Mike Duran's Blog, page 3

June 18, 2023

Ode to the Bad Dad

My father used to say he was “a good bad example.” But in retrospect, he was probably a better “good example” than a bad one.

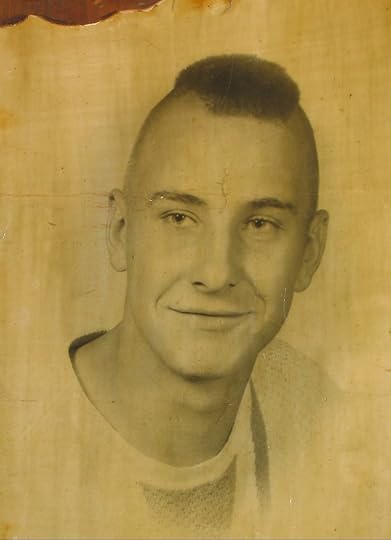

At this writing. he’s been gone 20 years. This pic (to the right) is my favorite photo of him. It hangs in my office. I think it captures both his wild side (mohawks anyone?) and his sweetness. He died of heart failure, mostly due to years of drinking and smoking. He was such an addict. But, in retrospect, he probably shaped me — for better or worse — more than anyone.

Bill Duran worked at a cement plant and became the President of the union for many years. He often proclaimed himself to be for “the little guy.” He was a lifelong Democrat and a flamboyant storyteller; he loved people and worked hard. But his union business consumed him, and he soon spiraled into alcoholism. He would often come home blitzed from a “union meeting,” bust things up, and pass out in his recliner. My mother always worried that his smoldering, unattended cigarettes would burn the house down.

I learned later that he was a byproduct of an awful childhood… information that was hard to come by in our house. One of my aunts recalled finding my father once locked in a closet in his stepfather’s house. Orphaned at an early age, my father grew up on the streets of Monessen, PA, stealing, conniving, and running with packs of ragamuffins. He took up smoking at the age of eight and eventually, was taken in by Catholic nuns. Constantly in trouble with the law, by his teens, my father was given the option to join the service or go to jail. He promptly joined the United States Marine Corps.

Perhaps this is why he and I bumped heads so much. He had difficulty understanding my creative bent, and would sometimes mock me for drawing and writing poetry. I was far-removed from that pack of hardened boys he used to run the streets with. He worked hard to put me through nine years of Catholic school. But my social skills and math scores were well below acceptable. And being I was the firstborn, I received special “motivation” to improve. Corporal punishment for poor grades was, like the holidays, an annual event. By high school, I was carrying the torch he’d commandeered. Drugs, alcohol, and criminal behavior created a palpable tension between us for many years, and eventually led to him booting me out of the house when I turned 18.

No doubt, he saw himself in me and loathed what he witnessed.

Things changed in 1980 when I became a Christian. Despite his unrepentance, I knew I had to forgive him, and did. As Christ prayed for His Father to forgive the executioners because they “knew not what did,” my father had hurt us all because of his own pain.

So it was that in the mid-to-late ’80’s, my Dad admitted himself to a Care Unit for alcoholism. It was the first time in over 20 years that I recall anyone in my family using the word “alcoholic.” But it was also the most courageous thing I ever saw my father do. He remained sober for the rest of his life, became the president of an AA chapter, and helped a lot of people.

I was so proud of him.

Not long after this, my father suffered a massive stroke. As such events go, it happened at my sister’s wedding reception. I rode in the back of the ambulance with him till we reached the hospital, where he became comatose. After several days of scanning and probing, the doctor suggested we consider pulling the plug on him. People in his condition rarely recover. We decided to wait and see.

I would go to the hospital on my lunch breaks and talk to him while he lay there on the ventilator. For once in our lives, I did the talking and he listened. Those were some of the best conversations we ever had! And to everyone’s amazement, he pulled out of it. Of course, the first thing he said upon awakening was to be given a cigarette.

After that, he was a little slower. But his heart had been broken. To my mother’s dismay, he kept smoking. He’d sneak outside in his walker, sit on the porch, and fire up those unfiltered Pall Malls. Yet, after all that, he also seemed to live life more fully. He remained devoted to his AA groups and every Christmas he would dress as Santa Claus for hospitalized kids. And whenever I talked to him about Jesus, he would profess faith, his own unworthiness, and get all choked up. Eventually, his condition worsened and he was confined to a wheelchair.

One afternoon, I received a call from my mother that he’d fallen over and she couldn’t help him up. I drove to their house just to help my father get back up in his wheelchair. Eventually, my mother was unable to care for him, and he was admitted to a nearby assisted-living facility. Being the people person he was, my dad became a hit there. He joked with the nurses and had a reputation for chumming it up with residents. The patio was where he did his smoking, and a contingent of residents would often assemble there to imbibe and reminisce about better days. I’d visit and, sometimes, refer to him as Wild Bill. But his “wild” days were well behind him.

One Thanksgiving, my wife and I packed up some rolls and butter, turkey and gravy, and candied yams. Bringing in “outside” meals was not allowed at the facility. But, like him, I was never much for rules. We weren’t expecting a pat-down, and didn’t get one. My dad’s eyes lit up when he saw some “real” food and proceeded to wolf it down.

It would be the last Thanksgiving I would ever share with my father.

I received the call at work. It was completely unexpected. His organs were failing, and he had lapsed into a coma. I rushed to the hospital, where I found my mother and brother standing on each side of the gurney. My father lay on a ventilator. I nudged my way in and held his hand. We’d been through this before. Only this time, I didn’t feel a need to invite him to pray the sinner’s prayer.

He had made his peace with God.

I kissed him on the forehead and said goodbye.

We buried him in a Hawaiian shirt and played oldies music at his funeral. My son Jon had become his fishing buddy, so Jon made sure to place the old man’s fishing license in the casket. A young Catholic priest from my mother’s parish performed the service. He proclaimed that even though he’d never met William, he knew he was a good man. It puzzled me how anyone could make such a ludicrous statement. But I’d asked to speak, so I got up without any notes or scripting, and just began sharing. Many of my father’s former coworkers were there, as was a significant contingent from the Alcoholics Anonymous group. I told some funny stories and some tender stories. But most of all, I just wanted to say how much I loved him. He was a survivor. And so was I.

I survived him.

Maybe that’s true of all us fathers. We bring so much junk to the table that, looking back, you can’t help but have regrets. Like Jesus’ executioners, I need forgiveness for not knowing what the hell I’ve done. Was my dad a “bad dad”? Of course, Bill would say so. But bad dads don’t stop being dads. And Wild Bill never stopped being mine.

So it’s Father’s Day 2023, and I’m thinking about him. (Is this what aging is like? LOL!) I miss him. He was funny, good-natured, and had a gentle heart. He loved the holidays with all the kids and grandkids. And food. And any show of kindness or affection would cause him to choke up. He used to say he was “a good bad example.” But in retrospect, he was a better “good example” than a bad one. Perhaps one day I could aspire to be the “good, bad example” that he was. Looking forward to seeing him again. I love you, Dad.

April 25, 2023

“Christians & Conspiracy Theories” is Live!

My new non-fiction project, “Christians & Conspiracy Theories: Investigating Alternative Truth-Claims without Buying in to Fear, Fanaticism, or Tribalism,” is now available! Here’s the back cover blurb:

***

The Great Reset. Bigfoot. Anti-Vaxxism. UFOs.Conspiracy theories are no longer a fringe phenomenon. Thanks to the internet and media amplification, conspiracies that were once far-fetched are now mainstream. Talk of a Great Reset and a coming New World Order are no longer isolated claims whispered in obscure internet chat rooms. Cabals of powerful people seeking to fundamentally re-shape our world now openly broadcast their agendas.

Christians are called to be truth-seekers. They are to be discerning of “the signs of the times” (Matt. 16:3) and the “devil’s schemes” (Eph. 6:11). Followers of Christ have long believed in a Plan, a Divine Conspiracy unfolding throughout history; the Seed of the Serpent waging war against the Seed of the Woman. As such, being aware of contemporary conspiracy claims and how to interrogate them, can be essential to a Christian witness.

Nevertheless, some caution Christians against interest in conspiracy theorism. They portray evangelicals as wingnuts, gullible to fake news and fringe beliefs. But is this portrayal accurate? Should Christians avoid researching conspiracy claims just because some go off the deep end? And what about those claims that have been proven true? Should Christians just continue to blindly trust the government, the media, and the “experts”?

This book is about conspiracy theories, and how Christians should interact with them. It’s about becoming your own fact-checker and going where the truth leads you. It’s about fine-tuning your BS-detector and using Scripture as your ultimate conspiracy barometer.

The truth is out there. And it wants to be found.***

You can purchase paperback copies of the book HERE, Kindle copies HERE. Thanks for reading!

April 22, 2023

The Popularity of Exorcism Films Reveals Continued Belief in a Supernatural Worldview

Last weekend, two films about demonic possession released. The Pope’s Exorcist and Nefarious both ended up in the Top 10 weekend box office numbers (3rd and 9th respectively).

Though not all Christians will celebrate such films, much less see them, our culture’s continued interest in the exorcism genre should invoke mild curiosity, if not great interest. Much has been made of Western civilization’s drift away from its Judeo-Christian heritage into, what some have called, a post-Christian era. Not only are social structures becoming untethered from traditional mores, but Materialism has come to dominate our institutions.

Nevertheless, belief that Matter is all there is, and that the Devil and demons do not exist, has not appeared to squelch our intuitive sense that something is out there.

Exorcism films assume a biblical worldview; a world where the Supernatural exists and Spiritual Evil is real. No matter how good or bad these films are, Christians should appreciate that the worldview such films espouse are mostly biblical. No, that doesn’t validate every exorcism film. Nor does it mean that every assumption or portrayal in these films align perfectly with Scripture. It simply means that exorcism films must assume that the spiritual dimension is quite real, that God and the Devil actually exist, and that ultimate Evil is defeated by Absolute Good. To invoke the concept of a Devil is to appeal to the idea of God. Or as the titular character of The Exorcism of Emily Rose said, “People say that God is dead, but how can they think that if I show them the Devil?”

“To invoke the concept of a Devil is to appeal to the idea of God.”

Exorcism also implies spiritual Evil, which in turns implies spiritual Good. And to imply a spiritual dimension is to admit that the world is bigger than what we can see and feel. It also suggests that humans are more than just wetware. This is why, the majority of exorcism films assert an actual demonic entity, not a psychological condition. Yes, some films contain a psychological component to a possession. Films like The Babadook (2014), Smile (2022), and Relic (2020), all mix psychological elements (post-partum depression, mental illness, and dementia) with suggested paranormal phenomenon. However, most exorcism films appeal to the more traditional elements, which in turn reminds us that humans are more than just meat puppets. We are spiritual beings that can be subject to immaterial ideas, elements, and… things.

Also, we should note that these biblical worldview elements are packaged in the horror genre. Many Christians roundly condemn horror films on the grounds that we should focus on Light and Love, not Darkness. As a result, Christian stories have become notorious for being Inspirational and veering away from darker, grittier subject matter. However, demon possession and spiritual evil are indeed topics found in Scripture. To read the Gospels is to encounter both Satan and a Legion of various demons. For this reason alone, such elements should find place in our art and story-telling. Contemporary Romance, Historical Romance, and Amish fiction may have a place. But the horror genre is still the perfect vehicle to address this subject.

Ashley Bell, who starred in The Last Exorcism, put it this way: “Evil has no boundaries. And people are so intrigued by the devil. There’s always that question of, is it out there? And can it be real?” Even the Materialist who has ruled out God, and sees his existence as meaningless, must ponder that question: “Can it be real?” Can unspeakable Evil exist just beyond the boundaries of our sight and sound? And am I vulnerable to it? It is unlikely that an inspirational Christian Romance film will prompt the Materialist to explore that question. But the moment our guy has a smidgen of conviction that the Devil just might be real have a terrible plan for his life? Well, the jig is up. Whether intended or not, exorcism movies might do just that.

January 14, 2023

Excerpt: “Christians & Conspiracy Theories”

I’m having a blast working on my next book: a non-fiction project entitled “Christians & Conspiracy Theories: Investigating Alternative Truth Claims without Succumbing to Fear, Fanaticism, or Tribalism.” Here’s a excerpt from the Introduction. The book is tentatively releasing in the Spring of this year.

~~~

Shortly after converting to Christianity in the Spring of 1980, I met a man who called himself Tabor—Tabor Zebulon. I never learned if that was his real name. In fact, the more I got to know him, the less likely I suspected it was.

At the time, Tabor was visiting his mother. He claimed to live on a piece of property in the high desert of Southern California where he was stockpiling supplies for the coming apocalypse. Tabor looked the part of a religious nut—bushy beard, shabbily clothed, and rather manic. He reminded me of a slightly more docile version of Charles Manson. His message was similarly disturbing.

Tabor believed not only that the Church would see the rise of the Antichrist, the infamous end-times figure of biblical prophecy, but that the contemporary Church was actively being deceived. According to him, the belief in a pre-Tribulation rapture[1], a then common teaching among many evangelical churches, was a tool of Satan to lead Christians astray. For this reason, Tabor was wildly suspicious of organized religion and not shy about articulating his charges against it.

I learned this, rather painfully, after inviting Tabor to share his beliefs with a small group of new Christians whom I was a part of.

His Bible was worn and thoroughly indexed, and when he opened it, he spoke with zeal and authority. As young Christian converts, we offered little resistance to his charges of mass deception. Churches like Calvary Chapel, which we then attended, were paving the way for a great apostacy, he said. When believers suddenly learned that they would not be “caught up” in an invisible “second coming,” as they’d been taught, but would instead face the wrath of the Antichrist, a great “falling away” (II Thess. 2:1-4) was inevitable.

Needless to say, Tabor’s introduction to our group and his message was extremely divisive. Heated discussion followed with one couple even storming out of the meeting.

Tabor soon returned to his high desert compound and, when he did, left far more wreckage among us than he did enlightenment.

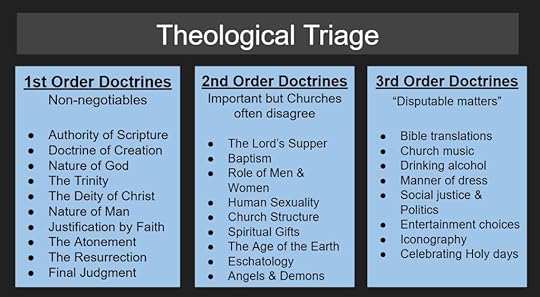

As a growing Christian, learning about alternative views of eschatology inevitably proved healthy. I was theologically hungry and unafraid of debate. Besides, the pretribulation rapture was a central plank of the Calvary Chapel movement. This belief was an extension of a much larger eschatological framework held by the group, something called dispensational premillennialism. [2] Learning about differing positions on the end-times was my introduction to the theological diversity inherent in the Body of Christ. Nevertheless, it was Tabor’s insinuations of mass deception within the Church that had the most corrosive long-term effects on our then-immature minds.

Tabor would become just one of many encounters with conspiratorial thinking in the Church.

Throughout the 1980’s, prophecy and the end-times were hugely popular topics among evangelicals. One could not walk into a Christian bookstore without seeing titles about the Great Tribulation, the coming Antichrist, and the war of Armageddon. For example, Hal Lindsey, the popular prophecy scholar, wrote The 1980s: Countdown to Armageddon, in which he purported that the anti-Christ was already here on earth and would likely be revealed in that decade. Lindsey further predicted that, during this time, Russia would attack Iran in order to gain control of the world’s oil resources, and that the Church would be raptured in 1988. Many popular Bible teachers joined Lindsey in closely monitoring world events and trends, and tying them to eschatological scenarios. Like Chuck Smith, founder of the Calvary Chapel movement, who throughout the 1980’s used world events to insinuate various apocalyptic scenarios. These predictions became part of a long list of failed forecasts about the Second Coming.

Beliefs about looming apocalyptic scenarios and deceptive forces at work to corrupt the Church led to countless conspiracy theories. For instance, Dave Hunt’s polarizing The Seduction of Christianity: Spiritual Discernment in the Last Days, released in 1985. Hunt asserted that heretical beliefs were seducing the Church via the New Age movements, psychology, and the other mind sciences. Along the way, he indicted popular evangelical figures like James Dobson with using humanistic psychological principles that undermined the Gospel. Many Christian counselors, like the then-popular Minrith-Meier Clinics, were similarly indicted. Hunt’s charges would begin a trend in the evangelical world of discernment ministries, much of which continues to this day. At that time, cult-watchers were already quite prolific (led by Walter Martin, the Bible Answer Man). But Hunt and others began to turn their critique upon the Church. Indeed, there was much to critique! However, end times preoccupation and efforts to discern spiritual deception often bred more conspiratorial thinking among believers.

The early 80’s saw the introduction of backwards masking, the belief that subliminal messaging was embedded in some rock music. By playing vinyl albums in reverse, one could allegedly discover Satanic messages. I still recall hunching over my console, manually spinning my Led Zeppelin IV album in reverse, straining to interpret something which might corroborate the claims. Backwards masking was one small part of what is now called the Satanic Panic. The term referred to a moral panic that coalesced in the 80’s and 90’s concerning what was believed to be vast instances of Satanic ritual abuse. Charges of Satanic rituals, secret witch covens, and the incorporation of pagan symbology were ubiquitous among believers. Several self-proclaimed ex-Satanists (like Mike Warnke and John Todd) rose to popularity, claiming that the world system and its institutions were controlled by powerful Satanic cabals. Pagan symbology was often targeted. One claim which gained traction was the allegation that satanic imagery was embedded in the Proctor and Gamble (P&G) logo (1980). [3] It led to product boycotts and, eventually, lawsuits. When the charges arose again in 1995, P&G sued the sources and won a multi-million-dollar claim.

Over the years, I continued to encounter various forms of conspiracism and apocalyptic rhetoric in the Church. Evangelicals were exceptionally vigilant of trends, teachings, and global events that might fit into their eschatological expectations. Sometimes this led to wild speculation and over-reach; other times it led to reasonable, often prescient concerns about societal drift and spiritual compromise.

Nevertheless, some have interpreted the Church’s ongoing attraction to conspiracy thinking as a terrible flaw. In her article at Vox, Why Satanic Panic Never Really Ended [4], Aja Romano suggests that QAnon, and the group’s alleged popularity among evangelicals, is simply an extension of the great moral panic of the 1980’s. (We’ll discuss QAnon and evangelical adjacency much more in Chapter 3.) Indeed, claims that evangelicals are disproportionally susceptible to potentially dangerous conspiracy theories is a repeated claim made by today’s media. For example, popular data site Five-Thirty-Eight ran an article in 2021 entitled Why QAnon Has Attracted So Many White Evangelicals[5]. Ed Stetzer, pastor and missiologist, wrote an Opinion piece entitled Too many evangelical Christians fall for conspiracy theories online, and gullibility is not a virtue[6], while Religion Dispatches bemoaned that ‘Respectable’ Evangelicals Can’t Rein in Conspiracy Theorists.[7] There are many more examples of such charges.

This recent indictment of Christians and conspiracism is part of a larger, growing interest in conspiracy theories and their place in our culture. Social scientists have typically viewed the subject as a fringe phenomenon. Yet beginning in about the mid-nineties, approximate to the growth of the internet, new academic fields of conspiracy research began to develop. For example, the Harvard Kennedy School launched its Misinformation Review in 2020. [8] University of Arkansas began a course titled Conspiracy Theory. [9] Arizona State University opened a new branch of research named Center on Narrative, Disinformation, and Strategic Influence. [10] Numerous universities are now offering “Media literacy courses to combat fake news.” [11]

Some of this new research paints the Church in a very unflattering light. But is the concern founded? Is the seeming increase in conspiracy theories really part of a new “Satanic Panic” among believers? Is conspiracy theorism really endemic among Christians? Are white evangelicals disproportionately attracted to QAnon or similar exotic factions? And is the allure of such fringe beliefs so great that ‘respectable evangelicals’ cannot even rein them in?

But another question emerges at this juncture: Is it automatically wrong for Christians to entertain conspiracy theories?

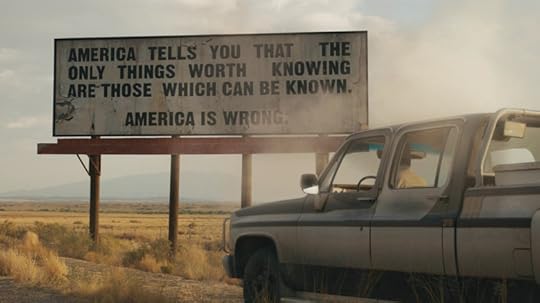

Nowadays, simply asking if vaccines are effective, if elections can be rigged, or if some alien species could walk amongst us potentially triggers the disinfo “experts.” One dare not question the status quo. So should we simply dismiss any exercise in media or scientific scrutiny and embrace everything told us by technicians, journalists, or government fact-checkers? And, if not, how can we do so without being charged with being conspiracists or disinformation peddlers? These are some of the questions I hope to interrogate in the following pages.

Is it automatically wrong for Christians to entertain conspiracy theories? Should we simply dismiss any exercise in media or scientific scrutiny and embrace everything told us by “experts,” journalists, or government fact-checkers?In one sense, considering alternate theories of reality and world events is understandable, if not necessary, for Christians.

The arc of biblical history is conspiratorial. Beginning in Genesis 3, God promised enmity between the “seed of the woman” and the “seed of the serpent” (Gen. 3:15 NKJV). The term “seed of the woman” introduces a Messianic motif into Scripture, a struggle between the offspring of the “serpent” (representative of Satan) and the offspring of the “woman” (representative of Christ). Biblical history chronicles the tension between these forces of good and evil, with the Evil One constantly seeking to thwart the Messianic lineage, ultimately culminating in the titanic apocalypse described in the Book of Revelation. In this sense, all of human history could be viewed as a grand conspiracy between the forces of Good and Evil.

Likewise, the Church has historically believed that powerful, invisible agents are at work in the world around us. The apostle Paul said, “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms” (Eph. 6:12 NIV). A hierarchy of demons and devilish superpowers are ever seeking to deceive the world and draw souls away from their Maker.

Nevertheless, seeing the world as a Satanic system, a network of nefarious invisible forces, is deeply concerning to some. Wouldn’t such claims pre-condition someone to paranoia? In fact, some go so far as to portray the core beliefs of the Christian religion as an elaborate conspiracy theory! In others words, Christianity is viewed by some as an immense, powerful cult held together by unscientific beliefs and fringe-worthy claims. (We’ll explore this more in-depth in Chapter Two.) Nevertheless, as a believer, learning to see this “world system” as hostile to God and part of a complex network of spiritual evil, is essential to helping us live wisely and impactfully. In a sense, conspiracism is a necessary prerequisite for healthy Christian living.

In fact, when describing the end of this present age, Jesus commanded His followers to be vigilant; to understand “the signs of the times” (Matt. 16:3) and to be on guard against deception. “Watch out that no one deceives you,” Christ warned (Matt. 24:4). This end-times deception will be so powerful that it could possibly “deceive the very elect” (Matt. 24:24). Which is why Jesus often said, “Be on guard. Be alert” (Mk. 13:33 NIV).

These appeals for vigilance and discernment were echoed by Jesus’ apostles. The apostle Paul sternly cautioned Christians to “test everything” (I Thess. 5:21) and to be on the watch against “seducing spirits, and doctrines of devils” (I Tim. 4:1 KJV). When speaking of the return of Christ and the Great Tribulation, Paul implored, “So then, let us not be like others, who are asleep, but let us be awake and sober” (I Thess. 5:6 NIV). Likewise, the Apostle John wrote, “Dear friends, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, because many false prophets have gone out into the world” (I John 4:1 NIV).

Conversely, believers are also cautioned to not be consumed with end-times fanaticism. We are to avoid “godless myths” (I Tim. 4:7 NIV) and “an unhealthy interest in controversies” (I Tim. 6:4 NIV). We are to not be consumed by fear, seeing demons (or conspiracies!) behind every bush. Rather, we should “make it [our] ambition to lead a quiet life” (I Thess. 4:11), trusting God for His provision and protection in our new dark ages.

Which implies a balance in our analysis of current events and controversies.

So in a very basic sense, Christians should always strive to be vigilant and discerning. We should be aware of the “signs of times” and “test” the spirits. We should not be naïve or gullible people, but still avoiding unhealthy speculation and unproductive conjecture. Jesus said, “Be wise as serpents and innocent as doves” (Matt. 10:16 ESV). This could relate to how we interact with controversial data or people who believe differently than us. Are we easily swayed and deceived by memes, Facebook ads, or nightly news reports? Or do we “test everything” before reaching our conclusions? Suggestions of election fraud, secret global cabals, or Satanic conspiracism should neither be embraced indiscriminately nor rejected without query. Christians should balance discernment with wisdom, truth with love (Eph. 4:15). In this work, I will describe this as an equilibrium between kneejerk “denialism” (the belief that all/most conspiracy theories are false) and “conspiracism” (the belief that all/most conspiracy theories are true).

Further complicating this balancing act is the media ecosystem we find ourselves in. Not only are we now bombarded with data, algorithms, information, and distractions like never before, but the American media has become one of the least trustworthy of all professions. According to a comprehensive Reuters Institute survey encompassing 46 countries, the U.S. finished dead last in public trust of the media. [12] Even the most credible professions, those of scientists and doctors, have suffered serious compromise and declining trust since the global pandemic. [13]

Now, more than ever, the Christian church needs to be adept in its approach towards conspiracy theories. We must be wise and discerning; courageous enough to not follow the herd, and rational enough to not embrace unfounded, sensationalistic thinking. But how can we be privy to, even investigate conspiracy theories, without succumbing to fear, fanaticism, or tribalism? How can we be vigilant of the signs of the times without developing an unhealthy interest in controversies and speculation? These are just some of the questions I hope to answer in the following pages.

[1] The Great Tribulation is considered by some theologians and Bible students to be a seven-year period of terrible global unrest, or as Jesus said, “great tribulation, such as was not since the beginning of the world to this time, no, nor ever shall be” (Matt. 24:21 KJV). During this time, the Antichrist is believed to be revealed. The Pre-Tribulation Rapture theory purports that Christ will appear secretly and “rapture” all true believers before the Tribulation, who will meet Him “in the clouds” (I Thess. 4:17 NIV), and escape “the wrath to come” (I Thess. 1:10 ESV).

[2] Dispensational premillennialists believe in a seven-year tribulation when the Antichrist is especially active and God pours out His wrath before 1,000 years of Christ’s reign in which the Jewish nation will have a special place and the Jewish Temple will be restored. Israel and the Church are seen as distinct groups within God’s plan. https://www.compellingtruth.org/dispe...

[3] https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles...

[4] https://www.vox.com/culture/22358153/...

[5] https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/...

[6] https://www.dallasnews.com/opinion/co...

[7] https://religiondispatches.org/why-re...

[8] https://www.hks.harvard.edu/faculty-r...

[9] https://honorscollege.uark.edu/academ...

[10] https://news.asu.edu/20210330-global-...

[11] https://www.tun.com/blog/universities...

[12] https://thehill.com/opinion/internati...

Americans’ Trust in Scientists, Other Groups Declines

October 25, 2022

‘The Visitant’ is Now Available!

‘The Visitant‘ was a story I conceived while researching my essay “On Conspiracy Theories and Why Christians SHOULD Be Interested in Them.” During that research, I learned of something called “exit counselors.” These were individuals who specialized in helping people leave cults. Apparently, the rise in disinformation and “fake news” has caused many to fall into extremist tribes. As such, the need for exit counselors has grown. However, my research also led me to conclude that many so-called “conspiracies” actually contain elements of the truth. Anyway, it inspired me to speculate — What would happen if an exit counselor was faced with a conspiracy that proved true? Throw in a government cover-up, a mad scientist, and a ‘non-terrestrial intelligence,’ and you have ‘The Visitant.’

This novella is now live at Amazon and available to download as an ebook. Paperbook books are in process and should be available in a week or so. If you like dark fantasy and noir with Lovecraftian vibes, you should check out “The Visitant.’

September 13, 2022

Publishing Advice for Aspiring ‘Christian Horror’ Novelists

Over the years, I have received a good number of emails from new writers looking for publishing advice regarding their stories. Specifically ‘Christian Horror’ stories. This advice typically revolves around two questions:

Should I publish traditionally or independently?Should I aim for the Christian market or the General market?There are many Christian writers of horror and dark speculative stories who are more prolific and knowledgeable than myself, so these contacts are always a bit humbling. Nevertheless, I try to make it a habit to respond. Being that they come with a certain regularity, I finally concluded it was time to make a more detailed post that would cover those questions and serve as a template for future queries.

***Navigating the publishing industry is certainly par for the course for any writer. But Christian writers often face a unique set of challenges. Not only must we manage the typical publishing questions about platforms, agents, marketing, etc., but we must resolve issues pertaining to our specific genre.

Let’s face it, the “Christian Horror” genre is a unique genre.

While all authors are faced with the option to self-publish, Christian authors must also consider whether to aim for an exclusively ‘Christian’ audience. The decision to publish in the Christian versus the general market is often determined by the content of your stories. However, the Christian who writes horror and darker subject matter faces unique challenges over-and-above the typical challenges faced by those writing traditional ‘Christian Fiction.’

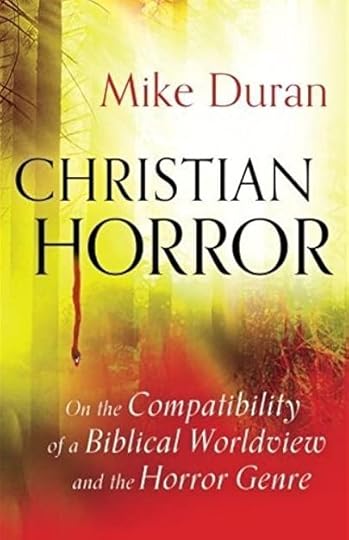

I’ve written more extensively on the compatibility of Christianity and the horror genre HERE, HERE, and HERE. My assumption is that the Christian who writes horror has already wrestled with the theological issues behind that choice. Nevertheless, that author will still find that having an apologetic ready to answer critics and naysayers remains a necessity. This is one of several unique challenges for Christian horror authors. The remainder of this article proceeds under the assumption that the Christian novelist has resolved potential tensions between the horror genre and its compatibility with a biblical worldview.

The Christian who writes horror and darker subject matter faces unique challenges over-and-above the typical challenges faced by those writing traditional ‘Christian Fiction.’

There are many helpful websites and resources for authors. Two of my favorites are Author Media and Jane Friedman. But the choices are vast. Some of the advice that follows will echo what many publishing professionals have better articulated elsewhere. Likewise, this post is not for those looking for more technical discussions about craft, editing, and publishing. What follows is simply my personal publishing advice to Christian horror authors in their quest for publication.

There Is No One-Size Fits All ResponsePerhaps the most common question asked by Christian horror authors is, Should I publish traditionally or independently?

There is much written for authors weighing the options of self-publishing. (See: HERE, HERE and HERE.) In many ways, indie publishing (a term used to describe “any type of publication process that doesn’t rely on a Big 5 publisher“) has been a godsend for Christians who write horror and speculative fiction. In my article, Christian Spec-Fic Titles are Multiplying Thanks to Indie Publishing, I concluded,

Faith-themed fiction titles are multiplying. And indie publishing has fueled that multiplication. The ability to now publish content that the mainstream [Christian] market won’t — whether it’s stories about vampires, vikings, space aliens, dragons, fairies, or ghosts — is playing a part in giving once-unnoticed stories/authors a platform and making Christian publishing “a bright spot” in the industry.

In that post, I recounted my own publishing arc, which may be helpful to those grappling with their publishing options.

My first-ever book contract was with Strang Communications back in 2011. (Strang later changed its name to Charisma House.) I received a two-book deal and an advance for stand-alone novels in the speculative genre (both horror / thriller). The circuit I’d taken to get to Strang was quite wide. My then-agent had shopped my first title, The Resurrection, throughout the Christian publishing industry. While it garnered some interest, the story never found a home, some of that due to its darker subject matter. With limited connections in the general market, my agent and I eventually agreed to part ways. It was a pretty low time in my career. Until I submitted to Strang, which accepted unagented manuscripts, and was offered a contract. (Such is the roller coaster of publishing.)

Indie publishing has been a godsend for Christians who write horror and speculative fiction.

However, with two books traditionally published in the Christian market, I was able to glimpse first-hand the limitations of horror-themed literature there. (I’ll expound on some of those tensions below.) Suffice to say, I was uncomfortable with the echo-chamber the Christian market was becoming. Furthermore, the strictures often associated with the genre — “clean” and “inspirational” stories, no profanity, overt Christian messaging, avoiding darker symbolism and subject matter, etc. — were not conducive to the types of stories and audience I envisioned. At that time, self-publishing technology was rapidly advancing. More and more authors were dropping their agents and opting out of the traditional publishing model. Likewise, the stigma that was long-attached to self-publishing began to fade. Professionally edited books with high-quality art were being published independently.

My first foray into indie publishing struck gold when The Ghost Box, first book in my Reagan Moon urban fantasy series, received a starred review from Publishers Weekly and was listed as one of the best indie titles of 2015. While there are many “Christian” elements to the story — including the lead character having a guardian angel and a cross fused into his sternum — the story is not overtly “Christian.” It contains PG-13 level profanity and occult elements that would be disallowed in the Christian market. In fact, I specifically avoided labeling the book “Christian” in order to reach a different audience and shake being seen as a “Christian fiction” writer.

Clearly, my choice to publish independently worked. However, it was not without cost — both financially and audience-wise.

The author who chooses to publish independently must be prepared to invest significant amounts of time and money into their projects. From cover art, to editing, to advertising, the indie author must be willing to absorb the costs traditionally assumed by the publisher. For example, I invested a minimum of $2,500 into The Ghost Box (cover art, professional editing, ebook formatting, audiobook production, etc.). This did not include purchasing hard copies of the book, bookmarks, promotional materials, etc., etc. While not all of my indie books have been nearly that costly, the self-publishing route requires the author to bear the cost for his or her product. Of course, the upside for the indie author is not just total creative control, but a significantly higher percentage of royalties (typically 70% range, as opposed to 10-15% for trad) as well as retaining the publishing rights to your book.

Conversely, there are various reasons why authors choose the traditional publishing route. One is having industry professionals attached to your project. Not having to invest in cover art, editing, or printing is a huge relief for many authors. Also, being published traditionally can provide the author a wider birth of distribution. Many indie authors struggle to get their books into actual bookstores. For example, my local Barnes & Noble carries my first two trad published books, but refuses to carry my indie books (per a company-wide policy regarding self-pubbed books). Nevertheless, both the trad published and indie published author must work to market their material. Some are under the impression that trad publishers assume all the marketing for your book. This is not true. In fact, many such publishers will not take on authors who do not already have sizeable platforms. Another downside to traditional publishing is adherence to the publisher’s guidelines and correctives. Many authors’ joy at being picked up by a trad publisher is tempered by a publisher’s request to alter a story or character in ways that water-down an author’s creative intent.

So when it comes to the decision between traditional or indie publishing, there is no one-size-fits-all answer. The author must answer numerous questions. How big is your existing platform? How active are you on social media? How large is your professional circle? Do you have established authors who can endorse and/or guide you? Are you able to absorb the costs of self-publishing? Does your genre fit with current market trends? Is your story more niche than mainstream? How able and willing are you to market yourself and your books? Are you willing to wait — often years! — to solicit agents and publishers? Are you willing to release creative control of your books over to others?

These are just a few of the questions facing an author. And while the indie publishing option is not unique to Christian horror authors, it does often uniquely influence their decisions.

The Christian Market vs. the General MarketFor many Christian horror writers, the choice to publish independently is directly tied to the makeup of the traditional Christian market.

Of the 19 Top Christian Fiction Publishers, only a small percentage of novels could be labeled as “horror.” In fact, in my book Christian Horror: On the Compatibility of a Biblical Worldview and the Horror Genre, I cite a publishing insider who admitted that Christian publishers specifically avoid the term “horror.” Even though they may acquire stories that fit in that genre, they will substitute labels like “suspense,” “thriller,” or “chiller.” This aversion to the term — and the genre! — of “horror” by Christian publishers is a troublesome reality for many Christian horror authors.

The Christian fiction market comprises a rather narrow subset of the publishing field. While Christian publishing (this includes non-fic titles) continues to maintain a relatively strong niche, Christian fiction is another animal entirely. The industry is dominated by Women’s Fiction, Historical Romance, Prairie Romance, Cozy Mystery, and Christian Suspense. Inspirational fiction is the norm (meaning stories with a positive, redemptive, edifying message). Not only is its demographic reach quite narrow (predominantly white, middle-aged, evangelical women), but its content guidelines are exceptionally strict.

I experienced this first-hand with my early “Christian” publications. Not only did I receive pushback from Christian reviewers who felt my content was too dark, especially as I employed occult symbols and references, but my publisher required me to nix certain language. This often led to humorous discussions. (For instance, the word “crap” was tolerable because the word is derived from a real person, a plumber who was integral in the development of the flush toilet named Thomas Crapper. Then there was inclusion of the word “flippin’.” Even though both “flippin’” and “friggin’” are substitutes for the F-word, “friggin’” sounds closer to the actual word, so is not allowable. Nevertheless, the publisher forbade me from using the phrase “go to hell,” even though it was directed at a spirit.) Such are the decisions faced by trad-published authors.

This also extends to speculative and horror content. Early in my career as a writer, I pitched a “Christian vampire” novel. At the time, the Twilight Saga was all the rage, so my story garnered some interest among publishers. The protagonist would be a believer who’d learned (via faith and science) to transcend his urges, subsequently gathering around himself night creatures who also sought to pursue good. However, the more I floated the idea, the more pushback I received from some Christian readers. Vampires can’t be good, they objected. The historical archetype should be maintained.

From dragons to vampires to zombies to ghosts, horror authors will find common tropes often anathematized in Christian fiction circles.

The longer I interacted with Christian writers and readers, the more I learned that certain tropes, characters, archetypes, and myths are off-limits to many Christian authors. For instance, debates about the use of magic in one’s stories, occult symbolism, and spell-casting are typically lively among believers. Some ask, Can Christian Writers Include Magic in their Fantasy Novels? Others ask Is it Okay For Christians to Tell Ghost Stories? Some have even argued that zombies should be off-limits in Christian fiction. From dragons to vampires to zombies to ghosts, horror authors will find common tropes often anathematized in Christian fiction circles.

When deciding between markets, the Christian horror writer must consider the strictures and/or creative freedom each market allows. The author whose religious content is explicit, and who has no qualms complying with the traditional content norms, should consider aiming for the Christian market. Conversely, the author who writes grittier, darker fare that contains language and/or doesn’t fit neatly into a “Christian” box should consider aiming for the general market.

In my interview with Jason Sizemore, founder of Apex Publications, I asked him what advice he’d give to Christian authors who enjoy speculative stuff but struggle with the “ultra-conservative strictures” of the current Christian market. He answered,

My suggestion to the writers who frequent your site is to repackage their work. Don’t market it as faith-based. Use words paranormal fantasy and religious horror. Describe it as having a bit of an edge. That should boost you out of the ultra-conservative gutter.

Please note: Jason’s advice was not to strip the story of religious elements but to “repackage” it. This distinction is important and points to a fundamental struggle for the Christian horrorist: The issue is the market, not religious content.

And this issue of content is perhaps the most important factor in deciding between markets. In my post, Why I Decided to Write for the General Market, I listed several different reasons for my decision to leave the Christian market in favor of the general market. I concluded:

I want to write stories that contain spiritual themes and religious content but remain free to noodle around with weird science, un-orthodox ideas, unholy characters, who sometimes think bad thoughts and use bad language.

And that’s pretty much my bottom line. While I’m a Christian, write from a Christian worldview, and riddle my stories with religious themes, I also like to explore characters and themes that do not fit comfortably within the traditional Christian market.

Be Prepared for Pushback and Misunderstanding from Both SidesIt is not uncommon for Christian horror authors to receive pushback and critique from both sides of the aisle — secular readers who object to a story’s religious content and Christians who object to a story’s ‘secular’ content. In this sense, the Christian horror author must be prepared to get hit from both sides.

It is not uncommon for Christian horror authors to receive pushback and critique from both sides of the aisle — secular readers who object to a story’s religious content and Christians who object to a story’s ‘secular’ content.

For example, I recently received a one-star rating for my book The Ghost Box on Amazon. The title of the reader’s review was “Christian book with foul language to boot.” The reviewer writes:

I give it a one star because well for a so called Christian book it has the worst language ever. I mean really this book could have been written by any secular author out there and you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. I really don’t know the reason for the foul language it’s not like it was needed and it didn’t add anything to the book.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about this review is the attribution of “Christian book” to The Ghost Box. Nowhere have I labeled the book as “Christian fiction.” Nor do I consider it such. Which leaves me to wonder why the author concludes this. Most likely, my canon betrays my worldview. With two books published in the Christian Fiction market, a book entitled “Christian Horror,” and a spiritual memoir recounting my conversion to Christianity and my time in the ministry, such conclusions are inevitable. Likewise, social media breadcrumbs may inevitably divulge an author’s religious worldview, exposing their stories to unexpected critique. God forbid readers discover an author is a Christian, a Republican, a homeschooler, or a conspiracy theorist!

Conversely, the Christian author publishing in the general market must also face the possibility of religious objections to their stories. Again, an example from my own experience. This Amazon reviewer named Hannah, objected to my novella Wickers Bog: A Tale of Southern Gothic Horror on my portrayal of religion, specifically that I was too “pushy.” She writes,

With frequent mentions of God and a big emphasis on fate, I had a hard time not feeling like this story was pushy. That said, it’s a common thing in southern gothic. Religion has a strong grip on the south, both its characters and its writers. I’m not exactly surprised, but the methods used here irritated me. Again, it’s difficult to explain in-depth without spoiling the story, but the main character’s ending thoughts had me rolling my eyes. If you’re like me and came from an abusive religious background, you might want to skip this one.

I don’t want to seem excessively harsh just because the story has a Christian slant. There is a lot of good here. The writing is solid, the imagery is nice, and the climax is pretty thrilling. I think the author is an excellent writer, and some of the problems vanish if you read this as a ghost story, not as a mystery. The imagery took me right back to my childhood, and if you love a good spooky tale, this could be a quick fix. However, the twist is weak, and the religious themes become increasingly heavy-handed towards the end. If the book became as pushy about Christianity earlier on as it became by the end, I would not have finished it.

All in all, the review is mostly fair. Yet despite the “solid” writing and a “thrilling” climax, Hannah only gives Wickers Bog two stars (out of five). Apparently, the religious themes are so “heavy-handed” that someone who came from “an abusive religious background” should consider avoiding the book.

Critique is par for the course for novelists. The writer who is overly sensitive to bad reviews might reconsider a career in writing. This is especially true for the Christian horror novelist. For not only must they be prepared for Christian readers to find their stories not “Christian” enough, they must anticipate other readers finding their stories “too Christian.” Some of that critique may be fair. Some might not. Nevertheless, the Christian horror writer must be prepared for pushback from both sides.

***Of course, there are many more questions and issues for the aspiring Christian horror novelist to grapple with. Hopefully, this post can serve as a helpful introduction for some.

The real divide in the “Christian horror” debate is not between whether the horror genre is compatible with Christian fiction, but whether Christian horror is compatible with the current religious market. Again, the Christian horror writer should be resolved about the theological tensions before they can effectively grapple with the market demands. My hope is that some of my advice and experience can help other aspiring horror authors to prayerfully navigate the complexities of both their calling and the publishing world.

August 9, 2022

The Bible is Unequivocally ‘Pro-Life’

When Christians claim to be both ‘pro-choice’ and ‘pro-life’ they betray ideological bias and ignore the broader teachings of Scripture

When Christians claim to be both ‘pro-choice’ and ‘pro-life’ they betray ideological bias and ignore the broader teachings of ScriptureIn an Opinion piece entitled Does life start at conception? That’s not what the Bible says, Christian novelist Matt Mikalatos defended a “pro-choice” position regarding abortion. From the article:

“Given that the Bible is less than clear about exactly when life begins, I — like many Christians — am pro-choice, even though I’m anti-abortion. Pregnant people should be able to make this often difficult and painful decision with their doctors, their loved ones, their counselors or religious advisors.”

Massacre of the Innocents by Luca Giordano (1634-1705, Italy)

Massacre of the Innocents by Luca Giordano (1634-1705, Italy)Being personally pro-life but politically pro-choice is becoming a common approach to the topic of abortion. Sadly, many Christians have adopted this stance. However, that approach is problematic at best, hypocritical at worst.

The main argument offered by Mikalatos for holding such a position is that the Bible is unclear about when human life starts. Psalm 139 is his first target.

The go-to Bible passage for proving that life begins at conception is Psalm 139, a song written by Israel’s King David. David says, “For you formed my inward parts; you knitted me together in my mother’s womb.” And, “My frame was not hidden from you, when I was being made in secret, intricately woven in the depths of the earth. Your eyes saw my unformed substance; in your book were written, every one of them, the days that were formed for me, when as yet there was none of them.”

The translation from Hebrew to English has obscured some specificity, though. If we’re going to treat this passage as a scientific fiat about the beginning of life, we need to look at it more closely. The word translated “inward parts” is the Hebrew word for “kidneys.” The ancient Hebrews believed the kidneys were the seat of our deepest emotions. However, if we’re going to read this passage for insight about when life begins, kidneys don’t start forming until the fifth week post conception, and they don’t start working until the beginning of the second trimester.

Likewise, in verse 15, David says his “frame” was not hidden from God. The actual word here is bones. A fetus’s bones start to harden at week 13, right around the same time the kidneys start functioning.

Growing up in evangelical — largely Baptist — churches, I was taught that the most important thing in interpreting the Bible is context. In context, Psalm 139 isn’t about babies, or conception, or when life begins. It’s about how God knows our deepest, most hidden feelings, knows where we run away to, knows us better than anyone else. (Bold, mine)

Mikalatos may be correct in concluding that Psalm 139 is not “a scientific fiat about the beginning of life.” However, to suggest that Psalm 139 “isn’t about babies, or conception, or when life begins” is a dangerous leap.

In his essay, The Sanctity of Human Life in the Womb – Psalm 139, pastor Ray Fowler covers similar ground… but reaches very different conclusions. He writes:

The Hebrew word for “inmost being” here is actually the word for “kidneys,” which probably sounds a little strange to us at first, “O Lord, you created my kidneys.” Well, God did create our kidneys, but that’s not what David is talking about here. In those days when you dismembered an animal, the kidneys were the very last organ you would reach, and so in Hebrew thought the kidneys came to represent the innermost part of the person, your very inmost being. Nowadays we use the word “heart.”

Fowler concludes,

God created your inmost being, not just your physical self, but your soul or your spirit as well. Human beings are not just physical beings. We are much more than just biology and chemistry. We are much more than just animals. From the very time of creation God distinguished human beings from all other animal life. Genesis 1:27 tells us that “God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” And so we are persons created in the image of God. We have personality; we have the gift of speech; we have a moral nature. God not only created your physical body. He also created the person inside – your inmost being. (Bold, mine)

Whereas Mikalatos interprets Psalm 139 as simply meaning “God knows our deepest, most hidden feelings,” Fowler interprets it as confirming the wonder of God forming every human being in His very image. This is a crucial distinction.

The Bible may not be absolutely clear about when life begins, but it is absolutely clear about what that life is, and why we should approach it with the utmost of dignity and respect.

The distinction between biological life and spiritual, or soulish, life is what many “pro-choice Christians” use to justify their position. They argue that because no one knows exactly when a fetus becomes a soul or a person, abortion on demand should be permissible. As Mikalatos puts it, he is “pro-choice” because “the Bible is less than clear about exactly when life begins.”

But while the Bible may not be absolutely clear about when life begins, it is absolutely clear about what that life is, and why we should approach it with the utmost of dignity and respect.

God confers infinite value upon the developing human being. For example, in Exodus 21:22-23, God included protection for the unborn in His Law. If a pregnant woman was injured, causing her to lose her child, then the one who caused the injury was to be executed. Why? “A life for a life” (vs. 24). That phrase, and the prescriptive punishment, reveals that God considers the life of the unborn just as valuable as that of a grown man. In God’s estimate, the unborn, developing child is just as valuable as the fully formed. He makes no value distinction between the two.

Even non-Christians acknowledge this. For example, Nat Hentoff was a Jewish atheist. He was also a politically progressive civil libertarian. He said this:

Once the sperm and the egg meet, and they find a sort of nesting place in the uterus, you now have a developing human being. It’s not a kangaroo. It’s not a giraffe. It’s a human being. And that development in the womb until the person comes out is a continuing process. Therefore, if you kill it at any stage–first three weeks, first three months—you’re killing a developing human being. (Bold, mine)

While the Bible may not tell us exactly when a fetus becomes an actual human being, science does. 95 percent of biologists agree that human life begins at fertilization. Hentoff is right: Abortion at any stage in the pregnancy is the termination of “a developing human being.”

This is why many early Church leaders and faith communities believed that abortion was a great moral evil. One such document, the Didache, one of the earliest Christian documents in possession, specifically addressed the subject. In his article, Notes From The Didache On The Early Christian View Of Abortion, R. Scott Clark expounds upon Didachean texts concerning abortion.

This passage should give pause to those self-identified Christians who glibly announce that they are pro-choice. The Didache was not indifferent about abortion nor does it hesitate to list abortion (and infanticide) with other gross violations of the natural and moral law: murder, adultery, pederasty, sexual immorality, magic and sorcery, coveting, perjury, greed, and conspiracies (2:1–7). The pagans were known to try to induce abortions, which the Didache prohibits. It is hard to imagine the author of the Didache announcing that he is personally opposed to abortion but supported it as a matter of public policy any more than they would say the same about murder of adults, pederasty, and the like.

The Bible may not be absolutely clear about when life begins, but it is clear about what that life is – it’s a human being made in God’s image. And being created in God’s image confers infinite worth upon the unborn human.

Of course, the “pro-choice Christian” will argue, “But we don’t know when God’s image is actually placed into the human being.” From there, they shrug and defer the “difficult decision” to the mother. Appealing to biblical ambiguity regarding the “ensouling” of the unborn child becomes a simple way to avoid taking a stand.

However, the distinction between a soulless fetus and an “ensouled” child is not one the Bible makes. Rather, Scripture affirms that God is intimately aware of the unborn person, miraculously fashions their physical being, and stamps them with His very own image.

The distinction between a soulless fetus and an “ensouled” child is not one the Bible makes.

When Christians claim to be both ‘pro-choice’ and ‘pro-life’ they betray ideological bias and ignore the broader teachings of Scripture. By keeping one foot in the pro-choice camp and the other in the pro-life camp, these believers can elicit cred from political liberals and not offend the “worldly,” while still professing allegiance to Christ and His Body. It’s a dangerous middle to maintain.

Yes, there are many complexities to the abortion issue. And of course, Christians must exercise grace and compassion to those who wrestled with the choice to abort. However, citing biblical ambiguity as a license to claim the “pro-choice” label, is at best, inconsistent. At worst, it’s a blatant misuse of Scripture and a defaming of the sacredness of human life.

July 7, 2022

Biblical Themes Found in Contemporary Folk Horror

Christian themes and biblical imagery contribute greatly to the contemporary horror genre. Whether it’s Catholic exorcists, angels and demons, end-times apocalypse, or visions of Hell, religious themes are replete in today’s horror. Folk horror is no exception.

Folk horror uniquely appeals to specific biblical themes. In this article, I hope to outline some of those theological themes and how they overlap with that contemporary genre.

What is Folk Horror?The term “folk horror” is relatively new, a phrase that was popularized in the early 2000s. Over at TV Tropes, folk horror is categorized as a subgenre of religious horror.

This subtrope of Religious Horror is less concerned with organized faiths and divine beings as much as it’s concerned with the old folkloric rituals in isolated rural areas. Thus, while it can still focus on a modern religion, it is more likely to focus on the pagan faiths of yore. Demons, cults and goblins haunt the woods while regular people try to survive. Organized religion is most likely corrupt and/or useless, though sadistic clergymen can be the true danger. If you’re lucky, you’ll have one heroic Badass Preacher among the whole lot, but it might not do any good against beings much older than any god we know.

“Pagan faiths” are often a centerpiece of the folk horror genre. The word “pagan” was used by early Christians to describe polytheistic Romans. Much folk horror features various forms of paganism or old world religion, contrasted against contemporary religion. For example, the 1973 classic “The Wicker Man” pits a devout Christian detective against the inhabitants of an island village that has abandoned Christianity for a form of Celtic paganism. Likewise, Robert Egger’s “The Witch” (2015) follows a Puritan family, exiled from religious fellowship, whose rural isolation leads to contact with witchcraft. In both cases, there is a natural dichotomy between Christian monotheism and old world paganism. In this way, folk horror is often juxtaposed against traditional Christian beliefs.

While the Crusades morphed into a purging of paganism from the land, stories of witches and devils inevitably flourished. Practicing pagans were forced into secrecy. Some withdrew into isolated countrysides and forests to ply their occultism without interference. Thus, belief in haunted forests, cursed springs, and sacred groves populated the ancient mythological landscape. For this reason, one of the thematic constants of folk horror is its portrayal of Nature or rural isolation as something to be feared.

Fear of the WildernessIn his essay on folk horror, Michael Gold distills its essence into a “fear of the wilderness.”

…stories about witches, monsters, and other bizarre phenomena continued in the folklore of the region, as it had all around Europe. Sometimes this expressed itself in a kind of double-belief, or folk belief, like the rural communities in the Alps who dress like monsters to steal away maids as part of a Christmas celebration. Or the fact that many Icelanders go to Church on Sundays and leave gifts for elves the rest of the week. Usually, however, this expresses itself as a kind of fear of the wilderness. Witches, crones, and Baba Yagas are vestiges of a lost Europe, one where magic and connection to nature reigned supreme, one where sacrifices to the Gods were necessary, and sometimes hard to stomach. These stories not only stemmed from cultural memories of the old religion, they also stemmed from the occasional confirmation that deep in the woods there was some community or another that simply never got the memo.

In many ways, urbanization and technological advance have only heightened our fear of the wilderness. As we have become more reliant on technology and modern amenities, Nature has in turn become more alien to us. We are at home in the mall or apartment, but stranger to the field or forest.

As we have become more reliant on technology and modern amenities, Nature has in turn become more alien to us.

In The Harrowing and Hypocritical Humanity of Folk Horror, Peyton Robinson writes, “Nature’s familiarity is rendered eerie and untrusting.” He concludes that folk horror is

…most aptly recognized by its utter isolation. Usually set in a rural location, folk horror is marked by either the dark spiritual power of the land, a community that exists on the fringe — with their isolation breeding a ‘wayward’ set of beliefs, religions, and practices — or both. Nature’s familiarity is rendered eerie and untrusting. It all rests on the terrifying assertion that the familiarity of the land and people who surround you are a grim mystery with dark, damning truths.”

This rendering of Nature as alien and primal is ubiquitous in contemporary folk horror. For example, the 2017 British horror film “The Ritual” follows a group of friends whose trek through the woods of Northern Sweden leads them to a cult which worships an ancient Nordic deity — part animal, part plant, and part human. Similarly, “The Apostle” (2018) features a religious commune that inhabits an isolated island and worships a nature goddess comprised of flesh, rootage, and foliage. In both these cases, the protagonist’s’ journey away from civilization leads them to a collision with some vile offspring of Nature.

In these, and many other cases, the monstrous elements of the plot are but manifestations of the wilderness and isolation. Not only does the wilderness house dark and primal energies, but the Land is seen as a monstrosity all its own.

Likewise, Scripture portrays Man as existing in an uneasy alliance with Nature. Whereas the early chapters of the Bible reveal Creation as “good” (seven times in Genesis 1 God pronounces His creation ‘good’), the Fall of Man (Gen. 3) introduces corruptive elements. Not only does the Land begin to produce “thorns and thistles” (Gen. 3:18), but Adam and Eve are driven from the Garden they were commissioned to occupy.

The entire story of Scripture is that of Man living outside the Garden and pining to return. The Wilderness is alien because we are exiled from Eden.

In this sense, the fear of the wilderness contained in much folk horror can be seen as a broader alienation of Man against Nature. We are exiled from the Garden, refugees from our intended Estate. Not only does Nature produce “thorns and thistles,” corrupting our former home, but we stand cursed outside Her confines.

The Land as Enemy / AdversaryIn his article What Can Folk Horror Tell Us About Our Landscape?, Adam Covell writes,

Folk Horror of all types requires some sense of a remythologised landscape. By this I mean that the characters must in some way believe that what they do to the land, for the land or what comes from the land is beyond and above them in some way. Many characters and societies within Folk Horror believe in such power of landscape though usually in a negative, horrific sense. The most famous example of this occurs in The Wicker Man where a man is burnt to death in order to propagate the island’s previously failed apple crops.

Indeed, “The Wicker Man” frames the Land as ‘adversary,’ not in the sense that Mother Nature actively stalks humanity, but that she requires obeisance from us. In the case of that film, the inhabitants of the island shed blood to satiate the Earth’s crops. Human sacrifice as Earth homage is a thematic mainstay in folk horror.

The fear of the wilderness contained in much folk horror can be seen as a broader alienation of Man against Nature. We are exiled from the Garden, refugees from our intended Estate.

For example, Thomas Tryon’s “Harvest Home” (1973), which is widely credited as the inspiration for Stephen King’s “Children of the Corn,” revolves around the corn harvest and innocent outsiders drawn into a rural cult. However, the key to the villagers’ bountiful harvests involve pagan rituals and human sacrifice. “The Hallow,” a 2015 British-Irish co-production filmed in Ireland, includes the tag-line, “Nature has a dark side.” In the article, The Resurgence of Folk Horror, the author suggests that this tagline “is perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of folk horror: Nature is no longer content to be background. Nature has power, agency, in folk horror. It lives, moves, acts, overpowers, destroys.”

When She is not demanding sacrifice, Mother Earth is exacting judgment. As in “Gaia,” a 2021 South African ecological horror film, in which a nature god assimilates humans into the forest, turning them into flowers, fungus, and even trees. In a more aggressive turn, M. Night Shyamalan’s poorly-received “The Happening” (2008) pits Man against Nature, literally. After a series of mass suicides, the protagonists speculate that plant life has developed a defense mechanism against humans causing the release of an airborne toxin which stimulates neurotransmitters and causes humans to kill themselves. Numerous iterations of Nature vs. Humanity can be found in folk horror, causing some to even suggest that, in the genre, we are actually the villains.

Again, the idea of Humanity living in an antagonistic or adversarial relationship with Earth is quite biblical. In Scripture, the Man himself is formed from the Earth (Gen. 2:7). The very first job ever assigned to him was gardening. God placed Adam in Eden and commanded him to “till the earth and keep it” (Gen 2:15). Furthermore, the Lord commanded Man to steward and rule over creation.

And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” (Gen. 1:28 ESV)

However, the Fall of Man disrupted his relationship to Earth. Not only is the ground “cursed” (Gen. 3:17) because of him, but “thorns and thistles” (Gen. 3:18) emerge, choking out ecological tranquility. Sin created a rift between Humans and the Planet.

The Bible often describes this fractured relationship between Humanity and Creation in stark terms. For example, God commanded His people to resist the pagan practices of the surrounding nations lest they “defile the land.”

Do not defile yourselves by any of these practices, for by all these things the nations I am driving out before you have defiled themselves. Even the land has become defiled, so I am punishing it for its sin, and the land will vomit out its inhabitants.

But you are to keep My statutes and ordinances, and you must not commit any of these abominations—neither your native-born nor the foreigner who lives among you. For the men who were in the land before you committed all these abominations, and the land has become defiled. So if you defile the land, it will vomit you out as it spewed out the nations before you. (Lev. 18: 24-28 NIV)

So according to Scripture, not only can certain human actions defile the land, but the land can wage retribution (“it will vomit you out”). Things like ecological disaster, war, and bloodshed can be seen as desecration of the Land. After Cain murdered his brother, God said, “What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood cries out to Me from the ground” (Gen. 4:10).

Likewise, much folk horror taps into our uneasy relationship with Creation. The ground has been “cursed” because of our sins, whether it be through ecological disregard or spiritual defilement. Just as Abel’s blood cried out from the soil, so our sins find us out. Folk horror often taps into our uneasy symbiosis between the Earth we were formed from and our delinquent stewardship.

Deifying NatureIn The Resurgence of Folk Horror, Dawn Keetly notes how the genre often frames the Earth as a sentient being full of “lively forces at work around and within us.”

While the most overt source of conflict in folk horror is religious—between Christianity and paganism—I think that the less overt yet actually much more important conflict involves humans and their natural environment. In folk horror, things don’t just happen in a (passive) landscape; things happen because of the landscape. The landscape does things; it has efficacy. Jane Bennett (a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University) puts this idea beautifully, describing the long tradition of philosophical materialism in the West, in which “fleshy, vegetal, mineral materials are encountered not as passive stuff awaiting animation by human or divine power, but as lively forces at work around and within us.” Folk horror is about these “lively forces”—the “fleshly, vegetal, mineral”—in their most threatening incarnations.

Whereas Scripture describes God as being separate from Nature, paganism often equates Nature with God. Though not folk horror, James Cameron’s “Avatar” is often considered an ode to pantheism. Ross Douthat, in his NY Times’ article Heaven and Nature, described the 2009 blockbuster film as “Cameron’s long apologia for pantheism, a faith that equates God with Nature, and calls humanity into religious communion with the natural world.”

Paganism and pantheism share many of the same ideological and religious spaces, which is one reason why folk horror often embraces a more pantheistic view of Nature. In their review of “Gaia,” the folks at Grimoire of Horror summarize the film this way: God is Real, and She’s a Fungus. Another example could be Ben Wheatley’s “In the Earth” (2021). The story focuses upon ecological researchers who learn of the legend of Parnag Fegg, the Spirit of the Woods, a nature spirit who is influencing the team and using the environment to communicate with them.

Part of the religious tension that occurs in folk horror is between the “old gods” and the one true God, Christianity and paganism, the God who made Creation vs. the god who is Creation.

Jewish commentator Dennis Prager writes

Indeed, of all the false gods, nature is probably the most natural for people to worship. Every religion before the Bible had nature-gods — the sun, the moon, the sea, gods of fertility, gods of rain and so on.

Whereas the Bible commissions us to steward the Land, it forbids us from deifying it. Indeed, one of the traits of the pagan world was its elevation of Earth to the level of godhood. Rather than just cultivating trees and using them for beauty or utility, some reverenced them, bequeathing upon the Land consciousness and cognizance. In fact, panpsychism – the theory that everything has consciousness – is undergoing a surprising renaissance, even in academic and professional circles. Nevertheless, Scripture is clear that worshipping and serving “the creature rather than the Creator” (Rom. 1:25) is the most reprehensible of all sins.

Which is why the Bible commands us neither to denigrate nature nor deify it.

This also explains why much of the religious tension that occurs in folk horror is between the “old gods” and the one true God, Christianity and paganism, the God who made Creation vs. the god who is Creation.

It’s also why the original “Wicker Man” is typically viewed as a classic in the genre. One reason for this is the continued rise of paganism. The original film took painstaking care to research and represent ancient pagan practices and rites, including the burning of the Wicker Man effigy at the film’s climax. But whereas paganism was once considered archaic and in decline, a vestige of primitive man’s ignorance and fear, (which made the thriving pagan cult in the original film such an anomaly), it has recently resurfaced with striking vigor. (See my article on the rise of Pandemic Paganism and the exponential growth of witchcraft, Wicca, and occultism.)

But another one of the original film’s strength is in its portrayal of the antithetical nature of paganism and Christianity. This is a very important point. Pluralism has forced us into the position of drawing less distinctions between religions. Nowadays, it is not uncommon for people to see once incompatible religions (such as Christianity and paganism) as part of some vast mythological umbrella. Christianity is just one of many ways to god, people regurgitate without thought. In this sense, the film does a number of things that is rather difficult to pull off nowadays — it portrays a distinct difference between paganism and Christianity. A distinction, in fact, that has deadly consequences for one of the parties. Not only does The Wicker Man serve as a warning against spiritual naivete and complacency, it illustrates the stark, very real differences between world religions.