Deborah J. Ross's Blog, page 132

April 18, 2014

GUEST BLOG: Dave Trowbridge on Rehabilitating Our "New" Old Dog

One of the joys of having a dog-savvy partner is being able to compare notes, especially when faced with a challenged dog. Here are some insights from my husband.

One of the joys of having a dog-savvy partner is being able to compare notes, especially when faced with a challenged dog. Here are some insights from my husband.When we began looking into ways to rehabilitate Tajji, at least one source noted a tendency for a dog to backslide for “three to seven days” in the relatively complex training required. Two weeks ago we noted something like this in a rebound in Tajji’s reactivity to other dogs, culminating a couple of days ago in her “going off” at an empty yard where she frequently sees a reactive GSD, then nowhere in evidence. About a week ago she added barking at pedestrians at some distance. Despite the warning, her regression was a bit disheartening after the more rapid progress of the previous five weeks.

Enlightenment followed last Tuesday, in conversation with one of Tajji’s former owners. Deborah and I had misunderstood the order of events, believing that Tajji’s disorderly behavior was the result of not knowing how to behave outside a service harness. Instead, it turns out that the barking and lunging had developed while she was working. Of course, her blind person had little or no warning, and it got so bad that people were crossing the street to avoid her. Her owners worked with more than one professional trainer, but nothing helped, and so she was retired.

In short, she had a nervous breakdown.

Putting this discovery together with what we’ve been learning about reactive dogs and our observations of Tajji’s nature, we’ve come up with a hypothesis that goes something like this:

German Shepherd Dogs are the epitome of what Grisha Stewart calls “information dogs,” dogs that really need to know everything that’s going on. Tajji is a specialized sub-breed of GSD in which this highly developed awareness has been further honed and coupled with excellent vision. The result is a kind of hyper-vigilance, which is what’s needed for the demanding task of maneuvering a blind person through a first-world environment.

At the same time, her training, although entirely positive, was, in the words of Tajji’s sighted co-owner, “the most unnatural thing you can imagine for a dog.” This training takes a highly-social pack animal with a rich real-time postural and positional “language” combined with one of the best noses on the planet, and either re-channels or suppresses all of the behaviors natural to such an animal to the end of enabling independence for the blind. (On a side note, this makes it all the more impressive that almost two-thirds of Fidelco-bred dogs graduate as seeing eye dogs—testimony to both good breeding and good training.)

Now add the fact that dogs are natural mind-readers with an inherited understanding of human body language, yet working with the blind means the dog’s main human can only “hear” a fraction of what the dog says. So the relationship is fundamentally one in which the human is “speaking” clearly, even loudly, but not hearing at all well, and often misunderstanding even what it hears. I think most of us have been in similar situations for at least short periods of time, and know how frustrating and exhausting it can be.

Now imagine what it’s like doing that most of your waking hours—and far more of them than you’re used to—for almost eight years. That’s the life of a seeing eye dog. Tajji would have had to retire soon anyway just because of her age and the physical demands of the job, so neither she, Fidelco, or her owners have failed in any real sense.

There’s of course no way to know why she broke down when she did, but we think there may have been some contributing factors here specific to Tajji’s situation. Her signals are very subtle, so subtle that even with our experience we were missing some of them. You might say that she whispers much of the time. Yet she has no hesitation in telling you what she wants, to the point of what might be called stubbornness. We’ve no doubt she was signaling her increasing distress at whatever was happening with her for some time, but even had her sighted co-owner been more of a dog-speaker, those signals could easily have been overlooked for some time.

Part of that distress could have been due to a broken carnassial tooth (the big shearing ones): a slab fracture that left a fingernail-sized chip of enamel pivoting in the gum. This happened in 2011, and there’s a great deal of tartar built up and some evident sensitivity. For instance, when she plays tug, she will try a “catch bite” (opening the mouth while lunging to get a better grip on something) and then let go immediately. I can only imagine what working for a shouting deaf person while dealing with a toothache would be like. That will be taken care of next week.

In the meantime, Tajji surprised me today with a flawless walk around the block, encountering a jogger, two pedestrians, two cars being parked with people emerging, a truck driver making a delivery, and the dreaded empty GSD yard [where a German Shepherd who usually barks and lunges at the fence, setting Tajji off] with only the slightest arousal at any given point, quick relaxation and orientation on me, and the self-chosen execution of several different calming behaviors (eg, sniffing). Part of this may be the natural up-and-down of training, and part of it may be how we’re adjusting our approach. Deborah will talk about that next week.

Published on April 18, 2014 17:27

April 16, 2014

[link] Bonnie talks about tango dancing and cancer

Here's a link to a short clip from the video the Smart Patients folks made of Bonnie. She'd gone tango dancing, oxygen tank and all. I hand in her favorite pair of shoes, red satin. The 7 1/2 cm heels are also the size of the largest of her lung tumors at the time she went into hospice. Damn, I miss that woman.

http://vimeo.com/75934182

http://vimeo.com/75934182

Published on April 16, 2014 17:03

April 14, 2014

Blog Hop: What I'm Working On Now

Mary Rosenblum passed on this blog meme to me. Check out her answers, too.

Mary Rosenblum passed on this blog meme to me. Check out her answers, too.What am I working on? I’m working on two novels, drafting one and revising another. The first is for a project I can’t announce yet (stay tuned!) but I am enjoying the special delight of beginning a new novel. I began the second about a year ago, purely for my own pleasure, and it provided a precious personal sanctuary while I was taking care of a dying friend. Its working title is Penumbra, and here’s the skinny:

What happens when a science geek falls in love with a vampire? High school senior Esther Goldberg has smarts and a no-nonsense approach to life, a lesbian science geek determined to pursue her dream career as an astronomer. Esther’s family – her widowed, overworked mother, phonograph-playing aunt, and her great-uncle, a gentle soul still wounded from surviving a concentration camp – doesn’t have a lot of money, but they do have a lot of love, even when they don’t entirely understand her. When a mysterious and beautiful girl joins Esther’s AP Physics, the entire class falls for her, Esther included. Messages in Marielle’s handwriting appear in Esther’s notebook and as quickly disappear, and Marielle herself utters cryptic references to “we are both creatures of the night.” That’s only the beginning of Esther’s adventure...

It’s so interesting to move back and forth between stories in such different places in the creative process. In my editing work, I’m putting together a series of author interviews for Stars of Darkover and preparing to edit the next Darkover anthology, Gifts of Darkover (2015).

How does my work differ from others of its genre? I’m not sure that it does; there are so many talented and accomplished writers in the field of fantasy and science fiction, some of them with imaginations so wild, I feel downright conventional and definitely in distinguished company. However, if I were to look at the recurring themes, the “hallmarks” of my work, they would include heroes with compassion and brains, the many ways we heal individually and in community, very cool animals, very cool love stories, and a deep sense of romanticism.

Why do I write what I do? I write fantasy and science fiction because I love to read it. I get to make my living by indulging in my not-so- guilty pleasures. A distant second reason is that this is an amazing community, contentious and loving and sometimes life-saving.

How does your writing process work? I sort through the packets the Idea Fairy has left under my pillow, looking for the shiniest. Of those, I pick a few with potential to actually become stories. Sometimes, I have to shuffle them around and mix-and-match. Eventually I reach an ignition point… Okay, seriously: Right now in my career, with the exception of the on-spec novel I mentioned above, I sell on contract, which means I hand my agent a detailed outline (and sometimes sample chapters) and when we have a contract and advance in hand, I get to work. I more or less follow the outline, drafting quickly – 1200 to 2500 words a day, six days a week. Then I print the mess out, attack it with a red pen, rinse and repeat. At some point, it goes to a trusted reader, rinse and repeat, and then to my agent. At some point, I gird myself up to cope with editorial revisions, reviewing copy edits, and proofreading. I love revising a book because I see patterns and connections I had no idea were there. It’s like discovering a new solar system in your garden.

The drawing is by Ernst Keil, 1871.

Published on April 14, 2014 01:00

April 11, 2014

How To Be A Dog: Walkies

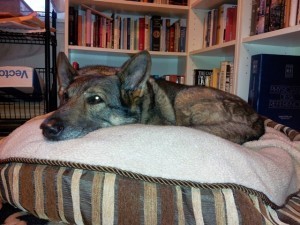

Hanging out When she came to live with us, our retired seeing eye dog, Tajji, had on on/off switch. “On” meant working on a rigid guide harness, focusing on all the things she had been taught to do for her blind handler, to the exclusion of all else. Guide work is enormously demanding for the dog, both physically and mentally. The dog must learn many behaviors (such as looking both ways when passing through a door or stepping off a curb into a street) and must perform them reliably. In addition, she must be strong enough to physically pull her person out of harm’s way. “Off” meant “no holds barred, completely off duty.” According to her former owner, this included pulling hard on the leash, playing “keep away,” jumping up on people, and barking and lunging at other dogs. We very soon witnessed all of these behaviors, all of them unacceptable in a companion animal. Now Tajji must learn a new set of behaviors: “normal manners.”

Hanging out When she came to live with us, our retired seeing eye dog, Tajji, had on on/off switch. “On” meant working on a rigid guide harness, focusing on all the things she had been taught to do for her blind handler, to the exclusion of all else. Guide work is enormously demanding for the dog, both physically and mentally. The dog must learn many behaviors (such as looking both ways when passing through a door or stepping off a curb into a street) and must perform them reliably. In addition, she must be strong enough to physically pull her person out of harm’s way. “Off” meant “no holds barred, completely off duty.” According to her former owner, this included pulling hard on the leash, playing “keep away,” jumping up on people, and barking and lunging at other dogs. We very soon witnessed all of these behaviors, all of them unacceptable in a companion animal. Now Tajji must learn a new set of behaviors: “normal manners.”One of life’s joys is taking your dog for a walk. It’s not only good exercise, it’s a conversation between you. Even if you’re walking and talking with a human friend, you and the dog can be in communication. When we looked at Tajji’s challenges, we saw several distinct behaviors to work on.

Walking on a loose leash, both beside the human handler and at a distance, depending on the length of the leash. Enjoying the banquet of smells, but coming back to heel readily when called.“Checking in” with the handler.Walking calmly past other dogs and humans; approaching them only when released to do so. Greeting humans in a calm way.

Dog-reactivity is a big chunk, so we’re working on that separately. First, we needed to get Tajji solid with the first three skills. She already had the foundational skills of Sit, Stay (Wait), and Down, although her Heel and Come are not reliable when she’s in full-blown “off” mode, so they’ll need more work.

To help Tajji learn not to pull, we decided to never attach a leash to her flat leather collar. Previously, that’s the setup in which she pulled strongly, so we don’t want to replicate those conditions. Dogs have a reflex to push against any pressure on neck or chest, so a flat collar (or even a choke chain, which we do not use on our dogs) gives them that signal. Instead, we chose a front-clip harness. This is a soft nylon webbing harness, so it’s not like the rigid leather guide harness, and it has a clip in the center of the chest strap. When the dog pulls, she is turned toward the side of the leash. This often breaks her focus on whatever it is she is moving toward, as well as restraining her in a humane way.

Go Sniff

Go Sniff

Coming back to HeelTajji quickly adapted to the harness, which stopped almost all of the pulling (except in the presence of other dogs). We then used clicker-training to reward walking close to us or coming back to Heel when called. Because we live in a semi-rural setting and there are so many wonderful things to smell (traces of other dogs, wild animals), we don’t want to keep her in strict Heel position all the time – we want her to have fun on the walks! At first, she was hesitant to leave the side of her handler, undoubtedly a holdover from her previous work training and having lived in an apartment in a small city. So we encouraged her to Go Sniff. This skill has the added advantage that sniffing the ground is a calming behavior for dogs and we’ll be able to use it as a relaxation technique when we work on Tajji’s dog reactivity.

Coming back to HeelTajji quickly adapted to the harness, which stopped almost all of the pulling (except in the presence of other dogs). We then used clicker-training to reward walking close to us or coming back to Heel when called. Because we live in a semi-rural setting and there are so many wonderful things to smell (traces of other dogs, wild animals), we don’t want to keep her in strict Heel position all the time – we want her to have fun on the walks! At first, she was hesitant to leave the side of her handler, undoubtedly a holdover from her previous work training and having lived in an apartment in a small city. So we encouraged her to Go Sniff. This skill has the added advantage that sniffing the ground is a calming behavior for dogs and we’ll be able to use it as a relaxation technique when we work on Tajji’s dog reactivity. Practicing Look

Practicing Look

Check In, loose leashChecking in is a variation on Look, one of the things we teach all our dogs. It’s a way of asking the dog to pay attention to us. Eye contact isn’t natural for dogs, the way it is for people, so we practiced it with the clicker and treats indoors, where there are fewer distractions. Once she learned the command Look, we were able to practice it outside (click/treat) and then to click/treat when the behavior is offered without the command. All the while telling her what a good job she’s doing, of course.

Check In, loose leashChecking in is a variation on Look, one of the things we teach all our dogs. It’s a way of asking the dog to pay attention to us. Eye contact isn’t natural for dogs, the way it is for people, so we practiced it with the clicker and treats indoors, where there are fewer distractions. Once she learned the command Look, we were able to practice it outside (click/treat) and then to click/treat when the behavior is offered without the command. All the while telling her what a good job she’s doing, of course.Now we have the foundations for a pleasant walk with a dog who keeps in touch with us while “enjoying the scenery” within the length of the leash.

Published on April 11, 2014 01:00

April 9, 2014

Proofreading The Catch Trap

Book View Café is a publishing cooperative, both in the business and the friendly sense of the word. We offer one another all the services a traditional publisher would normally provide, everything from editing a previously-unpublished work to formatting and cover design, as well as the technical skills necessary to operate the bookstore and website. Not all of us have such specialized knowledge, but just about all of us can proofread a manuscript for another editor.

Book View Café is a publishing cooperative, both in the business and the friendly sense of the word. We offer one another all the services a traditional publisher would normally provide, everything from editing a previously-unpublished work to formatting and cover design, as well as the technical skills necessary to operate the bookstore and website. Not all of us have such specialized knowledge, but just about all of us can proofread a manuscript for another editor.I recently “carried my fair share” by proofreading the BVC ebook edition of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s novel, The Catch Trap. (Actually, I was one of two proofreaders, so you can pick which one of us to blame for any typos you find!) The Catch Trap one of those richly layered books that is “about” a lot of different things. It’s a gay love story, sure, but it’s also about life in a traveling circus at the twilight of that life, and it’s about all the ways families destroy and save us. It’s about that rare bond of a shared vocation, a calling, the thing that makes us most fully alive. Not just sex, but flying, and more about that later.

One recommended study techniques for newer writers is to type out a paragraph, a page, a chapter by a favorite author. Putting the words down on paper helps you to perceive and understand what the writer did, how he put together that scene. Proofreading and copy-editing are a little like that because of the attention to detail – grammar, spelling, punctuation, incorrect word choice. In this case, the file was from a scan of a print edition, and the OCR software had added some odd glitches. I also had to read for homonyms and typos that are still words, things a spell-checker wouldn’t catch. That meant I had to pay attention not just to punctuation and oddly placed spaces, but to the sense of the sentence. This required a different sort of attention than ordinary pleasure reading or even editorial reading. The combination put me “inside” the story, as if I were looking over Marion’s shoulder as she constructed it. I say “constructed” because proofreading it was in some ways like moving, slowly and carefully, through a hologram that contained not only three-dimensional blueprints, but all the finishing touches.

When I first read The Catch Trap several decades ago, I had no expectations beyond that it was a novel by Marion Zimmer Bradley. I was only mildly curious about circus life. The story greeted me where I was and led me into a world I knew very little about, feeding me what I needed to know to appreciate what was going on. There was a lot of information to transmit: not only the characters but their family connections, the various jobs and training required, the color and atmosphere of a traveling circus in the mid 1940s and all the ways in which it was a life apart. On the first page, I met Tommy Zane, a kid from a lion-tamer family, and on the second page, I watched Tommy and Mario Santelli, a brilliant trapeze flyer, begin their friendship. The third page told me of Tommy’s longing to not follow in his father’s footsteps as a “cat man”, but to soar on the trapeze, which Mario then begins teaching him. So in the space of the very beginning of the first chapter, Bradley set up the entire 600 page novel. There was no “shooting the sheriff on the first page,” nor huge chunk of bewildering exposition, nor wandering characters who have nothing to do with the central plot. Bradley told me up front what the story was going to be: two men, their families, circus life, and most of all, their shared passion for trapeze work.

Tommy’s admiration for Mario becomes interwoven with his adolescent sexual awakening. The story could have unfolded without the sexual relationship, with all the plot points being roughly the same. I can’t speculate why Bradley chose to weave in a gay love story when an intense working friendship might have sufficed; I can only look at the result. The Catch Trap was first published in 1979, hardly the heyday of tolerance, and the story takes place from 1944 to 1953, when there were very few places where open homosexuality did not carry significant risk, often deadly. While I image that many readers in 1979 reacted to the gay element for one reason or another, it seemed to me as I proofread the book that it was only one of many interwoven themes. Bradley used it to contrast and highlight the many repeated instances of alienation, privacy, and secrets – between the circus and the mundane world, between various traditions and circuses, between and within families. She uses the word “passion” to mean not only sexual desire but fervor and longing for a rare and fleeting experience – flying through the air in perfect timing and harmony with another person. Tommy and Mario hold each other’s lives in their hands, not just in terms of how dangerous it was to be gay at that time, and not just how deeply each could wound the other, but their very lives.

In the end, as in the beginning, the story is not about sex, it’s about a shared dream:

"Flying is supposed to look like one of those flight dreams, so simple that people can’t believe they can’t do it themselves...Just pure, simple, perfect. So everybody watching will want to cry, because they know somewhere inside, in their guts, that they had wings and could fly once but they just forgot how.”

By the end of the book, I shared that dream, too.

Published on April 09, 2014 01:00

April 7, 2014

GUEST BLOG: Kari Sperring on Women and History

We ask a lot of history. It must tell us not simply of our varied pasts, but justify them to us, explain the present, excuse or support our weaknesses and desires, reflect for us those things about ourselves – our believed selves – that we admire or cling to or wish to make acceptable. We accuse it of lying or of incompleteness when – as it must do – it contradicts our deepest held understandings. We snatch at it, claw at it, paw over it to find the stories that make us feel safe and whole and good. It’s a lot to ask of anything, let alone a thing – a set of things – as fragile and oblique and compromised as this profession we call history. We make it our magic mirror, to show us who we want to think we are.

We ask a lot of history. It must tell us not simply of our varied pasts, but justify them to us, explain the present, excuse or support our weaknesses and desires, reflect for us those things about ourselves – our believed selves – that we admire or cling to or wish to make acceptable. We accuse it of lying or of incompleteness when – as it must do – it contradicts our deepest held understandings. We snatch at it, claw at it, paw over it to find the stories that make us feel safe and whole and good. It’s a lot to ask of anything, let alone a thing – a set of things – as fragile and oblique and compromised as this profession we call history. We make it our magic mirror, to show us who we want to think we are. As a woman and a writer and a historian, I’m asked to justify myself a lot. What point is there to history: it manufactures nothing tangible, critics say. It adds nothing to the GDP. What point is there to fiction? What point to any woman speaking out, anywhere, at any time? I have answers of a sort to all of these, differing according to my company. But they all come down to the same thing in the end: human beings seem to have a need to understand themselves as they are now, and they look back for help in this. Woman’s History Month seeks to highlight the hidden and forgotten histories of women, who, as a class, have been largely side-lined by the gatekeepers of the official past. Women’s history in general seeks to rediscover and document the lives and achievements of our female forebears of all times and identities. It’s a project I have a lot of sympathy with. And yet, and yet….

We ask such a lot of the past. As women – as female historians – it sometimes seems to me that we

ask even more of those women who preceded us than we ask of the past itself. Their lives become our voyages of discovery, their acts and desires are re-patterned and repurposed to fit modern needs and frameworks. As with the common complaint of women in a patriarchal culture – we have to be more than good enough, more than very good: we have to be better, best of all, to gain even the first step, the first rung, the first chance. Our female forebears must needs almost be superwomen, to justify their space in our narratives of history. It is not enough to have lived and worked. They must have been special, unusual, rare, even to get their names noted down in the sources on which historians depend. I have on my shelves a book on the histories of women, entitled Silences of the Middle Ages, a name which reflects the difficulty of finding much material at all about women for large periods of time. And yet, for all the slow increase of raw sources as we come closer to the present day, I sometimes think that all women’s history is the history of silence and of silencing. We are so easy to silence: many of us are taught to stay silent from our earliest days and can be reduced back to that state with a handful of sharp words. We are so easy not to hear or see or record, because of our social silence. A woman who speaks is mad or bad and, almost always, dangerous to know. There is a whole joyful industry of scholars and writers who rediscover and document such women now; those women who accidents of birth (usually) or marriage or situation or talent brought into the purview of the compilers of chronicles. Eleanor of Aquitaine, Wu Zetian, Hildegarde of Bingen, Lady Yohl Ik’nal, Hatshepsut, Börte, Makeda, Maria Sibylla Merian, Angelica Kauffman, Indira Gandhi. We celebrate and interrogate their lives in our search for ourselves, our meanings.

ask even more of those women who preceded us than we ask of the past itself. Their lives become our voyages of discovery, their acts and desires are re-patterned and repurposed to fit modern needs and frameworks. As with the common complaint of women in a patriarchal culture – we have to be more than good enough, more than very good: we have to be better, best of all, to gain even the first step, the first rung, the first chance. Our female forebears must needs almost be superwomen, to justify their space in our narratives of history. It is not enough to have lived and worked. They must have been special, unusual, rare, even to get their names noted down in the sources on which historians depend. I have on my shelves a book on the histories of women, entitled Silences of the Middle Ages, a name which reflects the difficulty of finding much material at all about women for large periods of time. And yet, for all the slow increase of raw sources as we come closer to the present day, I sometimes think that all women’s history is the history of silence and of silencing. We are so easy to silence: many of us are taught to stay silent from our earliest days and can be reduced back to that state with a handful of sharp words. We are so easy not to hear or see or record, because of our social silence. A woman who speaks is mad or bad and, almost always, dangerous to know. There is a whole joyful industry of scholars and writers who rediscover and document such women now; those women who accidents of birth (usually) or marriage or situation or talent brought into the purview of the compilers of chronicles. Eleanor of Aquitaine, Wu Zetian, Hildegarde of Bingen, Lady Yohl Ik’nal, Hatshepsut, Börte, Makeda, Maria Sibylla Merian, Angelica Kauffman, Indira Gandhi. We celebrate and interrogate their lives in our search for ourselves, our meanings.But we ask a lot of them. Not long ago, on a day devoted to celebrating women in science, I had a conversation about Annabella Milbanke, who even now, in our era of rediscovering women, is mostly remembered as a wife (to Byron) and a mother (to Ada, countess of Lovelace). Annabella was a highly talented mathematician, who as a teenager corresponded with adult men who were members of the Royal Academy, and was respected by them for her ability. Yet, if you glance at her biography on Wikipedia, say, what dominates our narrative of her is her piety and her strictness with her daughter. Biographers, over and over, accuse her of ‘not understanding’ her husband (her rapist and abuser) and of being cruel to her daughter. She was, certainly, not an easy woman. But why should she have been? She was a gifted women in an age when women were not permitted full access to a scientific life, nor considered possessed of full intelligence; she was a survivor of rape and violence. Byron was not a nice person, either. Yet his genius remains worthy of study, we are told, and hers does not. Annabella, across nearly 200 years, is not nice enough, sweet enough, silent enough, to deserve study and rediscovery by historians, male or female. Our female forebears, our re-found heroes, must be worthy by the standards imposed on us both by patriarchal culture and by ourselves. In seeking heroes, we still, it seems, seek to please the social standards that constrain us, and silence, ignore, or avoid those female forebears who make past and present standards uncomfortable. Some women, like Annabella, are too mean: they are the angry mad women in our collective attics. Others, (in)curiously, are too meek, too goody-goody to be worth noting (they don’t fit the check-list of modern ideas of agency). Blanche of Castille, Jane Seymour, Queen Tiye, Anne of Brittany: good wives and sisters and daughters, women who suffered and served. They make us uncomfortable, by fitting the social roles laid out for us too well. As male-dominated history judges us – not significant, not valuable, not important – so we judge other women from our collective pasts and consign them to continued silence. Women of the past must make us proud, and to do so, they must live up to our present-day needs. To justify ourselves, we need a history full of successes: we must answer the questions well – see our female Shakespeares (Lady Murasaki, Aphra Behn), our female politicians (Emma of Normandy, Matilda of Flanders, Wu Zetian), our musicians (Hildegarde, Fanny Mendlesohn) and artists (Frida Kahlo, Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun) and astronomers (Caroline Herschel). We don’t have space for the silent or those who failed for whatever reason to shine. We can’t afford them, though histories worldwide are full of undistinguished men. For women, even now, only the best will do.

Far more time and ink is expended in my field (Celtic- and Gaelic- speaking cultures of the British Isles c. 400 – c.1300) on the legal fiction of the banchomarbha(a land-holding woman with full social legal status, noted as a possibility in the highly schematising books of Irish laws, but who probably almost never happened in reality – no, not even in that highly imagined land ‘pre-Christian Ireland’, a place full of late 20th century wish-fulfilment fantasies and no reliable historical evidence for female agency at all)(1) than on the handful of real women whose names we know and about whose lives we possess fragmentary information. There’s part of me that understands that and sympathises. It’s hugely frustrating trying to reconstruct lives that are noted down so sparsely, and in terms of motherhood, marriage and renunciation. But these quiet women were real; they lived in those past worlds under those past rules for female conduct. And they deserve our attention as much as the women who broke or transcended those rules by being royal or rich or very, very lucky.

But they are very hard to find. Mostly, they have left us little or no trace at all. We can wonder, in museums or at archaeological sites, who owned and used that comb, that quern stone, those loom-weights? What did they talk about, the millions of everyday women whose names we don’t know? What were they like? There are, of course, also many millions of silent, forgotten, ordinary men. History – official histories – are classist as well as sexist and racist. The poor are not, in general recorded, and, when recorded, are noted mostly for crimes and accidents. But when we concentrate on Eleanor of Aquitaine and Wu Zetian, over Blanche of Castille and Xu Yihua, when we chase after fictional mediaeval Irish female lords rather than Gormflaith and Derforghaill, we are complicit in the silencing. We play the game by the rules imposed on us by social and cultural norms, that, where women are concerned, only the very best, the shiniest, the specialist snowflakes are worthy of attention and record and time.

We ask history to make us worthwhile, worthy of space and air and attention in our own lives. It’s a lot to ask. And perhaps we should be asking for something rather different. Not for a right to agency, or a justification for the claims we might make for agency, but rather, for something simpler. For recognition. We are here. We are real. We exist now and we existed then, and we are all of us worthy of attention and notice and record.

(1) I can supply a reading list on this. Please do not tell me about women from myths, legends, sagas or Roman period sources. They are not the same as real women in early Ireland. I’ve done years of detailed academic research in this field. This sounds brusque, I realise, but I’ve been having the ‘liberated Celtic women’ conversation with people for 25+ years, and it gets wearing.

Kari Sperring grew up dreaming of joining the musketeers and saving France, only to find they’d been disbanded in 1776. Disappointed, she became a historian and as Kari Maund published six books and many articles on Celtic and Viking history, plus one on the background to favourite novel, The Three Musketeers (with Phil Nanson). She started writing fantasy in her teens, inspired by Tolkien, Dumas and Mallory. She is the author of two novels, Living with Ghosts (DAW 2009), which won the 2010 Sydney J Bounds Award, was shortlisted for the William L Crawford Award and made the Tiptree Award Honours’ List; and The Grass King’s Concubine (DAW 2012).

Published on April 07, 2014 01:00

April 4, 2014

A gift from Hubble: Stars A-Bornin'

From the Hubble Space Telescope comes this glorious image of a star-forming region:

"clouds of gas and dust carved by winds and radiation from the region's newborn stars, now found scatteredin open star clusters embedded around the center of NGC 2174, off the top of the frame. Though star formation continues within these dusty cosmic clouds they will likely be dispersed by the energetic newborn stars within a few million years."

This takes my breath away, it's so amazing.

"clouds of gas and dust carved by winds and radiation from the region's newborn stars, now found scatteredin open star clusters embedded around the center of NGC 2174, off the top of the frame. Though star formation continues within these dusty cosmic clouds they will likely be dispersed by the energetic newborn stars within a few million years."

This takes my breath away, it's so amazing.

Published on April 04, 2014 11:30

April 2, 2014

[food] New Uses For Winter Squash

Tajji guarding squashI love winter squashes. They're delicious, versatile, and packed with nutrients. Some varieties you can find in markets pretty much all year round -- acorn and butternut, sometimes chunks of banana squash or Hubbard, with specialty or health food markets carrying kabocha and a few others, too. Others are seasonal. Pumpkins are easiest to find in the fall, and I think it's a tragedy that so many end up rotting when their decorative days are over. Delicata doesn't store well, so grab it while you can. Then there are the heirloom varieties, oh my. We've hardly begun our exploration of them.

Tajji guarding squashI love winter squashes. They're delicious, versatile, and packed with nutrients. Some varieties you can find in markets pretty much all year round -- acorn and butternut, sometimes chunks of banana squash or Hubbard, with specialty or health food markets carrying kabocha and a few others, too. Others are seasonal. Pumpkins are easiest to find in the fall, and I think it's a tragedy that so many end up rotting when their decorative days are over. Delicata doesn't store well, so grab it while you can. Then there are the heirloom varieties, oh my. We've hardly begun our exploration of them.Favorites so far: buttercup, carnival, blue Hubbard, Tennessee sweet potato squash (with a delicate but distinct sweet potato flavor); pumpkins like Cinderella or Musquee de Provence, small sugar pumpkins. Not so fond of tromboncini, but that could be that it's better as a tender summer squash.

This year, our garden produced about 200 lbs of winter squash. A large fraction of that was the Tennessee sweet potato squash, as the plants are as prolific as they are robust. Then we saw a stand of pumpkins that looked like Musqee de Provence and a similar, smaller white variety, at a local market. They were marked down to $1 each, although many of them weighed 15 lbs or more. I suspect they had been displayed for Halloween and never sold. We bought almost all of them and have been working our way through the enormous pile. The pumpkins had been roughly handled and set on concrete, so we had to scramble to use the damaged ones first. If the skins are intact and you wipe them down with dilute bleach to kill mold spores, they'll happily keep all winter.

There's only so much squash soup that you can eat, so I've been looking for other ways to use it. Our smaller squashes -- buttercup, butternut, etc. -- are delicious as a vegetable, baked and scooped out of the shell at the table. It turns out that diced winter squash goes beautifully in a variety of recipes, everything from lasagna and enchiladas to vegetable soup. Even oatmeal! Here are some additional discoveries:

Rice Cooker Polenta With Squash (4 servings)

1 c. polenta (coarse-ground corn meal)

3 c. water

1-2 c. diced (1/2" cubes) winter squash

1-2 tsp sugar if desired, depending on sweetness of squash

pinch of salt

Put everything in the rice cooker, stir and set on Normal. After about half an hour, stir again. For additional creaminess, let it sit on the Keep Warm setting for a couple of hours.

Pasta With Sausage and Squash (4 servings)

6 oz uncooked spirals or other pasta (we use Tinkyada Brown Rice Spirals since my husband doesn't tolerate wheat)

a little olive oil (1 -2 Tbsp)

2-4 sliced, cooked sausages of your choice (we like Aidell's smoked chicken varieties)

2 c thinly sliced winter squash (about 1/4" thick, 1 to 1 1/2" square or rectangle)

1 sliced red bell pepper

1 sliced onion (optional)

1/2 c. sliced celery (optional)

Cook the pasta according to directions. While it's cooking, warm the oil in a deep saucepan that has a lid. Saute the vegetables for a few minutes, then add some water or white wine, starting with 1/4 c, cover and let steam on low/medium heat. A few minutes before the pasta is done, dump in the sausages, stir, and cover. You should have enough liquid to make a sauce. Add the cooked pasta, toss, taste and add salt and/or pepper to taste. You can top it with grated Romano or Parmesan cheese.

Published on April 02, 2014 12:08

March 29, 2014

Living With Dogs: A Sense of Order

We used to joke that one of the jobs our old German Shepherd Dog, Oka, had taken upon himself,

Oka herding his ballwas to break up any disputes – real or imagined – between the cats. One of our cats tends to bully the others, pushing them out of their favorite sunbathing spots and persisting in playing “wrestle” when they very clearly are not interested. Both are usually accompanied by hisses and yowls and small furred bodies moving very quickly. Oka would immediately place his very considerable (90 lbs) bulk between them. We imagined him saying, “Break it up! Break it up! Move along now…”

Oka herding his ballwas to break up any disputes – real or imagined – between the cats. One of our cats tends to bully the others, pushing them out of their favorite sunbathing spots and persisting in playing “wrestle” when they very clearly are not interested. Both are usually accompanied by hisses and yowls and small furred bodies moving very quickly. Oka would immediately place his very considerable (90 lbs) bulk between them. We imagined him saying, “Break it up! Break it up! Move along now…”

Oka, like all dogs, had a very firm notion of what was good, orderly behavior and what was not to be allowed. Dogs are strongly oriented to routine, which is one of the things makes them so trainable. They make very specific associations (leash = walkies; vet’s office = horrible things happening to doggies; “Sit!” spoken in front of the refrigerator = sit in front of the refrigerator and no place else). We monkeys like to interpret this as our dogs having fixed ideas about the Way Things Should Be.

Oka’s Rules (as interpreted by his resident monkeys) included:

Cats shall not hiss at one another. Cats have razor blades on their feet and must not be closely approached.Deborah must be accompanied to and from the laundry area in the garage.The sole redeeming value of company is that the Evil Laser Bug comes out to play (therefore, Oka hung out in the living room, patiently watching the carpet for the first sign of the red dot.)The blue horse ball must be herded and barked at (see photo).Bodies of water deeper than a couple of inches are evil.Although of the same breed, Tajji has a different temperament and background. She’s only mildly interested in cat sparring and has shown no inclination to interfere. On the other hand, she has very strong opinions on her responsibility to keep an eye on her monkeys at all times. She’s willing to put up with one of us being behind a closed door if she can see the other. We found out very early that if only one of us was at home and if we closed but did not lock a door, for example a bathroom door, she would nose the door open. She can’t manage round door knobs, but she clearly knows how to push with paws and body weight. She will peek into the room and, having ascertained that the monkey within is not in distress, quietly withdraw. This has happened far too often to be an accident. We believe it was part of her training. So her list might read:

Monkeys must be monitored for well-being.A monkey behind a closed door must be checked on; a monkey that is unstable (I recently sprained an ankle) is clearly in need of assistance and requires a dog.Any monkey-not-of-family coming to the door must be barked at as loudly as possible.Cats are interesting and play fun games.Bodies of water deeper than a couple of inches must be jumped in with much happy splashing.In turns out that despite her excellent seeing eye dog training, Tajji lacks many of the skills of a family/companion dog, including the ability to walk calmly past other dogs, whether they are barking furiously from the sanctuary of their own fenced yards or on leashes on their own walks. When she’s excited, she’s not capable of responding to verbal commands or hand signals. She needs our help in learning to calm herself, and we’ve begun the process by building on her foundational clicker training (click = tasty treat, classical conditioning) with a relaxation protocol. This is a series of distraction tasks in which the dog is asked to sit quietly for increasing lengths of time while her monkey does various things: standing there, counting out loud, taking a few steps forward, backward, or sideways, clapping, jogging in place… At first, we practice in a quiet, familiar place, but as we go on, we’ll add distractions. Eventually we’ll enroll her in a “Reactive Rover” class where she’ll have graduated contacts with other dogs while remaining calm and focused on her monkeys. That should give us the basis for working with her on our neighborhood walks.

(One of the very cool things about these two pictures is you can see how similar in appearance the two dogs are. Oka was a large GSD at 90 lbs, and Tajji is about 65-70, but despite all their similarities, they are very different fur-people.)

Oka herding his ballwas to break up any disputes – real or imagined – between the cats. One of our cats tends to bully the others, pushing them out of their favorite sunbathing spots and persisting in playing “wrestle” when they very clearly are not interested. Both are usually accompanied by hisses and yowls and small furred bodies moving very quickly. Oka would immediately place his very considerable (90 lbs) bulk between them. We imagined him saying, “Break it up! Break it up! Move along now…”

Oka herding his ballwas to break up any disputes – real or imagined – between the cats. One of our cats tends to bully the others, pushing them out of their favorite sunbathing spots and persisting in playing “wrestle” when they very clearly are not interested. Both are usually accompanied by hisses and yowls and small furred bodies moving very quickly. Oka would immediately place his very considerable (90 lbs) bulk between them. We imagined him saying, “Break it up! Break it up! Move along now…”Oka, like all dogs, had a very firm notion of what was good, orderly behavior and what was not to be allowed. Dogs are strongly oriented to routine, which is one of the things makes them so trainable. They make very specific associations (leash = walkies; vet’s office = horrible things happening to doggies; “Sit!” spoken in front of the refrigerator = sit in front of the refrigerator and no place else). We monkeys like to interpret this as our dogs having fixed ideas about the Way Things Should Be.

Oka’s Rules (as interpreted by his resident monkeys) included:

Cats shall not hiss at one another. Cats have razor blades on their feet and must not be closely approached.Deborah must be accompanied to and from the laundry area in the garage.The sole redeeming value of company is that the Evil Laser Bug comes out to play (therefore, Oka hung out in the living room, patiently watching the carpet for the first sign of the red dot.)The blue horse ball must be herded and barked at (see photo).Bodies of water deeper than a couple of inches are evil.Although of the same breed, Tajji has a different temperament and background. She’s only mildly interested in cat sparring and has shown no inclination to interfere. On the other hand, she has very strong opinions on her responsibility to keep an eye on her monkeys at all times. She’s willing to put up with one of us being behind a closed door if she can see the other. We found out very early that if only one of us was at home and if we closed but did not lock a door, for example a bathroom door, she would nose the door open. She can’t manage round door knobs, but she clearly knows how to push with paws and body weight. She will peek into the room and, having ascertained that the monkey within is not in distress, quietly withdraw. This has happened far too often to be an accident. We believe it was part of her training. So her list might read:

Monkeys must be monitored for well-being.A monkey behind a closed door must be checked on; a monkey that is unstable (I recently sprained an ankle) is clearly in need of assistance and requires a dog.Any monkey-not-of-family coming to the door must be barked at as loudly as possible.Cats are interesting and play fun games.Bodies of water deeper than a couple of inches must be jumped in with much happy splashing.In turns out that despite her excellent seeing eye dog training, Tajji lacks many of the skills of a family/companion dog, including the ability to walk calmly past other dogs, whether they are barking furiously from the sanctuary of their own fenced yards or on leashes on their own walks. When she’s excited, she’s not capable of responding to verbal commands or hand signals. She needs our help in learning to calm herself, and we’ve begun the process by building on her foundational clicker training (click = tasty treat, classical conditioning) with a relaxation protocol. This is a series of distraction tasks in which the dog is asked to sit quietly for increasing lengths of time while her monkey does various things: standing there, counting out loud, taking a few steps forward, backward, or sideways, clapping, jogging in place… At first, we practice in a quiet, familiar place, but as we go on, we’ll add distractions. Eventually we’ll enroll her in a “Reactive Rover” class where she’ll have graduated contacts with other dogs while remaining calm and focused on her monkeys. That should give us the basis for working with her on our neighborhood walks.

(One of the very cool things about these two pictures is you can see how similar in appearance the two dogs are. Oka was a large GSD at 90 lbs, and Tajji is about 65-70, but despite all their similarities, they are very different fur-people.)

Published on March 29, 2014 10:31

March 24, 2014

[rant] Ethics in Fiction: Don't Glamorize Murder

I've been thinking about my best friend, who died last year from ovarian cancer, and about my mother, who was raped and murdered by a neighbor teenager on drugs in 1986. Over the last couple of decades since the latter, I've exchanged stories (and tears, and laughter, and anguish) with other family members of murder victims. Sometimes when I read a story in which killing someone is presented as praiseworthy, I want to scream at the author, "Do you have any idea what you're doing? Do you understand how much pain your characters are causing?" I want to sit down with the writers and make them listen to what it's like to lose someone you love and all the years you might have had together for no good reason. I'm feeling really angry about it right now. Hence the rant below.

I've been thinking about my best friend, who died last year from ovarian cancer, and about my mother, who was raped and murdered by a neighbor teenager on drugs in 1986. Over the last couple of decades since the latter, I've exchanged stories (and tears, and laughter, and anguish) with other family members of murder victims. Sometimes when I read a story in which killing someone is presented as praiseworthy, I want to scream at the author, "Do you have any idea what you're doing? Do you understand how much pain your characters are causing?" I want to sit down with the writers and make them listen to what it's like to lose someone you love and all the years you might have had together for no good reason. I'm feeling really angry about it right now. Hence the rant below.I admit that I cannot comprehend why anyone would think that deliberately ending someone's life is laudable. Yes, things happen by accident. People drive around in lethal weapons all the time. People get angry or frightened and lash out. But writing a story is not something that's over in a flash and can never be taken back. It's an act of deliberate creation and as such, calls on us to be mindful. Listen, folks. Life is all too brief, and incredibly precious. It's totally not okay with me to deliberately cut short a human life. For greed, for bigotry, for revenge, for patriotism. In fiction we often do kill off characters. If you do it, do it with full awareness of the cost.

Don't say it's only entertainment. That is such a bullshit excuse for not paying attention to human suffering. Go shoot up tin cans or climb a mountain instead of filling your stories with shooting galleries. Scream at clouds. Get some professional help - but don't pretend that blowing up characters left and right has no consequences. It's even worse if your "hero" is laughing and spouting nonsense like "That'll teach them" or "They had it coming."

Don't say fiction has nothing to do with emotions or healing, and therefore the author has no responsibility for how readers react. Good fiction has structure, tension, and resolution. The Greek playwrights understood this. Shakespeare knew it. So should you. Even in a tragedy, we want a sense of emotional closure and order. That's also why we love mysteries and police procedurals so much -- because at the end, no matter how difficult the problem or how hopeless the situation, we're left with a sense of restored order. We humans crave justice even when we can't agree on what it is. Fiction may not be literally true, but it must be emotionally true. Life is precious and all too short. Every single human being is unique. Murder, singly or by the millions, has consequences.

Don't say I'm being overreactive or too sensitive. If you haven't lost anyone you love to violence, I truly hope you never do. But between the obscenely high murder rate in this country, not to mention the deaths due to preventable firearms/weapons accidents, and one war after another, chances are you do know someone who died before their time and a family or twelve who are still grieving. Do you think it's fine to tell them not to feel their pain? To "snap out of it"? (Ask anyone with PTSD how well that works.)

Don't use the excuse that a story has to have conflict to be emotionally satisfying or that without physical conflict and victory, the story would be boring pablum. I'm no suggesting that fiction has to be lovey-dovey feel-good. People do die and people do kill one another -- but such actions affect all the survivors. They create moral injury to those who kill, they torture the families of the killers, and they deeply wound those who grapple with grief and trying to make sense out of violence.

Does this mean you can never portray a sociopath or a dedicated soldier who does what he's told, points his gun and fires it as ordered, for a worthy cause? Of course not. What would the world of fiction be without Hannibal Lector, ninja assassins, and innumerable spear carriers? But that's only the surface level. Each of us, and each character, lives in community, whether it's family or other child-raising institution, village, nation, platoon, sewing circle, professional organization, tennis team, internet chat room. Our actions have consequences. You don't have to spell them out in psychological detail. Often all that is necessary is a suggestion that more is happening "off the page," a space in which the reader's own experience can be evoked.

Please don't tell me that because a fictional killing is "justified," that those who slaughter in the name of necessity and good are immune to the negative effects of their experience. If we've learned anything during the last two hundred years about what war does to veterans, it is that no matter how "good" the war is, they come home wounded. Some of them are so crippled, they end up addicts, vagrants, or suicides. Others are able to compartmentalize their experiences well enough to make something of the rest of their lives, as long as they don't have to think or talk about the most devastating things that happened.

Go deep in your fiction. Go true. And go with compassion.

Here endeth the rant.

The painting of Cain murdering Abel is by Daniele Crespi, about 1618

Published on March 24, 2014 12:38