Deborah J. Ross's Blog, page 138

October 18, 2013

GUEST BLOG: Janet Freeman on Gratitude and Stewardship

I was awed and inspired by how fully my friend lived the almost-five years between her diagnosis with Stage 4 ovarian cancer and her death last week. I am reminded that a terminal diagnosis does not mean we stop living -- it is an invitation to make every moment count, and thereby enrich not only the life of the patient but those around her. Here is author and lung cancer patient Janet Freeman-Daily on her own experience of hope, illness, and the zest of being alive.

I’m grateful to be here. Actually, I’m grateful to be anywhere. I’m grateful to be alive. The fact that I’m alive is a modern-day medical miracle.

In May of 2011, after a few months of a persistent cough, I was

diagnosed with pneumonia caused by advanced lung cancer. No, I never

smoked anything except a salmon. Five months after diagnosis, despite

chemo and radiation, the cancer spread outside my chest and I was given

at most two years to live. A year later, after more treatment and

another recurrence, I learned my cancer had a rare mutation. Last

October, I found a clinical trial that could treat that mutation with an

experimental pill, and I flew to Denver to get it. In January, I

achieved the dream of all metastatic cancer patients: No Evidence of

Disease. My cancer is no longer detectable.

I am overwhelmingly grateful for everything and everyone that has

brought me to this state of grace: medical science that discovered new

ways to treat my condition, insurance that paid for most of my care,

family and friends who supported me, a knowledgeable online lung cancer

community, and all the prayers and good wishes lifting me up throughout

my cancer journey. Thank you. I am truly blessed.

I am not cured. The tri

al drug only suppresses my cancer, and I

have some permanent side effects. I’ll be in treatment for the rest of

my days. Clinical trials will hopefully keep me feeling comfortable

and capable for many months – even years. I am satisfied with living

however long I might have.

Being given a second chance at life tends to give one a different

perspective. Colors are brighter. A warm breeze rustling the trees

makes the whole day worthwhile. Time spent with family and friends

becomes precious.

A second chance at life also makes one introspective. Why was I

spared when others died? Why does my mutation have an effective

treatment when others don’t? Why am I able to see one of the best lung

cancer doctors in the world when many patients can’t afford proper

treatment?

Why am I still here? What purpose does the universe have for me?

Part of the answer to why I’m still here is, I am blessed with gifts

that help me survive my cancer journey. I’m able to understand the

medical science and my treatment. I’m able to explain what I’ve

learned. And I’m able to advocate for myself with healthcare providers.

Yet I am just a steward of these gifts that were bestowed on me.

Understanding my gifts has led me to a new purpose: I am here to help

other lung cancer patients. I strongly feel this is my calling in the

time I have left.

Lung cancer has a stigma attached to it. Few people know that 80% of

those newly diagnosed with lung cancer are nonsmokers or never

smokers. There is more to lung cancer than just smoking. Yet we are

the lepers of the cancer community.

For this reason, some are ashamed to admit they have lung cancer.

Most don’t know about the new treatments like the one I’m taking–even

some doctors don’t know. Patients don’t know where to turn for answers.

Lung cancer patients need more than compassion. They need information. They need HOPE.

After considerable thought, I decided the best way to use my gifts

was to go public about my lung cancer. At first, I only shared my story

online with friends and lung cancer communities. Eventually I started

blogging (which is essentially a journal open to the world on the

Internet) and began speaking publicly about my cancer.

Going public with my lung cancer experience has already had an

impact. As I’d hoped, it shows patients that people can live with

metastatic lung cancer, and encourages them to ask questions about their

treatment.

But going public has also brought completely unexpected benefits. It

helps families understand what their loved ones who have lung cancer are

experiencing. It gives hospital chaplains insight into their patients’

needs and feelings. It demonstrates to doctors that patients can be

partners in their own care. It reveals to researchers how their work

makes a difference in the lives of real patients.

In addition, I’ve realized a personal health benefit in sharing the

gifts I was given to steward. Having a purpose gets me through the

tougher parts of cancer treatment. It won’t heal my cancer, but it does

help me live a healthier, happier life.

And it all started with being grateful that I’m alive.

~o0o~

About herself, Janet says: "I’ve made a career as a “technical translator” of

sorts: I research a

scientific or engineering subject, describe it to others in less

technical terms, and help them understand how this new gizmo could

benefit them. I applied my engineering degrees (MIT SBME 1978, Caltech

Aeronautics MS 1984 and Engineer 1986) to a career in aerospace systems

engineering for two decades, interacting with customers, developing new

products and writing proposals. I spent over 12 years caring for

elderly family members who had dementia. My adult son, who I adopted

when he was three, is on the autism spectrum. I now write science

articles and science fiction, sometimes under the pen name “Janet

Freeman,” and speak on science panels at science fiction conventions,

where I’m told I “give good science.”

Her blog is here.http://grayconnections.wordpress.com/

I’m grateful to be here. Actually, I’m grateful to be anywhere. I’m grateful to be alive. The fact that I’m alive is a modern-day medical miracle.

In May of 2011, after a few months of a persistent cough, I was

diagnosed with pneumonia caused by advanced lung cancer. No, I never

smoked anything except a salmon. Five months after diagnosis, despite

chemo and radiation, the cancer spread outside my chest and I was given

at most two years to live. A year later, after more treatment and

another recurrence, I learned my cancer had a rare mutation. Last

October, I found a clinical trial that could treat that mutation with an

experimental pill, and I flew to Denver to get it. In January, I

achieved the dream of all metastatic cancer patients: No Evidence of

Disease. My cancer is no longer detectable.

I am overwhelmingly grateful for everything and everyone that has

brought me to this state of grace: medical science that discovered new

ways to treat my condition, insurance that paid for most of my care,

family and friends who supported me, a knowledgeable online lung cancer

community, and all the prayers and good wishes lifting me up throughout

my cancer journey. Thank you. I am truly blessed.

I am not cured. The tri

al drug only suppresses my cancer, and I

have some permanent side effects. I’ll be in treatment for the rest of

my days. Clinical trials will hopefully keep me feeling comfortable

and capable for many months – even years. I am satisfied with living

however long I might have.

Being given a second chance at life tends to give one a different

perspective. Colors are brighter. A warm breeze rustling the trees

makes the whole day worthwhile. Time spent with family and friends

becomes precious.

A second chance at life also makes one introspective. Why was I

spared when others died? Why does my mutation have an effective

treatment when others don’t? Why am I able to see one of the best lung

cancer doctors in the world when many patients can’t afford proper

treatment?

Why am I still here? What purpose does the universe have for me?

Part of the answer to why I’m still here is, I am blessed with gifts

that help me survive my cancer journey. I’m able to understand the

medical science and my treatment. I’m able to explain what I’ve

learned. And I’m able to advocate for myself with healthcare providers.

Yet I am just a steward of these gifts that were bestowed on me.

Understanding my gifts has led me to a new purpose: I am here to help

other lung cancer patients. I strongly feel this is my calling in the

time I have left.

Lung cancer has a stigma attached to it. Few people know that 80% of

those newly diagnosed with lung cancer are nonsmokers or never

smokers. There is more to lung cancer than just smoking. Yet we are

the lepers of the cancer community.

For this reason, some are ashamed to admit they have lung cancer.

Most don’t know about the new treatments like the one I’m taking–even

some doctors don’t know. Patients don’t know where to turn for answers.

Lung cancer patients need more than compassion. They need information. They need HOPE.

After considerable thought, I decided the best way to use my gifts

was to go public about my lung cancer. At first, I only shared my story

online with friends and lung cancer communities. Eventually I started

blogging (which is essentially a journal open to the world on the

Internet) and began speaking publicly about my cancer.

Going public with my lung cancer experience has already had an

impact. As I’d hoped, it shows patients that people can live with

metastatic lung cancer, and encourages them to ask questions about their

treatment.

But going public has also brought completely unexpected benefits. It

helps families understand what their loved ones who have lung cancer are

experiencing. It gives hospital chaplains insight into their patients’

needs and feelings. It demonstrates to doctors that patients can be

partners in their own care. It reveals to researchers how their work

makes a difference in the lives of real patients.

In addition, I’ve realized a personal health benefit in sharing the

gifts I was given to steward. Having a purpose gets me through the

tougher parts of cancer treatment. It won’t heal my cancer, but it does

help me live a healthier, happier life.

And it all started with being grateful that I’m alive.

~o0o~

About herself, Janet says: "I’ve made a career as a “technical translator” of

sorts: I research a

scientific or engineering subject, describe it to others in less

technical terms, and help them understand how this new gizmo could

benefit them. I applied my engineering degrees (MIT SBME 1978, Caltech

Aeronautics MS 1984 and Engineer 1986) to a career in aerospace systems

engineering for two decades, interacting with customers, developing new

products and writing proposals. I spent over 12 years caring for

elderly family members who had dementia. My adult son, who I adopted

when he was three, is on the autism spectrum. I now write science

articles and science fiction, sometimes under the pen name “Janet

Freeman,” and speak on science panels at science fiction conventions,

where I’m told I “give good science.”

Her blog is here.http://grayconnections.wordpress.com/

Published on October 18, 2013 01:00

October 15, 2013

BOOK RELEASE! Mad Science Cafe (anthology)

My latest anthology, from Book View Cafe!

From the age of steam and the heirs of Dr. Frankenstein to the asteroid

belt to the halls of Miskatonic University, the writers at Book View

Café have concocted a beakerful of quaint, dangerous, sexy, clueless,

genius, insane scientists, their assistants (sometimes equally if not

even more deranged, not to mention bizarre), friends, test subjects, and

adversaries.

Table of Contents:

The Jacobean Time Machine, by Chris Dolley

Comparison of Efficacy Rates, by Marie Brennan

A Princess of Wittgenstein, by Jennifer Stevenson

Mandelbrot Moldrot, by Lois Gresh

Dog Star, by Jeffrey A. Carver

Secundus, by Brenda W. Clough

Willie, by Madeleine E. Robins

One Night in O’Shaughnessy’s Bar, by David D. Levine

Revision, by Nancy Jane Moore

Night Without Darkness, by Shannon Page & Mark J. Ferrari

The Stink of Reality, by Irene Radford

“Value For O,” by Jennifer Stevenson

The Peculiar Case of Sir Willoughby Smythe, by Judith Tarr

The Gods That Men Don’t See, by Amy Sterling Casil

You can download a sample from the BVC bookstore, too. This anthology includes both original and reprint stories and is available as mobi and epub formats, so you can download the version that's right for your ereader. Best of all, because BVC is an author's publishing cooperative, 95% of the price goes to the authors themselves.

Published on October 15, 2013 01:00

October 14, 2013

Book View Cafe Editor Interview

Over at Book View Cafe blog, Katharine Eliska Kimbriel interview me "with my editor hat on."

When did you become interested in editing other writers’ work as opposed to concentrating on writing?

I first started thinking about editing during the years when I’d

visit Marion Zimmer Bradley on a regular basis. I helped read slush for

her magazine (MZB’s Fantasy Magazine) and

we’d talk. I got a “behind the scenes” look at what she looked for and

why, and how she handled rejection letters. She taught me that the work

of an editor isn’t mysterious, in part because her own tastes were so

definite. A story could be perfectly good but not suit the anthology or

magazine she was reading for, or might do both but not “catch fire” for

her. I learned about “no fault” rejections (and I’ve received them

myself, for example if the editor had just bought a story on the same

theme by a Big Name Author) and that sometimes if an editor thought the

story had merit but didn’t fulfill its promise, she could comment on its

shortcomings or issue an invitation to re-submit after revision. I

thought, “I can do this!” I’d had so many experiences from the Author

side of the desk, I approached editing with a set of wild hopes and

convictions.

What are the special challenges of editing in a shared world as opposed to a theme anthology?

I think the crucial thing is a solid idea about how rigid (or

conversely how flexible) the structure is. The more rigid, the deeper

into the slush pile you’re going to have to dig (assuming it’s open

submission) or the more you’re going to risk throttling the creative

vision of your writers. So you need to be clear about what’s essential.

For example, if I were editing a Star Wars anthology and a writer

submitted a story that was essentially a bodice-ripper, no matter how

excellently done, I’d have to turn it down. That’s too great a violation

of the parameters. Just as with an individually-authored work, you’re

making a contract with your reader. Put your imagination in my/our hands

and this is the kind of experience you’ll have. (Not that there

won’t be surprises; good writing abounds in unexpected twists and

conventions-turned-upside-down.)

On the other hand, many shared worlds

offer latitude for “alternate versions,” especially when told from the

point of view of a not-entirely-reliable narrator. For myself, I would

rather see a story that bends the rules a little but does so in the

service of the clarity and passion of the author’s vision, than a

lifeless one that conforms strictly, one that follows the letter but not

the spirit of the guidelines. I suspect Marion influenced me in this

because she herself never let previously-established details get in the

way of a really good story.

Read more here.

Published on October 14, 2013 12:53

October 11, 2013

ARCHVES: Murder, the Death Penalty, and Cancer

Because I'll be busy helping with my friend's memorial and other family issues, I'm reposting something from a couple of years ago. Yes, Bonnie is the friend I mention.

Twenty-five years ago, my mother was raped and beaten to death by a

teenaged neighbor on drugs. My mother was 70 years old and had been his

friend since the time he was a small child. For a long time, I didn't

talk much about it except in private situations. This was not to keep it

a secret, but to compartmentalize my life so I could function. At

first, it was too difficult and then, as the years passed, I refused to

let this single incident be the defining experience of my life.

Recently, however, I have felt inspired to use my own experience of

survival and healing to speak out against the death penalty. I don't

write this to convince you one way or another on that particular issue,

but to try to illuminate how the two issues are related for me.

My

mother's murder was a spectacularly brutal, headline-banner crime, but

it was only part of a larger tragedy, for the perpetrator's family had

suffered the murder of his older brother some years before. I knew this,

but for a long time it didn't matter. My own pain and rage took center

stage. But with time and much hard work in recovery, I came to the place

of being able to listen to the stories of other people.

We

all lose people we love. Tolstoy wrote that happy families are all

alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. I would

interpret that to mean that each loss, each set of relationships and

circumstances is unique, but there are things we share.

What

might it be like if one family member were murdered -- and another

family member had killed someone? What does it feel like to watch the

weeks and days pass while the execution of someone you dearly love draws

ever nearer? How can we wrap our minds around loving someone and

accepting that they have caused such anguish to another family? I've had

a chance to talk with people in all these circumstances. It's been a

humbling experience.

One

thing I have learned over the years is that grief isn't fungible; you

can't compare or exchange one person's experience with another's or say,

This one's pain is two-thirds the value of that one's. Grief is grief;

loss is loss. We cannot truly understand what another's loss is like,

especially when it is as devastating and life-altering as the violent

death of someone we love. But we can say, "Even though I don't know what

you're going through, my heart goes out to you." Whatever our personal

story, we can be allies, for surely there is enough compassion, enough

tears, enough rage and enough mending of hearts to go around.

I've

been on both sides. I believe we have something deep and essential in

common -- our broken hearts. Our mending hearts. Our resilient spirits.

Our capacity for healing. Our journey through the darkness. I know that I

would never, ever want to be part of inflicting what I have endured on

another family. I know that life is filled with awful things, and I have

faith that kindness lightens grief. I believe all these things are true

whether we are the survivors of a murder, victims ourselves, loved ones

of perpetrators, or the families of the executed.

What

this has to do with cancer is that right now, by the inexplicable way

life unfolds, a number of friends -- some of them very close to me --

have been battling various forms of cancer. Here there is no human

malice or sudden tragedy, one moment you're fully alive and the next,

everything is over. The breakdown of order and health is internal and

continues over time. Even in cases where the end comes soon after the

diagnosis, it is not instantaneous. You have time, if even a small

stretch, to consider your own mortality. And so do those who care for

you.

I find I am as angry about the possibility of my

friends dying from cancer as I am about losing a loved one to violence. I

want to rage at the universe at the unfairness and unfeelingness of it

all. I wish there were an old man with a long white beard up in the sky

so I could grab him by that beard and let him have a piece of my mind.

I look for someone or something to blame.

In

the case of a murder conviction, there is someone to blame. The jury

said so or the person admitted it in pleading guilty. In the case of

cancer, I don't believe in blaming the victim -- he smoked, she didn't

exercise, he ate too many charbroiled steaks and not enough broccoli,

she lived near a cellphone tower. Justice demands that we hold those who

commit crimes accountable. What do we do with the craving for revenge

in our hearts? Or, in the case of cancer, the need to point a finger of

blame -- at the patient, at the doctors, at the pharmaceutical

companies, at the health insurance carriers.

In

neither case will my retaliation bring a loved one back to life or

affect the course of a friend's disease. In both cases, I myself become a

victim. The impulse to lash out at the responsible person or

institution is universal and human. Adrenaline helps us through the

early stages of shock and helpless immobility. When it goes on too long,

however, it consumes us from within and prevents us from being present

in the moment.

I could spend 25 years dedicating my

life to ending that of the man who killed my mother. Or I could spend 25

years healing, connecting to life, making the world a better place,

writing wonderful stories...being the person she would have wanted me to

be.

I could spend the months and years of my friend's

cancer in expectant grief and one crusade after another against

anything and anyone who isn't finding a cure fast enough. Or I could be

present with her, each of us alive at this moment.

~o0o~

If my posts have been meaningful to you, I hope you'll check out my fiction as well, particularly The Seven-Petaled Shield, in which grief, devotion, and revenge pay pivotal roles.

Twenty-five years ago, my mother was raped and beaten to death by a

teenaged neighbor on drugs. My mother was 70 years old and had been his

friend since the time he was a small child. For a long time, I didn't

talk much about it except in private situations. This was not to keep it

a secret, but to compartmentalize my life so I could function. At

first, it was too difficult and then, as the years passed, I refused to

let this single incident be the defining experience of my life.

Recently, however, I have felt inspired to use my own experience of

survival and healing to speak out against the death penalty. I don't

write this to convince you one way or another on that particular issue,

but to try to illuminate how the two issues are related for me.

My

mother's murder was a spectacularly brutal, headline-banner crime, but

it was only part of a larger tragedy, for the perpetrator's family had

suffered the murder of his older brother some years before. I knew this,

but for a long time it didn't matter. My own pain and rage took center

stage. But with time and much hard work in recovery, I came to the place

of being able to listen to the stories of other people.

We

all lose people we love. Tolstoy wrote that happy families are all

alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. I would

interpret that to mean that each loss, each set of relationships and

circumstances is unique, but there are things we share.

What

might it be like if one family member were murdered -- and another

family member had killed someone? What does it feel like to watch the

weeks and days pass while the execution of someone you dearly love draws

ever nearer? How can we wrap our minds around loving someone and

accepting that they have caused such anguish to another family? I've had

a chance to talk with people in all these circumstances. It's been a

humbling experience.

One

thing I have learned over the years is that grief isn't fungible; you

can't compare or exchange one person's experience with another's or say,

This one's pain is two-thirds the value of that one's. Grief is grief;

loss is loss. We cannot truly understand what another's loss is like,

especially when it is as devastating and life-altering as the violent

death of someone we love. But we can say, "Even though I don't know what

you're going through, my heart goes out to you." Whatever our personal

story, we can be allies, for surely there is enough compassion, enough

tears, enough rage and enough mending of hearts to go around.

I've

been on both sides. I believe we have something deep and essential in

common -- our broken hearts. Our mending hearts. Our resilient spirits.

Our capacity for healing. Our journey through the darkness. I know that I

would never, ever want to be part of inflicting what I have endured on

another family. I know that life is filled with awful things, and I have

faith that kindness lightens grief. I believe all these things are true

whether we are the survivors of a murder, victims ourselves, loved ones

of perpetrators, or the families of the executed.

What

this has to do with cancer is that right now, by the inexplicable way

life unfolds, a number of friends -- some of them very close to me --

have been battling various forms of cancer. Here there is no human

malice or sudden tragedy, one moment you're fully alive and the next,

everything is over. The breakdown of order and health is internal and

continues over time. Even in cases where the end comes soon after the

diagnosis, it is not instantaneous. You have time, if even a small

stretch, to consider your own mortality. And so do those who care for

you.

I find I am as angry about the possibility of my

friends dying from cancer as I am about losing a loved one to violence. I

want to rage at the universe at the unfairness and unfeelingness of it

all. I wish there were an old man with a long white beard up in the sky

so I could grab him by that beard and let him have a piece of my mind.

I look for someone or something to blame.

In

the case of a murder conviction, there is someone to blame. The jury

said so or the person admitted it in pleading guilty. In the case of

cancer, I don't believe in blaming the victim -- he smoked, she didn't

exercise, he ate too many charbroiled steaks and not enough broccoli,

she lived near a cellphone tower. Justice demands that we hold those who

commit crimes accountable. What do we do with the craving for revenge

in our hearts? Or, in the case of cancer, the need to point a finger of

blame -- at the patient, at the doctors, at the pharmaceutical

companies, at the health insurance carriers.

In

neither case will my retaliation bring a loved one back to life or

affect the course of a friend's disease. In both cases, I myself become a

victim. The impulse to lash out at the responsible person or

institution is universal and human. Adrenaline helps us through the

early stages of shock and helpless immobility. When it goes on too long,

however, it consumes us from within and prevents us from being present

in the moment.

I could spend 25 years dedicating my

life to ending that of the man who killed my mother. Or I could spend 25

years healing, connecting to life, making the world a better place,

writing wonderful stories...being the person she would have wanted me to

be.

I could spend the months and years of my friend's

cancer in expectant grief and one crusade after another against

anything and anyone who isn't finding a cure fast enough. Or I could be

present with her, each of us alive at this moment.

~o0o~

If my posts have been meaningful to you, I hope you'll check out my fiction as well, particularly The Seven-Petaled Shield, in which grief, devotion, and revenge pay pivotal roles.

Published on October 11, 2013 01:00

October 8, 2013

Go in grace, dear friend

Published on October 08, 2013 14:28

October 7, 2013

What I’m Reading – The Hospice Edition

When I packed to travel out of state to help care for my

best friend and her family during her final weeks of life, I had no idea how

long I would be away. The ereader my daughter had passed on to me provided the

ideal solution of how to carry a variety of books with me. I read at night as

part of my bedtime ritual and I couldn’t anticipate what I would need at the

end of each day. Horror, which has never previously appealed to me, might resonate

with the depth of the grief of this entire household as we let go of hope and

say goodbye. Maybe not, but should I bring some just in case? What about my

favorite and unabashedly unguilty pleasures – fantasy and science fiction?

Something to challenge my mind and make me think? A genre I don’t usually read?

Mystery? Nonfiction?

I loaded up my ereader with a stack of books from Book View Café,

picking a few from authors I’ve loved and choosing others practically at

random. Here’s what I’ve been reading and why.

I started with three pieces – two novellas and a novel -- by

I started with three pieces – two novellas and a novel -- byMarie Brennan. I’d never read her work before she joined Book View Café, so

when I found Midnight Never Come in a

bookstore (and it looked interesting), I grabbed it. It’s the first of a series

called “The Onyx Court,” set London during the reign of Elizabeth I. My husband and

I had gone through a phase of watching every film biography of Elizabeth I that

we could find, so that was an automatic plus. Brennan created a second, faerie

court, hidden belowground but interacting in secret ways for England’s benefit.

Fits right in with Sir Francis Walsingham and Dr. John Dee, and other

historical characters. I enjoyed the book immensely, so the first thing I read

was more Brennan, a novella set in the same world although slightly later in time.

Deeds of Men is a murder mystery,

with characteristic Brennan twists. I was glad I’d already read Midnight Never Come because I was

already in love with the main character, but this would also make a good

introduction to the series. I also picked the two “Welton” pieces, a prequel

novella called Welcome To Welton and

then the novel Lies and Prophecy.

Both reminded me a little of Pamela Dean’s excellent Tam Lin, only set at Hogwarts if Hogwarts was a college and magic

was public and widely spread. What kind of curriculum would a college offer?

Dorms, room mates, cafeteria food, professors, meddling parents, the whole

shebang. But Brennan doesn’t leave the story there; it turns out that the

reason people have magical abilities is that they’re descended from fae who

mingled with humans during a time when Faerie was closer to Earth. And now the

two worlds are drawing closer again, and the Seelie and UnSeelie Courts are in deadly

competition for who gets to rule, whether to enslave or ally with humans. And

our college kids are caught up in it all. Brennan’s easy prose and likeable characters

drew me into her world, a lovely escape at the end of each day.

Why, oh why, did I wait so long to read Chris Dolley’s What Ho, Automaton! ? Obviously because I

needed to have not only read P. G. Wodehouse, but have seen the hilarious Jeeves and Wooster with Hugh Laurie and

Stephen Fry. Transport the impeccable “gentleman’s gentleman” into a “gentleman’s

gentleautomaton” and give poor Bertie Wooster a few more brain cells – but not

too many – and you have a delightful, pitch-perfect series of adventures.

Steampunk with class and mannered style!

After that, I flipped to the beginning of the alphabet with

After that, I flipped to the beginning of the alphabet withPatricia Rice’s All A Woman Wants.There’s a certain delight in having no expectations of what I’m about to dive

into. This is a Regency Romance, and while I have read Jane Austen’s novels

about a gazillion times (not to mention another marathon of watching the movie

versions), I’m not a Romance reader. The covers turn into pretty much impenetrable

barriers. I decided to give this one a go. To my not-so-great surprise, I

enjoyed both the setting and the dance of attraction and complication between

the two main characters. There were times when I wanted to grab each of them by

the lapels and scream, “Will you get off it and admit you’re in love with each

other?” The question isn’t whether they will do that – we know they will at the

end of the book, but how they get there.

So we’ve got an American sea captain who’s just kidnapped his late sister’s two

kids from their abusive but aristocratic dad, and a newly-orphaned spinster who’s

trying to run a sizeable estate with no education or training but a good deal

of determination and compassion. While waiting for his ship to be ready to hie

him back to Virginia, he hides the kids from the aforementioned deadbeat drunkard-but-powerfully-connected

dad at her estate in exchange for teaching her how to run the place herself. I

loved her insistence on wanting to learn, to understand and be truly independent,

and I often laughed aloud at how he could be so competent in one area and yet

fall apart at the prospect of dealing with two utterly charming hellion kids,

not to mention a woman who insists on “worrying her pretty head” about her responsibilities.

At the end, I came to a new appreciation of how soothing it can be to immerse

myself in a time and situation where love does prevail, but not at the cost of

integrity for both parties.

Also in the A’s I spied a couple of Judith Tarr novels and

selected one at random, Arrows of the Sun.

I was pleased to see it was Book I of something but not until I finished did I

discover it was Book I of a second trilogy. This is important because I still

had a wonderful, satisfying reading experience. So many long series assume you

are going to start at the very beginning and not skip a volume. I know readers

who won’t even start a new series until they have all the books in hand. I

guess they’ve been burned by authors who, for one reason or another, fail to

finish a series or fail to do so in a timely manner. This book, while

undoubtedly related to the others I have yet to enjoy, stands beautifully on

its own. It’s got so many of the elements I love in a fantasy: a strong woman

character (more than one, each in her own way!), a conflicted, sensual, earnest

male character, cool horse-like creatures (with horns!) and even cooler

cat-like things, magic and mages and interdimentional Gates, oh my! And plot

twists, lots of flavors of sexuality and love, jealousy and generosity, and characters

that turn out to be not at all what I expected. I won’t offer any more

specifics for fear of spoiling the show. The only thing left to decide is

whether to go back to the first book of the first

trilogy or to continue with this one.

Next up was Vonda N. McIntyre’s delightful and essential Pitfalls of Writing Science Fiction and Fantasy , a

collection of short and pithy essays from a master in the field. In fact, with

a few variations, I’d feel safe in saying it should be required reading for all

writers.

Ready for another leap into the unknown, I picked a new author

and a book I knew nothing about: Girl’sGuide to Witchcraft by Mindy Klasky. Having worked in a college library and

revamped one for a local elementary school, I’m a total sucker for librarians

as hero/ines. Librarians are my heroes, any day of the week. A fun, breezy

style, immediately likeable characters . . . I’m hooked. Hooray! There are more

in the “Jane Madison” series!

I hope you’ll check out some of these books and many more (and maybe some

of my own, also at Book View Café).

Published on October 07, 2013 01:00

October 5, 2013

Friendship as living water

At last we've had some sun, after days of storm and gloomy overcast. Hospice sent a lovely volunteer to sit with my friend, so I took a break and spent the afternoon talking shop and getting my creative batteries "recharged" with a nearby fellow writer. I'm reminded how friends create a network as resilient as any spun by a spider. Friendships work because we're not all crazy -- or needy, or sick -- on the same day. Our love for one another is like water flowing through many channels, all one thing but divided, some sleepy winding rivers or placid waves on the beach, others torrential downpours or waterfalls, or glaciers. Or tsunamis.

Published on October 05, 2013 21:24

October 4, 2013

GUEST BLOG: Katharine Kerr on Writing Long Series

Saga, Series, and Just Plain Long Books

There is nothing an author today has to guard himself

more carefully against than the Saga Habit.

The least slackening of vigilance and the thing has gripped him.

-- P.G.

Wodehouse, writing in 1935

How little

things change! I too am a victim of the

Saga Habit. Fifteen Deverry books, four

Nola O’Gradys -- and I haven’t even finished the Nola series! Now SORCERER’S LUCK, which I a “Runemaster trilogy”. Over the years, a number of people have asked

me why I tend to write at this great length.

I’ve put some thought into the answer, and it can be boiled down one

word: consequences. Well, maybe two

words: consequences and characters. Or

perhaps, consequences, characters, and the subconscious mind, above all the

subconscious mind. You see what I

mean? These things multiply by

themselves.

meant to be a

stand-alone, is insisting that it’s only the first volume of

Not all

series books are sagas. Some are shaped

more like beads on a string, separate episodes held together by a set of

characters, who may or may not grow and change as the series continues. Many mystery novels fall into the episode

category, Sherlock Holmes, for example, or James Bond. Other series start out as episodics, but saga

creeps up on them as minor characters bring depth to a plot and demand stories

of their own, for instance, in Lois McMaster Bujold’s Miles Vorkosigan series

or Ian Rankin’s detective novels. What

determines the difference in these examples comes back to the idea of

consequences.

James Bond

can kill people, blow up large portions of real estate, see yet another

girlfriend die horribly -- and have nothing in particular happen as a

consequence, at least, not that the reader or viewer ever learns. I’ve always imagined that a large,

well-financed insurance team comes along after him, squaring everything with

the locals, but we never see that.

Consider, too, Hercule Poirot or other classic detectives in the crime

novel category. They do not grow and

change because they’re a collection of tics and habits. I don’t mean to imply that there’s something

wrong with this, or that episodic works are somehow inferior to sagas. I’m merely pointing out the difference.

An actual

saga demands change, both in its characters and its world. Often the innocent writer starts out by

thinking she’s going to write some simple, stand-alone story, set maybe in a

familiar world, only to find the big guns -- consquence, character, and the

subconscious -- aimed directly at her.

Sagas hijack the writer. At least

they do me.

A good

example is the Deverry series. Back in

1982, I decided to write a fantasy short story about a woman warrior in an

imaginary country. It turned into a

novella before I finished a first draft.

It was also awful -- badly written, undeveloped, pompous. The main character came across as a cardboard

gaming figure. She wanted revenge for

the death of her family. Somehow she’d

managed to learn how to fight with a broadsword. That was all I knew. Who had trained her? Why?

What pushed her to seek a bloody vengeance? What was going to happen to her after she got

it?

The ultimate

answer: like most cardboard, she tore apart.

Pieces of her life appear in the Deverry sequence, but she herself is

gone, too shallow to live. But her

passing spawned a great many other characters, both female and male.

Her actions had only the most minimal

consequence. She killed the murderer --

consequences for him, sure -- but he was a nobleman. What would his death mean to his family? His land holdings? The political hierarchy of which he was a

part? Come to think of it, what was the

political hierarchy in his corner of the fantasy world? Everyone had Celtic names. Their political world would not be a standard

English-French feudal society. People

still worshipped the pagan gods, too.

Why weren’t they Christianized?

The ultimate answer: they weren’t

in Europe. They’d gone elsewhere. A very large elsewhere, as it turned

out. And then of course, I had to ask:

how did they get there?

Now, some people, more sensible

than I am, would have sat down with a couple of notebooks and rationally figured

out the answers to all these questions.

They would have taken their decisions, possibly based on research, back

to the original novella and revised and rewrote until they had a nice short

novel. Those of us addicted to sagas,

however, are not sensible people.

Instead of notes and charts, I wrote more fiction.

Here’s

where the subconsious mind comes in.

Each question a writer asks herself can be answered in two different

ways, with a dry, rational note, or a chunk of story. When she goes for the story option, the saga

takes over. To continue my novella

example, I wrote the scene where the dead lord’s body comes back to his castle,

which promptly told me it was a dun, not a castle, thereby filling in a bit more

of the background. In the scene of mourning

other noble lords were already plotting to get hold of his land, maybe by

appealling to an overlord, maybe by marrying off his widow to a younger

son. The story possibilities in that

were too good to ignore.

You can see their ultimate

expression in Books Three and Four of the Deverry saga with It just

took me a while to get there. The woman

warrior, complete with motivation and several past lives’ worth of history, appears in the saga as Jill, Cullyn

of Cerrmor’s daughter, but she is not the same person as that first piece of

cardboard, not at all. The opening of

the original novella, when a woman dressed as a boy sees a pair of silver

daggers eating in an innyard, does appear in a different context with different

characters in Book Six, when Carra meets Rhodry and Yraen. Rather than revenge, however, she’s seeking

the father of her unborn child.

the hassle over the

re-assignment of Dun Bruddlyn.

More story

brings more questions. The writer’s

mind works on story, not “information”.

Pieces of information can act as the gateways that open into stories and

lead the writer into a saga. Tolkien

started his vast saga by noticing some odd discrepancies in the vocabulary of

Old Norse. Sounds dull, doesn’t it? But he made something exciting out of

it. The difference between varg

and ulf was just a gate, an innocent little opening leading to a vast

life’s work.

Not every

writer works in the same way, of course.

Many writers make an outline, draw up character sheets, plan the

structure of the book to be, and then stick to their original decisions. Often they turn out good books that way,

too. I don’t understand how, but they

do. I personally am a “discovery

writer”, as we’re termed, someone who plans the book by writing it and then

revising the entire thing. When it comes

to saga, this means writing large chunks of prose before any of it coalesces

into a book. I never finished any of the

first drafts of these chunks. Later I

did, when I was fitting them into the overall series.

(Someone like

Tolkien, who had a family and a day job, may never get to finish all of his

early explorations of the material. Such

is one risk of saga. Readers who

criticize him and his heirs for all those “unfinished tales” need to understand

where the tales came from. Anything

beyond a mere jotting belongs to the saga.)

Another

risk: the writer can put a lot of energy into a character or tale only to see

that it doesn’t belong and must be scrapped.

When I was trying to turn the original ghastly novella into DAGGERSPELL,

the first Deverry novel, the most important dweomerman was an apothecary named

Liddyn, a nice fellow, not real interesting though. My subconscious created a friend of his, a

very minor character, who appeared in one small scene, digging herbs by the

side of the road. When the friend

insisted on turning up in a later scene, I named him Nevyn. If I’d stuck to my original plan, that would

have been it for Nevyn. As soon as I

asked myself, “but who is this guy?” I realized what he was bringing with him:

the entire theme of past lives. Until

that moment, reincarnation had nothing to do with this saga.

Liddyn

shrank to one mention in one of the later books. Nevyn took over.

The past lives appeared when I

asked myself how this new strange character got to be a four hundred year old

master of magic. What was his

motivation? How and why did he study

dweomer? These questions brings us right

back to the idea of consequences. As a

young man Nevyn made a bad mistake out of simple arrogance. The consequences were dire for the woman who

loved him and her clan, and over the years these consequences spiralled out of

control until they led ultimately to a civil war. The saga had gotten longer but deeper, and I

hope richer. Had I ignored these

consequences, I would have been left with an interesting episode, isolated, a

little thin, perhaps at best backstory.

The term

“backstory” always implies a “frontstory”, of course, the main action, the most

important part of a book. Some readers

get impatient if they feel there’s too much of this mysterious substance,

backstory, in a given book or movie.

They want to know what they’re getting, where the story is going, and in

particular, what kind of story it is, front and center. Sagas, however, can’t be divided into back

and front. Is the Trojan War less

important than Odysseus’s wanderings?

The one is not “backstory” to the other.

The saga

has much in common with the literary form critics call the “roman fleuve,” the

river-system novel. A great many stories

flow together in one of these, like the tributaries that together make up a

mighty river meandering across a plain.

The classic example is Balzac’s Comedie Humaine. Romans fleuve follow a wide cast of

characters over a stretch of time, just as true sagas do. None of the stories are less important than

any other.

The past and present of the created

world together produce the last essential element of a saga: the feeling of

change, of movement forward in time of the saga’s world. In a true saga something always passes away,

but at the same time, something new arrives.

The elves leave Middle Earth, but the Fourth Age begins. True sagas, in short, include a future.

And that

future often calls the writer back to the saga.

Sometimes the damn things won’t leave us alone. Which is why I find myself contemplating a

return to Deverry for a novel that takes place hundreds of years after the main

saga. It should be a stand-alone, I

think. But I’m not betting on that.

Published on October 04, 2013 01:00

October 3, 2013

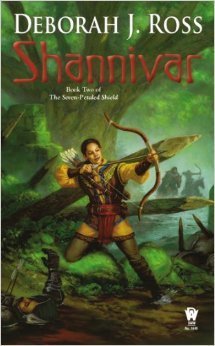

SHANNIVAR cover!

Here's the cover for Shannivar, the second book of The Seven-Petaled Shield. I am so pleased with the artwork by Matt Stawicki! It's available for pre-order at the usual places, for an early December release.

Published on October 03, 2013 16:26

October 2, 2013

Evil, the Fantastic, and Making Sense Out of Pain

After a brief hiatus, I've returned to the Great Traveling Fantasy Round Table. This month's topic, hosted by Warren Rochelle, is "Evil and the Fantastic." My entry is below, but please go read the others. And write your own!

***

I don’t think it’s possible to discuss evil without talking

about the literature of the fantastic. We hear people talk about “evil

incarnate,” usually in reference to some person or institution that has committed

particularly heinous acts, as if evil were a tangible, measurable thing that

exists outside the human imagination. In real life, things are rarely that

simplistic.

Certainly, history and even some current religious thought puts

forth the notion of those, human or not, who are inherently evil. To this day,

some people believe that snakes (or spiders or other animals) are evil (I

encountered one such man in a pet store, warning his young son that the garter

snake would steal his soul if he weren’t careful). Once the mentally ill (or

physically ill, such as those who suffer from epilepsy) were thought to be

possessed by demons. Such beliefs persist today on the fringes of mainstream

Western society, although they have largely been expunged from medical and

psychiatric practice. We believe that such conditions as schizophrenia and

sociopathy arise from disorders of neurophysiology, even if we cannot yet

pinpoint the precise etiology. Even when we do know exactly what

neurotransmitters and part of the brain are involved, it is still a widespread

and understandable human tendency to ascribe unexplained phenomena, whether

beneficial or destructive, to supernatural agency. Even though intellectually

we may understand that a mass murderer is not an incarnation of some demonic

spirit, nor is he possessed by one, and even if we cannot explain why such a

person is utterly lacking in empathy for other human beings, we still often use

words like evil, wicked, damned,

devilish, satanic, and demonic.

Humans are capable of cruelty and viciousness so extreme in

degree or scope that few of us can comprehend it, let alone the motivation

behind it. How can we make sense of atrocities like the Holocaust or its

equivalents, historical or modern? Of the massacres in Africa, Central Europe,

the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, to name but a few?

I think we can’t, not by ordinary thought. The mind numbs

with the magnitude of such

deliberately inflicted suffering and takes refuge in

numbers, pop psychology, and political analysis. It is difficult enough to

struggle with the petty unkindnesses of everyday life, the irritations, the

mundane acts of thoughtlessness, the emotions like jealousy or vindictiveness.

Almost everyone loses their temper with one another at one time or another, or

an unhealed resentment prompts them to strike out without thinking. These acts

are understandable even when we disapprove of them, because they lie within the

scope of our own experience. As we seek forgiveness for ourselves, we find the means

to extend it to others. While these moments, and the means of making and

accepting amends, smooth our relationships, they don’t make for a very dramatic

tale.

Fantastical literature, on the other hand, enlarges the

sphere of reality. This could be the introduction of magical elements into the

ordinary world (urban fantasy), or parallel worlds (such as Faerie or Narnia)

that interact with our own, each with its own set of rules. Or completely

independent worlds (Discworld, Middle Earth).

Fantastical literature is also characterized by the use of

archetype and metaphor to evoke experiences for which we have no direct

vocabulary. We don’t need to have personally surrendered to the Dark Side of

the Force in order to understand why the temptation is at once seductive and

terrifying. Nor do we need to have witnessed an atomic bomb blast to imagine

the devastation of dragonfire or a wrathful volcano god/dess.

In discussing how to portray interesting, multi-dimensional

villains, it’s often pointed out that these characters – antagonists to the

point of view character – are often heroes in their own eyes. They don’t get up

in the morning, look in the mirror, and say, “I’m going to be evil today” or

“Evil! Evil! Rah-rah-rah!” The best and most frightening villains have the same

capacity for greatness as do heroes, whether it is physical prowess, intellect,

a wounded heart, or simple charisma, only it is applied either in the wrong

manner or for the wrong ends. If a tragic hero has a fatal flaw but is

nonetheless admirable, then a great villain also has his blind spots, to his

ultimate ruin.

Evil in fantastical literature ranges from the motivating

force in such otherwise sympathetic villains to a “pure” black-and-white

quality, one that is so alien to ordinary human sensibilities as to be utterly

incomprehensible. We cannot know what it is, but we can know its effects – what

it does to individuals, nations, and entire worlds. Black-and-white evil is in

most instances a whole lot less interesting than those who come under its influence

but still retain some degree of choice. That choice may be a once-and-for-all

decision, informed or otherwise, or it can be the continuing possibility of

turning away from the inevitable consequences, a possibility that diminishes

with each step toward the abyss.

If Evil is monolithic, unmixed with any goodness, and

incapable of change, then the resolution of the story conflict is reduced to

either/or, yes/no, win/lose. This is not to say that such tales are less adrenaline-fueled

than those that are more complex, only that there are fewer possibilities for a

denouement: Evil wins and everyone dies/suffers; Good wins and the hero lives

happily ever after; Good wins but the hero meets a tragic, sacrificial end. The

first two may lead to an exciting climax and catharsis but are unlikely to

offer the deeper emotional resonance of the third. If, on the other hand, Evil

is one among many conflicting motivations, other resolutions become possible.

The evil character discovers the capacity for love and sacrifices himself for a

greater cause; the hero and villain form an alliance; either hero or villain

crosses the gulf between them and healing ensues; the villain makes a

last-ditch effort to salvage some good from the harm he has done; the

possibilities become endless. All these rely on the capacity of sentient beings

to choose their future actions, even when they had no power over what happened

to them in the past and cannot undo what they have done. And in the course of

these journeys, we ourselves gain insight into our own unhealed wounds, our

festering resentments, our self-condemnation, and ultimately, our hope for

redemption.

***

P.S. If you enjoy my blog writing, I hope you'll check out my fiction.

***

Devil sign, photo by Miraceli, Licensed under Creative Commons.

"To The Accuser" is by William Blake, in public domain.

***

I don’t think it’s possible to discuss evil without talking

about the literature of the fantastic. We hear people talk about “evil

incarnate,” usually in reference to some person or institution that has committed

particularly heinous acts, as if evil were a tangible, measurable thing that

exists outside the human imagination. In real life, things are rarely that

simplistic.

Certainly, history and even some current religious thought puts

forth the notion of those, human or not, who are inherently evil. To this day,

some people believe that snakes (or spiders or other animals) are evil (I

encountered one such man in a pet store, warning his young son that the garter

snake would steal his soul if he weren’t careful). Once the mentally ill (or

physically ill, such as those who suffer from epilepsy) were thought to be

possessed by demons. Such beliefs persist today on the fringes of mainstream

Western society, although they have largely been expunged from medical and

psychiatric practice. We believe that such conditions as schizophrenia and

sociopathy arise from disorders of neurophysiology, even if we cannot yet

pinpoint the precise etiology. Even when we do know exactly what

neurotransmitters and part of the brain are involved, it is still a widespread

and understandable human tendency to ascribe unexplained phenomena, whether

beneficial or destructive, to supernatural agency. Even though intellectually

we may understand that a mass murderer is not an incarnation of some demonic

spirit, nor is he possessed by one, and even if we cannot explain why such a

person is utterly lacking in empathy for other human beings, we still often use

words like evil, wicked, damned,

devilish, satanic, and demonic.

Humans are capable of cruelty and viciousness so extreme in

degree or scope that few of us can comprehend it, let alone the motivation

behind it. How can we make sense of atrocities like the Holocaust or its

equivalents, historical or modern? Of the massacres in Africa, Central Europe,

the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, to name but a few?

I think we can’t, not by ordinary thought. The mind numbs

with the magnitude of such

deliberately inflicted suffering and takes refuge in

numbers, pop psychology, and political analysis. It is difficult enough to

struggle with the petty unkindnesses of everyday life, the irritations, the

mundane acts of thoughtlessness, the emotions like jealousy or vindictiveness.

Almost everyone loses their temper with one another at one time or another, or

an unhealed resentment prompts them to strike out without thinking. These acts

are understandable even when we disapprove of them, because they lie within the

scope of our own experience. As we seek forgiveness for ourselves, we find the means

to extend it to others. While these moments, and the means of making and

accepting amends, smooth our relationships, they don’t make for a very dramatic

tale.

Fantastical literature, on the other hand, enlarges the

sphere of reality. This could be the introduction of magical elements into the

ordinary world (urban fantasy), or parallel worlds (such as Faerie or Narnia)

that interact with our own, each with its own set of rules. Or completely

independent worlds (Discworld, Middle Earth).

Fantastical literature is also characterized by the use of

archetype and metaphor to evoke experiences for which we have no direct

vocabulary. We don’t need to have personally surrendered to the Dark Side of

the Force in order to understand why the temptation is at once seductive and

terrifying. Nor do we need to have witnessed an atomic bomb blast to imagine

the devastation of dragonfire or a wrathful volcano god/dess.

In discussing how to portray interesting, multi-dimensional

villains, it’s often pointed out that these characters – antagonists to the

point of view character – are often heroes in their own eyes. They don’t get up

in the morning, look in the mirror, and say, “I’m going to be evil today” or

“Evil! Evil! Rah-rah-rah!” The best and most frightening villains have the same

capacity for greatness as do heroes, whether it is physical prowess, intellect,

a wounded heart, or simple charisma, only it is applied either in the wrong

manner or for the wrong ends. If a tragic hero has a fatal flaw but is

nonetheless admirable, then a great villain also has his blind spots, to his

ultimate ruin.

Evil in fantastical literature ranges from the motivating

force in such otherwise sympathetic villains to a “pure” black-and-white

quality, one that is so alien to ordinary human sensibilities as to be utterly

incomprehensible. We cannot know what it is, but we can know its effects – what

it does to individuals, nations, and entire worlds. Black-and-white evil is in

most instances a whole lot less interesting than those who come under its influence

but still retain some degree of choice. That choice may be a once-and-for-all

decision, informed or otherwise, or it can be the continuing possibility of

turning away from the inevitable consequences, a possibility that diminishes

with each step toward the abyss.

If Evil is monolithic, unmixed with any goodness, and

incapable of change, then the resolution of the story conflict is reduced to

either/or, yes/no, win/lose. This is not to say that such tales are less adrenaline-fueled

than those that are more complex, only that there are fewer possibilities for a

denouement: Evil wins and everyone dies/suffers; Good wins and the hero lives

happily ever after; Good wins but the hero meets a tragic, sacrificial end. The

first two may lead to an exciting climax and catharsis but are unlikely to

offer the deeper emotional resonance of the third. If, on the other hand, Evil

is one among many conflicting motivations, other resolutions become possible.

The evil character discovers the capacity for love and sacrifices himself for a

greater cause; the hero and villain form an alliance; either hero or villain

crosses the gulf between them and healing ensues; the villain makes a

last-ditch effort to salvage some good from the harm he has done; the

possibilities become endless. All these rely on the capacity of sentient beings

to choose their future actions, even when they had no power over what happened

to them in the past and cannot undo what they have done. And in the course of

these journeys, we ourselves gain insight into our own unhealed wounds, our

festering resentments, our self-condemnation, and ultimately, our hope for

redemption.

***

P.S. If you enjoy my blog writing, I hope you'll check out my fiction.

***

Devil sign, photo by Miraceli, Licensed under Creative Commons.

"To The Accuser" is by William Blake, in public domain.

Published on October 02, 2013 01:00