Garry Kasparov's Blog, page 46

January 28, 2018

BBC Radio Interview | Jan 28th, 2018

PRESS TO LISTEN TO BBC RADIO INTERVIEW

Here’s the link to my Desert Island Discs on @BBCRadio4 appearance today, free to listen worldwide. Mostly music, movies, theater, but of course cannot escape politics.

January 22, 2018

KASPAROV REPLAYS HIS FOUR MOST MEMORABLE GAMES | Jan 19th, 2017

The grandmaster Garry Kasparov, considered by many to be the greatest chess player of all time, replays some of his most unforgettable games. He relives both the happiest and the most painful moments of his career.

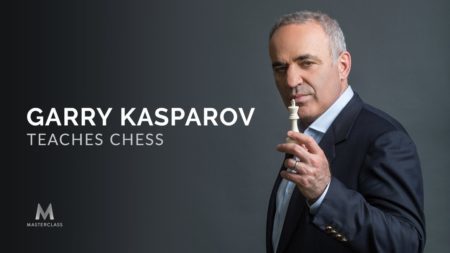

Garry Kasparov now teaches chess on MasterClass

January 18, 2018

Garry Kasparov answers chess questions from Twitter | Jan 16th, 2018

Chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov uses the power of Twitter to answer some common questions about the game of chess. Why do chess players point at pieces with their middle finger? Why does the knight move the way it does? What’s the more valuable piece, the knight or the bishop? Garry answers all these questions and more!

Check out Garry’s MasterClass on chess

January 17, 2018

In Conversation with Bill Kristol | Jan 14th, 2018

In his most recent appearance on Conversations, former world chess champion and human rights activist Garry Kasparov discusses artificial intelligence and the political and social implications of it. Drawing on his recent book Deep Thinking, Kasparov outlines what he considers the potential of new technologies built on “machine learning.” Kasparov explains why free societies must prioritize technological progress and embrace the challenges associated with innovation. Finally, Kasparov considers the new artificial intelligence chess program, AlphaZero—what we can learn from it about chess, as well as the relationship between humans and machines.

This Conversation and all previous releases are also available as audio podcasts on iTunes and Stitcher.

To view the other Conversations that have been previously posted, click here.

January 12, 2018

Garry Kasparov and the game of artificial intelligence | Innovation Hub Podcast | Jan 5th, 2018

“From the beginning of the computer era, it was a belief that chess could serve as the ultimate test for machine intelligence,” Kasparov says. “And the game of chess has always been seen as the nexus for human intelligence. So when a machine faced a human in chess and won this battle … it could definitely be a revolutionary moment.”

Immediately after the match, Kasparov was bitter. But in the 20 years since, the chess legend has warmed to his place in history. In his new book, “Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins,” Kasparov discusses the story of that match and its place in the broader narrative of artificial intelligence.

“If I had to think whether this was a blessing or a curse that I became world champion when machines were really weak, and I ended my professional career when computers were unbeatable, I think it’s more like a blessing,” Kasparov says. “I was part of something unique.”

Kasparov has become even more involved in artificial intelligence over the years. He came up with a concept he calls “advanced chess,” where a human and a computer team up to play against another human and computer. Kasparov says this situation is mutually beneficial: The human player has access to the computer’s ability to calculate moves, while the computer benefits from human intuition.

And chess isn’t the only avenue for this human-machine partnership. Kasparov says this sort of cooperation is possible in everything from diagnostic medicine to manufacturing.

“You’d rather have an experienced nurse working with an algorithm rather than a top professor who might be tempted to challenge a machine’s assumptions,” Kasparov says.

But not everyone shares Kasparov’s optimistic view of a machine-filled future. There are concerns that robots will replace humans in the workforce. Machines are viewed as a looming threat to jobs and the economy.

These days, Kasparov isn’t ruffled by computers. He says humans have always developed machines. And despite concerns throughout history, we have always managed to adapt.

“The difference today is that machines are going after people with college degrees, political influence and Twitter accounts,” Kasparov says. “But this is normal. Any industry that isn’t under pressure from technology is in stagnation.”

That includes the technology industry itself. Last year, DeepMind’s AlphaZero AI beat Stockfish, formerly the world’s top-ranked chess engine. It started with no prior knowledge of chess and needed only four hours of self-training.

A version of this story originally appeared on Innovation Hub.

January 10, 2018

Kasparov Exclusive: MASTERCLASS | Chess.com | Jan 10th, 2018

READ ORIGINAL INTERVIEW AT CHESS.COM

Watch Kasparov Exclusive: His MasterClass, St. Louis, AlphaZero from Chess on www.twitch.tv

Garry Kasparov had a busy spring and summer of 2017 in which he recorded his MasterClass and then participated, after a 12-year absence from competitive chess, in the Saint Louis Rapid & Blitz tournament. While he’s been on television much recently to discuss politics, his passion is still the game that made him famous. In an exclusive interview for Chess.com, he speaks about all manners relating to chess.

The interview was conducted in late December in Kasparov’s new office atop a New York City high-rise in midtown Manhattan. He was clearly excited, as afterward h, had planned to show two chess positions left on the MasterClass cutting room floor, but he ended up analyzing two of his games, and showing two of his favorite studies (those videos to follow soon on Chess.com).

The first topic was Kasparov’s MasterClass, and how he prepared for the production. He had many positions, games, and studies that were left out of the final product, and those factored into the discussion as well.

He said he was “quite pleased with the final product,” but it was not an easy task:

I have to confess that I wasn’t sure from the beginning. I watched, of course, Steve Martin, Serena Williams, I could see the highest quality of production… But how to squeeze my knowledge of the games of chess, my experience, my passion for the game in six, seven, eight hours, whatever will be the final product? And also, what is the target audience?

There are so many people that like to hear what Garry Kasparov is going say about chess and this crowd will be ranging from total beginners to very decent, strong players. I’ve been contemplating my message, how could I create something that could be of interesting for as large an audience as possible.

I decided that it’s not about being very precise with some tactical tricks, even strategical concepts because there are so many of them. It’s just trying to give the gist of what I think is important for people to make progress.

Kasparov mentioned that an Elo level of 1300-1700 was “potentially the core audience” but one thing was central for him.

The most important task for me was to communicate my love and passion for the game, and also to demonstrate the beauty of the game.

Garry Kasparov in his Manhattan office. | Photo: Mike Klein/Chess.com.

In line with his recent book on AI, Kasparov denies that computers are only harmful to the game:

Usain Bolt is not going to compete with Mercedes Benz. Even though computers are now much stronger in chess or virtually in any other video or board game, it doesn’t stop humans from competing against each other but most importantly, to enjoy the beauty of the game. And sometimes you can use machines to help you to create beautiful studies. Many of the best studies in the last decade have been created with the assistance of the computer. I wanted to present this multidimensional beauty of the game.

Even now, 12 years after I left professional chess, I haven’t lost my ability to be mesmerized by some of the great positions. There is still plenty in the game of chess to be discovered. Any new step in revealing the secrets of the game, with new machines, new computers, new engines, I take as positive not negative because it helps me to understand this game deeper. The deeper we understand the game, the more we can enjoy it.

Kasparov preparing a video for Chess.com on his game with Veselin Topalov, Linares 1999. | Photo: Mike Klein/Chess.com.

The preparation for the lessons wasn’t easy.

It was challenging both physically and psychologically. These days I am not used to such an intense program. That was one of the problems I experienced in St. Louis: It’s very difficult to change the algorithm that is working inside your brains to help you to meet the challenge you’re dealing with. What helped me is that I enjoyed it myself.

Whether it is working on MasterClass, analyzing or playing, Kasparov will always be passionate about chess. He noted:

Everyone who once made it to the very top, couldn’t make it without passion.

Asked whether the filming of MasterClass inspired him to come back to competitive chess, he said:

Yes, it did. It’s not just the MasterClass itself but also the environment of St. Louis. It’s a place where I feel that playing chess is fun. While I was quite skeptical of my chances of playing well, it was hard to resist this temptation. After a few rejections of potential other wild cards to join the Grand Prix [sic] and an open invitation from Rex Sinquefield, how could I say no?

Kasparov: “Everyone who once made it to the very top, couldn’t make it without passion.” | Photo: Mike Klein/Chess.com.

But for this, second major event chess in 2017 for Kasparov, the preparation wasn’t great.

I knew it would require a total change of my regime and I couldn’t make it. I still had to fly back and forth, I had so many arrangements, like speaking at DevCon in Las Vegas and then I had to go back to my family in Europe, so it was not a preparation that Garry Kasparov 20 years ago would approve. In order to compete seriously against the world’s top players I probably needed two months of full concentration, maybe staying in St. Louis or even staying in Croatia, but just doing nothing else but chess, thinking about chess, and washing out everything else. It was not possible. I probably had a few weeks of preparation, just playing a few training matches. I had some ideas.

Every time I go back to St. Louis, the summer of 2017, think about some of these games, it’s almost a nightmare because I got very good positions and there were several games where part of the game I played like Garry Kasparov but I don’t want to think what happened in the rest of the game!

Realistically speaking, with some good preparation and with my site of mind being focused on the game I would definitely make top five… By the way, even in this horrible tournament for me, I was just one point away from top five, so maybe I could make top three. That would be realistic. Having plus one, plus two in rapid and plus three in blitz is not beyond my ability to achieve. But at the end of the day, it was not about scoring these points, it was about having fun for myself and also sharing this fun with the rest of the crowd.

Kasparov has looked at his games in St. Louis—not too deeply, and with a computer. He said he noticed the same pattern; playing well, getting a good position, and then a blackout.

There was not much to learn from the chess angle; it was more about psychology. It’s something I have to accept as the very sad reality: I am no longer just to play, even in rapid, games with the same level of concentration and dedication as before.

Maybe somehow it was a conspiracy of the game of chess against me because it was probably wrong of me to go back after 12 years of inactivity and also not concentrating on the tournament, somehow it’s a punishment. If you want to play well, you have to make it a priority. A message from Caissa: You don’t want to concentrate? Fine, we’ll teach you a lesson.

“It was not a preparation that Garry Kasparov 20 years ago would approve.” | Photo: Mike Klein/Chess.com.

On the question that’s on everyone’s lips — Will we see him in a rated event ever again?

Right now I don’t think about it. I doubt it will be next year. I cannot afford to do it again the same way as I did in 2017. If I do it again, it should be a test, what I really can do if I spend a certain amount of time to concentrate and prepare myself for this challenge of facing top players. I am not sure I have this time available. I wouldn’t say no, no, no, no, but it’s unlikely.

Kasparov called Alphazero “good news for chess.”

We can learn a lot from the way AlphaZero plays. What I understand is that it establishes it’s own skill of evaluation, so set of priorities, which is quite a unique accomplishment because typically every program has this set of priorities and it’s not flexible. They maybe make slight alterations but in general, they have to stick with the original numbers that are attached to each priority in this evaluation mechanism. AlphaZero, after playing millions and millions of games, came up with its own set of values.

About Alphazero crushing Stockfish, he said:

What was most amazing was, just statistically, it’s the white and black. AlphaZero was totally deadly with white while with black it was winning but by a very small margin. Does it tell us that we misunderstand the value of the first move? There’s still a lot to learn.

We’d also like to take the opportunity to show an “exclusive” (as in: not yet published) recent game by Kasparov, from a simul in Zagreb, late December 2017. It was sent to us by Kasparov’s aide-de-camp Mig Greengard, who added the comments as dictated by Kasparov himself. Black is Srdjan Darmanović, the foreign minister of Montenegro and a big chess fan who got up to a rating of around 2200 when he still played actively.

December 29, 2017

‘Machines reach the level that is impossible for humans to compete’ | Business Insider | Dec 29th,2017

by Jim Edwards

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE AT BUSINESS INSIDER

Chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov sat down with Business Insider for a long discussion about advances in artificial intelligence since he first lost a match to the IBM chess machine Deep Blue in 1997, 20 years ago.

He told us how it felt to lose to Deep Blue, and why the human propensity for making mistakes will make it “impossible for humans to compete” against machines in the future.

We also talked about whether machines could ever be programmed with “intent” or “desire,” to make them capable of doing things independently without human instructions.

And we discussed his newest obsessions: privacy and security, and whether — in an era of data collection — Google is like the KGB.

LISBON — Garry Kasparov knew as early as 1997 — 20 years ago — that humans were doomed, he says. It was in May of that year, in New York, that he lost a six-game set of chess matches against IBM’s Deep Blue, the most powerful chess computer of its day.

Today, it seems obvious that Kasparov should have lost. A computer’s ability to calculate moves in a game by “brute force” is infinitely greater than a human’s.

But people forget that the Deep Blue challenge was a set of two matches, and Kasparov won the first set, in 1996, in Philadelphia. In between the two matches, IBM retooled its machine, and Kasparov accused IBM of cheating. (He later retracted some of his accusations.)

In fact, Kasparov could have won the second series had he not made a mistake in game 2, when he failed to see a move that could have forced a draw. Deep Blue also made a mistake in game 1, which, at the time, Kasparov wrongly put down to Deep Blue’s “superior intelligence” giving it the ability to make counterintuitive moves.

Nonetheless, in a conversation with Business Insider at Web Summit in Lisbon this year, Kasparov said that was the point at which he first realised that humans were “doomed” in the field of games.

As long as a machine can operate in the perimeter knowing what the final goal is, even if this is the only piece of information, that’s enough for machines to reach the level that is impossible for humans to compete.

“I could see the trend. I could see that it’s, you know, a one-way street. That’s why I was preaching for collaboration with the machines, recognising that in the games environment humans were doomed. So that’s why I’m not surprised to see the success of AlphaGo, or Elon Musk’s Dota player AI [an AI player for the video game Dota 2], because even with limited knowledge that these machines receive, they have the goal. It’s about setting the rules. And setting the rules means that you have the perimeter. And as long as a machine can operate in the perimeter knowing what the final goal is, even if this is the only piece of information, that’s enough for machines to reach the level that is impossible for humans to compete,” he says.

Kasparov has written a book on AI, titled “Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins.” He has also currently an ambassador for Avast, the digital security firm.

Our first question was about “brute force,” and whether AI has moved beyond the problem of being reliant on vast databases to make choices instead of real “thinking” or “learning.”

“In the territory of games where the machine prevails because humans make mistakes.”

World chess champion Garry Kasparov studies the board shortly before game two of the match against the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue. This was only the second time in history that a computer program has defeated a reigning world champion in a classical chess format. The Russian grandmaster, who won game one May 3, lost game two after 45 moves and 3 hours and 42 minutes of play. Kasparov will play six games against Deep Blue in a re-match of their first contest in 1996.Reuters

Jim Edwards: You once said of artificial intelligence, we’re “in the territory of games where the machine prevails because humans make mistakes,” implying that AI’s main advantage was only that humans commit errors and machines do not. Is that still true?

Garry Kasparov: Human nature hasn’t changed since I said it. Humans are poised to make mistakes because we – even the best of us, in chess or in golf or in any other game – we cannot have the same steady hand as a machine has.

JE: Does the AI advantage consist only of mere consistency? That it will not make a mistake?

GK: I want to understand the difference between what [US mathematician Claude] Shannon classified as type A and type B machines. So the type A brute force type machines – it’s brute force and some algorithm. Might be something that you may call AI, because it resembles the way humans make decisions. By the way, all the founding fathers of computer science, like Shannon, [Alan] Turing, [Norbert] Weiner, they all believed that real success, the breakthrough, would be achieved by type B machines, human-like machines.

“Consistency is what is deadly for humans, because even the best of us are not consistent.”

Noam Galai/Getty Images for TechCrunch

JE: Would those human-like machines make mistakes?

GK: All machines make mistakes, don’t get me wrong. Because even when you look at the most powerful type A machines, the brute force, they cannot cope with everything – Deep Blue was a monster in speed in 1997, making 2 million positions per second. But the number of legal moves in a game of chess is 10 to the 40th power. That’s why it’s not about the mass of speed, it’s about certain assessments that the machine has to make just by moving from point A to point B. Machines are not prophets, machines can solve a game or goal. But it’s not about solving, it’s about winning. And that’s why machines can also make mistakes, but when you look at the average quality of the moves it’s fairly consistent. So consistency is what is deadly for humans, because even the best of us are not consistent. When you look at the top games played by the best players in a world championship match, you still find that in all the games there are – not blunders or mistakes, but obvious inaccuracies.

“It’s, you know, a one-way street. That’s why I was preaching for collaboration with the machines, recognising that in the games environment humans were doomed.”

Garry Kasparov and Business Insider’s Jim Edwards talking at Web Summit in Lisbon, in November 2017.Avast

JE: One example you write about is that in chess, humans really dislike giving up their queen, because it is the most powerful piece on the board, even when doing so is advantageous.

GK: If you’re talking about professional players they do whatever it takes to win. If we talk about top, top, top-level chess, it’s still not free from inaccuracies caused by the fact that players can get tired, they can lose their vigilance. Psychologically, when on the winning side, you think OK, the game is over so you can be relaxed. While in the human game it doesn’t matter since the favours are always being returned. Facing a machine – you will be out of business quickly. That’s why every closed system, and games are closed systems, automatically give machines an upper hand.

Today machines are absolutely monstrous.

I knew it since 1997. When you look at the absolute strengths of chess computers, Deep Blue was relatively weak by modern standards. Today machines are absolutely monstrous. They are much much stronger than Magnus Carlsen, and a free chess app on your mobile device is probably stronger than Deep Blue. I could see the trend. I could see that it’s, you know, a one-way street. That’s why I was preaching for collaboration with the machines, recognising that in the games environment humans were doomed. So that’s why I’m not surprised to see the success of AlphaGo, or Elon Musk’s Dota player AI [an AI player for the video game Dota 2], because even with limited knowledge that these machines receive, they have the goal. It’s about setting the rules. And setting the rules means that you have the perimeter. And as long as a machine can operate in the perimeter knowing what the final goal is, even if this is the only piece of information, that’s enough for machines to reach the level that is impossible for humans to compete.

“AlphaGo destroyed best Go players and then AlphaGo Zero, that had no information except the rules, destroyed AlphaGo. For me, it just shows how miserable the human knowledge of the game Go is. Go is very complex.”

AP

JE: What did it feel like to lose to Deep Blue?

GK: Losing is always bad. So it’s for me, I mean bad feelings. For me, it was just a first loss in the match, period. Not machine, just in chess. And in my book Deep Thinking I confess a few times I was a sore loser and very upset and I had all the criticism about the way IBM organised the match. I am still sticking to some of my criticism, there I gave in my book a lot of credit to IBM’s scientific team. It’s water under the bridge already.

JE: It’s a moment in history …

GK: It’s a moment in history though it was a brute force, not a human-like machine, a type B machine, that supposedly had to triumph in the game of chess. But as we discovered a game of chess was vulnerable to very powerful machines with sufficient algorithms and bigger databases, and very high-speed processors. So when you look at Go [the game], it’s already a different kind of machine, this is a deep learning programme. So it’s not that machine that relies on heavily or exclusively on brute force. It’s still brute force but you have elements of deep learning.

And while many people are just very impressed that AlphaGo destroyed the best Go players — and then AlphaGo Zero, that had no information except the rules, destroyed AlphaGo — for me, it just shows how miserable the human knowledge of the game Go is. Go is very complex. What the best Go players know about Go today probably reflects what the best chess players knew about chess 200 years ago. And if you show the games, modern chess games, to the greatest chess players of the nineteenth century, they will be shocked because that will go way beyond their imagination.

But let me go back to this point. It’s a closed system, so in any closed system, machines will always dominate. Anything that is quantifiable machines will do better than humans and we should not make an assumption that you could automatically transfer the knowledge from the closed system to an open-ended system.

“Machines can solve any problem but they just don’t know what problem is the relevant one. ”

JE: In terms of deep learning where the machine has to learn on its own, it’s not just brute force, you’ve talked about how hard it is to give a machine a purpose – machines don’t have an intent. They do what you tell them. The machine itself doesn’t desire.

GK: It’s about identifying the goal.

JE: How important is intent in AI in the future? Is it possible to give an artificial intelligence an intent?

GK: Intent starts with a question, and machines don’t ask questions. Or to be precise, they can ask questions but they don’t know what questions are relevant. It’s like a limitation, because a machine doesn’t understand the concept of diminishing returns. It can go on and on. So the moment there’s an intent, the purpose, you get this wall that a machine reaches and stops. So I see in the foreseeable future just very little chance, if any, for machines to come up with an intent. I think it contradicts the way machines operate, because machines these days know the odds, they can work with patterns, but still “intent” — this is what transfers open-ended systems to closed systems. And you have to understand what is relevant. [I did a lecture once] and I was followed by a professor from Cornell and she talked about it, and she said, “Machines can solve any problem but they just don’t know what problem is the relevant one. ”

“As someone who grew up in the Soviet Union, I know enough about dictators and the way they operate, how do we deal with the fact that we are willingly conceding so much personal data out of convenience?”

JE: Why is security such a big deal for you?

GK: It brings together certain elements of my life. So the key interests of my current life. It’s connected to AI and technology, but it’s also about individual rights and I’ve been warning for years about the danger of modern technology being used by bad guys to undermine our way of life. And now I think it’s this. We are facing a big challenge. Let’s set aside Putin and Kim Jong un and all these terrorists and dictators. Our society is undergoing a massive change because of technology. And there are many issues that I’m raising in these blogs for instance, like free speech versus hate speech. We used to live in the environment where we just could separate good from bad. Now we live in an environment where it’s, unless you regulate it heavily, which I don’t like, so it’s impossible to stop the flood of negative information, something we don’t want to see. So we just have to make some tough choices. So it’s how we operate in the era of fake news, troll factories, and malicious players. But also there’s a big issue, so I think it’s important for me as chairman of the Human Rights Foundation and as someone who grew up in the Soviet Union, so I know enough about dictators and the way they operate, how do we deal with the fact that we are willingly conceding so much personal data out of convenience? Because we want to use all these benefits, not recognising that if you’re connected to the world, your information will be collected. What will be the outcome of this enormous data collection about individuals, and it’s information being stored within multinational giants, corporations? I’m just trying to find a rational, not solution, but it’s a suggestion that we still have to see the difference between Google data collection and the KGB. But even if it’s Google, it’s an American company, but how you make sure that this information is not used to harm individuals? So those are issues that are important for me. And also Avast is actively engaged in using AI in protecting individual customers from all sorts of malware. And while I’m not an expert in technology, I feel strongly that this is what is to be done. So it’s protecting individuals against all sorts of threats they’re dealing with in this exciting, modern but dangerous world.

December 22, 2017

Seasonal Greeting from Garry Kasparov

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,

Another year is coming to a close. The conventional wisdom is that 2017 was a tumultuous year, an annus horribilis full scandals, disasters, and a negative trend that we can only hope to reverse in the coming year. It’s not just my contrarian nature that makes me want to push back against this dismal narrative. I am not going to deny there have been many challenges and outright disasters in the past year, of course. After all, the first step in making things better is to make an honest evaluation. There are, however, plenty of silver linings to be found, as well as some inarguably positive developments.

This is more of a personal message than a global ‘Year in Review’, but I want to offer some encouragement to the many people who are depressed or even panicked about the global state of affairs, especially considering the occupant of the White House. Donald Trump is unstable, autocratic by nature, and obsessed only with his own image; his presidency threatens to unbalance decades of relative post-Cold War stability. But if someone like Trump can shake the democratic foundations of the United States, how stable were those foundations? As I warned back in February, Trumpism is exposing the many cracks that existed in the separation of powers, conflicts of interest, the relationship of the free press with politics and business, and the deep divides separating many Americans on social and economic issues. This is very dangerous, yes, but it’s also a vital wake-up call to repair and heal those institutions and divisions.

All those issues already existed and were slowly getting worse under the radar. Thanks to Trump, Americans and people in many other democratic nations are actively fighting back against the threat of anti-democratic forces from abroad and in their own countries. In this regard, the US investigation into Russian influence on the 2016 election is important. Will it be allowed to conclude? Will action be taken against Putin , or others in the Trump administration? It’s not just important for itself, but as a test of the system’s ability to defend itself.

I’m also optimistic because there is no benefit to being otherwise! Believing in positive change, and taking action to create it, is how we get others to accompany our efforts and make it real. This is also true in tech, where I believe strongly in the self-fulfilling prophecy of our innovations like artificial intelligence. If we believe things will go well, we are more likely to invest in the future and take more risks—exactly the behavior that make things go well!

It has been a mixed blessing to become a sort of visiting expert not on chess, or even human-machine or Russia or decision-making, but as the voice of experience in how a democracy becomes an autocracy.

That is, I’m glad people are listening to me, but it’s frightening that such expertise is needed and relevant. No, I don’t think America is going to become a dictatorship the way Putin destroyed Russian democracy. But the lessons of the fragility of democracy must not be forgotten. In the words of former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, “The practice of democracy is not passed down through the gene pool. It must be taught and learned anew by each generation of citizens.”

2017 was a very full year for me professionally and personally. I logged a record number of hours in the air, which is quite something considering how much I always travel. This perpetual motion was mostly the result of rising interest in my areas of interest: Russia, human rights, and human-machine collaboration. The Human Rights Foundation, of which I am chairman, hosted our first New York City edition of the Oslo Freedom Forum, celebrating in both events the work of dissidents against authoritarianism around the world.

In February, my book Deep Thinking was published by Public Affairs. It focuses on the human-machine relationship, grounded in my own experiences. It was timed for the 20th anniversary of my famous rematch with the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue in 1997, but it turned out to be ideally timed for the huge wave of interest and real-world impact of artificial intelligence—or, as is more accurate in many cases, augmented intelligence. I was flattered by the book’s critical success , especially the gracious reception by many experts in the field whose work I have learned so much from. Google DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis, creator of the groundbreaking AlphaGo and AlphaZero machine learning systems, has been very supportive and hosted me at Google HQ in London for a talk about our shared passion for the power of machine learning to transform our world—and how chess and other games are still an ideal laboratory.

In February, my book Deep Thinking was published by Public Affairs. It focuses on the human-machine relationship, grounded in my own experiences. It was timed for the 20th anniversary of my famous rematch with the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue in 1997, but it turned out to be ideally timed for the huge wave of interest and real-world impact of artificial intelligence—or, as is more accurate in many cases, augmented intelligence. I was flattered by the book’s critical success , especially the gracious reception by many experts in the field whose work I have learned so much from. Google DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis, creator of the groundbreaking AlphaGo and AlphaZero machine learning systems, has been very supportive and hosted me at Google HQ in London for a talk about our shared passion for the power of machine learning to transform our world—and how chess and other games are still an ideal laboratory.

Consulting firms and financial asset companies are rushing to stay ahead of this wave, and I’ve had many opportunities to serve as a sort of translator and evangelist for the positive future of intelligent machines. My business lectures have always focused on human strategic thinking, and that is still true. The difference now is that working with algorithms and big data is an essential element of that strategy for nearly every business. At every event, I hear from experts in other fields about how increasingly vital the theme of human-machine collaboration is, from medical diagnosis to asset management to cyber-security. I’ve learned so much in the year since Deep Thinking came out that I almost feel like I could write a sequel immediately.

Consulting firms and financial asset companies are rushing to stay ahead of this wave, and I’ve had many opportunities to serve as a sort of translator and evangelist for the positive future of intelligent machines. My business lectures have always focused on human strategic thinking, and that is still true. The difference now is that working with algorithms and big data is an essential element of that strategy for nearly every business. At every event, I hear from experts in other fields about how increasingly vital the theme of human-machine collaboration is, from medical diagnosis to asset management to cyber-security. I’ve learned so much in the year since Deep Thinking came out that I almost feel like I could write a sequel immediately.

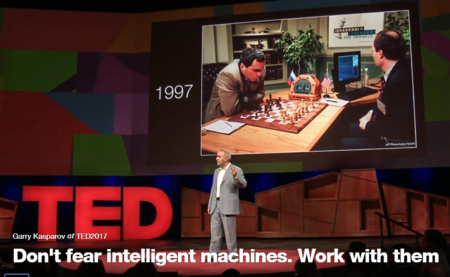

At several events for McKinsey, I discussed the moment at which humans must go from experts to operators in order to gain the greatest benefit from intelligent machines. In Helsinki, Zurich and Singapore for Management Events, I talked about how people’s role is to define the problems while our increasingly smart algorithms then solve them. In my TED Talk and at DefCon I spoke about the need for more tech disruption, not less, so that we can stay ahead of our machines by coming up with more challenges, more things we don’t know how to do. In every case, I emphasize the eternal value of human creativity and purpose. I may have been the first knowledge worker to be surpassed by a machine, but I’m here to say that this can be a good thing for every industry!

I made several appearances with a specific focus on security as part of my continuing partnership with Avast Software, a premier digital security firm. As a “Security Ambassador” for Avast, I’ve also been blogging regularly about the nexus of technology, privacy, security, AI, and human rights. I’m impressed at Avast’s interest in participating in these complicated conversations. They realize, as I do, that tech isn’t good or evil, but agnostic , and there will always be threats and arguments about right and wrong. The goal is to keep having this conversation and to thereby create better humans, not just smarter machines.

I made several appearances with a specific focus on security as part of my continuing partnership with Avast Software, a premier digital security firm. As a “Security Ambassador” for Avast, I’ve also been blogging regularly about the nexus of technology, privacy, security, AI, and human rights. I’m impressed at Avast’s interest in participating in these complicated conversations. They realize, as I do, that tech isn’t good or evil, but agnostic , and there will always be threats and arguments about right and wrong. The goal is to keep having this conversation and to thereby create better humans, not just smarter machines.

That statement has been my mantra as a member of the executive board of Noel Sharkey’s Foundation for Responsible Robotics . The focus here has been on putting pressing issues in front of governmental bodies before there is a crisis. For example, autonomous weapons systems encapsulate every “Terminator” nightmare scenario in the real world. I’m not in favor of dystopian fear-mongering about “killer AI,” of course, but policy and public debate must accompany the growth of any new technology, as I said to an OSCE conference on the topic.

A new challenge for me was the production of my online video chess Master Class, which was just released this week. I’ve had many invitations to produce a chess course over the years, but this was the first time I could see that the presentation and quality were high enough to contribute my name and many days of exhausting effort. It’s a new way to promote the great game that gave me so much, and I must say that the results exceeded my high expectations. You can check out the trailer if you doubt my words.

A new challenge for me was the production of my online video chess Master Class, which was just released this week. I’ve had many invitations to produce a chess course over the years, but this was the first time I could see that the presentation and quality were high enough to contribute my name and many days of exhausting effort. It’s a new way to promote the great game that gave me so much, and I must say that the results exceeded my high expectations. You can check out the trailer if you doubt my words.

Speaking of promoting chess, the Kasparov Chess Foundation celebrated its 15th anniversary with a small event for supporters and players. Our goal from the beginning has been to promote chess in the education system, and that continues to be an expanding success. Along with the Saint Louis Chess Club and Scholastic Center , KCF also supports the training of the top junior players in the United States, and the results have been incredible, with multiple medal winners.

I wish I could say the same about my own chess performance in 2017, but I’m afraid that the less said about my brief unretirement at the Saint Louis Rapid and Blitz tournament, the better. I was happy to help promote the great work Rex Sinquefield and his Saint Louis team do for chess, and in that regard, my participation was a real success. And since this is my message, I’ll leave it at that!

Best wishes to all from the entire Kasparov family. Let 2018 be the year in which we apply the many hard lessons we learned in 2017.

NPR | Here & Now | Dec 20, 2017

In hour two of Here & Now’s Dec. 20, 2017 full broadcast, political analysts John Brabender and Jamal Simmons discuss the implications of the recently passed Republican tax cut overhaul. Also former world chess champion and Russian pro-democracy activist Garry Kasparov discusses why he believes the Trump White House is in the early stages of “threatening the very foundation of this republic.” And, we take a look back at the deadliest pandemic in recorded history: the 1918 flu pandemic.

Listen· 41:55

Garry Kasparov warns of Putin’s aims | Morning Joe | MSNBC | Dec 20th, 2017

Garry Kasparov of the Human Rights Foundation discusses Vladimir Putin’s impact on the United States, and why he’s a ‘merchant of doubts.’ Kasparov also discusses his first online chess course.

Garry Kasparov's Blog

- Garry Kasparov's profile

- 558 followers