Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 189

April 12, 2012

No. 6: Another Navy CO defenestrated

This one

was the captain commanding the Navy's Northeastern U.S. health services. The

issue was command climate. That makes 6 for the year, according to the official

scorekeeper.

April 11, 2012

The key but under-acknowledged role of foreign military advisors in U.S. history

On the train from Exeter to London the other day I was

re-reading retired Lt. Gen. Dave Richard Palmer's

Summons

of the Trumpet, partly because I decided I didn't really get it the

first time around when I read it a couple of years ago. I also picked it up

again because it as close as I think anyone has come to writing an operational

history of the Vietnam War.

The book is good, but a bit dated in places. I think General Palmer

is over-optimistic about the implications of the Ia Drang fight. He also seems

credulous about the Gulf of Tonkin incident, especially in his interpretation

that Hanoi was foolish to launch such an attack.

That said, overall I think it is the best book I've been

able to find for an overview of what actually happened in the war, rather than

what people were saying about it.

This is what Palmer writes about the important role foreign

military advisors played in the creation of these United States of America (pp.

27-28). They might be appreciated by anyone trying to advise Afghan forces

nowadays:

"There was once a time when the American army needed foreign

advisors. . . Having neither a nucleus

of professionals nor a backstop of military tradition to draw on, Congress

turned with scant hope to Europe for trained officers. They came. Lafayette,

Steuben, Kosciusko, Dekalb, Pulaski, Duportail -- just to mention a few of the

better known names is to evoke an image of the vitally important role they

played in the winning of our War of Independence.

These advisors tackled an awesome task: molding an army from

raw material in a backward country in the midst of war. A strange and often

inhospitable environment seriously complicated their job, not to mention

problems created by the barriers of language and other cultural differences.

Then, too, buffeted by puzzling and sometimes petty crosscurrents of political

and personal jealousies, . . . the foreigners often suffered acute frustration

and actual bitterness. Nonetheless, they persevered.

. . . Another unchanging reality of advising is the more

or less constant cocoon of frustration enveloping the advisor. Adjusting to

advising is a greater individual challenge than can be easily imagined by

anyone who has not done it.

Britain facing Germany in May 1940: One modern version of the Melian dialogue

By "Jeff"

Best Defense guest historian

I fully appreciate the dialogue between the

Athenian elite and the Melian elite. I am sure that among the Melians

there must have been contention as to what choice to make. In

400 BC, as in our time, an elite in the name of the people always makes such

decisions for better or worse.

A

modern parallel existed in May of 1940 in Great Britain. With her armies

being shattered on the continent and her key ally in the final stages of her

death throes, Britain faced a choice very much like that of Melos.

The

choice was no less stark than that faced by Melos. The enemy was a great power,

with the momentum of victory behind it. It was utterly ruthless. Britain

could have cut a deal with the looming threat -- a deal eagerly sought by Hitler -- and

opted out of harm's way with little loss but of reputation and

humiliation.

Many

of the British elite who were led by Halifax and the Foreign Office were

looking for such a peace treaty but Winston Churchill, understanding the nature of his foe, outmaneuvered the Halifax faction and accepted the

challenge from Hitler come what may. This choice amounted to the key

strategic decision of the 20th century. Churchill's leadership resulted in a

decision that showed a willingness to risk all to preserve western civilization

from Nazi barbarism.

This

choice in my view was anchored in realism. Churchill and his

Parliamentary allies possessed a hardboiled realism that fully appreciated the

consequences of defeat but also the possibilities (as remote as

they seemed at the time) of victory in the end.

Halifax's

approach, in contrast, was seemingly realistic on the surface but in fact was not, because it failed to appreciate the nature of the opponent. Any deal

arranged with the Nazis could only be temporary, because of the innate

predatory nature of the Nazi regime and its cold-blooded ideology.

Churchill, a historian, intuitively understood this important fact.

I

find this parallel with the experience of the Melians very compelling. Had the

Melians had a great power ally (Sparta), perhaps their choice may have become

heroically successful rather than heroically doomed. As it was there was

no deliverer off in the distance whose interests were served by a living Melos.

"Jeff" is an amateur military historian and f

inancial executive retired after

thirty years with Merrill Lynch.

Tom files for e-mail bankruptcy

I'm going to declare what a friend of mine at the Pentagon

calls "e-mail bankruptcy." As I blimblammed around Cornwall, hiking with my family

and having Proper Job ale with fried cod at night, about 2,000 e-mails piled

up. I have tried try to read anything that looked important, but if there is

something you wrote to me that has gone mysteriously unanswered, you might want

to ping me again.

If you are in Cornwall, by the way, try to catch the Motown Pirates, kind of a Cornish version

of the Commitments. The male lead singer does a terrific Marvin Gaye.

April 10, 2012

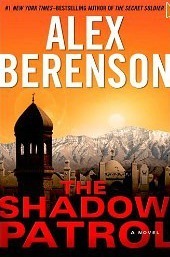

Berenson's 'The Shadow Patrol': A review

I read most of Alex Berenson's 'The Shadow Patrol' on a

flight from Philadelphia to Manchester, England, across the Atlantic Sea.

It's the first "post-Osama" novel I've read, which gave it

an extra fillip. He occasionally gets military stuff slightly wrong, which was

a slight distraction.

Here are some of the lines I liked:

--"Terror and boredom, the twin poles of infantry duty."

Yes, a familiar thought, but expressed quite succinctly here.

--The CIA view of the world. "We killed Osama. And no

civilian casualties in the op. Not one. Ten years since 9/11 and no real

attacks on American soil. Not even jerks with AKs lighting up a mall. We've

kept our people safe."

--Pakistani duplicity. "Truths might be told in Quetta, but

never on purpose."

--On the American public's lack of interest in our wars.

"You go to a bar, guys buy you a round, ask about what you're doing. But if you

tell them, their eyes glaze over. It's too far away, confusing. Plus they're

ashamed about it because they're getting drunk in college, mommy and daddy

paying the bills, and you're putting your butts on the line for them every day.

They don't want to think about it."

--On today's American generals: "No one ever got stars on

his collar by taking chances."

I'd also be interested in knowing if Joby Warrick thinks of the book. I will ask him.

April 9, 2012

What Tom would like to read in a history of the American war in Afghanistan

I think I've mentioned that I can't find a good operational

history of the Afghan war so far that covers it from 2001 to the present. (I

actually recently sat on the floor of a military library and basically went

through everything in its stacks about Afghanistan that I hadn't yet read.)

Here are some of the

questions I would like to see answered:

--What was American force posture each year of the war? How

and why did it change?

--Likewise, how did strategy change? What was the goal after

al Qaeda was more or less pushed in Pakistan in 2001-02?

--Were some of the top American commanders more effective

than others? Why?

--We did we have 10 of those top commanders in 10 years?

That doesn't make sense to me.

--What was the effect of the war in Iraq on the conduct of

the war in Afghanistan?

--What was the significance of the Pech Valley battles? Were

they key or just an interesting sidelight?

--More broadly, what is the history of the fight in the

east? How has it gone? What the most significant points in the campaign there?

--Likewise, why did we focus on the Helmand Valley so much?

Wouldn't it have been better to focus on Kandahar and then cutting off and

isolating Oruzgan and troublesome parts of the Helmand area?

--When did we stop having troops on the ground in Pakistan?

(I know we had them back in late 2001.) Speaking of that, why didn't we use

them as a blocking force when hundreds of al Qaeda fighters, including Osama

bin Laden, were escaping into Pakistan in December 2001?

--Speaking of Pakistan, did it really turn against the

American presence in Afghanistan in 2005? Why then? Did its rulers conclude

that we were fatally distracted by Iraq, or was it some other reason? How did

the Pakistani switch affect the war? Violence began to spike in late 2005, if I

recall correctly -- how direct was the connection?

--How does the war in the north fit into this?

--Why has Herat, the biggest city in the west, been so

quiet? I am surprised because one would think that tensions between the U.S.

and Iran would be reflected at least somewhat in the state of security in

western Afghanistan? Is it not because Ismail Khan is such a stud, and has

managed to maintain good relations with both the Revolutionary Guard and the

CIA? That's quite a feat.

Anybody got a recommendation on what to read that covers all

this? Maybe articles that explain some of it?

Quote of the day: Colin Powell on the roles of the national security advisor

A few months ago I was re-reading Colin Powell's memoir, My

American Journey, and liked his summary of the job of being national

security advisor: "judge, traffic cop, truant officer, arbitrator, fireman,

chaplain, psychiatrist, and occasional hit man." (P. 352)

I re-read Powell's book and H. Norman Schwarzkopf's memoir, It

Doesn't Take a Hero, back to

back. I was surprised to find I enjoyed both more now than I did the first

time, when they were first published long ago. I suspect this was because back

then I read them as a reporter digging for news, while this time I was looking

more broadly to understand both men and their sense of the Army in which they

served.

Then I read Karen DeYoung's bio

of Powell. "The Bush administration had clearly manipulated Powell's

prestige and reputation, even as it repeatedly undermined him and disregarded his

advice," she writes, and then asks, Why had he let them do it? Part of the

answer, she concludes, was that "he had been winning bureaucratic battles for

so many years that he simply refused to acknowledge the extent of the losses he

had suffered." He also had a sense of duty, she noted. And, she concluded, "He

was a proud man, and he would never have let them see him sweat." (Pp. 510-511,

DeYoung, Soldier.)

April 6, 2012

Tales from the C2 crypt: The American structure for Libya was pretty confusing

The new issue of Prism has a fascinating article

about American command arrangements for the Libya operation earlier this year.

The authors, three souls who toiled in the lower depths of

the Joint Staff's J-7, write that, "the decision was made to retain AFRICOM as

the supported command, with USEUCOM, USCENTCOM, USTRANSCOM and U.S. Strategic

Command (USSTRATCOM) in support."

Sounds simple, but wait: AFRICOM doesn't have any forces, so

EUCOM became "de facto force provider." It is almost as if EUCOM were acting

like a service. (Which would make it our sixth service, after the Army, Navy,

Marines, Air Force, and SOCOM, which already effectively has its own civilian-led

secretariat, in the SO/LIC bureaucracy.)

It gets even more complicated. Many aircraft were flying from bases in

EUCOM's area of responsibility, so EUCOM "retained OPCON of these forces."

What's more, EUCOM had other fish to fry, so reported Adm. Locklear, "We were

responding to OPCON pleas of the provider to make his life easier rather than

the OPCON needs of the commander." It's like a waterfall running in

reverse.

Also, it turned out that AFRICOM lacked the ability to

actually run an operation. (Interesting side fact: Half its staff is civilian,

and it had never rehearsed to run anything.)

Final bonus fact: The U.S. military has apparently come up

with the worst acronym I have heard in a long time: "VOCO." The article's

authors quote an Army brigadier as stating that in the Libyan operation, there

was "Lots of VOCO between all levels of command." It stands for "verbal orders

of the commander." But hold on: Aren't all

orders are verbal, unless the guy is pointing or something? What the

poor general meant was "oral orders of the commander." That would be "OOCO."

I'd prefer "Unwritten orders of the commander," which would be "UOCO," but that

is too hard to pronounce. It could make you poco loco in the coco.

And remember at this point we haven't even gotten into the

command arrangements with the other 14 nations in the anti-Qaddafi coalition

(AQC).

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: Jeremy and Imi reunited at last

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

This week U.S. Marine Lance Corporal Jeremy Vanhoose welcomed

home, officially, his former partner, MWD Imi -- or as she's otherwise described

by Jeremy's mother, "the missing piece to

Jeremy's puzzle of recovery."

While on patrol in Sangin Afghanistan last August, Vanhoose

and his unit encountered not one but three IEDs. Imi alerted to the danger, but

setting off the devices couldn't be helped. In the explosion Vanhoose lost his

left foot and sustained "shrapnel wounds to the right leg, back, and head" and

was medevaced from the scene. As soon as he was able, Vanhoose was quick to let

others know that he didn't blame Imi for what happened saying,

"she was onto something and I just took one more step."

Reported stories about this team are so far scarce, but the

pair is said

to have been a close

one. Vanhoose was a steadfast handler who spent long hours training with

Imi, a German shepherd, before their deployment to ensure they were as ready as

possible. In almost three months of service the team is said to have had

approximately two-dozen finds. It is a dedication and commitment that Vanhoose

has applied to his recovery.

From what I gather from the personal and emotional account

that Ms. Vanhoose gave in January to Silent Rank Sisterhood (a nonprofit

organization devoted to offering resources and support to military families), after

sustaining his injury Jeremy was told that he would be able to adopt Imi. It

turned out to be a promise of support that was more complicated to secure than

the family had anticipated. The question of whether or not Imi might have to redeploy

surfaced after Jeremy returned to the States in September and the adoption became

uncertain. [[BREAK]]

But Vanhoose's mother, Leisa, a self-described "proud Marine

mom" led the charge, what appears to have been a tireless campaign of letter

writing and rallying Internet

support, to get Imi home to Jeremy. Efforts no doubt, which did not go

unnoticed. Today, Mama Vanhoose thanked Jeremy and Imi's Facebook supporters -- she

estimates the page has reached some 247,574 users -- for their well

wishes, concern, and now the shared celebration.

It is indeed a happy reunion for the family with perhaps

even deeper meaning. When Jeremy joined the Marines after graduating from high

school, he was following in the footsteps of his older brother, Joseph, who had

also enlisted in the Marine Corps but was diagnosed with cancer just before he

received deployment orders to Iraq. He succumbed to his illness and passed away

in 2007.

Adopting Imi may have been a long and fraught-filled journey for the Vanhooses,

but now there are two Marines in their household once again.

Side note: As it stands now the MWD adoption process,

especially for those canines still considered viable for active duty, can be

painstakingly slow and arduous. However, I've heard accounts from both sides of

the table; devoted handlers and their families who are keen to bring their

former partners home and from program

managers who deal with the requests and are bound not only by regulations but the

high demand and continuing need for these dogs downrange. I have yet to

encounter anyone involved in this process who isn't trying to do what's best

for the handlers, dogs, and for the

troops on the ground. There is legislation in the works that addresses the

retirement and adoption process of MWDs, something we'll address in an upcoming

post.

Hat Tip: MWD Facebook page.

Quote of the day: Time for the Army to reclaim its professional jurisdiction

1st

Lt. Anthony Formica writes

in the new issue of Military Review

that, "the Army has essentially relayed the messages that it prizes warriors

over soldiers." I think this is correct, and quite damaging to the service.

Formica

continues, "and that if it could rid itself of the burdens associated with

professional soldiering to better pursue the samurai ideal, it would do so,

thereby abandoning professionally critical jurisdictional ground."

The article kind

of rambles around a bit, and then lands on this subject again: "Once

significant combat actions have ceased the Army must begin to regenerate

masters of the profession's abstract knowledge base to reclaim its lost

intellectual jurisdiction."

I suspect he is

probably right. Contractors should not be writing doctrine or teaching officers

how to be officers. Doing those tasks is one of the ways that your next

generation of leaders is created. (Also, as has been pointed out before, having

officers returned from our wars write doctrine means that knowledge from those

wars is injected into current doctrine.)

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers