Garry Kasparov's Blog, page 49

June 19, 2017

Worry about people, not jobs: Garry Kasparov | June 18th, 2017

BY SUMAN LAYAK, ET BUREAU | JUN 18, 2017

ORIGINAL ARTICLE AT THE ECONOMIC TIMES

In an email interview with ET, New York-based Kasparov shares his views on chess, AI, Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin.

Over the last 12 years, Russian chess Grandmaster Garry Kasparov has been a writer, human rights and democracy activist and a sometime chess-coach-cum adviser to top players. For an earlier generation, Kasparov is a superstar, probably the greatest ever chess player, a World Champion at the age of 22 in 1985 and a flag-bearer for human intelligence in matches against the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue (Kasparov won the first match in 1996 but lost the re-match in 1997). Twenty years later, Kasparov has written a book on the match, Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins. In an email interview with Suman Layak, New York-based Kasparov shares his views on chess, AI, Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. Edited excerpts:

Over the last 12 years, Russian chess Grandmaster Garry Kasparov has been a writer, human rights and democracy activist and a sometime chess-coach-cum adviser to top players. For an earlier generation, Kasparov is a superstar, probably the greatest ever chess player, a World Champion at the age of 22 in 1985 and a flag-bearer for human intelligence in matches against the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue (Kasparov won the first match in 1996 but lost the re-match in 1997). Twenty years later, Kasparov has written a book on the match, Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins. In an email interview with Suman Layak, New York-based Kasparov shares his views on chess, AI, Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. Edited excerpts:

On why the book has come 20 years after the match.

The approach of the 20th anniversary of the 1997 rematch was the catalyst, but I wouldn’t have written Deep Thinking if I hadn’t felt ready. It was still painful to look back at that catastrophe, but enough time had passed to be objective, to find the truth, even if it was unpleasant. The other factor was that I had a lot more to say about intelligent machines and human-machine relationship. I felt that this could be an important message for others as well.

On whether he would do it again

No, the strength of today’s chess machines makes me quite happy I’m retired! A free app on your smartphone is stronger than Deep Blue ever was. And a top engine on a decent laptop is likely unbeatable by even the best human on a good day. Engines don’t play perfectly, but they don’t make enough mistakes of the magnitude required for a human to beat them. Draw, yes, but probably not win. It was my blessing and curse to be the World Champion during the period in which chess computers went from laughably weak to practically unbeatable. It was a fascinating moment in my life, but in the historical perspective it’s a tiny blip.

On whether computers can take up human jobs, replace chess coaches

Job loss to intelligent automation is a critical topic, but one of the reasons I wrote Deep Thinking was because we are looking at it the wrong way, with dangerous repercussions. Worry about people, not jobs, not professions. The evolution of human civilisation is the replacement of human labour by technology. That’s progress. It’s essential, and makes our lives better, longer, more comfortable and productive. We should be concerned about what people will do if their tasks are taken over by machines, yes, but that problem will only get worse if we slow down instead of speed up automation and the development of new technology. Industries that automate also expand, leading to the creation of better jobs, even new industries. We need to focus on how to train people who are being displaced, how to keep them active. The good news is that smarter tools are also easier to use with less training. Computers are already teaching kids to play chess! But there will always be a place for human coaches and teachers, to help kids reach their potential — and not only in chess. With an infinite amount of information at everyone’s fingertips, it’s ridiculous to preserve the old teacher-student relationship. Teachers today should focus on teaching kids how to learn, not what to learn. Training methods and critical thinking are still essential.

On opponents Anatoly Karpov, Viswanathan Anand, Vladimir Kramnik

Enjoyed isn’t really the way to put it! In a professional game, especially in a World Championship match, it’s a life or death struggle, and even the thrill of victory leaves you exhausted. But I always felt a special surge of energy when facing Karpov who was, of course, my great rival over five World Championship matches.

Even in less consequential games later in our careers, I had a feeling like against no other opponent. We knew each other so well, and public interest was always high when we met. To answer more selfishly, my record against Anand was far better than against Karpov or Kramnik, so I suppose those games were more enjoyable in that way. Vishy was a formidable opponent so he inspired me to play my best, and more often than not it went my way.

On challenging current players

They are very strong, with Magnus Carlsen still a step above everyone else. But I haven’t been gone so long! I played many games against several of the players still near the top, especially Kramnik and Anand. Of the young generation, they are often very good technically and still need to show their fire and dedication. One reason I’m impressed with Wesley So is how hard he works. He has other chessboard talents as well, but his ability to focus and prepare is tremendous. I have no interest in big chess challenges. Top-level chess, especially classical chess, requires concentration and dedication. I have a million other things in my life today, from young children to books and politics. It’s not compatible with professional chess and I’m quite happy with my life.

On US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin

Putin long ago decided that the US was his enemy. It is the world’s most powerful nation and so it is a potential threat to his uncontested power as the dictator of Russia. And he can’t stay quiet since he needs international conflict to justify his power at home. More conflict was inevitable, but this scandal with Trump is a huge wildcard.

Why does he praise Putin, a brutal dictator who attacked the US election? Why does Russian propaganda attack the US constantly, but never say anything negative about Trump himself? So far, most of the known contacts are with Trump’s team, which has more Russian connections than Aeroflot. Trump may not be intelligent enough to be part of a grand conspiracy himself, but he may end up being prosecuted for trying to interfere in the investigation of his administration and allies, like Michael Flynn.

On the dichotomy of Edward Snowden finding sanctuary in Russia

It’s only a dichotomy if he wasn’t already working with Russian intelligence, either willingly or as a pawn. I have no special knowledge of Snowden’s activities, but his path afterwards, his welcome in Putin’s Russia and his willingness to allow himself to be used as a tool of Putin’s propaganda aren’t in his favour as a mere whistleblower or misguided zealot. You can be happy that what he exposed was exposed and still suspect he was an agent or traitor.

On democracy in Russia

There isn’t any democratic politics in Russia, only that approved by the Putin regime. The balance of power is between various camps of Putin’s allies, pushing and pulling for influence and cash, usually behind the scenes. You can’t speak of democracy or sully the word ‘election’ by talking about Russia. It’s a joke, a show to distract people, nothing more. Russia is a dictatorship and anyone who posed any sort of real challenge to Putin’s grip on power would be dead, in jail, or exiled.

June 6, 2017

“Deep Thinking” British tour | June, 2017

He did a string of brilliant media interviews (click on images for links) that included:

BBC Radio 4 Today

BBC Radio 2 Jeremy Vine – where he read an inspiring essay on what makes us human.

And beat Jeremy in under a minute at chess – Jeremy Vine called this interview ‘The highlight of my year’

He also made an appearance at Channel 4 News.

He then was the star performer in a string of wonderful, inspiring and sold out events, including

– A wonderfully memorable sold out event at Hay with Stephen Fry

– A talk with Demis Hassabis at Google – their biggest ever UK event! Which saw them use 3 overflow rooms with TVs to accommodate the 500 Googlers (half of Google’s staff) who were desperate to see Garry talk

– A superb book and ticket talk at the British Library

– A wonderful finale at the Emmanuel Centre that was packed to the rafters

We don’t need to lose out to machines, says the man who did | New Scientist | May 31st, 2017

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE AT THE NEW SCIENTIST

Two decades after his devastating loss to a supercomputer, chess legend Garry Kasparov is embracing his old adversary

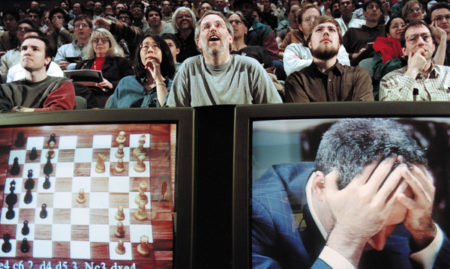

By Sean O’Neill

HE WAS fiery, flamboyant and merciless, and people loved him for it. It was 1985 when Garry Kasparov became the youngest ever world chess champion at just 22. He remained at the top for 20 years, but it was his epic battles with IBM’s supercomputer Deep Blue in 1996 and 1997 that catapulted him into the stratosphere. Billed as the ultimate Human vs Machine challenge, the first six-game match began badly for Kasparov, but he fought back to win 4-2. But in the second game of the rematch a year later, a flustered Kasparov needlessly resigned when he could have forced a draw. He never recovered psychologically and lost 2½ to 3½. It has taken Kasparov 20 years to get over his defeat – and to embrace his former adversary, artificial intelligence.

HE WAS fiery, flamboyant and merciless, and people loved him for it. It was 1985 when Garry Kasparov became the youngest ever world chess champion at just 22. He remained at the top for 20 years, but it was his epic battles with IBM’s supercomputer Deep Blue in 1996 and 1997 that catapulted him into the stratosphere. Billed as the ultimate Human vs Machine challenge, the first six-game match began badly for Kasparov, but he fought back to win 4-2. But in the second game of the rematch a year later, a flustered Kasparov needlessly resigned when he could have forced a draw. He never recovered psychologically and lost 2½ to 3½. It has taken Kasparov 20 years to get over his defeat – and to embrace his former adversary, artificial intelligence.

You’ve have just published a book in which you explore your defeat by Deep Blue. Was writing it a cathartic experience?

PRESS TO ORDER AT AMAZON NOW!

Yes, absolutely. There were many questions about my rematch with Deep Blue that I had avoided asking and the answers weren’t always pleasant. Even though it was 20 years ago, writing about it was a very painful experience. I’d never analysed those six games in depth using modern chess computers. I discovered that Deep Blue didn’t play very well either – at least not as well as we all believed at the time – and this made me feel even worse about how my terrible psychological state during the match led to my loss. Of course, it was only a matter of time before Deep Blue or another machine defeated me, but I played embarrassingly below my level.

If you could go back in time and take the draw in the second game of the rematch, would you?

Once a move is made it cannot be retracted, and if I had a time machine, I’m sure I could think of better uses for it. That match was such an anomaly, it has taken years for me to even attempt to draw lessons from it.

What are the broader lessons from your defeat?

As the proverbial man in man-versus-machine I feel obligated to defend humanity’s honour, but I’m also a realist. History has spoken: for nearly any discrete task, including playing chess, machines will inevitably outstrip even human-plus-machine. AI is hitting us in a huge wave, so it is time to embrace it and to stop trying to hold on to a dying status quo.

What did you make of the Go match between DeepMind’s AlphaGo and top player Lee Sedol?

I understand that AlphaGo played some genuinely unusual moves, strong moves that a top human would never consider. It doesn’t surprise me that there is room for this in a game as long and subtle as Go, where an individual move is worth less than in chess. It’s even possible that entirely new ways of playing Go will be discovered as the machine gets stronger. It’s also likely that humans won’t be able to imitate these new strategies, since they depend on the machine’s unique capabilities.

You called Deep Blue the end and AlphaGo the beginning. What did you mean?

Chess was considered a perfect test bed for cognition research but it turned out the world chess champion could be beaten while barely scratching the surface of artificial intelligence. I’m sure some things were learned about parallel processing and the other technologies Deep Blue used, but the real science was known by the time of the 1997 rematch. Not to downplay the Deep Blue team’s achievement, but AlphaGo is an entirely different thing. Deep Blue’s chess algorithms were good for playing chess very well. The machine-learning methods AlphaGo uses are applicable to practically anything.

What does that mean for the wider world?

AI is clearly booming as a technology, but there’s no way to know what part of the curve we are in. Periods of rapid change are turbulent and confusing, and we are seeing the social apprehension that comes with a wave of automation, even more so because robots and algorithms are moving in on jobs that require college degrees. Of course, real dangers and human anguish come with the AI wave, and we can’t be callous toward those caught in the turbulence. But it’s easy to focus on the negative things because we see their impact much more clearly, while the new jobs and industries of the future can’t be imagined so easily. I think we’ll be surprised, as we have been throughout history, by the bright future that all these amazing tools will help us build, and how many new positive trends appear.

Computer scientist Larry Tesler once said “intelligence is whatever machines haven’t done yet”. Where are the next targets?

Where aren’t they? The biggest public impact might be felt in medical diagnosis. This is an area that doesn’t require 100 per cent or even 99.99 per cent accuracy to be an improvement on human results. You wouldn’t trust a self-driving car if it was only 99 per cent accurate. But human doctors are only 60 or 70 per cent accurate in diagnosing many things, so machine or human-plus-machine hitting 90 or 99 per cent will be a huge improvement. As soon as this is standard and successful, people will say it’s just a fancy tool, not AI at all, as Tesler predicted.

“The world champion could be beaten while barely scratching AI’s surface”

What happens if AI, high-tech surveillance, military tech, and communications are sewn up by the ruling class?

Ruling class? Sounds like Soviet propaganda! New tech is always expensive and employed by the wealthy and powerful even as it provides benefits and trickles down into every part of society. But it seems fanciful – or dystopian – to think there will be a harmful monopoly. AI isn’t a nuclear weapon that can or should be under lock and key; it’s a million different things that will be an important part of both new and existing technology. Like the internet, created by the US military, AI won’t be kept in a box. It’s already out.

Will handing off ever more decisions to AI result in intellectual stagnation?

Technology doesn’t cause intellectual stagnation, but it enables new forms of it if we are complacent. Technology empowers intellectual enrichment and our ability to indulge and act on our curiosity. With a smartphone, for example, you have the sum total of human knowledge in your pocket and can reach practically any person on the planet. What will you do with that incredible power? Entertain yourself or change the world?

“Deep Thinking: Where machine intelligence ends and human creativity begins” by Garry Kasparov is published by Hodder & Stoughton

This article appeared in print under the headline “Endgame? It’s just the beginning”

June 3, 2017

Is AI the end of jobs or a new beginning? | Review of “Deep Thinking” |WashPost

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

by Vivek Wadhwa

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is advancing so rapidly that even its developers are being caught off guard. Google co-founder Sergey Brin said in Davos, Switzerland, in January that it “touches every single one of our main projects, ranging from search to photos to ads … everything we do … it definitely surprised me, even though I was sitting right there.”

The long-promised AI, the stuff we’ve seen in science fiction, is coming and we need to be prepared. Today, AI is powering voice assistants such as Google Home, Amazon Alexa and Apple Siri, allowing them to have increasingly natural conversations with us and manage our lights, order food and schedule meetings. Businesses are infusing AI into their products to analyze the vast amounts of data and improve decision-making. In a decade or two, we will have robotic assistants that remind us of Rosie from “The Jetsons” and R2-D2 of “Star Wars.”

PRESS TO ORDER ON AMAZON NOW!

This has profound implications for how we live and work, for better and worse. AI is going to become our guide and companion — and take millions of jobs away from people. We can deny this is happening, be angry or simply ignore it. But if we do, we will be the losers. As I discussed in my new book, “Driver in the Driverless Car,” technology is now advancing on an exponential curve and making science fiction a reality. We can’t stop it. All we can do is to understand it and use it to better ourselves — and humanity.

Rosie and R2-D2 may be on their way but AI is still very limited in its capability, and will be for a long time. The voice assistants are examples of what technologists call narrow AI: systems that are useful, can interact with humans and bear some of the hallmarks of intelligence — but would never be mistaken for a human. They can, however, do a better job on a very specific range of tasks than humans can. I couldn’t, for example, recall the winning and losing pitcher in every baseball game of the major leagues from the previous night.

Narrow-AI systems are much better than humans at accessing information stored in complex databases, but their capabilities exclude creative thought. If you asked Siri to find the perfect gift for your mother for Valentine’s Day, she might make a snarky comment but couldn’t venture an educated guess. If you asked her to write your term paper on the Napoleonic Wars, she couldn’t help. That is where the human element comes in and where the opportunities are for us to benefit from AI — and stay employed.

In his book “Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins,” chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov tells of his shock and anger at being defeated by IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer in 1997. He acknowledges that he is a sore loser but was clearly traumatized by having a machine outsmart him. He was aware of the evolution of the technology but never believed it would beat him at his own game. After coming to grips with his defeat, 20 years later, he says fail-safes are required … but so is courage.

Kasparov wrote: “When I sat across from Deep Blue twenty years ago I sensed something new, something unsettling. Perhaps you will experience a similar feeling the first time you ride in a driverless car, or the first time your new computer boss issues an order at work. We must face these fears in order to get the most out of our technology and to get the most out of ourselves. Intelligent machines will continue that process, taking over the more menial aspects of cognition and elevating our mental lives toward creativity, curiosity, beauty, and joy. These are what truly make us human, not any particular activity or skill like swinging a hammer — or even playing chess.”

In other words, we better get used to it and ride the wave.

Human superiority over animals is based on our ability to create and use tools. The mental capacity to make things that improved our chances of survival led to a natural selection of better toolmakers and tool users. Nearly everything a human does involves technology. For adding numbers, we used abacuses and mechanical calculators and now spreadsheets. To improve our memory, we wrote on stones, parchment and paper, and now have disk drives and cloud storage.

AI is the next step in improving our cognitive functions and decision-making.

Think about it: When was the last time you tried memorizing your calendar or Rolodex or used a printed map? Just as we instinctively do everything on our smartphones, we will rely on AI. We may have forfeited skills such as the ability to add up the price of our groceries but we are smarter and more productive. With the help of Google and Wikipedia, we can be experts on any topic, and these don’t make us any dumber than encyclopedias, phone books and librarians did.

A valid concern is that dependence on AI may cause us to forfeit human creativity. As Kasparov observes, the chess games on our smartphones are many times more powerful than the supercomputers that defeated him, yet this didn’t cause human chess players to become less capable — the opposite happened. There are now stronger chess players all over the world, and the game is played in a better way.

As Kasparov explains: “It used to be that young players might acquire the style of their early coaches. If you worked with a coach who preferred sharp openings and speculative attacking play himself, it would influence his pupils to play similarly. … What happens when the early influential coach is a computer? The machine doesn’t care about style or patterns or hundreds of years of established theory. It counts up the values of the chess pieces, analyzes a few billion moves, and counts them up again. It is entirely free of prejudice and doctrine. … The heavy use of computers for practice and analysis has contributed to the development of a generation of players who are almost as free of dogma as the machines with which they train.”

Perhaps this is the greatest benefit that AI will bring — humanity can be free of dogma and historical bias; it can do more intelligent decision-making. And instead of doing repetitive data analysis and number crunching, human workers can focus on enhancing their knowledge and being more creative.

May 30, 2017

Garry Kasparov at Ted Talks | May, 2017

We must face our fears if we want to get the most out of technology — and we must conquer those fears if we want to get the best out of humanity, says Garry Kasparov. One of the greatest chess players in history, Kasparov lost a memorable match to IBM supercomputer Deep Blue in 1997. Now he shares his vision for a future where intelligent machines help us turn our grandest dreams into reality.

Watch original video at Ted.com

May 24, 2017

Kasparov on interplay between machine learning and humans | Business Insider | May 24th, 2017

by Elena Holodny

May 24, 2017

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE AT BUSINESS INSIDER

Garry Kasparov, one of the greatest chess players of all time, is famous for his pair of faceoffs against the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue.

Kasparov won the first match against the computer, 4-2, in 1996, but lost in the rematch, 3½-2½, in 1997. He recently published a book, “Deep Thinking,” about the experience.

Business Insider recently spoke with Kasparov about Deep Blue, his thoughts on AI, and machine advancements over the past 20 years — and how he sees the interplay between machine intelligence and humanity.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Elena Holodny: What’s the biggest misconception about AI?

Garry Kasparov: AI as a concept is surrounded by mythology.

Most of the things we mention we understand. You know, if we say “white,” we all see it’s white. If we talk about elements of computer science or some general items, we are in agreement. There’s no need to go into definition.

Now with AI, the moment we mention “AI,” you should spend a considerable amount of time with the person understanding what is AI for this very person. And that was one of the purposes of my book, just to remove the mythology, to look at the problem objectively, without the utopian expectations or without dystopian fears.

And also to understand, what is the nature of human intelligence. Obviously I understand my own limitations. But it is important to recognize when we say AI, what do we mean, and what do we expect?

One of the biggest problems that arise in the beginning of the conversation is: Do you mean intelligence as a result of the AI or as a process? Because when you look back at my matches that I’ve played with chess computers, now, if we stick with the intelligence as a result, then by the definition of its output, Deep Blue was intelligent because it played grand-master-level chess. Now, if you look at the process, if you try to understand the intricate details of human intelligence, now Deep Blue, this phenomenal speed of 200 million positions per second, offers you no information because it was as intelligent as your alarm clock.

And it’s a big issue. Many people simply don’t recognize that this discussion — still open-ended discussion — can bring us to very different conclusions. And probably if we’re talking about misconception, the first misconception is that people simply don’t agree what they mean by saying “AI” and why AI could be good or bad for us in the future.

Holodny: You draw the distinction between the process of thinking versus the result. Obviously computers are good at calculating and humans are very good at analogical thinking and seeing patterns.

Kasparov: We have different ways of evaluating the positions.

For instance, if you try to oversimplify it, in the game of chess, there’s a certain position and I have to make my choice. My decision will be based on, very roughly, 1% of calculation — probably even less — and 99% or more of understanding, of looking at patterns, drawing information from my previous experience.

Now the machine will be exactly the opposite. It will be 99% calculation and some percent of understanding, though this understanding is growing.

Today, chess programs — they are far more sophisticated than Deep Blue. A free chess app on your mobile is better than Deep Blue, stronger than Deep Blue. So maybe it’s no longer 99-to-1, but still it’s the decision, the core of the machine’s decision, is always based on calculation.

And that’s why we have to realize that all experiments that are related to the games when you have humans versus machines in the games — whether it’s chess or “Go” or any other game — machines will prevail not because they can solve the game. Chess is mathematically unsolvable. The number of legal moves is about 1045 …. But at the end of the day, the machine doesn’t have to solve the game. The machine has to win the game. And to win the game, it just has to make fewer mistakes than humans. Which is not that difficult since humans are humans and vulnerable, and we don’t have the same steady hand as the computer.

So chess, as we found out, could be crunched once the hardware got fast enough, the database got big enough, and the algorithm got smart enough. But again, even if you move from Deep Blue and chess to AlphaGo, which is more complicated, more strategic, and, I would say, looks more like our expectations about AI, we’re still staying in the territory of games where the machine prevails because humans make mistakes.

It’s not that machines are impeccable. Looking, for instance, at the games we played in 1997, and using modern computers, I found out that it’s not just I who made mistakes, but Deep Blue made quite a few serious mistakes … serious mistakes that could bring the game from a drawing position to a losing one. And I’m sure in 20 years, we’ll have even more powerful machines, and will look and say, oh by the way, maybe it’s not that easy.

We should simply accept the fact that the way machines make decisions is different, and rather look at the result. If machines are providing results that we are looking for, you would mind how much human understanding was used in the process. And more likely we should look for the way of combining human skills and machine skills. And that, I believe, is the future role of humanity, is just to make sure it will be using this immense power of brute force of calculation for our benefit.

Holodny: A chess piece’s relative value can change over the course of the game, or a weaker piece could be in a stronger position than a stronger piece. How does a computer think about shifts like that?

Kasparov: The machine doesn’t care about psychological problems like sacrificing a stronger piece. It looks at immediate returns. So the smart algorithms and very fast hardware, they allow a machine to look quite deep, to actually see the consequences.

What you mentioned is still one of the weakest elements, because long-term compensations — sacrificing some material for long-term strategic advantages — that could be challenging for a machine because it still has to see immediate returns. But in most cases, these kinds of sacrifices, they are within the machine’s reach. And as long as it can see that at move four or five it will get something in exchange, it’s not a big deal.

For example, from the machine’s perspective, the solution is very, very simple: You just have to sacrifice the queen. For the machine, it doesn’t matter because it immediately sees that in two moves, it will win and this is the only way to win the game.

But still, for a human player, just to give up a queen for nothing, even for one move — you simply don’t look at that. Humans have some kinds of dead zones. I don’t look there because it’s against what I learned: You don’t give up the queen.

Machines look at everything, so that’s another big advantage. And as I said, the areas where machines are relatively vulnerable, they are quite narrow. But still, if you bring human-plus-machine versus the most powerful machine, the former combination will win because human advice in this very special situation could be vital.

Holodny: It’s interesting because that’s true of other industries too. In neuroradiology, a human is less accurate than a machine, but a human and a machine are more accurate than a machine.

Kasparov: Yes, that exactly. A machine helps us to annihilate our weaknesses. We don’t have a steady hand. We can lose all vigilance. We can be distracted by something that is not that relevant. But we have intuition. We can feel certain things. And with a machine you can check whether it’s right or wrong. That’s why by bringing [the two] together, you create a very, very powerful combination.

Now, what is the most important element of this combination? It’s an interface. Let me stick with chess, but I’m sure you can look for other examples. [Sometimes] you have a relatively weak player, not a top player, because she or he could be a better operator. Because with the machine it’s very important to help the machine, rather than trying to play on your own. So you don’t need too many of your ideas. Yeah, you have to look, but still, if you have a powerful interface, especially if you deal with more than one computer; if you start bringing them together and checking different lines, [then] the operator has an advantage — a good operator — over a very strong player. Because at the end of the day, all that’s needed is human skills to maximize the machine’s output, rather than great human understanding to be assisted by the machine.

Holodny: It’s easy to see how human’s intuition can be weaker than a computer, but do you think there are examples when it’s an advantage to act on intuition?

Kasparov: Again, we are on a very slippery ground of semantics. You know, what is intuition? Some of it’s based on experience.

Holodny: Yeah, “Napoleon’s glance,” for example.

Kasparov: Yeah, but taking just, you know, pure human decision versus machine, I think that if you look for … If you run a test, and if you have enough samples, I think the machine will prevail eventually. But there are certain moments where, intuitively, I would bet on intuition — especially if we are in the area where machine expertise is limited.

Holodny: Like an early chess program?

Kasparov: Let’s talk about 2017. Forget about early chess programs. I reached a conclusion that anything that we know how we do, machines will do better. Now, the key element of this phrase is, “We know how we do it.” Because we do many things without knowing exactly how we do them. So this is the area where machines are vulnerable, because it still has to learn from some kind of experience. It needs something — at least the rules of the game. You have to bring in something that will help the machine to start learning. It’s like square one. If there’s nothing there, if you can’t explain it, that’s a problem.

One of my optimistic prophecies is based on the assumption that machines could have the best algorithms in the universe, but it will never have purpose. And the problem for us to explain purpose to a machine is because we don’t know what our purpose is. We have the purpose, but we still … When we look at this global picture, a universal picture, to understand what is our purpose being here on this planet? We don’t know. So that means we’re still searching, and will not be able to pass this message to the machine. And it’s a problem for us, some kind of comfort, though. People say it’s more like preaching … OK, maybe preaching, yes.

Because, as I mentioned in the book and all my lectures, is that people’s minds are polluted by these dark pictures of the future from Hollywood: “The Terminator,” the Skynet, “The Matrix.” It’s world where there’s no room for humans, or they have to fight against the machines. I think it’s just a way, way, way, way in the future. Is it going to happen? I don’t know. For me, these debates are not similar, but they resemble debates about how the sun will turn into a supernova in 4 to 5 billion years. Frankly, I don’t care. [Laughs]

Holodny: How does it feel playing against AI where you don’t perceive any emotional changes during the game — meaning the psychological element of the game doesn’t exist — versus a person? For example, you versus Deep Blue.

Kasparov: That was quite an experience, and I’ve been playing machines for many years. In the book, I started describing the story in Hamburg, in 1985 … and I’m still trying to figure it out whether it’s my curse or my blessing that when I became world champion, machines were weak — just a laughing stock — and when I left chess in 2005, machines were unbeatable. So I didn’t just witness that [but] I was an active part of this process. And, in fact, after matches with Deep Blue, I played two more matches with other programs, with a German program and an Israeli program in 2003, and both matches ended in a draw.

To sum up objectively, I think I was still stronger maybe the next year. If IBM didn’t retire the machine and we played, I think I had a chance of winning. But from the historical perspective, it was immaterial. I can go even further saying that since the machine managed to win the first game in the Philadelphia match [1996] — the match that I won eventually — in my view that’s the bigger milestone than even 1997, because if the machine was able to win one game, the rest is a matter of time. One year, two years, five years … but we were there. We were on that road. So that eventually the machine will be able to win the match. So it was clear that the machine had reached the level where beating the strongest players would be just a matter of a couple more decimal places in speed and a few more smart ideas for algorithms.

But going back to this match, I’m leaning toward blessing, because it doesn’t happen often that you’re part of history. So even if it’s not one of the most comfortable parts, it’s still history. And I think, you know, what’s happened there is we helped chess players — and the game of chess — to understand and to test many new ideas.

It’s interesting that the greatest minds of computer science, the founding fathers, like Alan Turing and Claude Shannon and Norbert Wiener, they all looked at chess as the ultimate test. So they thought, “Oh, if a machine can play chess, and beat strong players, set aside a world champion, that would be the sign of a dawn of the AI era.” With all due respect, they were wrong. It’s an important step forward, but we’re still, still far away, and that’s why I think it’s the best lesson from this match and from the game of chess is that we could see much clearer how humans and machines can cooperate because that’s the way to move forward. And I’m always saying that it’s for us to find new challenges.

So, somehow, AI is playing an important role of breaking up the ice of complacency. We have a comfortable life, we just don’t want to take risks. AI is threatening too many comfortable jobs to make people think about taking risks again.

Holodny: You argue that machines and humans working together is a stronger combination, but you also argue at the end of your book more generally that machines can make humans more human. Can you explain your thinking here?

Kasparov: It’s an interesting debate. I was part of this debate at the University of Toronto about six months ago. So, there was this Oxford-style debate. The house motion was: “Will machines make us more human or not?” I defended the house motion — just, it’s what it was. And I have to say it was very close. It started, I think, at something like 51-49, in favor, and we lost, 49-51.

But it’s amazing, the paradox of this debate: A very good debater on the other side played Trump on us. Because, you don’t do it in debates; you don’t start discussing the definition of the house motion [and] that’s what he did, which is just a violation of the rules. And you don’t attack opponents, but that’s another story. But it’s amazing that we lost the debate because he used very human arguments.

It’s quite funny, but it’s also interesting because I was learning from this process, and my argument was that, look, if we keep an optimistic view about the future, we definitely have to look for our place. Not to be redundant. And that means we have to emphasize what makes us unique.

As I said, everything we know how to do, machines will do better. So what about other things?

Machines taking over jobs — it’s the history of civilization. Replacing farm animals, old forms of manual labor, now taking over small, menial aspects of cognition. But there’s still plenty of room for creativity, for curiosity — many things that are related to passion, like art. But also, things about human communication and challenges, massive challenges that we left behind because we didn’t want to take so much risk, such as space exploration, deep ocean exploration.

For us to make sure that we have full lives, meaningful lives, we will have to elevate our unique human qualities. And I think we know now, we can see clearly what makes us different from machines. And that’s why the future is enhanced humanity.

The opposite argument is that we will end up being cyborgs. It’s an interesting argument and it’s amazing: Every debate moves from technology to philosophy. Now, we’ll use some kind of devices that we’ll implant — we’ll see better, we’ll run faster, we’ll lift more weight. But it doesn’t change humanity — it’s like taking a drug. So this is doping. This is a form of electronic doping, but it doesn’t change you. Even if you have a few implants that are making you faster, you are still the same human.

Now, the idea that you can remove intelligence from a human body and put it somewhere else — that’s an interesting question. But this is something that is far from being understood. Because then the natural question is, can we imagine our intelligence, our brains functioning outside of our bodies? Is it all connected? How does it work? Because it’s not just simply brain, but it’s also the way we move, and — that’s what makes us different — also the passion and the character.

So there are many things that you cannot break down in numbers. And as long as we don’t know how to describe the way our intelligence functions, the fear that human bodies will become irrelevant in the process — this fear is a gross exaggeration.

So that’s why for me, I believe more than ever, machines will put new challenges, and that means we’ll have to be more creative and more human, because that’s the way to make the difference.

Holodny: OK, just some fun questions for the end. What do you think is the biggest misconception about chess?

Kasparov: I’m afraid the misconception is very much based on the image projected by some of the great books, like Nabokov’s “The Luzhin Defence” or Stefan Zweig’s “Chess Story” — it’s about chess players being kind of nerds. Just playing in the dark corner of a café and just being geniuses, but totally removed from the real world. Yes, we have cases in our game — Paul Morphy, Bobby Fischer. But when you look at the numbers of chess players who were detached from reality and compare to the general, chess is a totally sane game.

This misconception has been gradually removed because more and more kids are playing chess. But still it’s very much alive. The game — it’s a nonmainstream game. And the irony is that when you look at Hollywood, it kept using chess as the symbol of intelligence for its heroes, for its top characters, all the time. So it’s from “Casablanca” to “Harry Potter.” You always have chess as a very important element to demonstrate intelligence, while in normal life people think it’s just a weird intelligence — like AI. [Laughs]

Holodny: What advice would you give to young chess players who want to play seriously?

Kasparov: Look, I would say, you have a unique chance of learning more about the game of chess with your computer than Bobby Fischer, or even myself, could manage throughout our entire lives. What is very important is that you will use this power productively and you will not be hijacked by the computer screen. Always keep your personality intact.

Remember that the machine is there to help you, because at the end of the day, you’re not playing freestyle chess, advanced chess, human-plus-machine. If you are playing against other humans, it’s about winning the game. The machine will not be assisting you, unless you are cheating of course. [Laughs] And since the machine is not there, you have to make sure that everything you learn from the computer will not badly affect the way you play the real game.

Holodny: What separates a good chess player from a great one? Or a grand master from a world champion?

Kasparov: Oh it’s a tiny difference.

Holodny: Is it something you perceive as a player?

Kasparov: Somehow it’s your ability to operate different kinds of positions. If you want, again, to oversimplify: A very strong player can manage and can just know how to manage a thousand positions. I get it; it’s a very arbitrary number. So then you have the world champion who could do more. But, again, any increase in numbers creates, sort of, a new level of playing.

And then you go to the very top, and the difference is so minimal, but it does exist. So even a few players who never became world champion, like Vassily Ivanchuk, for instance, I think they belong to the same category.

I would say that when you go to the very, very top, it’s an ability to come up with new ideas, with something new, to make the difference. Every world champion, every player who was traversing this universe, managed to bring something new to the game. This ability to always find some unconventional ways. That makes the final difference.

Holodny: Is chess beautiful to you?

Kasparov: Oh absolutely. It’s endlessly beautiful. I haven’t stopped enjoying great games, and when I see a nice endgame, for instance, especially when there are very few pieces left. Oh, I can’t help think, “Wow, how beautiful it is.”

And now, because of computers, we have a new technique of composing studies, endgame studies. They look at the positions from the large databases, and all pieces’ positions are already calculated by the machine. More than 100 terabytes of information. And then they create studies that lead to these positions. Sometimes it’s really beautiful.

So there are so many great things that you can discover. As I said, the number of legal moves is infinite, but if you find this, the little jewels in the tons of garbage.

Holodny: It’s interesting that this is maybe the one thing machines actually can’t do.

Kasparov: But again, you need humans to actually look for the jewels.

Holodny: Exactly.

Kasparov: To understand how beautiful it is. The geometry — it’s just amazing. You know, if I’m in a bad mood, I always look at the chessboard, just to find something that can cheer me up.

Holodny: So I guess it gives you purpose?

Kasparov: [Laughs] Yes.

May 23, 2017

A Conversation with Garry Kasparov | Thought Economics with Vikas Shah | May 21, 2017

A Conversation with Garry Kasparov

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE AT THOUGHT ECONOMICS

ARTICLE & INTERVIEWS BY: VIKAS SHAH / @MRVIKAS

It is that small number of truly powerful minds in our society who can reflect our past, present and future with a degree of lucidity and truth that makes us stand up and listen. These polymaths bring expertise from many fields of life together, creating the serendipitous and insightful provocations that enable us to see who we are.

Garry Kasparov is one of those minds. Born in Baku, Azerbaijan, in the Soviet Union in 1963, he came to international fame at the age of 22 as the youngest world chess champion in history in 1985. Garry defended his title five times and his famous matches against the IBM super-computer Deep Blue in 1996-97 were key to bringing artificial intelligence, and chess, into the mainstream.

Kasparov’s was one of the first prominent Soviets to call for democratic and market reforms and was an early supporter of Boris Yeltsin’s push to break up the Soviet Union. In 1990, he and his family escaped ethnic violence in his native Baku as the USSR collapsed. In 2005, Kasparov, in his 20th year as the world’s top-rated player, retired from professional chess to join the vanguard of the Russian pro-democracy movement. In 2012, Kasparov was named chairman of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation, succeeding Vaclav Havel. Facing imminent arrest during Putin’s crackdown, Kasparov moved from Moscow to New York City in 2013.

Press to order on Amazon Now!

In this exclusive interview, I spoke to Garry about democracy, dictators, the instability in our world, his hopes for the future and how artificial intelligence will allow us to embrace our humanity.

Q: Why does democracy matter?

[Garry Kasparov] If we look at human history, we can see a simple answer to the question of democracy. This system [democracy] provides the best conditions for individuals and society to flourish.

Most of the world’s wealth has been produced by democratic countries, and whilst people may point to China and other countries where living standards are growing… the driving engine of innovation, which is the foundation of human progress, still sits in the heart of the free world.

Free people are far more capable of realizing their potential.

Q: Why do we have such instability in our world?

[Garry Kasparov] History is not linear, like the chapters of a book… History moves through seasons, and so winters are inevitable.

After the end of the Cold War, when a big chapter of human history was closed with liberal democracies winning convincingly against communism, no game-plan was offered in exchange for the institutional infrastructure that served us during the cold war. The United States and Europe, instead of coming up with new ideas and frameworks, decided to stay with the old, incumbent, political frameworks without offering any changes (for example) to the United Nations and other world institutions. It was about getting rich, enjoying life, and celebrating the end of history- but guess what, history doesn’t end.

We were all thrilled by the end of the cold-war, but without a map for the future we will lunge from crisis to crisis.

If you offer no vision for the future, someone else will. Our geopolitics cannot tolerate a vacuum, and if you retreat- whether physically or ideologically- someone else will come up with a plan which may not be complementary for democracy.

Democracy produced high living standards, technology and wealth and many people benefited. In many countries, authoritarian leaders could exercise power by suppressing democracy at home, but exploiting the instruments of democracy abroad. Putin uses high oil prices, the western financial system, and the technology of the free world. This created much better living standards for the Russian people, but slowly eroded at their freedom. Then, when oil prices fell, Russians were left without the economic and other freedoms required for growth. A similar result, even more extreme, is happening in Venezuela. Repressive systems have no resiliency.

The free world has been living in a complacent status-quo, avoiding risk and creating political and economic stalemate, reducing growth. This environment lacks dynamism and thus encourages the fringes to be more vocal; representing those groups who are most frustrated by the situation.

We live longer than ever before, demand better conditions than ever before, and older people vote in much greater numbers than the young. Guess what, older people want the status-quo, and politicians respond to that- creating more stagnation. In Europe and the United States this created a simultaneous rise in fringe parties on the left and the right. In the United States you had Donald Trump, but also Bernie Sanders. In the United Kingdom, you have Jeremy Corbyn and Nigel Farage. In France you have Le Pen and Mélenchon.

We are seeing political upheaval in all major western countries which tells us that there is something fundamentally wrong with public mood.

Q: Why does society keep repeating such old behaviors?

[Garry Kasparov] The progress our world has made has primarily occurred in what has been termed the ‘free world,’ the remaining 87% of the population- who live in the ‘un-free world’ have not seen much of the benefits.

For political leaders such as Putin, Erdogan and their peers; conflict remains a very important part of their legacy. They have to try to legitimise their rule without fair elections, and foreign confrontations give them a vehicle to justify their claim on power.

Potential for conflict always exists in our world, like a volcano. We may normally see only a few bubbles, but every now and again the explosive forces rise to the surface.

Look at how Trump raised the Mexican issue, he always looked for confrontation in his political campaign. In the big picture, this is no different to the arguments laid down by Putin, Erdogan or the leader of North Korea… I’m not going to put Trump on the same level as them, of course, but as a character you see the same mechanism in action. It works.

People like Trump rally people behind them by pointing out threats; these may be real, but most likely are imaginary or inflated. Then he says, “only I can protect you.”

In the free-world, people are getting lazy and complacent after decades of continuous improvement of living standards. The economy however, does not always go up, and we should expect dives. We are trying to prevent a dive now by printing money, slowing the economy down, and piling up debt. This creates an uncomfortable situation for many people who were used to living conditions going up decade to decade. This is the complex of the Baby Boomers, the first generation that never experienced the threat of extermination, never experienced a major war, and only had good news. For this generation, they had technological progress but growth has stalled. They can easily therefore follow someone who blames migrants, minorities and others. It is always easy to blame someone for your unwillingness or inability to act.

Q: What would be your advice to the next generation?

[Garry Kasparov] More and more young people are getting interested in politics, and we should praise Trump for waking them up, even though that was not his intention.

Democracy is not something that is granted forever. Ronald Reagan once said, “Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction” and our democratic instruments have got rusty, as people assumed they would always work automatically.

The Trump victory demonstrated that many traditional pillars of democracy, such as avoiding conflict of interest and separation of powers—judicial from executive and legislative—are in danger. The only solution to stopping this decline is to engage in politics, not give up.

Look at the chaos being spread around by Trump’s total incompetence, just in the first few months of his Presidency. It is perhaps this chaos that has woken voters up to fight back against the rise of populism.

Trump isn’t intelligent enough to drive populism, but his inner circle… people like Steve Bannon… point out existing problems. Whether you talk about Farage, Le Pen or Bannon, they point out existing problems, saying the current government cannot run the country. Their solutions however will only ever make the situation much worse.

It’s very important to have an educated debate around democracy. People have immense power in their pockets. When I talk to young people, I emphasise they have enormous power in their smartphones- which are several times more powerful than the fastest supercomputers of the previous generation.

The younger generation can use this power to get engaged in politics. They can fight back against political issues like rising debt and the environmental crisis. If younger people don’t vote, older people will win, and guess what – older people don’t care what will happen in 30 years, of course they will vote for more debt!

There is always a balance of interest, and if you want to improve your life- think about what you want the world to look like in 20-30 years, and get engaged in political change now while you still have the chance.

Q: What could we achieve by cooperating with technology rather than fighting it?

[Garry Kasparov] We cannot think about technology in confrontational terms. There is no race against the machines, there is no fight, no war. We have to end this long, historical confrontational narrative.

Playing chess, I learned the dramatic effect combining humans and machines. Humans have intuition, can recognise patterns and positions, and machines have brute-force of calculation and memory. By bringing these capabilities together in other walks of life, we can achieve incredible results.

Whilst machines are taking over more parts of our lives, and people say this is killing many jobs, we have to realise this has been happening for thousands of years. Machines replaced farm animals, then manual labour, and now they’re taking over jobs from people with college degrees and twitter accounts- and everyone is making a big noise. Replacing manual labour allowed humanity to concentrate on developing our minds, and now, perhaps by taking over more menial aspects of our cognition, machines will help us to look for greater creativity, curiosity and happiness.

There are many aspects of humanity which make us indispensable, and we have to find the right interface between us and technology. I don’t want us to be so bothered about the long term future. The Terminator and the Matrix were great movies, but created a dystopian and fearful vision of the future; they think machines will take-over. Machines will of course take jobs, but they will create new jobs too.

New technology takes old jobs, creates new jobs, and generates to economic growth; this is how we will move forward. Instead of talking of jobs lost, we have to focus on the people who need help with this, and may find difficulty adjusting. If we slow down the cycle, we are just creating more pain- old jobs will disappear, entire careers and sectors will be automated, but new jobs will not be created fast enough to generate the growth we need unless we keep going forward.

Many of the problems that people are concerned about are too far in the future. Instead of worrying about powerful artificial intelligences in the future, we should be concerned about the lack of intelligence in the Oval Office today!

Embracing technology will allow us to continue those great endeavours of humanity such as exploring space and the oceans; things which are too risky for us to do otherwise. Machines are pushing people to new frontiers, and teach us that complacency and the status-quo are not working.

Q: What was it like for you to play chess against a machine?

[Garry Kasparov] Deep Blue was anything but intelligent. Once databases were big enough, hardware was fast enough, and algorithms were smart enough, chess could be number-crunched. Today, a free chess app on your phone plays better than Deep Blue, but that’s the way technology always goes. Deep Blue was a great achievement, and reached its goal, so demanding that it also be conscious, or sentient, or be able to explain how it beat me, is ridiculous. Computers of that age were not intelligent in the sense most people use the term, but this does raise the philosophical question of whether the result of the process is the sign of intelligence, or the process itself.

Many people believe AI will replicate the way we make decisions, but today we have machines such as IBM Watson and Alpha Go which are much more likely to satisfy our expectations of this- but in so many areas, machines can’t match us.

Algorithms are improving all the time, but they do not have a purpose. We need humans for that.

What I learned from the match with Deep Blue was that anything we know how to do, we can invent machines to do better, irrespective of whether that is manual or intellectual. There are however, so many things we do that we don’t know how we do- and that’s where we need to concentrate our efforts.

For these things, the unknowns, the mysteries, the challenges, if we don’t know what our purpose is, we cannot, therefore, tell machines to have that same purpose. They will help us achieve our new goals if we keep improving them.

There are so many things in life we do because we know they’re right, without really knowing why. Those intuitive things exist in a different domain.

We have to remain creative and push for new frontiers. Perhaps one day machines will be able to create algorithms from scratch, and teach each other what they need to know, but this won’t happen fast. We are seeing a version of this now, on a limited scale, with AI tools improving themselves incrementally, and this is the cycle we need to expand.

We need to stop making predictions because technology will always prove us wrong… Look at today’s lucrative jobs such as drone pilot, 3D printing engineer or social media manager- these jobs simply didn’t exist even ten years ago….

A hundred years ago people wouldn’t take an elevator without an operator, they were scared about pushing the buttons… 25 to 30 years from now, our grandchildren will look back at our society and feel mortified that there was a time when humans drove cars and caused so many accidents!

Let’s not exhaust our thinking and productivity worrying about the distant future, we have enough to do today, now and in the next few years. Every technological breakthrough creates positive and negative effects. AI plays potentially positive roles, but can also generate fake-news, can also launch new attacks on the foundation of our institutions. Let’s work on a new game-plan, a new strategic framework for society.

As a species, we can event remarkable things, and be extraordinarily creative, but we sadly lack a strategy for the future.

——————————

Interviewee biography

Born in Baku, Azerbaijan, in the Soviet Union in 1963, Garry Kasparov became the under-18 chess champion of the USSR at the age of 12 and the world under-20 champion at 17. He came to international fame at the age of 22 as the youngest world chess champion in history in 1985. He defended his title five times, including a legendary series of matches against arch-rival Anatoly Karpov. Kasparov broke Bobby Fischer’s rating record in 1990 and his own peak rating record remained unbroken until 2013. His famous matches against the IBM super-computer Deep Blue in 1996-97 were key to bringing artificial intelligence, and chess, into the mainstream.

Kasparov’s was one of the first prominent Soviets to call for democratic and market reforms and was an early supporter of Boris Yeltsin’s push to break up the Soviet Union. In 1990, he and his family escaped ethnic violence in his native Baku as the USSR collapsed. In 2005, Kasparov, in his 20th year as the world’s top-rated player, retired from professional chess to join the vanguard of the Russian pro-democracy movement. In 2012, Kasparov was named chairman of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation, succeeding Vaclav Havel. HRF promotes individual liberty worldwide and organizes the Oslo Freedom Forum. Facing imminent arrest during Putin’s crackdown, Kasparov moved from Moscow to New York City in 2013.

The US-based Kasparov Chess Foundation non-profit promotes the teaching of chess in education systems around the world. Its program already in use in schools across the United States, KCF also has centers in Brussels, Johannesburg, Singapore, and Mexico City. Garry and his wife Daria travel frequently to promote the proven benefits of chess in education and have toured Africa extensively.

Kasparov has been a contributing editor to The Wall Street Journal since 1991 and is a regular commentator on politics and human rights. He speaks frequently to business and political audiences around the world on technology, strategy, politics, and achieving peak mental performance. He is a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Oxford-Martin School with a focus on human-machine collaboration. He’s a member of the executive advisory board of the Foundation for Responsible Robotics and a Security Ambassador for Avast Software, where he discusses cyber security and the digital future. Kasparov’s book How Life Imitates Chess on strategy and decision-making is available in over 20 languages. He is the author of two acclaimed series of chess books, My Great Predecessors and Modern Chess. Kasparov’s 2015 book, Winter Is Coming: Why Vladimir Putin and the Enemies of the Free World Must Be Stopped is a blend of history, memoire, and current events analysis.

Kasparov’s next book is Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins. (May 2017) It details his matches against Deep Blue, his years of research and lectures on human and machine competition and collaboration, and his cooperation with the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford. He says,

“AI will transform everything we do and we must press forward ambitiously in the one area robots cannot compete with humans: in dreaming big dreams. Our machines will help us achieve them. Instead of worrying about what machines can do, we should worry more about what they still cannot do.”

May 22, 2017

Grandmasters vs. Gigabytes | review of “Deep Thinking” by Robin Hanson | WSJ

By Robin Hanson

May 18, 2017

Garry Kasparov on a television monitor May 1997, at the start of the sixth and final match against IBM’s Deep Blue computer. PHOTO: AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

Remember those inspiring but tragic tales of humanity’s last cashiers and travel agents struggling against the relentless robots coming to take their jobs? The thrill of competition, then the agony of defeat? Me neither. Few readers would be interested in such stories anyway. But world chess champion Garry Kasparov is hoping that you’ll want to hear his own account of a man being beaten by machines.

On May 11, 1997, he became the first world chess champion to be beaten by a computer, IBM ’s Deep Blue. Though he had won against the computer easily just a year before, this time a greatly improved opponent defeated him and, at times, broke his composure. In a rare blunder, he even resigned from a position that would have led to a draw. Mr. Kasparov says that his book “Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins” contains the first account of this match “that has all the facts and the only one that has my side of the story.”

Though he had previously voiced suspicions that Deep Blue’s creators cheated by spying on his private team discussions, he now doubts this occurred. After all, he’s seen how computers have continued to improve: Today they play chess so well the best humans don’t stand a chance. But this does not make humans superfluous. More people play chess well than ever before; computer aids help players learn faster; and computer-human chess teams have become the basis of an exciting new sport.

Press to order on Amazon Now!

With the benefit of time and perspective, Mr. Kasparov can admit his experience with Deep Blue says little “beyond what we already knew was inevitable, that smarter programs on faster machines would beat the human world champion sometime around the year 2000.” Stepping back further, he observes that, when it comes to computer-human competition, the consistent pattern is “thousands of years of status quo human dominance, a few decades of weak competition, a few years of struggle for supremacy. Then, game over.”

Though Mr. Kasparov writes knowledgeably about the computers that beat him, when he turns toward prediction-making he is prone to over-generalize from these experiences to make statements about all computers everywhere and forever. He says things like “A computer won’t tire . . . or [get] distracted” and “computers . . . don’t understand general concepts” or know how to bluff. Well, today computers don’t, but tomorrow they might. “Machines cannot dream,” he writes, “not even in sleep mode.” Again, true today, but who can say how far computers might improve?

Mr. Kasparov’s most flowery and emotional language arises when addressing the issues in his subtitle. “To keep ahead of the machines,” he writes, “we must not try to slow them down because that slows us down as well.” Though I tend to agree with such claims, they are more preached than argued in this book, and there’s not much analysis behind Mr. Kasparov’s predictions, or his assertion that “machines will . . . [take] over the more menial aspects of cognition, . . . elevating our mental lives toward creativity, curiosity, beauty, and joy.”

On other topics, Mr. Kasparov makes many thoughtful observations. Eager for big education reforms, he laments that we often avoid big innovations, and instead pretend that small ones are big. He perceptively observes that “many things we call innovations are little more than the skillful accumulation of many little optimizations.” And, he notes, “the potential for change is much greater than our appetite for it.”

Interestingly, Mr. Kasparov also believes that there’s nothing special about chess as a metaphor for other activities or as an intelligence test for humans or machines. It was a big mistake, he thinks, for early computer researchers to expect “that if a machine could be taught to play chess well, surely the secrets of human cognition would be unlocked at last.” Specialized chess machines can be a fine sport, but the quest to understand human general intelligence should invest elsewhere: Most things our minds do aren’t much like playing chess.

Given his history, you might expect Mr. Kasparov to sell his story as an aid to seeing how computers will come for your job. “Every profession will eventually feel this pressure,” he says. But his advice to workers runs more to timeless practical maxims, such as “hard work is a talent,” “a bad plan is better than no plan” and “if you change your strategy all the time you don’t really have one.” More than any such specific observations, however, what I value most in this book is Mr. Kasparov’s own example. He sets himself forward as an intelligent, honest and self-critical person, working hard to adapt to and understand his world. The author admits to being a sore loser and apologizes for not being gracious after the Deep Blue defeat. He worries that his age and success limit his openness to changing his thinking, about chess and more, and sees little point in debating the meaning of “intelligence.”

I’ve always been a bit skeptical of the high status of chess champions, whom many consider intellectuals (rather than, say, sports stars). But in “Deep Thinking,” Mr. Kasparov has changed my mind. He praises Mikhail Botvinnik, the founder of the Soviet chess school where he trained, for practicing an “intense regime of self-criticism.” Chess champions are rewarded for brutal honesty about their habits and strategies. If only most tenured professors and business executives were this conscious of their limitations and blind spots.

“Few young stars in any discipline are aware of why they excel,” Mr. Kasparov writes. Like Mr. Kasparov, I don’t know why he was great. But I know now why I’m glad we have him. We need at least a few of our most celebrated minds to be this intellectually honest with themselves, and with us.

Mr. Hanson is a professor at George Mason University and the author of “The Age of Em: Work, Love, and Life When Robots Rule the Earth.”

May 18, 2017

Garry Kasparov : What Constitutes Intelligence | TechCrunch May 17, 2017

Garry Kasparov talks to TechCrunch writer Devin Coldewey about what separates human from machine minds, the problems with relying on AI, and his thoughts on Putin’s regime.

Garry Kasparov's Blog

- Garry Kasparov's profile

- 558 followers