Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 137

December 31, 2012

A CIA reading list

As

you compile your resolutions for the new year, Best Defense is offering three

different reading lists to help you. Here is a list from CIA veteran

Hayden Peake.

One reason I don't write much about intelligence is that I don't know much

about it -- as this list reminds me -- I haven't read any of them. But he does.

Current Topics

Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance: Acquisitions, Policies and

Defense Oversight, by Johanna A. Montgomery (ed.).

General

The Dictionary of Espionage: Spyspeak into English, by Joseph C.

Goulden.

Historical

Black Ops Vietnam: The Operational History of MACVSOG, by Robert

M. Gillespie.

Classical Spies: American Archaeologists with the OSS in World War II

Greece, by Susan Heuck Allen.

Dealing With the Devil: Anglo-Soviet Intelligence Cooperation During the

Second World War, by Dónal O'Sullivan.

Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies, by Ben Macintyre

Enemies: A History of the FBI, by Tim Weiner.

Franco's Friends: How British Intelligence Helped Bring Franco To Power

In Spain, by Peter Day.

Gentleman Spymaster: How Lt. Col. Tommy 'Tar' Robertson Double-crossed

the Nazis, by Geoffrey Elliott.

The Ideal Man: The Tragedy of Jim Thompson and the American Way of War, by Joshua Kurlantzick.

Joe Rochefort's War: The Odyssey

of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway, by Elliot Carlson, with a foreword by RAdm. Donald "Mac" Showers, USN

(Ret.).

Memoir

Malayan Spymaster: Memoirs of a Rubber Planter Bandit Fighter and Spy,

by Boris Hembry.

Intelligence Abroad

Historical Dictionary of Chinese Intelligence, by I.C. Smith and

Nigel West.

Israel's Silent Defender: An Inside Look at Sixty Years of Israeli

Intelligence, by Amos Gilboa and Ephraim Lapid (eds.).

Learning from the Secret Past: Cases in British Intelligence History, by Robert Dover and Michael S. Goodman (eds.).

Main Intelligence Outfits of Pakistan, by P.C. Joshi.

The Politics of Counterterrorism in India: Strategic Intelligence and

National Security in South Asia, by Prem Mahadevan.

Stalin's Man in Canada: Fred Rose and Soviet Espionage, by David Levy.

Stasi Decorations and Memorabilia: Volume II, by Ralph Pickard, with a foreword by Ambassador Hugh Montgomery.

December 28, 2012

Soldier poets of the Great War (III): The gates of Heaven lacking guards and wire

From T.P. Cameron

Wilson, who was killed in 1918:

. . . The gates of Heaven were open, quite

Unguarded, and unwired.

In case those two negative reviews of my new book on generalship got you worried

In contrast to Col. Gentile's

review that I mentioned last week, and the

negative review by the British hussar that I

carried the other day, here's the word on my new book from the

just-released issue of the Army's Military

Review:

THE GENERALS IS

a controversial but nonetheless

important read for military professionals seeking

to understand the management of Army generals over the last 70 years.

.

. . Readers may be tempted to dismiss Tom Ricks' book as one written by a

prejudiced outsider, a journalist who has never served as a soldier. This would

be a mistake. The

Generals contains

considerable research,

much from first-hand sources of soldiers, officers, and general officers. Those

sources frame Ricks'

discussion. Ricks also draws material from letters, journals, and duty logs.

The reader gets the

feeling of looking over the shoulder of people engaged in one of the most

dangerous and vital endeavors

in which military professionals engage: fighting and winning the wars.

.

. . Both civilian and military DOD personnel should read the book. Some readers

may find Ricks'

premises questionable and his conclusions unsatisfying. However, rather than

avoiding a controversial

discussion, the Army and the rest of the Department of Defense should face this discourse

head-on and use it to improve itself. Even if some think he fails to diagnose

the disease, the

symptoms he describes are undeniable, as evinced yet again in the recent series

of senior officer

meltdowns. The Generals is an excellent source for leader

development programs.

Don’t 4get the DC beer call 2nite

Bring

your thoughts,

and look for the table with the smart jarheads. 6 pm tonite at

Bier Baron (AKA the Brickskeller)

1523 22nd Street Northwest

Washington, DC 20037

And

while you are there, please raise a glass to the memory of H.

Norman Schwarzkopf. I have been critical of him, but

there is no doubt he did his best.

December 27, 2012

Face it, Goldwater-Nichols hasn’t worked

By Col. Gary Anderson (USMC, Ret.)

Best Defense department of defense de-organization

Three decades ago, when the military reform movement was

beating the drum for what became the Goldwater-Nichols legislation, a number of

us in uniform and out, were trying to sound a cautionary note. We got outvoted

and the legislation passed. "Jointness" became the new mantra, and arguing

against it became heresy, if not hate speak. Based on recent events, it may be

time to reassess Goldwater-Nichols.

The proponents of the elevation of jointness to absolute

military supremacy claimed that it would prevent long open ended wars such as

Korea and Vietnam by giving the President and Secretary of Defense better

military advice than they got in such conflicts. The reformers also promised

more competent and professional military leadership and less cumbersome command

arrangements. The results of the wars in Kosovo and Operation Desert Storm

in the immediate aftermath of the Goldwater-Nichols legislation seemed to

confirm the validity of those promises; but somewhere in the ensuing decades,

the wheels came off.

Instead of fast and clean conflicts, we got Afghanistan

and Iraq. Not only were they long and strategically muddled, they were also

poorly executed by the joint institutions that Goldwater-Nichols was supposed

to fix. In his new book, The Generals,

Pulitzer Prize winning author Tom Ricks ruthlessly exposes the myth that our

generalship was improved by Goldwater-Nichols. He argues that the generalship

of the likes of Tommy Franks and Ricardo Sanchez was marked by absolutely

mediocre planning and strategic leadership. In Afghanistan, we have had

averaged one supreme leadership change a year. In addition the Navy relieved

more commanders than in any time in its history, and the other services have

been plagued by instances of misconduct by senior officers.

Many of those who argued for Goldwater-Nichols used the

German General Staff as a model to aspire to. While the German generals were

superb at tactics, they were lousy strategists. After winning the wars of

German unification in the nineteenth century, they lost two disastrous world

wars. As Ricks points out, our generals are good tacticians, but poor

strategists. Ironically, the reformers got what they wished for.

The problem is not just with general officers; our joint

staffs have become bloated with unneeded officers due to the legislative

mandate that every officer aspiring to reach flag rank has to serve two years

in a joint billet. No-one has ever explained how serving as a Joint Graves

Registration Officer will produce our future Grants, Shermans, or Pattons.

There was a time when being selected for major was the great cut in an

officer's career. Today the running military joke is that if you can answer a

phone, you can become a Major.

Strengthening the unity of command of joint operations

was a good idea, but most of our regional joint staffs are bloated to a point

where they ill-serve the commanders who lead them. Because of the number of

joint officers the law requires. Admiral Halsey and Rommel won their most

famous victories with staffs a fraction of the size of the average U.S. Army

brigade combat team staff today.

This can be fixed. Unfortunately, we will need even more

legislation. First, we need to get rid of the requirement that all general

officer candidates be joint certified. All of our generals and admirals don't

need to be superb joint war fighting experts. Rommel was not a General Staff

officer, and Halsey would not have wanted to be one. The joint staff track

should be reserved for those who aspire to eventual joint command and staff

positions, but there should not be a stigma for those who want to lead air

wings, Marine Corps Expeditionary Forces or Navy fleets; we need real warriors

as well as soldier-diplomat strategists.

A smaller, more elite joint staff corps would allow us to

concentrate on creating real strategic expertise. Joint Staff candidates should

be put through a series of rigorous force-on-force seminar war games that would

test their capability to make both diplomatic as well as military decisions

against competent, thinking opponents. Those candidates who come up short in

such tests should be sent back to their services with no stigma to their

careers. Successful graduates would still spend time with troops, fly

airplanes, or drive ships when not serving on joint staffs; however, once

selected for flag rank, their command and staff positions would be primarily

joint. This would allow joint staffs to be smaller and more efficient.

Goldwater-Nichols has institutionalized mediocrity. We can, and must, do better.

Gary

Anderson, a retired Marine Corps officer, is an Adjunct Professor at the George

Washington University's Elliot School of International Affairs.

A response to Lady Emma: No, start by actually helping the Iraqis do things

By Steve Donnelly

Best Defense guest respondent

Emma Sky's recent

paper for CNAS provides a welcoming and Iraqi-freshened perspective to

the most recent of many chapters in the story of U.S. relations with Iraq.

But there remain a great many unspoken undercurrents in

the human interest stories of a U.S. CPA and military actor, no disrespect

intended, rather than a professional analysis of the gaps and deficiencies

identified -- which all relate to Iraqi self-governance and support for Iraqi

civilian institutions.

Emma's stories reminded me of several meetings in Tikrit

and Baghdad in 2008, which, I believe, underscore the complexities of the US

muddle, and the limitations on U.S. successes in light of our past history.

On a crisp morning in January 2008, a military convoy

wound its way through Tikrit's morning traffic to deliver three State

Department civilian advisers to Salah ad Din's provincial headquarters. Parents

walked their children to the local schoolhouse, garbed in the clean, pressed,

yet shabby garb of war refugees, wary of the passing convoy. The turret-mounted

M60 intermittently pop-popped warning shots to oncoming traffic at each

intersection, as the electronic jammers shut down all civilian cell phone

traffic. Children with no parents to take interest sat by the roadside selling

gypsy gasoline from small containers. All these scenes were visible to the

civilian advisers through the grimy window of the Humvee.

As the provincial headquarters' halls were swept by the U.S.

military escort, widows and their young children, descending into PTSD events

when confronted with the same soldiers that, under Big Ray, had once kicked

down their door and taken Daddy away, and likely to be suicide bombers, were

cleared before the civilian advisers entered to attend a brief meeting with

Salah ad Din's civilian leaders.

The civilian advisers were warmly greeted by elected

officials from the Provincial Government, mostly Kurds favorable to the United

States, and "democratically" elected as a result of the majority-Sunni boycott

of elections in Salah ad Din and Ninewa. But the Iraqi civilian administrators

were, on first meeting, typically reluctant to speak directly to an American,

whether military or civilian.

The reasons for that reluctance were understandable,

given their backgrounds. Some were survivors of the Shia opposition left by the

United States to fend with Saddam after Desert Storm, highly-skilled civil

engineers returning from prestigious exile in Kuwait to find their country in

ruins as it had been after the Iraq/Iran War, but with the resources and

responsibilities for reconstruction now in the hands of well-intended but

unskilled U.S. military E-5s and 0-3s. Most important was an unwillingness to

be publicly identified as "collaborators," when, after the United States left,

reprisals would be certain, and did occur.

After the meeting, two civilian advisers were directed to

another room while the return convoy was being organized. After very careful

negotiations through one of the Sunni leaders, they had the opportunity to meet

in private with the former civilian engineers and administrators who had

operated and rebuilt Salah ad Din before the Baathist purges. They knew where

everything was, how to fix it, and were anxious to help, but could not do so

directly.

As the U.S. civilian advisers intermediated between the U.S.

military, and Iraqi provincial and national leaders to rebuilt the bridges over

the Tigris, a complex chain of communication was required, with "anonymous"

help from the former Baathist administrators, and indirect calls from current

administrators and anti-Americans unwilling to be identified as direct

collaborators, but needed to get their country reconstructed.

Through an equally byzantine chain of events and

contacts, two of the civilian advisers were invited to attend an Iraqi meeting

(no U.S. military, please) in Baghdad in June 2008, where ministry and

provincial officials were meeting to coordinate procedures for the upcoming

2009 budget deliberations.

Here, behind closed doors in the Al Rasheed Hotel's main

ballroom, Iraq's leading national and provincial technocrats were blunt in

their criticisms of the current state of affairs, the crooked politicians they

were confronted with, and the hope that by returning to their older and

technically-based processes for project and budget considerations, hoped to

move the system to one based on genuine need, public participation, technical

reviews and cost/benefit frameworks to get Iraq moving again.

As the meeting proceeded, the old-timers mentored the

handful of confused post-Saddam administrators on the old cost-budget analysis

processes and technical studies used in the older processes, and agreements

were made to republish and re-distribute the old budget manuals, so that a

modern and functional government could hopefully emerge.

Why were these two State Department civilian advisers

being invited into meetings to which U.S. military and prior CPA advisers were

never invited, and embraced by the civilian solutions that the CPA and U.S. military

had not engaged?

Each was an actual U.S. civilian developer, planner,

engineer and builder. They spoke the same language as the technocrats,

understood the complexities of the systems problems, and the routine paths for

solutions. Bureaucrat to Bureaucrat. Bridge Engineer to Bridge Engineer. Water

Treatment Plant Operator to Water Treatment Plant Operator. Builder to Builder.

The language, social, and cultural barriers were irrelevant to the common

language of troubleshooting and public systems.

Most important, they had each been sent with explicit

instructions from Foggy Bottom and Ambassador Crocker's "bubble" to find those

solutions, and were empowered by MND-North Commander MG Mark Hertling, and his

experienced command staff, who all came with the same common mission: Give Iraq

back to the Iraqis.

The lessons of these many experiences were distilled by

the State Department civilian advisors into a report arguing for the rapid

transition to Iraqi civilian government based on three insights: (1) Iraqis, by

their national culture still driving them, are inveterate builders who had

proudly built and rebuilt their country as each war and flood swept through;

(2) Iraq had invested heavily in training core groups of administrators, public

works managers and engineers, who were available, respected by their peers, and

anxious to take responsibility for restoring a functional public service

structure, but needed help to get past the interim political leaders (many of

which were our own); and (3) that joining these insights into SOFA negotiations

could provide rapid transition to Iraqi government, and enduring value for

future U.S. and Iraqi relationships.

Where Emma Sky's limitations, as a former CPA

Administrator and Odierno adviser are most apparent, is perhaps unintended bias

toward what the United States, rather than Iraqis, shoulda or coulda have done

during and after a chaotic and ill-informed occupation which drove out the very

Iraqi engagement and responsibility that was the only viable way forward, and

the lack of training and technical experience in the actual systems of

government needed to address the lingering issues.

If anything could be recommended at this point, it would

be for the Obama Administration to abandon the unwanted meddling in Iraqi

police affairs and ineffective training, and to openly and effectively engage

that broad Iraqi public through positive political focus on the "plain vanilla"

operations of civil government systems and technical advice, which the United

States has an abundance of and the Iraqi public seriously needs.

It is clear that the spooks and spies, by not leaving a

basically functional, and somewhat reconciled government, lost their entry,

and, perhaps, ceded that U.S. role to Iran (actually more to Turkey).

Focus on what the Iraqi public actually needs, and they

will tolerate, if they have to, a handful of spooks and spies, but it is

axiomatic that if the United States is viewed by that Iraqi public as a helper

rather than an unwanted intervener, less spooks and spies would be required,

and valid intelligence on the actual Iraq and its problems would be abundant

and routine.

The

Lesson from Benghazi and Syria: Effective U.S. engagement in

these countries is going to require a more sophisticated and meaningful

exchange with these many publics than the current military and diplomatic

systems consider. Big U.S. footprints, soldiers, and colonial occupiers are

unwelcome. Better to use internet engagements to link Iraqi administrators to U.S.

technical resources, then re-engage overtime.

Stephen

Donnelly, AICP, is a Crofton, MD-based planning and development consultant who

served as Senior Urban Planning Adviser, US Department of State, Iraq

Reconstruction, during the civilian surge (2007-2009).

Mission command is nice but I suspect we are indeed only paying it lip service

By Richard Buchanan

Best Defense office of mission

command

In 1993, when I left the Army

as a CWO (HUMINT/CI) myself and another CWO (Order of Battle) were training 7th

Infantry Light non-MI personnel on MI skill sets using a hand-jammed two-week

NEO scenario exercising against Abu Sayfeh. Down right counter guerrilla if you

ask me as we were using my Special Forces Vietnam experience to frame the scenario.

Bottom line up front -- if a light fighter is trained well in his infantry

skill sets counter-guerrilla operations are not a problem -- it was true in

1993 and it is just true in 2012 so why did we have to create COIN?

We were actually breaking

ground in 1993 by creating the CoIST and DATE concepts years before they became

standard terms. The MI Center in Ft. Huachuca was interested in the scenario

and concepts of our version of CoIST/DATE, but came to the decision that

guerrilla warfare was where the Force was not heading so they basically canned

what had been provided to them.

I then left the Force and

moved into the IT world of ATT and Cisco where for years we spoke using the IT

slogan "people, processes, tools" long before the Army broke into the G/S6

world.

Now 29 years later the Army

has "people, processes and tools" -- People is a PME system generating Cmdrs

and Staffs, Processes is Science of Control, and Tools is multiple mission

command systems.

I recently meet (after 29 years)

that same retired CWO who has as a retiree done his rotations to Iraq and

Afghanistan and just as I am he is still trying to educate the Force. When we

met we simply smiled and almost at the same time said "boy did we get it right

29 years ago" and then compared notes on what has been working and what is

failing since 1993. There are not many of us greybeards still out there working

with the Force -- and still the Force does not "listen."

So Tom's recent question ("Mission command is nice but what will commanders

actually practice it?") caused me to go

back and give it some serious thought as mission command is really something

some of us have been where possible practicing since 1993.

The question of how do we

facilitate mission command training in a Force that is centrically singularly

focused on mission command systems is a valid concern and yes one might in fact

think the Force is only paying lip service. Processes and tools are simple to

understand/control -- but the Art of Command is all about Leadership and right

now "Leadership" in the Force is a "black art."

The fuzzy "black art" thing we

call Art of Command with the equally warm and fuzzy terms of team building,

open dialogue in a fear free environment, and TRUST is the elephant in the room

that everyone wants to ignore. It is ignored in the AARs coming out of the DATE

exercises, it is ignored by MCTP AARs, it is ignored in Staff training

exercises and the list goes on.

WHY? The answer is easy -- not

many are comfortable and confident with themselves in the areas of Trust and

open dialogue or they have had negative experiences with these terms. Trust and

dialogue are hard to mentor day to day in the current Force.

Has anyone recently seen in

any CTC AAR or in any MCTP AAR a section on Trust? Meaning, was Trust being

demonstrated within the Staff or between the Cmdr and his Staff, a section on

how was dialogue being handled within the Staff or what the Cmdr's leadership

style was? That is, did it contribute to team building or did it push dialogue

and or contribute to trust being developed in his unit? Or was there ease in

the way the NCOs and Officers worked with each other. Or was failure tolerated

and learned from with the Cmdr leading the way in the lessons learned by a

failure?

Has anyone recently seen a CTC

AAR or a MCTP AAR speak out about the quality of the Cmdrs Mission Orders to

his subordinates (was it clear/concise) or did they speak about the quality of

the Commanders Intent -- two critical core elements in the "Art of Command"? Or

did the OCs speak about his and his Staff's micromanagement?

What is inherently missing is

a clear strong Army senior leadership emphasis on Leadership in the current

group of O5/6s and one/two Stars. Leadership that develops the team,

develops/fosters open dialogue and fosters Trust. If junior officers see that

emphasis in their daily routines then it becomes second nature to them -- right

now not many O5/6s are leading by example. We have way too few "truth seekers"

in the current O5/6 and one/two Star ranks.

In some aspects the necessity

for mission command (Art of Command and Science of Control-the processes not

the systems) has been articulated in ADP/ADRP 6.0, in the concept of "hybrid

threat" TC 7-100, in the doctrinal thinking behind Capstone 2012, and anchored

in the new DATE scenarios that are now standardized at the CTCs.

With the future of the Army

training being refocused on hybrid threats tied to DATE training exercises the

"Art of Command" is the key in moving forward. If the Cmdr has built his team

using the elements of Trust and open dialogue there is no "hybrid threat"

scenario that cannot be mastered by an agile and adaptive Cmdr/Staff.

In addition the concept of

"Design" then starts to make sense and just maybe we can move into a open

debate about whether the current decision making process MDMP makes sense in a

"hybrid threat environment" or should it be replaced by a different problem

solving process which actually "Design" and "mission command" demands.

Or as a recent article in

Tom's blog put it, "I am leaving the Corps because it doesn't much value

ideas." It is not only the Army that is having Trust issues. We are losing the

"best and the brightest" simply because senior leaders are not serious about a

"Leadership" that builds teams, fosters dialogue, and Trust.

Richard

Buchanan is mission command training facilitator with the JMTC/JMSC

Grafenwoehr, Germany training staffs in the areas of mission command,

MDMP/NATO Planning Processes, MDMP/Design, and Command Post Operations.

From 2006 to 2008, he rebuilt as HUMINT SME together with the Commander

Operations Group (COG) National Training Center (NTC) the CTC training

scenario to reflect Diyala Province. From 2008 to 2009, he introduced

as a Forensics SME into the NTC training scenario the first ever battlefield

forensics initially for multifunctional teams and then BCTs. From 2010 to 2012,

he trained staffs in the targeting process as tied to the ISR planning process

as they are integrated in the MDMP process. The opinions here are his own and

not those of U.S. Army Europe, the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, the

U.S. government, nor even the shattered remains of the once-proud New York

Jets.

December 26, 2012

Stress in special operators

A Navy SEAL commander committed

suicide in

Oruzgan, Afghanistan, last weekend. I hear through the grapevine

that there is a real stress problem among Special Operators that the leaders of

that community haven't dealt with well. There seems to be some belated recognition going on.

If you know a

survivor who might need a call during this season, lift up the phone. Here also

is a possible resource.

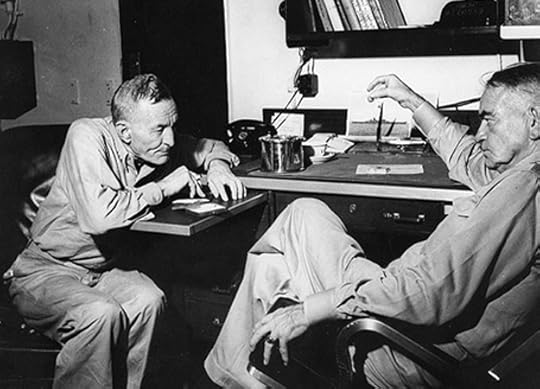

This is the negative review of my book that Col. Gentile should have written

By

Major Tom Mcilwaine, Queen's Royal Hussars

Best Defense guest

book reviewer

This

[The Generals] is an extraordinary book which will be widely

read by serving officers. It raises some very interesting ideas, is fluent and

persuasive and provides a junior officer with all the ammunition they would

require to ask some very awkward questions of their seniors. That said I am not

certain that it deserves some of the extravagant praise that has been heaped

upon it (notwithstanding the fact that some of that praise comes from those

such as General Zinni who know more about the art of generalship in the

American military than I ever could).

There

are a number of reasons for this. There is the problem of Ricks's use of

military history. He certainly has breadth, but depth is perhaps absent in

certain areas and he appears to ignore context, particularly when discussing

the actions of the British in World War Two but also when discussing Vietnam. He

tends to rely on secondary sources which support his argument (such as Lewis

Sorley's recent hatchet job of Westmoreland) and chooses to ignore largely that

which contradicts his argument. On the rare occasions when Ricks does

acknowledge other points of view (such as Millet's assessment of Ridgeway) he

fails to provide an analysis of their opposing view, trusting instead that the

power of his writing will explain why he is right and the opposing view is

wrong.

Secondly,

for a book based around the idea that Marshall is the acme of military

perfection and American generalship, and supposedly based on research so

extensive that he even read Marshall's officer litter, there is surprisingly

little on why Marshall is so good. He never deals with the fact that Marshall

was badly wrong on the decisive strategic question of when to invade Western

Europe, or that he was also wrong on the subject of the African campaign. The

overall picture we are given is that of a superb selector of men (despite the

fact that so many of his selections had to be replaced) and developer of a

human resources system without parallel, which is fine as far as it goes, but

perhaps not enough to justify the extravagant claims made by Ricks.

This

leads onto the third and biggest problem with the book. Ricks's argument is

riddled with passages and chapters that directly contradict that which has come

before. So Marshall creates a superb system - but the system fails without him

- so is it really a system at all? Marshall's system values character over

intellect - which is precisely the flaw Ricks identifies in the selection of

modern general officers. MacArthur leaves no mark on the US Army - but

Westmoreland (who whatever his flaws certainly did influence the US Army) is a

creature in the MacArthur mold. Korea is a disaster because commanders lack

command experience in war - which doesn't seem to hold either Eisenhower or

Petraeus back. There are many more and this habit extends to his oral defense

of his thesis and to his much publicized view that moral issues are of less

importance than professional issues. When asked for something that Marshall

doesn't do well at a Q&A session at CGSC recently his first answer was his

treatment of African-American soldiers - a moral issue - not his misjudgment of

the timing of Overlord - a professional issue.

At

that at root is the problem with this book. At a shallow level it has much to

recommend it. An interesting topic, covered in just enough depth to provide

useful talking points at a dinner party. But for a keen field grade officer it

lacks depth, rigor, coherence and understanding. There is a superb book to be written on the

flaws of American generalship and how to improve it (although I would suggest

that on the whole American generalship is rather good) and such a book would be

of great value but this most certainly is not it. Having read this book and

heard Ricks speak, I would argue that he is not, and never will be, the man to

write it. Worse, by writing a book as

riddled with inconsistencies as this and by then promoting with such a

breathtaking lack of humility he has done exceptional damage to the reformist

cause which he allegedly supports.

Major Tom Mcilwaine is a British Army

officer who is currently a student at the School of Advanced Military Studies

at Ft Leavenworth. He has deployed to Iraq as a Platoon Commander and Battalion

Operations and Intelligence Officer, to Bosnia as Aide to the Commander of

European Forces and to Afghanistan as a Plans Officer with I MEF(Fwd).

NRA magazine goes all pro-Obama!

Oddly enough the most

pro-Obama statement I have read lately was in the editor's letter in the

November issue of America's

First Freedom,

a magazine of the National Rifle Association. Among the "undisputable facts,"

we are told, are that "Obama supports reinstituting the failed ban on

semi-automatic rifles" and "Obama has already appointed two vehemently

anti-Second Amendment justices to the U.S. Supreme Court."

Sounds good to me! I

know that they don't mean it that way, but by the time I put down the NRA magazine I

was ready to contribute to the Joyce Foundation. I'd never heard of that outfit

until I saw them denounced in this issue of the NRA magazine. That interested

me enough to look them up.

Elsewhere in the same

issue, the NRA rejoices that the University of Colorado finally has a

"right-to-carry" policy "that allows permit holders to carry most anywhere on

the campus." Because you never know when you might have to bust a cap during

Economics 101?

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers