Gernot Wagner's Blog, page 2

July 17, 2015

What we know — and what we don’t — about global warming

By Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman:

Two quick questions:

Do you think climate change is an urgent problem?

Do you think getting the world off fossil fuels is difficult?

This is how our book “Climate Shock” begins.

In fact, it’s not our quiz. Robert Socolow from Princeton has posed versions of these questions for a while. The result is usually the same: most people answer “Yes” to one or the other question, but not to both. You are either one or the other: an “environmentalist” or perhaps, a self-described “realist.”

Such answers are somewhat understandable, especially when looking at the polarized politics around global warming. They are also both wrong. Climate change is incredibly urgent and difficult to solve.

What we know is bad

Last time concentrations of carbon dioxide were as high as they are today — 400 parts per million — we had sea levels that were between 20 to at least 66 feet higher than today.

It doesn’t take much to imagine what another foot or two will do. And sea levels at least 20 feet above where they are today? That’s largely outside our imagination.

This won’t happen overnight. Sea levels will rise over decades, centuries and perhaps even millennia. That’s precisely what makes climate change such an immense challenge. It’s more long-term, more global, more irreversible and also more uncertain than most other problems facing us. The combination of all of these things make climate change uniquely problematic.

What we don’t know makes it potentially much worse

Climate change is beset with deep-seated uncertainties on top of deep-seated uncertainties on top of still more deep-seated uncertainties. And that’s just if you consider the links between carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere, eventual temperature increases and economic damages.

Increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide are bound to lead to an increase in temperatures. That much is clear. The question is how much.

The parameter that gives us the answer to this all-important question is “climate sensitivity.” That describes what happens to eventual global average temperatures as concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere double. Nailing down that parameter has been an epic challenge.

Ever since the late 1970s, we’ve had estimates hovering at around 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit. In fact, the “likely” range is around 5.5 degrees plus-minus almost three degrees.

What’s worrisome here is that since the late 1970s that range hasn’t narrowed. In the past 35 years, we’ve seen dramatic improvements in many aspects of climate science, but the all-important link between concentrations and temperatures is still the same.

What’s more worrisome still is that we can’t be sure we won’t end up outside the range. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change calls the range “likely.” So by definition, anything outside it is “unlikely.” But that doesn’t make it zero probability.

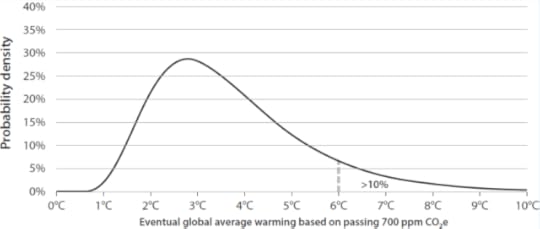

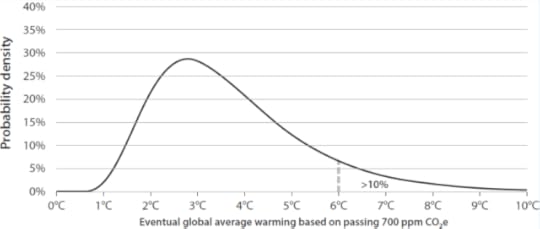

In fact, we have around a 10 percent chance that eventual global average temperature increases will exceed 11 degrees Fahrenheit, given where the world is heading in terms of carbon dioxide emissions. That’s huge, to put it mildly, both in probability and in temperature increases.

Climate Shock graph. There’s at least about a 10 percent chance of global average temperatures increasing 11 degrees Fahrenheit or more. Source: Climate Shock (Princeton 2015), reprinted with permission.

We take out car, fire and property insurances for much lower probabilities. Here we are talking about the whole planet, and we haven’t shown willingness to insure ourselves. Meanwhile, we can, in fact, look at 11 degrees Fahrenheit and liken it to the planet ‘burning’. Think of it as your body temperature: 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit is normal. Anything above 99.5 degrees Fahrenheit is a fever. Above 104 degrees Fahrenheit is life-threatening. Above 109.4 degrees Fahrenheit and you are dead or at least unconscious.

In planetary dimensions, warming of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit is so bad as to have been enshrined as a political threshold not to be crossed. Going to 11 degrees Fahrenheit is so far outside the realm of anything imaginable, we can simply call it a planetary catastrophe. It would surely be a planet none of us would recognize. Go back to sea levels somewhere between 20 and at least 66 feet higher than today, at today’s concentrations of carbon dioxide. How much worse can it get?

Do we know for sure that we are facing a 1-in-10 chance unless the world changes its course? No, we don’t, and we can’t. One thing though is clear: because the extreme downside is so threatening, the burden of proof ought to be on those who argue that these extreme scenarios don’t matter and that any possible damages are low. So how then can we guide policy with all this talk about “not knowing”?

What’s your number?

We can begin to insure ourselves from climate change by pricing emissions. How? By charging at least $40 per ton of carbon dioxide pollution. That’s the U.S. government’s current value and central estimate of the costs caused by one ton of carbon dioxide pollution emitted today.

We know that $40 per ton is an imperfect number. We are pretty sure it’s an underestimate; we are confident it’s not an overestimate. But it’s also all we have. (And it’s a lot higher than the prevailing price in most places that do have a carbon price right now—from California to the European Union. The sole exception is Sweden, where the price is upward of $130. And even there, key sectors are exempt.)

How then do we decide on the proper climate policy? The answer is more complex than our rough cost-benefit analysis suggests. Pricing carbon at $40 a ton is a start, but it’s only that. Any cost-benefit analysis relies on a number of assumptions — perhaps too many — to come up with one single dollar estimate based on one representative model. And with something as large and uncertain as climate change, such assumptions are intrinsically flawed.

Since we know that the extreme possibilities can dominate the final outcome, the decision criterion ought to focus on avoiding these kinds of catastrophic damages in the first place. Some call this a “precautionary principle”— better to be safe than sorry. Others call it a variant of “Pascal’s Wager” — why should we risk it if the punishment is eternal damnation? We call it a “Dismal Dilemma.” While extremes can dominate the analysis, how can we know the relevant probabilities of rare extreme scenarios that we have not previously observed and whose dynamics we only crudely understand at best? The true numbers are largely unknown and may simply be unknowable.

Planetary risk management

In the end, this is all about risk management—existential risk management. Precaution is a prudent stance when uncertainties about catastrophic risks are as dominant as they are here. Cost-benefit analysis is important, but it alone may be inadequate, simply because of the fuzziness involved with analyzing high-temperature impacts.

Climate change belongs to a rare category of situations where it’s extraordinarily difficult to put meaningful boundaries on the extent of possible planetary damages. Focusing on getting precise estimates of the damages associated with eventual global average warming of 7, 9 or 11 degrees Fahrenheit misses the point.

The appropriate price on carbon dioxide is one that will make us comfortable that the world will never heat up another 11 degrees and that we won’t see its accompanying catastrophes. Never, of course, is a strong word, since even today’s atmospheric concentrations have a small chance of causing eventual extreme temperature rise.

One thing we know for sure is that a greater than 10 percent chance of the earth’s eventual warming of 11 degrees Fahrenheit or more — the end of the human adventure on this planet as we now know it — is too high. And that’s the path the planet is on at the moment. With the immense longevity of atmospheric carbon dioxide, continuing to “wait and see” would amount to nothing else than willful blindness.

First published by PBS NewsHour's Making Sen$e with Paul Solman. The accompanying NewsHour report aired on July 16, 2015.

What we know — and what we don’t — about global warming

Two quick questions:

Do you think climate change is an urgent problem?

Do you think getting the world off fossil fuels is difficult?

This is how our book “Climate Shock” begins.

In fact, it’s not our quiz. Robert Socolow from Princeton has posed versions of these questions for a while. The result is usually the same: most people answer “Yes” to one or the other question, but not to both. You are either one or the other: an “environmentalist” or perhaps, a self-described “realist.”

Such answers are somewhat understandable, especially when looking at the polarized politics around global warming. They are also both wrong. Climate change is incredibly urgent and difficult to solve.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VMR-...

What we know is bad

Last time concentrations of carbon dioxide were as high as they are today — 400 parts per million — we had sea levels that were between 20 to at least 66 feet higher than today.

It doesn’t take much to imagine what another foot or two will do. And sea levels at least 20 feet above where they are today? That’s largely outside our imagination.

This won’t happen overnight. Sea levels will rise over decades, centuries and perhaps even millennia. That’s precisely what makes climate change such an immense challenge. It’s more long-term, more global, more irreversible and also more uncertain than most other problems facing us. The combination of all of these things make climate change uniquely problematic.

What we don’t know makes it potentially much worse

Climate change is beset with deep-seated uncertainties on top of deep-seated uncertainties on top of still more deep-seated uncertainties. And that’s just if you consider the links between carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere, eventual temperature increases and economic damages.

Increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide are bound to lead to an increase in temperatures. That much is clear. The question is how much.

The parameter that gives us the answer to this all-important question is “climate sensitivity.” That describes what happens to eventual global average temperatures as concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere double. Nailing down that parameter has been an epic challenge.

Ever since the late 1970s, we’ve had estimates hovering at around 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit. In fact, the “likely” range is around 5.5 degrees plus-minus almost three degrees.

What’s worrisome here is that since the late 1970s that range hasn’t narrowed. In the past 35 years, we’ve seen dramatic improvements in many aspects of climate science, but the all-important link between concentrations and temperatures is still the same.

What’s more worrisome still is that we can’t be sure we won’t end up outside the range. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change calls the range “likely.” So by definition, anything outside it is “unlikely.” But that doesn’t make it zero probability.

In fact, we have around a 10 percent chance that eventual global average temperature increases will exceed 11 degrees Fahrenheit, given where the world is heading in terms of carbon dioxide emissions. That’s huge, to put it mildly, both in probability and in temperature increases.

[caption id="attachment_2538" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Climate Shock graph. There’s at least about a 10 percent chance of global average temperatures increasing 11 degrees Fahrenheit or more. Source: Climate Shock (Princeton 2015), reprinted with permission.[/caption]

Climate Shock graph. There’s at least about a 10 percent chance of global average temperatures increasing 11 degrees Fahrenheit or more. Source: Climate Shock (Princeton 2015), reprinted with permission.[/caption]We take out car, fire and property insurances for much lower probabilities. Here we are talking about the whole planet, and we haven’t shown willingness to insure ourselves. Meanwhile, we can, in fact, look at 11 degrees Fahrenheit and liken it to the planet ‘burning’. Think of it as your body temperature: 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit is normal. Anything above 99.5 degrees Fahrenheit is a fever. Above 104 degrees Fahrenheit is life-threatening. Above 109.4 degrees Fahrenheit and you are dead or at least unconscious.

In planetary dimensions, warming of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit is so bad as to have been enshrined as a political threshold not to be crossed. Going to 11 degrees Fahrenheit is so far outside the realm of anything imaginable, we can simply call it a planetary catastrophe. It would surely be a planet none of us would recognize. Go back to sea levels somewhere between 20 and at least 66 feet higher than today, at today’s concentrations of carbon dioxide. How much worse can it get?

Do we know for sure that we are facing a 1-in-10 chance unless the world changes its course? No, we don’t, and we can’t. One thing though is clear: because the extreme downside is so threatening, the burden of proof ought to be on those who argue that these extreme scenarios don’t matter and that any possible damages are low. So how then can we guide policy with all this talk about “not knowing”?

What’s your number?

We can begin to insure ourselves from climate change by pricing emissions. How? By charging at least $40 per ton of carbon dioxide pollution. That’s the U.S. government’s current value and central estimate of the costs caused by one ton of carbon dioxide pollution emitted today.

We know that $40 per ton is an imperfect number. We are pretty sure it’s an underestimate; we are confident it’s not an overestimate. But it’s also all we have. (And it’s a lot higher than the prevailing price in most places that do have a carbon price right now—from California to the European Union. The sole exception is Sweden, where the price is upward of $130. And even there, key sectors are exempt.)

How then do we decide on the proper climate policy? The answer is more complex than our rough cost-benefit analysis suggests. Pricing carbon at $40 a ton is a start, but it’s only that. Any cost-benefit analysis relies on a number of assumptions — perhaps too many — to come up with one single dollar estimate based on one representative model. And with something as large and uncertain as climate change, such assumptions are intrinsically flawed.

Since we know that the extreme possibilities can dominate the final outcome, the decision criterion ought to focus on avoiding these kinds of catastrophic damages in the first place. Some call this a “precautionary principle”— better to be safe than sorry. Others call it a variant of “Pascal’s Wager” — why should we risk it if the punishment is eternal damnation? We call it a “Dismal Dilemma.” While extremes can dominate the analysis, how can we know the relevant probabilities of rare extreme scenarios that we have not previously observed and whose dynamics we only crudely understand at best? The true numbers are largely unknown and may simply be unknowable.

Planetary risk management

In the end, this is all about risk management—existential risk management. Precaution is a prudent stance when uncertainties about catastrophic risks are as dominant as they are here. Cost-benefit analysis is important, but it alone may be inadequate, simply because of the fuzziness involved with analyzing high-temperature impacts.

Climate change belongs to a rare category of situations where it’s extraordinarily difficult to put meaningful boundaries on the extent of possible planetary damages. Focusing on getting precise estimates of the damages associated with eventual global average warming of 7, 9 or 11 degrees Fahrenheit misses the point.

The appropriate price on carbon dioxide is one that will make us comfortable that the world will never heat up another 11 degrees and that we won’t see its accompanying catastrophes. Never, of course, is a strong word, since even today’s atmospheric concentrations have a small chance of causing eventual extreme temperature rise.

One thing we know for sure is that a greater than 10 percent chance of the earth’s eventual warming of 11 degrees Fahrenheit or more — the end of the human adventure on this planet as we now know it — is too high. And that’s the path the planet is on at the moment. With the immense longevity of atmospheric carbon dioxide, continuing to “wait and see” would amount to nothing else than willful blindness.

First published by PBS NewsHour's Making Sen$e with Paul Solman. The accompanying NewsHour report aired on July 16, 2015.

PBS NewsHour: The economic options for combatting climate change

As greenhouse gases accumulate and global temperatures slowly rise, what can we do to insure against the catastrophes of climate change? Economics correspondent Paul Solman talks to the authors of Climate Shock.

July 16, 2015

PBS NewsHour

As greenhouse gases accumulate and global temperatures slowly rise, what can we do to insure against the catastrophes of climate change? Economics correspondent Paul Solman talks to the authors of Climate Shock .

June 15, 2015

Pluses and Minuses of a Carbon Tax

To the Editor:

A price on carbon is an essential tool in reducing climate pollution, but don’t give short shrift to a proven approach: emissions trading.

Well-designed pollution markets helped cut acid rain in the United States at a fraction of the predicted cost. Similar markets are working today to cut carbon pollution in California, seven Chinese cities and provinces, and other countries and regions home to nearly a billion people in all.

Even the European Union system you criticize has successfully cut emissions, and given the E.U. confidence to adopt a more stringent target.

The goal of climate policy is not simply to price pollution; it is to reduce it. Either a tax or a cap, if well designed, can achieve it. So let’s move beyond this debate and focus on the real issue: the need for ambitious action, at home and abroad, to put the world on a path to a secure and stable climate.

Nathaniel O. Keohane

Gernot Wagner

New York

The writers are, respectively, vice president for international climate and lead senior economist at the Environmental Defense Fund.

Published as Letter to the Editor in the New York Times on June 15th, 2015.

June 2, 2015

When dealing with global warming, the size of the risk matters

Shortly after September 11, 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney gave us what has since become known as the One Percent Doctrine: “If there’s a 1% chance that Pakistani scientists are helping al-Qaeda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response.”

It inspired at least one book, one war, and many a comparison to the "precautionary principle" familiar to most environmentalists. It’s also wrong.

One percent isn’t certainty. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t take the threat seriously, or that the precautionary principle is wrong, per se. We should, and it isn’t.

Probabilities matter.

Take strangelets as one extreme. They are particles with the potential to trigger a chain reaction that would reduce the Earth to a dense ball of strange matter before it explodes, all in fractions of a second.

That’s a high-impact event if there ever was one. It’s also low-probability. Really low probability.

At the upper bound, scientists put the chance of this occurring at somewhere between 0.002% and 0.0000000002% per year, and that’s a generous upper bound.

That’s not nothing, but it’s pretty close. Should we be spending more on avoiding their creation, or figuring out if they’re even theoretically possible in the first place? Sure. Should we weigh the potential costs against the social benefit that heavy-ion colliders at CERN and Brookhaven provide? Absolutely.

Should we “treat it as a certainty” that CERN or Brookhaven are going to cause planetary annihilation? Definitely not.

Move from strangelets to asteroids, and from a worst-case scenario with the highest imaginable impact, but a very low probability, to one with significantly higher probability, but arguably much lower impact.

Asteroids come in all shapes and sizes. There’s the 20-meter wide one that unexpectedly exploded above the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in 2013, injuring mored than 1,400 people. And then there are 10-kilometer, civilization-ending asteroids.

Size matters.

No one would ask for more 20-meter asteroids, but they’re not going to change life on Earth as we know it. We’d expect a 10-kilometer asteroid, of the type that likely killed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, once every 50-100 million years. (And no, that does not mean we are ‘due’ for one. That’s an entirely different statistical fallacy.)

Luckily, asteroids are a surmountable problem. Given $2 to $3 billion and 10 years, a National Academy study estimates that we could test an actual asteroid-deflection technology. It’s not quite as exciting as Bruce Willis in Armageddon, but a nuclear standoff collision is indeed one of the options frequently discussed in this context.

That’s the cost side of the ledger. The benefits for a sufficiently large asteroid would include not destroying civilization. So yes, let’s invest the money. Period.

Somewhere between strangelets and asteroids rests another high-impact event. Unchecked climate change is bound to have enormous consequences for the planet and humans alike. That much we know.

What we don’t know — at least not with certainty — could make things even worse. The last time concentrations of carbon dioxide stood where they are today, sea levels were up to 20 meters higher than today. Camels lived in Canada. Meanwhile global average surface temperatures were only 1 to 2.5 degrees Celsius (1.8 to 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit) above today's levels.

Now imagine what the world would like with temperature of 6 degrees Celsius (11 degrees Fahrenheit) higher. There’s no other way of putting it than to suggest this would be hell on Earth.

And based on a number of conservative assumptions, my co-author Martin L. Weitzman and I calculate in Climate Shock that there might well be a 10% chance of an eventual temperature increase of this magnitude happening without a major course correction.

That’s both high-impact and high-probability.

Mr. Cheney was wrong in equating 1% to certainty. But he would have been just as wrong if he had said: "One percent is basically zero. We should just cross our fingers and hope that luck is on our side."

So what to do? In short, risk management.

We insure our homes against fires and floods, our families against loss of life, and we should insure our planet against the risk of global catastrophe. To do so, we need to act — rationally, deliberately, and soon. Our insurance premium: put a price on carbon.

Instead of pricing carbon, governments right now even pay businesses and individuals to pump more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere due to various energy subsidies, increasing the risk of a global catastrophe. This is crazy and shortsighted, and the opposite of good risk management.

All of that is based on pretty much the only law we have in economics, the Law of Demand: price goes up, demand goes down.

It works beautifully, because incentives matter.

Gernot Wagner serves as lead senior economist at the Environmental Defense Fund and is co-author, with Harvard’s Martin Weitzman, of Climate Shock (Princeton, March 2015). This op-ed first appeared on Mashable.com.

May 31, 2015

When dealing with global warming, the size of the risk matters

Shortly after September 11, 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney gave us what has since become known as the One Percent Doctrine: “If there’s a 1% chance that Pakistani scientists are helping al-Qaeda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response.”

It inspired at least one book, one war, and many a comparison to the “precautionary principle” familiar to most environmentalists. It’s also wrong.

One percent isn’t certainty. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t take the threat seriously, or that the precautionary principle is wrong, per se. We should, and it isn’t.

Probabilities matter.

Take strangelets as one extreme. They are particles with the potential to trigger a chain reaction that would reduce the Earth to a dense ball of strange matter before it explodes, all in fractions of a second.

That’s a high-impact event if there ever was one. It’s also low-probability. Really low probability.

At the upper bound, scientists put the chance of this occurring at somewhere between 0.002% and 0.0000000002% per year, and that’s a generous upper bound.

That’s not nothing, but it’s pretty close. Should we be spending more on avoiding their creation, or figuring out if they’re even theoretically possible in the first place? Sure. Should we weigh the potential costs against the social benefit that heavy-ion colliders at CERN and Brookhaven provide? Absolutely.

Should we “treat it as a certainty” that CERN or Brookhaven are going to cause planetary annihilation? Definitely not.

Move from strangelets to asteroids, and from a worst-case scenario with the highest imaginable impact, but a very low probability, to one with significantly higher probability, but arguably much lower impact.

Asteroids come in all shapes and sizes. There’s the 20-meter wide one that unexpectedly exploded above the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in 2013, injuring mored than 1,400 people. And then there are 10-kilometer, civilization-ending asteroids.

Size matters.

No one would ask for more 20-meter asteroids, but they’re not going to change life on Earth as we know it. We’d expect a 10-kilometer asteroid, of the type that likely killed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, once every 50-100 million years. (And no, that does not mean we are ‘due’ for one. That’s an entirely different statistical fallacy.)

Luckily, asteroids are a surmountable problem. Given $2 to $3 billion and 10 years, a National Academy study estimates that we could test an actual asteroid-deflection technology. It’s not quite as exciting as Bruce Willis in Armageddon, but a nuclear standoff collision is indeed one of the options frequently discussed in this context.

That’s the cost side of the ledger. The benefits for a sufficiently large asteroid would include not destroying civilization. So yes, let’s invest the money. Period.

Somewhere between strangelets and asteroids rests another high-impact event. Unchecked climate change is bound to have enormous consequences for the planet and humans alike. That much we know.

What we don’t know — at least not with certainty — could make things even worse. The last time concentrations of carbon dioxide stood where they are today, sea levels were up to 20 meters higher than today. Camels lived in Canada. Meanwhile global average surface temperatures were only 1 to 2.5 degrees Celsius (1.8 to 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit) above today’s levels.

Now imagine what the world would like with temperature of 6 degrees Celsius (11 degrees Fahrenheit) higher. There’s no other way of putting it than to suggest this would be hell on Earth.

And based on a number of conservative assumptions, my co-author Martin L. Weitzman and I calculate in Climate Shock that there might well be a 10% chance of an eventual temperature increase of this magnitude happening without a major course correction.

That’s both high-impact and high-probability.

Mr. Cheney was wrong in equating 1% to certainty. But he would have been just as wrong if he had said: “One percent is basically zero. We should just cross our fingers and hope that luck is on our side.”

So what to do? In short, risk management.

We insure our homes against fires and floods, our families against loss of life, and we should insure our planet against the risk of global catastrophe. To do so, we need to act — rationally, deliberately, and soon. Our insurance premium: put a price on carbon.

Instead of pricing carbon, governments right now even pay businesses and individuals to pump more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere due to various energy subsidies, increasing the risk of a global catastrophe. This is crazy and shortsighted, and the opposite of good risk management.

All of that is based on pretty much the only law we have in economics, the Law of Demand: price goes up, demand goes down.

It works beautifully, because incentives matter.

Gernot Wagner serves as lead senior economist at the Environmental Defense Fund and is co-author, with Harvard’s Martin Weitzman, of Climate Shock (Princeton, March 2015). This op-ed first appeared on Mashable.com.

May 24, 2015

Climate Change: Like an Asteroid

By Gernot Wagner and Martin L. Weitzman

If a civilization-as-we-know-it-altering asteroid were hurtling toward Earth, scheduled to hit a decade hence, and it had, say, a 5% chance of striking the planet, we would surely pull out all the stops to try to deflect its path.

If we knew that same asteroid were hurtling toward Earth a century hence, we may spend a few more years arguing about the precise course of action.

Clear and present danger

But here’s what we wouldn’t do: We wouldn’t say that we should be able to solve the problem in at most a decade, so we can just sit back and relax for another 90 years.

Nor would we try to bank on the fact that technologies will be that much better in 90 years, so we can probably do nothing for 91 or 92 years and we’d still be fine.

We’d act – and soon. Never mind that technologies will be getting better in the next 90 years. Never mind, either, that we may find out more about the asteroid’s precise path over the next 90 years that may be able to tell us that the chance of it hitting Earth is “only” 4% rather than the 5% we had assumed all along.

That last point — increased certainty around the final impacts — is precisely where climate change has proven so vexing. Our estimate of the range of climate sensitivity — what will happen to temperatures as concentrations in the atmosphere double — isn’t any more precise today than it was over three decades ago.

And the chance of eventual climate catastrophe isn’t 5%. Our own calculation based on IEA projections shows that it’s likely closer to 10% or even more.

Dealing with uncertainty responsibly

Climate change is beset with deep-seated uncertainties. They prevent us from simply translating temperature changes into economic damages.

One thing is clear, though: Because the extreme downside is so threatening, the burden of proof ought to be on those who argue that fat tails don’t matter, that possible damages are low and that discount rates ought to be high.

As little as we know about many of these uncertainties, we do know that the chance of eventual catastrophic warming of an additional 6°C (11°F) or more isn’t zero. In fact, it’s slightly greater than around 10%, under our conservative calibration.

Where does all of that leave us?

If the question is what single number to use as the optimal price of each ton of carbon dioxide pollution today, the answer should be at least $40 per ton of carbon dioxide, the U.S. government’s current value.

We know that number is imperfect. We are pretty sure it’s an underestimate. We are confident it’s not an overestimate. It’s also all we have.

And it’s a lot higher than the prevailing price in most places that do have a carbon price right now — from California to the European Union. The sole exception is Sweden, where the price is upward of $150. And even there, key industrial sectors are exempt.

Any benefit-cost analysis relies on a number of assumptions — perhaps too many — to truly come up with a single dollar estimate based on one representative model of something as large and uncertain as climate change.

A precautionary principle?

Since we know that fat tails can dominate the final outcome, the decision criterion ought to focus on avoiding the possibility of these kinds of catastrophic damages in the first place.

Some call it a “precautionary principle” — better safe than sorry. Others call it a variant of “Pascal’s Wager” — why risk it, if the punishment is eternal damnation? We call it a “Dismal Dilemma.”

In the end, it’s risk management — existential risk management. And it comes with an ethical component. Precaution is a prudent stance when uncertainties about catastrophic risks are as dominant as they are here. Benefit-cost analysis is important, but it alone may be inadequate, simply because of the fuzziness involved with analyzing high-temperature impacts.

With the immense longevity of atmospheric carbon dioxide, “wait and see” would amount to nothing other than willful blindness.

Published by The Globalist . Continue reading in Climate Shock , available at booksellers everywhere.

May 18, 2015

Association of Environmental and Resource Economists

Session chair and presenter: “International environmental agreements,” Friday, 5 June 2015, 3:15 – 4:45 p.m.

Presentation of “India in the Coming Climate G2?”, joint paper with Jonathan Camuzeaux and Thomas Sterner.

May 8, 2015

Houston Museum of Natural Science

HMNS Distinguished Lecture

“Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet”

Gernot Wagner, Ph.D., Environmental Defense Fund

Tuesday, May 12, 2015, 6:30 p.m.

Demonstrating that climate change can and needs to be dealt with, and what could happen if we don’t. Economist Dr. Gernot Wagner of the Environmental Defense Fund will give an authoritative call to arms for tackling the defining environmental and public policy issue of our time. Wagner will present the likely repercussions of a hotter planet, drawing and expanding from work previously unavailable to the general public. He will show how economic forces along with sensible climate policies can help prevent a catastrophic future. A book signing of Wagner’s new book Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet will follow the lecture.

Purchase tickets for $18, $12 for members. Further Climate Shock book events.

Gernot Wagner's Blog

- Gernot Wagner's profile

- 22 followers