Ed Gorman's Blog, page 84

July 10, 2014

SPOUSES & OTHER CRIMES by ANDREW COBURN

Andrew Coburn was born May 1, 1932, in Exeter, New Hampshire, and has lived most of his life in towns outside Boston. Following U.S. military service, Coburn joined theEagle-Tribune of Lawrence, Massachusetts, which launched his career as an award-winning crime reporter and publisher of his own newspapers. He was granted the prestigious Eugene Saxton Memorial fellowship for young writers in 1965, and published his first novel in 1974. Since then, Coburn has gone on to be a New York Times bestselling author, been nominated for an Edgar award for Goldilocks — third in the Sweetheart Trilogy — has been translated into 14 languages, and has had three of his novels made into French films. The father of five, Coburn lives with his wife, Casey, in Andover, Massachusetts, deep in the New England suburbia he knows and writes about so incisively.

ForewordAbout Andrew Coburn by Rick Ollerman

It’s said that writers can be good at short stories or good at novels but rarely good at both; it’s said so often it could even be true. However we define novels—character studies on the way to climax and denouement, page-turning narratives of plot device, deeper studies of theme and insights into life and humanity, flat out mind-striking entertainment, whatever–they strive to entertain. As do short stories, but without the luxury or curse of length, subtext—the things that are said without being written—becomes a much more important tool for the author to master in order to make his point. In a short story, this comes faster and sharper than in a novel.Short stories may have more in common with poems than they do with novels. If a poem is a piece where every word must count, then every word wants to be the right word, the perfect word. A poem might be evocative, informative, sensual; it might be as alive as a single something that flares into existence, then disappears, leaving an imprint on the conscious mind. It might be a hummingbird that zooms past your head, there and gone, almost unrecognizable until that moment later when you realize what it was.Short stories can do that: evoke, stimulate; use not only the perfect word in its precise, perfect spot, but use characters as word poems unto themselves.

Andrew Coburn was born in Exeter, New Hampshire in 1932. He went into the Army out of high school at age 18, serving time in Frankfurt. After his time in the service, he earned a college degree and became an award-winning crime journalist in Massachusetts. He covered organized crime and for a while carried a hand gun after learning a contract had been put out against his life.He turned this experience to fiction. In 1965 he received the Eugene Saxton Fellowship—earlier recipients included James Baldwin and Rachel Carson—and published his first novel, The Trespassers, in 1974.Known for his haunting prose about crime in the towns outside of Boston, Coburn began a trilogy with the novel Sweetheart in 1985; continued in 1987 with Love Nest; and concluded with Goldilocks in 1989. Nominated for the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Allan Poe award for Best Novel, Goldilocks gave way to Black Cherry Blues, the third entry in James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux series. Burke, like Coburn, is known for the lyrical use of language and staggering sentences that transcend the genres—mystery; thriller; psychological suspense—that they fill in the marketplace. Whatever they write about, the work itself is beautiful, even in most cases where it involves a subject as ugly as crime.Author Ed Gorman says, “Andrew Coburn writes page-turners. A special kind of page-turner.” He also praises his “authenticity,” saying that “Andrew has BEEN THERE.” Of his most recent novel, 2006’s On the Loose, Gorman says:“I've been saying for years that the single most neglected major crime fiction writer in the United States is Andrew Coburn. And here he is with a new novel to prove me right again. I've spent two days trying to think of a tidy way to describe On the Loose and thus far my best shot is to imagine a collaboration between John D. MacDonald and Ruth Rendell. MacDonald for the page-turning excitement of following the most unique serial killer since The Bad Seed and Rendell for [the quirky characters].”Gorman continues. “And the writing itself. Coburn plays all the instruments in the orchestra… lyrical, funny, solemn, sarcastic, violent, terrifying and human in a way page-turners rarely are.”High praise indeed. If Andrew Coburn is one of the unrecognized gems of the literary world, he certainly leaves his mark on those who discover his work.

In addition to his “Sweetheart Trilogy,” Coburn’s No Way Home (1992) and Voices in the Dark (1994) form a duology: tales of small-town Bensington, Massachusetts, “under pressure,” says Publishers Weekly of the first, “from city and state politics.” Of the companion novel: “This slick, suspenseful thriller, the second appearance […] of James Morgan, police chief of the seemingly peaceful Boston suburb of Bensington, begins with a suspicious death—and, as luck would have it, a self-confessed murderer. […] A somber conclusion at a private care facility involves the abandoned elders of Bensington families and underscores the long line of loneliness and dreary existence often at the core of small-town life.”That last sentence leads us to one of the strengths of Coburn’s work. He looks at the quiet events below the surface of what appear to be typical American suburbs; he examines his characters deeply, and knows what moves them, makes them feel, imbues them with who they are.In Spouses & Other Crimes, the first short story collection of his long career, Coburn tips his novels over to tell stories, not of crime per se, but of their hurt. Indeed, in this case, the use of the word “crimes” in the title might be a euphemism for the word “pain.” The tales he tells here are of the different forms of despair and longing, typically quiet, some unrecognized by the characters themselves. Dig a bit, and we all know, to one degree or another, these feelings in ourselves.So these are not stories of the hunt for the solution to the dark and depraved. Here, the conflicts flare up between wants and desires and lives not yet turned true. The stories collected here originally appeared in various publications from 1964 through 2011; one, previously unpublished, appears here for the first time. If we look at the collection as the lifespan of a human being, the first story, “Charlie Judd,” centers on a twelve-year-old boy seeing his future in an encounter with a fifty-year-old man. It is a version of a certain kind of growing up; not troubled, exactly, but shadowed with omen and portent.The last story, “Plum Island,” tells of another such encounter, terminating the line begun with “Charlie Judd.” Two fishermen talk: one younger, well equipped; the other older, angling with old, inappropriate gear; and the difference speaks volumes.

Darkness arrives quickly. We can no longer see where we have cast our lines. Nearby a fish is making its final argument with a hook baited by one of the other fishermen .The old man wonders aloud about the guilt of a fish that gives itself up so easily.“Listen,” he says and tells me about the woman’s child, a boy of four, who buried a dead bird and exhumed it a day later, upset because it hadn’t risen. Then he talks about the woman’s face, which eventually gave out a silent message. “Ask me anything. I have no answers.”[…] He reels in his line. No bait left on the hook, which is how he wants it. He separates the pole into two pieces. His box of sandworms is mine if I want it. He must return to Boston. Here at Plum Island, where things become lost forever in the sand or washed away with the tide, the world is ageless, all of a piece, fish and fisherman one, the fishermen interchangeable, ghosts of other generations. He and I are one, our age difference blurred.

The first story is longer, the young narrator’s life laid out before him; the last story, shorter, is about endings. In between is a cycle of stories that seem to age the way we do, each in our own manner, moving with the irregular phases of lives lived with faults, with pain, with regret, with mistakes.This gives a poem-like structure to the collection as a whole; it’s also one story, the story of a single metaphorical life cycle, not only of one person, but of a collection of people who are, in some ways, similar to each other. Or to us, the readers of the stories. There’s a recurring character, a Dr. Wall who does something important: he listens, his welcoming ear a balm for clients in need of help, desperate for answers though he has few to give. In Coburn, we make our way through our lives more or less on our own. We can look for help from somewhere else, and while it may be soothing to look, we don’t necessarily find it.There’s poetry in the individual stories themselves. In “Ginger,” a lost and talented writer leaves a trail of wrong men behind before she finds real love with perhaps the most damaged man she knows, the editor at the magazine where she works. And she knows she has to leave.

Standing on the Cambridge side of the Charles River, against a chill fall wind that sounded like a holler for help and would’ve bowled her over had she not clutched the rail, she began composing her last piece for Boston World. The first line struck a mood. November is a bone begging for a dog.

There—an exact, precise description of the exact, precise moment that Ginger, ambitious and intelligent, re-launches her search for happiness. She may not find it easily. But then, most of us don’t.Later stories show other character looking for their second acts, as Ellen Burnside does when she and her husband come into some money and need help to make it grow. Jack O’Grady is there, but he has his own lecherous motives. Coburn gives us pain to balance the pleasure, conflict to offset opportunity.Life does not glide smoothly for these characters in Coburn’s stories. Some of his people appear similar but show different facets of pain and struggle as they chase their own elusive state of human happiness. Perhaps it can be achieved. Perhaps not. Some of us give up.These stories that Coburn gives us are beautiful, lyrical portraits of a composite life, and there is something of an ambivalence to the collection as a whole, start to finish, that mirrors those same condition in real life.These stories show us what it is to be human in Coburn’s world. Never all the way happy, never all the way miserable, but striving to use our gifts toward an elusive something, salmon swimming against the current, driven to spawn. Most remarkably, though, is the beauty in which the stories are told.November is a bone begging for a dog?Of course it is. In Andrew Coburn’s world, it has to be.

Published on July 10, 2014 13:38

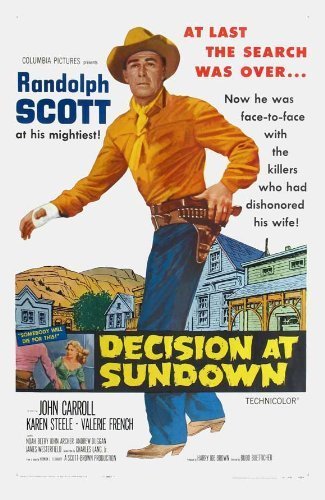

Femme Fatales Decision At Sundown

Ah, yes, femme fatales. Not only are they fine to gaze upon they are also a crime writer's best friend. Make a list of your favorite hardboiled and noir movies and you likely find a fatale femme in many if not most of them.

I mentioned "gazing upon"them. Well, in a unique twist there's a 1957 movie in which the femme sets a small town ablaze and nobody has even seen her for a long, long time.

The movie is "Decision at Sundown" and it's one of the justly famous Randolph Scott westerns directed by Budd Boetticher. The hallmarks of these pictures were the low budgets, the excellent scripts and the inability to sometimes tell the bad guys from the good.

Here we have Scott returning to ruin the wedding of the powerful man Scott believes stole his wife before she disappeared. Scott was in the war and when he returned he found she'd run off with the man who was about to be married.

Scott has reasoned in his loneliness, rage and misery that his wife was so ashamed of what she'd done that she couldn't face the judgment of the townspeople let alone that of her husband.

Scott plans to spoil the man's wedding by killing him, pushing him into a gunfight. The Sheriff tries to run him out of town but Scott and an old friend hole up, Scott waiting for the right moment.

What could have been a standard cowboy story becomes a fascinating drama as Scott gradually learns that the "innocent" wife he so loves had always cheated on him. The powerful man was only one of many.

We are near the end of the second act before Scott learns that his grief and madness--and Scott does a good job of portraying both--has been for a woman he knew nothing about.

A true femme fatale.

Published on July 10, 2014 08:00

July 9, 2014

LUST QUEEN/LUST VICTIM Robert Silverberg

LUST QUEEN/LUST VICTIM Robert Silverberg

Ed here: Robert Silverberg has had one of the most extraordinary careers

I've ever heard of. He was writing better at eighteen than many were at

thirty-six. Pulp, yes, but rendered with such facility that you had to

stand in awe of his talent and his ability to produce at Simenon-like

speed. He would go on to be one of science fiction's most important

writers and not just of his time but of all time.

I've been reading his work since I was twelve years old and rereading

a good deal of it from those venerable old Ace Doubles to the

brilliance of Dying Inside and The Book of Skulls to the more

recent Majipoor Chronicles.

I also read a number of his soft core novels. As he says below

they were good stories with the sex very tame. He could write

just about anything and do it well. I reread these two novels with

pleasure and nostalgia. They are not only excellent stories

they're also a chronicle of their times.

Robert Silverberg:

The Hamling operation published Lust Queen late in 1961 as Midnight Reader 401, the initial title in that series. Lust Victim followed in mid-1962 as Midnight Reader 429. It came out under the dumb title of No Lust Tonight, but for this reissue—the first time the book has been reprinted since its initial appearance—I have restored my original title.I felt absolutely unabashed about what I was doing. Writing was my job, and I was working hard and telling crisp, exciting stories. What difference did it make, really, that they were stories about people caught in tense sexual situations instead of people exploring the slime-pits of Aldebaran IX? I experienced the joy—and there is one, believe me—of working hard and steadily, long hours sitting at a typing table under the summer sun, creating scenes of erotic tension as fast as my fingers could move. Of course, what I was writing was not “respectable,” not even slightly, and so when people asked me what I did for a living I told them I was a science-fiction writer. (I was still writing some of that, too, as a sideline.) I could hardly tell my neighbors in my elegant suburban community that I was a professional pornographer.But was what I was writing really pornography?Not if your definition of pornography involves the use of “obscene” words or graphic physiological description. . .the stuff was really laughably chaste and demure. Everything was done by euphemism and metaphor. No explicit anatomical descriptions were allowed, no naughty words. About as far as you could go was a phrase like “they were lying together, and he felt the urgent thrust of her body against him, and his aroused maleness was penetrating her, and he felt the warm soft moist clasping and the tightening….”I limited myself to words that were in the standard dictionary because I had been warned at the outset that the publisher would not tolerate what he termed “vulgarisms.” One reason for this was that he genuinely didn’t like them—he was basically a very earnest and straight type of guy, who would much rather have been publishing science fiction—but he also knew that he might very well go to jail if he started printing them. Jail, yes—no matter what the First Amendment might say. (And eventually he did, many years later—not for publishing sexy novels, but for violating the postal code by sending an advertisement for an illustrated history of erotic art and literature through the mails!)The list of what was a “vulgarism,” though, kept changing in line with various court actions and rulings affecting Nightstand’s competitors in the rapidly expanding erotic-book business. All across the nation, bluenosed civic authorities were trying to stamp out this new plague of smut. Whenever a liberal-minded judge threw out a censor’s case, the word came down to us that we could take a few more risks in what we wrote, although our prose remained exceedingly pure by later publishing standards. But whenever some unfortunate publisher was hit by a fine, the word was passed to the little crew of Nightstand regulars that we had to try to be more proper.But I have no regrets about those five years in the sex-book factory—none. I don’t think any of us who wrote Nightstands do. It isn’t just that I earned enough by writing them to pay for that big house and my trips to Europe. I developed and honed important professional skills, too, while I was pounding out all those books.Writing those books was a terrific experience and I look back fondly on it without shame, without apologies.--from Robert Silverberg’s introduction to Lust Queen/Lust Victim by “Don Elliott”

Published on July 09, 2014 13:53

July 8, 2014

STRANGERS by Bill Pronzini

I typed this to myself after finishing STRANGERS. "I'd put this in the top five of the Nameless novels. For me it is the one most like Pronzini's masterpieceBLUE LONESOME. That poetic bleakness and despair. Mineral Springs isn't a town, it's a prison camp. And the characters are some of hisstrongest ever. And most subtle. A major, masterful work." This is a mordant trip into the past for Nameless. Cheryl Rosmond was Nameless' lover twenty years ago--one of the most serious loves of his life--but then constrained by moral duty he revealed to Police that her brother Doug was a murderer. Doug killed himself. Cheryl never forgave Nameless and left him. But now Cheryl's last name is Hatcher and her son Cody is suspected of being the rapist of three women in Mineral Springs, Nevada. With both the Sheriff and the townspeople convinced that Cody, who is anything but a saint, Cheryl pleads with Nameless to come help her.

Pronzini is the master chronicler of San Francisco but he's equally adept in bringing small towns to dark and secretive life as well. His people drive the story. From the Sheriff who has no doubts about his own judgment; to the ignorant but cunning man (one of Pronzini's finest creations) to what to marry Cheryl; to numerous former friends of Cody's who betray him without compunction; to Cheryl herself who proves to be a very different woman from the one Nameless imagined...this is a bitter and desperate trip into the darkest regions of classic noir.

Quoting myself: A major masterful work.

Published on July 08, 2014 15:07

July 7, 2014

Welcome to Carol Gorman's new and very cool website

Carol has asked me to answer a few questions. Carol's website www.carolgorman.com

I'm writing from my own experience. I wrote speeches and worked on campaigns for a Governor and two Congresspeople. I went on the road with them and produced TV commercials. .

.

I try to produce fifteen hundred words a at least six days a week. . .

1) What am I working on?

2) How does my work differ from others of its genre?I'm writing a political thriller. A campaign manager who watches as his candidate is framed.

I'm writing from my own experience. I wrote speeches and worked on campaigns for a Governor and two Congresspeople. I went on the road with them and produced TV commercials. .

.

I'm a political junkie and I like thrillers. 4) How does your writing process work?3) Why do I write what I do?

I try to produce fifteen hundred words a at least six days a week. . .

http://www.ufowatchdog.com/kevin_randle.htm www.carolgorman.comMy friend Colonel Kevin Randle a decorated war hero who has written dozens of books in many genres including military and UFO. He'll be the next guest.

Published on July 07, 2014 18:51

The Brutalist: A Gil Brewer Retrospective by Chris Morgan The LA Review of Books

The Brutalist: A Gil Brewer Retrospective by Chris MorganAugust 4th, 2013

for the entire post go here:http://lareviewofbooks.org/essay/the-...

RESET-+

RESET-+GIL BREWER'S CAREER spanned from the early 1950s to the mid-1970s. In that time, he wrote 50 novels, 33 of which were under his own name, as well as numerous short stories. The last novel published in his lifetime (under his own name) was in 1970, followed by a few additional years of ghostwriting and other hack work. He died in 1983 at the age of 60 from complications of long-term alcoholism. All signs indicate that he did not die feeling very accomplished; in fact, he wrote as much in 1977: “I’m 54 and I haven’t even started. Drank too much and was always in a rush to make enough $ just to get by. Now I’d like to try my hand at writing well […] If I was well I might stand a chance.” In addition to struggling to publish as the 1970s came around, Brewer affirmed his belief that what he had published failed to meet his (or anyone’s) standards of respectable or memorable literature. It is the kind of self-flagellating assessment common among writers, but which carries a more profound sting for writers of genres in which respectability is neither guaranteed nor even the point in the first place.Brewer spent the majority of his career trafficking in verbal sleaze, or at least what passed for sleaze at that time. Indeed, his entire livelihood came from writing works in which lurid narratives were rendered in a punchy, unadorned prose style — works with titles like The Angry Dream,Appointment in Hell, The Vengeful Virgin, Nude on Thin Ice, The Brat, The Bitchand Backwoods Teaser. They made for reading that was pleasurable and easy to digest while entirely devoid of nutrients. But it was an easy livelihood to make. Gil Brewer wanted nothing more than to be a writer, and he came of age at a time when writing was actually very good business so long as it was of a certain kind. Destined to have an impact lasting no longer than a morning commute, cheaply produced mass market paperback books took up a great deal of space in newsstands in the mid-20th century. Such a system was easy money for all involved and especially helpful in facilitating a burgeoning artistic career, as for William S. Burroughs, Harlan Ellison, and Ed Wood. For others, though, it became something of a niche from which it was very hard to escape. Brewer thought himself in the former category — an author who would somehow jump to “serious” literature — but with each book he finished, he seemed ever cursed to live the literary life of crime, knowing full well that the likelihood of his works going out of print in his lifetime was almost certain. Unfortunately, he did not live to see his works brought back into print and his name put back into the marketplace in a far more prominent position than he was ever able to attain on his own.

Published on July 07, 2014 14:46

July 6, 2014

DAVE ZELTSERMAN For a Limited Time: Two Novels on Kindle for Under a Buck

For a Limited Time: Two Novels on Kindle for Under a Buck

Ed gere: Thanks to Bill Crider for the link.

Amazon.com: The Shannon Novels eBook: Dave Zeltserman: Kindle Store: From Shamus Award-winning author Dave Zeltserman comes these two gripping and intense thrillers unlike any you've ever seen. In BAD THOUGHTS horrifying murders are being committed in Massachusetts and everything seems to be pointing to one of two possibilities: Bill Shannon has gone insane or a killer has come back from the grave to torment him. In the sequel, BAD KARMA, Shannon has moved to Boulder, Colorado, and when he's hired to investigate the murder of two college students, he finds himself mixed up with deadly Russian gangsters, evil yoga studios, deviant cults, and worse!

Published on July 06, 2014 18:07

Frederic Brown

Frederic BrownYes, I had an epiphany last night. Honest. (It didn't cost much, either.) I was re-reading one of my favorite Fredric Brown novels, The Deep End, and I realized suddenly why I've always felt such a spiritual closeness to his crime fiction.

I had a paper route when I was twelve and thirteen. I delivered in the neighborhood where I lived, a working class quadrant of the small city packed with bars. The men and women in the bars always liked to treat to me a bottle of pop or a game of shuffleboard or pool. We were all Micks from the same parish.

I can't say I got to know any but a few of them personally. But I did have an understanding of them as an aggregate, especially the men who were in their twenties, their fates already sealed by families, lack of college education and, in most cases, a compliance with the wishes of the gods (Lovecraft's gods to my mind). And of course the women whose fates were sealed but even more by virtue of their gender.

The bar was their escape. My favorite bar was part of a seedy hotel. The owner liked hillbilly music and he put all of Elvis' Sun records on it as early as 1955 before Elvis was widely known. Same with Johnny Cash. A very cool place.

I overheard stories. Men fighting with their wives; men stepping out on their wives; men who couldn't pay their bills and were heavy into loan companies already. Some of the men blue collar, some of men lower-echelon white collar. There were fights sometimes; wives occasionally appeared and hauled their humiliated husbands out of the places. The great tragedy was the much-decorated Marine who'd fought in Korea. Popular high school basketball player, happy hard-working good looking guy who was crazy about his wife and brought her in frequently, lovely frail Irish girl-woman. He got killed in a highway accident and his wife (true facts) set herself on fire in grief.

Lives significant only to them and their kind (my kind).

And while I was reading The Deep End last night (a novel so redolent of Fifties morality it could be used in a sociology text book, even though it takes enormous liberties with the sexual mores of the time, the love affair here a knockout) I realized that I like Brown so much (I was already reading him back then) because he wrote about my neighborhood and my people. Most of his crime novels, I know now, are filled with the men and women in the bars on my old paper route.

I keep hearing about how Brown's Coming Back. I sure hope that's true.

Published on July 06, 2014 14:16

July 5, 2014

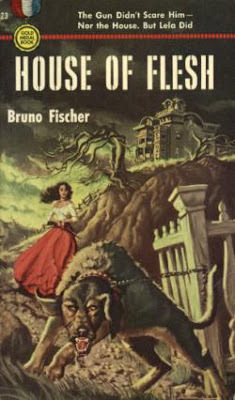

Forgotten Books: Bruno Fischer 2fer-House of Flesh & The Evil Days

Forgotten Books: Bruno Fischer 2fer-House of Flesh & The Evil Days

One way you can tell you're getting old is when the good girl in the Gold Medal novel appeals to you more than the femme fatale.

Somebody wrote me about a review I'd written a few years ago of Bruno Fischer's House of Flesh. In my review I was agreeing with science fiction writer Dave Bischoff's contention that the book is a mystery that combines gothic elements with some really horrorific moments. It's one of Fischer's best novels, a very sleek, dark whodunit that lags only at the very end because he runs out of suspects. There is a particularly nasty scene wherein dogs set upon the remains of a dead horse, the carcass having rotted before they got to it. The word "flesh" has multiple meanings in the novel. And nasty is the operative word for long sections of the book.

Before responding to the letter I decided to look through the book again. Held up very well. But as I read it I realized that Fischer had made the good girl so appealing--smart, funny, winsome, clean cut--that the protagonist seems sort of dotty to obsess over a rather odd woman whom he finds unattractive (but inexplicably sexy of course), aggravatingly mysterious and frequently irritable.

I know, I know--this is noir land where gonadic response to fate is not only standard but mandatory, thanks to the Law of The Crotch as writ large and eternal by James M. Cain.

The only way I can explain this misjudgement is my age. But an evening with the sweet, amusing good girl promises so much more fun than a few hours in the clutches of The Dragon Lady...

By the time they plant me Ill probably be reading those old-fashioned Harlequin romances. The clean ones.

-----

The Evil Days by Bruno Fischer

Bruno Fischer had one of those careers you can't have any more. There's no market for any of it. He started out as editor and writer for a Socialist newspaper, shifted to terror pulps when the newspaper started failing, became a successful and respected hardcover mystery novelist in the Forties and early Fifties, and finally turned to Gold Medal originals when the pb boom began. His GMs sold in the millions. His House of Flesh is for me in the top ten of all GMs.

Then for reasons only God and Gary Lovisi understand, Fischer gave up writing and became an editor for Colliers books. But he had one more book in him and it turned out to be the finest of his long career.

Fischer shared with Howard Fast (Fast when he was writing mysteries under his pen names) a grim interest in the way unfulfilling jobs grind us down, leave us soulless. Maybe this was a reflection of his years on the Socialist newspaper. The soullessness features prominently in The Evil Days because it is narrated by a suburban husband who trains to work each day to labor as an editor in a publishing company where he is considered expendable. Worse, his wife constantly reminds him (and not unfairly) that they don't have enough money to pay their bills or find any of the pleasures they knew in the early years of their marriage. Fischer makes you feel the husband's helplessness and the wife's anger and despair.

The A plot concerns the wife finding jewels and refusing to turn them in. A familiar trope, yes, but Fischer makes it work because of the anger and dismay the husband feels when he sees how his wife has turned into a thief. But ultimately he goes along with her. Just when you think you can scope out the rest of the story yourself, Fischer goes all Guy de Maupassant on us. Is the wife having an affair? Did she murder her lover? Is any of this connected to the jewels? What the hell is really going on here?

Sometimes we forget how well the traditional mystery can deal with the social problems of an era and the real lives of real people. The hopelessness and despair of these characters was right for their time of the inflation-dazed Seventies. But it's just as compelling now as it was then when you look at the unemployment numbers and the calm reassurances by those who claim to know that the worst is yet to come.

A wily little novel that rattled me the first time I read it and rattles me still on rereading.

POSTED BY ED GORMAN AT 9:51 AM NO COMMENTS: LINKS TO THIS POST

Published on July 05, 2014 13:06

July 4, 2014

William Marling on James M. Cain: Hard-Boiled Mythmaker

FROM THE LOS ANGELES REVIW OF BOOKS

for the entire article go here

https://lareviewofbooks.org/review/pu...

William Marling on James M. Cain: Hard-Boiled MythmakerPure CainSeptember 21st, 2011RESET-+HOW CAN YOU NOT like Mildred Pierce?

Whether it's Kate Winslet or Joan Crawford or James M. Cain's original, Mildred models an appealing blend of economic ambition, motherhood, and romance betrayed. With a new version of Mildred Pierce airing recently on HBO, reassessments are in order, not least because Cain himself was so attuned to economic hard times like our own.

David Madden championed Cain long before it was fashionable. I have in hand my 1968 copy of his Tough Guy Writers of the Thirties, which is dedicated "To James M. Cain, twenty-minute egg of the hard-boiled writers." This collection of criticism is still important, and in Madden's introduction he boldly set up Cain as a perspective on the hard-boiled world of Hemingway, Chandler, Hammett, Bellow, and McCoy. That viewpoint made the constellation of literature taught on campus look quite different, even in 1968. Although the multi-talented Madden was principally a fiction writer (his fourth novel, The Suicide's Wife, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize) and director of the creative writing program at LSU, in his free moments he continued to champion Cain. He wrote James M. Cain (1970) and Cain's Craft (1985), and organized the first ever James M. Cain Conference, held at the unlikely venue of Baylor University amid the arcana of the Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Collection. I was there, and believe me, listening to Madden begin his paper by evoking an imaginary theater marquee and intoning "JAMES ... M ... CAIN" was, for some years, my definition of academic cognitive dissonance.

Cain is mainstream now, but no less shocking. Students come to him chiefly in creative writing courses, where instructors cast his gems before students as models of clean prose: "'They threw me off the hay truck about noon' — see if you can combine setting, character, and conflict like that." But not so many aspiring creative writers read all of The Postman Always Rings Twice, much less the rest of Cain's oeuvre. It is now legit to teach Cain in American literature courses, if you ignore arched feminist eyebrows, but students are often genuinely shocked. How can he imply such nasty things about love, lawyers, the state, and human nature?

Roy Hoopes' monumental Cain: The Biography of James M. Cain (1982) helped to answer those questions. It seems that Cain was living libidinally in the 1920s and finding his style between the wit of Dorothy Parker and the sarcasm of H. L. Mencken, while reporting from West Virginia coal fields and New Jersey docks. In March of this year Hilton Als returned to the biographic in the New Yorker, linking Cain's more positive representation of women in Mildred Pierce to his "befriending" Kate Cummings (Cain often befriended women other than his current wife). But no writer transcends his period simply by befriending the right people. I myself placed Cain in a socioeconomic context in The American Roman Noir (1995). What he has to say on that score still resonates. It is now clear that Cain was among the most adept economic fabulists of his epoch, a talent he honed at the Baltimore American beginning in 1917. In The Embezzler (1940), he even named the archetypal crime of the Depression, a judgment later confirmed by John Kenneth Galbraith.

for the entire article go here

https://lareviewofbooks.org/review/pu...

William Marling on James M. Cain: Hard-Boiled MythmakerPure CainSeptember 21st, 2011RESET-+HOW CAN YOU NOT like Mildred Pierce?

Whether it's Kate Winslet or Joan Crawford or James M. Cain's original, Mildred models an appealing blend of economic ambition, motherhood, and romance betrayed. With a new version of Mildred Pierce airing recently on HBO, reassessments are in order, not least because Cain himself was so attuned to economic hard times like our own.

David Madden championed Cain long before it was fashionable. I have in hand my 1968 copy of his Tough Guy Writers of the Thirties, which is dedicated "To James M. Cain, twenty-minute egg of the hard-boiled writers." This collection of criticism is still important, and in Madden's introduction he boldly set up Cain as a perspective on the hard-boiled world of Hemingway, Chandler, Hammett, Bellow, and McCoy. That viewpoint made the constellation of literature taught on campus look quite different, even in 1968. Although the multi-talented Madden was principally a fiction writer (his fourth novel, The Suicide's Wife, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize) and director of the creative writing program at LSU, in his free moments he continued to champion Cain. He wrote James M. Cain (1970) and Cain's Craft (1985), and organized the first ever James M. Cain Conference, held at the unlikely venue of Baylor University amid the arcana of the Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Collection. I was there, and believe me, listening to Madden begin his paper by evoking an imaginary theater marquee and intoning "JAMES ... M ... CAIN" was, for some years, my definition of academic cognitive dissonance.

Cain is mainstream now, but no less shocking. Students come to him chiefly in creative writing courses, where instructors cast his gems before students as models of clean prose: "'They threw me off the hay truck about noon' — see if you can combine setting, character, and conflict like that." But not so many aspiring creative writers read all of The Postman Always Rings Twice, much less the rest of Cain's oeuvre. It is now legit to teach Cain in American literature courses, if you ignore arched feminist eyebrows, but students are often genuinely shocked. How can he imply such nasty things about love, lawyers, the state, and human nature?

Roy Hoopes' monumental Cain: The Biography of James M. Cain (1982) helped to answer those questions. It seems that Cain was living libidinally in the 1920s and finding his style between the wit of Dorothy Parker and the sarcasm of H. L. Mencken, while reporting from West Virginia coal fields and New Jersey docks. In March of this year Hilton Als returned to the biographic in the New Yorker, linking Cain's more positive representation of women in Mildred Pierce to his "befriending" Kate Cummings (Cain often befriended women other than his current wife). But no writer transcends his period simply by befriending the right people. I myself placed Cain in a socioeconomic context in The American Roman Noir (1995). What he has to say on that score still resonates. It is now clear that Cain was among the most adept economic fabulists of his epoch, a talent he honed at the Baltimore American beginning in 1917. In The Embezzler (1940), he even named the archetypal crime of the Depression, a judgment later confirmed by John Kenneth Galbraith.

Published on July 04, 2014 11:17

Ed Gorman's Blog

- Ed Gorman's profile

- 118 followers

Ed Gorman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.