Gernot Wagner's Blog, page 4

April 12, 2015

Talks @ Google

Alternatively, see the 90-second version of Climate Shock.

April 1, 2015

How does climate stack up against other worst-case scenarios?

[caption id="attachment_2400" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Illustration by Glen Lowry/Ensia[/caption]

Illustration by Glen Lowry/Ensia[/caption]What we know about climate change is bad. What we don’t know makes it potentially much worse. But climate change isn’t the only big problem facing society.

Opinions differ on what should rightly be called an “existential risk” or planetary-scale “catastrophe.” Some include nuclear accidents or terrorism. Others insist only nuclear war, or at least a large-scale nuclear attack, reaches dimensions worthy of the “global” label.

There are half a dozen other candidates that seem to make it on various lists of the worst of the worst, and it’s tough to come up with a clear order of which most demands our attention and limited resources. In addition to climate change, let’s consider asteroids, biotechnology, nanotechnology, nukes, pandemics, robots and “strangelets,” strange matter with the potential of swallowing the Earth in a fraction of a second.

That might strike some as a rather short list. Aren’t there thousands of potential risks? One could imagine countless ways to die in a traffic accident alone. That’s surely the case. But there’s an important difference: While traffic deaths are tragic on an individual level, they are hardly catastrophic as a class.

Every entry on our list has the potential to wipe out civilization as we know it. All are global, highly impactful and mostly irreversible in human timescales. Most are highly uncertain.

One response to any list like this is to say that each such problem deserves our (appropriate) attention, independently of what we do with any of the others. If there’s more than one existential risk facing the planet, we ought to consider and address each in turn.

That logic has its limits. If catastrophe policies were to eat up all the resources we have, we’d clearly have to pick and choose. But we don’t seem to be anywhere close. A first step, then, should always be to turn to benefit-cost analysis, which in turn is something that every U.S. president since Ronald Reagan has affirmed as a guiding principle of government policy.

Ideally, society should conduct serious benefit-cost analyses for each worst-case scenario: estimate probabilities and possible impacts, multiply the two, and compare it to the costs of action in each instance. If climate change and asteroids andbiotechnology and nanotechnology and nukes and pandemicsand robots and strangelets emerge as problems worthy of more of our attention, society should devote more resources to each.

But we can’t just hide behind standard benefit-cost analysis that ignores extremes. Each of these scenarios may also have their own variant of “fat tails,” or underestimated and possibly unquantifiable extreme events that could dwarf all else. The analysis soon moves toward some version of a precautionary principle focused on extreme events. The further we move away from standard benefit-cost analysis, the more acute the need to compare across worst-case scenarios — a comparison that is getting increasingly difficult.

How, then, to analyze these potential worst-case scenarios and decide which deserves more of our attention?

For one, only two on the list — asteroids and climate change — allow us to point to history as evidence of the enormity of the problem. For asteroids, go back 65 million years to the one that wiped out the dinosaurs. For climate, go back a bit over 3 million years to find today’s concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and sea levels up to 20 meters (66 feet) higher than today.

Asteroids come in various shapes and sizes. We begin our book Climate Shock by looking at the one that exploded above Chelyabinsk Oblast in February 2013. The impact injured 1,500 and caused some limited damage to buildings. We shouldn’t wish for more of these impacts to happen just for the spectacular footage, but we’d be hard pressed to call an asteroid of that size a “worst-case scenario.”

NASA’s attempts at cataloguing and defending against objects from space aims at much larger asteroids, the ones that come in civilization-destroying sizes. Astronomers may have been underestimating the likelihood of Chelyabinsk Oblast–size asteroids all along. That’s a problem that needs to be rectified, but it’s not a problem that will wipe out civilization. If we estimated the likelihood of a much larger impact incorrectly, the consequences could be significantly more painful.

Luckily, when it comes to asteroids, there’s another feature working for us. Science should be able to observe, catalog and divert every last one of these large asteroids — if sufficient resources are provided. That’s a big if, but not an insurmountable one: A National Academy study puts the cost at $2 to $3 billion and 10 years’ research to launch an actual test of an asteroid deflection technology. That’s much more than we are spending at the moment, but the decision seems rather easy: Spend the money, solve the problem, move on.

Strangelets are the opposite of the Chelyabinsk Oblast asteroid in that they have never been observed. They are straight out of science fiction and may be theoretically impossible. If it is possible, though, there may be a chance that large heavy-ion colliders like the one ramping up once again at CERN near Geneva could create them. That has prompted research teams to calculate the likelihood of a strangelet actually happening. Their verdict: Concrete numbers for the upper bound hover between 0.0000002 percent and 0.002 percent. That’s not zero, but it might as well be.

So yes, swallowing the entire planet would be the ultimate bad — clearly worse, say, than melting the poles and raising sea levels by several meters or feet. Stranger things have happened. But strangelets very, very, very likely won’t.

The same could be said of autonomous robots reproducing and taking over the world. It’s not that it can’t ever happen, but it certainly hasn’t happened before. That doesn’t mean it won’t, but if forced to put a probability on the eventuality, it would be very, very small.

If we could rank worst-case scenarios by how likely they are to occur, we’d have taken a huge step forward. If the chance of a strangelet or robot takeover is so small as to be ignorable, probabilities alone might point to where to focus. But that’s not all. The size of the impact matters, too. So does the potential to respond.

What then, if anything, still distinguishes climate change from the others remaining: biotechnology, nanotechnology, nukes and pandemics?

For one, the relatively high chance of eventual planetary catastrophe. In Climate Shock , we zero in on eventual average global warming of 6°C (11°F) as the final cutoff few would doubt represents a true planetary catastrophe. Higher temperatures are beyond anyone’s grasp.

Yet our current path doesn’t exclude eventual average global warming above 6°C. In fact, our own analysis puts the likelihood at around 10 percent, and that’s for an indisputable global catastrophe. Climate change would trigger plenty of catastrophic events with temperatures rising by much less than 6°C. Many scientists would name 2°C (3.6°F) as the threshold, and we are well on our way to exceeding that, unless there is a major global course correction.

Second, the gap between our current efforts and what’s needed on climate change is enormous. We are no experts on any of the other worst-case scenarios, but there at least it seems like much is already being done.

Take nuclear terrorism. The United States alone spends many hundreds of billions of dollars each year on its military, intelligence and security services. That doesn’t stamp out the chance of terrorism. Some of the money spent may even be fueling it, and there are surely ways to approach the problem more strategically at times, but at least the overall mission is to protect the United States and its citizens.

It would be hard to argue that U.S. climate policy today benefits from anything close to this type of effort. As for mitigating pandemics, more could surely be spent on research, monitoring and rapid response, but here too it seems like needed additional efforts would plausibly amount to a small fraction of national income.

Third, climate change has firm historical precedence. There’s ample reason to believe that pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is reliving the past — the distant past, but the past nonetheless. The planet has seen today’s carbon dioxide levels before: over 3 million years ago, with sea levels some 20 meters higher than today, and camels roaming the high Arctic. There are considerable uncertainties in all of this, but there’s little reason to believe that humanity can cheat basic physics and chemistry.

Contrast the historical precedent of climate change with that of biotechnology, or rather the lack of it. The fear that bioengineered genes and genetically modified organisms will wreak havoc in the wild is a prime example. They may act like invasive species in some areas, but a global takeover seems unlikely, to say the least. Much like climate change, historical precedent can give us some guidance. But unlike climate change, that same historical precedent gives us quite a bit of comfort.

Nature itself has tried for millions of years to create countless combinations of mutated DNA and genes. The process of natural selection all but guarantees that only a tiny fraction of the very fittest permutations has survived. Genetically modified crops grow bigger and stronger and are pesticide-resistant. But they can’t outgrow natural selection entirely. None of that yet guarantees that scientists wouldn’t be able to develop permutations that could wreak havoc in the wild, but historical experience would tell us that the chance is indeed slim.

In fact, the best scientists working on biotechnology seem to be much less concerned about the dangers of “Frankenfoods” and GMOs than the general public.

The reverse holds true for climate change. The best climate scientists appear to be significantly more concerned about ultimate climate impacts than the majority of the general public and many policy makers. That alone should give us pause.

Some of these same climate scientists — knowing what they know about the science, and knowing what they know about human responses to the climate problem — seem to have moved on. And they haven’t moved on to analyzing any of the other worst-case scenarios, believing that climate isn’t all that bad. Quite the opposite: Some have moved on to looking for solutions to the climate crisis in an entirely different realm, searching for anything that could pull the planet back from the brink of a looming catastrophe. Their focus: geoengineering.

That, more than anything, should lead us to put the climate problem in its proper context. Climate is not the only “worst-case scenario” imaginable. Others, too, deserve more attention. But none of that excuses inaction on climate. And more importantly, there’s perhaps no other problem where the probability of disaster multiplied by the magnitude of disaster is as high as with climate.

That’s not a hopeful message. But no one ever said the truth tastes sweet. Where we can take comfort, though, is that there are ways, such as a putting an appropriate price on carbon, that can quickly address the climate crisis now that we’ve established it’s the issue most in need of our attention.

Published on Ensia.com on April 1st, 2015. Continue reading in Climate Shock, available at booksellers everywhere.

Errors of commission versus errors of omission

By Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman

Know what moral philosophers call the “trolley problem”? Should you push a man over the bridge to stop a trolley that would otherwise kill one or more innocent bystanders?

The moral of the story is always the same. If the tradeoff involves a one-to-one ratio, errors of commission are worse than errors of omission. Pushing one man to his death is worse than standing by and allowing the trolley to kill an innocent bystander.

Economists typically don’t take as firm a moral stance as philosophers, but they, too, draw a clear distinction between the two kinds of actions.

Economists rather dispassionately call them “Type I errors” and “Type II errors.” The first is acting when action was not warranted, actively doing something wrong: An error of commission. The second is not acting when action was warranted, or failing to actively do something right: An error of omission.

Many of us are painfully aware of that distinction. It’s one reason why we would rather stick with the default choice given to us in many situations.

Errors of commission or omission on a global level

Once you shift from the immediate and personal to the long-term and global, you multiply the potential for harm — and for confusion.

Among the many large public policy problems of our day, perhaps the most difficult to grapple with is global climate change. The problem is almost uniquely global, long-term, irreversible and uncertain.

Though the impacts of climate change will surely be severe, when and how they hit is far less sure.

Powerful, entrenched interests that are heavily invested in the status quo make it yet more difficult to formulate sensible climate policy solutions.

Add to that the moral questions around errors of commission versus omission, and implementing the right solution becomes harder still. The trolley problem, after all, teaches us that omitting action may be less bad than committing errors in acting.

Avoiding being blamed ranks highly in the minds of politicians.

But errors of commission surely cannot be ranked absolutely worse than errors of omission. Size matters, too. What if throwing the man over the bridge to stop the trolley does not just save one or two others but instead saves thousands? What about a million?

We cannot tell you where the cutoff is, just that there is one. At some point, a massive error of omission must outweigh a relatively small error of commission. That’s clearly where we are with climate change.

The science points toward action

Science is clear on the fact that what we know ought to compel us to take action now. Most everything we do not know pushes us further still, pointing to the potential of massive further losses in lives and livelihoods alike.

Given the starting point almost everywhere in the world, any step toward a price of carbon of at least $40 per ton of carbon dioxide would be a step in the right direction.

That $40 is the U.S. government’s current central estimate of the damages caused by one ton of carbon dioxide over its lifetime. Almost by definition, that number only counts what we know. The right number would almost surely be much higher.

But even at the off chance that some action will have turned out to be a step too far, it would be a rather small mistake. We may end up with an economy that is more energy efficient and less carbon intensive than it really needed to be — a small potential error of commission.

The choice is clear

Our failure to enact climate policy can no longer be likened to an error of omission. The greenhouse effect is 19th century news. It had been discovered by 1824, shown in a laboratory by 1859 and quantified by 1896.

The term “global warming” itself has been around since 1975. The basic science has been settled for decades. Using our atmosphere as a sewer for our carbon emissions is uneconomic, unethical or worse.

All seven billion of us — especially the one billion or so high emitters responsible for most of the pollution — are committing errors of commission every single day.

No single person is responsible for any single climate change-related loss of property or loss of life, but collectively we all are. That holds particularly true for elected officials, who have no excuse not to know.

Failing to act, then, is not only an error of omission but indeed an error of commission. Another term for it — “willful blindness.”

Published by The Globalist . Continue reading in Climate Shock , available at booksellers everywhere.

March 30, 2015

“Naomi Klein wants to stick it to the man. I want to stick it to CO2.″

By Jonathan Derbyshire, Prospect Magazine's The world of ideas.

Why is it so difficult to get people to worry about climate change? After all, the science is pretty unambiguous—pace the climate change “deniers”. Part of the problem, according to a new book, “Climate Shock,” by the economists Gernot Wagner and Martin L Weitzman, is that while what we know about global warming is bad enough, there are “unknown risks that may yet dwarf all else.”

Why is it so difficult to get people to worry about climate change? After all, the science is pretty unambiguous—pace the climate change “deniers”. Part of the problem, according to a new book, “Climate Shock,” by the economists Gernot Wagner and Martin L Weitzman, is that while what we know about global warming is bad enough, there are “unknown risks that may yet dwarf all else.”

Wagner, who is lead senior economist at the Environmental Defense Fund in the United States, visited London a couple of weeks ago. I caught up with him while he was here and talked to him about the difficulties of mobilising public opinion around the threats and challenges of climate change.

GW: The big problem, frankly, is speaking the truth and talking about what scientists actually know and what they don’t know, which in many ways is even scarier. Saying the latest science out loud is [often taken to be] akin to catastrophising. That’s the big conundrum: on the one hand, “climate shock” shouldn’t be all that shocking—we’ve known this for quite a while. The problem is finding a way to state the scientific facts in a way that does not turn people off immediately.

JD: So it’s partly a public relations or political challenge then?

It’s more than that. Political, certainly. But it’s also a science communications challenge.

You mentioned scientific uncertainty just now. The book is, among other things, an attempt to deal with the challenge of climate change and the policymaking challenges from an economic perspective. But it’s also, it seems to me, a work of epistemology, almost—it’s a reflection on uncertainty and the implications that uncertainty has for policymaking.

Most books are written about what we know. This book is about what we don’t know. We clearly know enough to act. We’ve known enough to act for years, decades. Now, the more we find out, the more apparent it gets that what we don’t know is in fact potentially much, more worse. Choose you favourite analogy here—Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s “black swans,” Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns”. That’s what it’s all about. The things we don’t know will most likely be the things that bite us in the back.

This is one of the things that makes climate change a public policy challenge unlike any other.

Climate change is uniquely long-term. It is uniquely global. It is uniquely irreversible and uniquely uncertain. You could probably identify other policy issues that combine two of those four factors, but none that I know of combines all four like climate change [does].

Continue reading in Prospect Magazine .

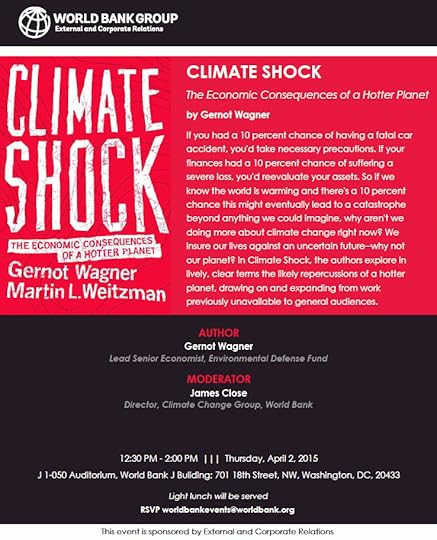

World Bank

Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet

April 2nd, 2015, 12:30 pm

World Bank

701 18th Street, NW

Washington, DC 20433

For more info and to follow the event online. Further Climate Shock book events.

Politics & Prose

Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet

April 1st, 2015, 7:00 pm

Politics & Prose

5015 Connecticut Ave. NW

Washington, DC 20008

Directions and further info. Further Climate Shock book events.

March 29, 2015

The planet won’t notice you recycle, and your vote doesn’t count

[caption id="attachment_2379" align="alignnone" width="602"]

Credit: homydesign via Shutterstock/Salon[/caption]

Credit: homydesign via Shutterstock/Salon[/caption]Your vote doesn’t count.

Put a group of economists in a room to debate the wisdom and virtue of individual action, and soon they’ll be debating the value of casting one’s vote: zero—in some strict, narrow, “economic” sense of the world.

It’s a tough pill to swallow and runs counter to every call for civic duty, but we don’t say this lightly. The chance of your one vote making the ultimate difference is so small we might as well call it zero. Some of the best research on this topic—by a team including Nate Silver of baseball statistics and, more recently, of FiveThirtyEight electoral prediction fame—put the probability of your vote making a difference in a U.S. presidential election at 1 in 60 million. And that figure includes the 2000 George W. Bush–Al Gore match-up in Florida. These are steep odds, to put it mildly. Even if your candidate were able to boost U.S. gross domestic product by ¼ percent in a given year, and we assume a very close election, your personal benefit of casting the decisive vote would still only be a tiny fraction of a penny. In other words: zero.

We can’t leave things there. It would be both rather depressing and also rather narrow-minded. Maybe statistics and economics alone aren’t the right tools with which to analyze one’s personal action. Ethics, for one, plays an important role.

Why vote

Self-declared “rational” economists may continue to shake their heads in private and joke about how voting is one of these unexplained mysteries. It’s not a mystery for the rest of us. We all know that voting is the right thing to do. Our military men and women pay with their lives for us to be able to cast that vote. It’s a sacred right. It’s the epitome of democracy. Not voting shows contempt for American— for human—values. We shouldn’t just vote. We should rock the vote. Or at least we should display a prominent sticker declaring that we have voted, thereby coaxing others into doing so.

Your personal monetary gain may be zero, but that’s beside the point. The point is to do the right thing, and voting is as simple as that gets. It doesn’t require you to take your family to a soup kitchen on Christmas morning to volunteer. You don’t need to pay extra to do it (ever since poll taxes were outlawed). Some employers even give you the day off. And you can express your opinion without having to do so publicly. You don’t have to tell anyone whom you voted for, as long as you do vote. Civic duty fulfilled.

Academics have a way of complicating things quite a bit. Here’s a shortened version of what Jason Brennan describes as “the folk theory of voting ethics”:

Each citizen has a civic duty to vote.

Any good faith vote is morally acceptable. At the very least, it is better to vote than to abstain.

It is inherently wrong to buy or sell one’s vote.

Brennan then spends 200 pages destroying that folk theorem and arrives at a more complex ethical justification for voting. He could even live with people buying and selling their vote, but any old vote won’t do. If you don’t vote for the common good over your own narrow self-interest, don’t vote at all.

In other words: Your civic duty isn’t just to vote, it’s to vote well. It’s a tough argument with which to disagree. Vote for a cause larger than yourself. Vote for those who promise more than just to further their own agenda (or yours!). Vote for those who seek to look out for society at large.

Whatever that may mean in a specific case, it clearly goes beyond the not-sure-I-should-vote-I’d-rather-watch-TV reasoning. Get up and vote; it’s the right thing to do. And don’t just vote for the sake of voting. Vote as an informed citizen. Vote well.

That means thinking through the questions we’re asking in this book, and then seriously asking yourself whether to vote for candidates who will act on climate change.

Why recycle, bike, and eat less meat

Shift gears to reducing, reusing, and recycling, the mantra of every good environmentalist. The thinking there is roughly the same as for voting. Your single act of kindness isn’t going to change the course of history. Recycling won’t stop global warming. One of us wrote an entire book titled: But Will the Planet Notice?

No, it won’t.

The math is about as clear as can be, all without having to go through Nate Silver–type reasoning to guess how likely it is that your vote could decide a U.S. presidential election. Reducing your own carbon footprint to zero is a noble gesture, but it’s less than a drop in the bucket. Quite literally: the standard U.S. bucket holds about 300,000 drops; but you are one in over 300,000,000 as an American, and you are one in seven billion as a human being.

Every little bit doesn’t always help. In the words of David MacKay analyzing the implications for the wider energy system, “if everyone does a little, we’ll achieve only a little.” So why go green at all? Because it’s the right thing to do. It’s also how we learn the values that we have to apply on a much larger scale to tackle climate change.

Recycle. Bike to work. Eat less meat. Maybe go all the way and turn vegetarian. Teach your kids to do the same, and to turn off the water while brushing their teeth. It’s good for you. It’s good for those around you. It’s the right thing to do.

But do it well. Don’t just vote. Vote well. Don’t just recycle. Recycle well.

Recycle well

If individual, inherently moral acts of environmental stewardship—like recycling—lead to better policies, sign us up. The goal, in the end, is to enact the best overall policies that will guide market forces in the right direction. So if asking one more person to recycle more is the foot in the door for their going to the polls and voting for the right policies that are in the common interest, great. Ask people to “go green” in some small way like bringing a canvas bag to the store, and they may feel a greater moral obligation to do something about larger environmental issues. Psychologists call it “self-perception theory”: see yourself as greener, vote greener.

Cue the virtuous circle of civic engagement, informed behavioral change, and all-around good things for a better planet: Voting well leads to better policies, which allow for a more enlightened citizenry; a more enlightened citizenry, in turn, leads to more people voting well. Recycling well leads to better environmental policies, which allow for a more environmentally enlightened citizenry; a more environmentally enlightened citizenry, in turn, leads to more people recycling well.

Call it the Copenhagen Theory of Change . Danes didn’t wake up one day and decide to bike to work en masse through the bitter cold of northern Europe. Nor did Copenhagen’s Lord Mayor wake up one day and decide to install a sufficient number of bike paths to get his residents out of their cars and onto bikes. Cars had dominated Copenhagen much like most other European cities for decades. It took the fuel crisis of the 1970s, increased environmentalism, and years of activism to go from “car-free Sundays” to over 50 percent of Copenhageners commuting by bike every day.

And biking isn’t unique. The Voting Rights Act wasn’t passed overnight. It took years of all sorts of action—from the early sit-ins to the Selma marches. The U.S. environmental movement, which sparked the “environmental decade” of the 1970s, followed a similar path. Years of self-reinforcing activism eventually led to the necessary legislative changes, and the debate didn’t end there.

Time is the all-important factor. We once had decades to turn the climate ship around. Not anymore. That makes it all the more important to get our theory of change right. It’s also where we return to our recurring theme of tradeoffs, this time as it pertains to recycling well.

Economists deem the existence of trade-offs to be self-evident common sense. Psychologists add another twist to it, turning the effects of “see yourself as greener, vote greener” on its head. Call it the “crowding-out bias.” The threat of climate change motivates people to act—but only up to a point. In the extreme version of this effect, the “single-action bias,” people may do only one thing, like recycle, or put a solar panel on their roof, or buy a “green” product. This doesn’t necessarily mean that anyone, in fact, believes that one step is indeed enough to stop climate change, but that one step may be enough to assuage their worries and lead them to move on. Yes, the climate is changing, but women are still dying in childbirth. There are other problems to worry about, too, and now I’ve done my part for climate change.

Economists are instinctively more comfortable with this crowding-out bias view of the world than the one supporting the self-perception theory, a.k.a. the Copenhagen Theory of Change. After all, trade-offs often lead people to substitute one action for another. That’s particularly troubling when people substitute single, individual actions—like recycling—for larger policy actions—like voting. This phenomenon has been surprisingly poorly studied so far.

We know quite a bit about the mechanisms from collective action back down to individual ones. Setting the right incentives—paying people to do certain things— sometimes crowds out virtuous behavior. Pay people to donate blood, and watch blood donations go down, at least among women. Men seem to have no qualms about being paid for their donations, and women, too, increase their donations once again when the money is given to charity rather than paid out to them.

We also know a bit about substitution among individual actions. Ask people to voluntarily pay more for “green electricity” and watch some increase their electricity consumption as a result.

Both of these mechanisms support the crowding-out bias view of the world, where one green deed doesn’t necessarily beget another but may indeed be a hindrance in light of trade-offs in people’s everyday behavior. However, we know little about whether the crowding-out bias does, in fact, extend from individual to collective action.

No one wants the crowding-out bias to dominate. It’s something to avoid and overcome. If you catch yourself recycling that paper cup and thinking you’ve solved global warming for the day, think again. If you catch yourself buying those voluntary carbon offsets for the cross-country flight, feeling better about flying, and as a result doing more of it, that’s not quite in the spirit of the exercise either. “The hotel changes my towels only when I throw them on the floor and the airline lets me spend $20 extra to offset my carbon pollution? Eco-vacation, here I come!”

None of that is all that far-fetched, even for the most committed of environmentalists. You can’t do it all. Plenty of environmentalists who recycle, refuse meat, don’t drive, and generally try to do it all the green way still commit various other, often more significant carbon sins. Flying is a prime example.

Continue reading in Salon.

Excerpted from “Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet” by Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman.

March 27, 2015

Prospect Magazine Q&A with Jonathan Derbyshire

By Jonathan Derbyshire, Prospect Magazine‘s The world of ideas.

Why is it so difficult to get people to worry about climate change? After all, the science is pretty unambiguous—pace the climate change “deniers”. Part of the problem, according to a new book, “Climate Shock,” by the economists Gernot Wagner and Martin L Weitzman, is that while what we know about global warming is bad enough, there are “unknown risks that may yet dwarf all else.”

Why is it so difficult to get people to worry about climate change? After all, the science is pretty unambiguous—pace the climate change “deniers”. Part of the problem, according to a new book, “Climate Shock,” by the economists Gernot Wagner and Martin L Weitzman, is that while what we know about global warming is bad enough, there are “unknown risks that may yet dwarf all else.”

Wagner, who is lead senior economist at the Environmental Defense Fund in the United States, visited London a couple of weeks ago. I caught up with him while he was here and talked to him about the difficulties of mobilising public opinion around the threats and challenges of climate change.

GW: The big problem, frankly, is speaking the truth and talking about what scientists actually know and what they don’t know, which in many ways is even scarier. Saying the latest science out loud is [often taken to be] akin to catastrophising. That’s the big conundrum: on the one hand, “climate shock” shouldn’t be all that shocking—we’ve known this for quite a while. The problem is finding a way to state the scientific facts in a way that does not turn people off immediately.

JD: So it’s partly a public relations or political challenge then?

It’s more than that. Political, certainly. But it’s also a science communications challenge.

You mentioned scientific uncertainty just now. The book is, among other things, an attempt to deal with the challenge of climate change and the policymaking challenges from an economic perspective. But it’s also, it seems to me, a work of epistemology, almost—it’s a reflection on uncertainty and the implications that uncertainty has for policymaking.

Most books are written about what we know. This book is about what we don’t know. We clearly know enough to act. We’ve known enough to act for years, decades. Now, the more we find out, the more apparent it gets that what we don’t know is in fact potentially much, more worse. Choose you favourite analogy here—Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s “black swans,” Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns”. That’s what it’s all about. The things we don’t know will most likely be the things that bite us in the back.

This is one of the things that makes climate change a public policy challenge unlike any other.

Climate change is uniquely long-term. It is uniquely global. It is uniquely irreversible and uniquely uncertain. You could probably identify other policy issues that combine two of those four factors, but none that I know of combines all four like climate change [does].

Continue reading in Prospect Magazine .

March 20, 2015

If you can’t say it in English, don’t bother

Published by Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs.

Tell us about ‘Climate Shock’.

Most books are about what we know. This book is about what we don’t.

When it comes to climate change, there is plenty we do know. We know that it’s a problem and that it demands sensible action now.

What we don’t know about climate change makes it a much bigger problem than what we commonly assume.

One way of looking at it is via the so-called ‘social cost of carbon.’ What does one ton of carbon dioxide pollution cost us? The U.S. government’s central—and I’d add, conservative—estimate is $40 per ton of carbon dioxide. Step one, then, is to put a price on carbon of at least as much.

But the emphasis needs to be on “at least as much.” What we don’t know pushes the number in one and only one direction. The true number is likely much higher, and by ignoring that probability we are taking a huge gamble, and betting the one planet we’ve got.

Awareness of this issue is increasing, and more people seem to be giving climate change more pressing attention. Do you think we’re at least moving in the right direction?

Yes, we are. Awareness clearly is increasing. There have been plenty of policies put in place that are in fact starting to move in the right direction. So, yes, I’m optimistic.

But, much, much more needs to be done. We are at the very beginning stages of where we need to go.

When you look at the $40 per ton of carbon dioxide, some places are indeed getting close. The problem, once again, of course, is that 40 might be seriously underestimating the true cost.

With that in mind, what do you want people to take away from this book?

Well, as a teacher, one implication is clear: Be curious about the world and work to learn more about the things we don’t yet know.

But we also need to realize that there are some things we may never know, at least not in any of our lifetimes. We may never have the full, ‘right’ answer. There’ll always be uncertainties left.

So in order to act sensibly on climate change, we have to deal with these uncertainties, these risks. That calls for the same kind of thinking that economists, businesses, and Wall Street use: in the end, it’s all about risk management.

You mentioned teaching; how long have you been at SIPA? How would you characterize your experience?

I’ve been at SIPA for five years, where I teach Economics of Energy, a broad survey class. It’s a class very much in line with the ideas of Climate Shock: substantively, energy and climate are two sides of the same coin.

And in terms of approach—both to this book, and in the class—if you can’t say it in English, don’t bother. There’s plenty of research that went into the 100-or-so pages of end notes in the book. But the main text is without equations, without jargon.

Same in the class: it’s an economics class, but all the assignments are strictly focused on writing 1,000-word essays. Do the research, understand the serious work economists do to analyze a particular question, but once you write it up, put it in plain English, with two feet in the real world. It’s a very good way of keeping you honest.

This interview, conducted by Tamara El Waylly MIA ’15, has been edited and condensed.

Columbia University

Climate Shock: A Conversation with Gernot Wagner

March 30th, 2015, 6:00 pm - 7:30 pm

International Affairs Building, Room 1512

420 West 118th Street

New York, NY 10027

Please join the Center on Global Energy Policy for a presentation and discussion with Gernot Wagner, lead senior economist at Environmental Defense Fund, adjunct associate professor at Columbia SIPA, and research associate at Harvard Kennedy School. Mr. Wagner will discuss Climate Shock, the new book he co-authored with Martin L. Weitzman which explores the known and unknown risks of a hotter planet and the economic forces that will shape future climate change policies. Center Fellow Joe Aldy will moderate a discussion.

Please register via Columbia's Center on Global Energy Policy. Further Climate Shock book events.

Gernot Wagner's Blog

- Gernot Wagner's profile

- 22 followers