Ed Gorman's Blog, page 82

July 25, 2014

TARZAN VS. FRANKENSTEIN ON THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU

TARZAN VS. FRANKENSTEIN ON THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU by Fred Blosser If you’re a pulp fan, you’d buy a novel called “Tarzan vs. Frankenstein on the Island of Dr. Moreau” in a heartbeat, wouldn’t you? If you’re not necessarily a pulp fan, you’re surely curious about the mash-up, at least. If you’re an Edgar Rice Burroughs enthusiast, you probably know where this is going.

One of seven magazine novels produced by Burroughs in a white-hot creative frenzy in 1913, “A Man without a Soul” is better known to later readers under its hardcover and paperback title, “The Monster Men.” “Man, monster, or jungle god?” asks the blurb inside the 1963 Ace Books softcover. This edition, cover art by Frazetta, cover price of 40 cents, was one of the torrent of Burroughs reprints that poured out of Ace, Ballantine, Canaveral Press, and Dover during the upswing of the ERB revival 50 years ago.

Dr. Arthur Maxon, a visionary scientist (Burroughs calls him a biologist, today he’d be termed a biochemist, I imagine), has discovered but not perfected the science of creating artificial human life in chemical vats. Initially deciding to abandon his studies and seek rest after a grueling series of false starts, he books an ocean voyage with his virginal twenty-ish daughter Virginia. Then his mania returns and he alights on a jungle island off Borneo. There, setting up a laboratory and enlisting a new assistant, Von Horn, who has designs on Virginia, he resumes his experiments.

Frustratingly, he finds little more success than he achieved in the States. He manufactures twelve specimens in crudely human form, physically powerful but misshapen and mentally deficient. He keeps them hidden from Virginia, and Von Horn keeps them under control with a bullwhip, just as Dr. Moreau kept his own unholy creations in line in the H.G. Wells novel. Undeterred by the new disappointments, Maxon prepares to formulate Number Thirteen. Next day, he and Von Horn find the chemical vat shattered, and a stranger turns up, a muscular, handsome young man in appearance, but inarticulate: who or what else could he be but Number Thirteen?

Von Horn decides to kidnap Virginia with the help of Malay henchmen who, in turn, plan to double cross him and sell her to a Malayan pirate chief, Muda Saffir. To the rescue, plunging into a waiting gauntlet of pirates, headhunters, and orangutans, leading his crew of grotesque predecessors -- Number Thirteen, renamed Bulan by the awestruck headhunters “in view of his wonderful fighting ability.”

As even this brief summary suggests, the tale is constructed on a series of plot devices (I suppose hard-hearted critics would say “contrivances”) that Burroughs later used time and again in his fiction. There’s the stalwart, nearly naked jungle hero; the brilliant but naive father, the devoted but spunky daughter, and their duplicitous associate with a shady past (the kind of character Arthur Kennedy played so convincingly in the movies); somebody with amnesia; a case of mistaken identity; an Edwardian-era class line (in this case, a more troublesome demarcation seemingly between human and non-human) that separates two lovers who obviously are meant for each other; and a rumored treasure that also incites the bad guys. You can play endless rounds of Mad Libs by leaving the names blank and filling in with those from almost any later Tarzan novel.

Of course, in 1913, when only the first two Tarzan novels had been published, and the first Tarzan movie was still five years away, these elements would have been a little fresher for ERB’s pulp magazine audience, and if you love Burroughs as many of us do, who cares anyway? This seemed to be a time of experimentation for ERB, much like Dr. Maxon’s own trial-and-error, when he realized that he had a hit with Tarzan and appeared to be investigating whether he could jumpstart other jungle heroes with equal success. “The Cave Girl,” also set in the South China Sea, whose hero is called Thandar, was another product from 1913. Maybe he decided he had greater potential for a series with Tarzan, or maybe having taken Bulan and Thandar to a natural stopping point, there wasn’t any farther to go with them.

I was one of those who read the Ace paperback as a kid, and after some 50 years, I vividly remembered the scene where Bulan and the Monster Men swarm onto a canoe crammed with headhunters:

“For several minutes that long, hollowed log was a veritable floating hell of savage, screaming men locked in deadly battle. The sharp parangs of the head hunters were no match for the superhuman muscles of the creatures that battered them about; now lifting one high above his fellows and using the body as a club to beat down those nearby; again snapping an arm or leg as one might break a pipe stem; or hurling a living antagonist headlong above the heads of his fellows to the dark waters of the river. And above them all in the thickest of the fight, towering even above his own giants, rose the mighty figure of the terrible white man, whose very presence wrought havoc with the valor of the brown warriors.”

Holy cow, it doesn’t get much better than that. No wonder it made such an impression on me as a 12-year-old. This is the same immediacy, violence, and sensory immersion that today’s moviemakers achieve with the help of modern CGI and kinetic editing -- and it’s in a pulp novel written a hundred years ago. You might snidely fault Burroughs for describing his hero as a “white man,” but surveying modern action movies, where the hero might be played by Denzel Washington or Idris Elba, but the villains are more likely than not to be Middle Eastern, Hispanic, Asian, or Slavic, can we say that popular entertainment is much more enlightened in 2014? Only a little more subtle about pandering to xenophobia.

It was instructive to go back recently and re-read the book with an adult perspective. It’s apparent that ERB was still honing his craft in his second hectic year as a professional writer. The build-up through the first two chapters is rather slow -- not dull, but there isn’t much in the way of action as characters are introduced and conflicts are foreshadowed. The middle portion moves at a good pace as the chase begins and ERB employs his frequent structure of cutting back and forth between different groups of characters. He leaves one group at the mercy of a cliffhanger as he suddenly transitions to parallel action by another group. Then, putting the next set of characters in danger from a different threat, he goes back to resolve the earlier cliffhanger.

The final three chapters downshift gears again as Burroughs resolves -- mostly through dialogue and exposition -- the two main characters’ romantic dilemma: although Virginia falls in love with Bulan, can they establish a relationship when he’s not only uncivilized by conventional standards, he’s not even human? The problem may still seem surprisingly compelling for today’s readers of romantic fantasy fiction, who worry that the teenage human girl will never get together with the teenage vampire boy. But today’s reader is likely to expect that the resolution will be better paced. Burroughs himself improved his story construction as he gained more experience and practice, so that the beginning, middle, and end all had plenty of action. The tradeoff was that, even if his later novels technically are more proficient, they largely lack the energy that charges “The Monster Men.”

Some readers believe that Burroughs cheated with the resolution he devised, but for me, not a problem. He plants a clue early on, and unlike today’s romantic readers who don’t care whether Edward is a vampire or Jacob is a werewolf, Burroughs surely knew what his 1913 escapist audience would accept and what they wouldn’t.

One of the characters is an excitable Chinese cook, Sing Lee, who talks in patois. ("Him live. Gettem lilee flesh wounds. Las all.") He turns out to be brave, resourceful, and shrewder than the white guys realize. Even at face value, he isn’t much more outrageous a caricature than the comic relief characters written by Chinese scriptwriters and broadly played by Chinese actors in Jackie Chan’s and Stephen Chow’s Hong Kong action comedies today.

Like Frankenstein’s monster, Maxon’s creations pathetically realize that they are outcasts. Instead of being enraged about their situation, like the creation in Mary Shelley’s allegorical novel, they are resigned to it: “it would be better were we to keep forever from the sight of men.” Here ERB anticipates Boris Karloff’s and James Whale’s sympathetic treatment in “The Bride of Frankenstein” (1935), in which the creature moans, “We belong dead” after he is spurned by his intended mate. In a weirdly kinky scene, the Monster Men decide they’re better off finding sexual partners among female orangutans (“I see a beautiful one yonder now. I am going after her”), provoking a bloody fight with the male apes. Burroughs lifted ideas from other writers, but they were usually the greats (Twain, Swift, Verne, Anthony Hope), and he rarely did so without giving them his own thoughtful inflection.

Burroughs apparently liked the basic premise of artificial life and used it again 25 years later in the ninth book in the John Carter series, “Synthetic Men of Mars.” That novel doesn’t get a lot of love from ERB fans like Richard Lupoff, but I think it’s one of Burroughs’ more inspired efforts. Going “The Monster Men” one better, the dashing hero undergoes a brain transplant so that he can infiltrate an enemy city and save his sweetheart; he spends most of the novel in the body of a lumbering, Quasimodo-ugly synthetic man, and wonders whether he’ll ever get back into his own body.

There are reports of a new Tarzan movie in the works. I wish they’d tackle “The Monster Men” instead. I suppose the failure of “John Carter” makes it unlikely that Hollywood will ever try an untested Burroughs character again, but maybe they could call it “Tarzan vs. Frankenstein on the Island of Dr. Moreau.”

Published on July 25, 2014 20:16

The Winner in our Undiplomatic Murder Tor Giveaway

Pat Donnelly

245 West Bayberry Lane

Upper Darby PA 19082

Congratulations, Pat!

Please e mail me.

Published on July 25, 2014 16:17

From Ron Goulart-The Great John Easy Mysteries

Ed: In answer to your query as to my thoughts and innermost feelings about my four John Easy, Hollywood Dick, novels since he was resurrected last year from the 1970s to the world of eBooks and audio books. Having a new potential audience for the series is just dandy. But I do wish more readers would find the books in the vast electronic jungle. Critics and readers like yourself and others have championed Easy for years, but it would be nice if more readers kept discovering Easy. I think the best book to start with is THE SAME LIE TWICE, 3rd in the series. It's my favorite. About adultery, crooked SoCal goverment, a missing woman. smoggy weather and Hollywood fringe people.Check with me again next year for another report. Best, Ron Goulart

Published on July 25, 2014 10:21

July 24, 2014

Forgotten Books: The Dead Beat by Robert Bloch

I've always admired the novel that Robert Bloch wrote immediately following publication of Psycho. I am one of four people on the planet who can make that claim.

What I've always liked about it is the way Bloch took a sleazy no-good psychotic bastard and set him right down in the middle of a Midwestern family that could have doubled as sit-com people. Bloch really makes you care about these folks and how they are so slow to catch on to the psychotic jazz musician they make the mistake of trying to help.

The title signals the era, the early sixties when the Beats were so much in the news. Bloch shows us a kind of faux beat existence with the musicians we meet early on. Bloch gets the one night stand life (in both meanings of that phrase) down just as well as he gets the middle-class days and nights of the family the musician will ultimately turn on. For Bloch this is a return of sorts to his Fifties paperbacks such as The Will To Kill and The Kidnapper. Jim Thompson country before anybody knew who Thompson was. (Bloch bristled when I asked him once if Thompson had ever been an influence--he said he'd never heard of Thompson until much, much later.)

Reviewers of the time didn't like the relatvely slow pace. They also complained that the novel didn't offer the shock or sass of Psycho (I say sass because the novel is very funny in places--something Hitchcock picked up on immediately). I like the treachery and the darkness here. I didn't used to believe in evil. But now I do. Robert Bloch brings to life the kind of evil all around us.

Published on July 24, 2014 15:11

July 23, 2014

Pro-File: Ariel S. Winter

[image error]THE TWENTY-YEAR DEATH

Ariel S. Winter

August 2012

ISBN: 978-0-85768-581-0

Cover art by Chuck PyleRead A Sample Chapter

Order Now

1. Tell us about your current novel.

It's a bit of a stretch to call The Twenty-Year Death current since it came out in the summer of 2012, but it's just come out in a completely new format that I'm very excited about. The book as a whole tells of the twenty-year descent of the great American novelist Shem Rosenkrantz from bestselling literary darling to out-of-work Hollywood hack. The story is told through three separate mystery novels each in the style of the greatest crime writer of the decade in which that part of the story is set: Georges Simenon, Raymond Chandler, and Jim Thompson. It was important to me that each of the books operated independently from each other, as though each section was a lost novel of its respective era. That way if a reader read just one portion of the novel, he would feel as though he had read a complete novel, but if he read the whole thing as intended, it added up to a greater work. My original vision of the novel was as a boxed paperback set, and my editor Charles Ardai agreed. For cost reasons, however, and to make the biggest splash, we put it out as a single hardcover. This month all three books were released as independent mass market paperbacks. Now some readers might only experience a part of the story, or read the books in a different order than in the single-volume edition, and it will be interesting to hear how those experiences are different.

2. Can you give a sense of what you're working on now?

My next novel is a robot romance in the Bronte tradition. Set in a dystopic future in which humans are a small minority, it tells of an aged robot who rents a beach-side cabana to contemplate his future. He's been in a terrible accident, and the societal expectation is that he should deactivate himself, but he's not ready to die. While at the beach, he becomes obsessed with the robot family that lives in the big house that overlooks the beach from the top of the cliff. Through a series of interlocking narrators, he learns the terrible secrets that separate this family from robotkind.

3. What is the greatest pleasure of a writing career?

Now that I have a real published book out, there's some comfort that there's tangible evidence that I existed. If I die tomorrow, even if my book goes out of print, it still exists out there, to be found, worthy of a footnote at least.

4. What is the greatest DISpleasure?

The years and years of toiling with very little encouragement, and the shock that even after you publish a novel to critical acclaim and with good sales figures, it doesn't mean that anyone will rush to publish you again. The uncertainty with the years and years between paychecks.

5. If you have one piece of advice for the publishing world, what is it?

Don't forget the booksellers. The booksellers are who sell the books. Not only is it important to cultivate a relationship with as many booksellers as possible, but publishers should help to publicly champion booksellers, emphasizing the role they serve in the literary culture. If the general public began to feel that a bookseller should be consulted like a sommelier, it would help save bookstores, and it will ensure the understanding that there's a reason that 99% of books that should be read are published, not self-published.

6. Are there two or three forgotten mystery writers you'd like to see in print again?

I'm not knowledgeable enough to know of any forgotten mystery writers. NYRB, Hard Case, and other presses like them seem to be doing a great job of bring deserving authors back into print.

7. Tell us about selling your first novel. Most writers never forget that moment.

I was cooking dinner when my agent called. I don't remember what I was cooking, but I remember I was using a frying pan on the front right hand burner, and it was something time-sensitive, and there was a lot of noise in the kitchen, my daughter, my wife at the sink, so I was distracted. The months of trying to sell had worn me down, so that it was almost as though the news passed right by me that it had happened. There was a delay in the excitement for some reason. Of course, my wife would probably tell me that I have all of these details wrong. In any event, the moment is hyper-real for me, like the world shrunk into me at that moment. You're right that you don't forget it, but I'm not sure I remember it either. It was epochal.

Published on July 23, 2014 15:01

July 22, 2014

One of the great B movie series THE WHISTLER

COLUMBIA CRIME: THE WHISTLER

Posted by R. Emmet Sweeney on July 22, 2014 Movie Morlocks

Posted by R. Emmet Sweeney on July 22, 2014 Movie Morlocks

For the entire piece go here: http://moviemorlocks.com/2014/07/22/c...

“I am The Whistler. And I know many things for I walk by night. I know many strange tales hidden in the hearts of men and women who have stepped into the shadows. Yes, I know the nameless terrors of which they dare not speak!” -intro to each iteration of The WhistlerIn 1943 Harry Cohn was seeking a successor to Ellery Queen, Columbia’s detective series that cranked out ten features from 1935 – 1942. Noticing the popularity of the violent radio show, Cohn purchased the film rights to The Whistler in ’43, and bequeathed production duties to Rudolph C. Flothow, who had recently completed the Columbia adventure serial The Phantom. Much of that same team came along on The Whistler, including cinematographer James S. Brown, Jr. and art director George Van Marter. To retain the flavor of the radio program, the show’s creator J. Donald Wilson contributed the story (Ellery Queen veteran Eric Taylor wrote the script). Wilson’s creation was more dark and adult-themed than some of the other radio hits like The Shadow. One of his stories entitled Retribution “was a tale of revenge and murder involving an evil man who hacked up his wife and stepson in order to lay claim to their money.” That according to Dan Van Neste, who literally wrote the book on The Whistler film series.The first feature has Dix play a grieving husband who schedules his own date with death. Terminally depressed following the tragic passing of his wife, which may or may not be his fault, Dix puts out a hit on himself. He puts out the contract through an interlocutor at a dingy seaside dive called The Crow’s Nest. The payment is delivered by a deaf and dumb kid whose nose is forever buried in a Superman comic, foreshadowing the blindness of all the characters in this cruelly ironic tale. For one of the things The Whistler knows is that Dix’s wife is alive – and his attempts to call off his own murder put all of his family and friends in jeopardy. Especially when the hitman is a self-styled intellectual reading a book entitled, “Studies in Necrophobia”. He wants to use Dix as a test case for a new kind of murder – literally trying to scare him to death. The film was a sizable critical and commercial hit for a B-movie, garnering positive notices across the board, as the studio crows in this two page advertisement (click to enlarge):This guaranteed more work for everyone involved. The Power of the Whistler (1946) is a slow-burn thriller about an amnesiac who may or may not be a homicidal maniac. This entry, written by Aubrey Wisberg, exemplifies the storytelling ethos of the series, which is: give away as little information as possible. The idea was audiences would have to guess at whether Dix would end up hero or villain, alive or dead. The search for backstory becomes an active goal of the plot, instead of information dumped early on. So in The Power of the Whistler Dix and his latest twenty-something love interest criss-cross NYC (including a “bohemian” Greenwich Village cafe called The Salt Shaker) for clues to his identity. The film sustains this mystery for most of its running time, despite Dix’s penchant for leaving dead animals in his wake. Directed by the insanely prolific Lew Landers, The Power of the Whistler is littered with uncanny images. One is a reflection of a little girl in a taxicab mirror as she cradles her dead kitten, as Dix and his latest love interest move forward in their investigation of his past. Richard Dix is something of an ideal actor for these games, as at this point in his career there was something wounded and slow-moving about his performances. He had lost his matinee-idol looks as he entered his fifties (though The Whistler’s women beg to differ), a heaviness added to his face and his walk, giving him a blankness well suited to the series’ goal of motivational ambiguity.

Published on July 22, 2014 14:56

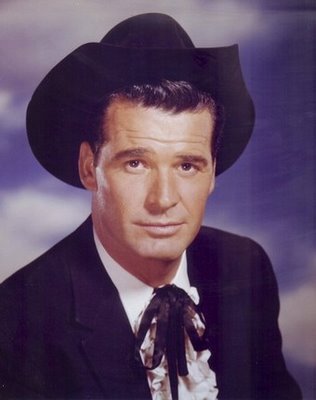

MAX ALLAN COLLINS ON THE PASSING OF JAMES GARNER

from http://www.maxallancollins.com/blog/

Like most writers who’ve had any sort of success – and this seems to apply particularly to mystery writers – I get questioned frequently about influences. If you’ve followed these updates or seen me on a convention panel or maybe just chatted with me, you know the list: Hammett, Cain, Chandler, Spillane, and a bunch of others. Writers all.

And I sometimes mention – as do such contemporaries of mine as Bob Randisi, Ed Gorman and Loren Estleman – the impact that series television had on me as a writer. Not every writer is secure enough to admit being influenced by what we used to call the boob tube (I always hear Edith Prickley saying that). But those of us who grew up in that wave of TV private eyes in late fifties were probably as influenced by such shows as Peter Gunn, 77 Sunset Strip, Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, Perry Mason and Johnny Staccato (among others) as we were Hammett, Chandler and Spillane.

More often (though still relatively seldom) you’ll hear a mystery writer admit to having been influenced by filmmakers. I frequently mention directors Alfred Hitchcock and Joseph H. Lewis, and such movies as Kiss Me Deadly andChinatown. Add Vertigo to those last two and I would challenge you to find many novels that stack up, even by the masters.

But it’s rare that any writers think to mention the influence actors have had on their fiction. I know that Italian western-era Lee Van Cleef influenced my Nolan series, for example, and Bogart is someone that writers sometimes aren’t embarrassed to cite as influential on their work. Not often, but it happens.

For me, the passing of James Garner – a man I never met and never had contact with – reminded me how big an influence this actor was on my life and my work. Before the TV private eye fad, there was the western craze, and discovering Maverick at a very young age shaped me in a way that rivals any parent or mentor. Now of course Roy Huggins had a lot to do with that, as the creator and frequent writer on the series, but it was Garner who brought life to the character, whose like we’d never seen.

Bret Maverick was a big, good-looking guy, able to handle himself with his fists and passably well with a gun (despite his claims at being slow on the draw). But he would rather charm or con his way out of a jam than fight or shoot. He was quick with a quip but never seemed smug. He was often put upon, and didn’t always win. Though he was clearly better-looking and more physically fit than your average mortal, he conveyed a mild dismay at the vagaries of human existence. And he did all of this – despite (or in addition to) Roy Huggins – because he was James Garner.

Garner’s comic touch was present in much of his work, and of course Bret Maverick and Jim Rockford were essentially the same character. And no matter what literary influences they may cite, my generation of private-eye writers and the next one, too, were as influenced by The Rockford Files as by Hammett, Chandler or Spillane. The off-kilter private eye writing of Huggins and Stephen Cannell made a perfect fit for Garner’s exasperated everyman approach, but it was just notes on a page without the actor’s musicianship.

Not that Garner couldn’t play it straight – he was, in my opinion, the screen’s best Wyatt Earp in Hour of the Gun, and as early asThe Children’s Hour and as late as The Notebook he did a fine job minus his humorous touch. But it’s Maverick and Rockford – and the scrounger in The Great Escape, the less-than-brave hero of Americanization of Emily, and his underrated Marlowe – that we will think of when Garner’s name is mentioned or his face appears like a friendly ghost in our popular culture.

Garner’s attempts to resurrect Maverick were never very successful – Young Maverick a disaster, Bret Maverick merely passable, though his participation in the Mel Gibson Maverick film was on target. I was fortunate to get to write the movie tie-in novel of that and – despite an atypically mediocre William Goldman script – had great fun paying tribute to my favorite childhood TV show and to the actor I so admired. (If you read my novel and pictured Gibson as Bret Maverick, you weren’t paying attention.)

Like all of us, Garner was a flawed guy, though I would say mildly flawed. Provoked, his easygoing ways flared into a temper and he even punched people out (not frequently) in a way Bret Maverick wouldn’t. He never quite came to terms with how important Roy Huggins had been to the creation of his persona, and essentially fired him off Rockford after one season. The lack of Huggins and/or Cannell on Bret Maverick was probably why it somehow didn’t feel like real Maverick.

Garner had great loyalty to his friends, however, and as a Depression-era blue collar guy who kind of stumbled into acting, he never lost a sense of his luck or seemed to get too big a head. He resented being taken advantage of and took on the Hollywood bigwigs over money numerous times, with no appreciable negative impact on his career. He was that good, and that popular.

When he gave a rare interview, Garner displayed intelligence but no particular wit, and it could be disconcerting to see that famed wry delivery wrapped around bland words. Yet no one could convey humor – from a script – with more wry ease than Jim Garner. Perhaps he was funny at home and on the golf course and so on. Or maybe he was just a great musician who couldn’t write a note of music to save his life.

It doesn’t matter. Not to me. He influenced my work – particularly Nate Heller – as much as any writer or any film director. He was a strong, handsome hero with a twist of humor and a mildly exasperated take on life’s absurdities. I can’t imagine navigating my way through those absurdities, either in life or on the page, without having encountered Bret Maverick at an impressionable age.

Watch something of his this week, would you? I recommend the Maverick episode “Shady Deal at Sunny Acres,” which happens to be the best single episode of series television of all time.

J. Kingston Pierce has a wonderful post on Garner at the Rap Sheet, with links to his definitive (and rare) two-part interview with Bret Maverick himself.

M.A.C.

Published on July 22, 2014 08:21

July 21, 2014

John Sayles on Anthony Mann's Border Incident

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oxJK2w...

I never quit pushing Anthony Mann do I?

Mystery File did a fine piece on this movie. I've seen it two or three times and now I want to see it again.

I never quit pushing Anthony Mann do I?

Mystery File did a fine piece on this movie. I've seen it two or three times and now I want to see it again.

Published on July 21, 2014 13:58

July 20, 2014

"THE BURGLARS" (1972) STARRING JEAN-PAUL BELMONDO, OMAR SHARIF AND DYAN CANNON

Celebrating Films of the 1960s & 1970s

"WE WANT OUR DVD!": "THE BURGLARS" (1972) STARRING JEAN-PAUL BELMONDO, OMAR SHARIF AND DYAN CANNON

BY FRED BLOSSER from Cinema Retro

A particular kind of film was popular in, and almost unique to, the 1970s. I would call them “A-minus” movies. Not quite “A” because they didn’t feature trendy mega-stars like Newman, Redford, McQueen, Eastwood, Streisand, or Beatty, but not quite “B” either. Typically, they were international packages that starred a mix of American actors who, although past the peak of their popularity, still retained some marquee appeal for older moviegoers, and European actors who would draw overseas audiences. They usually were built around B-movie crime, spy, and thriller stories, but bigger-budgeted and more sophisticated than the standard “B,” and filmed on European locations, not a studio backlot in Culver City.

Henri Verneuil’s “Le Casse” (1971),” released in the States by Columbia Pictures in 1972 as “The Burglars,” exemplifies the genre -- French director; on-location filming in Greece; score by Ennio Morricone; the names of Jean-Paul Belmondo, Omar Sharif, and Dyan Cannon above the title; an able supporting cast of Robert Hossein (“Les Uns et Les Autres”), Renato Salvatori (“Luna”), and Nicole Calfan (“Borsalino”); and a script by Verneuil and Vahé Katcha based on David Goodis’ 1953 paperback crime noir, “The Burglar.”

Verneuil had recently aced a big hit in Europe and a modest hit in the U.S. with “Le Clan des Siciliens” (1969), also known as “The Sicilian Clan.” “The Sicilian Clan” is relatively easy to find in a sharp print on home video and TV (there was a 2007 Region 2 DVD, a 2014 Region 2 Blu-ray, and periodic airings on Fox Movie Channel). Unfortunately for A-minus aficionados, “The Burglars” is more elusive in a really good, English-language video print.

Professional thief Azad (Belmondo) and his partners (Hossein, Salvatori, and Calfan) have cased a villa in Athens whose jet-setting owners are away on vacation. A safe in the house holds a million dollars in emeralds. The thieves break into the house, crack the safe, and make off with the jewels, but two glitches arise. First, a police detective, Zacharias (Sharif), spots the burglars’ car in front of the villa. Azad chats with the detective and spins a cover story of being a salesman with engine trouble. Zacharias leaves, but it seems like too easy an out for the thieves.

Next, the plan to flee Greece immediately on a merchant ship falls through. The gang arrives at the dock and finds the ship undergoing repairs: “Storm damage. It will be ready to sail in five days.” They stash the money, split up, and agree to wait out the delay. Zacharias reappears, playing cat-and-mouse with the burglars. He’s found the opportunity to cash out big. Offered a meager reward by the billionaire owner of the jewels and “10 percent of the value” by the insurance company, he decides he’ll do better by finding and keeping the emeralds himself. In the meantime, Azad meets and romances Lena, a vacationing centerfold model (Cannon), whose role in the story turns out to be more relevant than it first seems.

Goodis’ novel was filmed once before as “The Burglar” (1957), a modestly budgeted, black-and-white programmer with Dan Duryea, Jayne Mansfield, and Martha Vickers, directed by Paul Wendkos. The script by Goodis himself, the photography in gritty Philadelphia and Atlantic City, Duryea’s hangdog performance, and Mansfield’s surprisingly vulnerable acting faithfully captured the bleak spirit of the novel.

Retooling the story as a shinier A-minus, Verneuil made significant changes. Duryea’s character, Nat Harbin, runs ragged trying to keep his fractious gang together and protect his ward Gladden, the young female member of the team, whose father had been Harbin’s own mentor. Verneuil tailors the corresponding character Azad to Belmondo’s exuberant, athletic personality and changes the dynamic between Azad and Helene, Calfan’s character. Where Gladden is brooding and troubled, Helene seems to be well-adjusted if somewhat flighty. When Nat realizes that he loves Gladden, it comes too late to save their doomed relationship. Azad and Helene find a happier resolution. The opportunistic cop in the novel and earlier movie, Charley, has little interaction with Harbin, but Belmondo and Sharif share ample screen time and charm as the two equally wily antagonists. Their final showdown in a grain-storage warehouse brings to mind, of all classic movie references, the climactic scene in Carl Dreyer’s “Vampyr” (1932).

Updating the technical details of the story, Verneuil turns the safecracking into a lengthy scene in which Azad uses a high-tech, punch-card gizmo to visually scan the scan the safe’s inner workings and manufacture a key that will open it. Roger Greenspun’s June 15, 1972, review in “The New York Times” took a dim view of Verneuil’s meticulous, step-by-step depiction: “Such a machine might excite the envy of James Bond's armorer, or the delight of Rube Goldberg. But what it does for Henri Verneuil is to fill up a great deal of film time with a device rather than with an action.” In fact, Verneuil was simply paying homage to similar, documentarian scenes in John Huston’s “The Asphalt Jungle” (1949) and Jules Dassin’s “Rififi” (1955) -- incidentally, one of Robert Hossein’s early films -- and at the same time avoiding repetition by employing the kind of Space Age gadget that fascinated 007 fans in the early ‘70s.

Greenspun also objected to “an endless (and pointless) car chase,” but the chase, choreographed by Rémy Julienne, isn’t exactly pointless: it adds an overlay of menace to the second, verbally cordial meeting of Azad and Zacharias. Besides, in the era of “Bullitt” (1968) and “The French Connection” (1971), a car chase in a crime film was good box office, as Verneuil certainly knew. The chase isn’t shot and edited as electrically as the ones staged by Bill Hickman for Peter Yates and William Friedkin, but it’s easily as entertaining as Julienne’s stunts for the Bond films.

Ennio Morricone’s eclectic score includes a jazzy, Europop-inflected title tune; dreamy easy-listening background music in the hotel cafe where Azad and Lena meet cute; sultry music in a sex club where Morricone seems to be channeling Mancini and Bachrach; and airy, Manos Hatzidakis-style string music in a Greek restaurant where Azad and Zacharias meet. It’s an inventive score, but not as well known as some of Morricone’s others, perhaps because it borrows so freely (with an affectionate wink and a nod) from his contemporaries.

There are a couple of versions of “The Burglars” as the French-language “Le Casse” on YouTube, only one of them letterboxed, and neither with English subtitles. Web sources indicate that Sony released the German-language version of the film, “Der Coup,” for the German DVD market in 2011; some say it includes English subtitles, others say it doesn’t. There was a letterboxed Alfa Digital edition of “The Burglars” in 2007 for the collectors’ market, and a letterboxed print occasionally runs on Turner Classic Movies. Those are probably the best bets for an English-track, properly widescreen (2:35-1) print, although in both cases the colors are muddy, dulling the bright cinematography by Claude Renoir that I remember seeing on the big screen in 1972.

Belmondo, Sharif, and Cannon probably have little name recognition among younger viewers today, and a scene in which Azad slaps Lena around, activating a clapper that cuts the lights in Lena’s apartment and then turns them back on with each slap, would never be included in a modern film. On the other hand, the mixture of crime, car chase, and romance might pique the interest of today’s “Fast & Furious” fans. In fact, with some rewriting (and further separation from Goodis’ noir universe), it could easily be remade as a future installment in the franchise, with Belmondo’s Azad repositioned as Vin Diesel’s Dom Toretto, and Sharif’s Zacharias rewritten and softened as Dwayne Johnson’s Agent Luke Hobbs.

It’s heartening that Sony Pictures Home Entertainment has begun to move older Columbia genre releases from its vaults to DVD and cable TV, often in first-rate condition. For example, a pristine print of “Thunder on the Border” (1966) ran recently on GetTV, Sony’s cable outlet for the Columbia vault. As another example, “Hurricane Island” (1951) has aired on Turner Classic Movies in perfectly transferred or restored Supercinecolor. It would be nice to see Sony offer a comparably refurbished print of “The Burglars” on American Blu-ray. If nothing else, the movie’s 45th Anniversary is only a year and a half away.

Posted by Cinema Retro in DVD/Streaming Video Reviews & News on Saturday, July 19. 2014

Published on July 20, 2014 07:58

July 19, 2014

The Stacks: Mr. Bad Taste and Trouble Himself: Robert Mitchum

The Stacks: Mr. Bad Taste and Trouble Himself: Robert Mitchum

:Almost 6,000 wordsfor the entire article go here:http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles... The Daily Beast

“He drank too much and smoked too much. He granted too many interviews full of cynical observations about himself and his business. He made too many bad movies and hardly any of the kind that stir critics to rapture or that, taken together, look like a life achievement worthy of official reward.God, some of us are going to miss Robert Mitchum!”—Richard Schickel

And he’s still missed, 17 years after his death. No, you sure don’t see movie stars like Robert Mitchum anymore. But we can still appreciate the real thing. In 1983, Robert Ward hung out with the star of Out of the Past, The Night of the Hunter, Cape Fear, and The Friends of Eddie Coyle, and wrote the following profile, “Mr. Bad Taste and Trouble Himself: Robert Mitchum.” It originally appeared in the March 3, 1983 issue of Rolling Stone and is collected in Ward’s terrific anthology, Renegades. It appears here with the author’s permission. —Alex Belth

A big, crazy, sexy sixty-five-year-old little boy who can’t get used to the idea that he’s supposed to act like, like Ward Cleaver, you dig?

Robert Mitchum is walking down this Kafkaesque hallway, holding his arms straight out in front of him, crossed, as though they’ve been manacled by the CBS production assistant who trucks along in front of him. Mitchum staggers a bit. All he drinks nowadays is tequila—and milk, though not together—and he had his first shot at one thirty in the afternoon, and now it’s ten thirty at night and he’s been through five interviews and a fifth of Cuervo Gold Especial and is fast moving into that strange land between dreams and wakefulness.

Published on July 19, 2014 09:58

Ed Gorman's Blog

- Ed Gorman's profile

- 118 followers

Ed Gorman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.