Mike Duran's Blog, page 5

November 15, 2021

Why the “Pandemic Paganism” Boom May Be a Good Thing

The global pandemic has resulted in many unforeseen consequences, some of which we may not fully understand for decades. But perhaps one of the most interesting has been the increased interest in the occult.

Shortly after the 2020 pandemic lockdowns, some noticed that interest in occultism had begun to boom. Social media platforms were seeing a noticeable increase in mentions of “astrology” and esoteric terminology. CNN reported that “psychics and astrologers have seen their customer bases increased exponentially during the pandemic.” In fact, many psychics described 2020 as “a year like no other” saying that “everybody wants to know what’s coming.” Which is one reason why Kemi Mani who runs a spiritual wisdom account on Twitter and increased her following from 50,000 to 300,000 over the course of the pandemic.

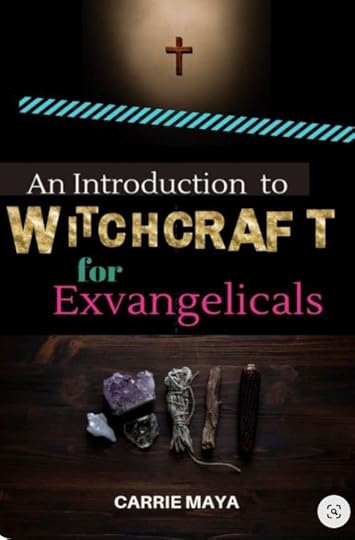

Along with this emerged an exponential growth in witchcraft and Wicca. For example, this writer admits that “The Pandemic Turned Me Into a Witch.” Apparently, she found renewed solace in doing “spellwork” for sick friends and for the speedy development of a vaccine. In fact, during quarantine, many “virtual covens” formed. Like the one developed by Sére Skuld who “proposed to make a hyper-sigil – the union of several magic symbols” to provide her circle of practitioners protection against coronavirus.

Wiccan face mask with pentacle symbol

Wiccan face mask with pentacle symbolThis cauldron of occultism reached its boiling point with the phenomenal growth of #WitchTok during the pandemic. Since TikTok’s inception in 2017, videos labelled #WitchTok have acquired over 18.7 billion views. As a result, celebrity Wiccans and pagans have gathered large online followings. Like Madam Adam, a witch and Tarot card reader who boasts over 1.5 million followers, many acquired during the COVID pandemic, and Kiley Mann, a Jewish folk witch who offers tutorials on creating witch’s wands and talismans for spirit work. #WitchTok has now become a go-to source for pagans to learn about spells of happiness and healing, manifestations, protection potions, and even budget witchcraft candles.

References to and belief in ghosts has also increased during the pandemic.

…mentions of ghosts increased by 83% in March and April (2020) compared to January and February, totalling 108.8k mentions all together. Consumer Research found belief around ghosts seems to be getting stronger. There were 32k people stating they believed in ghosts on social media in March and April, up 39% compared to January and February.

As if that weren’t enough, COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns even led to a spike in calls for exorcisms. As Fr. Gian Matter Roggio, an Italian Catholic priest,

“People have fallen into poverty, they found themselves suffering from anxiety and depression. They feel that their lives are no longer in their own hands but in the hands of a malign force. It’s a big crisis.”

Though this increased interest in the occult may be troubling to some, it is not unusual. This isn’t the first time that people have turned to the supernatural and esotericism during times of global crises and upheaval. For instance, this professor of history notes that

Plague doctor

Plague doctorDuring the previous millennium, the biggest boom in the practice of magic coincided with the Black Death in the mid-14th century.

He labels this “plague magic” and suggests even us moderns still resort to it.

“In times of plague and trauma, we moderns seek to protect ourselves with prayers, charms, sigils and spells as much as any medieval peasant. That a surgical mask is hygienic doesn’t make it any less of a magical symbol.”

Chris French, professor emeritus in the Department of Psychology at Goldsmiths, University of London and head of the Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit, said,

“There’s a lot of evidence to suggest that … all forms of magical thinking tend to increase at times of stress and uncertainty. It has been an incredibly stressful time for so many reasons. You can look at evidence on the sociological level that, in times of great uncertainty, say just preceding the second World War, there was a rise in interest in occult practices. If you look down at the individual level … you find that if you put people into conditions where they don’t feel in control — I think that’s probably the key to this — then again you get this increase in magical thinking, including paranormal beliefs.” (Bold mine)

Feeling out of control and the need to regain some spiritual / emotional equilibrium or self-empowerment appears to be a significant element in the appeal of occultism during the pandemic. For example, this news outlet notes how “uncertainty” has evoked this “new fascination with astrology and the occult.”

The link between spirituality and uncertainty is as old as humanity itself. People look to spiritualism in times of turmoil, said James Alcock, a professor of psychology at York University who studies parapsychological beliefs. That’s why interest in the occult was already increasing before the pandemic, with the chaotic political climate in the US and existential issues like climate change haunting the global consciousness, he said.”This anxiety cries out for some kind of answer about the future, and [the occult] provides an avenue where people can get some kind of answer about the future,” Alcock said.

From the perspective of orthodox historic Christianity, this rise in alternative religions and paganism could be a source of serious concern. After all, it dovetails with another disturbing trend — the rise of the Nones.

This demographic (comprised mostly of dis-affected believers and Millennials and Gen Zers) have abandoned previous religious ties in favor of “none.” But rather than reject all religious affiliations and beliefs, the Nones have simply migrated to alternate forms of religion.

The pandemic may not have initiated a global revival of historic Christianity, but it did reveal that we are an incurably spiritual people.

In her essay “The Rise of Progressive Occultism,” Tara Isabella Burton concludes that “…progressive millennials have appropriated the rhetoric, imagery, and rituals of what was once called the ‘New Age’—from astrology to witchcraft—as both a political and spiritual statement of identity.” Burton writes,

Progressive occultism—the language of witches and demons, of spells and sage, of cleansing and bad energy, of star and signs—has become the de facto religion of millennial progressives: the metaphysical symbol set threaded through the worldly ethos of modern social justice activism. Its rise parallels the rise of the religious ‘nones,’ and with them a model of spiritual and religious practice that’s at once intuitional and atomized. Twenty-three percent of Americans call themselves religiously unaffiliated, a number that spikes to 36 percent among millennials (Trump’s white evangelical base, by contrast, only comprises about 17 percent of Americans). But tellingly, few among this demographic identify as atheists or agnostics. A full 72 percent of “nones” say they believe in God, or at least some kind of nebulously defined Higher Power; 17 percent say they believe in the Judeo-Christian God of the Bible.

While the embrace of witchcraft and New Age thinking among the Nones is indeed troubling, the fact that “few among this demographic identify as atheists or agnostics,” is significant. Or as Burton puts it, “A full 72 percent of ‘nones’ say they believe in God, or at least some kind of nebulously defined Higher Power; 17 percent say they believe in the Judeo-Christian God of the Bible.”

The pandemic may not have initiated a global revival of historic Christianity, but it did reveal that we are an incurably spiritual people.

In fact, much evidence has emerged confirming that people generally become more, not less, religious during times of crises and upheaval. This theologian writes,

during the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers found that online searches for the word “prayer” soared to their highest level ever in over 90 countries. And a 2020 Pew Research study showed that 24% of U.S. adults stated their faith had become stronger during the pandemic, while only 2 percent said it’s been weakened. (Bold mine)

Across the board, the pandemic has strengthened religious faith. As Pew reports,

Nearly three-in-ten Americans (28%) report stronger personal faith because of the pandemic, and the same share think the religious faith of Americans overall has strengthened, according to the survey of 14 economically developed countries.

But while interest in both traditional religion and alternative spirituality have all seen significant upticks during the pandemic, atheism has not. Recent polls reveal that 4% of American adults say they are atheists when asked about their religious identity. But apparently, believing in no God and no afterlife is not a compelling proposition during a global pandemic. There is no evidence that atheism significantly increases during times of societal crises. On the contrary, it is less developed countries which tend to be the most religious (causing some to conclude that peace and prosperity, rather than crisis, is more conducive to the growth of atheism).

Because atheists place their hope in Man and Science, the pandemic has become a context for demonstrating their humanistic “faith.”

We trust secular humanism, the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and the solving of human problems, to get us through times of trouble. Secular humanists have no choice but to rely on and trust each other. We trust that the innate goodness and helping hands of our fellow man will be there in this time of crisis. This gives us comfort and hope.

We have trust that solutions to COVID-19, both in the form of treatments and vaccines, will come from scientists and other professionals. This trust is based on evidence and history.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that the demographic with the most uniform, monolithic response to COVID-19 has been atheists. In fact, atheists are more likely to get vaccinated than any other single demographic.

While many have taken Christians to task for vaccine hesitancy, pagans appear equally divided on treatment. Like this popular TikTok witch who scolds the vaccine hesitant among her ranks.

Of course, claiming to be part of an “activist” movement while pledging allegiance to Science and Government seems ironic. Nevertheless, other devotees do not embrace such a hard-line stance.

For example, Alex Brady asks Can You Treat Coronavirus With Magic? Depends Which Spiritualist You Ask. He notes,

Famous Instagram witches like Bri Luna (@yungkundalini), who boasts over 30,000 followers, post witchy photos with a COVID-19 bent. (On March 22 she posted a picture of herself standing over the sink in a sweater and underwear, with the caption “Wash your hands.”) Others, like witch and tarot reader Emma Westbrook, whose Zoom tarot class I’ve been taking, offer sound baths for healing on Instagram Live on @weaving.witch. Famous astrologers like Rebecca Gordon—founder of the Rebecca Gordon Astrology school—offer free virtual webinars like one in mid-April called “Social Distancing Through the Zodiac.”

While the science behind “Social Distancing Through the Zodiac” is unclear, the message behind “Wash your hands” is not.

The result is an amalgam of pagan approaches to the pandemic. So while these pagan health care providers are pledged to science, these Wiccans have joined with local anti-vaccine activists in hopes “to prevent childhood vaccinations and treat Autism with Witchcraft.” This priestess for the Temple of Hecate calls upon “the great Guardians of the East, South, West, and North” asking them to “‘wipe out this virus, burn it away, and eradicate it from this Earth!,'” while also believing that “we need to wear a mask and gloves to honor the society we live in” and that “witches… do believe that their magic can cure people of the virus.”

In fact, in doing research for this article I was connected with a Wiccan practitioner who fielded questions. She absolutely disavowed vaccination under any circumstances, saying “it is a chemical being injected into what I consider my sacred being which belongs to no one but me. It was gifted to me by the Lord/Lady for my time here on earth, it is not owned by the Govt, the medical or scientific communities, and that is not up for discussion.” In fact, having had COVID, she outlined a detailed list of herbal and alchemical treatments, concluding that “every person has his/her own relationship with his/her God and that shall not be infringed.”

While many have taken Christians to task for vaccine hesitancy, pagans appear equally divided on treatment.

So while paganism has increased during the pandemic, a singularity of approach to the virus has not. This could have to do with the de-centralized, individualistic nature of many alternative religions. There is rarely a formal institutional structure that unites all practitioners. So while there is a Satanic Bible and a Church of Satan, there is no Pagan equivalent.

Interestingly, whereas traditional occultists and esotericists operated on the fringes of Government, science, and medicine, todays occultists seem more beholden to them. Whether this support of the Government, acquiescence to Science and traditional medicine, indicates a shift in contemporary paganism is unclear.

Either way, the pandemic has clearly revealed one thing — Atheism is not the default for human beings. It will always be an outlier. In times of crisis or instability, people do not turn to nothing. (Of course, one could argue that atheism simply swaps a Supreme Being for Science and Man.) While the increase of interest in the occult signals the waning of traditional religion and the prevalence of alternative worldviews, it is nevertheless a reminder that humans are spiritual beings wedded deeply with Nature and invisible forces that imbue it. Yes, turning to Nature, goddesses, and magical amulets is misguided and can lead to great spiritual deception. Nevertheless, acknowledging forces beyond ourselves, something supernatural, Someone more wise and powerful than us, is intrinsically human.

So while the pandemic may not have initiated a global revival of historic Christianity, it did reveal that we are an incurably spiritual people.

October 27, 2021

“Woke Horror” — The New Monster on the Block

The horror genre has long been a vehicle for social and moral commentary. The Atomic Age spawned many cautionary tales about the potential dangers of nuclear weapons, whether they be mutational anomalies or apocalyptic futures. It’s widely accepted that Jack Finney’s 1954 novel The Body Snatchers and its 1956 film adaptation are direct allegories to the 50’s Moral Panic and McCarthyism. Cautionary horror like The Fly evoked dangers of tinkering with Mother Nature. And John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) is a blatant critique of advertising, media, consumer culture, and mass mind control.

But while some directors have openly affirmed socio-political sub-texts to their films, postmodern deconstruction has often led to over-reach and nonsensical interpretative stretches. For example, Frankenstein is sometimes viewed through the lens of queer theory and transexuality, with the Monster representing “aspects of body dysmorphia.” Some describe The Exorcist as a commentary on xenophobia, enacting “the paranoia of a Western male-dominated society resisting changes that increasingly include the voices of those previously unheard: women, young people and members of our larger global world.” Others note that the alien Spores of The Body Snatchers can be viewed in the context of “queer themes” (the pod people are “the other,” they cannot biologically procreate but can still replicate.) The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was viewed as a metaphor for Nixon-era mayhem as well as Hicksploitation. While other critics interpreted David Cronenberg’s body horror movie The Fly (1986) to be about the AIDS crisis. And Bram Stoker’s Dracula has been charged with everything from misogyny, to racism, to homophobia, as well as “ecophobia” or “fear of the unknown in nature” (via “gothic ecocriticism”).

In the 21st century, this interpretive overreach has witnessed a sharp Left turn.

Perhaps one of the best evidences of this is personified by the word “woke.” Not only have standard dictionaries added the word to their catalog, entire industries and genres are now designated by it — woke films, woke fiction, woke comics, woke churches, woke music, woke brands, etc., etc. Dictionary.com defines “woke” as “having or marked by an active awareness of systemic injustices and prejudices, especially those related to civil and human rights. “To be “woke” is to be (and remain) vigilantly aware of systemic biases, power inequity, and obstacles facing marginalized communities. Identitarianism plays an integral part in woke dogma, as individuals are often parsed by ethnicity, gender, class, and sexual preference. Today’s woke culture has combined postmodern academic aesthetics with countercultural militancy, sifting all cultural commodities through the sieve of intersectional theory, identity politics, antiracism, and diversity.

The horror genre is just one of many pop cultural commodities now being scrutinized and co-opted by a new breed of social justice activist. As such, an emerging category of “woke horror” has sloughed into the light. Lists of “woke horror” films are now appearing, as well as the filmmakers who make them. For example, IMBd has compiled 47 “Woke Horror” films. There’s also a list of filmmakers leading the rise of woke horror. Ranker has grouped The Most Woke Movies of All Time, with quite a few horror films included in the mix.

The horror genre is just one of many pop cultural commodities now being scrutinized and co-opted by a new breed of social justice activist.

So what distinguishes “woke horror” from, um, normal horror? Basically, overt social justice messaging. “Woke horror” addresses “systemic injustices and prejudices.” Racism, white privilege, and white supremacy are thematic constants, as is sexism, feminism, toxic masculinity, and the Patriarchy. Revenge (often feminist revenge) is a common trope in “woke horror,” typically juxtaposed against some power imbalance (personified via bullies, jocks, abusive husbands, or corporate execs). Diversity is also a huge element of “woke horror,” casting people of color, bi-racial couples, and LGBTQ representatives in rather predicatable order. (This has even spawned sub-genres of Gay Horror and Queer Horror.) Inclusion of marginalized groups is common, especially migrants and religious / ideological minorities (such as pagans, witches, and occultists). And with climate change now viewed as a social justice issue (see: climate justice), capitalism and the environment are also addressed, with Anarchy and Nature exerting appropriate revenge.

Addressing such contemporary issues and themes should be well within the purview of art. However, the problem with “woke horror” is that social justice messaging is subsuming good storytelling and its proponents are “cancelling” art and artists that do not share their political sympathies.

For example, the film most often ranked as a prime example of “woke horror” is Jordan Peele’s Get Out. Some have described it as The Little Movie With A Big Message. What is that “big message”? Well, a writer at Vox suggests that the film “deconstructs racism for white people.”

Get Out ingeniously uses common horror tropes to reveal truths about how pernicious racism is in the world. It doesn’t walk back any of its condemnations by inserting a “white savior” or making overtures to pacifism and tolerance. No: In this film, white society is a conscious purveyor of evil, and [the protag] must remain alert to its benevolent racism. He has to in order to survive.

In keeping with postmodern literary deconstruction, the author distills the film’s message into essential antiracist bullet points:

Get Out frames violent black resistance as a necessity born of desperationWhite feminism is portrayed as a bluffWhite microaggressions are framed as masking real dehumanizationCode switching is portrayed as a tool to make white people more comfortableA pretty lofty achievement for a horror film, huh?

Of course, others saw the film as a heavy-handed, race-baiting, tract. Like this reviewer at IMBd:

Peele does a great disservice to true victims of racism by reducing the tormentors to a group of straw men and women who are easily set aside. In real life, of course, racism is a far more complicated affair and sometimes the victims turn out to be as bad as their oppressors.

Get Out marks a new low in race relations with Peele setting a poor example for impressionable youth. Instead of trying to mend fences, Peele is content to present African-Americans as perennial victims at the hands of stereotyped white tormentors. No race or ethnic group has a monopoly on benevolence despite Peele’s lame and misguided outlook to the contrary.

Nevertheless, the film was almost-universally hailed as one of best movies of the year.

Similarly, Guillermo de Toro’s The Shape of Water, a weird horror / urban fantasy period piece was awarded Best Picture of Year. Despite the accolades, the film’s social justice messaging prompted critiques of its heavy-handed approach. The film checks off all the appropriate “woke” identity boxes:

Handicapped (mute) female lead characterBlack female protagonistLonely gay manImprisoned, tortured, sympathetic human-like “monster” Repressed, white, racist, Christian, male as villainThe film is at once a stunning achievement in production design and an indentitarian’s wet dream. As one author points out in The problem with ‘The Shape of Water’ and other ‘woke’ films is that the movie’s messaging is about as subtle as a sledgehammer to the solar plexus.

The problem with the trend of woke cinema is the way in which they so proudly broadcast their very wokeness. Once-disreputable genres are scrubbed of their shagginess, subtlety and nuance, and injected with the thematic pretension and bloat that sinks the worst “serious dramas.” Irrespective of their ostensible merits, or demerits, films like Get Out, the cross-cultural romance The Big Sick and The Shape of Water seem to exist in part simply to be liked. Conspicuously enjoying them, and announcing that enjoyment, expressed not only a given viewer’s taste, but their whole worldview.

Many “woke horror” entries now exist simply to “broadcast” one’s social justice bonafides.

One writer at The Grimoire of Horror, in his review of “Wrong Turn” (2021), openly pines for the the End of Woke Horror. Why? Because any semblance of story in the film has been swapped for formulaic social justice messaging. For example, he describes the characters as ” little more than a checklist of political correctness.”

Darius (Adain Bradley) is an African American whose work in the nonprofit sector he hopes to translate into a better world where people follow through on Dr. Martin Luther King’s dream. His white girlfriend (Charlotte Vega) has two doctorates. His friends Adam (Dylan McTee) and Milla (Emma Dumont) are an app developer and an oncologist, respectively, and there’s a gay, biracial couple in tow.

Conveniently, the convoluted backstory traces the hillbilly mutants to, you guessed it, white Southern Confederates.

Jamie Lee Curtis was not shy about attaching the most recent Halloween entries with the #MeToo movement. In summing up the final entry into the series’ film canon, she frames it as feminist revenge porn. Curtis says, “any woman who fights back is a survivor and a champion, and we have a world right now where women are finally saying enough is enough, time’s up, #MeToo.” In fact, the #MeToo movement has prompted a wave of female revenge flicks, providing ideal inclusion into the “woke horror” brand. Like the latest iteration of The Invisible Man. Writers at Vogue magazine declared that With The Invisible Man, Horror Is Starting to Get #MeToo Right. Over at Slate, one author surmises that the #MeToo era of film is producing Monster Girls. “Monster girls flip the script on social anxiety and show us girls that can walk confidently through the world, unafraid of empty night streets or slow-driving cars.” Apparently, it was “the era of Trump” that spawned these bad-ass Monster Girls. This idea of girls “flipping the script” led to what one writer called #MeToo’s first horror film, 2018’s Revenge. The film is described as an exploitation movie for the #MeToo era. Ironically, “exploitation” is the exact thing #MeToo aims to correct.

#MeToo and the female empowerment narrative dovetail with another horror trope — witchcraft.

The Craft: Legacy, sequel to the 1996 teen horror, is described as centering “woke witchcraft” while “highlighting the importance of embracing intersectional female power while being aware of the dangers of toxic masculinity.” Of course, witchcraft has often been used as a vehicle to represent female awakening or empowerment, whether sexual, social, or political. But in The Craft: Legacy, magic is simply a tool for social justice. In this case, it is to upend oppression. Perhaps the most effective of all the spells in the film is one which transforms a knuckle-dragging bully onto “an ultra-woke defender of social justice,” from a “mean jock” to a “vulnerable empath.” What better revenge than using feminist “magic” to convert the un-woke into Social Justice Warriors?

As columnist Ross Douthat put it, “witches are the new woke heroines.” He quotes from a recent New York Times story promoting the reboot of the TV witch drama Charmed, claimed that the witches of Charmed are “out to slay demons. And the Patriarchy.” Netflix’s Chilling Adventures of Sabrina is notably more serious about its occult content than the earlier series upon which it was based. The actress who plays Sabrina admits “She’s a woke witch.” In Sabrina the Teenage Witch’s New Power Is Being a Woke Feminist the writer at Jezebel explains,

the show is actively trying to be more progressive and inclusive of different gender identities and sexualities. (Sabrina’s cousin, played by Chance Perdomo, was billed as pansexual at the time of casting.) Shipka’s co-star Lachlan Watson also referred to the show’s intersectional feminism, as demonstrated by their character Susie, who is non-binary…

Indeed, LGBTQ representation is another major plank of Woke Horror. For instance, Rotten Tomatoes aggregates 30 Essential LGBTQ+ Horror Movies. Why exactly The Haunting (1963), Let the Right One In (2008), and Hellraiser (1987) are included is not entirely clear. Likewise, the folks at Out magazine compile a list of 13 Queer Horror Films & Shows to Stream This Halloween Season. Apparently, they consider the Halloween holiday as the “official Gay Christmas.” They note such films as Jennifer’s Body, which is described this way: “[Megan] Fox plays a teen girl who gets possessed by a demon, makes out with her female best friend, and starts killing boys.” And then there’s the new Chucky series on SyFy. Apparently, Chucky Is Back & Queerer Than Ever Thanks to His Gay Creator, the main character being “a queer teen boy named Jake. “

Social commentary and contemporary themes should be fair game for creatives. Furthermore, pursuing ethnic and gender diversity in film and fiction can be noble pursuits. The problem is when ideologies and ideologues subvert free expression and co-opt artistic mediums for purposes of indoctrination, virtue signaling, and political messaging.

This author notes how The Purge franchise has been hijacked by such ideologues. In Let ‘woke’ horror movies die: ‘The Forever Purge’ begs for liberal praise by devolving into anti-Trump fanfiction for CNN viewers, he writes

The ‘Purge’ franchise began as an interesting examination of morals, but it has quickly turned into the latest example of wokeism destroying art and turning creators into part-time, ill-informed political pundits.

Sadly, many fans and critics have become gatekeepers of this emerging political correctness.

For example, one critic slammed A Quiet Place as “socially regressive.” Why? Because

“its central narrative [was] about a white family with guns protecting their home from ‘a bunch of big, dark, stealthy, predatory creatures.'”

Because everyone knows that white families with guns protecting themselves from monsters can only imply one thing — racism.

The “woke horror” aficionado sees everything through the lens of race and identitarianism.

Like, this pastor who sees the iconic celluloid serial killers from Halloween and Friday the 13th as analogous of the Patriarchy, their weapons just “phallic” symbols.

“A socially stunted man wields a phallic weapon to kill the teens who are into sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll… The Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees of cinema, demented though they may be, uphold patriarchal values.”

The “woke horror” aficionado sees everything through the lens of race and identitarianism.

Another woke critic finds racist overtones in the final scene from John Carpenter’s The Thing:

as the camera frames the survivors in medium close reverse shots of mutual suspicion, one can discern that the breath of the white man is heavily fogged in the Antarctic air, whereas the black man’s is not. The implication is subtle but clear. The Thing lives on and, interestingly enough, its carrier is yet another socially marginalized form, the black male.

But such overreach and interpretive abstraction appears common to the woke critic.

More recently, critics of the latest Ghostbusters incarnation, Afterlife, take it to task for ignoring the all-female reboot. One of the female stars of the 2016 box office failure sees Afterlife’s rebuff as an extension of the misogyny and racism that the film allegedly evoked. Of course, it couldn’t have been that the all-female remake was a poorly executed, feminist-messaging, bore.

But when one sees everything through the lens of racism and misogyny, racism and misogyny will be found everywhere.

The horror genre has always provided social critique and commentary. This won’t and shouldn’t stop. However, a new type of militancy has now tainted our dialog, polarizing parties and subsuming our art. Sure, this “threat” can be exaggerated. But if the horror genre is any indication, the “woke monster” is a very real danger. Not only does this ideology threaten to hijack our art for the purpose of social justice propaganda, but it turns us into nit-pickers and auditors, pitting fans and creatives against one another in a fascistic deathmatch. But just like any good horror protagonist, facing the monster is unavoidable.

October 2, 2021

Netflix’s “Midnight Mass” Offers Salvation without Bite

This review contains major spoilers.

***

As a young preacher, I learned early on that the “The mind cannot retain what the seat cannot endure.” Even the best of sermons miss their mark when too long-winded. Make no mistake about it, director Mike Flanagan’s latest entry in the horror genre, “Midnight Mass,” is both a “sermon” and “long-winded.” However, the punch line to this cinematic polemic is more about gauzy postmodern logic than anything with theological bite.

Some have described the new Netflix miniseries as “Catholic horror at its best.” Although the story is centered around St. Patrick’s Church, a small Catholic church on sparsely populated Crockett Island, the inclusion of a variety of religious representatives is evidence enough of the director’s intended story arc and ensuing religious cerebrations. There’s a practicing Muslim, a staunch atheist, and a doctor (repping #Science, of course). All provide significant pushback to the largely naïve, when not blatantly malevolent, Catholic parishioners.

The arrival of Father Paul (played by Hamish Linklater) sets the story in motion. Linklater gives an especially compelling performance as a charismatic, but darkly duplicitous figure. Running cover for Father Paul is Bev Keane, an incarnation of Mrs. Carmody if ever there was one. Carmody, if you remember, was the rabid religious fundamentalist of Stephen King’s “The Mist.” Such caricatures are common in film and Bev Keane fills the role admirably, protecting Father Paul’s sinister ministrations, framing Muslims as terrorists, and quoting Bible verses to suit her apocalyptic paranoia. But when miracles follow the priest’s arrival (healings and recoveries), the entire town is prompted to give heed to he (and Keane’s) zealotry.

The revelation of the source of these miracles (Episode 3-4) will likely be the watershed for viewers’ opinions about “Midnight Mass.” The “big reveal” is not that God, Father Paul, or Bev Keane are actually behind this “revival.” You see, the good priest was previously a senile, dementia-addled cleric who encountered a gaunt, leathery, blood-sucking angel in the Holy Land. (More on the actual nature of said “angel” in a minute.) Now, Father Paul, revitalized from drinking the wraith’s blood, has brought the winged creature back to Crocket Island in hopes of baptizing a flock of revenants like himself and creating an “army of the Lord.” As such, Saint Patrick’s becomes the vehicle to spread this new “gospel,” while the defiled Eucharist, spiked now with the blood of the “infected,” is the actual contagion.

But as troublesome as the imagery of the profaned sacraments are, its the series’ religious implications that I found most problematic.

Flanagan has been up front about his unsettled Catholic upbringing and subsequent religious quest. His philosophical conclusions permeate “Midnight Mass.” In this essay, the director describes his religious search and the ideas that have most influenced him:

I read the Bible. And then I kept reading. If I was going to look for God, I was going to look everywhere. I devoted myself to studying Judaism. Hinduism. Islam. I connected pretty intensely with Buddhism for a few years in there, even seeking out temples in Los Angeles as I tried to further explore it, but ultimately the book that impacted me the most was God is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens. That led to Letter to a Christian Nation by Sam Harris. But I found more spiritual resonance reading Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan than I found in two decades of Bible study.

Hitchens, Harris, and Sagan represent the holy trinity of the New Atheists. Their perspectives, all particularly hostile to historic Christianity, led Flanagan to a new conclusion on religion:

My feelings about religion were very complicated. I was fascinated, but angry. Looking at various religions, I was moved and amazed by their propensity for forgiveness and faith, but horrified by their exclusionism, tribalism, and tendency toward fanaticism and fundamentalism. I found a lot of these various religions’ ideas to be inspiring and beautiful, but I also found their corruptions to be grotesque and unforgivable. I wasn’t going to support those kinds of institutions any longer. I was only interested in humanism, rationalism, science… and empathy.

This disconnect between the “inspiring and beautiful” elements of religion and its “tendency toward fanaticism and fundamentalism” is the thematic heart of “Midnight Mass.” To his credit, not all the religious portrayals in the series are that of crazed, merciless fanatics. Many of the congregants of St. Patrick’s are seen as good people simply being led astray by corrupt shepherds. Yet many reviewers recognize that “Midnight Mass can be read as a pretty sharp commentary on organized religion, Christianity in particular.” Both the “dark angel” and the “thirst” it imparts are fictional springboards to embody the perverse machinations of religious charlatans. The profaning of Scripture and religious iconography are just casualties along the way. But make no mistake, that profaning is a horror all its own.

It’s why this writer described the series as using horror “to explore the dark role religion can play in the lives of working-class people. Viewers will be taken on a journey involving both sinister and benevolent forces, which may have them reflecting on the complex role faith and dogma has played in the history of humankind—for better and worse.” And this reviewer at Roger Ebert.com correctly notes that “Midnight Mass” mines “the idea that The Bible truly is a horror story.” While I’m sympathetic to the idea of “Bible as horror story” or “the complex role faith and dogma has played in the history of humankind,” I wonder that Flanagan has erected little more than a straw man to plunder.

Unsurprisingly, it’s the “non-Christian” characters in “Midnight Mass” who are some of the most spiritually lucid. Both the atheist and the Muslim have lengthy monologues about religion, philosophy, human suffering, addiction, xenophobia, and the afterlife. In fact, nearly the entire half of one episode is simply a discussion, in a single room, between Father Paul and Riley, a recovering alcoholic and atheist. Drawn-out soliloquys are par for the course in this series. While it definitely gives characters an opportunity for depth, it also infers their role as spokespersons for a much larger existential exploration. Which Flanagan himself corroborates.

Religion, I believe, is one of the ways we attempt to answer the two Great Questions that ache within us all: “how shall we live,” and “what happens when we die.” I don’t know the answer to the second question (although my thoughts, wishes, and even my best guess are articulated in this show), but Midnight Mass has, over the years, helped me at least begin to answer that first question.

But articulating those “Two Great Questions” is clearly not the only thing the director aims to accomplish. His sympathetic portrayals of both atheists and Muslims have garnered praise… from atheists and Muslims. One reviewer even notes how the Muslim character, Sherriff Hassan, “is one of the few people [in the series] who is lifted as model for how religious devotion can be positive… Respect, humility, kindness in the face of hatred, and helping the needy are some of the biggest lessons that appear in religious texts time and time again. These often-preached tenets of Christianity are displayed through a Muslim man.” Religious News Service writer Jillian Chaney sees the series as directly addressing evangelical fears of “Islamophobia.” She writes,

“To watch Crockett Island’s residents fear Hassan more than they do the monsters at their doorstep is a twisted irony that makes the show a dark delight. “

Such a portrayal does not seem coincidental. While Flanagan appears intent to level “a pretty sharp commentary on organized religion, Christianity in particular,” atheism and Islam get a pass. And nonsensical pantheistic orations are offered uncritically. Like that of Erin (one of the shows’ unlikely heroines) who, as the end draws near, offers this final soliloquy about what happens at death:

“… every atom in my body was forged in a star. This matter, this body is mostly just empty space. After all, solid matter is just energy vibrating very slowly, and there is no me. There never was. The electrons of my body mingle and dance with the electrons of the ground below me and the air. I’m no longer breathing. And I remember, there is no point to where any of that ends and I begin. I remember that I am energy, not memory. My name, my personality my choices all came after me. I was before them and I will be after. Everything else is pictures picked up along the way. Fleeting little dreamlets imprinted upon the tissue of my dying brain. And I am the lightning that jumps between, the energy firing neurons. And I am returning. Just by remembering I am returning home. It’s like a drop of water falling back into the ocean. Of which I’ve always been a part. All of us, a part. You, me, my mother and my father, every one who’s ever been. Every plant, every animal, every atom. Every star. Every galaxy. All of it. We’re galaxies in the universe, grains of sand on the beach. And that’s what we’re talking about when we say God…. We are that cosmos that dreams of itself. It’s a simple dream that I think is my life every time… It’s all one. I am everything. I am the ground beneath me. I am my little girl. I am my mother. I am Father Paul and this miracle. We are all of the same thing.”

Erin finally concludes with the phrase, “I am that I am.” Those familiar with Scripture will recognize this as a phrase used by Christ about Himself and Yahweh, a term exclusive to Deity. The fact that Erin uses this Scripture to describe her Infinite Self is indicative of Flanagan’s reckless application of Scripture and the postmodern mashup of beliefs that form the scaffold of this rickety worldview.

It also reveals what are the real “monsters at their doorstep.”

“Midnight Mass” does not use the word “vampire” to describe the bat-winged, blood-thirsty, “angel” unleashed upon the inhabitants. Nevertheless, Thrillist summarizes thusly: “Father Paul is a vampire, and Midnight Mass is a vampire story.” However, the ambiguity surrounding the creature has left some asking “Is Midnight Mass’ Monster An Angel Or Vampire?” In this interview, Flanagan explained, “Whenever God needs to do something horrible to someone in the Bible, he sends an angel. Do you really want to meet a creature like this? Imagine what that creature must be like.” Furthermore, when Father Paul first encounters the being, and his aging self is revitalized by the creature’s blood, he describes it as an “angel of God” sent to save him. Nevertheless, the fact that a Catholic priest cannot discern a vampire from an angel says much about the theological acumen of the characters, and their creator. In What the Bible Says About Midnight Mass’ Angel, Mikey Walsh correctly notes the blatant deception and selfishness behind Father Paul’s decision to bring the beast back to Crockett Island. But by the time he realizes his folly, all is lost.

And that’s the real “monster” at the church’s doorstep. It isn’t a revenant, a vampire — it’s Man. It’s Bev Keane spouting Bible verses while torching the city. It’s Father Paul, defiling the sacraments for power. It’s the church that brainwashed the entire flock. It’s religious fundamentalism.

But salvation is extended to all. For as the sun rises upon the island, the infected inhabitants march forward singing “Nearer My God to Thee” while turning to ash in the glorious Light. They are now one with the Cosmos, returning to pure energy; all their memories but “Fleeting little dreamlets imprinted upon the tissue of [a] dying brain.”

Flanagan summarizes his “Greatest Commandment” this way:

“For most of this project, there was a preoccupation that I had with what happens after we die. What is the correct answer? How do we answer that question in life?” he explains. “I think it took me until very recently, until the last real swing at this [script] to realize that doesn’t matter, so much as the question about what we do when we’re alive. To the degree with which what you might believe or what I might believe happens after we die. The only thing that matters is how that belief changes our behavior toward each other while we’re alive.” (Bold mine)

In the end, be good to each other. Whether atheist or Muslim or Catholic, whether vampire or human, “The only thing that matters is… our behavior toward each other while we’re alive.”

In this, the salvation director Mike Flanagan offers is toothless. It doesn’t matter what your religious or anti-religious persuasion is, just be a good person and you too will evaporate into the Great Cosmic Void. Unlike Jesus, Who made sharp religious claims and warned of consequences for those who did not believe, the message of “Midnight Mass” is simply, “Don’t be a monster.”

But in that world, the only real “monsters” are of the fundamentalist kind.

Nevertheless, take heart — no matter what you choose to believe, we’re all just stardust, “like a drop of water falling back into the ocean. Of which [we’ve] always been a part.” The Vast Cold Cosmos awaits! And that, my friends, is the real horror.

September 21, 2021

Guillermo del Toro and the Postmodern Fairy Tale

Apologist Frank Turek’s book, Stealing from God: Why Atheists Need God to Make Their Case, expounds upon the premise that atheists must borrow from theists in order to make their points. For example, in order to argue that the existence of suffering and evil proves there is no God, one must appeal to an Absolute Good. We know what is Evil because we intuitively know what is Good. But if there is an Absolute Good that transcends the material world, where did it come from? In other words, atheists must appeal to a transcendent metaphysic in order to make moral arguments against God.

A similar dynamic is at work with secular creatives. Many contemporary artists and mythmakers are atheists or agnostics. Nevertheless, they appeal to transcendent spiritual concepts or gauzy metaphysical absolutism upon which to ground their mythologies.

For example, Stanley Kubrik was described at various times as either atheist or agnostic. He is included in a list of Famous Atheists by Atheist Alliance International. However, he also described the film 2001 as providing a glimpse into his “metaphysical interests.” Said the director, “I’d be very surprised if the universe wasn’t full of an intelligence of an order that to us would seem God-like. I find it very exciting to have a semi-logical belief that there’s a great deal to the universe we don’t understand, and that there is an intelligence of an incredible magnitude outside the Earth. It’s something I’ve become more and more interested in.” Indeed, the capstone of 2001 is a mind-bending psychedelic transformation of the protag into a divine-like Star Child. Of course, the “God-like” intelligences Kubrik hypothesizes could simply be an extension of the “sufficiently advanced technology” Arthur C. Clarke postulated. In either case, in Kubrik’s squishy atheistic outlook, an “intelligence of an incredible magnitude [may exist] outside the Earth.”

James Cameron is an avowed atheist who even went so far as to call agnosticism “cowardly.” Nevertheless, Cameron’s epic 3D film Avatar creates a vast mythology all its own. The story centers around the Na’Vi, indigenous aliens who save themselves and the movie’s hero through their faith in Eywa, the “All Mother,” a pantheistic deity which is described variously as a network of energy and the sum total of every living thing. While “All Mother” “does not take sides” but only balances nature, she appears to co-opt Western morality as She sees convenient. As I wrote in Avatar’s Fickle Deity, “all the while Avatar is pushing a New Age, Neutral Deity, that Deity is busy acting very non-New Age and un-Neutral, arming her forces to the teeth. In the end, the Impartial, Impersonal Force of Cameron’s world turns partial and personal, comes to the rescue and turns, tooth and claw, on the bad guys.”

Atheist artists, though disbelieving in a spiritual dimension, often evoke the fantastical in their work, something outside of the material world.

Similar incongruities can be found in atheist creatives like Joss Whedon, Doug Adams, Neil Gaiman, Phillip Pullman, or Isaac Asimov. Atheist artists, though disbelieving in a spiritual dimension, often evoke the fantastical in their work, something outside of the material world, whether love, morals, metaphysics, non-material intelligences, or invisible terrors. Although they disavow a Creator and embrace a world without meaning, they still imbue their own creations with wonder, magic, hope, and purpose.

Film director Guillermo del Toro may be at the top of this list of artists.

An exposé in The New Yorker entitled Show the Monster, builds upon biographical tidbits from the director’s Catholic upbringing and their devastating impact, describing del Toro now as a “raging atheist.” He is listed in the IMBD database of Atheist Film Directors. At The Hollowverse, a site that aims to highlight “The religions and political views of the influentials,” de Toro is described as being “somewhere between an atheist and an agnostic…”

Despite this, del Toro’s films are packed with images of the fantastical and otherworldly — angels, demons, religious symbology, and the perennial battle of Good and Evil.

In his interview at NPR, the apparent discrepancy of “his interest, as an atheist, in spirituality” is noted. Del Toro responds:

“I have a lot of spiritual curiosity and beliefs… I believe there is a spiritual dimension, without a doubt, to both our world and our existence in it. What I don’t like is organized religion… A lot of us are born with a clear feeling of what is right and what is wrong, and ultimately are governed by that, and I think there is a spiritual dimension to this.”

So is it possible to be a true atheist and still believe that “there is a spiritual dimension” to life? Perhaps this is why some interviewers characterize del Toro as “a divided soul.”

In his feature on de Toro, Guardian writer Mark Kermode describes the director this way,

In essence, del Toro is a divided soul, a realist attuned to the strange vibrations of the supernatural, a lapsed Catholic (‘not quite the same thing as an atheist’) with an interest in sacrifice and redemption who turned down the chance to direct The Chronicles of Narnia because he ‘wasn’t interested in the lion resurrecting’.

Indeed, the influence of Catholicism upon the director, and his current aversion to “organized religion” — and apparently the Resurrection of Christ — reveals much about del Toro’s cinematic vision.

Shaped by the traditional Catholic religion in Mexico, extreme notions of sin, guilt, and penance were driven home upon the young man. The Hollywood Reporter describes one incident:

…Josefina [his grandmother] placed jagged metal bottle caps inside his shoes, “upside down, so that I would bleed to mortify the flesh to pay for purgatory,” [del Toro] remembers. “My mother discovered them and said, ‘Don’t do that again.’ But there were many bottle caps, metaphorically, that were put in there. I formed a bond with her that was full of guilt, because she explained to me things like original sin, and that was really difficult for me to understand. The notion of sin, the notion of damnation — there is a lot of pain in the Catholic religion in Mexico; there is a lot of guilt.”

But this religious influence took on even darker turns when his grandmother attempted to exorcize the boy. “She exorcised me a couple of times,” he said. “Threw holy water at me.”

Could this explain both the director’s disavowal of religion and the proliferation of religious themes in his works?

In his interview with NPR, del Toro describes his vampire trilogy, The Strain, as containing “a lot of ruminations that are almost of a spiritual nature” which occurs in “a world where you come to realize that we all are pawns of a battle between good and evil, that our actions can be measured in spiritual terms.”

Hell

HellBy: Francesco Francavilla

In her article, Patron Saints Of Imperfection: On Guillermo Del Toro’s Love Of Monsters, Priscilla Page expounds upon the religious themes in del Toro’s cinematic replication of Mike Mignola’s popular graphic novel.

Hellboy opens on an image of Christ on the cross at the scene of Hellboy’s birth. Hellboy carries his adoptive father Professor Broom’s rosary, and at the film’s climax, his handler Agent Myers uses the rosary to remind him who he is: even though he’s destined to usher in the apocalypse, Hellboy can resist his fate, and he chooses to do the right thing by not ending the world.

In the scene described above, Hellboy stares at the image of the cross burned into his palm and reawakens to his calling, snapping off his newly grown demon horns before saving his friends and father’s legacy.

So while del Toro is critical of organized religion and traditional theistic forms of belief, he still tells cinematic narratives that are spiritual in nature, filled with myth and magic. Which is why many see his work as compatible with a Christian worldview.

For example, actor Doug Jones, who’s played numerous characters in del Toro films (like Abe Sapien in Hellboy I and II, the Faun and the Pale Man in Pan’s Labyrinth), wrote the Forward to The Supernatural Cinema of Guillermo del Toro, a series of academic essays on the director’s work. Jones, a Christian, confesses that when asked to consider a role in Hellboy, a film about a repentant demon from hell, he initially thought he would have to decline the film because it would offend his “Christian sensibilities.” Instead, Jones discovered that the storyline contained numerous redemptive references and imagery that bolstered a biblical view of the world.

However, despite del Toro’s affinity for religious themes and belief that “we all are pawns of a battle between good and evil,” there are tremendous inconsistencies and contradictions in the director’s worldview. For instance, in his interview at Big Think entitled Guillermo del Toro’s Personal Religion, the director boiled his philosophy of life down into a rather simplistic, if not obscure, moral obligation:

“You just need to try to be a good man. To a certain degree. You know? As good a man as you can be. Whatever that measure is, be it you’re a serial killer, a war hero, or a Samaritan, whatever you are, be as good a man as you can be.”

In del Toro’s universe, being good, whether a “serial killer” or a normal guy, is the sole path to redemption, the crux of a life well-lived. Of course, such a conclusion is ultimately ambiguous. Especially as a professed atheist. What does it mean to be a “good person”? Who sets the standard of “Good”? Are the standards of Goodness different for everyone? And what does being good redeem us from, or to? In an atheistic universe, there is no heaven or hell. So whatever being good earns us, it is temporary. In the end, if the world is simply a complex bundle of material forces, being a Moral person results in nothing.

But such is the religion of postmodern man — denouncing organized religion and Moral Absolutes doesn’t just free him from fairy tales, it licenses him to remake them.

An article in SF Gate touches on this. It portrays one of del Toro’s most popular films, Pan’s Labyrinth, as a synthesis of many religious views. One religious scholar even sees the film as embodying a “broader shift in society’s attitude toward organized religion.”

The theology of “Pan’s Labyrinth” represents a much broader shift in society’s attitude toward organized religion, says Robert Johnston, author of “Reel Spirituality: Theology and Film in Dialogue,” who loved the film.

“Pan’s Labyrinth” “is representative of the turn from religion to spirituality,” says Johnston, professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary, an evangelical Christian university in Pasadena and the largest seminary in North America. “There’s a deep and growing distrust of structures of religious systems and a turn to the construction of personal belief.

Johnston not only observes a “theology” in del Toro’s films, but he sees it as part of “a much broader shift in society’s attitude toward organized religion.” Postmodern culture has caused a shift away from collective, institutional worldviews to more individualized, “personal beliefs.” Notice: del Toro’s rejection of religion did not lead to his abandonment of theology, but his reworking of it. As Tim Keller notes in The Reason for God, “You can’t evaluate a religion except on the basis of some ethical criteria that in the end amounts to your own religious stance” (pg. 10). In this sense, del Toro did not abandon religion; he simply swapped out one for another.

Denouncing organized religion and Moral Absolutes doesn’t just free postmodern Man from fairy tales, it licenses him to remake them.

J.R.R. Tolkien famously saw the invention of Middle Earth and acts of Christian creation as “sub-creation.” He said,

“We have come from God, and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God. Indeed only by myth-making, only by becoming ‘sub-creator’ and inventing stories, can Man aspire to the state of perfection that he knew before the Fall.”

Likewise, C.S. Lewis used his love for mythology to populate his own fairy tales. The Chronicles of Narnia are tethered to a biblical worldview and intended to “reflect a splintered fragment of the true light.”

For the theist, fairy tales are “sub-creations” within a larger Creation, mythologies formed to reflect “eternal truth.” Sadly, the atheist creative can make no such claims.

Which makes Guillermo del Toro a bit of an anomaly.

“When you go to a theater,” he said, “it’s like you’re going to church. You sit in a pew, and you look at an altar…”

While the director is correct about the power of film to invoke inspiration or transcendence, his lack of religious and moral certainty undermines his cinematic brilliance. For if “we all are pawns [in] a battle between good and evil,” then it behooves us to define “good and evil” beyond one’s subjective whim. Which del Toro does not. Though he believes in “a spiritual dimension,” he is hard pressed to impose any moral parameters or religious creeds upon it. But is simply being “a good man” really all there is?

In the end, the reason why Hellboy’s “redemption” was so powerful is because it invoked an “eternal truth” in a real, historically grounded Redemption. The rosary that the tortured demon carries is a reminder of Something bigger, deeper, and truer than his twisted nature. Del Toro’s fairy tales work, in part, because they borrow from the traditional morality and religion they reject.

Yes, the “church” that Guillermo del Toro preaches at is wildly entertaining. However, the postmodern fairy tales he tells only have power insofar as they appeal to the “eternal truths” of their theistic heirs.

September 16, 2021

Video: Intro to Mike’s Art & Writing

Here’s a glimpse into my creative space and some of my process. Thanks to my daughter at Lightframe Photo for assembling this video.

(Link below)

September 10, 2021

Review: “Confronting Injustice without Compromising the Truth”

Francis Schaeffer coined the phrase “Doing the Lord’s Work, the Lord’s Way” in his book No Little People. In it, he argued that “the central problem of our age” is that “the church of the Lord Jesus Christ, individually or corporately, tend[s] to do the Lord’s work in the power of the flesh rather than of the Spirit.” (p. 66).

The problem that Schaeffer describes is at the heart of what Thaddeus Williams seeks to address in his new book Confronting Injustice without Compromising the Truth.

The concept of “social justice” has been around for a long time. For example, death penalty laws date as far back as the 18th Century B.C. King Hammurabi of Babylon codified the death penalty for 25 different crimes. Likewise, many ancient tribes formed moral codes based on ideals of communal health and justice. Similarly, Western culture developed societal ethics founded on Judeo-Christian values. Both the Old and the New Testament are explicit in articulating rules and principles for spiritual and social good.

Williams is definitive about the Bible’s clarion call of social justice. “Social justice is not optional for the Christian,” he writes. “God does not suggest, He commands that we do justice.”

The problem, as Williams notes, is not that the Bible is unclear about what social justice is, but that there are many competing ideas about what social justice should look like.

“…the Bible’s call to seek justice is not a call to superficial, knee-jerk activism. We aren’t commanded to merely execute justice but to ‘truly execute justice’ (Jer. 7:5). That presupposes there are untrue ways to execute justice, ways of trying to make the world a better place that aren’t in sync with reality and end up unleashing more havoc in the universe. The God who commands us to seek justice is the same God who commands us to ‘test everything’ and ‘hold fast what is good.'” (pg. 3, italics in original)

Civil Rights leader John Perkins, writing in the book’s Forward, cautions us that in the midst of “much confusion, much anger, and much injustice… many Christian brothers and sisters are trying to fight this fight with man-made solutions [that] promise justice but deliver division and idolatry [and] become false gospels” (p. xvi). Like Schaeffer warned us, it is possible to “do the Lord’s work” — in this case fighting social justice — in unjust, worldly ways.

“We can’t separate the Bible’s commands to do justice from its commands to be discerning.”

Making this distinction is central to Williams’ thesis. He writes, “We can’t separate the Bible’s commands to do justice from its commands to be discerning.” In fact, this need for “discernment” is essential because of the increasing proliferation of social justice causes and their emphasis in culture.

Numerous fields and institutions have embraced and emphasize social justice causes. For example, many cosmetic brands are now openly engaged in activism, while children’s books like “Woke Baby” and “A is for Activism” are sold alongside Toys for Activism. There’s a Social Justice Glossary and a Social Justice Dictionary for those seeking to hone the lingo. Of course, this emphasis on activism, equity, and social causes has led to absurd over-reach and comical fails. Like the “study” which revealed that white-colored robots are evidence of racism, or the fact that a birth coach was forced to resign for saying only women can have babies. It’s also led to some notable resignations, like Peter Boghossian’s recent departure from Portland State University, claiming that the school “has transformed a bastion of free inquiry into a Social Justice factory whose only inputs were race, gender, and victimhood and whose only outputs were grievance and division.” Likewise, many institutions and organization are becoming “a Social Justice factory,” touting their own advocacies and training employees or students to embrace their approved causes.

But are all these social justice efforts aligned with a biblical worldview?

“The problem is not with the quest for social justice,” Williams says. “The problem is what happens when that quest is undertaken from a framework that is not compatible with the Bible” (p. 7). Thus, Williams proceeds to distinguish between what he calls “Social Justice A” (biblical social justice) and “Social Justice B” (unbiblical social justice). To tease out the differences between these two rivals, Williams proposes 12 questions to assist us in discerning. Those questions form each chapter. They include:

Does our vision of social justice take seriously the godhood of God?Does our vision of social justice acknowledge the image of God in everyone, regardless of size, shape, sex, or status?Does our vision of social justice make a false god out of the self, the state, or social acceptance?Does our vision of social justice take any group identity more seriously than our identities “in Adam” and “in Christ”?Does our vision of social justice embrace divisive propaganda?Does our vision of social justice promote racial strife?Does our vision of social justice turn the “lived experience” of hurting people into more pain?These questions get to the heart of many contemporary social justice causes, and how they differ from Scripture. For while many of these causes hew closely to biblical concerns, they often veer from equally biblical precedents.

Take for example Williams’ first question: Does our vision of social justice take seriously the godhood of God? At its heart, all injustice is a violation of the first and greatest commandment to ‘Love the lord your God with all your heart’ and to ‘love your neighbor as yourself. ‘

“Look deep enough underneath any horizontal human-against-human injustice and you will always find a vertical human-against-God injustice, a refusal to give the Creator the worship only the Creator is due. All injustice is a violation of the first commandment” (p. 18).

From a biblical perspective, all injustice is, first, evidence of our broken relationship with God. True social justice can never be achieved as long as the human heart is disconnected from God. Nevertheless, many social justice causes never take into consideration this gulf between God and Man. Until we make peace with God, there will never be peace on earth… no matter how many causes we platform.

“…the human tree is so hopelessly sick that whatever soil you plant it in, toxic fruit will form. No amount of political revolution, social engineering, or policy tweaking will stop envy, strife, deceit, and maliciousness from sprouting out of our sick hearts” (p. 17)

Not only do we need to discern the spiritual roots of injustice and its address, we must be wise in interpreting data and interrogating claims. Many calls for social justice are based on charges of injustice. But not all of those allegations are necessarily cut-and-dried, nor are their correctives. Even seemingly obvious cases of racial discrimination can be more complicated than they first appear. In his chapter “The Disparity Question,” Williams dissects some common charges of racial disparity. Like the claim that blacks being rejected for home loans at roughly twice the rate of whites is proof of institutional racism. Rather than simply concede that narrative, Williams looks deeper. Couldn’t this fact be due to stark differences in average credit scores between blacks and whites? Especially given the fact that “black-owned banks turned down black applicants… at a higher rate than did white-owned banks” (p. 82)?

Racial disparity can indeed be evidence of injustice. However, Social Justice B (unbiblical social justice) interprets ALL disparities through the lens of systemic racism. As best-selling author Ibram X. Kendi wrote in the New York Times, “racial disparities must be the result of racial discrimination… When I see racial disparities, I see racism” (p. 81). Nevertheless, Williams articulates how the real world is far more complex than this simple formula implies. For example, “twenty-two of the twenty-nine astronauts in the original Apollo space program were firstborns… Asians are underrepresented in the NBA… Women are overrepresented in health-care… Jewish people [received] ’32 percent of Nobel Prizes in medicine and 32 percent in physics’” (p. 82-83). So is racism the best explanation for these disparities? Could other, more complex social and individual dynamics be at play?

Another example Williams gives of disparate outcomes is the percentage of Asian and Jewish students at Ivy League schools. From 2007 to 2011 Asians made up 16% of the student population, while Jewish students made up 23%. However, in the U.S population, they make up only 5.6% and 1.4%, respectively. Williams says, “In other words they’re overrepresented by factors of 3 and 16. Does this prove that the Ivy League is riddled with Asian and Jewish supremacy? Of course not” (85).

In this sense, biblical justice is far more nuanced than contemporary social justice. It does not apply knee-jerk interpretations to data and implement sweeping quota applications to “correct” the perceived disparities. Biblical social justice does not punish one for hard work or intellectual development simply because they belong to a certain demographic tribe. Neither would it refuse promotion or withhold advance from a minority simply because of their skin color or ethnic background.

“The more fully committed we become to a vision of justice in which unequal outcomes are automatically assumed to be the result of injustice, the more our quest for justice will lead, indeed it must lead, to the use of power to enforce sameness. …Different outcomes are the price of freedom. The converse is also true. Tyranny is the price of equal outcomes” (86–87).

Another critical element of unbiblical social justice is its emphasis upon individual, lived human experience. Williams addresses this in his chapter entitled The Standpoint Question: Does our vision of social justice turn the quest for truth into an identity game? Here, Standpoint Theory is called into question. Standpoint Theory is an outgrowth of Critical Theory. According to Pluckrose and Lindsay, it is “the idea that one’s identity and position in society influence how one comes to knowledge” (“Cynical Theories,” p. 117 ). As such, individuals’ experience, especially as it relates to minority and identity particulars like race, economic standing, and gender, become vital. Systems of knowledge are construed that position individuals in or outside of perceived power structures. Thus, elevating “minority knowledge” (meaning ‘truth’ as experienced by a minority class) flips the status quo. As Pluckrose and Lindsay note, “knowledge is inadequate unless it includes the experiential knowledge of minority groups” (p. 196). Not only does one’s individual experience determine what is “true,” but their identity particulars make that unique truth more important to the societal whole.

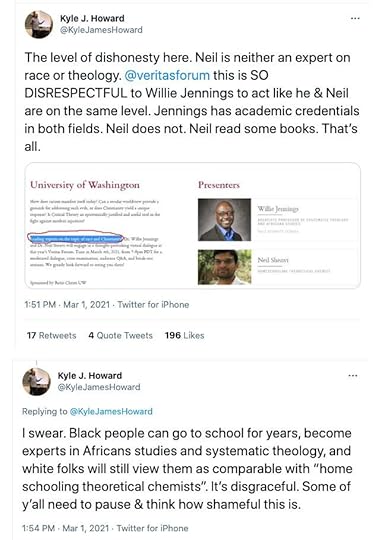

Contemporary Social Justice is deeply tethered to Standpoint Theory. As Neil Shenvi notes, Standpoint Theory claims “that members of oppressed groups have special access to truth because of their ‘lived experience’ of oppression. Such insight is unavailable to members of oppressor groups, who are blinded by their privilege. Consequently, any appeals to ‘objective evidence’ or ‘reason’ made by dominant groups are actually surreptitious bids for continued institutional power.” This is why certain social justicians have made absurd claims about how things like logic and mathematics are simply racist “Western constructs.” Thus, marginalized groups like LGBTQ individuals, American blacks, Native Americans, or the handicapped are seen as having access to unique spheres of insight. As Williams puts it, “Those on the oppressed side of the equation are often granted automatic authority” (p. 156).

But is such a concept biblical? While lived experience indeed taints one’s beliefs and experiences, the Bible does not describe truth as something subjective, something that changes according to skin color or economic status. Williams anticipates such charges:

“Critics will point to my melanin, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, or faith to attack the ideas I am setting forth. There will likely be charges of fragility, blaming the victim, and protecting my privilege. …The problem is that ideas don’t have melanin, private parts, or bank accounts: people do” (PP 153-154).

Through this lens, even Jesus has been cross-examined because He was a Jewish Man. Indeed, some claim that Jesus had to unlearn His own racism and sexism! Such is the logic behind identitarianism and standpoint epistemology. It’s just one of the many reasons we must be discerning as we analyze social justice causes.

We must be cautious critiquing certain social justice claims lest we be perceived as condoning injustice. Tragically, such thinking has led many to withhold the necessary analysis.

Michael Agapito, in his review of Williams’ book at Christianity Today, offered a lukewarm recommendation. His concern was that “some will use it as an excuse to remain overtly comfortable with the status quo.” This critique has proven common among those sympathetic to social justice causes. In other words, we must be cautious critiquing certain social justice claims lest we be perceived as condoning injustice. Tragically, such thinking has led many to withhold the necessary analysis. Williams repeatedly clarified his intent was not to condone apathy. In the preface to his book, Williams writes,

“I care about God, I care about the church, I care about the gospel, and I care about true justice…. Not all, but much of what is branded ‘social justice’ these days is a threat to all four of those things I hold dear” (p. xviii).

Doing the Lord’s work the Lord’s way means being courageous enough to buck worldly trends and push back against unbiblical ideas and solutions. Indeed, history is brimming with stories of injustice procured via the stated cause of “justice.” Genocides, internment camps, lynchings, and gulags have ensued, all under the guise of securing justice. Thankfully, Williams had the courage to push back against the idol of Social Justice.

Confronting Injustice without Compromising the Truth is one of the best books I’ve read on Social Justice from a biblical viewpoint. With social justice now trending, much of it unmoored from a solid biblical worldview, I’ll be recommending Williams’ book often.

July 20, 2021

Writing the “Other” or Writing “Us”

In Storytelling, Portraying Universal Human Experience is Superior to Emphasizing Identity Particulars

In Storytelling, Portraying Universal Human Experience is Superior to Emphasizing Identity ParticularsMy first novel featured a female protagonist. Being that my then writing group consisted mainly of females, the critiques came down pretty hard — “A woman wouldn’t think like that!” they said, or “A woman wouldn’t act like that!” It was an eye-opening immersion into what novelists call “writing the other.”

“Writing the Other” is about walking in someone else’s shoes; it’s about getting into the skin of someone different than ourselves and accurately capturing the emotions, impressions, and experiences of said “other.” Writers must do this all the time. It is essential to good storytelling.

However, in the last decade, “Writing the Other” has splintered into a minutia of identity elements, grievances, and quota tallies. Now, one can find writerly discussions on

While “writing the other” is encouraged, it is laden with cautions and caveats.

While it can, indeed, be helpful for a writer to explore the unique perspective of specific people groups, such attempts often present a minefield for novelists. For example, it is now common to ask whether white authors can write characters of color. The basic idea behind such a query is that “privileged” groups have great difficulty understanding the experiences and emotions of a marginalized people group. Such concerns inevitably spurred a hashtag movement called #OwnVoices which endorses “books about diverse characters that have been written by authors from that same diverse group.” So rather than straight, white, able-bodied writers writing about queer, BIPOC, disabled characters, it is more favorable to platform authors who actually embody their characters’ specific ethnicity, gender, or socio-economic spheres. More recently, controversy erupted surrounding the novel “American Dirt,” an Oprah Book Club selection, because the story about Mexican immigrants to America was written by a white woman. So while “writing the other” is encouraged, it is laden with cautions and caveats.

As a result, the publishing industry has drastically shifted. For one, the demand for “minority voices” has exploded. Now there are publishers who specifically champion people of color. Literary agents are now seeking out authors who comprise various identity groups and write representative characters, like “stories written by BIPOC authors,” “stories that embrace themes such as LGBTQ+ issues, mental health, interculturality, immigration, identity, belonging and race,” and “narratives centering Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), LGBTQ+, and neurodivergent persons.”

However, this shift has not been without negative affect. For example, I spoke to one novelist who developed a story around a minority protagonist. The author was white and hoped to connect with a more diverse audience. The character was conducive to the urban setting and respectful of the diversity guidelines in the industry. “Sensitivity readers” were employed by the author to insure that the character was portrayed true to life. Finally, the story was submitted. However, the editor made a request — the minority protagonist should be changed to the ethnicity of author. Why? Because white authors writing BIPOC is no longer tolerable. Yet the requested changes would require lengthy edits, which the author begrudgingly did. Ironically, upon re-submission, the book was rejected because of its lack of diversity (e.g., white protagonists nor writers were now being sought). Such testimonies, though often left unspoken, are now becoming commonplace in the industry.

This trend of parsing human identities did not originate in the arts. It is the result of a culmination of social, psychological, and academic ideas. On one hand, this thinking is the logical outcome of relativism. The assertion that there is no absolute truth but that individuals perceive and experience life in many different ways leads some to conclude that truth is relative to an individual’s experience. In academia, it’s led to something called “standpoint theory.” In their book Cynical Theories, Pluckrose and Lindsay define standpoint theory as “the idea that one’s identity and position in society influence how one comes to knowledge” (p. 117). As such, individuals’ experience, especially as it relates to minority and identity particulars like race, economic standing, and gender, become vital. Systems of knowledge are construed that position individuals in or outside of perceived power structures. Thus, elevating “minority knowledge” (meaning ‘truth’ as experienced by a minority class) flips the status quo. As Pluckrose and Lindsay note, “knowledge is inadequate unless it includes the experiential knowledge of minority groups” (p. 196). Not only does one’s individual experience determine what is “true,” but their identity particulars make that unique truth more important to the societal whole.