Deborah J. Ross's Blog, page 37

July 8, 2021

It's StoryBundle Time!

Collaborators is one of the fantastic novels in the newest StoryBundle, available now. This curated collection is a great way to discover new authors.

What's a StoryBundle and how I can get this one? Read below!

The Starting Hurricanes Bundle - Curated by Athena Andreadis

"Unhappy is the land that needs a hero." —Bertolt Brecht, Life of Galileo

"This is the hour of the Shire-folk, when they arise from their quiet fields to shake the towers and counsels of the Great." —Elrond of Rivendell, The Fellowship of the Ring

The Starting Hurricanes StoryBundle offers eleven fascinating speculative works that explore the concept of great changes wrought by people who are not Chosen Ones nor have god-like powers. Science fiction and fantasy (henceforth SFF) rely too heavily on these two modes; as a result, "mundanes" are often belittled, too frequently shown bereft of agency, imagination, courage or any ethical/moral compass beyond narrow self-interest.

This goes hand-in-hand with the predilection of the genre for autocratic authority structures, too frequently headed by charismatic psychopaths who are given huge dollops of leeway, to say nothing of boasting "optimal" genes (which demonstrates most SFF authors' fundamental misunderstanding of genetics and evolution). Almost always ignored are the loyalty networks and the sense of collective investment that actually make cultures and societies function—but also malfunction, when manipulated by grifters or thugs.

As the astrogator of acclaimed small indie press Candlemark & Gleam, I've had the honor and pleasure of helping to create and release some of the best new works that show that "regular people" can show transformative vision and power, for good or ill. And now I get to share such thought-experiments and flights of informed fancy with you in this kaleidoscopic bundle which explores the premise that even fluttering of insect wings can start hurricanes.

The settings in this bundle range from several versions of a devastated Earth to a Mars where terraforming attempts failed; from humanity in complex interplanetary conflicts to disquieting alien biologies; from exiles in search of a home to underdogs suffocated from being evaluated by rigid labels. The subgenres include space opera, near-future dystopia, far futures with magic-like technology, first contacts, adaptations to planetfalls. Hovering over all these explorations is the specter of the inherent limitations (and hence immovable dilemmas) of our physiologies—and the blinkers of our assumptions, that are often more hard-wired than we'd like to think.

A question that has been at the forefront of humanity's individual and collective thoughts is "How do we live honest, honorable lives?" It shapes cultures, societies, ethics systems; it determines what to pursue in science and art. And it's not reserved to elites but one that each human being ponders, no matter what their circumstances. The works in this bundle ask this question from multiple directions and come up with fascinating SFnal takes on this universal query, while also presenting riveting alternative worlds.

So strap into your acceleration couch, go through the preflight check and start the countdown to the jump. The Starting Hurricanes bundle will take you on astonishing journeys. And keep frequencies open for more StoryBundles curated by Candlemark & Gleam!

– Athena Andreadis

* * *

For StoryBundle, you decide what price you want to pay. For $5 (or more, if you're feeling generous), you'll get the basic bundle of four books in any ebook format—WORLDWIDE.

Dreams of Earth by Bud Sparhawk

The Janus Legacy by Lisa von Biela

Jumpship Hope by Adria Laycraft

One’s Aspect to the Sun by Sherry D. Ramsey

If you pay at least the bonus price of just $15, you get all four of the regular books, plus seven more books! That's a total of 11!

Fault Lines by Kelly Jennings

The Wan by Bo Balder

River of Dust by Alexander Jablokov

Finders by Melissa Scott

Collaborators by Deborah J. Ross

White Wing by Shariann Lewitt and Susan Shwartz

Edge of Heaven by RB Kelly

This bundle is available only for a limited time via http://www.storybundle.com. It allows easy reading on computers, smartphones, and tablets as well as Kindle and other ereaders via file transfer, email, and other methods. You get multiple DRM-free formats (.epub, .mobi) for all books!

It's also super easy to give the gift of reading with StoryBundle, thanks to our gift cards – which allow you to send someone a code that they can redeem for any future StoryBundle bundle – and timed delivery, which allows you to control exactly when your recipient will get the gift of StoryBundle.

Why StoryBundle? Here are just a few benefits StoryBundle provides.

Get quality reads: We've chosen works from excellent authors to bundle together in one convenient package.

Pay what you want (minimum $5): You decide how much these fantastic books are worth. If you can only spare a little, that's fine! You'll still get access to a batch of exceptional titles.

Support authors who support DRM-free books: StoryBundle is a platform for authors to get exposure for their works, both for the titles featured in the bundle and for the rest of their catalog. Supporting authors who let you read their books on any device you want—restriction free—will show everyone there's nothing wrong with ditching DRM.

Give to worthy causes: Bundle buyers have a chance to donate a portion of their proceeds to Mighty Writers and Girls Write Now!

Receive extra books: If you beat the bonus price, you'll get the bonus books!

StoryBundle was created to give a platform for independent authors to showcase their work, and a source of quality titles for thirsty readers. StoryBundle works with authors to create bundles of ebooks that can be purchased by readers at their desired price. Before starting StoryBundle, Founder Jason Chen covered technology and software as an editor for Gizmodo.com and Lifehacker.com.

For more information, visit our website at storybundle.com, tweet us at @storybundle and like us on Facebook.

July 2, 2021

Two Book Reviews Demonstrate the Future is not What We Expect

The Apocalypse Seven, by Gene Doucette (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

My introduction to Gene Doucette’s witty style was his previous novel, The Spaceship Next Door, reviewed here. This newest adventure has all the charm, warmth, and thoughtfulness I’d come to expect.

One morning, a small and disparate group of people – college students, a hermit preacher, an astrophysicist, for example – wake up to find the world changed. Each seems to be utterly alone. Familiar buildings are more or less intact, but wildlife and vegetation has taken over the university town of Cambridge. There’s no electricity, and all the batteries are dead. The astrophysicist notices the stars are in subtly wrong positions. As the group makes contact with one another, gathering at the university, they support one another when they aren’t arguing, for each has a different understanding of what has happened. Touré, a twenty-ish Cambridge coder, calls it the whateverpocalypse. Just as they learn they are not the only humans alive and suspect around a century has elapsed while they were unconscious, they begin to suspect they are not the only intelligent species on the planet, but it’s anyone’s guess whether the ghosts or aliens or whatevertheyare mean the human survivors well or ill.

By far, the sneak star of the book is Norman, the coywolf (coyote-wolf hybrid) tamed by the blind character, Carol.

Tiny Time Machine, by John E Stith (Amazing Select from Amazing Stories)

Tiny Time Machine, by John E Stith (Amazing Select from Amazing Stories) I’ll read anything by John E. Stith, but somehow I missed this charming short novel. The description says it’s “for young adults,” but I disagree. While teens are going to love it, and it’s a novel featuring young characters, it’s so full of buoyancy and hope that adults will gobble it up, too. Meg describes herself as the daughter of an angry scientist dad, so angry that he in fact turns a smartphone into a time machine that not only peeks into a not-too-distant future but allows people to jump into it. Alas, it’s not a future anyone would want to live in. The planet is dying, and humanity along with it. The oceans have turned into a stiff jelly, reminiscent of ice-9 in Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle. Meg and her new friend Josh embark upon a quest to stop a billionaire technologist whose well-meaning attempts to clean up the ocean’s plastic garbage will lead to this bleak future. Soon they’re on the run from the police, as well.

One of the things I enjoy about Young Adult novels is how teens can have agency, not only in their own lives but in the world. Typically, parents are therefore absent or dead (in Meg’s case, both of them, her father recently so), and that frees the characters from supervision. In this story, not having a parent deprives Meg and Josh of the perspective and resources an adult ally could offer. They have internal challenges of growing up and learning to work together, deal with jealousy, and so forth, all within the limitations that minors face. This is while figuring out what happens in the future and how to stop it.

As a bonus, the book contains a piece of short fiction, “Redshift Runaway,” set in the same world as Redshift Rendezvous. When a sentient alien pet runs wild on a starship traveling a significant fraction of the speed of light, where the laws of ordinary physics no longer apply, chaos ensues, but also understanding. Nobody writes relativity-based science fiction better than Stith.

June 28, 2021

Deborah Reads from "The Fallen Man"

In magical Renaissance Italy, art not only captures reality but remakes it. Shadows gather within the duke’s palazzo, threats that only the gifted young artist Rodiana can visualize through her painting. Danger lurks even closer, as a lecherous noble guest is bent on taking Rodiana for himself. Her best defense against the attack and its aftermath lies in the power of her art to both reveal and conceal the truth.

"The Fallen Man," is based on the life of Renaissance fresco painter, Onorate Rodiana, who escaped an assault by a wealthy courtier to become a notorious bandit queen. It's available for pre-order now and goes live on July 1, 2021.

June 25, 2021

Short Book Reviews: The H. P. Lovecraft Elder Gods Stalk Modern London

Dead Lies Dreaming, by Charles Stross (Tordotcom)

The Elder Gods have cast their long, twisted shadow over contemporary London, the “New Management” has transformed government into a private megacorporation, and supernatural powers are popping up in people of all walks of life. One billionaire tycoon will stop at nothing to acquire the one true Necronomicon, a cursed grimoire right out of H. P. Lovecraft. When a group of psychic misfits stages a bank robbery, ex-cop Wendy Deere is put on the job as private security to track them down and soon finds herself drawn in to the hunt for the ghastly book. The plot goes from playful to horrific, from reality-bending and beyond in true Stross fashion. Although this world has much in common with The Laundry Files, and I kept waiting for our friends from those stories to show up and save the day, to my mind this is a parallel-Laundry-Files universe, just as fun and wildly inventive, and it works great as a stand-alone.

June 21, 2021

Guest Post: Economic Self-Reliance and Well-Being in American Women

Gender, Capitalism, and Labor: The Relationship Between Economic Self-Reliance and Well-Being in American Women

by Sarah Madeleine Wheeler

The proposition that “Throughout U.S history a woman’s capacity for economic self-reliance is the most important determinant of her well-being” is not unreasonable and is well-supported by evidence; however, it is incomplete and fails to extend into the critique of capitalism, power and class disenfranchisement that is necessary for a well-rounded understanding. In any capitalist system, the powerful will seek to deprive the disadvantaged of monetary resources, the better to retain and stratify their own class privilege, and to maintain a desperate class of workers willing to labor on starvation wages. While the American race-caste system, dating back to the 1681 statues made in reaction to Bacon’s Rebellion (How America Invented Race, 2020), was orchestrated with the suppression and control of minority labor forces in mind, the domination of the largest minority on Earth pre-dates the invasion of the continent and composes the oldest form of unpaid labor. That a woman’s economic self-reliance is primary and critical to her well-being is true insofar as any disadvantaged person’s economic fortunes is thusly important to their fate within the capitalist system; that is to say, women’s rights are human rights and human rights are labor rights.

The proposition that “Throughout U.S history a woman’s capacity for economic self-reliance is the most important determinant of her well-being” is not unreasonable and is well-supported by evidence; however, it is incomplete and fails to extend into the critique of capitalism, power and class disenfranchisement that is necessary for a well-rounded understanding. In any capitalist system, the powerful will seek to deprive the disadvantaged of monetary resources, the better to retain and stratify their own class privilege, and to maintain a desperate class of workers willing to labor on starvation wages. While the American race-caste system, dating back to the 1681 statues made in reaction to Bacon’s Rebellion (How America Invented Race, 2020), was orchestrated with the suppression and control of minority labor forces in mind, the domination of the largest minority on Earth pre-dates the invasion of the continent and composes the oldest form of unpaid labor. That a woman’s economic self-reliance is primary and critical to her well-being is true insofar as any disadvantaged person’s economic fortunes is thusly important to their fate within the capitalist system; that is to say, women’s rights are human rights and human rights are labor rights. Prior to and during the strict control of women’s capital via legal statute, women frequently were capital, a reflection of both their reproductive capacity and of the unpaid labor they were expected to perform. From approximately 1600 onwards, both colonialist and Indigenous women (and children) functioned as chattel and “valuable cultural commodities to be taken hostage and exchanged” for inanimate objects and other capital (Brooks, 1996). In the wake of Bacon’s Rebellion, women were key to controlling the labor force through racial categorization; miscegenation laws combined with “according to the condition of the mother” clauses (Hening, 1823) ensured that neither women of color nor their descendents would have access to either freedom or capital of their own. As systems of power and control began to emerge, those women whose labor was not controlled by systems of servitude and racial disenfranchisement were constrained by the laws of men which erased their separate legal identities after marriage and stripped from them most claims to capital and property, a system known as coveture. The twin American disenfranchisements, on the basis of sex and on the basis of race, had devastating consequences for women’s well-being. For instance, renowned poet Phillis Wheatley, the founder of multiple American literary traditions, died at 31 years of age in wretched poverty as she struggled alone to support an infant son by working as a scullery maid, on account of both her race and her sex (Wikipedia, 2021; Phillis Wheatley clip…, 2014). Even Rachel Wells, a White woman who lent the hefty sum of £300 from her own resources to fund the Revolutionary War and therefore should have been a valued patriot, could not get her bond returned on account of her sex and was reduced to sleeping on straw in her old age, begging piteously in misspelled letters to Congress for “a little [interest]” from her ‘borrowed’ funds (Living Through War & Revolution, 1786). Many younger women took advantage of the war to leave their gender behind and cross-dressed as soldiers, the better to pursue their own wellbeing (Deborah Sampson Cross-Dresses…, 2019). That it was better to be a man at war than a woman at any occupation casts a stark light upon women’s fortunes during this era.

However, in the wake of the Revolutionary War, “the mothers of the republic were tasked with instilling in their sons the qualities of virtue, piety, and patriotism necessary to the young country’s future,” for which education was essential (Ware, 2015). While, as Ware observes (2015), access to segregated education was “a long way” from equality, “it was an opening wedge.” Indeed, the mothers of suffrage, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady-Stanton, were both educated women, a condition predicated by relative affluence which afforded them the liberty to pursue their life’s work. Anthony, a teacher who never married, astutely remarked on the grim dichotomy facing her sex: “I do not want to give up my life of freedom to become a man’s housekeeper. If a girl marries poverty, she becomes a drudge. If she marries wealth, she becomes a doll, and I want none of either.” (One Woman, One Vote, 1995) Her determination to retain her economic independence was no doubt a significant factor behind her ability to remain a staunchly active figure in the Women’s Movement until her death: better able to protect her own economic health, dispossessed by neither a feckless husband nor his descendants, with the right to access and manage her own economic resources, she was not reduced to working as a drudge or to homelessness in her twilight years for lack of a man to “cover” her.

By this time, the “New Woman” had formerly-unthinkable access to the value of her own labor, a condition which paid dividends in self-determination and overall wellbeing for American women. By 1910 women were 20% of the workforce; while marriage was still the dominant social goal and most wages were “turned over to their mothers,” these working women still utilized their newfound economic clout to engage in commercialized entertainments and leisure (Ware, 2015). With the newfound economic value of their labor, women were also newly able to engage in protest for better working conditions, such as the strike led by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union staged just two years before the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Fire (Ware, 2015). However, these rights and advantages were at the leading edge of labor activism; in 1920 a meager 8% of women belonged to a union, with those women not working for a wage facing raising living costs, poverty, extraordinary overwork due to the lack of mechanized appliances, and disease (Ware, 2015). Desperate for agency and resources in the face of these trials, a not-insignificant percentage of women took advantage of farm co-ops or homesteading statutes. The women who remained in the cities were increasingly engaged in collective action for the betterment of labor conditions and gender equality alike: Alice Paul, a highly-educated Quaker from a wealthy liberal-minded family, coordinated a diverse coalition from all classes and races that agitated tirelessly for suffrage. Paul was convinced that social work and charity were impotent means to improve society and help women: only the vote could give women the power to safeguard their wellbeing and interests, and it was impossible to effectively agitate for the vote without some measure of economic agency to facilitate the struggle.

While winning the vote was centrally important to women’s ability to safeguard their welfare, suffrage did not nullify the central importance of economic self-sufficiency, although it did give women superior avenues by which to ensure it. This framework provided the grounds upon which multiple scions of modern feminism were able to uplift themselves in the face of severe childhood poverty, by virtue of their ability to earn and keep wages. In Coming of Age in Mississippi, Anne Moody chronicles the desperate poverty of her sharecropper childhood home, which she was able to escape by virtue of both an academic scholarship and the money she was able to earn on her own recognizance. Without the money she scraped together tutoring, dishwashing, waitressing and other such jobs, Moody would have not been able to either feed herself or pay her tuition. In contrast, Judge Sonia Sotomayor was also the recipient of financial aid, but she did not have to work her way through high school or college despite her immigrant family’s poverty; instead, it was her mother who worked tirelessly after the death of Sonia’s father to support them both and further their educations (Sotomayor, 2013). This financial agency enabled them to move to a safer neighborhood and provided the young Sonia with the investment of an Encyclopedia Britannica, among other investments, which contributed not only to the safety and security of their home life but also enabled Judge Sotomayor to make the most of her considerable intellect.

Issues of economic self-sufficiency continue to affect women, dictating the outcome of such welfare issues as child care, divorce, elder care, and access to reproductive health services. Without financial agency, the thousands of women who chose divorce through the ‘70s, in one of “the greatest political acts many of us committed” (Makers Pt. II, 2013), could not have opted for better lives. While divorce is often proposed to be a negative consequence of feminism, this accusation neglects the intolerable circumstances women and their children suffer without the capacity to end a marital relationship, for which economic self-determination is vital. Furthermore, despite Roe v. Wade, sufficient financial independence remains critical to a woman’s ability to obtain an abortion in many states, with some populations residing 100 miles or more from the nearest clinic; only women with sufficient resources, independence and the uncommon privilege of being able to take time off work are able to access these rights (Mogensen, 2018). Women’s lower wages in comparison to men, combined with gendered child care responsibilities, leave women disproportionately at risk for poverty, with women of color at greatest risk (Bleiweis et al., 2020), a situation preconditioned by the lack of an adequate child social safety net and a completely inadequate federal minimum wage. By the time COVID-19 arrived on the world stage, American women were so disadvantaged by depressed wages, a lack of paid leave and a disproportionate burden of childcare that the gender pay gap widened into a “shecession,” in which women have left the workplace in disproportionate numbers and many have been left homeless, wiping out years of workplace gains (Rockeman et al., 2020). As Karen Nussbaum put it in Makers… Part III (2013):

…There was a failure of the women’s movement to focus more on the economic issues of working people. It should have been about creating an alternative that worked for most women, and that alternative would have included child care… community services... [and] after-school care… I think that’s the great failure of the women’s movement.”

In conclusion, the statement “Throughout U.S history a woman’s capacity for economic self-reliance is the most important determinant of her well-being” is well-supported by numerous examples throughout history and remains true today, to the extent that that labor issues are now considered by many to be matters of women’s rights. From the colonial era in which human trafficking and feme covert laws made some women property and dispossessed the privileged remainder, through the period in which women’s education and earning capacity were valued only as a means to educate children, through the tumultuous suffrage era and the time of the working woman in which self-sufficiency was increasingly accessible, the extent to which any woman has been able to obtain and maintain financial self-determination has had a critical influence on her agency and well-being. The extent to which this fact warrants demarcation from labor interests in general is a reflection of women’s historical disenfranchisement and the specific ways in which United States law has been used to disadvantage humanity’s largest minority.

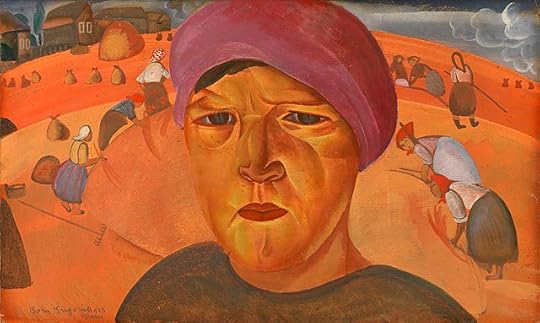

The painting is "Russian Peasant Women, 1923," by Boris Grigoriev (1886-1939)

REFERENCES

Bleiweis, R., Boesch, D., & Gaines, A. C. (2020, August 3). The Basic Facts About Women in Poverty. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/08/03/488536/basic-facts-women-poverty/

Brooks, J. F. (1996). “This Evil Extends Especially ... to the Feminine Sex”: Negotiating Captivity in the New Mexico Borderlands. Feminist Studies 22, 279-309.

Deborah Sampson Cross-Dresses to Fight the British (feat. Evan Rachel Wood) - Drunk History. (2019). Comedy Central. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1tUfxNIlnqY&ab_channel=ComedyCentral

Hening, W. W. (1823). The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 as excerpted in “The Laws of Slavery and Freedom.” New York: R & W & G Barlow.

How America Invented Race | The History of White People in America. (2020). [Animation]. WORLD Channel. Retrieved from https://www.wgbh.org/programs/2020/07/06/the-history-of-white-people-in-america-episode-one-how-america-invented-race

Living Through War and Revolution: Rachel Wells, Petition to Congress. (1786). National Archives.

Makers: Women Who Make America, Part II: Changing the World. (2013). PBS.

Makers: Women Who Make America, Part III: Charting A New Course. (2013). PBS.

Mogensen, J. F. (2018, May 15). This map depicts abortion access across America and it’s really bleak. Mother Jones. Retrieved from https://motherjones.com/politics/2018/05/this-map-depicts-abortion-access-across-america-and-its-really-bleak/

Moody, A. (1992). Coming of Age in Mississippi. Dell.

One Woman, One Vote: American Experience. (1995). PBS.

Phillis Wheatley. (2021, April 9). Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillis_Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley clip from series “Great African American Authors.” (2014). Centre Communications, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ex7mY8HMMnw&ab_channel=ambrosevideo

Rockeman, O., Pickert, R., & Saraiva, C. (2020, September 30). The First Female Recession Threatens to Wipe Out Decades of Progress for U.S. Women. Bloomberg News. News. Retrieved from https://bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-30/u-s-recovery-women-s-job-losses-will-hit-entire-economy

Sotomayor, S. (2013). My Beloved World. Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC.

Ware, S. (2015). American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

June 18, 2021

Short Book Reviews: Kelley Armstrong's Time-travel-Victorian-haunted-house-mystery-romance

A Stitch in Time, by Kelley Armstrong (Subterranean Press)

The author describes A Stitch in Time as a “time-travel-Victorian-haunted-house-mystery-romance,” and it hits all the right notes. History professor Bronwyn inherits the Gothic manor where she lived as a child, and as a summer project embarks upon its renovation. As a child, she was able to step into the manor’s past, where she befriended William, the next heir, until present-day adults decided she was mentally ill and locked her up. So her return is fraught with memories – was William real? – and ghosts that seem to be attempting to communicate with her. Although she’s reluctant to accept it, the time “stitch” keeps returning her to William’s time. So many years have now gone by, and yet the old affection quickly blossoms into something more. Or would, if the ghosts weren’t increasingly importunate. Someone was murdered in William’s time – but who was the victim? And who did it? The more deeply Bronwyn searches, the more dangerous the secrets she uncovers.

All these elements are handled with such superb skill and pacing that I kept turning the pages long after I should have turned out my light. I’m a sucker for a good love story, but when it comes packaged with tantalizing mystery and the wisdom of older-and-wiser characters, the result was a highly satisfying time-travel-and-so-forth adventure.

June 11, 2021

Short Book Reviews: Saving the Prince of the Holy Russian Empire

The Russian Cage, by Charlaine Harris (Gallery / Saga Press)

This is the third installment of the “Gunnie Rose” series, featuring hired gunslinger Lizbeth Rose in an alternate 1930s America in which the United States has fractured into different nations, the West Coast being the Holy Russian Empire. In previous stories (A Longer Fall is reviewed here), Lizbeth encountered, then partnered with and fell in love with, Eli, a gregori (wizard) and Prince of the aforementioned Holy Russian Empire. Their adventures took place in the Southern regions, but now he’s been arrested in San Diego, and Lizbeth sets out to rescue him. As resourceful as she is, and as keen a sharpshooter, nothing has prepared her for the dangerous intricacies of royal court politics, certainly not her previous life, which was poor in material goods but rich with love.

I loved Lizbeth’s first-person voice, a bit Southern-folksy in the manner of Sookie Stackhouse of the True Blood series, but not the same character. Lizbeth has little formal education but a good deal of common sense, kindness, and life experience. While the story moves right along, I most enjoyed the tiny details of Lizbeth’s life. No wonder Prince Eli fell in love with her!

June 10, 2021

[personal] Bragging About My Younger Daughter

(DEIA - Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, & Access)

June 7, 2021

Author Interview: Nancy Jane Moore

Today I chat with Nancy Jane Moore, whose feminist retelling of The Three Musketeers -- For the Good of the Realm -- came out from Aqueduct Press.

Today I chat with Nancy Jane Moore, whose feminist retelling of The Three Musketeers -- For the Good of the Realm -- came out from Aqueduct Press.

Deborah Jean Ross: Tell us a little about yourself. How did you come to be a writer?

Nancy Jane Moore: I grew up in a world in which reading and writing were taken very seriously. My parents were both journalists, so they wrote and edited and had strong opinions about the way other people reported news and wrote stories. When my sister and I were young, my mother would take us to the bookmobile (we lived in the country, so there wasn’t a regular library nearby) to get two weeks worth of books. We’d also grab a box of Hershey’s almond bars at the store and come home to read and eat chocolate.

When I was older, my mother would edit my papers for school, which taught me more about how to write than the work I actually did in class. By the time I finished high school, I had lots of confidence in my basic ability to write.

Two things about reading fiction pushed me toward writing it. First, I came across the occasional story or novel that had a profound effect on me – for example, Doris Lessing’s The Four-Gated City – which made me want to write something that did that for someone else. For all that I read lots of non-fiction, it was always the fiction that inspired that feeling.

Secondly, I spent a lot of time as a teenager reading stories in which I found myself identifying with the main male character because any women in the stories were just there for sex appeal or to tell the man “Don’t go.” I wanted to write stories in which women got to do things. I hope I’ve done that.

DJR: What inspired your book, For the Good of the Realm?

DJR: What inspired your book, For the Good of the Realm? NJM: Some years back, I re-read The Three Musketeersand one of the sequels Dumas wrote, Twenty Years After. After d’Artagnan progressed from a romantic young man to a disillusioned older one, I gave up, but the core story stayed with me. I love adventure stories, but of course the role of women in the Dumas stories was unsatisfying. So I came up with the idea that an all-woman Queen’s Guard should protect the Queen, and went on from there. The short story “A Mere Scutcheon” came first – it’s in my collection Conscientious Inconsistencies – and I finally got around to taking the advice of the editor who bought the collection to expand it into a novel.

DJR: What authors have most influenced your writing? What about them do you find inspiring?

NJM: There have been different ones at different times, but perhaps the most crucial ones were the ones I read starting in 1979. I had complained to a co-worker about the fiction I was reading – for years I described the mainstream/literary fiction of the 1970s as “people living in the Hamptons and getting divorced” – and he said, “You should read C.J. Cherryh.” So I found the first book of the Morgaine series at the local mall bookstore and was hooked. From there I stumbled onto most of the major women science fiction writers of the 1970s and 1980s, both those writing great adventures and those writing incredible feminist fiction. (The feminist science fiction from the 70s was so much better than the mainstream feminist fiction.) I read a few male authors, too – Samuel Delany and William Gibson in particular – but mostly I read Ursula Le Guin, Joanna Russ, James Tiptree, and for awhile everything Cherryh wrote (she was so prolific she got ahead of me). Among other things, they made me realize that if I set a story in the future or in a world that doesn’t exist, I could write about women with agency without spending time explaining how they were able to be that way. That got me started.

DJR: Why do you write what you do, and how does your work differ from others in your genre?

NJM: I love adventure stories, so that’s mostly what I write. I have a pretty broad definition of adventure, but it definitely includes moral dilemmas that require my characters to take a lot of risks. My martial arts training, my feminism, and my politics show up indirectly. Well, the martial arts is sometimes pretty direct – I do like writing fight scenes and particularly enjoyed choreographing the sword fights in For the Good of the Realm.

Some years back, I wrote some short fiction that drew on dreams and my subconscious. It probably falls under “slipstream.” I like doing that in short bursts because it brings out ideas that I’m not truly aware of until I write them down. I don’t think I could write a novel in that style, though. I need a more traditional story to carry me along.

I suspect I differ from others who write science fiction and fantasy adventures more in terms of tone than in any more concrete way. My stories sound like my stories, regardless of what subset of the genre they fit in.

DJR: How does your writing process work?

NJM: I’m a pantser, through and through. I get an idea and start writing until I get to the point where I figure out what the story is about. If it turns out to be long, I will eventually make notes about where it’s going, but I don’t outline.

DJR: What have you written recently? What lies ahead?

NJM: I’ve got a couple of longish short stories I’ve been working on this spring. Beyond that, I’ve got the beginning of a sequel to For the Good of the Realm, which I need to get back to. And then there’s this generation ship novel, which is a project of my heart. It started out as a short story in response to one of my favorite stories – Joanna Russ’s “When It Changed” – but it’s become clear that I’m going to need a whole book to address what she did in about five thousand words.

DJR: What’s the strangest or most touching fan mail you’ve ever received?

NJM: Back in 2011, I got an email from someone who had read both a short story and an essay I had in a volume of the WisCon Chronicles, the anthology Aqueduct Press put out for a number of years reporting on events at the WisCon science fiction convention in Madison. It began, “Are you my long-lost twin sister” because the writer felt such connection in reading my work. It was a nice letter, so I wrote back. We corresponded for a year before meeting in person at the next WisCon. In 2014, I moved to Oakland to live with him.

DJR: What advice would you give an aspiring writer?

NJM: Figure out what you mean by being a writer and what you ultimately want out of your writing career. There are so many different ways of going about being a writer and there’s no one right path for everyone.

First of all, what do you really want to write? I always wanted to write my own stories, but lots of other writers like doing novelizations or writing in shared universes. Some like doing comics. Others like writing for games or movies or television, which can be more collaborative. Some do more than one thing, though since almost all of these fields have some barriers to entry, I think focusing on the one that is most important to you in the beginning is important. Later, if you have some reputation, you may be able to expand. I notice that a lot of well-known SF/F writers get asked to write for comics franchises, for example, and some are working on scripts as well.

If you are willing to learn the business side – both production and sales – self publishing is a reasonable path these days. The big publishers are still going strong, but only a few people are making enough money from those contracts to make that their primary job. There are lots of small presses – I publish with a good one – but there is not a lot of money in that. So part of the decision is how much money you need and want to make from writing fiction.

I know I had the dream of quitting my day job to write fiction when I was younger. I never managed to do it, but what I did manage to do was find a day job that left me with the energy to write on the side. In my case, that was also a writing job – legal editing and reporting. I found it very useful because doing any kind of writing teaches you about how to put together good sentences and explain things clearlyand also because it was intellectually stimulating without being emotionally taxing. In the end, I’m glad it worked that way, because I never had to try to make my fiction commercial enough to support myself.

But here’s the thing: the right choice for me might not be the right choice for you. The main thing is to do the work that you want to do, tell the stories that only you can tell in the way that only you can tell them. There’s a huge variety of ways to do that. Find the one that works for you.

Nancy Jane Moore is the author of the fantasy novel For the Good of the Realm and the Locus-recommended science fiction novel The Weave, both published by Seattle’s Aqueduct Press. Her other books include the novella Changeling and the collection Conscientious Inconsistencies. Her short stories have appeared in numerous anthologies and in magazines ranging from the National Law Journal to Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. In addition to writing, she holds a fourth degree black belt in Aikido and teaches empowerment self defense. A native Texan who spent many years in Washington, D.C., she now lives in Oakland, California, with her sweetheart, two cats, and an ever-growing murder of crows. Twitter: @WriterNancyJane; blog: https://treehousewriters.com/wp53/; website: http://nancyjanemoore.com/.

Nancy Jane Moore is the author of the fantasy novel For the Good of the Realm and the Locus-recommended science fiction novel The Weave, both published by Seattle’s Aqueduct Press. Her other books include the novella Changeling and the collection Conscientious Inconsistencies. Her short stories have appeared in numerous anthologies and in magazines ranging from the National Law Journal to Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. In addition to writing, she holds a fourth degree black belt in Aikido and teaches empowerment self defense. A native Texan who spent many years in Washington, D.C., she now lives in Oakland, California, with her sweetheart, two cats, and an ever-growing murder of crows. Twitter: @WriterNancyJane; blog: https://treehousewriters.com/wp53/; website: http://nancyjanemoore.com/.

June 4, 2021

Book Reviews: The Two (Women) Musketeers

For the Good of the Realm, by Nancy Jane Moore (Aqueduct)

The elevator pitch for this charming historical fantasy is “The Three Musketeers With Women.” That does not do justice to the book by a long shot. The concept is familiar enough, from both the novels by Alexandre Dumas and the many film adaptations. In this swashbuckler tale, heroic, chivalrous swordsmen fight for justice and for their unbreakable friendship. The original, written in 1844, featured men in all the fun roles, with women being either weepy and weak or deviously evil. But why should the men have all the fun? I expect just about every female reader or viewer has railed at the injustice of depriving half the human race of such valorous deeds. Nancy Jane Moore, a thoughtful writer and skilled martial artist, has now set things right.

For the Good of the Realm is and isn’t like The Three Musketeers. There’s a realm like France, a royal couple divided by politics, each served by their own dedicated guard, and the head of the Church bent on cementing their own power. In this world, however, the Queen’s Guard is comprised of women, and the King’s Guard of men, and the queen’s advisors are largely women, as is the Hierophante. Add to this the existence of magic, condemned by the Church, arousing superstitious dread but freely used by the enemies of the Realm. There is no green recruit, D’Artagnan, but a pair of women friends from the Queen’s Guard – Anna D’Gart and Aramis, who fights duels as an amusement and cannot quite seem to give up her bawdy relations to become a priest. Each has a lover from the King’s Guard from whom they must keep secrets, but with whom they occasionally join forces.

The structure of this novel reflects the style to which it does homage. The point of view straddles the divide between third and omniscient, less intimate than is currently in vogue but marvelously evocative of Dumas and his contemporaries. Moore’s control of language and tone never falters as she draws the reader into not only a different world but a slightly different way of experiencing that world. Today we confuse “closeness” in point of view with emotional closeness to a character, but as Dumas and now Moore demonstrate, readers can feel very much in touch with a character through the careful depiction of actions and words. This is, after all, how we come to understand the people in our lives. “The adventures of…” implies an episodic arrangement, but here each chapter and each incident builds on what has come before and lays the foundation for what is to come in subtle, complex ways. The final confrontation between Anna d’Gart and the evil, scheming Hierophante is less a Death Star explosion than it is the inevitable showdown between two highly competent chess players.

In reflecting on the pleasure of immersing myself in For the Good of the Realm, it strikes me as a tapestry created by a master weaver. There is an overall picture but the intricate details and skill of the stitchery – the lives and relationships of the characters – are what lend it depth and resonance.

Order it from Amazon here or from your favorite bookstore.