Greg Cummings's Blog

November 20, 2023

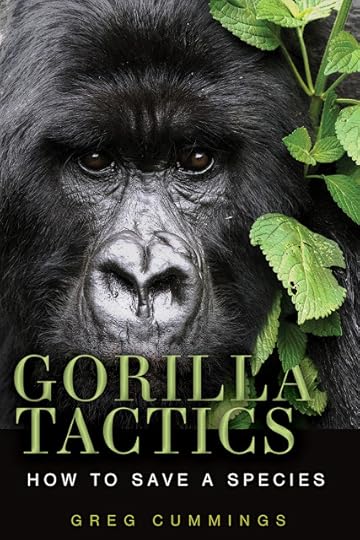

Gorilla Tactics: How to Save a Species

November 10, 2022

A Hidden Battlefield

Trumpeting Dixie on their musical horns, a parade of vintage Italian compacts cars drove down Corso Umberto I in Leonforte. People scrambled to the sidewalk to avoid the fun-sized motorcade. My wife and I were surprised to find the town bustling with so many people on the first Sunday of October. Its cobblestone streets were lined with food stalls. Billows of smoke brightened by the morning sunshine rose from sizzling grills and infused the brisk autumn air with intoxicating aromas. We had stumbled on the Sagra della Pesca, an annual food fair. Celebrating their recent harvest, farmers had come from far and wide to display the region’s cornucopia of delicacies — cured meat, wine and cheese — and each one had to be sampled. A busking teenager played an upbeat tarantella on his accordion. “Isn’t that from ‘The Godfather’?” I asked.

“No,” said Roberta, “that’s ‘C'è la luna mezzo mare’, a traditional Sicilian song.” She sampled a local cheese and smacked her lips. “They have all the ingredients we need for a fantastic picnic,” she said. Being Sicilian, and my wife, she knew what to choose.

Sagra della Pesca

Sagra della Pesca“Looking around at today’s lively, kid-friendly harvest fest,” I said, as I bit into a slice of capocollo dolce, a salami that a vendor with a weather-beaten face had offered me, “it’s hard to reconcile what happened here 80 years ago.” Evidence of the violence was all but gone, buried deep below cobblestones and hidden behind walls, but Leonforte was once the site of a fierce World War II battle between invading Canadian forces and defending German and Italian forces.

I am Canadian and Roberta and I live on Vancouver Island. Since marrying five years ago, she and I have visited Sicily on four occasions together. Based in Messina, her hometown, we usually stay for a month so she can take care of her aging parents, restore familial ties, and look up old friends. Each time, we explore somewhere new. My interest in history has taken us to a few hidden wonders of Sicilian antiquity that not even Roberta had seen before. Previously, we toured the ancient Greek temples and theatres in the coastal cities, explored Norman cathedrals and spent time on the Aeolian Islands, but this was our first time travelling away from the coast.

Mt. Etna

Mt. EtnaAs we drove inland from the Ionian sea, away from Mount Etna’s ever-watchful cyclopian eye, Sicily became more arid and the countryside unfolded like ripples of roasted ricotta. The roads were in good nick, there were few cars, and the view transformed with every mile, winding over a wheaten, sun-dried land — the grain fields that once fed an ambivalent Rome. There has been a human presence here for 16,000 years. Before that, giant swans and Pygmy elephants ranged. When the Greeks arrived in the 8th Century BC they found remains of a creature that had a massive skull with a large cavity in the centre of its forehead, and naturally assumed the island was inhabited by cyclopses, rather than small elephants. Persephone, the mythological embodiment of Spring and fertility, is said to have been gathering flowers with nymphs in a field near here when Hades blasted through a fissure in the earth and dragged her into the underworld. The result was famine and drought. I suggested to Roberta that we make a diversion to Leonforte as part of the research I needed to do for a book I am writing.

Like a lion surveying the savannah, the town stood high on the terrain. During Sicily’s Byzantine period, and later under the Muslim Emirate of Sicily, it was fortified. In 1610 Nicolò Placido Branciforti founded a city here, naming it Leonforte in tribute to his family's coat of arms. And in the summer of 1943, Leonforte was a large, modern town by Sicilian standards, with around 20,000 natives living alongside Germany’s 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment.

Leonforte, Sicily

Leonforte, SicilyIn July 1943, the 1st Canadian Division participated in the Allied invasion of Sicily, the first major pushback against the fascists in the Second World War. After landing on the beaches in the southeast of the island, they had advanced with little resistance against Sicilian and Italian forces. Still, communications, bridges, and culverts had been systematically destroyed by the retreating Germans, who then scattered mines everywhere. Because of its high iron content, the lava soil made it harder to detect mines in Sicily which caused the Allies long and serious delays.

“Drive the Canadians hard,” ordered General Montgomery, and hard they were driven, over steep sun-caked hills and through fiery valleys and across the barren Sicilian countryside. It was so hot that medical orderlies could not get accurate readings because their thermometers would not drop below the 102-degree mark. July is not among the months recommended for tourist travel in Sicily. But no one had told the men of the 1st Division that, eh.

Montgomery addressing Canadian troops in Sicily

Montgomery addressing Canadian troops in SicilyIn late July, the Canadians were given the unenviable task of taking Leonforte from the Germans. The approach to the town was a steep ravine, spanned by a long bridge that German engineers had destroyed before the Canadians arrived. While under heavy fire, four of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment’s rifle units managed to negotiate the ravine and enter Leonforte at midday. German and Italian defenders, now reinforced by tanks, launched a furious counterattack. As the sun set, the Loyal Edmonton Regiment was surrounded by enemy forces and completely cut off in the medieval town’s centre. But as the enemy closed in, they held their position.

“We were in the northeast corner of the town,” wrote Major Henry Bell-Irving. “My idea at the time was that we're here, and we'd better stay. I thought we might find something relatively strong that we could hold, and stay there until somebody caught up. There were German tanks in the street, and I can remember lying in the ditch with a tank right alongside me, and another firing along the ditch with tracer. There was tracer all over the place. We tried to throw grenades into the tanks, but it was quite hopeless.”

During the night, a Sicilian boy with a note addressed to "any Canadian or British Officer" managed to slip through German lines and deliver the message to the commander of the 2nd Brigade. That brave ragazzo had thrown the encircled Canadians a life line. The next morning, crossing a bridge that had been hastily erected before dawn across the ravine by Canadian engineers, tanks and anti-tank guns arrived and attacked the town. German troops attempted to counter the assault, and vicious house-to-house fighting ensued. By noon, however, Leonforte was entirely in Allied hands and Canadian pipes and drums played in the town square.

Canuks aren’t known for their imperial aspirations. Canada was colonized but not a colonizer. And yet, for a brief spell in history, we occupied this part of Sicily. I wish that made me proud, but the battle has a darker side. In their book, The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory, Samuel W. Mitcham and Stephen Von Stauffenberg allege that Canadian soldiers shot dead unarmed German pris

oners in full view of their comrades who were still fighting. Canadian Armed Forces have never acknowledged that war crimes were committed here. But the Germans claim it is the reason the fighting was so fierce. “This occurrence soon became known throughout the division and heightened its determination to resist,” said General Eberhard Rodt, commander of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. The occurrence is impossible to verify as most of those who survived have since passed on. Google “war crimes by the Loyal Edmonton Regiment in Sicily” and nothing comes up. Another Sicilian mystery goes unsolved.

Roberta and I found an idyllic spot in an olive grove surrounded by cedars overlooking Leonforte, and tucked into our picnic of delicacies. At midday, the town’s terracotta and mustard-walled buildings glowed like a beacon. Our picnic owed much to the sacrifices made here on this now comely and peaceful battleground. We raised a glass of rustic wine for the fallen, friend and foe, the many young Canadians, Italians and Germans who gave their lives here. And unlike most of the many wars fought over Sicily since time immemorial, this one was for a good cause.

May 21, 2021

What the Funk's Happening?

When I was young I caught a dose of the Funk. I was eight. It was 1970, a year when you could look up at the Moon and say, “there are people up there.” We were living in Ibadan, Nigeria. James Brown was coming to town. In the aftermath of a brutal civil war, Nigerians were ready to get a brand new bag on. All day long our houseboy Alfred, my Yoruba friend and mentor, played ’Sex Machine’, and danced to and/or sang along with, “Stay on the scene, (get on up), like a sex machine, (get on up)”. In my teens, the Funk would strike again and again, like a persistent boyhood fever. “Ow!”

The next time I was living in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania. Aged 13, I’d already had my first puff of marijuana so why not resample the Funk. At the International School of Tanganyika, Kevin, a black American student hit me up with a triple whammy: Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions, Earth, Wind and Fire’s Gratitude, and the Jackson 5’s Dancing Machine. Sure, this was mainstream black music, tamed by white sensitivities, but it had something of the Funk to it, and a whole lotta soul. Kool and the Gang’s ‘Spirit of the Boogie’, mind you, was pure Funk. I felt it in my groin. “Cause when the boogie come to get you / You ain't got nowhere to go“. From then on I couldn’t control my dancing feet. The best discos at the Yacht Club were the ones where the Funk got top billing. I’d hear Van McCoy’s ‘The Hustle’, War’s ‘Low Rider’, George McCrea’s ‘I Get Lifted’, or David Bowie’s ‘Fame’ and get all loose and funky like a bowlegged monkey to the beats. White boys can dance.

In 1978 the fullness of the Funk finally found its way into my ear. Trapped in Tananarive, the capital of Madagascar, for a week on my way home from boarding school in Fort Dauphin, I hung out at a clubhouse run by the Marines who guarded the US Embassy. It had a bar, a pool table, and a high-end stereo. Marines are dedicated followers of the Funk, I’d soon find out. I heard Parliament, Bootsy Collins, and Funkadelic whose Maggot Brain was a trip, perfectly in sync with a marijuana joint. One Marine showed me how to twirl a pool cue in time to ‘One Nation Under A Groove’.

Talking Heads’ Remain In Light, released the year I repatriated, was a turning point in the Funk, and in my own musical journey. My family record collection included Shakara, an album by Fela Kuti that is credited with being an essential influence on Remain in Light. Raised on African polyrhythms, I could relate to that ethno-funk more than I could my home and native land. When I heard to the album’s hit song, ‘Once In A Lifetime’ for the first time, I was surprised, elated and grateful. It was as if Talking Heads had heard the quarrel between my heart and head and turned it into music.

It begins with a sonic boom, a blow to the solar plexus — drum, bass, and synth fused into one explosive note — then takes off on a fiery trajectory, driven by looping grooves, an odd time signature, and a myriad of instruments, arranged by producer Brian Eno into an exquisite confusion, like an open market in Ibadan.

‘Once In A Lifetime’ confronted me. “And you may ask yourself, "Well... how did I get here?” sings David Byrne, who later said the song was about the unconscious: "We operate half-awake or on autopilot and end up, whatever, with a house and family and job and everything else, and we haven't really stopped to ask ourselves, 'How did I get here?'" That certainly was the burning question in my mind at the time. How the funk did I end up feeling like a foreigner in my passport country, searching for an identity? Living in the gloomy metropolis of Toronto only intensified that culture shock. But my dissonance could always be soothed by the Funk.

Not until it all got rolled into one delicious funk-cicle did I stand up and finally pay full attention to the Funk, tho. The year was 1985. I'd just dropped out of university and was on a year-long westward trek from British Columbia to England (though at the time I was oblivious as to its duration and destination). On the way I stayed with my folks in Addis Ababa. As I’d done before, I hung out at the Marine House. One night a funk-loving Grunt put on Prince’s Purple Rain. Raised on a diet of rock and soul, I immediately recognized the bold and brilliant act of crossover that this new, fresh funk-rock signified, and I danced my ass off to that jam. The Funk would never be the same again.

April 3, 2021

Cross Culture Odyssey: Memoir of a Repat - Prelude

“Do you suppose that you alone have had this experience? Are you surprised, as if it were a novelty, that after such long travel and so many changes of scene you have not been able to shake off the gloom and heaviness of your mind? You need a change of soul rather than a change of climate.” — Seneca

My passport is my most valued possession. I keep it close to hand, like a sidearm or a manifesto for a revolution that I have sworn to bring about. It is packed with security features: holograms, complex graphics and indecipherable cryptograms. It bears some clues to my identity, not just my identifying features but my actual identity. Imprinted into the pages of that thin book, in faded ink, are all the dates and places that pinpoint my life story. It has been scrutinized, and sometimes confiscated by corrupt border officials. Oddly, I identify more with failed states than I do my own passport country, whose good standing in the international community has eased my passage across the globe. I could not care less about citizenship and nationalism. First and foremost I am an Earthling. Second, I am a global nomad. Freedom of movement across the planet is what I care most about, it is the most precious thing we can have as human beings.

They did not stamp my passport when I arrived. It seems they no longer stamp passports upon reentry. Entry stamps used to be an art form. Travellers in the 1970s were subjected to an array of clever acronyms. Best known is the SHIT stamp: Suspected Hippie In Transit. Scruffy undesirables that trailed across Southeast Asian borders would have ‘SHIT” stamped in their passports. They never stamped it in mine. While I was travelling solo through the region in the mid 1980s, two of my passports were stolen in six weeks. The authorities suspected I was selling them and put me on a watch list. I imagine they still have a dossier with my name on it. In Kampala, after drinking one too many Extra Strong Brew’s, I lost a third passport to stupidity. And on a wild and windy night on the Kenyan coast —while I slept in a four poster bed on the second floor of my friend’s ocean-front villa with the bedroom’s beveled glass doors wide open to the elements, as waves crashed against coral cliffs with a steady, fat beat, and palm fronds danced like ravers in the wind, and all that aural delirium was reverberating through my unconscious mind — a stealthy band of thieves snuck into my bedroom and made off with my MacBook Pro, my portable speaker, and a travel wallet containing US dollars and my passport.

When I discovered the theft, I called the police. Two hours later, a pot-bellied officer and his hijab-wearing adjutant showed up to launch an investigation. They took my statement and particulars and inspected my room. They quickly deduced that the thieves had climbed up the outside wall of the house and entered from the terrace. Searching the grounds for any clues the robbers may have left behind, we followed a set of footprints to an adjacent beach. There, laying face down on the soft white sand a few feet from the surf, like a drowned migrant, was my passport. For all I knew, the cops were in on the crime and had simply dropped it there while I was not looking. Sykes monkeys might have taken it. Who cares? I had my damn passport back.

Big boots. Small planet. Once I collected all the expired passports still in my possession and made a spreadsheet from the dates and places. By the age of 21, I had lived in seven countries on three continents and travelled more than 100,000 miles, circling the globe thrice.

Not everyone wants to travel. Some people never leave the town they were born in. Some only travel within countries that resonated with their own beliefs. These days people avoid travelling by air because of terrorism, viruses or climate change, and will travel as far as they can by rail, road, and sea instead. Psychonauts travel in their own minds. Refugees travel through no choice of their own. Migrants choose to travel and arrive just as weary. Stoics like Seneca shunned travel as a distraction from one’s self, fleeing the life one has created. Travel is not for everyone. But like it or not, we all travel. Even if we stay put, we travel. Because as it moves through space, the Earth is always in motion: rotating, wobbling, and orbiting the Sun. Your position on Earth creates a pattern in space, what I call your chrono-spatial trajectory. Even if you stay put, the planet’s motions ensure you will have a chrono-spatial trajectory, one that resembles one of those coiled telephone cords from 30 years ago. Remember when one of those got so tangled it was impossible to restore it to its original shape? That is my chrono-spatial trajectory.

My whole life I have been in orbit, spinning around the planet, unable to return home. I am like a forgotten ape aboard a rusty space capsule launched in the early years of the Rocket Age. I have been falling to Earth ever since. But every time I get close to reentry, a solar flare, or a piece of space junk, or that bone that the man-ape hurls in 2001: A Space Odyssey pushes me back up into orbit again. I may never return to Earth. Growing up in Africa and Asia during the 1960s and 70s turned me into a terminal global nomad. They say variety is the spice of life, but I have yet to find a recipe that palatably blends the disparate cultural ingredients to which I have been exposed. I am my own melting pot. And I have a backstage pass to the world.

Like my father, I am not a joiner. My allegiances are few, except to the causes of rationality, enlightenment, and truth. I have lived all over the world. Those experiences have given me rare insight into the workings of our planet. I cannot be swayed by the knee-jerk polemics of myopic people who see less than I do. I am not into alternative lifestyles. Green tea, yoga, and veganism are not going to fix my life. I am. I do not need help. I eat healthily, make ethical consumer choices, and try to keep my carbon footprint small. Globetrotting is incompatible with finicky dietary needs. Nothing offends a host like turning your nose up at their fare. Otherwise, I make my own decisions and do not allow those who I do not love to interfere.

I do not believe the planet needs me. But I need the planet, like a junky needs smack. As someone who has dropped out of three universities, lived on four continents, and had five careers, I do not fit any social profile. I once believed there would be an end to this nomadic life, that I would one day repatriate to my home and native land and be sedentarily content. Usually I am quick to adapt to a new surrounding and can fit in anywhere. So why not Canada?

It may sound ungracious of me to bellyache about an upbringing as rich, diverse and exotic as mine. It shaped my worldview, made me a world citizen. Sure, I bounced from school to school but I still got an exceptional education. And if I could go back in time, I would not change a bit of it. OK, maybe a bit. Knowing what I know today, I might try to harbour less grief, not rebel when it serves no purpose, and stay in touch with my passport country, maintain better ties with my kin. Being a global nomad, a Cross Culture Kid, a hidden immigrant is a double-edged sword. Nothing good comes without a price. Mine is homelessness.

This book is about my struggles with repatriation, with making a home in my homeland. It is a memoir about the uneasy transition I have faced, again and again, in returning to my passport country, and the reasons why global nomads find it so damn hard to repatriate. In transitioning to repat, after a lifetime as expat, I confront some of my poor choices, understand the reasons for them, and try to discover who I really am. My hope is that, as I begin to take some agency in my life, I will get over myself, regain my integrity and become a better man.

Third Culture Odyssey: Memoir of a Repat - Prelude

“Do you suppose that you alone have had this experience? Are you surprised, as if it were a novelty, that after such long travel and so many changes of scene you have not been able to shake off the gloom and heaviness of your mind? You need a change of soul rather than a change of climate.” — Seneca

My passport is my most prized possession. I keep it close to hand, like a sidearm or a manifesto for a revolution I’ve sworn to bring about. It bears some clues to my identity, not just my identifying features but my actual identity. Imprinted into the pages of that thin book, in faded ink hieroglyphs, are all the dates and places that pinpoint my life story. It is packed with security features: holograms, complex graphics, and indecipherable cryptograms. It has been scrutinized by many, and sometimes confiscated by corrupt border officials or agents of failed states across the world. Oddly, I identify more with those failed states than I do my own passport country, whose good standing in the international community has nonetheless eased my passage across the globe. I could care less about citizenship and nationalism. First and foremost I’m an Earthling. Second, I’m a global nomad. Freedom of movement across the planet is what I care most about, it is the most precious thing we can have as human beings.

They didn’t stamp my passport when I repatriated. It seems they no longer stamp passports upon reentry. Entry stamps used to be an art form. Travellers in the 1970s were subjected to an array of clever acronyms. Best known is the SHIT stamp, meaning Suspected Hippie In Transit. Scruffy undesirables that trailed across the Thai or Malay borders would have ‘SHIT” stamped in their passports. Twice in six weeks, while I was travelling solo through South East Asia in the mid 1980s, my passport was stolen. The authorities suspected I was selling them and put me on a watch list. I imagine they still have a dossier with my name on it. In Kampala in 2006, after drinking one too many Extra Strong Brew’s, I lost a third passport to stupidity. And then there was that wild and windy night on the Kenyan coast —while I slept in a four poster bed on the second floor of my friend’s ocean-front villa with the bedroom’s beveled glass doors wide open, as waves crashed against the coral cliffs with a steady, fat beat, and palm fronds danced in the wind like ravers, and all that aural delirium was reverberating through my unconscious mind — when a stealthy band of thieves snuck into my bedroom and made off with my laptop, my portable speaker, and a travel wallet containing US dollars, mementoes, and my passport.

When I discovered the theft the next morning, I called the police. Two hours later, a pot-bellied officer and his hijab-wearing adjutant showed up to launch an investigation. They took my statement and particulars, inspected my room, and quickly deduced that the thieves had climbed up the outside wall of the house and entered from the terrace. Searching the grounds for any clues the robbers may have left behind, we then followed a set of footprints to an adjacent beach. There, laying face down on the soft white sand a few feet from the surf, like a drowned migrant, was my passport. For all I knew, the cops were in on the crime and had simply dropped it there while I wasn’t looking. Sykes monkeys might have taken it. Who cares? I had my damn passport back.

I once collected all the expired passports that were still in my possession and created a spreadsheet from the dates and places. By the age of 21, I’d lived in seven countries on three continents and travelled more than 100,000 miles, circling the globe three times.

Not everyone wants to travel. Some never leave the town they were born in. Some only travel within their own countries, or their own languages and cultures, brooking no destinations but those that resonate with their own beliefs. Some have simply avoided travelling by air because of a fear of terrorism, viruses or climate change, and will instead travel as far as they can by rail, road, and sea. Some are psychonauts who travel in their own minds. Some travel through no choice of their own. Stoics like Seneca shun travel as a distraction from one’s self, believing one is simply fleeing the life one has created. Travel’s not for everyone. But like it or not, we all travel. Even if we stay put, we travel. That’s because the Earth is always in motion: rotating, wobbling, and orbiting the Sun as it moves across the Universe. Your position on Earth creates a pattern, what I call your chronospatial trajectory. Even if you stay put, the planet’s motions ensure you’ll still have a chronospatial trajectory, one that resembles one of those coiled telephone cords from 30 years ago. Remember when one of those got so tangled up it was impossible to restore it to its original shape? That’s my chronospatial trajectory.

My whole life I’ve been in orbit, spinning around the planet, unable to return home. I’m like a forgotten ape aboard a rusty old space capsule launched in the early years of the Rocket Age that’s been falling to Earth ever since, but every time I get close to reentering the atmosphere a solar flare, or a piece of space junk, or that bone the man-ape hurls in the movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey bumps me back up into orbit again. I may never return to Earth. Growing up in Africa and Asia during the 1960s and 70s turned me into a terminal global nomad. They say variety is the spice of life, but I’ve yet to find a recipe that palatably blends my disparate cultural ingredients. I am my own melting pot, and I’ve got a backstage pass to the world.

As a global hobo who’s dropped out of three universities, lived on four continents, and moved through five careers, I don’t fit any social profile. I once believed there’d be an end to this way of life, that one day I’d repatriate to my home and native land and be sedentarily content. But in reality, uprooting as an infant and then every three years or so, sometimes continents at a time, created a rootless, restless nature in me that cannot be quelled. I’ve been on a lifelong quest to belong, to find a place to call home, settle, and to find my identity. But to stay balanced I must continue to move forward.

It may seem sullen to bellyache about an upbringing as rich and exotic as mine was. Truth be told, I wouldn’t change any of it for the world. But knowing what I know now, I might try to carry less grief, avoid being a rebel when it serves no purpose, and stay connected to my passport country, maintain ties with my relatives back home. Global nomadism is an education beyond any other, it helped shaped me into the world citizen I am. But nothing good comes without a price. Mine is homelessness. This book is about a reluctant repat trying, after a lifetime as an expat, to find home in his homeland. It’s a memoir about the uneasy transition I’ve faced upon reentry to my passport country, again and again, and the reasons why global nomads find it so damn hard to adapt. It’s also about the diversions I took, my emotional detachment, and the smorgasbord of self-medicating I did to try avoid the trauma of facing up to the truth about who I am: a deeply flawed human being. In it, I confront my choices and try to become a better person.

August 12, 2018

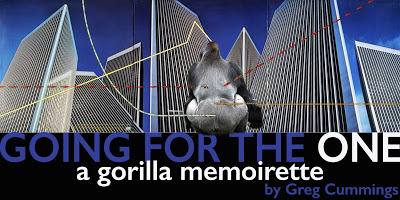

GOING FOR THE ONE Part 12 - My DNA

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Cochin} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-indent: 18.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; min-height: 17.0px} p.p3 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin} p.p4 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-indent: 18.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin} p.p5 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 36.0px; font: 12.0px Cochin} p.p6 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 36.0px; text-align: right; font: 12.0px Cochin} p.p7 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; min-height: 17.0px}

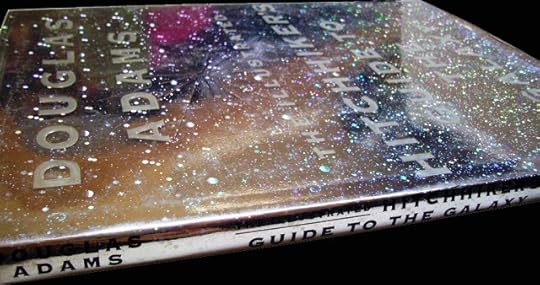

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 18.0px Cochin} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-indent: 18.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; min-height: 17.0px} p.p3 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin} p.p4 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-indent: 18.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin} p.p5 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 36.0px; font: 12.0px Cochin} p.p6 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 36.0px; text-align: right; font: 12.0px Cochin} p.p7 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; min-height: 17.0px} The last time I met Douglas Adams was on the morning of 26th April 2001, in the mezzanine lobby of the One Aldwych Hotel in London. I had not seen him since he moved to Santa Barbara to adapt a screenplay from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy for Disney. American lifestyle had taken its toll, and he attempted to disguise the extra pounds with two-tone attire: white shirt and black trousers. His hair was closely cropped and white. He blended in faultlessly with his surroundings. “How can I help,” he smiled.

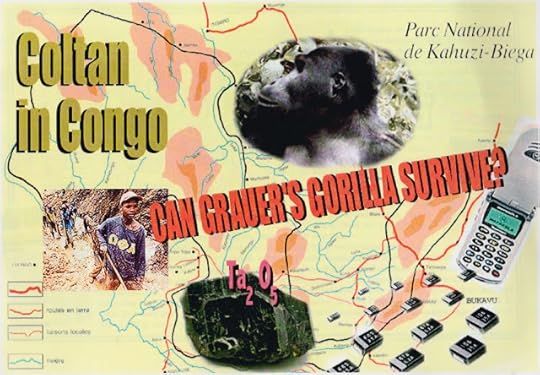

“Coltan,” I said, “an entirely new threat to the gorillas. The mining of it in eastern Congo is driving the Eastern lowland gorilla to extinction. Apparently it’s processed into tantalum, which is indispensable to mobile phones and computers.”

“So now the tech industry’s the bad guy,” sighed Douglas. He sat back and crossed his imposing limbs.“Talk to Nokia,” he said, “they’re the industry leaders in mobile phones. And see if you can’t get an article into Wired about it. Ask John Perry Barlow to pen something.”

“I’m writing an appeal,” I said, “to send to all the companies involved.”

“Not an appeal,” he said, gazing up at a pair of azalea bushes hanging above his head, “write your letter to inform, ask them to take the initiative. And make sure you send me a copy of the draft before you circulate it.”

Following his counsel to the full, I then sent an open letter to the tantalum industry, which sparked an upswell of public support for the gorillas, and launched a campaign led by Arthur C. Clarke and Leonardo DiCaprio that resulted in new legislation in the United States.

But I never saw Douglas again. Two weeks later, while working out at a gym in Santa Barbara his heart stopped beating and he died instantly. He was only 49. I was in San Francisco when I heard the terrible news. We were scheduled to meet up that week. The loss was too great for words. As well as my friend, my patron, and my mentor, Douglas was the gorillas’ best hope.

Five days later I was with Mike Backes in LA when we heard his funeral was going to be held that afternoon. “Let’s go,” said Mike.

“But we weren’t invited,” I said.

“So what, let’s drive down there anyway.”

“We won’t make it in time. The service starts in less than an hour, in Santa Barbara, which is at least 90 minutes drive away.”“We’ll take the Porsche,” said Mike.

We made it in 45 minutes, crept in and stood at the back of chapel. An organist was playing The Rolling Stones, ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want.’ Douglas’s coffin seemed to stretch from wall to wall. How did they find a tree tall enough?

Science has lost a friend, literature has lost a luminary, the mountain gorilla and the black rhino have lost a gallant defender (he once climbed Kilimanjaro in a rhino suit to raise money to fight the cretinous trade in rhino horn), Apple Computer has lost its most eloquent apologist. And I have lost an irreplaceable intellectual companion and one of the kindest and funniest men I ever met. - Richard Dawkins, obituary for Douglas Adams, The Guardian

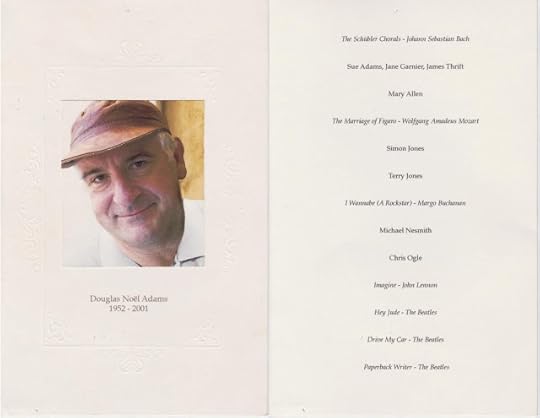

“Douglas Noel Adams, 1952-2001” read the invitation I received 4 months later, to the memorial service at St Martin’s in the Field, London. Everyone came to bid a final farewell to DNA. The ushers collected donations for rhinos and gorillas. Following the service, a group of his friends walked through Leicester Square together, to attend his wake at the Groucho Club in Soho. I was proud to walk among them.

At the Groucho Club I worked the room, Douglas wouldn’t have wanted it any other way, chatted to Peter Gabriel, another AppleMaster whom Douglas had recruited to the cause. It was our first time meeting, though I’d been a fan of his music since high school. “You’re not going to like me,” said Gabriel in a raspy voice. “I’ve had a bonobo in my studio playing keyboards.”

“You’re kidding me,” I laughed.

Peter Gabriel

Peter Gabriel“No, it’s true. The bonobo speaks sign language and has an extensive vocabulary. So we asked her to come to my studio and play the piano. We had to bribe her with Jell-O, but she played pretty well."

“Can’t wait to hear what that sounds like,” I said.

“What do you think about gorillas communicating with each other using video conferencing?” asked Gabriel. “Putting monitors in their habitat to see if they make contact with each other.”

“The equipment would have to be ruggedized to withstand a hell of a beating,” I said. I then told him about the Media Lab’s idea of making a hologram of a silverback.

I found Storm Thorgerson talking to his Pink Floyd mates, asked him if he’d design our annual report. “Go on, Storm," said Dave Gilmour, "design their annual report."

Dave Gilmour"If I did design it," said Storm with bored contempt, "there'll be no fucking gorillas in it."

Dave Gilmour"If I did design it," said Storm with bored contempt, "there'll be no fucking gorillas in it.""No gorillas," I laughed, “I don’t get it.”

“Maybe a hand print or two, but that's all.”

“Why?”

”For the sad fact that there are far too few left in the wild,“ said Storm.

Bringing to a close this tribute as tall, aged, and deeply fissured as an old-growth Douglas Fir, while Pink Floyd sings, “Wish You Were Here,” I can see Douglas’s congenial full moon face, amused no doubt by some scientific absurdity. So much has happened in the 40 years since The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy first hit the airwaves, and yet the wit is still fresh. I wonder how, after so long away, such an avowed atheist as Douglas can still make his presence felt. Welcome back, old friend. I’ve missed you. It’s twenty years on, but your plan for a once-and-for-all fund to save the gorillas is no less compelling. $35 million is chump change for today’s tech titans. Surely one of them will read this story and step up with the cash needed to guarantee the survival of a species of great ape. “A bargain at the price!” says Douglas.

In loving memory my friend and mentor, Douglas Adams, the coolest dude in the Universe

In loving memory my friend and mentor, Douglas Adams, the coolest dude in the UniverseAugust 5, 2018

GOING FOR THE ONE Part 11 - Baby You’re A Rich Man

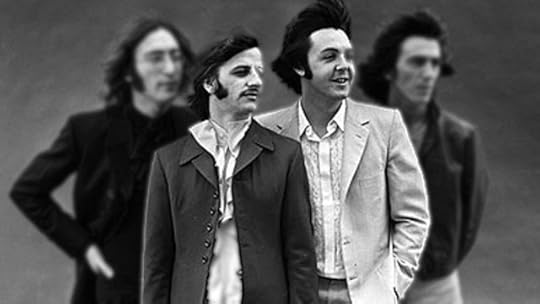

The celebrity car boot sale was an unqualified success. Among the many beautiful gifts donated were Richard Dawkins’s complete works signed, an illustrated Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, also signed, and a varicoloured Senegalese vest that Youssou N’Dour had given to Peter Gabriel when they toured together. But the item that fetched the highest price was an artwork painted by Sir Paul McCartney called ‘Lucy In The Sky with Puppies’, which sold for $7,500.

Sir Paul was so delighted by this that he told his assistant Shelagh Jones to write to me asking how he could further help the cause. I suggested he host a benefit lunch for the gorillas at his office in Soho Square, invite the titans of the tech industry. Sir Paul agreed. The event was scheduled for June 16th 1999. We were back in business.

Shelagh Jones gave me a tour of the venue, a stately wood-paneled dining room on the second floor of MPL Communications, where Sir Paul kept his psychedelically painted piano from Sgt. Pepper’s. “He’s suggested doing a sing-song after lunch,” said Jones.

MPL Communications, Soho SquareAlthough the McCartneys had by then made several donations to the cause, I had yet to meet Linda and Paul in person. I was thrilled by the prospect. However, Shelagh informed me that Paul could not retain information for more than 24 hours. “So, if you want him to do our bidding with the billionaires,” she smiled, “you’ll have to forgo meeting him until the day before the lunch.”

MPL Communications, Soho SquareAlthough the McCartneys had by then made several donations to the cause, I had yet to meet Linda and Paul in person. I was thrilled by the prospect. However, Shelagh informed me that Paul could not retain information for more than 24 hours. “So, if you want him to do our bidding with the billionaires,” she smiled, “you’ll have to forgo meeting him until the day before the lunch.”I sent invitations out to every one of the 800lb gorillas from the tech industry that I’d come into contact with while setting up the endowment appeal, asking them to attend an exclusive lunch with Sir Paul to talk about saving a species. While Steve Jobs and Larry Ellison were both keen, Paul Allen was prevaricating.

Then Shelagh called to say Ringo Starr had also agreed to join the luncheon. I sent Douglas the news, he immediately replied:

That’s very good news indeed. Two Beatles together make it a hugely unique special occasion, and I’m sure you could then broaden your range of targets. My guess is that if you invite SJ and LE and whoever else, you will probably call PA’s bluff. How could he not want to be there? But now what about Ted Turner and Jane Fonda? What about Steven Spielberg? What about Michael Eisner?- Email from Douglas Adams to Greg Cummings

Over the next two months, Jobs and Ellison would drop out of the event due to conflicting schedules, but Paul Allen confirmed he was coming. Reportedly worth $30 billion at the time, we felt confident our singular guest would make a handsome donation.

But we hadn’t banked on Ringo. With just six days to got before the event, Shelagh Jones called again. “Before he agrees to participate, Ringo wants to know how much Paul Allen’s going to give.”

My heart raced. Alarm bells began to peal. In desperation, I sent off a cluster of emails to the highest levels. “What, the Beatles are the door prize?” asked Mike Backes. Nathan Myhrvold sent a more considered response:

I am not sure what to say, One fairly obvious point is to double and triple check that Paul McCartney isn’t going to flake on you at the last minute for the same reason. That would be a disaster.

I have no idea what Paul [Allen]’s expectations are. My belief, based on what you have told me so far is that the lunch is about making the ask, and that this was not a done deal. If I think that, my guess is that Paul Allen thinks that too, unless you have described things very differently to him.

You can’t very well demand the donation up front if that isn’t what Paul is expecting. Even broaching the topic could be very off-putting. Note that I am not speaking for Paul, maybe he would not feel that way, but I sure would, and I think most people would.

Paul knowing that Larry won’t be there may be a good sign, but don’t be presumptive. What if Paul is thinking of donating say $5 million? This would be a very generous gift by any absolute standard, even if it is less than you want. But maybe he is thinking about doing the whole thing. At this stage you pretty much have to go through with it.

The mix up with Ringo is very awkward, and very odd. If lunch with the Beatles was a $100,000 a plate fund raising luncheon, then it is proper to make it prepaid. But this isn’t that sort of thing - you don’t typically have a $30 million a plate fundraising luncheons. At this level of philanthropy it would be odd to ‘and, if you make the donation you get lunch with the Beatles.’

The main saving grace is that Ringo is the least important of the Beatles - McCartney is still a good draw!

If McCartney does not have to personally make the ask, but at the very least I would hope that he says how important it is that the gorillas be saved etc, and then you make the ask.

If you show your film, and make a presentation on the overall programe, you might not need to literally ask. But, then again, you may well have to.

One minor point is that it would be awkward if McCartney congratulates him on the donation before it is clear that he has made it.

I am not sure what else to say other than good luck!- Email from Nathan Myhrvold to Greg Cummings

In the end McCartney did flake, got behind Starr’s malapropos demand. My hand was forced; I wrote to Paul Allen explaining that an eleventh-hour hiccup had occurred. “Sir Paul and Ringo are keen to meet you but have asked that there be a confirmation of a donation first. I know this is very unconventional and certainly not what you were led to believe would transpire at this luncheon. My only hope is that you understand our predicament and agree to proffer an idea of what you would like to donate. Subsequently, the lunch will go ahead as planned and we can launch our $35 million endowment for the endangered mountain gorillas. Generations will thank you for it.”

Allen replied simply, “What?”, which then dealt the coup de gras to our endowment appeal.

I sat on a park bench at the summit of Primrose Hill between a trio of Rowan-whitebeam cross trees. The air bristled with the freshness of Spring. A strong wind blew, rustling through the newborn leaves. Still, Mother Nature’s soothing hush tones weren’t enough to keep me from sobbing. The bottom of my world had just dropped out.

Looking down at the mock-up animal habitats in Regent’s Park Zoo, I wondered, “Is this what the future holds for the gorillas?” I reached over the top of my head with my right arm and stroked the left side of my face, like a gorilla might do, wiped the tears away. It was comforting. No question, I’d let the big fellas down. Handing in my resignation would have been the honourable thing to do but I stayed on.

It was the turn of the millennium, a new century. The Dot Com bubble burst. PlayStation 2 and GameBox were released. The first resident crew entered the International Space Station. A new generation of spaceborne imaging radar was launched on Endeavour, creating the elevation models that are today used in geographic information systems.

Much good came from of our quest for a $35 million endowment. We had a bunch of great new patrons, including Douglas Adams, Mike Backes, Richard Dawkins, Nathan Myhrvold, and Michael Crichton. And we had Apple sponsorship. In May 2000, I was interviewed by Apple Hot News about how we were using the donated equipment:

This is where Apple technology can really help,” Cummings says. “A few weeks ago, I sent an email through my wireless modem on the PowerBook while I was sitting at the foot of the volcanoes in Uganda. I spoke to my communications consultant in London from within the park, not 20 minutes after sitting with the gorillas. We can do miracles with our Apple technology. Can you imagine? We can post digital images through the GSM connection after witnessing a gorilla birth. The possibilities are endless.- Apple Hot News, May 2000

Imagine where the gorillas would be today if our endowment appeal had been successful, the standard of innovation in conservation we would be enjoying by now. We’d have real time gorilla trekking in their habitats using VR, GorillaCams in the forest monitoring their conservation, thermal cameras to trigger automated alerts for rangers when suspected poachers cross into parks, haptic devices leading gorillas down the path of least resistance, and a high-tech gorilla conservation centre featuring an exhibit of silverback holograms. Most importantly, we’d have peace of mind.

July 29, 2018

GOING FOR THE ONE Part 10 - Oh No, Mr Bill!

Timing is everything… On the same day as our meeting with Bill Sr at the Edgewater, a Congolese army major broadcast the following message from a radio station in eastern Congo: “People must bring a machete, a spear, an arrow, a hoe, spades, rakes, nails, truncheons, electric irons, barbed wire, stones, and the like, in order, dear listeners, to kill the Rwandan Tutsis.”

All hell had broken loose, again. The Second Congo War, a.k.a. the Great War of Africa had begun. It was to become the deadliest war in modern African history, directly involving 8 African nations, and 25 armed groups. Who would invest in such a place? We could not have picked a worse time to appeal to the Gates Foundation.

War wasn’t the only thing working against us. That month the US Justice Department summoned Bill Jr to the United States vs Microsoft anti-trust trial. News broadcasts throughout August, when not saturated by the Monica Lewinsky scandal, showed images of the grizzly massacres in the Congo and Bill Jr under visible duress, rocking back and forth in his chair as he gave his deposition to the Justice Department.

Barely a week after Jillian and I returned home from California, we got the news we’d been waiting for. It was a letter from Bill Gates Sr, citing the political uncertainty of the region combined with the “multiplicity of the agencies working in this area,” (I never did figure out what he meant by that) as the foundation’s reasons not to support this effort at this time.

I conveyed the sad news to a stone-faced gathering of our field staff, who’d come to London for a week of strategy meetings. “We did our best,” I said, swallowing hard, “gave this appeal its best possible chance of success. It couldn’t have helped that civil war broke out in Congo just as Gates was making his decision, but this is the very nature of the beast and the reason why a privately funded endowment is the only way to ensure mountain gorillas survive.”

It was late afternoon on the last day our meetings. My African colleagues were ready to fly home. We were drinking pints of lager at a long wooden table at the Pembroke Castle in Primrose Hill. No one was saying much. It was a dark day for the gorillas. Just then a gleaming blue Porsche 911 pulled up outside, engines roaring, and a giant man emerged, strode through the pub door. It was Douglas Adams. He had come to join us for a farewell drink.

We embraced. “Thank you for all your help in trying to make this work for the gorillas,” I said. “We’ve not yet given up hope.”

Douglas, determined to put a positive slant on things, suggested we might have to break the endowment down into more manageable chunks of money. I introduced him to my African colleagues. For the next hour he entertained them with anecdotes of when he was traveling the world in search of endangered species, writing Last Chance To See . Evident by their hysterics, they all knew the story of the obfuscating Zairian border official.

Douglas trying to figure out a trick with corks Douglas wore his heart on his sleeve and when an idea struck him, he could get quite animated about it. Often he would call me up at the office to relate some new notion he had about gorillas. One time he called to ask what I thought of the aquatic ape theory, the idea that the ancestors of modern humans were more inclined to wade in water than other great apes. I told him I thought it was a distraction from the real issues. That was me, a one-topic dilettante who only felt confident discussing subjects I had previously researched. At least I knew my gorilla shit.

Douglas trying to figure out a trick with corks Douglas wore his heart on his sleeve and when an idea struck him, he could get quite animated about it. Often he would call me up at the office to relate some new notion he had about gorillas. One time he called to ask what I thought of the aquatic ape theory, the idea that the ancestors of modern humans were more inclined to wade in water than other great apes. I told him I thought it was a distraction from the real issues. That was me, a one-topic dilettante who only felt confident discussing subjects I had previously researched. At least I knew my gorilla shit.“What about a celebrity car boot sale?” asked Douglas. “I’ll invite my friends to donate some eclectic junk, and we’ll auction it to the highest bidder, online, for the gorillas, get e-Bay to feature the auction.”

“Bloody good idea,” I said.

July 22, 2018

GOING FOR THE ONE Part 9 - Hello, (again) continued

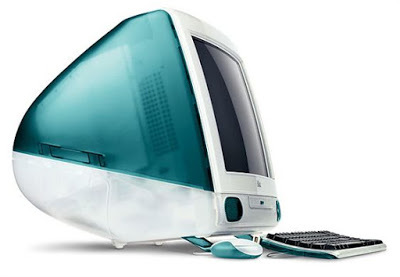

“Hello, (again)” proclaimed a giant blue inflatable computer wobbling in the warm California breeze that swept across the grounds of the Apple Corporation. The company had just rolled out its first iMac. Whether stimulated by the promise of a brighter future or the free beer, staffers seemed to have gotten their mojo back.

We’d come to see Kanwal Sharma, who ran AppleMasters, to discuss a further donation of equipment. He hadn’t given us any prior warning that our visit would coincide with such a major product launch. “Come,” said Sharma, “I’ll introduce you to my boss.”

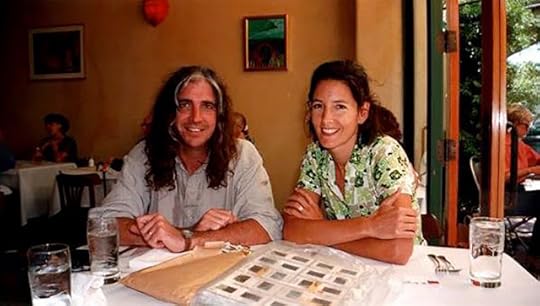

With Kanwal Sharma at Apple, Cupertino, CA

With Kanwal Sharma at Apple, Cupertino, CAStanding next to the big inflatable iMac, coolly drinking beer from a plastic cup, was Apple’s newly reinstated CEO, Steve Jobs. After we were introduced, I pitched him the gorillas. He was inattentive and punctuated each of my points with a dismissive, “cool,” like how other people say, “fuck off.” I saw straight away that my passion had no traction with him.

Jon Rubinstein, on the other hand, was quite interested in what we had to say, and asked about trekking gorillas in the wild. Getting the senior vice president of hardware engineering on our side was key. Next to him stood Jonathan Ive, the company’s thirty one year-old British designer. The iMac was his baby - the first in a range of stunningly innovative products he would design for Apple over the coming decade, including the iPod, iPhone and iPad. He was wearing a blue silk shirt identical in colour to the iMac. “How did you manage to find a shirt exactly the same colour?” asked Jillian.

“Other way around,” laughed Ives. “I bought the shirt on Bondi Beach, and then used it as the swatch for iMac’s translucent shell, called it Bondi Blue.”

“Cool!” I said.

iMac

iMacNext stop, Walt Disney Animation Studios in Burbank, to meet Kevin Lima and Chris Buck, directors of the new Tarzan animated film. They gave us a tour of the “set”: a hive of animation cells connected by corridors decorated with large images of the story’s main characters. Every frame of the movie was drawn in one of those cells, by an animator on an easel. The image would then be scanned and, with massive rendering power, made to run in sequence.

Jillian and I (centre) at Disney Animation, Burbank, CA, with Chris Buck and Kevin LimaBuck and Lima recounted the exhaustive research the team had undertaken to prepare for animating gorillas: attended lectures on primates, made trips to zoos, witnessed a gorilla dissection to learn about its musculature, even visited Bwindi in Uganda to observe mountain gorillas in the wild and gather inspiration for the setting. The movie’s sweeping 3D backgrounds were breathtakingly similar to the real thing. This required a rendering technique known as Deep Canvas, software that keeps track of brushstrokes applied in 3D space.

Jillian and I (centre) at Disney Animation, Burbank, CA, with Chris Buck and Kevin LimaBuck and Lima recounted the exhaustive research the team had undertaken to prepare for animating gorillas: attended lectures on primates, made trips to zoos, witnessed a gorilla dissection to learn about its musculature, even visited Bwindi in Uganda to observe mountain gorillas in the wild and gather inspiration for the setting. The movie’s sweeping 3D backgrounds were breathtakingly similar to the real thing. This required a rendering technique known as Deep Canvas, software that keeps track of brushstrokes applied in 3D space.We asked them if the gorillas might be the beneficiary of Tarzan’s premiere. They agreed to consider it, but in the end gave the premiere to LA Zoo.

Dinner at Emelio's, Santa Barbara, CA. (From left to right) Berkeley Breathed, Jillian Miller, Savannah Brentnal, Kai Krause, the author, Mike Backes, Douglas Adams, and Jody BoymanIn the restaurant at the end of our journey, a hero’s welcome awaited us. Gathered in a bistro on the Santa Barbara waterfront for a feast in our honour were Kai Krause, Savanah Brentnall, Jody Bowman, Berkeley Breathed, and Douglas Adams. Mike Backes arrived late in his gold Porsche 928 which he’d driven down from LA. Jillian and I regaled them with thrilling tales of our Pacific Coast journey, how we’d sealed the deal on the Gates appeal, and pitched some of the most influential people in tech. “Timing is everything,” I said. “I mean, to have shown up on the day they launched the iMac. It didn’t take much to get them to agree to a further donation of stuff.”

Dinner at Emelio's, Santa Barbara, CA. (From left to right) Berkeley Breathed, Jillian Miller, Savannah Brentnal, Kai Krause, the author, Mike Backes, Douglas Adams, and Jody BoymanIn the restaurant at the end of our journey, a hero’s welcome awaited us. Gathered in a bistro on the Santa Barbara waterfront for a feast in our honour were Kai Krause, Savanah Brentnall, Jody Bowman, Berkeley Breathed, and Douglas Adams. Mike Backes arrived late in his gold Porsche 928 which he’d driven down from LA. Jillian and I regaled them with thrilling tales of our Pacific Coast journey, how we’d sealed the deal on the Gates appeal, and pitched some of the most influential people in tech. “Timing is everything,” I said. “I mean, to have shown up on the day they launched the iMac. It didn’t take much to get them to agree to a further donation of stuff.” Douglas, who was befuddled by a magic trick that Mike had shown him, looked up and beamed proudly. “How many AppleMasters do you now have as supporters?” he asked.

“Eight,” I said.

“That must constitute an orchard,” said Backes.

Mike Backes, Los Angeles, CA, 1997

Mike Backes, Los Angeles, CA, 1997July 15, 2018

GOING FOR THE ONE Part 8 - Hello, (again)

I directed and edited a short documentary for the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund. I shot it with my pal Brian Callier on a Sony digital video camera in Sri Lanka and England. We interviewed AppleMasters Richard Dawkins and Douglas Adams, as well as Arthur C. Clarke. Back in L.A. using FireWire and a Radius Moto DV card, I downloaded the pristine digital video directly to my Power Macintosh hard drive. Then, using EditDV from Radius, I edited the video. This setup was unbelievably cool. I just plugged in the PCI card, attached a cable to the camera, booted the software, and I could move the video into my Mac. We got some footage of gorillas that fellow AppleMaster John Perry Barlow helped us shoot during his recent trip to Uganda. The gorilla clips were pretty short, so we just converted them to slow-motion with Edit DV. David Gilmour of Pink Floyd let us use some of their music, so we digitized it with SoundEdit and slapped it on the gorilla footage. Simple and fun. - Mike Backes’s AppleMasters page

An abridged copy of the Endowment ProposalIn February 1998, I hand delivered our appeal package to Nathan Myhrvold in Redmond. It contained Mike Backes’s film Time to Act, a high-res copy of the radar image of the gorilla habitat acquired by the space shuttle Endeavour, and an elegantly bound, 50-page business plan. Our proposal, how $35 million would guarantee the survival of the endangered Mountain gorilla, was well-grounded and lock-tight.

An abridged copy of the Endowment ProposalIn February 1998, I hand delivered our appeal package to Nathan Myhrvold in Redmond. It contained Mike Backes’s film Time to Act, a high-res copy of the radar image of the gorilla habitat acquired by the space shuttle Endeavour, and an elegantly bound, 50-page business plan. Our proposal, how $35 million would guarantee the survival of the endangered Mountain gorilla, was well-grounded and lock-tight. Next stop Monterey, where the Technology Engineering, and Design conference was underway. TED8 attracted a clique of well-heeled geeks. Tickets went for $2,000 a piece and had sold out in a day. German software designer Kai Krause helped me gate-crash the event. On Saturday, in the simulcast room, following a showing of David Tate’s film about the Pathfinder mission to Mars, they premiered Time to Act. I reckon it had a deliberate audience of about 60 people, including Luis Rossetto, co-founder of Wired. I got five minutes with Larry Ellison, head of Oracle Corp, gave him copies of the film and business plan. Very warm response. I even gate-crashed the “billionaires dinner”, doorstepped Jeff Bezos on a street corner afterward. “My wife handles all our charitable donations,” he said.

“Does your wife like wildlife?” I asked, as he tried to flag a taxi.

“She likes jazz,” he said.

Titans of the tech industry we're starting to take notice of our cause, to hear about our endowment appeal. The gorillas were due their day.

In Berkley with Jane Metcalf, co-founder of WIRED magazine

In Berkley with Jane Metcalf, co-founder of WIRED magazine Jillian with Louis Rossetto, co-founder of WIRED magazine

Jillian with Louis Rossetto, co-founder of WIRED magazineAfter four months of being arm twisted, Bill Gates finally asked his father, who was then director of his foundation, to look "into the Gorilla donation in more detail."

I began corresponding with the dad, Bill Gates Sr. His main areas of concern were the gorilla range state governments. “What can you to tell us about the geography and politics? What countries are involved? What action is necessary on those countries parts to effect your program? What is going on that indicates, one way or the other, that they will co-operate?”

After consulting my gorilla gurus, I sent Bill Sr a comprehensive response to his questions and then pressed him for a face-to-face meeting. I also suggested the fully wired conservation centre we planned to build be named William H. Gates III Conservation Centre. Finally, an email arrived from Suzanne Cluette, assistant director at the Foundation: “Mr Gates has asked that I respond to your request for a meeting in Seattle. We would be pleased to meet with you.”

Jillian joined me on this trip. We planned to drive down on the Pacific Coast Highway, through Big Sur, and rendezvous with Douglas Adams in Santa Barbara. First stop, Seattle, the lobby of Edgewater, at 9 am on August 12th, for our meeting with the William H. Gates Foundation.

Bill Gates SrWe sat on soft chairs beneath the balustrade. Elliott Bay was scintillating in the background. Bill Sr, a leggy man in his sixties, had dressed in blue check shirt sleeves and chinos. Suzanne Cluett, a not-for-profit veteran with hands-on experience in the developing world, asked most of the questions,. Bill Sr listened intently to our answers with eyes closed. A hotel cleaner was pushing a vacuum cleaner with the most deafening whine back and forth on the balustrade above. Nevertheless, the Gates Foundation gave us 90 minutes and Jillian and I gave the pitch of our lifetimes.

Bill Gates SrWe sat on soft chairs beneath the balustrade. Elliott Bay was scintillating in the background. Bill Sr, a leggy man in his sixties, had dressed in blue check shirt sleeves and chinos. Suzanne Cluett, a not-for-profit veteran with hands-on experience in the developing world, asked most of the questions,. Bill Sr listened intently to our answers with eyes closed. A hotel cleaner was pushing a vacuum cleaner with the most deafening whine back and forth on the balustrade above. Nevertheless, the Gates Foundation gave us 90 minutes and Jillian and I gave the pitch of our lifetimes.“We will consider it,” said Bill Sr, shaking Jillian’s hand and mine, “and let you know as soon as possible.”

After they’d left, we high-fived each other. “You know, Led Zeppelin once played footie in this lobby,” I said.

“Really?” she laughed.

“Oh yeah, baby, this is hallowed ground.”