Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 130

April 3, 2022

A battle scene under the hammer

SRIRANGAPATNA (SERINGAPATNAM) IS A town on an island in the River Kaveri in the state of Karnataka in southern India. I have been there several times as it is near a holy spot (the ‘sangam’, where three streams meet) where ashes of deceased Hindus, including those of my parents-in-law, are ceremoniously deposited in the waters of the Kaveri. The town near the sangam was the capital of the realm ruled by Tipu Sultan (1750-1799). This former capital of a great ruler is full of impressive architectural reminders of his era. One of these, which I have visited at least twice, is a Summer Palace, the Daria Daulat Mahal (literally, ‘Wealth of the Sea Palace’) built for Tipu in 1784. This lovely, large pavilion in the middle of a formal garden is decorated with huge painted murals depicting various subjects. Some of them show scenes of battles in which Tipu was involved, often with his enemy the British East India Company. Filled with fascinating details, these are well worth visiting.

On the 30th of March 2022, a wonderful artwork was auctioned at Sotheby’s auction house in London’s New Bond Street. Created in 1784, it is a painting measuring 31.6 feet by 6.6 feet. It is one of three copies of a work commissioned by Tipu for the Daria Daulat pavilion. It depicts the Battle of Pollilur fought on the 10th of September 1780 between the British troops of the East India Company and the Mysore Army led by Haider Ali (c1720-1782) and his son Tipu Sultan. Writing for the Sotheby’s website (https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2022/arts-of-the-islamic-world-india-including-fine-rugs-and-carpets/the-battle-of-pollilur-india-seringapatam-early), the author and historian William Dalrymple explained:

“At Pollilur, Tipu Sultan inflicted on the East India Company the most crushing defeat the Company would ever receive, and one which nearly ended British rule in India.”

He added, referring to the British:

“Out of 86 officers, 36 were killed, 34 were wounded and taken prisoner; only 16 captured were unwounded. Baillie received a back and head wound, in addition to losing a leg. Baird received two sabre cuts on the head and a pike wound in the arm. His ADC and young cousin, James Dalrymple, received a severe back wound and “two cuts in my head”. Around two hundred prisoners were taken. Most of the rest of the force of 3,800 was annihilated.”

Of the painting being auctioned at Sotheby’s, he wrote:

“The painting extends over ten large sheets of paper, nearly thirty-two feet (978.5cm) long, and focuses in on the moment when the Company’s ammunition tumbril explodes, breaking the British square, while Tipu’s cavalry advances from left and right, “like waves of an angry sea,” according to the contemporary Mughal historian Ghulam Husain Khan. The pink-cheeked and rather effeminate-looking Company troops wait fearfully for the impact of the Mysore charge, as the gallant and thickly moustachioed Mysore lancers close in for the kill. To the right, the French commander Lally peers triumphantly through his telescope; but Haidar and Tipu look on majestically and impassively at their triumph, while Tipu, with magnificent sang-froid sniffs a single red rose as if on a pleasure outing to a garden to inspect his flowers.”

As with all other items to be auctioned at Sotheby’s, the painting was put on display to the public for several days before the auction. We were lucky to have been able to view it, as we arrived only a few minutes before the public viewing period ended. One of the technicians at the auction house let us get close to the painting so that we could examine it much better than is possible when visiting the Summer Palace at Srirangapatna. I took the opportunity to take close-up photographs of details of this incredible record of late 18th century warfare. [You can view my photographs on the following website: http://www.ipernity.com/doc/adam/album/1319222] Some of them are quite gory, including decapitated heads with blood issuing from their severed necks. Many of the British can be seen being impaled by what looked like very thin, needle-like spears. I spotted one Indian soldier being struck on his head by a bayonet wielded by a Britisher. Some of the Mysore Army soldiers brandish rifles fitted with bayonets.

The British soldiers are mainly dressed in red jackets. Their opponents are depicted wearing clothes in a variety of colours. Most of the Indian soldiers have dark-coloured eyes but, as my wife spotted, some of the British have pale coloured (blue?) eyes. Many animals appear in the picture: horses, camels, elephants, and bullocks. In addition to rifles and spears, there are other weapons in the painting including: cannon, swords of various kinds, and archery bows. Seen as a whole and in detail, the painting portrays great activity and a sense of the confusion that reigns in a battle. Whereas the British appeared to be maintaining orderly formations, their opponents can be seen making a terrifyingly massive onslaught in an apparently less organised, but ultimately successful, way.

Although words are inadequate to convey the impression made on me by this painting, I am glad that I was able to see it before it is sold. It was last exhibited for a few months in 1999 in the National Gallery of Scotland (Edinburgh), and before that for a few months in London in 1990. If it is sold to a private individual, it might not be available for public viewing again for a long time.

April 2, 2022

A back to front church

JUST TWO AND a half miles north of Heathrow Airport and one mile north of Harmondsworth lies the former village of West Drayton, formerly known simply as ‘Drayton’, now part of the London Borough of Hillingdon.

Both the mainline railway and the Grand Union Canal run through West Drayton. During the second half of the 19th century, this settlement in middle of flat agricultural land was also home to grain mills, brickworks, ropemaking, and docks connected with activities on the canal. There is still some industry in the area, but now it is mainly residential.

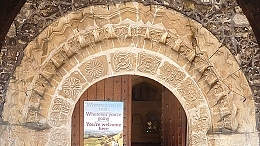

Tudor gateway and St Martins Church at West Drayton

Tudor gateway and St Martins Church at West DraytonWest Drayton’s parish church of St Martin was first mentioned in writing in 1181. The present building, with a flint covered exterior and a bell tower topped with a small cupola, mainly dates from the 15th century. Whereas most of the building is 15th century, at least one part of it, a two-arched piscina in the southeast corner, is 13th century. Currently, the church is entered through a modern doorway at the east end of the south wall instead of the older south entrance near the west end of the southern wall. On entering the church, I felt immediately disoriented. This is because, as I realised quickly, the church is arranged back to front. The high altar is at the west end of the church almost at the base of the bell tower and the pews face in that direction. Some years ago, the altar was moved from the chancel, where it had been for many centuries, to the western end of the nave. The reason for this, the vicar and her husband told me, was that it was done so that nobody in the congregation would have a restricted view of the altar during services. However, the attractively carved 15th century stone font stands where it was before the position of the altar was reversed: in the southwest corner of the nave. Another curiosity in the church is the hanging pyx suspended above the high altar. This gothic revival style container (based on the appearance of a mediaeval pyx in a church in Suffolk), which holds the sacrament and can be lowered during services, was designed by Andrew Low, manufactured at Pinewood (film) Studios, and placed in St Martins in 1975.

This oddly arranged church contains several carved stone memorials on its interior walls. Many of them commemorate members of the De Burgh family. Their bodies and those of the Paget family are sealed in a vault below what was originally the chancel.

With only a brief interruption during the 17th century, the manor and estate of West Drayton was owned by the Paget family between 1546 and 1786. In 1786, Henry Paget (1744–1812), 1st Earl of Uxbridge, sold the manor to a London merchant Fysh Coppinger (died 1800), who changed his surname to De Burgh, that of his wife. His memorial is in the church. Henry Paget’s eldest son, Henry William Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey (1768-1854), lost his right leg during the Battle of Waterloo (1815). It was replaced by a wooden prosthesis. His amputated leg was buried in Belgium, whereas the rest of his body was interred in Lichfield Cathedral.

The church and its small cemetery are enclosed within an old wall with Tudor brickwork. This is part of a large wall, which once enclosed private grounds. Following the passing of an Act of Parliament, Sir William Paget (1506-1563), at one time secretary to Jane Seymour (c1508-1537), one of the wives of King Henry VIII, enclosed his grounds with a brick wall in the 1550s. The Act stipulated free public access to the church. Parts of this wall can be seen around the churchyard and alongside Church Road. The Paget family built a mansion on the land that had been enclosed. This building, West Drayton Manor House, was demolished in 1750 by the then Earl of Uxbridge. Although the spacious brick mansion, where the Paget family once lived, is no longer, the red brick gatehouse to the grounds still stands. According to Bob Speel (www.speel.me.uk), this Tudor grand entrance with two octagonal turrets was built in the 16th century. Close to the old gatehouse, there is a newish housing estate, a small enclave called Beaudesert Mews, which was built on land on which at least a part of the long-since demolished manor house might have stood. The name ‘Beaudesert’ relates to the above-mentioned Sir William Paget, who had the title ‘1st Baron Paget de Beaudesert’.

By the 19th century, the De Burgh family were living in Drayton Hall, an early 19th century building, which now serves as Council Offices and is surrounded by Drayton Park, near the church. A new building attached to it contains offices of at least one commercial enterprise. West Drayton retains a rectangular grassy space, The Green, once the village green. Several of the buildings around it look as if they were present well before the area was engulfed by London’s western spread. Unlike nearby Harmondsworth and Longford, West Drayton is not under threat of suffering demolition if or when Heathrow Airport is expanded.

April 1, 2022

Just around the corner … in South Kensington

PEOPLE USUALLY ASSOCIATE South Kensington with its magnificent set of museums. However, there is far more than that in the district, and within a few yards of the museums. Here are a few places of interest near to the Victoria and Albert Museum (the ‘V&A’).

The V&A stands on the northeast corner of Exhibition Road and Cromwell Gardens (a short stretch of the A4) and faces the Ismaili Centre on the southeast corner. This attractive building built for the religious community that is led by the Aga Khan was designed by the Casson Conder Partnership and completed in 1985. According to the website of the Ismailis, https://the.ismaili, the building’s pleasing exterior:

“… has used materials and colours which are compatible with those of the surrounding buildings while at the same time in keeping with the traditional Islamic idiom and its colours of whites, light greys and blues.”

Monument in he Yalta Memorial Garden

Monument in he Yalta Memorial GardenAn open space, The Yalta Memorial Garden, on the east side of the centre contains a monument to remember “… the countless men, women, and children, from the Soviet Union and other East European states, who were imprisoned and died at the hands of Communist governments after being repatriated at the conclusion of the Second World War…” The memorial consists of a column on the top of which there is a sculpture by Angela Conner (born 1935) depicting 12 faces of men, women, and children. Nearby, a house on the northeast corner of Thurloe Square and facing the V&A, bears a plaque informing that the museum’s first Director Henry Cole (1808-1882) lived there.

The Brompton Oratory, or to give its full name, the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, is a huge Roman Catholic church with a neoclassical façade and a dome. It stands east of the V&A. It was designed by the architect Herbert Gribble (1846-1894), a convert to Roman Catholicism, and constructed between 1880 and 1884. The architectural style is mainly Roman Baroque. This enormous edifice was the largest Roman Catholic church in London until Westminster Cathedral was constructed in the first decade of the 20th century.

Cottage Place runs along the east side of the Oratory towards the Holy Trinity Brompton church north of it. A building that looks like many of the older Underground station entrances on the Place has a façade decorated with blood-red glazed terracotta tiles. Between 1906 and 1934, when it was closed, it was the entrance to Brompton Road station on the Piccadilly Line. It was a stop between the still functioning Knightsbridge and South Kensington stations. It was closed because it was hardly ever used by passengers. An article in the Guardian newspaper, published in February 2014, related that during WW2, the disused station was used as a command centre for anti-aircraft batteries. It also suggested that the Nazi Rudolf Hess (1894-1987) was interrogated here. Between the station’s closure and about 2014, the building was owned and used by the Ministry of Defence.

The Holy Trinity Brompton Church, a gothic revival structure, was designed by Thomas Leverton Donaldson (1795-1885), and completed in 1829. It was established to accommodate the growing population of this part of Kensington, which until then had to worship in the church of St Mary Abbots in Kensington, almost one mile away. In 1852, a part of the church’s land was sold for building the Oratory upon it. The large grassy space north of Holy Trinity, now a park, was formerly the church’s graveyard.

Although none of the places I have described rival the splendour of the V&A and especially its fantastic collection of artefacts, they are worth exploring if you happen to be in the neighbourhood. A problem in London is that there are so many places of the greatest interests to visitors, which often means they have so little time to explore the lesser-known curiosities that form part of the rich tapestry of London’s past and present.

March 31, 2022

Return to the Himalayas

SOUTHALL LIES NOT far from Heathrow Airport. Despite its architecture being mostly typical of dull London suburbs that developed between the two World Wars, it is far from being a run-of-the mill west London suburb. Recently, in March 2022, we visited Southall after several years since we last went there.

The centre of what was once the tiny village of Southall is about 1.7 miles north of Osterley Park house. The manor of Southall was owned by the Archbishop of Canterbury in the 14th century. Separated by countryside from its neighbours, it lay on the road from London to Uxbridge and Oxford. It was only in the 1870s that the village began expanding southwards to the Great Western Railway line. Today, the place has been fully incorporated into London and retains little or nothing of its former rustic nature.

Detail of the roof of the Himalaya Palace in Southall

Detail of the roof of the Himalaya Palace in SouthallOn arriving by train at Southall station, the observant traveller will notice that the station name signs are bilingual; they are in both Latin and Punjabi scripts. Southall is sometimes aptly referred to as ‘Chota Punjab’ (Little Punjab). The three Punjabi brothers, Charan Singh Bilga, Jagar Singh Bilga, and Lave Singh Bilga, began living in Southall in 1938. They were followed by Pritam Singh Sangha, who opened a shop in Southall in 1954, having arrived in the area in 1951. His shop was then the only shop in west London, if not in the whole of the metropolis, purveying Indian provisions. Pritam Singh Sangha in partnership with his friend and business associate, Jarnail Singh Hura (also known as “Ghura”), established the first known business in Southall and Fakir Singh purchased numerous houses which he rented out to his countrymen.”

Vivek Chaudhary, writing in the Guardian in April 2018, recorded:

“By the time my own father arrived in 1960, local authority records show that there were approximately 1,000 Punjabis living in Southall, nearly all men. He would joke that one of the reasons why they settled here was because of its proximity to Heathrow airport, only three miles away, and “if the gooras [whites] ever kicked us out, it would be easy to get on a plane and return home”. It was a light-hearted reference to the uncertainty that was generated by the chronic racism of the time. It was the R Woolf rubber factory in neighbouring Hayes that attracted Punjabis to Southall – the general manager had served with Sikh soldiers during the second world war and was only too happy to recruit them…”

He added:

“Punjab was partitioned by the British in 1947; part of it fell within Pakistan with the remainder in India. Punjabis can be Sikh, Hindu or Muslim, and while all three demographics settled in this outpost of west London, it was the Sikhs who came in the largest numbers and gave Southall its distinct identity.”

Chaudhary mentioned that at the time he wrote his article, although at one stage Southall’s population was 70% Punjabi, this has decreased to about 50% and the descendants of many of the original settlers:

“…have prospered and moved to wealthier pastures, replaced by new communities from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Somalia. At its heart, though, this corner of west London remains an indelibly Punjabi town.”

And so, it is. Southall is like the Punjab and other places in India or Pakistan, but with the often-dull English weather and rather pedestrian suburban architecture. The main streets, South Road and the Broadway (Uxbridge Road), are lined with shops, small bazaars consisting of several tiny shops, and eateries. Judging by the profusion of colourful, often glittering, Indian (and Pakistani) style party clothing on sale, one might be excused for thinking that the people of Southall do nothing apart from attending ‘glitzy’ weddings. If you wish to sample shopping as it is in India without leaving the country, then Southall is the place to do it in London. It seemed to my wife and me that the quality of the clothing on sale was high, better than much that is available in India. A Sikh salesman explained that what is on sale in Southall is made in India but unlike what is on sale over there, this is export quality.

One building is worthy of special mention in Southall, apart from the area’s gold-coloured domed Sikh gurdwaras. This is the former Himalaya Palace cinema. Built in 1929, it is unique in Britain in that its façade is in the form of a Chinese Temple. It has a pagoda roof which is flanked by dragons. It used to screen films from India’s Bollywood studios until it closed in 2010. It has now become an indoor market called Palace Shopping Centre. Fortunately, the building is protected by a preservation order and the façade is likely to remain a wonderful landmark in the foreseeable future. Not far away in a less distinguished building is another mall, the Himalaya Shopping Centre. Entering these malls, and the others in Southall, is like stepping into a typical indoor shopping bazaar anywhere in India. The air in these Southall shopping centres has the special fragrantly perfumed odour I associate with India.

Near the former cinema, stands the former Southall Town Hall, which was constructed in 1898. On its wall, there are commemorative three plaques placed by an anti-racism group called Southall Resists 40. They are dedicated to Gurdip Singh Chaggar, who was killed in 1976; Blair Peach who was killed in 1979; and ‘Misty in Roots & People Unite Musicians Cooperative’. Each of the three bears the words “Unity against Racism”.

March 30, 2022

An experiment in modern living

HERE ARE TWO brief extracts from my new book about Hampstead. They are from the chapter about the ‘modern artists’ who lived in Hampstead between the two World Wars and, also, the Lawn Road Flats, the Isokon, a revolutionary block of flats, built in the 1930s. The extracts are as follows:

Extract 1

“… the painter Paul Nash (1889-1946) lived at number 3 Eldon Grove between 1936 and 1939. Close by at 60 Parkhill Road the artist Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) lived and worked between 1938 and 1941. Prior to moving to Parkhill Road, Mondrian had lived with a remarkable engineer and furniture entrepreneur Jack Pritchard (1899-1992).

Jack and his family lived at 37 Belsize Park Gardens, having moved there from Platts Lane. Pritchard, who studied engineering and economics at the University of Cambridge, joined Venesta, a company that specialised in plywood goods. It was after this that he began to promote Modernist design. In 1929, he and the Canadian architect Wells Coates (1895-1958) formed the company, Isokon, whose aim was to build Modernist style residential accommodation. Pritchard and his wife, a psychiatrist, Molly (1900-1985), commissioned Coates to build a block of flats in Lawn Road on a site that they owned. Its design was to be based on the then revolutionary new communal housing projects that they had visited in Germany, including at the influential Bauhaus in Dessau. The resulting Lawn Road Flats are close to both Fleet Road and the Mall Studios in Parkhill Road. Completed in 1934, they were, noted the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘… a milestone in the introduction of the modern idiom to London’ …”

Extract 2

“… T F T Baker, Diane K Bolton and Patricia E C Croot, writing in “A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 9, Hampstead, Paddington”, noted that the Lawn Road Flats were built partly to house artistic refugees, who had fled from parts of Europe then oppressed by dictators, notably by Adolf Hitler. Some of them had been associated with the Bauhaus. These included the architect and furniture designer Marcel Breuer, the architect Walter Gropius (1883-1969), and the artist and photographer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946). All three are regarded as masters of 20th century visual arts.

Despite both having come from bourgeois backgrounds, the Pritchards aimed to free themselves from middle-class conventions. The concept and realisation of the Lawn Road Flats were important landmarks in their quest to achieve a new, alternative way of living. The atmosphere that prevailed in the community that either lived in, or frequented, the Lawn Road Flats and its Isobar was predominantly left-wing, and extremely welcoming to cultural refugees from Nazi Germany. Probably, it had not been anticipated that the place would become a convenient place for Stalin’s Soviet spies to use as a base. According to a small booklet about the flats, “Isokon The Story of a New Vision of Urban Living”, published in 2016, the flats were home to the following espionage agents …”

“BENEATH A WIDE SKY: HAMPSTEAD AND ITS ENVIRONS” by Adam Yamey is available from Amazon (https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09R2WRK92), bookdepository.com (https://www.bookdepository.com/BENEATH-WIDE-SKY-HAMPSTEAD-ITS-ENVIRONS-2022-Adam-Yamey/9798407539520), and on Kindle.

March 29, 2022

The blind beggar and his dog

AN ELIZABETH AND AN ELISABETH figured in my mother’s life during my childhood years. One was the cookery writer Elizabeth David (1913-1992), whose recipes my mother followed faithfully. The other was the sculptor Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993). Although she never met the cookery writer, she was a good friend of the sculptor. Between 1954 and 1962, Frink taught sculpture at St Martins School of Art, which was then located in Charing Cross Road. During that period, my mother, a sculptor, worked in the sculpture workshops in St Martins. It was probably then that she and Elisabeth became friends. ‘Liz Frink’, as we knew her, visited our home in Hampstead Garden Suburb as a dinner guest regularly and I remember meeting her on these occasions. My memory of these meetings was revived when visiting London’s East End this month (March 2022).

We were walking eastwards along Roman Road from Globe Road towards the Regents Canal when we passed the Cranbrook Estate, a collection of six rather bleak looking blocks of flats. The buildings are arranged around Mace Street, which is in the form of a figure of eight. The estate was built on land which had formerly accommodated a factory, workshops, and terraced houses. The blocks were completed by 1963. They were designed by Douglas Bailey and Berthold Lubetkin (1901-1990). Born in Georgia (Russian Empire), Lubetkin lived in Russia during and after the 1917 Revolution. He studied in Moscow and Leningrad (now St Petersburg), where he became influenced by Constructivist architectural principles. In the 1920s, he practised architecture in Paris, and by 1931, he had emigrated from the USSR to Great Britain, where he mixed with the artistic community then based in Hampstead (see my book: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09R2WRK92). In London, he founded Tecton, an architectural practice. He is particularly well known for his Penguin Pool at London Zoo and his luxurious block of flats in Highgate: High Point. The flats he designed on the Cranbrook Estate were for social housing.

Various other buildings and features have been added to the estate. One of these is a triangular garden surrounded on two sides by rows of single storey houses (bungalows for the elderly). In the middle of this, the Tate Garden, there is a pond with a fountain. Perched on what looks a bit like a diving board made of concrete discs piled one above another, there is a sculpture of a man and a dog. As soon as I saw this, I was reminded of Elisabeth Frink’s sculptures. Later, when I investigated it, I discovered that it is a sculpture by her. Entitled “Blind Beggar and his Dog” and cast in bronze, Liz Frink created this in 1958, which was when she and my mother must have already become friends. A sculpture depicting the Blind Beggar and His Dog, who figure in a tale that gained popularity in Tudor times, was commissioned in 1957 by Bethnal Green Council. Incidentally, there is a Blind Beggar pub in Whitechapel Road, where in 1966, the gangster Ronnie Kray shot dead a member of a rival gang, George Cornell.

We had visited the area near the Cranbrook Estate to see a small exhibition. As it had not taken long to view it and it was a warm sunny day, we took the opportunity to roam around the area. Had we not done that, I doubt that I would have become aware of this sculpture by an old friend of my mother.

March 28, 2022

Dwellings in Globe Town

ROMAN ROAD IN east London is a section of a road running northeast from Shoreditch. It is part of a Roman road, once known as ‘Pye Road’, which ran from London to Venta Icenorum that was near Norwich. The modern road passes through an area known as Globe Town, which lies just east of Bethnal Green Underground Station. Known as ‘Eastfields’ until the start of the 19th century, the area was then called Globe Town, probably because there was a pub with that name in the area. The area was developed in the late 18th century to accommodate French Huguenot and Irish silk weavers. The weavers had looms in their homes.

By the late 19th century, Globe Town had become an overcrowded slum. Then, there were not only weavers in this run-down district but also dockworkers and people considered to be disreputable: thieves, prostitutes, and vagrants.

At the start of the 20th century, some of the slum buildings were replaced by improved habitations. Some of these can be seen whilst walking along Globe Road, which runs north from Roman Road. The buildings along Globe Road were mainly constructed by the East End Dwellings Company (‘EEDC’) between 1900 and 1906. This philanthropic company was founded in 1882 to create model dwellings. One of its founding fathers was the vicar of St Judes Church in Whitechapel, Samuel Augustus Barnett (1844-1913). Samuel and his wife Henrietta Barnett (1851-1936) unwittingly played an important role in my childhood and early adulthood. For, it was their idea to create the Hampstead Garden Suburb (in north London), where I lived for almost 30 years. Interestingly, the Anglican church in the Suburb is also dedicated to St Jude.

The aim of the EEDC was to house the poor economically, yet not without making some modest profit. The company’s first project was Katharine Buildings in Aldgate, which were opened in 1885. The buildings in Globe Road were completed between 1900 and 1906 and are still in use. Apart from the EEDC buildings, Globe Road offers the visitor a few other treats. One of these is The Camel pub, whose menu includes a range of pies. Nearby is another pub, The Florist Arms, which offers stone-baked pizzas. If these food items are not to your taste, The Full Monty Café offers tasty snacks, Opposite the latter, there is a small second-hand bookshop, which raises money for a Buddhist organisation. The London Buddhist Centre is housed on the corner of Globe and Roman Roads. A short distance east of Globe Road, Roman Road crosses the Regents Canal, which is flanked on its east side by pleasant parks.

March 27, 2022

Threatened by Heathrow Airport

THE PARISH CHURCH of Harmondsworth is about 1.7 miles northwest of Heathrow Airport’s Terminal 1, yet it feels as if it were much further from it, maybe in the heart of the countryside. What was once a small village in rural Middlesex has now been engulfed by London’s westward spread. However, the old village green retains a certain rustic charm.

The name of the place derives from the name of a person, ‘Hermode’ or ‘Harmond’ and the Anglo-Saxon word ‘worth’ meaning a farm or enclosure. Set in what was once fertile farmland that provided corn and green crops for the London markets, it is now a mainly residential area. Writing in 1876 in his “Handbook to the Environs of London”, James Thorne remarked:

“The village of Harmondsworth is small and not remarkable …”

Writing 146 years later, I must disagree. The place is remarkable for retaining some of its rural atmosphere. The village green is surrounded by a row of picturesque old cottages, a slightly newer-looking village store (Gable Stores), and two pubs (The Crown and The Five Bells [formerly ‘The Sun’]), and the entrance to the churchyard of the parish church of St Mary.

The vicar of St Mary kindly unlocked the church for us. According to a history of the church by Douglas M Rust, it is probably located near the site of a pagan place of worship on one of the quintarial lines defined by Roman surveyors’ landmarks. The archaeologist Montagu Sharpe, writing in volume 33 of the “English Historical Review”, published in 1918, observed:

“Two curious discoveries came to light after the quintarial cross-lines had been drawn, making each pagus appear like a gigantic chequer-board. The first was, that 47 out of 56 mother churches of parishes in Middlesex were situated upon one or other of these lines, the apparent explanation being that Romano-British chapels (compita) adjoined the principal rural ways, which were designed to follow the quintarial lines. In the next age these little edifices were adopted by missionaries for Christian worship, following the astute and well-known direction of Pope Gregory to utilize the pagan sacra where the people had been accustomed to assemble. If so, then such sites have been associated with public worship, first pagan, then Christian, for nearly 2,000 years.”

Be that as it may, the present parish church in Harmondsworth was constructed from the 12th century onwards, much of it before the 16th century. In the 18th century, a cupola was added to the bell tower. In the following century, repairs and restoration was undertaken. The south entrance has a decorated carved stone Norman archway. The carved capitals of the pillars on the south side of the nave are 12th century. The westernmost pillars on the north side of the nave are 13th century, whereas the four pillars to the east of these are 16th century. The chancel, which is supported by the newer pillars was constructed later than the nave. Where the newer part was joined to the older, there is a discontinuity in the stonework of the arch that joins the nave to the chancel: the two halves of the arch do not match each other. The pointed arches along the north side of the nave are Perpendicular gothic in style, whereas those north of the chancel are a Tudor design.

The tower of the flint covered church used to be the tallest building in Harmondsworth until the control tower at nearby Heathrow Airport was constructed, Douglas Dark mentioned of the church:

“Little did the early builders realise that their church was later to become the parish church of the manor where many visitors to Britain first arrive.”

A few yards northwest of the church, there is another treat awaiting visitors to Harmondsworth. This is the Harmondsworth Barn, which was constructed 1425-27 on land bought in 1391 by William of Wykeham (c 1320-1404), Bishop of Winchester, to endow Winchester College. It is now maintained by English Heritage, from whose website I gleaned the following information:

“Used mainly to store cereal crops before threshing, it remained in agricultural use until the 1970s. At 58 metres (192 ft) long and 11.4 metres (37 ft 6 in) wide, the barn is one of the largest ever known to have been built in the British Isles, and the largest intact medieval timber-framed barn in England.”

The barn’s main purpose was to store locally grown cereals (e.g., wheat, barley, and oats) and was still in use during the 1970s. Its interior is a fine example of well-preserved mediaeval carpentry. The barn is located on the eastern edge of what was once Manor Farm, through which a stream of the River Colne flowed. The erstwhile farm covered the probable site of a long-since demolished Benedictine Priory.

James Thorne noted that the barn had once been ‘L’ shaped, rather than rectangular as it is today. The part of it that had made it shaped like an ‘L’ was taken away and relocated elsewhere. To quote Thorne:

“This wing was taken down about the same time as the Manor House and rebuilt at Heath Row, 1 ½ miles S.E. of Harmondsworth church. This, which is known as the Tithe Barn, exactly resembles the Manor Barn in structure, except the walls are of brick…”

Well, ‘Heath Row’ is now ‘Heathrow’ and this fragment removed from the barn at Harmondsworth no longer exists. I located it on a map surveyed in 1862. It then stood on a road or lane that ran south from the Bath Road to Perry Oaks Farm on the western edge of Heathrow village. This land is now covered by the airport terminals (1,2, and 3).

Harmondsworth village has a few other old buildings apart from those already mentioned. One of them is Harmondsworth Hall, which Wendy Tibbits described in her blog (www.wendytibbitts.info) as follows:

“This grand-sounding building was built in the early 1700s, but still has elements of a fire-damaged Tudor building which was on this site. The central chimney and a fireplace are remnants of the former hous. … In 1910 this house was the first house in Harmondsworth to have its own electricity supply.”

Both Ms Tibbits and the vicar of the parish church fear for the future of Harmondsworth should plans to extend Heathrow Airport are carried out. Most of the old village will be demolished, leaving the church and the barn. Ms Tibbits noted:

“If the London Airport Expansion plans go ahead eleven listed buildings in Longford, and twelve in Harmondsworth will be demolished, along with hundreds of other homes. Only Harmondsworth medieval Great Barn and its Norman church will survive the destruction, but who will want to visit them when they will be meters from the airport’s perimeter fence?”

Although extending the airport might benefit the country, it would be sad to lose yet more of Britain’s heritage.

March 26, 2022

Sun, shadow, and telling time

March 25, 2022

Czech it out

JAN GARRIGUE MASARYK was born in Prague (Czechoslovakia) in 1886. Son of the first President of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850-1937), Jan was Foreign Minister of his country between 1940 and 1948, when two things happened. First, the Communists began tightening their grip on Czechoslovakia and possibly connected with that, Jan Masaryk was found dead in his pyjamas in the courtyard of the Foreign Ministry in Prague on the 10th of March. By 1948, Prague already had a reputation for defenestration. Whether or not Jan was pushed out of a window remains uncertain. Two years earlier, a large non-descript house in Hampstead’s West End Lane became home to the recently formed National House, a meeting place for Czechoslovaks (mainly war veterans) in London. Now, it is known as Bohemia House. Its website (https://bohemiahouse.london/beginning-of-national-house/) explains:

“After communist revolution in 1948 and the USSR invasion to Czechoslovakia in 1968, providing the homely atmosphere as well as traditional cuisine. Converted into public house in mid 80’s, the National House serves also as a traditional restaurant showcasing Czech & Slovak cuisines to the public.”

It was in the 1980s that I first began visiting the place to sample Czechoslovak food and drink. After many years, I revisited the place recently (in March 2022).

If it were not for the sign advertising Pilsner Urquell beer projecting above a tall privet hedge, most passers-by would hardly notice that they were passing what is now a bar and restaurant. Immediately after entering via the front door, I noticed several commemorative plaques. One of them honours the British historian RW Seton-Watson (1879-1951), who fought for the rights of the Czechs and Slovaks and other subject people/nations of the former Austro-Hungarian Empireafter WW1. Next to that, there is a large metal plate remembering the Czechoslovak “soldiers, airmen, and patriots”, who fell in WW2. It makes special mention of the Czechoslovak men who flew from Leamington Spa and were parachuted into their Nazi-occupied country to assassinate Heydrich (see https://adam-yamey-writes.com/2021/11/25/leamington-spa-heydrich-and-the-tragedy-at-lidice/).

A doorway from the hallway leads into a front room used as a formal dining room. This is decorated in a mildly baroque style. A gold-framed portrait of TG Masaryk faces the door. Various other framed portraits including one of Queen Elizabeth II hang on the walls. A metal bust of TG Masaryk stands on a mantlepiece next to a credit card machine and a metal sculpture of a Czech airman and there is an old-fashioned gramophone with an LP on its turntable between the two metal sculptures. The formal dining room is separated by a folding screen from a much larger room behind it. The latter, with tables and chairs, a pool table, and a table-football unit, is a less formal space, which I do not remember from the 1980s. In those days, food was served to ‘outsiders’ in the formal front room.

The larger, rear room with windows overlooking the back garden has several interesting objects on its walls. A sombre-looking metal plate covered with many names lists those who “gave their lives for Freedom” between 1939 and 1945. On the wall facing this, there are two posters with photographs of Alexander Dubček (1921-1992), a Slovak Communist politician, who tried to reform the Communist government during the Prague Spring of 1968, which ended after a few months when the Soviet Army invaded his country. On a wall behind the table-football unit, there are two large, colourful, framed maps. One is of the Czech Republic and the other of the Slovak Republic. Between the end of WW1 and 1993, the two now independent countries were parts of one country: the former Czechoslovakia.

A visit to the toilet involves climbing the stairs to the first floor. After ascending the first flight of stairs, the next short flight approaches a huge painting depicting TG Masaryk dressed in a flowing light beige coat and sporting a straw hat with a black ribbon tied above its rim.

Today, Bohemia House continues to welcome guests, both from the lands, which were once Czechoslovakia, as well as others. Its bar offers a range of beers, spirits, wines, and soft drinks, from that region of Central Europe. I sampled a can of Kofola, a carbonated Czech soft drink, whose taste vaguely resembles Coca Cola. The pint of Pilsner Urquell beer was more enjoyable. We also tried a variety of dishes typically cooked in the Czech and Slovak republics. They were enjoyable enough, but I prefer the cuisines of both Poland and Hungary. However, do not let this comment put you off paying a visit to Bohemia House, where you will receive a warm welcome from its charming staff. And … if you wish to know more about Hampstead’s Czechoslovak, other Central European, and Soviet historical associations, you could do no better than to read my new book about the area, available from Amazon [https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09R2WRK92] and bookdepository.com [https://www.bookdepository.com/BENEAT...]).