to my wife’s relatives in Hove, that we first learned of the plaque commemorating Tagore’s brief educational experience in Brighton.