Susan Wise Bauer's Blog, page 4

February 28, 2013

When Did the Middle Ages End and the Renaissance Begin? Part Two of a Three-Part Reflection

Not long ago, I received the following email from a loyal reader:

You noted in your blog that the “History of the Renaissance World…will cover from the end of the First Crusade to the end of the Renaissance–which, in my view, is when Vasco da Gama rounds the Cape. That’s four hundred years, 1100-1500.”

Now, a gorgeous new art book entitled Gothic: Visual Art of the Middle Ages, 1140-1500 (Bruno Klein) is a recent example of what inspires my inquiry. Your Renaissance & Klein’s Middle Ages almost exactly coincide.

Furthermore, if you go to Wikipedia, you find, “The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned the period roughly from the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe.”

In grade school, I learned that the Middle Ages was the feudal period, which seems to be roughly the years you chose for your Renaissance volume. We never even addressed Constantine, Attila, or Charlemagne (clearly Medieval players).

Is there rhyme or reason to these apparent contradictions? Perhaps, the sociopolitical history and the (Gothic) art epoch are necessarily out of sync? Or, the difficulties you have expressed with encapsulating your historical volumes require a best-fit approach? Not being an expert in either world or art history, I turn to you to shed some light.

That was a very thoughtful, kind way to ask the question which has, on occasion, been asked with less finesse…for example:

Why did you pick the wrong years for the Middle Ages? Everyone knows that the Middle Ages go from 500 to 1500. I liked your first book but if you don’t know enough to get the Middle Ages right, I won’t read any more of them.

“Everyone knows” what the Middle Ages are, eh? Let’s take a closer look at that assumption.

Start with the word middle. In order to have a middle, you need to have something on either side. There’s no middle to a sandwich unless it’s got two slices of bread; without the top crust, the middle is the top and you’ve got toast, not sandwich. There’s no middle to a sonata or symphony unless there’s both a first and last movement, no middle of the night without both sunset and morning.

So what do the Middle Ages come between?

Traditionally, the classical age and the Renaissance. But now things get tricky. You can’t, after all, identify a “middle” until something exists on both sides of it. And so the “Middle” Ages didn’t exist until someone decided that a new age had begun after it. There is no Middle Ages without a Renaissance; the two eras came into existence simultaneously.

And who created this new reality?

Most of the responsibility lies with Petrarch, the Italian man of letters. Here’s an excerpt from my upcoming History of the Renaissance World, explaining how it happened…

Rome, pope-less and emperor-less, was in its usual chaotic and simmering state when the Italian poet Petrarch was crowned in Rome as Poet Laureate: the first time this honor had been carried out since ancient times.

Petrarch had been lobbying for the title, in a genteel and polished way, for some time. His father had been driven from Florence at about the same time as Dante; Petrarch, born afterwards, had been working in Avignon for years, writing a massive epic about the Roman general Scipio Africanus, travelling as the impulse struck him, and occasionally carrying out discreet diplomatic missions for the Avignon popes.

The Roman Senate, correctly interpreting Petrarch’s various oblique remarks as a request for the crown, invited the poet to Rome for his coronation. He chose Easter Sunday, April 18, 1341, as the day for the ceremony, and treated the assembled Romans and senators to an oration promising that the revival of the Poet Laureate position would help to bring about a new age in Rome. “I am moved also by the hope that, if God wills,” he told them, “I may renew in the now aged Republic a beauteous custom of its flourishing youth….Boldly, therefore, perhaps but–to the best of my belief–with no unworthy intention, since others are holding back, I am venturing to offer myself as guide for this toilsome and dangerous path; and I trust that there may be many followers.” The path was the path of learning; the rediscovery of the truths of the past, the history and literature of Rome’s glory days. Poets and scholars, Petrarch explained, would save Italy; poets and scholars would lead the Italian cities back into peace and prosperity.

The choice of Easter Sunday was not random. Petrarch had in mind a resurrection for his beloved Rome, a return to the days when the Roman Empire had been whole and powerful, not split between squabbling rulers and priests. Italy could recover her greatness by returning to the world of Rome before Christianity, Rome in the golden age of Cicero and Virgil, Rome between the coronation of Romulus and the rule of the emperor Titus. This, he later wrote, was “a more fortunate age,” and it was time to return to its ideals. Between that golden time and the present lay “the middle,” an era of “wretches and ignominy,” centuries of tenebrae: of darkness.

A classical age of light and learning, followed by a Dark Ages, culminating in a rebirth: a renaissance. Three epochs in history: antiquity, a Middle Age, and the present. Petrarch had laid out, for the first time, a scheme that would shape the next six hundred years of historical inquiry.

So there it is. Simultaneously, Petrarch created the Renaissance and the Middle, or Dark, Ages–and since his proposal struck a responsive chord with a number of his contemporaries, the labels gained in popularity.

But with all due respect to Petrarch (we’re all better off knowing that “Books have led some to learning and others to madness,” right?), his useful scheme has four limitations.

First, as Petrarch sees it, the Middle Ages has an entirely negative quality. It is defined by what it is not. It is not the classical age; it is not the rebirth; it is the bare space in between. It is a time without light, without fortune, without learning. It has no positive existence. Things without positive existence are darned hard to define. Or defend.

Second (a related point), the Middle Ages doesn’t end at a clear political, social, or cultural point. It ends when the Renaissance begins…and the Renaissance is a very, very slippery thing. Hold on to that point until the third and final post in this series.

Third, Petrarch’s Middle Ages only happens in Europe. It applies to absolutely no other place…and to make it work, we even have to redefine Europe as France/Spain/Germany/Italy/England/surrounding areas. The Middle Ages doesn’t work all that well for Poland, or for the Rus’ up there around the Baltic Sea, or even for the Hungarians. It doesn’t work at all for three-quarters of the African continent or for the Americas. It has very little to do with China, Japan, Korea, the southeastern Asian countries, or India. Which is (news flash) a very huge part of the world.

Fourth, as the email from my kind and loyal reader points out, “medieval” means very different things in different contexts. The “Middle Ages,” which Petrarch defined only as an absence, has come to stand for not only a period of time but a set of qualities. Medieval art is characterized by one set of qualities, medieval music by another, medieval Christianity by a third…and so on. Remember the quote from Ernst Cassirer that I used in my first post on this topic? It’s worth repeating:

Ideas like “Gothic,” “Renaissance,” or “Baroque”…can be used to characterize and interpret intellectual movements, but they express no actual historical facts that ever existed at any given time. “Renaissance” and “Middle Ages” are, strictly speaking, not names for historical periods at all…We cannot therefore use them as instruments for any strict division of periods; we cannot inquire at what temporal point the Middle Ages “stopped” or the Renaissance “began.” The actual historical facts cut across and extend over each other in the most complicated manner.

As I worked my way through the history of the world, I realized that the actual historical facts were leading me to the First Crusade as the end of my particular story. Constantine’s decision to march against Rome under the cross was the start of the story; his use of religion in warfare culminated with the First Crusade, which itself began a new tale.

I wouldn’t change anything about the book itself. But if I could do it again, I would have written a very clear preface, explaining exactly why I chose the starting and ending dates that I did. (In fact, I’ve asked Norton if I can insert a preface into future reprintings.)

And if I could go all the way back to the publication of the first book, I’d change the way the series is titled. I think I’d avoid using Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance altogether. The words are evocative–but for a world history, their limitations are greater than their benefits.

In the final post of this series, I’ll tell you why the Renaissance began in the twelfth century. And thanks to Victoria Kirkham and Armando Maggi, eds., Petrarch: A Critical Guide to the Complete Works for the Petrarch quotes.

February 27, 2013

Where in the world is Susan?

(Part Two of “When Did the Middle Ages End?” coming shortly! In the meantime…)

Anyone want to play Where in the World is Susan?

These should give you a pretty broad hint…but if you can’t figure it out I’ll post a few more.

(This one is “Where in the World is Susan’s Husband?”)

So what do you think?

ADDENDUM: You guys guessed it! Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. We’re here on a somewhat-delayed wedding anniversary trip. After a few too many wet, grey, muddy, nasty February days in Virginia, we’re loving the wind and the sun–not to mention the food and the scenery.

February 19, 2013

When Did the Middle Ages End and the Renaissance Begin? Part One of a Three-Part Reflection.

Late last spring, feeling punchy after way too many hours at the keyboard, I tossed off the following email to my esteemed editor:

Dear Star,

I have a new title idea. How about “There Is No Such Thing as the Renaissance: A History of the World from 1100 to 1500″?

s

p.s. This is my current favorite quote:

“Ideas like ‘Gothic,’ ‘Renaissance,’ or ‘Baroque’….can be used to characterize and interpret intellectual movements, but they express no actual historical facts that ever existed at any given time. ‘Renaissance’ and ‘Middle Ages’ are, strictly speaking, not names for historical periods at all….We cannot therefore use them as instruments for any strict division of periods; we cannot inquire at what temporal point the Middle Ages ‘stopped’ or the Renaissance ‘began.’ The actual historical facts cut across and extend over each other in the most complicated manner.” (Ernst Cassirer, “Some Remarks on the Question of the Originality of the Renaissance.”)

p.p.s. Completed ms will be with you by June 1. This time, I really mean it.

Starling Lawrence, who pays way too much attention to my occasional fits of irrationality, sent back an email asking whether that was really the title I wanted. (Actually, now that I look back at it, his exact words: “Were it not for those other two books, it isn’t absolutely crazy,” which might well be carrying the subtext, “This time you have really lost your mind.”)

In the end, we went with a title that was a little more compatible with the first two books in the series. But as I work my way through world history, it has become increasingly clear to me just how impossible, inaccurate, and misleading the traditonal Ancient Times/Middle Ages/Renaissance division is. And as I’ve written my way through the History of the World series, the slippage between the periods of history in the titles and the times that they are popularly supposed to cover became more acute.

It was least acute in The History of the Ancient World, for two reasons: first, “ancient” is popularly understood to mean “a long time ago” (a very flexible designation); and second, in terms of recorded history, the ancient world from Spain to the edges of the central Asian lands was folded into the history of the Roman Empire, and the trade routes even further east–so to call the same period in, say, northern India and in Rome “ancient” doesn’t really do violence to either of them.

But don’t forget that while the Roman empire and the Greeks and Egyptians were living through “ancient times,” many parts of the world–the Americas, much of Africa below the Sahara, the continent of Australia–were still in “prehistory,” the time before the written word. And since “ancient times” are traditionally separated from the “Middle Ages” by the collapse of Rome, neither term is all that accurate when applied to the Chinese and Japanese kingdoms–not to mention the dozens of smaller nations carrying on in the east and north and south, not paying the slightest bit of attention to Rome.

Even in Rome, the end of “ancient times” turned out to be less straightforward than I thought when I started writing. I had intended to carry the first volume through 476, the generally accepted “fall of Rome”: the date when the last “Roman emperor” was removed from the throne.

The problem? That’s not where the narrative I was writing ended.

The “last Roman emperor” wasn’t much of an emperor; he was a teenager recognized as ruler by Rome, first and foremost, by his ambitious father. Nor was he ruling in Rome; for some years, the “Roman empire” had been run from the swamp of Ravenna. Nor, for that matter, did he rule the Roman empire; only a very small part of Italy ever recognized him as a monarch. In some way, the end of Rome had come long before young Romulus Augustus abdicated.

As I wrote, it became clear to me that the end of the Roman story as I was telling it ended with Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. This, not the relatively pointless departure of Romulus Augustus from Ravenna, was the point at which the old Roman empire changed into something else.

So that’s where I ended The History of the Ancient World. And I guess I was pretty convincing, because only one reviewer ever commented on my choice of a stopping point, and then only in passing.

But this did not turn out to be the case with The History of the Medieval World, which covered the years between the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and the First Crusade. When I finished that manuscript, I was happy with the scope of the story. And I also thought that it would be perfectly clear to anyone who read it why I decided to choose 1100 as an ending point.

As it turned out…not so much.

Tune back in towards the end of the week and I’ll explain what I should have done instead. And then, in Part III of this series, I’ll tell you why The History of the Renaissance World begins in 1100 and ends in 1453.

January 25, 2013

More about Lance Armstrong. (And now I’m done.)

As I promised in my last post, I watched the second half of Lance Armstrong’s interview. And no, he didn’t change my mind.

What was he thinking? What were his handlers thinking? What was Oprah thinking?

To hear my answers…check out my interview with the wonderful Irish talk show host Tome Dunne and the slightly more academic half-hour discussion I had with religion journalist Mark Pinsky and radio host Maureen Fiedler.

January 18, 2013

Public grovelling. Again.

My 2008 book The Art of the Public Grovel has been making a bit of a reappearance in the last couple of days. Check out “America’s Confessor is Back in the Spotlight” (Oprah, not me, in case you’re wondering); “Coming Clean: Lance Armstrong and Forgiveness“; and “Lance Armstrong’s doping confession: An American ritual,” in the Washington Post. (Which you can also read in Russian, should you be so inclined.)

Public confession is rooted in American evangelicalism, and Americans have been willing to forgive famous wrong-doers as long as their admission follows a few rules, Susan Wise Bauer argued in her book “The Art of the Public Grovel.”

That it’s very public is one of them. Everyone wants to be able to witness it.

Another is that it can’t only express regret. The confession must be a clear statement of guilt, an admitted sin for which the person is sorry. Fall short of that, according to Bauer, and forgiveness is much less likely.

That’s the Kansas City Star, speculating on whether Lance Armstrong can pull off a successful comeback. Judging from his incoherent, dimwitted performance last night, I’m guessing not. But I plan to watch the second part of the interview tonight to see whether he manages–somehow–to change my mind.

January 10, 2013

The oldest and the youngest

January evening on the farm; my daughter and my father are fishing in the farm pond, right before sunset.

(My job was to build the fire. I like fire.)

December 19, 2012

When you’ve taught your kids at home for seventeen years…

…here’s what you’ve learned.

November 29, 2012

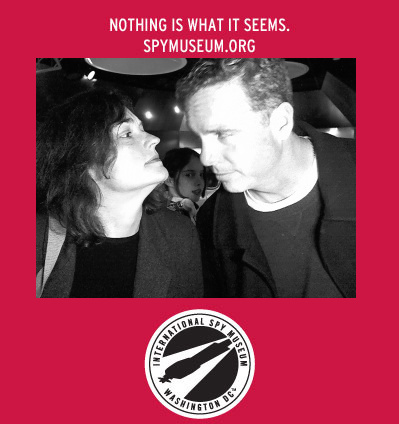

Especially not the sneaky little spy right behind you.

We’re in Washington, D.C. for a couple of days, doing field trips to museums with Emily and Dan.

I LOVE this picture. Totally unstaged–I mean, Pete and I are hamming it up, but we had no idea Emily was right behind us.

BE VERY CAREFUL. DENY EVERYTHING.

I wasn’t expecting much from the Spy Museum–we went by it after our morning at the Natural History Museum, inspecting dinosaur skeletons and gemstones–and so far it’s been the highlight of our trip. HIGHLY recommended.

November 26, 2012

New catalog page!

Check out the Norton catalog page for the History of the Renaissance World! My editor’s assistant just sent it along for me.

It’s up on the Norton website as well, linked to my Norton author page.

(Curious about what “Co-op available” means? So glad you asked that. Check out this entertaining explanation…)

November 4, 2012

First public outing(s)!

Much to my surprise, the History of the Renaissance World popped up on Amazon this week.

So I guess it’s real…

(Incidentally, the second level of Writing With Skill, our new pre-rhetoric series, appeared at the same time–it’s in beta-testing now,

and here’s the link to the accompanying Instructor Text.)

Susan Wise Bauer's Blog

- Susan Wise Bauer's profile

- 1089 followers