Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 149

November 6, 2012

Why doesn't the Army want to be a real Army, and think about its actual tasks?

By Matthew Schmidt

Best Defense department of Armyology

The U.S. Army doesn't seem

to want to be an army. Or, rather, they seem to want to be half an army, like

(no offense) the Marines! They want to do the first part of war, the invasion

part, but not the less glamorous, more difficult, messy part that is occupation. The Army's seeming disdain for doing the work of occupying a

place after the Hollywood scenes of major combat are over betrays a culture

that just doesn't get the nature of (modern) war.

To be clear, plenty of

individual people in the Army do understand the importance of thinking about

the post-combat phase of warfare, but the institutional culture, the code of

language, and behavior that dominates the everyday world of the Army is

decidedly focused on the minutiae of combat tactics.

Put another way, the Army

has lost a clear sense of what makes it different from the other services. The

Navy and Air Force can fight. The Marines can fight. But only the Army can

occupy. This is the essential difference in the services when you strip away

all the trivia. Armies are built to occupy places. They are meant to be the big

ground force that sweeps over an area and sits on it. The Navy can project

power to 'turn' a stubborn mule of a regime back in the right direction. The

Air Force can heavily influence the ground game by providing air-space

superiority for troops, and it can project power like the Navy. And the Marines

can kick in the door to places and conduct small-scale land operations for

limited periods of time.

But only the Army is big

enough to extend control over the ground across an entire chunk of the planet

for any length of time.

Of course this usually

(but not always) means fighting conventional battles against other forces

similarly armed. So I'm not saying that major combat isn't part of the Army's

mission. But no other service can do what the Army should be designed to do

after the first part of the fight is done. No other service can control the

crucial space where real human beings live, engage in trade, or practice

politics. We like to imagine the art of war as being about winning the fight.

But at the highest level, as Tom pointed out in his

most recent Atlantic article, generalship "must link military action to political results."

This is, of course, just a restating of Carl von Clausewitz's famous dictum

that war should be understood as the continuation of political policy. Yet most

of Army culture is relentlessly tactical in nature, even in the staff college

where I teach.

I've always been curious

about this reading of military history. If you think of the history of the Army

as the story of the battles it fought from the Revolutionary War to today, of

course this is what you see. But a deeper reading of history shows that the

Army fought battles in order to occupy and administer large swaths of territory

with large populations for far more of its history. The battles of the Civil

War gave way to the occupation of the reconstruction era, a period of time that

had troops engaged in occupation operations three times as long as they had

combat. If you count the history of westward expansion, most of the work the

Army did involved a kind of armed public-administration, not Indian conquest.

The same is true of the Spanish American war, which saw U.S. troops conducting

counterinsurgency and civil affairs for years after in the Philippines. Add in

the post-WWII occupations of Germany and Japan, the long, tedious mix of combat

and occupation in Vietnam, and the extended occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan

and it's overwhelmingly clear that the Army's main historical work has been

occupation, not battle.

But we teach "operational

art" and "strategy" as though fighting battles is the only work of an army. It

isn't. It never has been. At best it's only half of what an army is asked to do

and it often isn't the most important part. We wonder how the Army fits into

strategic frameworks like the new AirSeaBattle, all the while ignoring the

obvious. We skimp on exploring the problems of using military force to achieve

the political ends that are the purpose of occupations, and effectively define

the work of generals and their staffs too narrowly, as a stringing together of

a series of battles in order to gain a military-strategic aim. We pay

relatively little attention to thinking about the work of generals as stringing

together actions best thought of not as battles, but as the problems associated

with using the resources that accompany military occupations to build political

regimes that further our interests.

What we should be doing

is devoting a much greater share of our time examining how the best generals in

history conducted occupations after the main fighting was done. This isn't just

the generalship of the future, it's the generalship of the vast bulk of

"military" history. Fighting is about the tactics of the battlefield. Winning

is about securing the victories of those battlefields. Neither the Navy, the

Air Force, or the Marines can secure battlefield victories where they

ultimately matter -- where people live. That's the Army's mission. We should

recognize that mission as being at least as important as winning in combat. And

we should educate, promote, and fire our military leaders to reflect that

reality.

Matthew Schmidt is

an assistant professor of Political Science and Planning at the U.S. Army

School of Advanced Military Studies. He originated the "

Matters Military

" blog at the Georgetown Journal of International

Affairs and has a book on developing strategic thinkers forthcoming from

Wiley/Jossey-Bass in 2013.

He can be reached at

mattschmidt@mattschmidtphd.net

. The views

expressed are entirely those of the author and are not endorsed by the U.S. Army

or the Department of Defense.

November 5, 2012

The job-cutting at Fort Leavenworth: A general from out there responds

By Brig. Gen. Gordon

Davis Jr.

Best Defense guest

respondent

Thanks

for posting the letter from one of our

faculty members

to your blog. When people's livelihood

is concerned, it is a matter of great importance -- and it demands care,

transparency, and thoughtfulness.

I'd

like to contribute to the discussion by explaining the 'why' of faculty changes

ongoing at the Army's Command and General Staff School, as well as the'how'

(partially addressed) and 'what' we are aiming to achieve.

First,

we have great faculty, military and civilian, at the Army Command and General

Staff College (of which CGSS is the largest school) who are committed to their

mission of developing the Army's future leaders.

Our

mission is the 'why' we have decided to change the ratio of civilian to

military faculty. To develop our the

Army's mid-grade leaders we need the right balance of graduate-level teaching

skills, scholarship, continuity (provided by our civilian faculty) and serving

role models, recent operational experience, and future military leaders

(provided by our military faculty).

Before

9/11 that balance was roughly 10 percent civilian, 90 percent military. Due to the exigency of supporting the wars

over the past decade that balance shifted to 70 percent civilian, 30 percent military. With reduction of commitments abroad and an

opportunity to rebalance, the Army leadership has decided that the optimal

ratio is 60 percent civilian, 40 percent military. We

are, after all, an institution which provides Professional Military Education

to Army leaders. To maintain the

military expertise required in our ranks, to provide development opportunities

(e.g. teaching experience), and to ensure the stewardship demanded of our

profession, we need the right balance of military leaders teaching other

military leaders -- a time-proven ingredient for a successful learning

military. The decision to move to this ratio

has been a matter of discussion for a couple of years and now we have the

opportunity to move to it.

There

had been serious discussion of reducing our faculty-to-student ratio due to

defense budget reductions, which would have meant losing significant numbers of

both civilian and military faculty. Fortunately, other offsets were made and we are able to maintain the

investment in quality Professional Military Education, which our leaders need

to be able to adapt and prevail against current and future threats.

As to

the 'how' of our reduction, there are several key points I want to share. Faculty have been informed from the outset as

options for change were being considered. We developed a plan in coordination with the Civilian Personnel Advisory

Center at Fort Leavenworth to release civilian faculty members employed over a

two-year period, so that the we could retain the highest performing employees

and so that no employee would be released before the end of his/her term of

employment. This allows faculty time to

transition out of teaching positions as we gain military instructors. Each teaching department identified

assessment criteria based on their respective content. For example, criteria for assessing faculty

members were different for the Department of Military History than for the

Department of Tactics or Department of Command & Leadership, etc. Each civilian faculty member was assessed --

high performer, average performer, below average performer -- and informed where

they stood.

To

reach a 60 percent civilian, 40 percent military faculty ratio required us to release up to

33 civilian faculty employed under provisions of Title 10, U.S. Code. However, that number has reduced as new

teaching positions have arisen to address increased Distance Learning enrollment.

There

are points made in the earlier blog which are not accurately represented. Some of the people referred to as leaving

have left for personal reasons unrelated to our faculty changes as the author

suggested. Some have left for higher

paying jobs. However, we have lost a few

good teachers and the changes in faculty retention may have played some part in

their decisions. That part of any

personnel change process is hard to avoid. What we can control is making sure that we retain or release the right

faculty members and that those we release are treated fairly and respectfully.

Some

readers may not be aware that employees hired under the provisions of Title 10

U.S.C. are not permanent employees. Our

faculty do not receive tenure as in civilian colleges and universities. All new

CGSC Title 10 employees receive initial terms of two years, and may apply for

subsequent terms of one to five years. As a management process to deal with the new requirements, we have

instituted a two year term letter for those seeking to be rehired. This policy was not meant to be permanent,

but to allow us to reach the new faculty ratio.

Finally,

we have an Advisory Council elected by the CGSC Staff and Faculty (primarily

civilian) that I rely on for feedback on issues of concern or friction. I meet with the leadership regularly and the

Dean, Directors, key Staff and I discuss each issue raised. The two year renewal policy has not been an

item presented by the council for us to review. However, given the current situation I am

going to ask the staff and faculty to provide feedback on the policy.

In

conclusion, we are re-structuring our CGSS faculty to increase the numbers of

active duty Army officers of the right caliber with fresh operational

experience to meet our mission in preparing student officers as well as provide

teaching experience to future military leaders.

Thank

you for providing a medium for discussion, and I hope this information is

useful. We are looking forward to your

visit out to us at the end of this month.

Brig. Gen. (promotable) Gordon

"Skip" Davis Jr. is Deputy Commanding General CAC Leader Development &

Education Deputy Commandant CGSC. He c

ommanded 2nd Battalion, 29th Infantry Regiment, and then was the

Deputy Brigade Commander, 3rd Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division. He also commanded the 2nd Brigade, 78th

Division (Training Support) at Fort Drum, New York, which he deployed in

support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. He also has served in Afghanistan, Bosnia,

Mozambique, Zaire, Rwanda, Congo, and Liberia.

As my big debut event in DC looms, a pattern emerges in reviews of the book

There's

a mega-event for my book Thursday night in DC. It is free, but to attend you

should to register here. There

will be a surprise guest.

Meanwhile,

more reviews of the book are pouring in. On the one side stand the unhappy

generals. Retired Army Maj. Gen. Robert Scales doesn't like it -- he calls it

unfair. He tells me he thinks in his review in Foreign Affairs that he is defending the

Army. Me, I think that he is defending today's Army generals. Retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Perry Smith also

posted a querulous review on Amazon.

Meanwhile,

the best of our military historians are greeting the book positively. Here is a good

review in Military

History magazine by one of the grand old men of the field, Dennis

Showalter. That comes on top of similar praise from three other big names in

the field -- Carlo D'Este, Hew Strachan and Brian

Linn.

See

a pattern here -- generals vs. historians?

Navy fires skipper, XO and engineering and ops officers of USS Vandegrift

The

four officers of the frigate were sacked for drinking

too much on a port visit to Vladivostok. Well,

what else is there to do there?

And

have you ever noticed how the Navy seems to do its firings on Fridays? I guess

that is traditional.

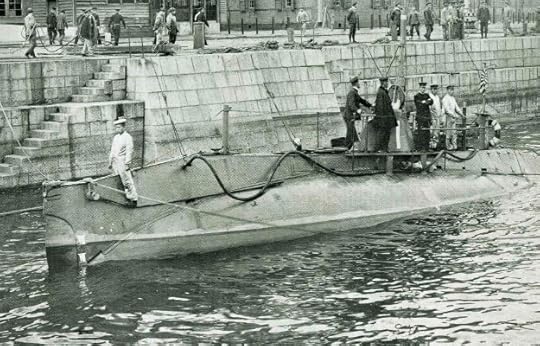

Naval stuff I didn't know: The Japanese navy patrolled Med during WWI, and the Nazis planned a fleet of aircraft carriers

Paul

Kennedy reports that

in World War I, when the Japanese were allied with the UK, they patrolled the

Indian Ocean at the request of Britain. They also "dispatched a dozen

destroyers for anti-submarine work in the Mediterranean," he notes.

Nor

did I know that in the German defense plan of 1938 called for it to build four

aircraft carriers.

Finally,

I learned that during World War II, more German U boats were sunk by Allied

aircraft (288) than by surface ships (246). (Another bunch were deep-sixed by

combined actions.)

November 2, 2012

Fred Kaplan's challenge: Pick a book from each war covered in your new book

Fred

Kaplan, who writes for Slate, asked me the other day to

name a favorite book from each war I write about in my new

book, which came out this week. So I wrote it up, and sent it

to Fresh Air, Terry Gross's great

interview show on NPR. You can listen to her interview of me, which ran

yesterday, here.

(Meanwhile, here is a review

of my book by one of the best younger military historians in the

country, Brian Linn. And here is a piece in Huffington Post by the intrepid Andrea

Stone.)

But

you can read my booklist just by keeping on reading:

World War II

This is almost impossible. Where to start? There are so

many good histories, so many powerful memoirs, starting with Winston

Churchill's and Field Marshal Slim's. Also, Rick Atkinson's trilogy on the

Army's War in Europe-the last volume will come out next year-is a must read.

But when I think of my single favorite, I think it has to be Eugene Sledge's With

the Old Breed in Peleliu and Okinawa.

Korea

I'm tempted to pick Martin Russ' The Last Parallel,

a memoir of being a Marine near the end of the war. But the centerpiece of the

war really for me is the Chosin Reservoir campaign. For that, I think I'd have

to pick Roy Appleman's East of Chosin, a painful history of the

forgotten fight of an Army regiment that was wiped out on the east side of the

reservoir.

The Vietnam War

An odd war-thousands of volumes written, but no one great

book. Right now I am in the middle of Karl Marlantes' novel Matterhorn,

which is terrific. But I won't know if it is my favorite until I finish it.

Until then, I think I will have to chose James MacDonough's Platoon Leader.

A close second

is H.R. McMaster's Dereliction of Duty, a tough read but an important

one.

The 1991 Gulf War

For this one, I think I'd have to go with The

Generals' War, by Michael Gordon and Bernard Trainor. It covered the war

but also provided some prescient doubts about the quality of U.S. military

leadership.

The war in Iraq

Putting aside my own works on this war (Fiasco and

The Gamble), I think my favorite so far is The Long Walk, a

memoir by a bomb disposal technical, Brian Castner.

The war in Afghanistan

The overall book hasn't been written yet. But I think the

ones that capture the feel of how this war was conducted are the memoirs about

how Osama bin Laden escaped at Tora Bora. The place to begin is probably Gary

Bernsten's Jawbreaker.

What defense blogs should I be reading? Send along your suggestions, please

Every

morning I read about 40 blogs on national security and international news.

Lately I've noticed some good sites (such as Phil Cave's military law page) have

become less active in posting, and so I demoted his and several others to a

"check once-a-week" category.

That

means I have openings for other blogs to be on my daily read roster. What would

you suggest that is related to the world of national security? Especially have

some new ones surfaced that I might not yet have noticed? Let me know.

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: Friday photo: Ty's got your back

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

IDD detection dog Ty keeps watch while his handler Marine LCpl. Brandon Mann, a Texas native with the 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion sweeps the area with a look through his automatic rifle. The pair along with other Marines and sailors was in Helmand Province assigned to a "clearing and disrupting operations in and around the villages of Sre Kala and Paygel during Operation Highland Thunder" on February 2.

November 1, 2012

National cost-imposing strategies: Maybe there really is nothing new under the sun?

Back

in the late Cold War, there was a lot of talking of an American strategy that

imposed costs on the Russkies -- costs they couldn't afford, for things like

national missile defense. It seemed pretty snazzy at the time.

It

turns out that this is nothing new. Paul Kennedy, in his terrific study of The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery,

quotes the Duke of Newcastle as stating in 1742 that, "France will outdo us at

sea when they have nothing to fear on land. I have always maintained that our marine

should protect our alliances on the Continent, and so, by diverting the expense

of France, enable us to maintain our superiority at sea."

Kennedy

says this was the key to British policy for centuries: Keep Europe in a balance

of power so that no one nation dominated the continent, and all nations there

would have to focus on land power at the expense of sea power. Hence Britain's

"perfidious" reputation -- it didn't care much about the nature of its alliances

as long as it could balance European powers while it expanded its empire

outside Europe. He writes that, "of the seven Anglo-French wars which took

place between 1689 and 1815, the only one which Britain lost was that in which

no fighting took place in Europe." This pattern gave rise to the expression

that France lost Canada in Germany.

This

approach worked until 1914.

The

British occupation of Gibraltar grew out of this strategy. By having a base at

the mouth of the Mediterranean, the British could deter the French from moving

their Mediterranean fleet out to join their Atlantic fleet.

Kennedy's

book reminds me a lot of Piers Mackesy's The War for America in

that it teaches not just history but strategy. I am surprised that no one told

me to read it years ago.

How Tom got to be that way

The

sub-headline on this Washingtonian

magazine profile of me

overstates my influence, but I think the article is straightforward and fair.

Here

also is a fun

exchange I had with the talented Spencer Ackerman at Wired.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers