Greg Cummings's Blog, page 3

October 14, 2016

Lost At Sea

At daybreak on 4 November 1587 the King of Spain’s great Manila galleon, the Santa Ana was in sight of Isla de California. It was a crisp, clear day, without a single cloud in the sky. Tomás de Alzola stood on the prow of his command searching for signs of life on the desert hills. He knew the place was inhabited by Pericú indians. But they were peaceful and kept a low profile. Pirates were his main concern.

The nabobs of the South Sea Admiralty, in their infinite wisdom, had decided to remove his cannons before he left Acapulco in April, and use them to protect the port against pirate raids. "That way you’ll have more room for cargo" they said. Now all he had to protect his ship was blunderbusses and stones.

Alzola took a deep breath. The air, though dry, was saturated with warm fragrances from the coast: mimosa, prickly pear, and sun dried coral. “I can already smell the fresh water of Aguarda Segura,” he sighed, putting a hand on his first mate’s shoulder, “and we’re not even past the cape yet.”

The arced promontory of Cabo San Lucas was a welcome sight. Awash with surf and sunlight it looked like the hand of Neptune fumbling in the shallows for errant mermaids.

He reached into his jacket pocket and took out an antique brass navigational instrument, an astrolabe that was a gift from the Archbishop of Seville, Cristóbal Rojas Sandoval, who had died the very same day that he had given it to him. Along with his spyglass, it was one of the captain’s few keepsakes.

He reached into his jacket pocket and took out an antique brass navigational instrument, an astrolabe that was a gift from the Archbishop of Seville, Cristóbal Rojas Sandoval, who had died the very same day that he had given it to him. Along with his spyglass, it was one of the captain’s few keepsakes."Another 700 miles of this wretched 9,000-mile journey to go," thought Alzola. After watering at Aguada Segura they would to reach Acapulco in ten days. He was delighted to have crossed in such good time, just four months from Manila. For the first time since setting sail, he was happy.

A turkey vulture circled overhead. The pallor of corpses yet clung to the decks. Nearly half of those who had boarded the Santa Ana in Manila Bay had perished at sea. “La muerte en el mar debe ser esperada, cotidiano incluso, solamente nunca es aceptable,” the captain often said. “Death at sea is to be expected, quotidian even, but it is never acceptable.”

Sea lions on the cape were barking. “They sound more like sea donkeys,” he laughed. Just then a sailor in the crow’s nest cried, “Vela! Vela!” Alzola raised his telescope and spotted two small ships on the horizon. “English pirates!” he cursed. “Pinche cabrón, pendejo!”

At Sampeguita, the gated community where my parents live on San Jose del Cabo Bay, every unit has a second-storey master bedroom. The old man hasn’t climbed those stairs in years, but my mother usually sleeps up there. The room has a spectacular view of the bay.

Lately, when I’ve come to visit, she’s given me this room and moved into the garage. My sister gets the same treatment. We’re spoilt, for sure, but what can we do, she insists. Besides, the garage is where she keeps her workstation and all of her bits and bobs, and it’s air conditioned.

This past week Cabo has experienced apocalyptic levels of humidity. A new air conditioner was installed in the master bedroom. No wonder I’m spending more time upstairs, sitting at the wooden writing desk, which looks like the poop deck on a Spanish galleon and has multiple hidden drawers and secret compartments.

In 2012, I wrote the first few chapters of my second novel Pirates at this desk.

Then, as now, staying focused was difficult. Sliding glass doors open onto a terra-cotta balcony with a vista that stretches across the bay, from Palmilla to Punta Gorda. Occasionally I go out for a smoke. One hit of that Acapulco Gold and I am spellbound, my face a wide open, pie-eyed target for well placed cannon shot. Mercifully, pirate ships no longer bedevil the Sea of Cortez.

I once saw a killer whale hunting in the littoral waters, a joy to watch through binoculars. But my greatest WTF moment came the morning I stepped out on the balcony to blaze and found a futuristic naval warship cruising up and down the bay, like a dark and menacing cyber-kraken from the future, the most badass ocean craft I’d ever seen.

Turned out to be USS Independence, a high-speed “littoral combat ship” from the naval base in San Diego. With her trimaran hull she specialized in operations close to shore, and had sailed into Mexican waters to provide extra security for Secretary Clinton’s visit to Cabo; she was attending the first ever meeting of the G-20’s foreign ministers, at Barceló Grand Faro, 250 yards up the beach from where my parents live.

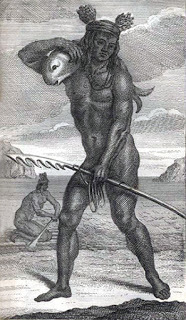

For the native Pericú indians watching from shore that November day in 1587, the kerfuffle off Cabo must have been quite the WTF moment. Three galleons flying two different colors were sizing each other up. Two ships had cannons, the other blunderbusses and stones. They hurled insults, too, at each other, in Spanish (“Pinche cabrón, pendejo! No sea gorgojos idos!”) and in English (“God’s teeth, I bite my thumb at you, you half-faced, onion-eyed, huggermugger!”).

These were not the first galleons the Pericú had seen sailing their waters. Elaborate boats helmed by elaborate boatmen had been dropping anchor off Cabo for fifty years. They came for what the Pericú called Añuiti (place full of reeds) and the Spanish Aguada Segura (safe spring), the only reliable source of fresh water within hundreds of miles.

Being one of a few tribes on the California coasts to have mastered watercraft, the Pericú were open-minded to the arrival of big boats from across the sea. But seeing them engage in hostilities was a first, indeed terrifying for those out fishing at the time.

The Spanish galleon was nearly four times the size of the two English galleons put together, yet she had no cannons to fire back at them. After one of the English ships came alongside, sailors began boarding but were quickly driven back, some into the sea. The English then pulled back, to pursue their prize with the full force of their guns, firing everything they had at her.

After the Spanish galleon began to sink the raiders again boarded, were again met with dogged resistance by her crew, but finally took control of the ship. They sailed her to a bay enclosing the mouth of the freshwater river so prized by the Spanish, where they anchored, removed the surviving crew and passengers to shore, then started pumping out seawater. They needed to keep her afloat long enough to unload her cargo.

The Pericú indians, who by then had gathered in large numbers on the beach to watch the spectacle offshore, could not have known that this single act of piracy would spell their doom.

Writing pirate yarns distracts me from the phantasmagoric image of my old man laying on his everlasting death bed. I feel guilty for not spending more time at his bedside, for not being able to do much for him, and for ignoring him.

“What’s that brownie got in it?” he asks, as chocolate crumbs tumble down his chest. He’s noticed something different in the mix. “Marijuana?”

“That’s right, dad. Remember, we talked about this. Gerry got the weed, mom paid for it, and Bobby cooked it up in a batch of chocolate brownies.”

“Oh,” he says. Later he complains of a belly ache.

“So you don’t like the brownies?” I ask.

“No,” he says, “I like the brownies. The brownies don’t like me.”

Trudging back upstairs to my cave I take refuge behind a thicket of words. It’s my very own stairway to heaven. Dad, I think, needs a stairlift.

We departed out of Plymouth on Thursday, the 21 of July, 1586, with 3 sails, to wit, the Desire, a ship of 120 tons, the Content, of 60 tons, and the Hugh Gallant, a bark of 40 tons: in which small fleet were 123 persons of all sorts, with all kind of furniture and victuals sufficient for the space of two years.”- Francis Pretty, man-at-arms on the Desire

The circumstances surrounding the sacking of the Santa Ana were serendipitous. The Manila galleon just happened to be carrying more than the usual rewards on that particular sea voyage. England was at war with Spain. And Thomas “The Navigator” Cavendish, an English privateer who had been given license by Elizabeth I to lay to waste every beslubbering Spanish outpost and galleon he found on his sea voyages, just happened to be in the neighborhood.

For six months he had been sailing up the South Sea, raiding ports, sinking ships, and burning churches in the Americas. He then heard from a Spaniard he had captured that the Santa Ana, a 700 ton galleon stripped of her cannons was sailing solo from Manila to Acupulco with a large cargo worth hundreds of thousands of pesos, and was due to arrive soon at Aguada Segura.

Cavendish knew that after a such a long sea voyage crew and passengers would be gagging for fresh water, and in no condition to resist an attack, especially without proper weapons. He must have been smiling to himself as they set sail for Cabo, swaggering on the sun bleached poop deck of his beloved Desire, gob smackingly amazed by the cunningness of own brilliant plan.

Francis Pretty, his man-at-arms, describes the bay they sailed into:

The 14 of October we fell with the Cape of St Lucar, which cape is very like the Needles at the Isle of Wight ; and within the said cape is a great bay called by the Spaniards Aguada Segura: into which bay falleth a fair fresh river, about which many Indians use to keep. We watered in the river, and lay off and on from the said Cape of St Lucar until the fourth of November, and had the winds hanging still westerly.

From my writing desk I can see the same “great bay” where the privateers dropped anchor four centuries ago. Now there’s a highway through it and piles of waterfront condos, but essentially it’s still the same desert oasis on the bay: Añuiti, Aguada Segura, San Jose del Cabo.

For three weeks they waited, foraying onto shore from time to time to barter with the Pericú for fresh water. Anything metal was of great value to them. A soup ladle fetched six barrels of water.

The natives, who had never known galleons to stay for so long, had no idea what they were up to nor did they make any trouble for them. Too busy gathering roots and shoots for the next shamanistic ritual, which they hoped would keep the danger they could smell at bay, they paid them no mind.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Without so much as a breath, Pretty recounts the events as they unfolded from the moment the Santa Ana rounded the cape:

The 4 of November the Desire and the Content, wherein were the number of Englishmen only living, beating up and down upon the headland of California, which standeth in 23 degrees and face to the northward, between seven and 8 of the clock in the morning one of the company of our Admiral, which was the trumpeter of the ship, going up into the top, espied a sail bearing in from the sea with the cape. Whereupon he cried out, with no small joy to himself and the whole company, "A sail ! a sail !" With which cheerful word the master of the ship and divers others of the company went also up into the maintop. Who, perceiving the speech to be very true, gave information unto our General of these happy news, who was no less glad than the cause required : whereupon he gave in charge presently unto the whole company to put all things in readiness. Which being performed we gave them chase some 3 or 4 hours, standing with our best advantage and working for the wind. In the afternoon we gat up unto them, giving them the broadside with our great ordnance and a volley of small shot, and presently laid the ship aboard, whereof the king of Spain was owner, which was Admiral of the South Sea, called the St Anna, and thought to be 700 tons in burthen. Now, as we were ready on their ship's side to enter her, being not past 50 or 60 men at the uttermost in our ship, we perceived that the captain of the said ship had made fights fore and after, and laid their sails close on their poop, their midship, with their forecastle, and having not one man to be seen, stood close under their fights, with lances, javelins, rapiers, and targets, and an innumerable sort of great stones, which they threw overboard upon our heads and into our ship so fast, and being so many of them, that they put us off the ship again, with the loss of 2 of our men which were slain, and with the hurting of 4 or 5. But for all this we new trimmed our sails, and fitted every.man his furniture, and gave them a fresh encounter with our great ordnance and also with our small shot, raking them through and through, to the killing and maiming of many of their men. Their captain still, like a valiant man, with his company, stood very stoutly unto his close fights, not yielding as yet. Our General, encouraging his men afresh with the whole noise of trumpets, gave them the third encounter with our great ordnance and all our small shot, to the great discomforting of our enemies, raking them through in divers places, killing and spoiling many of their men. They being thus discomforted and spoiled, and their ship being in hazard of sinking by reason of the great shot which were made, whereof some were under water, within 5 or 6 hours' fight set out a flag of truce and parleyed for mercy, desiring our General to save their lives and to take their goods, and that they would presently yield. Our General of his goodness promised them mercy, and willed them to strike their sails, and to hoise out their boat and to come aboard. Which news they were full glad to hear of, and presently struck their sails, hoised their boat out, and one of their chief merchants came aboard unto our General, and falling down upon his knees, offered to have kissed our General's feet, and craved mercy. Our General most graciously pardoned both him and the rest upon promise of their true dealing with him and his company concerning such riches as were in the ship : and sent for the captain and their pilot, who at their coming used the hke duty and reverence as the former did. The General, of his great mercy and humanity, promised their lives and good usage. The said captain and pilot presently certified the General what goods they had within board, to wit, an hundred and 22 thousand pesos of gold : and the rest of the riches that the ship was laden with, was in silks, satins, damasks, with musk and divers other merchandise, and great store of all manner of victuals, with the choice of many conserves of all sorts for to eat, and of sundry sorts of very good wines. These things being made known to the General by the aforesaid captain and pilot, they were commanded to stay aboard the Desire, and on the 6 day of November following we went into a harbour which is called by the Spaniards Aguada Segura, or Puerto Seguro.

The 4 of November the Desire and the Content, wherein were the number of Englishmen only living, beating up and down upon the headland of California, which standeth in 23 degrees and face to the northward, between seven and 8 of the clock in the morning one of the company of our Admiral, which was the trumpeter of the ship, going up into the top, espied a sail bearing in from the sea with the cape. Whereupon he cried out, with no small joy to himself and the whole company, "A sail ! a sail !" With which cheerful word the master of the ship and divers others of the company went also up into the maintop. Who, perceiving the speech to be very true, gave information unto our General of these happy news, who was no less glad than the cause required : whereupon he gave in charge presently unto the whole company to put all things in readiness. Which being performed we gave them chase some 3 or 4 hours, standing with our best advantage and working for the wind. In the afternoon we gat up unto them, giving them the broadside with our great ordnance and a volley of small shot, and presently laid the ship aboard, whereof the king of Spain was owner, which was Admiral of the South Sea, called the St Anna, and thought to be 700 tons in burthen. Now, as we were ready on their ship's side to enter her, being not past 50 or 60 men at the uttermost in our ship, we perceived that the captain of the said ship had made fights fore and after, and laid their sails close on their poop, their midship, with their forecastle, and having not one man to be seen, stood close under their fights, with lances, javelins, rapiers, and targets, and an innumerable sort of great stones, which they threw overboard upon our heads and into our ship so fast, and being so many of them, that they put us off the ship again, with the loss of 2 of our men which were slain, and with the hurting of 4 or 5. But for all this we new trimmed our sails, and fitted every.man his furniture, and gave them a fresh encounter with our great ordnance and also with our small shot, raking them through and through, to the killing and maiming of many of their men. Their captain still, like a valiant man, with his company, stood very stoutly unto his close fights, not yielding as yet. Our General, encouraging his men afresh with the whole noise of trumpets, gave them the third encounter with our great ordnance and all our small shot, to the great discomforting of our enemies, raking them through in divers places, killing and spoiling many of their men. They being thus discomforted and spoiled, and their ship being in hazard of sinking by reason of the great shot which were made, whereof some were under water, within 5 or 6 hours' fight set out a flag of truce and parleyed for mercy, desiring our General to save their lives and to take their goods, and that they would presently yield. Our General of his goodness promised them mercy, and willed them to strike their sails, and to hoise out their boat and to come aboard. Which news they were full glad to hear of, and presently struck their sails, hoised their boat out, and one of their chief merchants came aboard unto our General, and falling down upon his knees, offered to have kissed our General's feet, and craved mercy. Our General most graciously pardoned both him and the rest upon promise of their true dealing with him and his company concerning such riches as were in the ship : and sent for the captain and their pilot, who at their coming used the hke duty and reverence as the former did. The General, of his great mercy and humanity, promised their lives and good usage. The said captain and pilot presently certified the General what goods they had within board, to wit, an hundred and 22 thousand pesos of gold : and the rest of the riches that the ship was laden with, was in silks, satins, damasks, with musk and divers other merchandise, and great store of all manner of victuals, with the choice of many conserves of all sorts for to eat, and of sundry sorts of very good wines. These things being made known to the General by the aforesaid captain and pilot, they were commanded to stay aboard the Desire, and on the 6 day of November following we went into a harbour which is called by the Spaniards Aguada Segura, or Puerto Seguro. -----------------------------------------------------------------------

A fortnight passed. As a full moon rose up from the sea, every person of importance in the Pericú community was seated around the sacred fire. From atop their desert hill they had a favorable view of the valley where Añuiti flowed into the bay, and where the three ships that had been there since the half moon were now floating in moonbeams.

The light hanging over the hills behind them, against which the souls of their ancestors were silhouetted, was the color of a prickly pear. Scattered around them were the tools of the tribe: stone grinding basins, spears, lark's-head netting, and coiled basketry.

A shaman singing incantations, his face painted red with ochre, passed around a palm-bark vessel containing a liquid that had been simmering on the fire. Each person respectfully drank from it. An hour passed, taken up only by incantations. The sky was full of stars. Then the red-faced shaman climbed to the top of a sacred rock above them to call down supernatural forces.

For a moment the sky was empty. Suddenly, from the heavens above the bay came a flaming dragon that lit up the ships below with the glow of its tongue. The Pericú gasped, threw up their hands. Then came another fire demon over the bay, this one shaped like a palm tree, then more palm trees, a hefty flaming forest of palm trees. Never before had the shaman conjured up such mind-blowing sorcery. It helped that the psychoactive drugs were just kicking in. Still, WTF…

Three hundred and forty five years and a day later my father was born.

“Oh, Edmund, it's wonderful! But what about Melchy and Raleigh? You must have brought something for them as well. [Edmund clears his throat trying to think of something] - Nursie's got her beard, I've got my stick; what about the two boys?” - Queen, Blackadder II ‘The Potato’

“God bless the Queen,” roared Thomas “The Navigator” Cavendish, raising a glass to England’s sovereign of 30 years, “and long may she reign.” The Spanish captain also raised a glass, though not in triumph.

It was the night of 17 November, Coronation Day and Tomás de Alzola and a handful more people from the Santa Ana had been invited on board the Desire to celebrate with the English. It was as bizarre a situation as he had ever been in, toasting his enemy's monarch while his own king's property lay run-aground in the bay, looted of all her riches.

The English captain’s toast was the cue for the master gunner to start the fireworks display. The Desire and the Content also made their salutes by firing fireworks from their cannons. They lit up the bay with a pyrotechnic spectacle the likes of which Alzola and his men had never seen before.

“Impressive, hey?” said Cavendish putting an arm around the Spaniard who stood awestruck, his eyes fixed to the sky. “I was given a dozen barrels of water just for telling the native warlock we’d be having a firework display this evensong. Ha ha…” He then reached into his coat and produced a brass instrument, the very same one the Spanish captain had been holding when he was captured.

“An ancient astrolabe?” said Cavendish, brandishing the object so the others could see it. “Were you planning on traveling back in time?” His officers roared with laughter.

“May I have it back,” asked Alzola, reaching out. “It was a gift from…” He stopped short, knowing how Cavendish felt about Catholics. The week before The Navigator had had a friar hung by the neck from the Santa Ana’s yardarm just for making the sign of the cross.

“No, you may not,” snapped Cavendish, who then threw the object into the sea. “By the way, could I get you to sign this bill of sale for the cargo we’re purloining?”

It took the privateers two weeks to offload the Manila galleon of her most precious cargoes. For want of stowage on their own two small vessels, they were forced to leave a few things behind, much of which had already been tossed overboard into the sea.

Before departing, in an uncharacteristic show of empathy, Cavendish gave weapons, provisions, and the Santa Ana’s sails for shelter to the seafarers marooned in the bay. He then set fire to their ship. She was still ablaze when Desire and Content set a course for the Philippines, with the booty split between the two sails.

The 19 day of November aforesaid, about 3 of the clock in the afternoon, our General caused the king's ship to be set on fire, which, having to the quantity of 500 tons of goods in her, we saw burnt unto the water, and then gave them a piece of ordnance and set sail joyfully homewards towards England with a fair wind, which by this time was come about to east-north-east. And night growing near, we left the Content astern of us, which was not as yet come out of the road. And here, thinking she would have overtaken us, we lost her company and never saw her after.

Two years and fifty days after his departure from Plymouth, Thomas Cavendish sailed back into the same harbour. The Desire was only the third ship to circumnavigate the globe, after the Victoria of Ferdinand Magellan (journey completed by Juan Sebastián Elcano) and the Golden Hind of Francis Drake.

Cavendish invited Queen Elizabeth to a dinner aboard the Desire. She was suitably impressed by his haul of gold, silver, silks, ivory, spices, and porcelain. Thereafter he was knighted and joyfully celebrated across the realm. He was 28.

Although a scoundrel and a scalawag, he does deserve kudos for his audacity. In the 250 years that Manila galleons sailed the trade route between the Philippines and Mexico, no greater prize was ever looted from a “nao de China” than Cavendish's haul from the Santa Ana. Three years later he had already squandered his fortune. He died at sea at the age of 31.

By the time I was 21 I had circumnavigated the globe five times. I have my parents to thank for that fanfaronade. They took me everywhere, from continent to continent, ocean to ocean. In time, like a satellite that’s reached critical orbit, I could not be stopped. The world is a blur to me now.

At 54 I move continents on average every six and a half years. That’s a pirate’s life for me. I wouldn’t have it any other way. Can’t say the same for my parents. Retiring to Cabo twenty five years ago was meant to ensure the good times never ended, that they could both continue to enjoy their singular lifestyles up until the day they each shook off that mortal coil.

But my father is trapped in a body that will neither let him rise from his deathbed nor let him die in it. And my mother is trapped in a situation that requires more strength and presence of mind than an octogenarian can always muster. Sadly, there’s no way around it.

The saddest thing is how little my dad remembers of his own accomplishments: building 'comfort stations' in the slums of Ibadan, revitalizing the safari circuit in northern Tanzania, overhauling Air Lanka in Sri Lanka, finding a million jobs for Indonesians, and advising the Singapore government on how not to be dicks. Even the highlights are gone, no longer there to comfort him in his moment of reflection: scuba diving in the Maldives, skiing in Syria, building a waterfront dream home in San Jose del Cabo.

These days, the English and Spanish no longer visit Cabo, nor does Hillary Clinton. The Pericú indians are no longer here either. Two hundred years ago, war and disease carried over by conquistadors and missionaries, who had been sent by Spain to secure the California coast against future pirate raids, killed off the Pericú indians. Nothing of their culture and language remains.

Occasionally there’ll be a firework display in San Jose del Cabo Bay, over near Palmilla, or out in front of Barceló Grand Faro, but no one’s quite sure why. You can take a cruise aboard an authentic galleon, sail around Cabo San Lucas on a “family-friendly pirate-themed adventure” while drinking tequila and keeping a bleary eye out for whales. Yup, the pirate theme prevails, in a plethora of colourful tourist attractions. True pirates, though, are lost as sea.

Tomás de Alzola is the hero of this pirate yarn. His heroism emerges in the final chapter. For as soon as those privateers had sailed over the horizon, leaving the Spanish galleon ablaze, Alzola and his seafarers swam out to the ship and put out the fire. They then set about rebuilding her, fixing her hull, raising her sails, and setting her adrift again on the Sea of Cortez.

On 6 January 1588, seven months after leaving the Philippines, the Santa Ana limped into Acapulco, minus her cargo. On board, as well as Captain Alzola and the survivors, were two Pericú indians, husband and wife.

I have a recurring dream about my father struggling out of his bed and into his wheelchair, wheeling himself out onto the beach, and then down to the edge of the surf where a boat is waiting. He drags himself onto the boat, then pushes off and drifts out into the bay.

The sea, mirroring a billion brilliant stars under a moonless sky, is as calm as a millpond, not a ripple. Leaning over the bow he sees his reflection in the water. “There,” he whispers, “what’s that?” A league beneath the surface, glimmering in the starlight is an object resting in the sand, a brass instrument. “It’s an astrolabe,” dad says, then closes his eyes and passes away.

Published on October 14, 2016 08:01

September 30, 2016

Cortez the Killer

This morning I woke up to a strange sound, like a miniature helicopter. A black witch moth the size of a bat was thumping against my bathroom window. A window below was open but the moth had no plan B. I grabbed it and chucked it out the open window. It flew away.

Here in Mexico they call the black witch moth ‘Mariposa de la muerte’, meaning butterfly of death. If one enters a house where there is sickness, it is believed the sick person will die.

Ever since we brought dad home from hospital our house has been infested with black witch moths. Every day I rescue one, help it circumvent a closed window or a screen door. But they just keep coming back. Even now, as I write this, there’s one on the wall above my desk. From the white V mark across its wings, I know that it’s a female. She hasn’t moved since morning.

Caring for dad at home has thrown up a plethora of new challenges. There’s no pattern to his needs, and he has no sense of time. Often he’ll come up with a whole new hair brained plan about what needs to be done, in the middle of the night. Still, he’s never short of praise, thinks mom and I are consummate caregivers that should be in business together.

“Rectal cleaning service, mom and son business,” he quips, “$60 a crack. All repeat business - people need to shit every day. Discount for a month’s coverage. Market to Gringo retirees and seniors living in the South. No competition…Who the hell wants to clean assholes? No one!”

He likes his wit like he likes his martinis, dry.

It’s hopeful and heartwarming to see him laugh heartily, but those moments are the exception not the rule. My time with him is mostly spent watching him sleep or just lie there, mouth agape, staring at the ceiling. Occasionally he looks up at me, but without his glasses I’m just a blur.

What’s he thinking? Does he want to die? He hasn’t said as much lately. “I’m helpless,” he said last night, with a voice laden with confusion and remorse. “What can I do?”

“Not much.” I replied.

“Something has to happen…and I can’t do it from here.”

“What?” I asked.

“I don’t know…Do you?”

“No.”

“Can we let it happen tomorrow?” he asked.

“What?”

“Whatever…Will you come and look in on me from time to time?”

“Of course.”

It took some effort and we shopped around a bit but we’ve finally got dad the home care he needs. Ernesto, a nurse who speaks fluent English, comes to bathe him on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and Rossio, a physiotherapist, comes to help him with his muscle work on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. She’s hopeful he will eventually stand on his own two feet.

As many people have been coming to fix the air conditioning. Like my father, it’s been working on and off lately. The situation is more bearable now that the temperature in Los Cabos has dropped a few degrees. But the workmen are unreliable, say they’re coming and never show up.

Gerry knows a guy who can fix air conditioners, and thinks we need a third opinion. “You don’t have to tear up the tiles to replace those air-con pipes,” he says, with an accent that sounds like both Cheech and Chong. “You can just put a little box against the skirting like this…” He bends down and runs his hand along the crease of the wall of my father’s room. “That way they don’t have to disturb Ian.” My mother frowns at this suggestion.

Considering our failing air, there sure is a lot of thin ice in this house. Caring for the old man is stressful. Sometimes we crack. Yet despite my mother’s anxieties regarding methodology, she is highly resourceful and practical. I admire her more than I let on; she thinks I talk down to her, regard her as intellectually inferior. But I don’t. She’s proved to me time and time again that she knows things beyond my scope, that subtle intuition trumps hubris, and that she has extra sensory sleuthing powers (she missed her calling as a private detective).

She keeps both husband and home functioning, has done for six decades. Her ultimate home, here in Los Cabos, was woven from the fabric of the more than two dozen rental homes all over the world that she made cozy for us to live in. Every new city to which we got posted involved my father flying out ahead of time and finding adequate digs. A month later the rest of us would follow. My mother would then correct his poor choices and find us somewhere magical to live.

For me, home was never truly home until the shipment arrived. Therein lay my richest treasures, trapped for months on the high seas, possessions that grew more mysterious with the passage of time: Frogman Action Man and his blow-up Zodiac boat, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, and Black Sabbath LPs, and my six-inch reflector telescope.

Toys and records aside, the family keepsakes too were a comforting continuum from one place to the next, the string that held together the bead of one posting to the bead of another. Now when I visit the house in Baja I see some of those totems on the walls and shelves, juju that triggers time machines, opens portals that I easily fall into.

Cortez is an angry sea. At night its waves strike the beach with an asymmetrical beat. For days now it’s been pounding the Baja coastline with massive swells, the consequence of a hurricane passing north west of the peninsula. Today, however, it’s calm.

Sitting on the beach, gazing at the salubriously tranquil water, and rubbing my injured shoulder, I think, “I could do with the hydrotherapy.” I stand up and stride into the surfy soup. Froth lashes at my shins. The currents are stronger than I had anticipated, but I continue wading out regardless. Once I clear the small stuff, I begin swimming breaststroke. It’s so refreshing.

Suddenly a swell rises up before me, much larger than anything I’d seen from the beach. Looking over my shoulder, I can see that returning to shore is no longer an option, and ahead, I cannot swim fast enough. All at once the wave brakes, thunderously avalanching a ton of brilliant white froth towards me. I dive underwater and swim beneath the surf. It sounds like exploding ordinance, like the beach is being bombed.

After surfacing, I barely have time to catch my breath when another massive roller, larger than the last, begins to rise up before me. “This one’s a killer,” I whisper. Hyperventilating to give myself more time underwater, I wait until the very last moment. On the face of it, time appears to stand still. Three pelicans skim across the crest of the wave, hunting for fish trapped in its pellucid sea wall. I dive under, and just in the nick of time, taking the brunt of force on my legs.

Resurfacing, I now fear for my life. The period between waves is insufficient to recover. Another comes at me, and then another, every time a bigger one. And I dive under them all, swimming longer and farther each time. Finally I get beyond the swell, and there are no more waves on my horizon. But I am some three hundred yards from shore and drained of all my might.

Under an azure sky, treading water just enough to keep my chin above the sea’s deceptively calm undulations, I think of Neil Young’s ‘Cortez the Killer’. “He came dancing across the water / With his galleons and guns / Looking for the new world / In that palace in the sun.” The song is about Hernán Cortés, a conquistador who conquered the Aztecs and colonized Mexico for the Spanish, and the eponym of this sea on which I am floating.

With a slow butterfly stroke, or moth stroke, I carefully swim back to shore, occasionally looking over my shoulder to see what might be coming up behind me. Sure enough a whole new set of waves is on my tail. Swimming side-stroke now, with an eye on the breakers, I take a chance on riding them. Every wave, as mighty as it seems, simply picks me up and gently plants me closer to the shore, before breaking just beyond me. I can’t believe my luck. In due course, and much to the surprise of the Mexicans who have been watching me all along, I step out of the surf and calmly walk back up onto the beach.

Dad is sitting on the porch in his rocking chair, comfortably surveying the view. Rossio, his physio, got him to stand momentarily while she shifted him from his wheelchair to the rocking chair. Progress! Soon he’ll be back on the dry martinis as well.

Looking around I notice something is missing. The black witch moths have all gone.

Published on September 30, 2016 12:32

September 13, 2016

The Old Man Staring At The Sea

“Old age is like a plane flying through a storm.

Once you're aboard, there's nothing you can do.”

- Golda Meir

My dad’s eyes twinkle, a glimmer of triumph spreads across his grey bristly face. He has just had a sip of Scotch whiskey, his first in six weeks. My mother and I smuggled it into his ward at the Clinica San Jose. Seems to have done the trick.

For a while there he thought he was in Singapore, in our old apartment on Mount Elizabeth Drive, and that our Scottish neighbors the Reeves were having a party upstairs.

“It’s a storm, dad,” I tell him.

“Did you say storm?” he asks. I nod. “Oh Christ!” he moans.

“Lets spare him the details,” my mother says quietly. Hurricane Newton, with wind speeds of up to 95 miles an hour, is due to make landfall in Los Cabos during the early hours of the morning. “You’ll be safe here,” she says, propping up dad with extra pillows.

She has spent countless hours since he was hospitalized propping up his pillows, and at times thinking about putting one over his face. Now she would rather he was infirm at home, with all the challenges that entails, than confused and alone in this hospital room, staring at the walls. “At home he can stare at the sea.”

Yesterday I bathed him. Getting an uncooperative octogenarian into the shower, even with a rolling commode chair and my gorilla tracking skills, was no easy task. The ordeal seriously tested my commitment to be his caregiver.

Earlier this evening his doctor dropped by, having been away for a week in Mexico City. “He is strong,” he said, “my best patient.” He agrees that the old man should return home soon. “But not until the day after tomorrow, because things will surely be chaotic after this hurricane.”

Six weeks ago when I got the call I was thousands of miles away on the Kenya coast. My mother phoned to tell me my father had suffered a stroke and a bout of infections, and was critically ill in hospital. His doctor didn’t think he’d make it through that night.

Unable change my air ticket, dazed and confused by the distance and not knowing his condition from one day to the next, I was sure I’d never see my dad again. How does one prepare for the death of a loved one?

I took comfort in knowing that earlier this year he and my mother had visited me in Kenya, a journey halfway round the world that others thought they were mad to make. Returning to the country where they first expatriated 50 years ago, the fountainhead of all our peripatetic lives, completed a circle for me if not my parents. They stayed for six weeks.

When I finally reached his bedside, I was surprised by how healthy he looked. His breathing was labored and he was suffering from a bundle of aches and pains, but as far as I could see there was not much else wrong with him.

These days he’s more compos mantis, if not always sure of his whereabouts. And because he is one of only two patients, both of whom are men, in a maternity hospital run by nurses and nuns, he is going a bit stir crazy.

A nurse steps into the room, says in Spanish that the rain has started to fall quite heavily and whomever is going home should probably do so now. My mother promptly leaves.

Presently it’s just me and my dad in the hospital ward, listening to Ella Fitzgerald, Artie Shaw, and Frank Sinatra, a few of his favorites. “It’s not unpleasant,” he says, drifting off to sleep.

My father, my captain, architect of my life, how could I not care for you in your dotage? I am a creature of your design, the product of a lifetime spent moving from one Third World posting to another. For better or worse, you made me the Third Culture vulture I am today. I owe you.

Things are starting to go bump in the night. While my father sleeps soundly, I worry about my mother all alone in her home.

Home is a boutique, beach-front villa on an estate called Sampaguita, one of fourteen semi-detached, two-storey units shaped into a horseshoe around a palm-shaded desert scape with a pool and jacuzzi. For all it claims to be a “secure gated community”, my parents’ home abuts a beach-front wall that’s barely a meter high.

Despite the fearsome clangor outside, the Sea of Cortez rising up to reclaim its shoreline, I lay down on the cot next to my father’s hospital bed and fall into a deep sleep.

It’s 8:30 am and he’s still sleeping. I step outside to observe mother nature in action.

Since day break the wind has died down a bit, though gale-force gusts still batter the barrios. Tin roofs and door frames rattle, and palm trees oscillate like VU metres in a Thrash metal studio. Still, from where I am standing, on the front steps of the clinic, the damage does not look too bad. But where is mom? The networks are down.

Back in the ward, my dad is awake. “I need to get out of the market,” he says. “I made a big mistake, fell asleep after it dropped. I may have lost over $10,000, which was a lot money back then, though not for the big players.” He’s lost in time and space.

My dad has dementia, a persistent disorder of the mental processes marked by memory disorders, personality changes, and impaired reasoning. Gorillas, those hairy mountain cousins I've dedicated a lifelong career to saving, don’t suffer from dementia, even though they share 97 percent of our genetic makeup. Research into the great ape genome has revealed that the gene which causes dementia is common in gorillas but does not cause them ill-health. When they discover why, it will probably be too late for my dad.

“Is the hurricane still blowing?” he asks. Alas, he’s back in the moment.

“Gusty but not so bad,” I reply. “Doesn’t seem to have done much damage.”

“Christ, I hope not,” he sighs. Two years ago Hurricane Odile devastated the Baja peninsula. In the aftermath there was no water, no electricity, and many hundreds of Gringos had to be evacuated, he and my mother included.

My mother steps into the room. “Damn, am I glad to see you,” I sigh. “How’s the house?”

“Flooded,” she smiles. “I’ve spent the last hour mopping up. Still, it could have been worse. At least the electricity’s back on. How’s he been?”

“Slept soundly through most of the night.”

Leaving my dad in his hospital bed, we drive home. Not many vehicles are out on the roads. Although nothing major has been toppled by the hurricane, the town looks like it’s been dunked in the sea a few times. The streets are littered with palm fronds, highway signs, cacti, and a few fallen palm trees, and none of the stop lights work. Meantime the downpour continues unabated.

Closer to the beach the streets are cluttered with a lot more detritus, and everything is coated in drifts of wet sand and mud. At the entrance to Sampaguita, my mother taps in the entry code. The gates open slowly, jerkingly, grinding against a sand encrusted mechanism.

Outside the house is coated with sand and inside flooded with seawater. After a slap-up breakfast of fried eggs, bacon, and toast, we begin a marathon mop up. Then the electricity cuts out. Now we’re trapped on an estate where the electrically-powered security gates no longer function. The only solution is beer. I drink half a dozen before tackling the sand caked patio, shoveling it up bit by bit with a dust pan. Late in the afternoon the power kicks back in.

Remarkably by nightfall, while storm swells continue to pound the beach, the sky is almost clear. My mother and I sit on the patio, drink Don Pedro brandy, and watch Mars and a half Moon descend beneath the arches. The coastline is unevenly lighted. Many homes have yet to see their power return. We are the lucky ones.

She tells me how after Hurricane Odile she got the barbecue going and cooked up all the fish, beef, pork, and chicken she had in her freezer. “There was no electricity, so it was all going to go to waste anyway. So I cooked, and Gerry distributed the food to the local community. It went down well.” (Gerry’s good people, brought me some weed today without me even asking.)

My mother is sitting at the dining room table, sifting through bits of paper. “I wish your father had half a brain,” she says, grimacing at the pile of paperwork, “so he could help me understand what some of these things are for.” Overwhelmed by the full magnitude of managing both of their affairs, she is prone to panic at times.

My sister and her husband are helping her sort it all out. After my father fell ill, they made staggered visits to Cabo to offer their support. My brother came too, despite a flight cancellation that reduced his visit to less than two days. They’ve all since returned to Canada. I arrived late but I’m here for six weeks, until my mother’s 81st birthday.

She’s quite dynamic for her age. I cannot believe how much energy she has. Half the time she can’t find what she’s looking for because she put it somewhere unknown to her now. Consequently, she’s kept busy by an endless treasure hunt of her own making. She is also a control freak. It’s not enough to try and help her, if you don’t do it her way you’re not helping at all.

And yet, we've always been close. I was her willing accomplice when she searched for Yoruba wood carvers in the backstreets of Ibadan, or master painters in Colombo. And she was my mine when, with just three months left in my senior year, I got expelled from boarding school in Fort Dauphin, Madagascar, for smoking marijuana. She subsequently convinced the faculty to allow me to graduate, which they agreed to only if I lived off campus with her.

Dad is home from hospital. We parked his wheelchair out on the patio then let him stare at the Sea of Cortez. Maybe now that he's back home, in the comfortable surroundings that he worked so hard to acquire, he'll find pause to die peacefully. His quality of life only gets progressively worse. I think it would be a blessing if he passed sooner rather than later. I am not comfortable about praying for my old man’s death, but there you have it…

It’s four days later, and he’s staring at the same scene. “Take me back to bed,” he moans.

“Already?” I ask. The strain of lifting him in and out of his wheelchair is starting to take its toll. “But you’ve barely been up ten minutes.”

“I want to go back to bed.”

“I only got you out here because you asked me what the hell you were doing in bed at ten to twelve. Now you want to go back in again..? Okay, no problema.”

I’d be lying if I said me and my old man don’t still got beef. Nothing I ever did warranted his admiration. He couldn't find it in himself to forgive me for getting expelled from boarding school, spiriting his wife away to some godforsaken island for 3 months, all because of pot. Consequently, we were at loggerheads when I needed him most. Pooh-poohing my ambition to be a writer (not cool), he railroaded me into engineering instead. In due course, I dropped out of three universities.

“Three strokes and you’re out,” he says, lying in bed in the adumbrated light of his bedroom. “I’ve already had two, so one more and I’m gone.” He’s surprisingly lucid, waxing lyrical on the subject of his impending death. It’s official, at 5pm today he says he’s going to pass. “An hour earlier and you get minus points. An hour later and you get plus points.”

He wants to know that the booze he bought - a bottle of Black Label, bottle of gin, bottle of vodka, and the brand of beer that Peter Hatton likes (Modello) - is in the fridge. He expects a bibulous wake. He never bought nothing.

“Are we in Singapore, Thailand, or where?” he asks.

“Mexico,” I say.

“Mexico? How…” He stares into the nothingness for a moment, searching for the portal which opens the corresponding memory. “Los Cabos?”

“That’s right.” I turn up the music on my Beats Pill, a silky smooth crooning diva of the Golden Age who's seducing the spirits. “Who’s this we’re listening to, dad?”

He concentrates on the music, closes his eyes for a bit. “Sarah Vaughan,” he says. I nod satisfactorily, then wonder.

Last night he almost turned down a glass of Black Label. The effort needed for twisting his wrist and tilting back his head was just too great. He shook his head in despair. We wondered if this was it… But in the end he used a straw to finish his whiskey.

Keep on keeping on, mzee.

Published on September 13, 2016 22:12

November 30, 2015

Loving The Repat

“Now I'm going back to Canada / On a journey through the past / And I won't be back till February comes / I will stay with you if you'll stay with me.” - Neil Young, Journey Through The Past

“Just chill, uncle,” says Liam. “You’ve done so much with your life already.”

It is after midnight and, too drunk to drive, we are slumped in the back seat of a Tesla electric car hired from Uber, an online taxi service. The ride across town is smooth and hushed, and the abundant window space provides us with dramatic views of the streets.

“I know I haven’t been much of an inspiration lately,” I say, slurring my words, “moping around the house in my pajamas, smoking blunts, listening to tunes with the volume cranked up…”

He puts a hand on my shoulder then smiles. “You’re always an inspiration to me, uncle.”

I am blessed. After decades of wandering aimlessly in a cloud, I have returned home to a mother lode of kindred hospitality. My sister Andrea and her husband Dara have given me work, and their son Liam has put a roof over my head. How can I ever repay them?

The Tesla drops us off at a club in The Glebe. Inside, Liam bumps into an attractive young woman who, it turns out, once had a crush on him in high school. “I’m on a Tinder date with another guy,” she says, “but I’ll come over and dance with you later.” That never happens. The next morning he fervently scans Facebook, looking through friends of his school friends, in a vane effort to try and spot among the multitude of profiles the pretty face he saw in The Glebe last night.

Charge your glasses, I am now the proud owner of a Purple Card, consequently a fully fledged repat. All that remains is for me to fill out a stack of forms and wait in line at a bunch of government offices…The immigration lawyer did warn me that life would have to get a lot more boring before it got exciting again. Jet-setting is anathema to customs officers. Put simply, I need to repatriate gracefully.

I never intended to repatriate. I know from experience the locals think “repats" are off-topic. That thousand yard stare is fixed on shit way beyond their comfort zones, and they do not want to hear about it. “The fuck cares that you’ve been anywhere?”

A repat is the opposite of a refugee. Canadians love refugees. Our new prime minister promised to take in 25,000 Syrian refugees by the end of the year. After the recent attacks in Paris, however, that number got reduced to 10,000, of which most will be privately sponsored. Still, following a more rigorous screening, the remaining 15,000 are due by the end of March.

The talk in my sister’s house is about taking in even more. Neither she nor Dara, her husband, believe refugees pose a serious threat as potential agents of jihad, nor do they care that when the time comes many will not want to repatriate. Just throw open the damn doors, they say.

As a self-made man of Irish origins, Dara fully appreciates what the chance of a new life in a new world can mean to someone. Last week on Facebook he posted this:

“Mums, dads, kids, friends, brothers, sisters, aunties and uncles - all welcome to come to my Canada from any refugee place on earth. If you are suffering or fleeing the horrors of wars or such you are very very welcome here at my dinner table.”

Christmas decorations are going up early in our house, a reflection of the residents’ good cheer. Eric is stringing lights up on the front porch. Erin, his girlfriend, is standing by the door watching. Liam’s tenants, a handsome couple in their late twenties, have been remarkably obliging about uncle gorilla man living in their basement, rent-free.

“Do you hate Christmas?” Erin asks me, scrunching up her elfin features. It seems an odd question to ask. Perhaps she wrongly detects an attitude in me. “Au contraire,” I say, “I fucking love Christmas. The tinsel may go up late in Africa but it stays up until March.”

The house on Bell Street seems an unusually large residence for unmarried hipsters. But my housemates are exemplary of Canada’s bright future. Ambitious, driven, with decent jobs and cars, they work hard, go to bed early during the week, and play hard on the weekend.

Pastimes revolve around the large TV screen in the living room: watching series and movies on Netflix, YouTube fail videos of people harming themselves, and Super Mario Racing, a game Liam and Eric seem to have mastered.

I see in them an alternative life-path for myself, how I might have turned out had I stayed put. And they have helped me dispel a few misconceptions about my fellow countrymen. Turns out they are not all outdoorsy, passive aggressive, browbeating social engineers. Some could actually care less if their neighbor has the music up too loud, lets the dog off its leash, or drives around without wearing a seatbelt. Live and let live, they say.

Lately I have been listening to a lot of Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, eating poutine, and drinking craft beer, but I have yet to find my inner Canuck. I am certainly not built for this weather.

We live close to the action. Little Italy, a hub of trendy restaurants and bars, is just a short walk away, or the time it takes to listen to Led Zeppelin’s Stairway To Heaven. At the end of the day, if it is not too cold out, I like to wander over for a relaxing beverage.

Wrapped up against the elements, I skulk past my neighbors’ doorsteps. Even in icy conditions they gather outside on their porches to smoke. Brrr! A wolf, or a coyote, or even a ‘coywolf' would be less out of place. I am a leopard, uneasy in a tropical town, maybe, but completely at ease in jungles and savannas. Here in the Great White North, however, I stand out a mile.

It is too early for regulars at the Moon Room. The music is up loud but the bar stools remain empty. Like a mine shaft, the only source of light is a dozen mason jars laid out around the bar with candles inside. Stare at one long enough and the rest of the place fades to black.

Moon Room has hit on a winning formula: bijou, intimate, and quirky, with high standards and a visible pride among its staff. The bar is known for its all-female cocktail bartenders who also prepare the food, an eclectic menu of expensive but funky bar snacks. Watching young women prepare ‘Sexy Grilled Cheese’ in front of me as I drink my St Amboise beer is more than a thrill.

As a third culture vulture I came home to scavenge my heritage, and can serve no other purpose except to add a bit of contrast to the local color. Maybe my purpose is to be a guiding light.

Liam is a man with many solutions and few problems. Charming, smart, and with an upbeat disposition, he has what it takes to get by in life. At work he is a star, racking up mountains of cash for his employers. They call him the wizard. “Give it to the wizard, he’ll know what to do.”

He insists that the abundant hospitality he has shown me since my homecoming in September is simply good karma for when I welcomed him into my home in London ten years ago.

I have mellowed in the intervening years. Dug in deep in Uganda, hammering out the dents in my soul, I found a more sympathetic voice for inward dialogue, and stopped beating myself up about my mistakes. The conversation continues.

He and I share an impulsive gene. We can change directions on a dime. So far his horizons have been limited. I aim to change that. As a global nomad my legacy is simple yet intangible: an atlas of unrelated events, places, and people. For all I have tried to write about this journey, it has to be seen to be believed. I want my nephew to get a taste of that world.

Malindi on the Kenyan coast, where the wind cries, “Salaama”, is a good place to start. Aesthetically pleasing in the Moorish tradition, uncluttered and ancient - Vasco de Gama stayed for a fortnight in 1498 - the town is one of East Africa’s best kept secrets. A dose of whispering palms, coral cliffs, and dhows catching the trade winds on the up tide should cure all that ails him. I spent six weeks there last summer, in an ocean-front villa belonging to a good friend of mine, and did not want to ever leave.

The wind and the surf are quarreling. A coconut falls, tries to settle the argument. Then, one by one, from a large overhanging tree thick with wandering branches, a troop of Sykes monkeys descends onto the roof and begins foraging for windfall on the terra-cotta shingles.

The sound awakens you. With one eye half-opened you see the tropical sunrise. You are lying in a four poster bed in the centre of a second storey bedroom sparsely decorated with antique wooden furniture, and surrounded by levered glass doors. They’re all open, allowing the fragrance of seaweed, salt water, and frangipani to waft in to your room.

Without leaving your bed, you part the mosquito netting to gaze upon a broad swathe of ocean, sapphire in the distance and mottled emerald and turquoise over the reef. A string of white-capped breakers stretches from horizon to horizon. Six dhows are sailing past, their progress marked by a grove of crooked palms on your property. You can see they’re moving fast, helped on by a brisk morning northerly. At this point you may struggle to recall how you came to be sleeping in a paradisiacal villa on the Swahili coast. Maybe this is a dream…

Published on November 30, 2015 21:04

November 13, 2015

Man Without Country

“Hey uncle,” says Liam. “Hey nephew,” I reply. We press knuckles. Reunited after many years apart, uncle and nephew are seated by a roaring campfire next to a pond in a forest. It is not quite the wilderness, only an hour and a half drive north of Ottawa, but refreshing and inspiring.

We are not alone. Thirty to forty others have gathered for Mocktoberfest, a weekend festival of live music and unlimited beer drinking. It is the dream-child of MaYo and his band of merry carpenters. They have erected a hamlet in the forest, a hodgepodge of tree houses and living pods strung together by ladders and wooden walkways. Basically, it is camp for grown ups.

For me, recently arrived from Kenya, it is a rare opportunity to observe the locals up close, jot down a few notes. “They drink like Africans,” I write.

Liam sees me scribbling in my notebook, then says, with a goofy voice, “Dear World, this is my story. I hope you like it…” He never fails to make me laugh and is not afraid to take the piss out of me. We are wired the same way.

Spending time with kith and kin is good for the psyche and helps me adjust. My sister Andrea and her family have opened their hearts and homes to me. Nephew Liam has given me a place to live. Brother-in-law Dara, always an enabler, is helping me trawl through the paperwork. And Andrea’s cooking and knitting keeps me fat and warm. Bless them.

“Why is it,” I ask Liam, “that in every other country I’m like a chameleon, blending in nicely with the locals, but back here, no matter how hard I try, I stand out?”

“They know, man,” says Liam, “they can smell an outsider.”

“Right,” I say, taking a sip of reposado tequila. “Watch how quickly the crowd becomes a mob when the outsider refuses to conform.”

“What the fuck you talking about, uncle. These people think you’re way cool.”

“I don’t mean these people. These are good people, my kind of people. Any one who enjoys psychoactive drugs is alright by me. I’m talking about regular Canadian folk.”

O Canada, my home and native land… Viewed from afar in the 1970s, your freedoms, tolerance, and uniquely progressive leader, Pierre Trudeau, looked mighty appealing to me. Growing up overseas, all I ever dreamed about was my next homecoming.

I was born in Montreal, started out life in a two storey cedar-paneled riverside home on Green Island that once featured in Better Homes and Gardens, the kind of suburban utopia that people in far off dusty lands dream about. Then in 1967 my family expatriated to Kenya.

While we were away, the radically francophone Parti Québécois rose to power in Quebec. After Bill 101 got introduced, defining French as the only official language, Mom and Dad decided to sell the house on ‘Île Verte' and transfer our home base to Ottawa, in anglophone Ontario.

My first summer here was in 1978. I was planning to repatriate then, attend Woodroffe High School, and live in my parents’ new high-rise condominium. But as the summer wore on and I began to discover Ottawa on my bike, my outlook changed. I decided to return to the Tropics.

Over the next two years I would be arrested in The Seychelles, get expelled from boarding school in Madagascar, go on safari in Tanzania, learn to dive with Arthur C. Clarke in Sri Lanka, celebrate my eighteenth birthday in Malaysia, have my appendix removed in Singapore, and barge up the River Thames to Oxford with the lovely Caroline Bull, object of my unrequited love.

When I did finally repatriate in 1980, Trudeau was still prime minister, re-elected after a brief hiatus, but I failed to fit in. To regular folk I was little more than an exotic freak. Strange talk of peculiar customs in distant lands caused them to roll their eyes and sneer.

Thanks to binge drinking and substance abuse, I did eventually find some common ground. And I could dance. But all I ever dreamed about was getting the fuck out. After Trudeau left office and I dropped out of university for a third time, I got my chance. But that’s another story.

Leaping ahead 30 years, due to circumstances beyond my control, I am again repatriating. Not much has changed. As before, a Trudeau is in charge; Justin, son of the late Pierre, was elected prime minister shortly after I returned. And I am still an exotic freak.

“When was the last time you filed a tax return?” asks Dara. He is treating me to lunch in Rockin’ Johnny’s Diner in Westgate Mall.

“One thing at a time, man,” I laugh. “First I need to find a job.”

“You’re a man of many talents,” he says, with a hint of old country in his accent. “I’m sure you’ll find something.”

“I’m not holding out too much hope,” I sigh. “As a fundraiser I raised over $10 million for good causes. That’s a wealth of experience you’d think was worth tapping, And yet I haven’t had a single goddamn reply to the dozens of applications I sent out for fundraising positions.”

“Why do you think that is?”

“Probably because I don’t have a bachelors degree,” I say, tucking into my bacon Swiss burger. “Apparently, decades at the industry’s cutting edge doesn’t make up for dropping out of college.”

“Don’t give up on that front,” smiles Dara. He is nothing if not quietly tenacious.

Another option is to look for bar work. I have got mad mixology skills, cut my teeth as a bartender in London’s wild West End. Not so straightforward. They told me I would first have to earn a Smart Serve qualification; Ontario’s weird liquor laws require special knowledge. That I did, leaned a few things along the way. But no one wants to hire a smooth-talking bar steward in his mid fifties who lacks the proper paperwork.

So I applied for an Ontario Photo Card, also known as a purple card. Having never learned to drive (yes, that’s right) I do not have a driver’s license, ergo no second form of photo ID. The purple card will allow me to get the citizenship certificate that I need to get the social insurance number that I need to be allowed to work here. After that it is all uphill.

Part of me just wants to get the fuck out of Dodge and go back to doing what I know best. Plan B is a business proposal for a backpacker’s hostel in Malindi, Kenya. I’ve been trying to draw others into the scheme. Who wouldn’t want to live on a paradisiacal ocean-front villa, eat paw paw and mango for breakfast, wet their toes in the Indian Ocean? Slaves to the treadmill, that’s who. Africa’s not for sissies. Anyway, Plan B would just put me right back where I started.

Along the vacant tree-lined shore of Dow’s Lake, dead leaves cover the ground, stark boughs and branches claw at an overcast sky, and a chill wind encircles me: the ghosts of my ancestors. They are questioning the choices I made that led to this awkward situation: man without country. Never before have the consequences been so apparent to me.

Still, it has been a fun ride, seeking out adventure, living life imaginatively, and moving continents every six years or so. There is a movie of it in my head that I play over and over. None of it makes any sense but at least there aren’t too many scenes where I am unhappy. I have few regrets. One planet, one life - no rehearsal.

Repatriating, regularizing my citizenship status, trying to find work in Canada as an unskilled, middle-aged, third culture dropout: these are all big challenges. Over the next few months I will be blogging about my experiences of trying to fit in. I hope my insights help other people like me.

Who am I kidding, there are no other people like me.

Published on November 13, 2015 13:30

October 31, 2014

Passion & Creativity in Wakaliwood, Uganda - Ramon Film Productions

Published on October 31, 2014 07:51

October 16, 2014

Resurfacing

It’s a scorching, dry Saturday morning in California. Another rainless summer has turned the hills above San Leandro yellowish-gray. My taxi turns off a serpentine drive into an empty parking lot.

It’s a scorching, dry Saturday morning in California. Another rainless summer has turned the hills above San Leandro yellowish-gray. My taxi turns off a serpentine drive into an empty parking lot.Embedded in the hillside, the Alameda Juvenile Justice Center is a vast, rectangular three-story construction, built with beige cinder blocks that blend in well with its surroundings. There’s no one in sight.

After instructing my taxi driver to return in 90 minutes, I activate the intercom next to the weekend entrance. “Who is it?” asks a female voice.

“Greg Cummings. I’m the author giving a talk to Unit 4 today.”

“Who?”

“Greg Cummings. Amy Cheney arranged my visit…”

“Hang on a minute hun.”

While I wait for clearance into the prison, Mountain Mike’s escape story comes to mind.

When Mountain Mike escaped a minimum-security federal correctional facility called William Head on Vancouver Island, he fashioned a raft from a coffin used in the prison’s amateur theatre production of Dracula, then paddled out across the Juan de Fuca Straits towards the Canadian mainland.

The coffin disintegrated and Mike sank to the bottom of the cold straights. “I was sure I was a goner,” he recalled, “but a divine light beaconed me upward again. And then I found the strength to resurface and swim ashore.” He had a couple of weeks of freedom before the Mounties caught up with him.

I heard about Mountain Mike from one of his fellow inmates. It was October 1983, and I had just watched a performance of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by William Head on Stage (WHoS), an inmate-run prison theatre company – the only one in Canada that invites the public into the prison to see their shows. I was struck by the force of the cast’s performances, playing to a packed house, unbound by their incarceration. I had never seen such savage intensity in the eyes of actors.

____________

Amy Cheney and I connected by chance, in July 2013, while I was googling mentions of my novel. In a piece titled ‘On the Shelf with Amy Cheney’ that was posted on the Children’s Book Review blog, Cheney is asked which books are most frequently checked out of her library. “Right now it’s War Brothers by Sharon McKay—anything about child soldiers my kids can relate to. Gorillaland by Greg Cummings is also doing well. Everyone has read Coe Booth, Simone Elkeles, Alexander Gordon Smith and Ishmael Beah. Action, relevance and overall great stuff.”

Her love of literature, and a tearaway nature led her to a career in the California correctional system, turning young minds on to books. “One of my students who never read before said when she heard me talk about books it sounded like candy, and she wanted some.”

Her love of literature, and a tearaway nature led her to a career in the California correctional system, turning young minds on to books. “One of my students who never read before said when she heard me talk about books it sounded like candy, and she wanted some.”Yesterday, pushing a cartload of my novels through the corridors of the Juvenile Hall, zig-zagging between cell units and the library, she seemed protected by a forcefield of persuasive intent, like a Jedi knight.

I was supposed to arrive in time to give three talks on Friday, but a mega-storm over Texas delayed my appearance by twelve hours, so I was only able to give one. Hence a second visit has been arranged. It being a Saturday, I’m now flying solo.

Every door has a buzzer and an overhead camera. I press the button. After a moment the door unlocks and I’m able to turn the handle. I pass through several empty rooms and corridors, repeating the process again and again. The final door slides open on its own. A guard in a darkened control room peers through the reinforced glass at the contents of my rucksack, takes my Canadian passport via a drawer in the wall, and then asks me to sign the register. I’m in.

Notwithstanding the two nights I spent locked up in British holding cells – for separate offenses – and the previous afternoon, this is my first time entering a correctional facility since One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

In the belly of the facility six windowless units house dozens of young offenders whose ages range from nine to seventeen. Most are serving long sentences. They’re all locked up when I enter Unit 4, a sky-lit two-story common room surrounded on two levels by cells. I introduce myself to a woman in uniform seated behind a raised console. She smiles, shakes my hand. She is expecting me and directs me to an adjacent classroom.

With a mix of anxiety and enthusiasm, I scan the colorful displays pinned to the classroom walls. The vibe is encouraging without being too condescending. Then, one by one, a coterie of teenage boys saunters in, comprising a range of heights, builds, ethnicities, and attitudes. Each one introduces himself, shakes my hand, then finds a seat. It’s like an episode of Welcome Back, Kotter.

“I’m here to talk about gorillas,” I holler, hoping the resonance of my voice will calm the room. “The band or the ape?” asks a round-faced Latino kid. He is a picture of candidness. On the faces of the others I see genuine interest, though many appear ambivalent, and a couple have only come to socialize. “The ape,” I smile.

During a gorilla slide show, I tell them how a silverback gets his name, the politics of gorilla groups, and their similarity to humans – that we share 97 per cent of our genetic makeup with gorillas. A wiry black kid at the back of the classroom raises his hand. “Is it true that you can get a blood transfusion from a gorilla and survive?”

“Good question,” I reply, surprised by his grasp of the subject. “Yes, you could potentially survive one transfusion from a great ape, providing the blood type matched.”

I do my impression of a charging silverback. Starting from a squat position, I utter a series of hoot sounds, rapidly slapping my chest in quick succession, and with a loud bark I leap forward, to uproarious laughter from the kids. “And what do you do if a silverback charges?” I ask, catching my breath.

“Bounce! Bail ass out of there…”

“No. If you run you are sure to die. You must stand perfectly still and act submissively, avoiding all eye contact with the charging silverback.” Incredulous laughter.

I read a chapter of Gorillaland, the story of Dieudonné, a child soldier who, after years in the service of the rebel warlord General Cosmo Zomba wa Zomba, is forced to witness the execution of his parents. In the aftermath of an earthquake he takes flight with the general’s diamonds, his heart set on freedom, and runs all the way to Uganda, only to have it all tragically end in the jaws of two hungry lions.

“Aw what? No way! The kid gets eaten by lions? What happened to the diamonds?”

But my hour is up. As they leave the classroom some of the kids give me a ‘bro hug’ and thank me warmly. I am touched.

Life is about choices and prospects. Young people make mistakes and face tough challenges as they try to revive their prospects in life. It’s the same for every one, whether or not you are imprisoned for your mistakes.

The difference with inmates is that they are given few choices after incarceration. Punishment is king. This absence of volition is an obstacle to inspiring them. On the other hand, they are a captive audience. Turn these young minds on and I know they will read my novels, and maybe one day write their own.

____________

Come Spring 1984, five months after I saw One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, I was working for Stage II, a theatre group established for, and by, ex-offenders, after their release from William Head. We were staging One For The Road, Harold Pinter’s bleak one-act play set in a prison in a fictitious totalitarian country, which had premiered in London and New York in the two months previous. Ours was the world’s first amateur production, and the company was excited about blazing such a trail in stagecraft.

Stage II faced unique challenges, like keeping the actors in one place. A month before opening night one of our principles went AWOL, hitting the road for greater freedom, and in total violation of his parole. No one in the company harbored any ill will towards the guy. He did what he had to do. We found someone to replace him and hoped the new guy would last. He stole the show.

Working in the theatre with ex-offenders I watched men struggle to temper their emotional intensity through artistic expression. Often the roles were reversed: the tenderhearted newspaper salesman on stage was once an armed robber. Having the freedom to express oneself is not the same as freedom itself.

In the eyes of the young men that came to hear me talk at the Alameda Juvenile Justice Center I saw souls that were drowning. I think I understand. I hope my talk and reading, a career milestone, provided some resuscitation, however briefly.

-----------------

Also posted on Reaching Reluctant Readers

Published on October 16, 2014 16:39

October 15, 2014

Gorillaland - Chapter Three