Susan Wise Bauer's Blog, page 9

April 7, 2012

Twitter Weekly Updates for 2012-04-08

Aww, she'd love to but she went to movies with Moll. Ask again though! #

Spent morning NOT working on Easter music & urgent deadlines, but chasing horses through neighboring fields with @melpmoore (in flip-flops). #

Animal control officer: "Are your horses out?" Point to all 4 innocently lounging in corral. Turns out he's looking for *other* loose horse. #

Powered by Twitter Tools

March 31, 2012

Twitter Weekly Updates for 2012-04-01

Highly important that you know this: http://t.co/xpD9NCoJ #

Powered by Twitter Tools

March 30, 2012

A preamble to the follow-up

In my post about best-laid plans, I said I was contemplating some new directions for my next writing project…and planning some other things as well.

Before I tell you about those "other things," I have to supply some historical background (which is appropriate enough, after all). So I'm going to give you a brief photo-essay for this preamble.

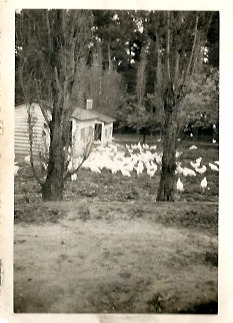

When my brother and sister and I were still toddlers, my father got out of the Navy and my parents moved back here, to the farm where my mother grew up. Back then, it was a chicken farm. Here are a few of the chickens, circa 1941. (For those of you who've followed my blog for a while, the nearer chicken house is now my office.)

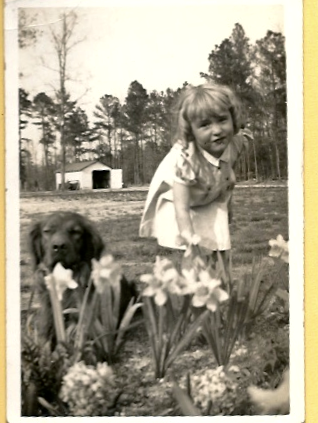

And here is my mother on the farm, circa 1941.

(Actually, this is my favorite picture from that decade, although it's not as clear. That's my mother on the left, in 1949, having just shot a possum. Yep, that's the possum.)

So the farm is where we grew up too. This is my brother with my mother's father, Papa Tench. My brother got to ride on the combine because he was a boy.

And here's my brother with my father, shortly after we moved back. As you can see, there were a number of things that were, er, guy territory. Although not possum-shooting, obviously.

And not grass cutting, because I got to do that too.

We raised hundreds of chickens, and we ate the eggs, and the chickens too. We raised pigs, and ate the pigs. We raised geese and ate the eggs (but not the geese.) We had a dairy cow named Taffy who ate the garden.

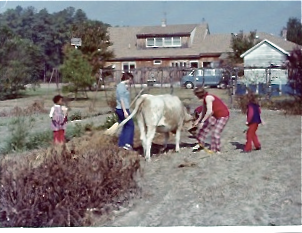

(My sister Deb on the left, me on the right, my mother with the grain bucket and the styling' pants. And yes, that is a Volkswagen van back there behind the grape arbor.)

We chopped our own wood and used it to heat the house.

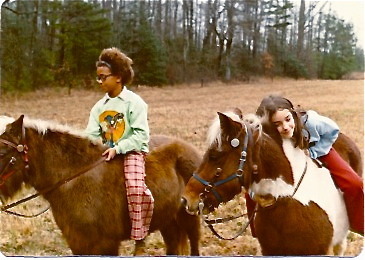

We rode our ponies everywhere.

(My sister will kill me for putting that photo up. For some reason, she thinks our seventies-era clothes are less than flattering.)

(My sister will kill me for putting that photo up. For some reason, she thinks our seventies-era clothes are less than flattering.)

We had acres of peach trees and apple trees and the world's most enormous garden.

(I'm not completely sure who all those people are, helping dig the potatoes. We had a lot of random people living on the farm in those days. One of them used to clog in the living room. Another one lived in a tent down near the chicken houses.)

We canned peaches, and froze peaches, and canned applesauce, and froze vegetables, and stored root vegetables. We didn't live entirely off the land. But we came close.

What does all this have to do with new directions? Stay tuned for the next post. In the meantime, you can admire our vintage farm-wear…

March 24, 2012

Twitter Weekly Updates for 2012-03-25

All I can say is…this never happens at the publishing company *I* own. http://t.co/HgR8b04L #

Man, I am *struggling* with the Sultanate of Delhi this morning. Me and the Rajputs, we have that in common. #

For the Renaissance, I need catastrophe synonyms. Ruination, wrack, devastation, dissolution, undoing, doom, obliteration, annihilation… #

Powered by Twitter Tools

March 21, 2012

A few of those details for you.

I spent the better part of a week rounding up contemporary chronicles that record this chunk of Welsh history, about the Welsh prince Llewellyn ap Gruffyd and his attempt to free Wales from the domination of the English king Edward I. But hey, the details make the story.

In November 1277, Llewellyn was forced to agree to a peace treaty, the Treaty of Conway, that took away from him everything but his original small northwest corner of Gwynedd. Edward I handed out Welsh lands to his barons in reward, took the Perfeddwlad for the crown, and gave Llewellyn's younger brother Dafydd the rule over a chunk of the Gwynedd principality that had once belonged to the older sibling.

But in five years, this arrangement fell apart. The English barons, as overlords to their Welsh tenants, were both dismissive and demanding; the English sheriff appointed to supervise Welsh affairs, Reginald de Gray, was harsh, dragging up decade-old offenses for trial and threatening petitioners with the death penalty; Dafydd himself was forced to obey English law in his own lands. "All Christians have laws and customs in their own lands," complained one Welsh nobleman. "Even the Jews in England have laws among the English; we had our immutable laws and customs in our lands, until the English took them away."

Just before Easter 1282, Dafydd rallied the Welsh princes behind him. The first act of war was the sudden attack on an English-held castle, Hawarden, on the Saturday night before Palm Sunday. Within a week, Llewellyn had joined his brother (the English were now a greater threat than his sibling's ambitions), and almost the entire country was in revolt.

This time, Edward I brought more men. Fighting in the north of Wales, fighting in the south of Wales: in December, the balance was still tipping rapidly back and forth between the sides. But on December 11, Llewellyn was ambushed by a band of English soldiers at a bridge crossing over the River Irfron. "Llewelyn ap Gruffydd is dead," wrote the commander of the ambush, in his report on the incident, "his army defeated, and all the flower of his army dead."

In fact, Llewelyn had only a small detachment with him; but with Llewelyn's fall, the Welsh resistance lost its heart. Dafydd immediately declared himself Llewellyn's succesor as Prince of Wales and carried on the fight, but in June of 1283 he was turned over to the English by a handful of his own companions.

The war had been expensive and vexing, and Edward authorized a new punishment for Dafydd. He was drawn, hung, and quartered, a barbaric punishment carried out on a still-living rebel: dragged through the streets of London behind a horse, as a traitor; hung as a thief; and then cut down when still alive, disembowelled and his intestines burnt in front of his eyes, an ancient penalty for homicide. Finally, says the contemporary Chronicle of Lanercost, "his limbs were cut into four parts as the penalty of a rebel, and exposed in four of the ceremonial places in England as a spectacle." His right arm went to York, his left to Bristol, his right leg to Northampton, his left to Hereford. His head, bound in iron to keep it from falling apart as it decayed, was stuck on a spear shaft at the Tower of London.

Edward then took the title Prince of Wales for himself. The 1284 Statute of Rhuddlan formally added Wales to the English empire. Llewellyn became known as Llewellyn the Last; Wales would never again have an independent ruler.

I guess not; those decaying arms and legs must have put quite a few potential Welsh rebels off the idea of defying the English.

March 19, 2012

Best-laid plans, and all that.

I haven't made too many blog posts recently.

I used to post a lot more. About the writing process and about what I read in my spare time and about all the things that get in the way of work. Actually, a lot of that.

And about my other ongoing responsibilities for previous books and my publicity travel and the photos on the covers of my books and the book business from a writer's point of view and the things that get in the way of writing. And about NOTHING AT ALL, when I felt like it.

For the last six months or so, I haven't really blogged at all. So now I'm going to tell you why.

BECAUSE WRITING THE HISTORY OF THE WHOLE WORLD IS A FULL-TIME JOB.

Let me "nuance that," as one of my least favorite lit professors used to say: Writing the history of the world is a job that becomes more and more consuming with time, until there is nothing left but a huge stack of primary resources and an Everest-sized pile of secondary research that Must. Be. Looked. At. Or else you'll miss something that everyone in the world but you knows.

("I don't know if you've realized this," remarks Starling Lawrence, my esteemed and sometimes-compassionate editor at Norton, "but this project is wearing on you." Or words to that effect. Uh huh, I had indeed noticed that.)

Let me recap.

Ten years ago, I started writing the History of the Entire World. This was a project that grew out a children's world history series I wrote, The Story of the World. And that was a project that grew out of the 1999 book on classical education that my mother and I co-authored: I couldn't find any world history resources I liked, so I wrote my own.

The Story of the World series did very well, and so one day my editor called me and said, "You know, I snagged a copy of The Story of the World from the mailroom and I've been reading it. This is very good!"

Me: Er, thanks.

SL: Have you thought about writing one for adults?

Me: A history book?

SL: Yes, a history of the world.

Me: You mean the whole world?

SL: Yes, of course.

Me: In one volume?

SL: No, in four volumes.

Me [thinking that it took Will Durant something like 28 years to do this]: A four-volume history of the world? Well…

SL: Fine, write a letter telling me how you'd do it and we'll take it from there.

So I called my agent and said, "Star Lawrence thinks I should write a history of the world."

Agent: The whole world?

Me: Er, yes.

Agent: Sounds like a great idea. Good follow up to the last book. How long would it take you?

Me [having no idea]:…Eight years?

Agent: OK, send me a letter telling me how you'd do it and I'll take it up with Norton.

So then I go talk to my husband.

Me: My agent and Star Lawrence think I should write a history of the world.

Husband: The WHOLE world?

Me: Yes.

Husband: Cool.

Me: It'll take eight years. At least.

Husband: Is that all?

Well, no, not exactly. The original contract for the History of the World series had, I think, a much briefer and breezier kind of history in mind, a Story of the World for grown-ups that had more detail, of course, but the same tone as the kid's series.

The problem was: I couldn't do it that way.

When I started writing, I wanted answers to all the questions I had always asked myself. Like: When we say that an "empire fell," what does that mean, exactly? How did happen? Who did it?

Or: If a medieval country "became Christian," does that mean that everyone was baptized, or just the king, or just the aristocracy? And if the latter, how exactly did the king convince them? And what was the king's name? And why did he do it? And who were the aristocrats, anyway?

Or: If the peasants revolted, which ones started it? Why did the revolt reach critical mass instead of fading away? Who corralled all the rebels and got them to march in the same direction? Why did he do it? Were they hungry? If they were, how much did a bushel of wheat cost? What is that in contemporary U.S. dollars?

I needed to know these things. Kids need a general survey; they need a structure, an outline, a scaffolding to build on. I'm a grown-up. I needed to know why. Why meant who, how, where, on what day. "Corroborative detail is the great corrective," wrote the amazing narrative historian Barbara Tuchman, in a quote I have parked on my home page. "It forces the historian who uses and respects it to cleave to the truth."

I love finding corroborative detail. All at once, generations of the long-dead come to life. And speak (so not in a creepy Walking Dead kind of way. Yes, I'm an addict. But never mind that).

It takes an enormous amount of time to find corroborative detail. I have spent entire days tracking down a single bit of the past (the day a rider started out from Point A, headed for Point B; the weather at the moment a fleet launched; the exact price paid for a ransom) that doesn't even make it into the final book; but a detail that I needed to know, or else the story wouldn't make sense to me.

I love doing this. But it didn't take eight years for four books; it took ten (so far) for two.

There's only so much detail about Sumer in the third millennium. Frankly, there's only so much detail about the Roman empire. Or about ninth-century Germanic tribes stomping around near the Rhine. But the detail starts to ramp up sharply around the end of the first millennium. And from then on, recorded history expands outwards, like the blast radius of an ever-growing explosion.

It's no coincidence the the History of the Ancient World, covering over five thousand years of recorded history, and the History of the Medieval World, covering seven hundred years, are the same length.

So I've been running constantly up against two problems.

The first is a research problem. I have to know the details; otherwise I don't know which ones fit into the particular story I'm telling. I have to find out exactly what happened before I can write a summary. Relying on the summaries of others is a stop-gap solution; you can't do it often before you've lost any sense of the time itself. So it is taking me longer, and longer, and longer to sort through the ever-expanding written resources and figure out what I need to use. It took me three years to write the history of five millennia. It's taken me three years to write the history of four centuries. This is only going to get more complicated. By the time I get to the twentieth century, I'll be finishing off one decade per year. If that.

The second is a consistency problem.

This third volume–of what was originally meant to be a four-volume series–was supposed to cover 1100 through 1700 A.D. It's become increasingly clear to me that it can't, not in a way that sounds consistent with the first two volumes, at the same length. To keep on with the pattern I established with the Ancient World and the Medieval World, this volume would have to be…um…fifteen hundred pages long.

Or else suddenly turn into a breezy surface survey, very unlike what came before.

This problem will only get more acute. If I try to do the fourth volume, 1700 to the present, on the same pattern, do you know how many pages I'll have to do all of World War II?

Four. Yep, that's right. Four.

I can't do World War II in four pages, and I can't imagine that the readers who've enjoyed the first volumes will find it even the tiniest bit satisfying. There's just too much detail: too much they already know; too many lives already recorded that must be paid the proper respect.

We started out this project by imposing a structure on the material. It won't work. The material itself–the history of the world–won't be contained. It keeps bursting out.

So what's the solution?

If you're very alert, you might have noticed that, a week or so ago, the description of this blog changed from "my progress as I write…a four-volume history of the world" to "my progress as I write…a multi-volume history of the world." (Yeah, don't worry about it, I didn't really think anyone would notice.)

The always-supportive folks at Norton have agreed to a restructuring of the contract. First, the current volume–the one I'm trying to finish up now–will be the History of the Renaissance World, and it will cover from the end of the First Crusade to the end of (you guessed it) the Renaissance–which, in my view, is when Vasco da Gama rounds the Cape (stay tuned for more on this). That's four hundred years, 1100-1500. That's eight hundred pages, in tune with the first two volumes.

So my kind readers will then have three parallel volumes to enjoy: The History of the Ancient World, The History of the Medieval World, and the History of the Renaissance World.

What comes next?

I'm not sure yet. I have to stop and think. The Renaissance is the last easily-defined historical period, the last one on which there's wide agreement among writers that yes, this may be an inaccurate name, but it's a useful way to designate a period of the past. After the Renaissance, there's Exploration, Discovery, Colonization, Reformation, Early Modern. It's a free-for-all, and that's just the west; none of those labels work east of the Oxus River anyway.

The material needs to dictate the form of the book, not the other way around. When I finish the History of the Renaissance World (which will happen very shortly), I will now get to stop. And think. And breathe. And read. In the last two years, I've read four or five books per week, at the hyper-speed developed by my academic training and demanded by my current writing pace. That's fine, but it doesn't allow for a lot in the way of creative thought. You become a pragmatic reader, not a curious one; a utilitarian reader.

So that's the plan. I'm going to take a breath.

I'm not going to stop writing. Oh, no. There are SO MANY THINGS I want to write. They just aren't fitting, neatly, into a four-volume-history-of-the-world format. They spring off into all sorts of fascinating and untidy directions.

And there are a couple of other things I'm planning on as well. Check back a little later this week, and I'll tell you all about it.

In the meantime…if you haven't read about the ancient and medieval worlds, what are you waiting for? Go forth and do so. The History of the Renaissance World is about to descend upon you. (I think.)

March 10, 2012

Twitter Weekly Updates for 2012-03-11

Heading to Oklahoma City on a sunny morning. Feel like there's already a country song about this. #

Dear Colts: With all that money you're saving, couldn't you have hired Jim Irsay a speechwriter? #

Can't really express the sense of personal loss I feel at this news: http://t.co/zcZokUI0 #

Yesterday's sunny morning in Oklahoma has turned into today's 36-degree howling gale. #

TSA#1 to TSA#2, post-scanner: "Check her right shoulder." TSA#2: (pats my left shoulder) "She's OK." Question: Point out error? Or run away? #

Powered by Twitter Tools

March 3, 2012

Twitter Weekly Updates for 2012-03-04

Google nearly starts a war: http://t.co/IxlwBvu1 #

Today's chapter in the History of the Renaissance World finally coming together, but only title I can think of is "Total Chaos Everywhere." #

Getting ready to depart for my first 2012 conference. A changing-of-the-seasons sign, like the first frost or first crocus. Or something. #

Powered by Twitter Tools

February 29, 2012

Reason #378 why grammar is important

From this morning's batch of email…

Good afternoon,

Here with the Better Business Bureau would like to inform you that we have received a complaint (ID 59162843) from a customer of yours in regard to their dealership with you.

Please open the COMPLAINT REPORT attached to this email (open with Internet Explorer/Firefox) to view the details on this issue and suggest us about your position as soon as possible.

We hope to hear from you shortly.

Regards,

KAMALA PAIGE

Dispute Counselor

Better Business Bureau

Oh, absolutely! Let me open that attachment right away!

Dear spammer: If only you had studied grammar with a good thorough handbook that included subject/verb and antecedent/pronoun agreement, the difference between indirect and direct objects, thesaurus use, and maybe even diagramming, you'd sucker a whole lot more people in.

Good grammar continues to be important. Even in the information age.

February 25, 2012

Twitter Weekly Updates for 2012-02-26

Sure! #

Checking through DD11's work, I find that she wrote me a note: "I acedentaly did too much spelling today." Apparently not. #

German shepherd went nose-to-nose with a skunk.We scrubbed him down with soap and vinegar; now he smells like a giant pickled skunk cabbage. #

Monday: Snow. Hot chocolate. Sleds. Icicles. Friday: 81 degrees. Thunderstorms. Gusty winds. I'm disoriented. The horses look confused too. #

"Many lettuces contain lactucarium ('lettuce-opium'), a mild analgesic and sedative that can generate a…sense of euphoria." Huh. #

German shepherd just went nose-to-nose with skunk for SECOND time this week, THIRD time this year. It's like having another teenager. #

Powered by Twitter Tools

Susan Wise Bauer's Blog

- Susan Wise Bauer's profile

- 1089 followers