Kelly McCullough's Blog, page 26

July 27, 2013

Reviews

In the theory that a blog should have pretty frequent posts, I am posting again.

I got another review of Big Mama Stories at Strange Horizons. All the reviews thus far (two in Locus, one at Tor.com, plus Strange Horizons) say the stories are a tad bit too didactic, though the reviews are mostly positive.

I mentioned this to my brother. He said, "The stories are what they are. If people don't like this kind of story, they won't like these." Which I thought was a nifty way to describe the book.

There is also a nice and intelligent reader's review at Amazon.

Do reviews matter? They matter to me. I pay attention to recommendations from reviewers I respect, and I pay attention to blurbs by writers I respect.

The next question is, what is wrong with didactic? There is a long tradition of stories with morals. AEsop's Fables, for example. Fairy tales and folk tales can be anarchic, as in trickster stories. They can also have straightforward morals. Be kind of old people and animals, especially if the animals can talk.

I got another review of Big Mama Stories at Strange Horizons. All the reviews thus far (two in Locus, one at Tor.com, plus Strange Horizons) say the stories are a tad bit too didactic, though the reviews are mostly positive.

I mentioned this to my brother. He said, "The stories are what they are. If people don't like this kind of story, they won't like these." Which I thought was a nifty way to describe the book.

There is also a nice and intelligent reader's review at Amazon.

Do reviews matter? They matter to me. I pay attention to recommendations from reviewers I respect, and I pay attention to blurbs by writers I respect.

The next question is, what is wrong with didactic? There is a long tradition of stories with morals. AEsop's Fables, for example. Fairy tales and folk tales can be anarchic, as in trickster stories. They can also have straightforward morals. Be kind of old people and animals, especially if the animals can talk.

Published on July 27, 2013 11:12

July 21, 2013

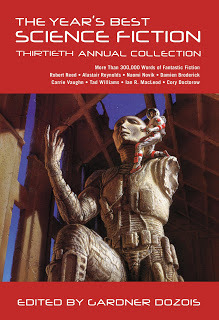

Story! Picture!

This goes on sale July 23, and it contains one of my stories, a hwarhath Sherlock Holmes story. Dozois puts together a good anthology, so you might be interested in getting the book.

This goes on sale July 23, and it contains one of my stories, a hwarhath Sherlock Holmes story. Dozois puts together a good anthology, so you might be interested in getting the book.I don't usually self-promote. Not much, anyway. But Dozois is recruiting authors to spread the word. Since he buys my stories, I want his anthologies to do well.

Published on July 21, 2013 07:16

July 18, 2013

Whales and Plot and Peer Review

Yesterday's class was meant to cover plot... we sort of meandered through the idea, but here's much of what happened:

First of all, a young lady from my class came up afterwards to tell me about this: http://blogs.discovery.com/animal_news/2012/05/52-hertz-the-loneliest-whale-in-the-world.html A whale who, apparently due to an accident at birth, sings at a frequency (52 hertz) that others of her kind can't hear. She's been alone her whole life and growing despondent. Just thinking about this whale makes me cry, but, as this person pointed out, it's another whale fact that could potentially wrap into the my story seed.

After the great involvement of the cliché discussion I was anticipating a bit of what I call the "Bejeweled Blitz" phenomenon. The Blitz phenomenon is this: I used to play this iPad game that I could, occasionally, through a combination of practice and luck, score crazy high scores on. I'd hit one awesome one and the next one was not only never as good, but so bad it was almost embarrassing.

Class wasn't that bad. Because I've finally gotten the students willing to just talk to me (teenagers, think about this miracle, people!), we managed to wrestle out some thoughts about plot. Plot, according to them, is what they struggle with more than anything. So, we talked some basics. I reminded them that, while people like to say so, plot is NOT "the action of the story." If that were true there'd be no such thing as a "gratuitous fight scene." Yet we've all read them. Plot is much, much more than "the things that happen."

Plot is forward motion on theme. That last bit is critical. Plot has to answer the story's question, the what if? Or the 'will the alien invasion/zombie apocalypse be successful?' or 'will her boss find out about the affair?' Or whatever is the pressing question that reflects the story's main theme.

Plot isn't always big. It isn't always the wham-bam action. Sometimes it's the idea that hits our heroine while she's brushing her teeth THAT CHANGES EVERYTHING.

So, while I'm not sure I left my students with any tools to achieve that, I tried to explain that pacing and plot are so intertwined that it's almost impossible to separate them. If your pacing is off, it means your characters aren't addressing plot. Yes, they need sleep and downtime, but that doesn't mean plot isn't happening. You can create plot with the sense of the shoe ready to drop. If your readers have the plot question hanging over their heads (with worry!) and the scenes you write expand on theme, your pacing will never lag, even if, as a writer, you're sure it is.

My friend Josey I talk about this all the time, because sometimes you have to slow down a story to explain a part of world-building in order for the action to make sense. It's easy to get bogged down in details of politics, economics, etc., particularly in SF/F since often that's the part of the story that really turns the WRITER on. My sense is that the trick to including those moments without losing precious pacing/reader's patience is remembering what the reader is worried about and putting in reminders that your characters haven't forgotten either. The thing that's looming (will anyone notice that our hero has slipped out into the night... coupled with worry as a reader, since the consequences for being caught are so huge...) you can do your travel or whatever needs explaining. Especially if (and this is heavy-handed example) our hero occasionally checks the time and does a risk analysis, ie. "I can spend ten more minutes, can't I?" Because the reader, if you've laid your groundwork properly, should be shouting at the screen/page, "NO YOU CAN'T, YOU MORON, HE'S RIGHT ON YOUR HEELS!!" and thus tension, plot and pacing are created/maintained.

At least that's one theory.

The majority of the class was taken up by critique, because I'm insane... no, the thing is I truly believe in the power of peer review. It's important for the authority figure (me) to doll out praise and advice, but it's rewarding, IMHO, for the students who are critiquing to hear how their opinions might differ from the teachers and for the student being critiqued to hear patterns--because when everyone to a person says, "needs more description here," most people figure out that's a good indication that more description is needed there.

My students made me proud by being civil and communicative. I've decided that everything people say about teenagers is a lie. Or maybe nerd/geek/otaku kids are just my people, no matter what age.

First of all, a young lady from my class came up afterwards to tell me about this: http://blogs.discovery.com/animal_news/2012/05/52-hertz-the-loneliest-whale-in-the-world.html A whale who, apparently due to an accident at birth, sings at a frequency (52 hertz) that others of her kind can't hear. She's been alone her whole life and growing despondent. Just thinking about this whale makes me cry, but, as this person pointed out, it's another whale fact that could potentially wrap into the my story seed.

After the great involvement of the cliché discussion I was anticipating a bit of what I call the "Bejeweled Blitz" phenomenon. The Blitz phenomenon is this: I used to play this iPad game that I could, occasionally, through a combination of practice and luck, score crazy high scores on. I'd hit one awesome one and the next one was not only never as good, but so bad it was almost embarrassing.

Class wasn't that bad. Because I've finally gotten the students willing to just talk to me (teenagers, think about this miracle, people!), we managed to wrestle out some thoughts about plot. Plot, according to them, is what they struggle with more than anything. So, we talked some basics. I reminded them that, while people like to say so, plot is NOT "the action of the story." If that were true there'd be no such thing as a "gratuitous fight scene." Yet we've all read them. Plot is much, much more than "the things that happen."

Plot is forward motion on theme. That last bit is critical. Plot has to answer the story's question, the what if? Or the 'will the alien invasion/zombie apocalypse be successful?' or 'will her boss find out about the affair?' Or whatever is the pressing question that reflects the story's main theme.

Plot isn't always big. It isn't always the wham-bam action. Sometimes it's the idea that hits our heroine while she's brushing her teeth THAT CHANGES EVERYTHING.

So, while I'm not sure I left my students with any tools to achieve that, I tried to explain that pacing and plot are so intertwined that it's almost impossible to separate them. If your pacing is off, it means your characters aren't addressing plot. Yes, they need sleep and downtime, but that doesn't mean plot isn't happening. You can create plot with the sense of the shoe ready to drop. If your readers have the plot question hanging over their heads (with worry!) and the scenes you write expand on theme, your pacing will never lag, even if, as a writer, you're sure it is.

My friend Josey I talk about this all the time, because sometimes you have to slow down a story to explain a part of world-building in order for the action to make sense. It's easy to get bogged down in details of politics, economics, etc., particularly in SF/F since often that's the part of the story that really turns the WRITER on. My sense is that the trick to including those moments without losing precious pacing/reader's patience is remembering what the reader is worried about and putting in reminders that your characters haven't forgotten either. The thing that's looming (will anyone notice that our hero has slipped out into the night... coupled with worry as a reader, since the consequences for being caught are so huge...) you can do your travel or whatever needs explaining. Especially if (and this is heavy-handed example) our hero occasionally checks the time and does a risk analysis, ie. "I can spend ten more minutes, can't I?" Because the reader, if you've laid your groundwork properly, should be shouting at the screen/page, "NO YOU CAN'T, YOU MORON, HE'S RIGHT ON YOUR HEELS!!" and thus tension, plot and pacing are created/maintained.

At least that's one theory.

The majority of the class was taken up by critique, because I'm insane... no, the thing is I truly believe in the power of peer review. It's important for the authority figure (me) to doll out praise and advice, but it's rewarding, IMHO, for the students who are critiquing to hear how their opinions might differ from the teachers and for the student being critiqued to hear patterns--because when everyone to a person says, "needs more description here," most people figure out that's a good indication that more description is needed there.

My students made me proud by being civil and communicative. I've decided that everything people say about teenagers is a lie. Or maybe nerd/geek/otaku kids are just my people, no matter what age.

Published on July 18, 2013 05:04

July 16, 2013

Ideas and Cliches

I had my second class at the Loft today, and what I told Shawn after she asked about how it went: you never can tell what's going to hit.

Our official topic was "Where Do You Get Your Crazy Ideas?" but, luckily, while I was gathering things up for class and looking for a print-out of Neil Gaiman's Idea essay, it occurred to me that, when I was fifteen, ideas were NOT the problem. So, impulsively, I grabbed my trusty list of science fiction and fantasy clichés, thinking that we could segue into that, if necessary. I also grabbed some index cards in case we had time to play an idea-generating game.

But, trying to stay faithful to what I'd promised to talk about, I started out by reading Neil's essay. I adore this. If you've never read it, you should: http://www.neilgaiman.com/p/Cool_Stuff/Essays/Essays_By_Neil/Where_do_you_get_your_ideas%3F" It's charming and brilliant, and it set a good tone for the class.

I tried after we read that to engage people in a discussion about where THEIR ideas came from. My little zombie sullen youth stared blankly back at me. So, I switched tracks. I told them about an idea "seed" of mine that's never, EVER worked. What it is, is a collection of cool facts. Certain whale songs (humpback) get longer every year. My "what if?" is: What if this is the mythic retelling of how whales chose to return to the water, despite having lived on land long enough to develop lungs. It gets longer every year, because it's a kind of folk tale that gets retold and embellished. Fact number two: there used to be a whale that attempted to swim up-river in Sacramento every year, and had to be driven back to the safety of salt water. Are these events connected? Is there a whale prophet/explorer, attempting to return to the mythical land of her/his ancestors?

That's the gist of it. I've had this story in my head for DECADES and have never pulled anything useful out of it, so I asked for their help (while sneakily discussing elements you need to consider when you start to flesh out a story.) So, I asked them, who can tell this tale? A whale, probably, but a whale a good narrator? My problem has always been that a whale narrator is FAR too alien. Whales, if you think about it, live in an environment hostile to them, in which they can't breathe and are in constant danger of drowning. To breathe and survive, they have to stick their heads out of their environment into an utterly baffling, strange OTHER PLACE, where they catch glimpses of creatures with wings, boats, and... land.

I've always maintained that to write well from a whale's perspective, you'd end up having to invent so much world-building, culture and backstory that the whales would not be relatable any more. So who else could tell the tale?

Then, we discussed whether or not, if I chose a woman who was descendant from a whale who chose to stay on land and thus could telepathically talk to whales, this was enough to have a story? No, we decided it needed to be about something. Something needed to happen. I jumped on my favorite set of story questions which generate, often, the conflict of the story (which I always maintain must be two-fold: external AND internal) which is: What's at stake for the main character? What are they risking? What do they have to lose?

Now, I would have thought this was the meat of the class. I did manage to get some buy-in, but when I saw eyes starting to glaze I switched over to SF/F clichés. OH MY GOD, this was the thing that got everybody hopping. My theory is that at 15 - 17 is when you really begin to develop taste as a reader. Mason, right now, devours everything in sight. He doesn't really filter for quality or story telling expertise. It just has to be in his hands. I think by the age of my class, people are really starting to form serious, informed decisions about plot and character and storytelling as a craft. So the idea of clichés in the books that bugged them, really got some serious involvement. I also related the idea of clichés back to our discussion of story generation. Is it okay to use clichés? It is. If you know what you're using and use it wisely. You can even generate story ideas by INTENTIONALLY SUBVERTING CLICHES.

So, a good class. We got so wound up shouting out different clichés that we never played our story game. I have no idea if my students will find a game like the one I was planning helpful or groan-worthy. Given that it's basically set up for adults who need idea prompts, probably the latter.

Since today went so well, I totally expect tomorrow to be a monumental fail...

Our official topic was "Where Do You Get Your Crazy Ideas?" but, luckily, while I was gathering things up for class and looking for a print-out of Neil Gaiman's Idea essay, it occurred to me that, when I was fifteen, ideas were NOT the problem. So, impulsively, I grabbed my trusty list of science fiction and fantasy clichés, thinking that we could segue into that, if necessary. I also grabbed some index cards in case we had time to play an idea-generating game.

But, trying to stay faithful to what I'd promised to talk about, I started out by reading Neil's essay. I adore this. If you've never read it, you should: http://www.neilgaiman.com/p/Cool_Stuff/Essays/Essays_By_Neil/Where_do_you_get_your_ideas%3F" It's charming and brilliant, and it set a good tone for the class.

I tried after we read that to engage people in a discussion about where THEIR ideas came from. My little zombie sullen youth stared blankly back at me. So, I switched tracks. I told them about an idea "seed" of mine that's never, EVER worked. What it is, is a collection of cool facts. Certain whale songs (humpback) get longer every year. My "what if?" is: What if this is the mythic retelling of how whales chose to return to the water, despite having lived on land long enough to develop lungs. It gets longer every year, because it's a kind of folk tale that gets retold and embellished. Fact number two: there used to be a whale that attempted to swim up-river in Sacramento every year, and had to be driven back to the safety of salt water. Are these events connected? Is there a whale prophet/explorer, attempting to return to the mythical land of her/his ancestors?

That's the gist of it. I've had this story in my head for DECADES and have never pulled anything useful out of it, so I asked for their help (while sneakily discussing elements you need to consider when you start to flesh out a story.) So, I asked them, who can tell this tale? A whale, probably, but a whale a good narrator? My problem has always been that a whale narrator is FAR too alien. Whales, if you think about it, live in an environment hostile to them, in which they can't breathe and are in constant danger of drowning. To breathe and survive, they have to stick their heads out of their environment into an utterly baffling, strange OTHER PLACE, where they catch glimpses of creatures with wings, boats, and... land.

I've always maintained that to write well from a whale's perspective, you'd end up having to invent so much world-building, culture and backstory that the whales would not be relatable any more. So who else could tell the tale?

Then, we discussed whether or not, if I chose a woman who was descendant from a whale who chose to stay on land and thus could telepathically talk to whales, this was enough to have a story? No, we decided it needed to be about something. Something needed to happen. I jumped on my favorite set of story questions which generate, often, the conflict of the story (which I always maintain must be two-fold: external AND internal) which is: What's at stake for the main character? What are they risking? What do they have to lose?

Now, I would have thought this was the meat of the class. I did manage to get some buy-in, but when I saw eyes starting to glaze I switched over to SF/F clichés. OH MY GOD, this was the thing that got everybody hopping. My theory is that at 15 - 17 is when you really begin to develop taste as a reader. Mason, right now, devours everything in sight. He doesn't really filter for quality or story telling expertise. It just has to be in his hands. I think by the age of my class, people are really starting to form serious, informed decisions about plot and character and storytelling as a craft. So the idea of clichés in the books that bugged them, really got some serious involvement. I also related the idea of clichés back to our discussion of story generation. Is it okay to use clichés? It is. If you know what you're using and use it wisely. You can even generate story ideas by INTENTIONALLY SUBVERTING CLICHES.

So, a good class. We got so wound up shouting out different clichés that we never played our story game. I have no idea if my students will find a game like the one I was planning helpful or groan-worthy. Given that it's basically set up for adults who need idea prompts, probably the latter.

Since today went so well, I totally expect tomorrow to be a monumental fail...

Published on July 16, 2013 20:57

July 15, 2013

Yeah, let's call it "Organic..."

I think I have what could be called an “accidental” teaching style, which is to say, if I teach anything of substance, it’s entirely by accident.

Or... organic. Yeah, let's say "organic."

Today was the first day of my week-long class “More Than the Zombie Apocalypse: Writing SF/F” for teens at the Loft as part of their Youth Summer program.

I started off the class with the question I love to start with which is by the opening gamut: “What is science fiction? How is it different from fantasy?” We actually spent the majority of the class untangling this classic question. I tried to hit on several ideas in my usual round-about way.

1. A science fiction story’s plot turns on a science concept (math, physics, biology, etc.) and a fantasy story’s plot turns of magic or myth. This is the definition that I usually prefer for myself. Of course, by this definition my novel Archangel Protocol which says “science fiction” right there on the spine is actually fantasy. No science turns the plot; angels do. Thus: fantasy. However, this is often a pretty good rule of thumb. This also encompasses one of the student’s idea that it’s fantasy if there’s magic in it, and science fiction if there’s technology and/or tech that could be mistaken as magic (Clarke’s Third Law) in it.

2. It’s science fiction (or fantasy) if it FEELS like it. That’s to say, that sometimes it’s utterly subjective. If a story’s background takes place in the future, it’s science fiction, because even if the future has elves, somehow the addition of ray guns and space ships automatically means SF.

3. It’s science fiction (or fantasy) because a science fiction author wrote it. Sometimes you come across stories in SF/F magazines that seem like neither SF or F, they might be there because someone who wrote it is known to the SF/F community. Another interesting side note about this is that some subgenres tend to get placed in on one side of the dividing line or the other because of where they came out of. Our example: steampunk. It came out of an SF tradition, therefore it’s SF.

4. It’s fantasy (or science fiction) because that’s what it says on the book spine. We didn’t entirely cover this directly, but, in passing, I mentioned that none of this really matters except when you want to find a publisher. It’s helpful to be able to tell an agent or an editor, I wrote x (and fill-in what genre/subgenre you wrote.) It’s also helpful when you want to find more books like the ones you enjoy as a reader (which is why it’s important to the publisher). We never talked about this last part officially, but we did have a side conversation about what kind of books we looked for, ie hard versus soft SF.

Speaking of hard and soft, we spent a lot of time talking about the various subgenre’s of SF/F and where they fell on the spectrum: high and low fantasy, contemporary/urban fantasy, quest fantasy, and grimdark/dark fantasy. In SF: cyberpunk, steampunk, hard and soft SF, far-future and near-future, space opera, and science fantasy. We debated about where time-travel and superhero stories fit into all this. We also had a category for “straddles both.”

I took a few questions from the students when we seemed to run out of steam. There was an interesting one about how do you merge two divergent characters into a single storyline. I didn’t have a good answer for that per se, but I used the question to talk about when you start a story (just before everything changes) and some of my theories about how a novel and a short story should be structured in terms of increasing external pressure and mounting personal/emotional stakes.

That led a discussion about books that failed to start just before everything changes but were still popular, most notably Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s/Philosopher’s Stone.

I ultimately said that my answer to writing two divergent storylines coming together was that you needed to do it carefully and to show similar progression in the emotional arcs or the external pressure arcs of the separate characters.

Another student wanted to know how to write a dystopia masquerading as a utopia, which sounded marvelous to me. I brought up Mussolini, and suggested that one way was to show trains running on time. The idea being that if a dystopia has the feeling of clean efficiency it’s easy to mistake it for a utopia. I reminded the student that he needed to be sure to have his p.o.v. character be observant enough to give the reader clues that ‘something’s NOT right,’ even if it’s something like a noticeable military presence coupled with a sense of unease—someone else threw out the idea that a big brother mindset could work. The idea there being that if you show faulty logic as part of the world-building (if you do it in a way that’s not so clumsy people think you’ve made the mistake), you can imply a grim underbelly. I feel, however, we could have done a whole hour and a half class on that question.

I have no idea if my disorganized, jumbled teaching style will work for any of these students, but I have hope. I was impressed by how many of them are actively engaged in writing short stories or novels. In an adult class of the same size, it’s not uncommon to only have half the people actively writing something. In this class, it was 90%. That makes thing easier for me, because often that mean that people have, as shown above, very specific needs that can be met and questions that can be answered.

But, despite all that, I managed to have volunteers for critique. They have to have (no more than, but anything up to) 10 pages of something ready to hand out tomorrow. I got six people ready to go. If even half of them follow-through, that’s a great start.

Or... organic. Yeah, let's say "organic."

Today was the first day of my week-long class “More Than the Zombie Apocalypse: Writing SF/F” for teens at the Loft as part of their Youth Summer program.

I started off the class with the question I love to start with which is by the opening gamut: “What is science fiction? How is it different from fantasy?” We actually spent the majority of the class untangling this classic question. I tried to hit on several ideas in my usual round-about way.

1. A science fiction story’s plot turns on a science concept (math, physics, biology, etc.) and a fantasy story’s plot turns of magic or myth. This is the definition that I usually prefer for myself. Of course, by this definition my novel Archangel Protocol which says “science fiction” right there on the spine is actually fantasy. No science turns the plot; angels do. Thus: fantasy. However, this is often a pretty good rule of thumb. This also encompasses one of the student’s idea that it’s fantasy if there’s magic in it, and science fiction if there’s technology and/or tech that could be mistaken as magic (Clarke’s Third Law) in it.

2. It’s science fiction (or fantasy) if it FEELS like it. That’s to say, that sometimes it’s utterly subjective. If a story’s background takes place in the future, it’s science fiction, because even if the future has elves, somehow the addition of ray guns and space ships automatically means SF.

3. It’s science fiction (or fantasy) because a science fiction author wrote it. Sometimes you come across stories in SF/F magazines that seem like neither SF or F, they might be there because someone who wrote it is known to the SF/F community. Another interesting side note about this is that some subgenres tend to get placed in on one side of the dividing line or the other because of where they came out of. Our example: steampunk. It came out of an SF tradition, therefore it’s SF.

4. It’s fantasy (or science fiction) because that’s what it says on the book spine. We didn’t entirely cover this directly, but, in passing, I mentioned that none of this really matters except when you want to find a publisher. It’s helpful to be able to tell an agent or an editor, I wrote x (and fill-in what genre/subgenre you wrote.) It’s also helpful when you want to find more books like the ones you enjoy as a reader (which is why it’s important to the publisher). We never talked about this last part officially, but we did have a side conversation about what kind of books we looked for, ie hard versus soft SF.

Speaking of hard and soft, we spent a lot of time talking about the various subgenre’s of SF/F and where they fell on the spectrum: high and low fantasy, contemporary/urban fantasy, quest fantasy, and grimdark/dark fantasy. In SF: cyberpunk, steampunk, hard and soft SF, far-future and near-future, space opera, and science fantasy. We debated about where time-travel and superhero stories fit into all this. We also had a category for “straddles both.”

I took a few questions from the students when we seemed to run out of steam. There was an interesting one about how do you merge two divergent characters into a single storyline. I didn’t have a good answer for that per se, but I used the question to talk about when you start a story (just before everything changes) and some of my theories about how a novel and a short story should be structured in terms of increasing external pressure and mounting personal/emotional stakes.

That led a discussion about books that failed to start just before everything changes but were still popular, most notably Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s/Philosopher’s Stone.

I ultimately said that my answer to writing two divergent storylines coming together was that you needed to do it carefully and to show similar progression in the emotional arcs or the external pressure arcs of the separate characters.

Another student wanted to know how to write a dystopia masquerading as a utopia, which sounded marvelous to me. I brought up Mussolini, and suggested that one way was to show trains running on time. The idea being that if a dystopia has the feeling of clean efficiency it’s easy to mistake it for a utopia. I reminded the student that he needed to be sure to have his p.o.v. character be observant enough to give the reader clues that ‘something’s NOT right,’ even if it’s something like a noticeable military presence coupled with a sense of unease—someone else threw out the idea that a big brother mindset could work. The idea there being that if you show faulty logic as part of the world-building (if you do it in a way that’s not so clumsy people think you’ve made the mistake), you can imply a grim underbelly. I feel, however, we could have done a whole hour and a half class on that question.

I have no idea if my disorganized, jumbled teaching style will work for any of these students, but I have hope. I was impressed by how many of them are actively engaged in writing short stories or novels. In an adult class of the same size, it’s not uncommon to only have half the people actively writing something. In this class, it was 90%. That makes thing easier for me, because often that mean that people have, as shown above, very specific needs that can be met and questions that can be answered.

But, despite all that, I managed to have volunteers for critique. They have to have (no more than, but anything up to) 10 pages of something ready to hand out tomorrow. I got six people ready to go. If even half of them follow-through, that’s a great start.

Published on July 15, 2013 12:05

July 10, 2013

Note for Paul Weimer

I put two posts -- on change and time travel and alternate histories -- on my blog. I'm not going to crosspost them here. You might want to read them, and I'd be interested in your reactions. As a result of that panel (where I talked far too much) I have been doing a lot of thinking about both alternative histories and time travel.

The link to my blog is on the right.

The link to my blog is on the right.

Published on July 10, 2013 09:14

July 6, 2013

An Alternative History Panel

I'm not going back to CONvergence today, since I have an essay to finish. I think it's due today. (I just checked and can't find the last email from the editor, so will have to go on memory.)

I felt I talked too much on the one panel I did yesterday. I was trying to think something through out loud. This should not be done on panels, which ought to be communal activities. Thinking through should be done somewhere private, by oneself or with one or two (very patient) friends.

The ideas I was trying to think through were difficult (for me, at least) and I didn't have a good grasp on them. What is the nature of time? A huge topic, which I am in no way competent to talk about. And what is the nature of history? Does it follow broad trends, like a river that usually keeps to its bed, or is it highly contingent? Can you change it dramatically with a single action?

The final questions I had were, why do people write alternative histories, and why are alternative histories so popular right now?

I have written a couple of alternative history stories in recent years and a number of time travel stories. I think time travel is related to alternative history. Both ask the question, can one change the past? Which becomes the question, can one change the present and future? A hugely important question. We are at a point in history (I think) when the present does not look especially good and the future looks grim. Is major change possible? How do we achieve it?

In any case, I had a lot of questions, too many for a one-hour panel. I'm going back to the con tomorrow. I have one panel, on how to write heroes. I think I will go in unprepared -- with no questions or ideas.

*

Sean Murphy made a very good comment at the panel: change depends on the magnitude of the event. A small event does not change history. A large one does. To use the river metaphor, the course of the Mississippi is not easy to change, but it can be done. The river's course was changed by the New Madrid earthquake. It was a big event. More than that, the Army Corps of Engineers is in a constant struggle with the course of the Mississippi. Their dams and levees are not the same size as the Madrid earthquake, but they are big, and there are a lot of them. Sean was talking about strange attractors, and he lost me. But I think I got the basic point.

History is mostly stable, but it can be changed. It is both a river and a tree of continent events.

*

Having said that, I begin to think about a story involving time engineers, trying to keep history on a certain course, and time saboteurs, planning to blow up levees.

*

Alternative history and time travel stories are, it now occurs to me, a direct challenge to Margaret Thatcher's terrible lie, There Is No Alternative. Both say, history can be changed.

I felt I talked too much on the one panel I did yesterday. I was trying to think something through out loud. This should not be done on panels, which ought to be communal activities. Thinking through should be done somewhere private, by oneself or with one or two (very patient) friends.

The ideas I was trying to think through were difficult (for me, at least) and I didn't have a good grasp on them. What is the nature of time? A huge topic, which I am in no way competent to talk about. And what is the nature of history? Does it follow broad trends, like a river that usually keeps to its bed, or is it highly contingent? Can you change it dramatically with a single action?

The final questions I had were, why do people write alternative histories, and why are alternative histories so popular right now?

I have written a couple of alternative history stories in recent years and a number of time travel stories. I think time travel is related to alternative history. Both ask the question, can one change the past? Which becomes the question, can one change the present and future? A hugely important question. We are at a point in history (I think) when the present does not look especially good and the future looks grim. Is major change possible? How do we achieve it?

In any case, I had a lot of questions, too many for a one-hour panel. I'm going back to the con tomorrow. I have one panel, on how to write heroes. I think I will go in unprepared -- with no questions or ideas.

*

Sean Murphy made a very good comment at the panel: change depends on the magnitude of the event. A small event does not change history. A large one does. To use the river metaphor, the course of the Mississippi is not easy to change, but it can be done. The river's course was changed by the New Madrid earthquake. It was a big event. More than that, the Army Corps of Engineers is in a constant struggle with the course of the Mississippi. Their dams and levees are not the same size as the Madrid earthquake, but they are big, and there are a lot of them. Sean was talking about strange attractors, and he lost me. But I think I got the basic point.

History is mostly stable, but it can be changed. It is both a river and a tree of continent events.

*

Having said that, I begin to think about a story involving time engineers, trying to keep history on a certain course, and time saboteurs, planning to blow up levees.

*

Alternative history and time travel stories are, it now occurs to me, a direct challenge to Margaret Thatcher's terrible lie, There Is No Alternative. Both say, history can be changed.

Published on July 06, 2013 08:34

July 5, 2013

CONvergence

I am off to the 7,000 person monster local SF convention. I have a panel on alternative history at 11 this morning and one on how to write villains at 7 tonight. My final panel is at 11 am on Sunday: how to write heroes.

I actually don't have an opinion on how to write heroes or villains. I write them the way I write all characters: one sentence at a time.

*

I skipped the second panel and came home.

I actually don't have an opinion on how to write heroes or villains. I write them the way I write all characters: one sentence at a time.

*

I skipped the second panel and came home.

Published on July 05, 2013 07:16

Ruins

This is from a facebook discussion of global warming and coastal cities being at risk:

I have a great description in a current story of waves rushing between tall buildings in lower Manhattan... The buildings have been abandoned, except by squatters... One more thing to finish. I have three stories going at once now. Either my writing pace has to pick up, or my imagination has to slow down.I think I have ruined the cities I love best. In Detroit's case, of course, it has more of less happened. The other cities are still with us.

I'm not complaining. This is a lot better than the periods when I feel I have nothing to write.

I'm not sure what the appeal of destroying cities is. I've lived in New York, Detroit and the Twin Cities and put all three into stories as ruins. I've also lived in Honolulu, Paris and outside Philadelphia and not felt any need (as far as I can remember) to reduce them to ruins.

Published on July 05, 2013 07:15

June 30, 2013

New Summer Reading from the Wyrdsmiths

Published on June 30, 2013 09:21

Kelly McCullough's Blog

- Kelly McCullough's profile

- 370 followers

Kelly McCullough isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.