Gernot Wagner's Blog, page 20

September 9, 2011

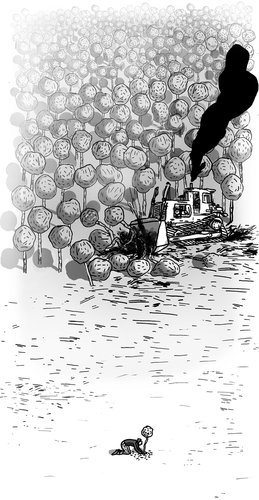

Planetary socialism

Yesterday's New York Times published my op-ed under the somewhat provocative heading "Going Green but Getting Nowhere." The point, of course, is not to give up, but instead to look for policy solutions that channel market forces in the right direction. Not because the market should be king, but because it all too often is.

Yesterday's New York Times published my op-ed under the somewhat provocative heading "Going Green but Getting Nowhere." The point, of course, is not to give up, but instead to look for policy solutions that channel market forces in the right direction. Not because the market should be king, but because it all too often is.

One of the key figures in it is the cost of $20 per ton of carbon dioxide. That comes from an immensely important appendix to an obscure government document. Table 1 summarizes the results of painstaking research, trying to tally the full cost of carbon pollution in the atmosphere. (The exact number is $21.4, of course with lots of uncertainties around it.)

That number is a consensus estimate of sorts. As such, it ignores several important factors that haven't yet found their way into standard models like the risks from low-probability, high-impact events—the truly scary climate scenarios that typically dwarf all else once included. (By one estimate, the number could be as high as $900 a ton.)

The point, of course, is that in the United States right now, carbon has a price of close to $0. That's the price each of us pays individually for the tons we emit, while society pays the full $20 or more. The term of art often used to describe the cost to society is "social cost of carbon." I prefer "socialized cost."

That's what it is: privatized benefits, socialized costs. It's what caused the financial crisis, and it's what's causing the planetary crisis as well.

It's also the sole origin of the phrase "planetary socialism."

Amazingly, some of the most thoughtful responses I received in reaction to my op-ed seemed to be treatises on the benefits of socialism. So just to be clear: Yes, I realize that "socialism" has many other meanings. Yes, I do like single-payer healthcare systems as much as the next Austro-American who has experienced both. No, I don't have anything against the exemplary Scandinavians who always seem to be doing the right thing, even if it's not in their self-interest.

Sweden, it turns out, has had a carbon tax for quite a while—one that's much too small and leaky, but a carbon tax nonetheless. Leave it to socialist economic systems to privatize the cost of carbon pollution.

September 8, 2011

Bloomberg shows us the Birdie

Why, if individual action won't do, would someone as business-savvy as Mayor Bloomberg invest in a mascot to get New Yorkers to change their behavior?

Why, if individual action won't do, would someone as business-savvy as Mayor Bloomberg invest in a mascot to get New Yorkers to change their behavior?

Well, it's cute. It even has its own Facebook persona.

Moreover, it does get individuals to change. If your goal is to get New Yorkers to stop idling their engines and to drink more tap water, tell them. Some may well do it.

The emphasis is on "some." At latest count, Birdie has 1,059 Facebook friends. That's more than your typical bird, but there's some growth potential in a city of 8,000,000.

To reach the masses, it can't hurt that many of the messages tell New Yorkers that making a change will save them money.

If doing the right thing is good for the planet and for you, tweet it from the rooftops.

If doing the right thing is good for the planet but actually costs you, good luck getting more than a few hipsters to listen. Save your advertising dollars. Instead, pass laws that make it in people's self-interest to do the right thing. New York has anti-idling and pro-recycling laws for good reason.

Sadly, of course, while it's terrific for NYC to have ambitious goals of slashing carbon emissions, even the Big Apple won't take much of a bite out of global pollution trends.

September 7, 2011

Is "environmental economics" an oxymoron after all?

Despite all the talk about environmentalists and economists needing to join forces, there's one underlying, deeply inconvenient truth: Environmentalists and economists often see the world from two entirely different points of view.

Ecologists—and, by extension, many environmentalists—look at the world, and they see overlapping waves of growth and decline: Hare populations grow and grow until wolves come along and decimate the hare population. Soon enough, wolves themselves collapse, leading to hares growing once again. Populations oscillate around a stable equilibrium.

Economists look at the world, and they see growth: Every successful economic model for the last hundred-odd years shows things pointing up, forever. "Steady state" for economists implies a steady rate of growth.

Ecologists, let's call them "pessimists," point to humanity overstretching its ecological footprint. We'd need several planets to support our current lifestyle forever.

Technological optimists point to the disembodiment of value, producing more and more value with less and less stuff.

"Ecological economists" have worked hard to merge the two points of view. They have solid critiques of standard economics, but sadly, no clear solutions. Their models often point to the need for disembodying value in order to shrink our ecological footprint. That's all good, but how do you actually get there, and how do you measure whether enough is enough?

Environmental economists focus on a much narrower question: how to ensure that everyone pays the full cost of their actions? We can't all worry about humanity's footprint on the planet whenever we go to the store. We can—and should—worry about whether we are paying the full price for whatever it is we are buying.

September 6, 2011

One person's cost, another's investment in the future

President Obama last week abandoned stricter air quality standards, caving to industry objections over cost. Tighter standards would not have been free, but abandoning them clearly isn't either, for two reasons:

#1: The lack of tighter standards will cause some 12,000 premature deaths and hundreds of thousands of lost work and school days. That comes with real costs to the economy. It's clear by now that the Clean Air Act of 1970 has improved worker productivity and growth. By 2010, GDP was as much as 1.5% higher because of the Clean Air Act. Cleaner air doesn't just smell better, it also helps the economy.

#2: There's an even more direct connection. Most economic models assume a Panglossian world of no unemployment and the economy humming along at full speed. That's clearly not the world we live in right now. A time with record unemployment is precisely when you want to boost the economy with additional investments: digging those proverbial holes and filling them, just to get things going again. Putting new scrubbers on power plants seems to be a much better idea than digging and re-digging holes, especially since it may well lead to additional benefits down the road. See point #1.

September 5, 2011

No pain, no gain

Plenty of studies show how we can save the planet and save money all at once. Many of them happen to be produced by McKinsey. Economists tend to deride them. If you could really save money by being green, why wouldn't everyone be green all the time?

Turns out there are plenty of obstacles.

McKinsey should know. If all markets were efficient all the time, there'd be no need for management consultants in the first place. Why would you hire someone to show you how you can do better, if you are perfectly efficient already?

But there's another reason why saying that climate policy will be free may not work.

This one is psychology: Why would something be worth doing, if it were free? Sensible climate action isn't nearly as expensive as some critics would like to believe, but talk of it being free may not help the cause. Cheap? Yes, but nothing worth doing is free.

(At the very least, you'll need to hire McKinsey to show you what to do. And that can get pricey.)

September 4, 2011

For richer and for greener

There are climate deniers—those who deny the basic chemistry and physics.

Then there are the "reasonable" ones—those who start by saying, "I believe global warming is real, but… ." More often than not, that "but" is the claim that doing something now would be too expensive.

Among those who espouse that claim, the most polished argument against doing something now is that we'll all be richer in the future. With more money, we'll be much better equipped to deal with the consequences of global warming. True enough. You first need to make a certain amount of cash to be able to hide in air-conditioned lairs.

But all of that misses a fundamental point: The richer we are, the more value we tend to place on unspoiled nature.

It's precisely because future generations will have more money to spend that they'd want to spend more on making the world a greener place. It also makes them more likely to want us to spend more on preventing the worst consequences of global warming—while that's still possible to do.

September 3, 2011

Could electric cars be more like cell phones?

We know there will be no lines for clean electrons. Electricity is a commodity that doesn't command a price premium, just because it's produced differently. But if you ship it differently, say in the form of a battery, it will sell for more.

There are indeed lines for iPhones, and even ordinary cell phones command a premium: We give up land lines to pay three times as much for (spotty) cell phone service, because the mobility is that much more convenient.

For some, the shift from century-old internal combustion engines to electric vehicles may be just that kind of change. EVs could offer an entirely different value proposition that goes much beyond appealing to the eco-conscious. Smooth battery swaps should beat smelly gas stations any day.

Perhaps making EVs as cheap as standard clunkers isn't the ultimate goal. Just make them appealing enough.

September 2, 2011

Self interest, German edition

Money—aka self interest—makes the world go 'round. If you alone decide to leave the rat race, it'll surely impact you, but it won't make much difference to the planet at large.

But what if an entire country decides that self restraint is the way to go?

German bankers make perhaps $100,000 where their American counterparts make $100,000s or millions. German civil servants routinely turn down lucrative private sector jobs because, well, it would be the wrong thing to do. The head of the German equivalent of Bank of America laments million-dollar banking bonuses and resents the 32-year-olds who get them across the Atlantic. All of that makes Germans the most solvent European and the ones now on the hook for bailing out everyone else.

Yet none of that stopped German banks from losing billions themselves. "Stupid Germans in Düsseldorf" were the last ones buying the worst financial products peddled by their greedy Wall Street counterparts. Blame it on blind faith in the goodness of others, or German tendency to stick to rules über alles and not to question those rules that tell them to buy anything AAA-rated, no matter how unbelievable the rating.

So yes, culture clearly drives behavior and can help entire societies move beyond narrow self-interest. I challenge you to find a German who doesn't recycle. But even an entire country moving beyond self interest can't prevent the globe from going down the tubes when others take them for suckers.

September 1, 2011

Nuclear numbers

Nuclear energy accounts for 20 percent of U.S. electricity generation.

Nuclear energy accounts for some 70 percent of carbon-free electricity.

Over half of U.S. nuclear plants are scheduled to retire between 2030 and 2040.

We may be producing a higher percentage of carbon-free electricity in 2030 than in 2040.

August 31, 2011

Moving beyond the drilling state of mind

Some think offshore oil rigs are beautiful marvels of modern technology. Others consider them obscenities, who, in turn, often marvel at wind turbines and rows of solar panels.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but it's clear we can't have our beautifully designed iPhones without any of the above.

It's also clear that wind and solar energy are attractive precisely because they can be a lot closer to where people actually live than the oil rig or coal plant that's (hopefully) far from where anyone could breathe in the exhausts.

I'm sure there'll be a time when wind turbines and solar panels will be signs of yesteryear. For now, they are one of the better shots we've got to avoid drowning in pollution and rising seas. This is not the time or place for nimbyism in any of its forms.

Gernot Wagner's Blog

- Gernot Wagner's profile

- 22 followers