Deborah J. Ross's Blog, page 118

June 29, 2015

Guest Blog: Steven Harper on Greek Mythology and Sexual Abuse

Several years ago, I realized I wasn't dealing with my son's autism diagnosis very well. Too much rage, too much helplessness. Just too much. So I started seeing a counselor, and I saw her for several years.

Several years ago, I realized I wasn't dealing with my son's autism diagnosis very well. Too much rage, too much helplessness. Just too much. So I started seeing a counselor, and I saw her for several years.During that time, I decided I wanted to write about Ganymede, the teenager who was kidnapped by Zeus to serve as his cupbearer on Olympus. Zeus sees Ganymede on the earth below, decides he's the coolest kid ever, changes into an eagle, and snatches Ganymede up to Olympus. Zeus then persuades Hebe to make Ganymede immortal, then dumps Hebe as his cupbearer and gives that exalted position to Ganymede.

Only two and a half stories about Ganymede have survived--the story of his kidnapping, a mention in the Iliad about Zeus giving Ganymede's father a set of horses in payment for the loss of his son (that's the half), and a story in which Ganymede loses a game of dice against Eros, and gets mad at him. That's it.

When I got older and read the actual material instead of the summaries and children's versions, I learned that Ganymede was more than Zeus's cupbearer. Zeus also took Ganymede to his bed. This was part of Greek culture--a powerful man would often serve as a mentor/teacher/second father/love interest to a teenaged male. Usually the parents went along with this: "Good news, son! Your uncle has offered to be your mentor!" So Ganymede was a mythological parallel to this mortal custom.

The stories, however, never went into what it was like. What was it LIKE for Ganymede to be

snatched away from his family and friends and suddenly make into the cupbearer and lover of the king of gods? You have the ultimate mentor, but it wasn't anything you'd asked for. Your culture

teaches you that being taken to this guy's bed is a good thing, or at least something you can put up with because all of us men went through it, but how do you =really= handle it?

teaches you that being taken to this guy's bed is a good thing, or at least something you can put up with because all of us men went through it, but how do you =really= handle it? I ended up using my therapist as a resource here. She had counseled many survivors of sexual assault and was an expert. I told her about the book and said my theory was that a teenager in Ganymede's position would have a lot of mixed feelings.

Sexual assault victims often feel shame because our society has (incorrectly) decreed that victims of sexual assault have done something wrong, that they're bad people who have become further soiled. But Ganymede's culture says that being chosen as a mentee is an honor and a duty, and if you're chosen by the king of gods himself, you must be an amazing person.

And yet . . .

Ganymede at a stroke loses his family, his friends, and his home. He changes from a mortal into an immortal. He is thrust into a group of powerful people who see him as a pawn in a greater game that Ganymede himself doesn't quite understand. He's at the beck and call of Zeus, who does some pretty dreadful things. And he'll be a teenager for the rest of his immortal life.

Some major mixed feelings there.

My counselor agreed. "This would be way too complex for it to be one-sided," she said (or my notes

say she said). "He would love it one moment and hate it the next. There would likely be periods of great sadness and great happiness until he adjusted. You can love and hate someone--people do that all the time, especially when it comes to sex, or to someone you're =supposed= to love but aren't sure you do, or with someone you think you love but don't understand why. Don't be afraid to show that between Ganymede and Zeus."

say she said). "He would love it one moment and hate it the next. There would likely be periods of great sadness and great happiness until he adjusted. You can love and hate someone--people do that all the time, especially when it comes to sex, or to someone you're =supposed= to love but aren't sure you do, or with someone you think you love but don't understand why. Don't be afraid to show that between Ganymede and Zeus."I set out to explore this in DANNY. Or at least, partly. Half the book is set in ancient Greece and half the book is set in modern America. Danny tells Ganymede's story while he tells his own, and the two overlap in strange ways. It's the most complicated, layered novel I've ever written, with plenty of shout-outs to lovers of Greek mythology.

Available at Book View Cafe: http://bookviewcafe.com/bookstore/book/danny/

Steven's Blog: http://spiziks.livejournal.com

Steven's web page: http://www.stevenpiziks.com

Published on June 29, 2015 01:00

June 27, 2015

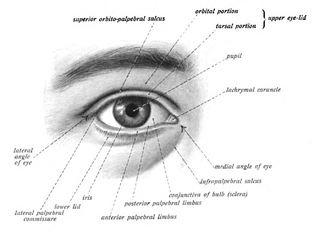

Cataract Journey 2: Choices

With my diagnosis of cataracts (in both eyes), I began to consider my alternatives. The simplest, which is to do nothing and rely on eyeglasses for increasingly inadequate visual correction, was not very appealing, especially since lens replacement surgery was now “medically necessary.” Medicare, like most insurance plans, covers only the bare minimum: a single focus (“monofocal”) artificial replacement lens, usually for distance, with the natural lens being removed and the new one inserted by scalpel. Monofocal lenses give most people excellent distance vision, although they do not correct for astigmatism, and usually require the use of glasses for reading and intermediate distance work.

With my diagnosis of cataracts (in both eyes), I began to consider my alternatives. The simplest, which is to do nothing and rely on eyeglasses for increasingly inadequate visual correction, was not very appealing, especially since lens replacement surgery was now “medically necessary.” Medicare, like most insurance plans, covers only the bare minimum: a single focus (“monofocal”) artificial replacement lens, usually for distance, with the natural lens being removed and the new one inserted by scalpel. Monofocal lenses give most people excellent distance vision, although they do not correct for astigmatism, and usually require the use of glasses for reading and intermediate distance work.These are not the only lenses available. Lenses can be toric (astigmatism correcting), or can correct for more than one distance. Multifocal lenses can provide a full range of vision (or so the literature says), including presbyopia, the difficult in reading that comes with age, but they can also result in halos around street lights and other visual difficulties at night. They also don’t come in all powers of correction. Accommodative lenses can correct for distance and intermediate vision, which means that glasses may be needed for reading; they flex like a normal, healthy lens. Even more technological innovations are in the works, especially as baby boomers age and demand better solutions.

Then there are choices as to how the surgery is done, the traditional scalpel, or femtosecond lasers. The benefits of the laser are that it is more precise and it can correct mild astigmatism at the same time. (Astigmatism arises when the cornea is shaped like a football instead of a soccer ball, resulting in multiple focal points; in pain speech, everything, near or far, is blurry.)

My first reaction was that the price of the special lenses and the laser surgery was beyond my budget. I considered going with just what Medicare would cover, which would mean using glasses for reading or computer work, and also to correct my astigmatism. I hadn’t even considered that I might be able to see clearly without glasses (except for really close-up stuff like removing splinters, where it makes sense to use magnification). Once I started to imagine that possibility, especially in view of the likelihood that I will have this surgery only once in my lifetime, I saw how I was automatically giving privilege to money over quality of life. I allowed myself to consider what I wanted, instead of the cheapest alternative. I had to practice saying, “You’re worth it,” and “You deserve the best,” things I had said so many times to other folks but rarely to myself.

My husband, dear soul, immediately agreed with me. I talked with our financial advisers about how big a bite this might take out of our retirement funds. Then, when least expected, we got a windfall from a couple of sources. I joked that the universe wanted me to be able to see clearly. I remembered a line from Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way: “Leap and the net will appear.” This wasn’t exactly leaping, not with all the number juggling and planning, but I appreciated the reminder to dream beyond limitations.

The next step was a series of precise measurements of my eyeballs and a discussion about what plan would give me the best visual outcome. I knew I wanted the laser surgery because it would correct my astigmatism and offer the possibility of a special lens. My ophthalmologist recommended the accommodative lenses, which he felt might give me good reading vision as well as midrange and distance, with less risk of problems driving at night. An additional advantage to this combination is that if there is any “fine tuning” by LASIK necessary, that will be included in the fee.

I’m scheduled for August, one eye at a time with 2 weeks in between, and I have a huge bag of different kinds of eye drops and a complicated regimen to follow, beginning 3 days before the first surgery. The interval will be difficult, as I will still need correction in the non-surgical eye, so I’m hoping my optometrist can pop out the lens on the surgical side and things won’t look too, too weird. But I’m prepared in the event that they do.

Stay tuned!

Published on June 27, 2015 01:00

June 25, 2015

Revision Round Table 3: Kari Sperring, Marie Brennan

So you've finished your novel -- but have you? That first draft needs work, but where to begin? In

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

Kari Sperring:Ah, revisions.

I’m revising a book right now, and, as a result, my instinctive response to any question about revisions is ‘revisions are the worst. Apart from writing the first draft. That’s the worst, too.’ When it comes to writing, I definitely tend to the Eeyore. Whatever I’m doing right now is the hardest thing, the most uncontrolled, unfocused, worrisome thing.

I’m a very ill-disciplined writer. For preference, I write without an outline – and if I do outline, it tends to consist of a handful of possible scenes plus notes on theme and feel. My desk is littered with scraps of paper on which I have scrawled ideas for future scenes and plot-turns, many of them only semi-legible and usually out of order. Whether or not I get to them is very random: it depends on what turn the book takes and on what I remember. None of which helps when it comes to revising.

With both Living With Ghosts and the book I’m currently working on, I wrote a complete first draft and then rewrote the book from scratch, ending up with a different plot, new characters, and a different outcome. Quenfrida didn’t enter LWG until draft 2. Nor did Joyain. The first draft of the current project seemed to consist mainly of walks and conversations. This new one is full of riots and acts of sabotage, and one of the protagonists is currently disembodied. It’s not the book it was, and I hope it’s better for it, but right now – as always seems to be the case with me and revisions – it feels vast and sprawling and random, a morass of scenes and ideas galloping off in nine different directions, and me in the middle trying desperately to get the whole thing back under control.

But revisions are crucial. I’m a slow writer, as well as a messy one, and my early drafts are littered with plot wisps and abandoned meanders, as I go through and discard ideas. Revising not only lets me find these and excise or complete them, it lets me see where the book needs expansion and reinforcement, even if I don’t always know how to do that, exactly. There is always a Perfect Book, hovering just out of reach over the words and chapters. Despite the drafting and redrafting I did on LWG, it didn’t really come properly into focus until it and I landed on the desk of my editor at DAW books, Sheila Gilbert. I had put it in a drawer for a decade, I had reworked it at least 6 times, but even then I remained too close to it. Sheila saw things I had missed, and showed me how to make my workmanlike draft into, I hope, a good one. A good editor is worth their weight in rubies and should be celebrated from the mountaintops. Right now, the revisions I’m working on – the new book has the working title A Fire of Bones – have been informed and tuned by Sheila’s keen eye, and once again, I think the book is better for it.

Even though, as I write them, as I write this, my brain is telling me that revisions are, like first draft, the worst.

Kari Sperring grew up dreaming of joining the musketeers and saving France, only to discover that the company had been disbanded in 1776. Disappointed, she became a historian instead and as Kari Maund has written and published five books and many articles on Celtic and Viking history and co-authored a book on the history and real people behind her favorite novel, The Three Musketeers (with Phil Nanson). She’s been writing as long as she can remember and completed her first novel at the age of eight (twelve pages long and about ponies). She’s been a barmaid, a tax officer, a P.A. and a university lecturer, and has found that her fascinations, professional or hobby-level, feed and expand into her fiction. Living With Ghosts, her first novel, evolved from her love of France and its history, ghosts, mysteries, Celtic culture, strange magic, sharks, and sword-fights: The Grass King’s Concubine, has even found a creative role for book-keeping. She lives in Cambridge, England, with her partner Phil (who helps design the sword-fights) and three very determined cats, who guarantee that everything she writes will have been thoroughly sat upon. She’s currently at work on her third and fourth novels at once, because she needs more complications in her life. She can be found at http://www.karisperring .com, on Facebook (Kari Sperring), Twitter (@karisperring) and on Live Journal as la_marquise_de_.

~~o~~

Marie Brennan:There are two core statements that sum up my view of revision:

1) It's a spectrum, and2) It's an iterative process.

By the first, I mean that revising a story can mean anything from fiddling with commas all the way up to throwing out the text and starting over -- though I tend to refer to the latter as "rewriting" rather than "revision." There are no clear boundaries between these levels, either, and I rarely do just one at a time: even if I'm going through trying to cut down a scene for better pacing, I'll add bits here and there to make the text flow better, or delete a paragraph and replace it with something else to fix an issue of characterization. (The main exception is when I'm going through page proofs for a book before publication. Then I have to limit myself to only the smallest of prose changes, for purely logistical reasons.)

By "iterative," I mean that revision often proceeds in multiple stages, and is almost never completely done. There are always more changes I could make, little places (or big ones) where I could improve the story later on. I've only written one story in my career where I feel there is nothing else I can do to polish it -- but the story in question is only 376 words long. At lengths beyond that, perfection is impossible to attain.

It's hard for me to say what my revision process looks like, because lately it's been changing. For years I would write my way through the book from beginning to end; then I would print it out (in a format I call the miniscript) and go through two rounds of edits. The first was the "chainsaw edit," done with a red pen, and aimed at macro-level issues like pacing, continuity, characterization, and so forth. The second was the "line edit," done with a green pen, and aimed at polishing the prose. Straightforward, relatively efficient, and it served me well.

But of course it wasn't really that simple. I would often start off a session by reading through the previous night's work (or multiple nights' worth), and of course I would tweak things as I did so. Sometimes I'd realize that what I'd written really didn't work, and then I had to delete it and replace it. One of my novels didn't even get a miniscript edit right away, though I printed it out for posterity; I knew the first draft was sufficiently bad that the only way to approach the process was to open a new file and start the book over again. With later books, I found myself having to pull out entire strands of plot and replace them before I could move forward in the story, or running close enough to my deadline that I had to start revision while still writing the end of the book. The fourth Memoir of Lady Trent is the first novel in my career I didn't print a miniscript for, because I wound up doing 90% of the revision onscreen before I was done with the draft.

It will probably get a miniscript soon, though, because I'll be revising the book again, this time with editorial feedback. And fundamentally, I read differently -- better -- when the text is on the page than when it's on the screen. I am not enough of a scientist to tell you why this is, but I pay closer attention to the page, see things that would slip past if they were just pixels. This is why I still have a copy-edited manuscript mailed to me, rather than handling everything through Track Changes. (Well, that and the fact that I don't use Microsoft Word, and would rather open my veins with a rusty spoon than start.)

I don't claim my approach to revision is the best, in terms of either results or efficiency. Other people have methods for single-pass revision, or always polish as they go, or habitually throw out their first draft and redo the entire book. If there's one habit I would recommend to every writer, though, it's reading your text out loud. I do this with all short stories, and I even try to do it during copy-edits for novels, because there is nothing else in the world that will make you as aware of your words. You'll find the places where your sentence structure is awkward, where you overuse a particular word or create a distracting rhyme. You'll spot errors that would glide right under your radar in silent reading. And while you're at it, you'll probably improve your ability to perform readings for an audience -- a useful skill for a writer to have.

Fundamentally, though, there's only one rule: make it as good as you can in the time you have.

Marie Brennan is an anthropologist and folklorist who shamelessly pillages her academic fields for material. She has most recently misapplied her professors’ hard work to the Memoirs of Lady TrentA Natural History of Dragons, The Tropic of Serpents, Voyage of the Basilisk, and two more to come). She is also the author of the Onyx Court historical fantasy series (Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, A Star Shall Fall, and With Fate Conspire), the doppelganger duology of Warrior and Witch, the urban fantasy

Lies and Prophecy

, and more than forty short stories.

Marie Brennan is an anthropologist and folklorist who shamelessly pillages her academic fields for material. She has most recently misapplied her professors’ hard work to the Memoirs of Lady TrentA Natural History of Dragons, The Tropic of Serpents, Voyage of the Basilisk, and two more to come). She is also the author of the Onyx Court historical fantasy series (Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, A Star Shall Fall, and With Fate Conspire), the doppelganger duology of Warrior and Witch, the urban fantasy

Lies and Prophecy

, and more than forty short stories.

When she’s not obsessing over historical details too minute for anybody but her to care about, she practices shorin-ryu karate and pretends to be other people in role-playing games (which sometimes find their way into her writing).

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.Kari Sperring:Ah, revisions.

I’m revising a book right now, and, as a result, my instinctive response to any question about revisions is ‘revisions are the worst. Apart from writing the first draft. That’s the worst, too.’ When it comes to writing, I definitely tend to the Eeyore. Whatever I’m doing right now is the hardest thing, the most uncontrolled, unfocused, worrisome thing.

I’m a very ill-disciplined writer. For preference, I write without an outline – and if I do outline, it tends to consist of a handful of possible scenes plus notes on theme and feel. My desk is littered with scraps of paper on which I have scrawled ideas for future scenes and plot-turns, many of them only semi-legible and usually out of order. Whether or not I get to them is very random: it depends on what turn the book takes and on what I remember. None of which helps when it comes to revising.

With both Living With Ghosts and the book I’m currently working on, I wrote a complete first draft and then rewrote the book from scratch, ending up with a different plot, new characters, and a different outcome. Quenfrida didn’t enter LWG until draft 2. Nor did Joyain. The first draft of the current project seemed to consist mainly of walks and conversations. This new one is full of riots and acts of sabotage, and one of the protagonists is currently disembodied. It’s not the book it was, and I hope it’s better for it, but right now – as always seems to be the case with me and revisions – it feels vast and sprawling and random, a morass of scenes and ideas galloping off in nine different directions, and me in the middle trying desperately to get the whole thing back under control.

But revisions are crucial. I’m a slow writer, as well as a messy one, and my early drafts are littered with plot wisps and abandoned meanders, as I go through and discard ideas. Revising not only lets me find these and excise or complete them, it lets me see where the book needs expansion and reinforcement, even if I don’t always know how to do that, exactly. There is always a Perfect Book, hovering just out of reach over the words and chapters. Despite the drafting and redrafting I did on LWG, it didn’t really come properly into focus until it and I landed on the desk of my editor at DAW books, Sheila Gilbert. I had put it in a drawer for a decade, I had reworked it at least 6 times, but even then I remained too close to it. Sheila saw things I had missed, and showed me how to make my workmanlike draft into, I hope, a good one. A good editor is worth their weight in rubies and should be celebrated from the mountaintops. Right now, the revisions I’m working on – the new book has the working title A Fire of Bones – have been informed and tuned by Sheila’s keen eye, and once again, I think the book is better for it.

Even though, as I write them, as I write this, my brain is telling me that revisions are, like first draft, the worst.

Kari Sperring grew up dreaming of joining the musketeers and saving France, only to discover that the company had been disbanded in 1776. Disappointed, she became a historian instead and as Kari Maund has written and published five books and many articles on Celtic and Viking history and co-authored a book on the history and real people behind her favorite novel, The Three Musketeers (with Phil Nanson). She’s been writing as long as she can remember and completed her first novel at the age of eight (twelve pages long and about ponies). She’s been a barmaid, a tax officer, a P.A. and a university lecturer, and has found that her fascinations, professional or hobby-level, feed and expand into her fiction. Living With Ghosts, her first novel, evolved from her love of France and its history, ghosts, mysteries, Celtic culture, strange magic, sharks, and sword-fights: The Grass King’s Concubine, has even found a creative role for book-keeping. She lives in Cambridge, England, with her partner Phil (who helps design the sword-fights) and three very determined cats, who guarantee that everything she writes will have been thoroughly sat upon. She’s currently at work on her third and fourth novels at once, because she needs more complications in her life. She can be found at http://www.karisperring .com, on Facebook (Kari Sperring), Twitter (@karisperring) and on Live Journal as la_marquise_de_.

~~o~~

Marie Brennan:There are two core statements that sum up my view of revision:

1) It's a spectrum, and2) It's an iterative process.

By the first, I mean that revising a story can mean anything from fiddling with commas all the way up to throwing out the text and starting over -- though I tend to refer to the latter as "rewriting" rather than "revision." There are no clear boundaries between these levels, either, and I rarely do just one at a time: even if I'm going through trying to cut down a scene for better pacing, I'll add bits here and there to make the text flow better, or delete a paragraph and replace it with something else to fix an issue of characterization. (The main exception is when I'm going through page proofs for a book before publication. Then I have to limit myself to only the smallest of prose changes, for purely logistical reasons.)

By "iterative," I mean that revision often proceeds in multiple stages, and is almost never completely done. There are always more changes I could make, little places (or big ones) where I could improve the story later on. I've only written one story in my career where I feel there is nothing else I can do to polish it -- but the story in question is only 376 words long. At lengths beyond that, perfection is impossible to attain.

It's hard for me to say what my revision process looks like, because lately it's been changing. For years I would write my way through the book from beginning to end; then I would print it out (in a format I call the miniscript) and go through two rounds of edits. The first was the "chainsaw edit," done with a red pen, and aimed at macro-level issues like pacing, continuity, characterization, and so forth. The second was the "line edit," done with a green pen, and aimed at polishing the prose. Straightforward, relatively efficient, and it served me well.

But of course it wasn't really that simple. I would often start off a session by reading through the previous night's work (or multiple nights' worth), and of course I would tweak things as I did so. Sometimes I'd realize that what I'd written really didn't work, and then I had to delete it and replace it. One of my novels didn't even get a miniscript edit right away, though I printed it out for posterity; I knew the first draft was sufficiently bad that the only way to approach the process was to open a new file and start the book over again. With later books, I found myself having to pull out entire strands of plot and replace them before I could move forward in the story, or running close enough to my deadline that I had to start revision while still writing the end of the book. The fourth Memoir of Lady Trent is the first novel in my career I didn't print a miniscript for, because I wound up doing 90% of the revision onscreen before I was done with the draft.

It will probably get a miniscript soon, though, because I'll be revising the book again, this time with editorial feedback. And fundamentally, I read differently -- better -- when the text is on the page than when it's on the screen. I am not enough of a scientist to tell you why this is, but I pay closer attention to the page, see things that would slip past if they were just pixels. This is why I still have a copy-edited manuscript mailed to me, rather than handling everything through Track Changes. (Well, that and the fact that I don't use Microsoft Word, and would rather open my veins with a rusty spoon than start.)

I don't claim my approach to revision is the best, in terms of either results or efficiency. Other people have methods for single-pass revision, or always polish as they go, or habitually throw out their first draft and redo the entire book. If there's one habit I would recommend to every writer, though, it's reading your text out loud. I do this with all short stories, and I even try to do it during copy-edits for novels, because there is nothing else in the world that will make you as aware of your words. You'll find the places where your sentence structure is awkward, where you overuse a particular word or create a distracting rhyme. You'll spot errors that would glide right under your radar in silent reading. And while you're at it, you'll probably improve your ability to perform readings for an audience -- a useful skill for a writer to have.

Fundamentally, though, there's only one rule: make it as good as you can in the time you have.

Marie Brennan is an anthropologist and folklorist who shamelessly pillages her academic fields for material. She has most recently misapplied her professors’ hard work to the Memoirs of Lady TrentA Natural History of Dragons, The Tropic of Serpents, Voyage of the Basilisk, and two more to come). She is also the author of the Onyx Court historical fantasy series (Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, A Star Shall Fall, and With Fate Conspire), the doppelganger duology of Warrior and Witch, the urban fantasy

Lies and Prophecy

, and more than forty short stories.

Marie Brennan is an anthropologist and folklorist who shamelessly pillages her academic fields for material. She has most recently misapplied her professors’ hard work to the Memoirs of Lady TrentA Natural History of Dragons, The Tropic of Serpents, Voyage of the Basilisk, and two more to come). She is also the author of the Onyx Court historical fantasy series (Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, A Star Shall Fall, and With Fate Conspire), the doppelganger duology of Warrior and Witch, the urban fantasy

Lies and Prophecy

, and more than forty short stories.When she’s not obsessing over historical details too minute for anybody but her to care about, she practices shorin-ryu karate and pretends to be other people in role-playing games (which sometimes find their way into her writing).

Published on June 25, 2015 01:00

Revsion Round Table 3: Kari Sperring, Marie Brennan

So you've finished your novel -- but have you? That first draft needs work, but where to begin? In

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

Kari Sperring:Ah, revisions.

I’m revising a book right now, and, as a result, my instinctive response to any question about revisions is ‘revisions are the worst. Apart from writing the first draft. That’s the worst, too.’ When it comes to writing, I definitely tend to the Eeyore. Whatever I’m doing right now is the hardest thing, the most uncontrolled, unfocused, worrisome thing.

I’m a very ill-disciplined writer. For preference, I write without an outline – and if I do outline, it tends to consist of a handful of possible scenes plus notes on theme and feel. My desk is littered with scraps of paper on which I have scrawled ideas for future scenes and plot-turns, many of them only semi-legible and usually out of order. Whether or not I get to them is very random: it depends on what turn the book takes and on what I remember. None of which helps when it comes to revising.

With both Living With Ghosts and the book I’m currently working on, I wrote a complete first draft and then rewrote the book from scratch, ending up with a different plot, new characters, and a different outcome. Quenfrida didn’t enter LWG until draft 2. Nor did Joyain. The first draft of the current project seemed to consist mainly of walks and conversations. This new one is full of riots and acts of sabotage, and one of the protagonists is currently disembodied. It’s not the book it was, and I hope it’s better for it, but right now – as always seems to be the case with me and revisions – it feels vast and sprawling and random, a morass of scenes and ideas galloping off in nine different directions, and me in the middle trying desperately to get the whole thing back under control.

But revisions are crucial. I’m a slow writer, as well as a messy one, and my early drafts are littered with plot wisps and abandoned meanders, as I go through and discard ideas. Revising not only lets me find these and excise or complete them, it lets me see where the book needs expansion and reinforcement, even if I don’t always know how to do that, exactly. There is always a Perfect Book, hovering just out of reach over the words and chapters. Despite the drafting and redrafting I did on LWG, it didn’t really come properly into focus until it and I landed on the desk of my editor at DAW books, Sheila Gilbert. I had put it in a drawer for a decade, I had reworked it at least 6 times, but even then I remained too close to it. Sheila saw things I had missed, and showed me how to make my workmanlike draft into, I hope, a good one. A good editor is worth their weight in rubies and should be celebrated from the mountaintops. Right now, the revisions I’m working on – the new book has the working title A Fire of Bones – have been informed and tuned by Sheila’s keen eye, and once again, I think the book is better for it.

Even though, as I write them, as I write this, my brain is telling me that revisions are, like first draft, the worst.

Kari Sperring grew up dreaming of joining the musketeers and saving France, only to discover that the company had been disbanded in 1776. Disappointed, she became a historian instead and as Kari Maund has written and published five books and many articles on Celtic and Viking history and co-authored a book on the history and real people behind her favorite novel, The Three Musketeers (with Phil Nanson). She’s been writing as long as she can remember and completed her first novel at the age of eight (twelve pages long and about ponies). She’s been a barmaid, a tax officer, a P.A. and a university lecturer, and has found that her fascinations, professional or hobby-level, feed and expand into her fiction. Living With Ghosts, her first novel, evolved from her love of France and its history, ghosts, mysteries, Celtic culture, strange magic, sharks, and sword-fights: The Grass King’s Concubine, has even found a creative role for book-keeping. She lives in Cambridge, England, with her partner Phil (who helps design the sword-fights) and three very determined cats, who guarantee that everything she writes will have been thoroughly sat upon. She’s currently at work on her third and fourth novels at once, because she needs more complications in her life. She can be found at http://www.karisperring .com, on Facebook (Kari Sperring), Twitter (@karisperring) and on Live Journal as la_marquise_de_.

~~o~~

Marie Brennan:There are two core statements that sum up my view of revision:

1) It's a spectrum, and2) It's an iterative process.

By the first, I mean that revising a story can mean anything from fiddling with commas all the way up to throwing out the text and starting over -- though I tend to refer to the latter as "rewriting" rather than "revision." There are no clear boundaries between these levels, either, and I rarely do just one at a time: even if I'm going through trying to cut down a scene for better pacing, I'll add bits here and there to make the text flow better, or delete a paragraph and replace it with something else to fix an issue of characterization. (The main exception is when I'm going through page proofs for a book before publication. Then I have to limit myself to only the smallest of prose changes, for purely logistical reasons.)

By "iterative," I mean that revision often proceeds in multiple stages, and is almost never completely done. There are always more changes I could make, little places (or big ones) where I could improve the story later on. I've only written one story in my career where I feel there is nothing else I can do to polish it -- but the story in question is only 376 words long. At lengths beyond that, perfection is impossible to attain.

It's hard for me to say what my revision process looks like, because lately it's been changing. For years I would write my way through the book from beginning to end; then I would print it out (in a format I call the miniscript) and go through two rounds of edits. The first was the "chainsaw edit," done with a red pen, and aimed at macro-level issues like pacing, continuity, characterization, and so forth. The second was the "line edit," done with a green pen, and aimed at polishing the prose. Straightforward, relatively efficient, and it served me well.

But of course it wasn't really that simple. I would often start off a session by reading through the previous night's work (or multiple nights' worth), and of course I would tweak things as I did so. Sometimes I'd realize that what I'd written really didn't work, and then I had to delete it and replace it. One of my novels didn't even get a miniscript edit right away, though I printed it out for posterity; I knew the first draft was sufficiently bad that the only way to approach the process was to open a new file and start the book over again. With later books, I found myself having to pull out entire strands of plot and replace them before I could move forward in the story, or running close enough to my deadline that I had to start revision while still writing the end of the book. The fourth Memoir of Lady Trent is the first novel in my career I didn't print a miniscript for, because I wound up doing 90% of the revision onscreen before I was done with the draft.

It will probably get a miniscript soon, though, because I'll be revising the book again, this time with editorial feedback. And fundamentally, I read differently -- better -- when the text is on the page than when it's on the screen. I am not enough of a scientist to tell you why this is, but I pay closer attention to the page, see things that would slip past if they were just pixels. This is why I still have a copy-edited manuscript mailed to me, rather than handling everything through Track Changes. (Well, that and the fact that I don't use Microsoft Word, and would rather open my veins with a rusty spoon than start.)

I don't claim my approach to revision is the best, in terms of either results or efficiency. Other people have methods for single-pass revision, or always polish as they go, or habitually throw out their first draft and redo the entire book. If there's one habit I would recommend to every writer, though, it's reading your text out loud. I do this with all short stories, and I even try to do it during copy-edits for novels, because there is nothing else in the world that will make you as aware of your words. You'll find the places where your sentence structure is awkward, where you overuse a particular word or create a distracting rhyme. You'll spot errors that would glide right under your radar in silent reading. And while you're at it, you'll probably improve your ability to perform readings for an audience -- a useful skill for a writer to have.

Fundamentally, though, there's only one rule: make it as good as you can in the time you have.

Marie Brennan is an anthropologist and folklorist who shamelessly pillages her academic fields for material. She has most recently misapplied her professors’ hard work to the Memoirs of Lady TrentA Natural History of Dragons, The Tropic of Serpents, Voyage of the Basilisk, and two more to come). She is also the author of the Onyx Court historical fantasy series (Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, A Star Shall Fall, and With Fate Conspire), the doppelganger duology of Warrior and Witch, the urban fantasy

Lies and Prophecy

, and more than forty short stories.

Marie Brennan is an anthropologist and folklorist who shamelessly pillages her academic fields for material. She has most recently misapplied her professors’ hard work to the Memoirs of Lady TrentA Natural History of Dragons, The Tropic of Serpents, Voyage of the Basilisk, and two more to come). She is also the author of the Onyx Court historical fantasy series (Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, A Star Shall Fall, and With Fate Conspire), the doppelganger duology of Warrior and Witch, the urban fantasy

Lies and Prophecy

, and more than forty short stories.

When she’s not obsessing over historical details too minute for anybody but her to care about, she practices shorin-ryu karate and pretends to be other people in role-playing games (which sometimes find their way into her writing).

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.Kari Sperring:Ah, revisions.

I’m revising a book right now, and, as a result, my instinctive response to any question about revisions is ‘revisions are the worst. Apart from writing the first draft. That’s the worst, too.’ When it comes to writing, I definitely tend to the Eeyore. Whatever I’m doing right now is the hardest thing, the most uncontrolled, unfocused, worrisome thing.

I’m a very ill-disciplined writer. For preference, I write without an outline – and if I do outline, it tends to consist of a handful of possible scenes plus notes on theme and feel. My desk is littered with scraps of paper on which I have scrawled ideas for future scenes and plot-turns, many of them only semi-legible and usually out of order. Whether or not I get to them is very random: it depends on what turn the book takes and on what I remember. None of which helps when it comes to revising.

With both Living With Ghosts and the book I’m currently working on, I wrote a complete first draft and then rewrote the book from scratch, ending up with a different plot, new characters, and a different outcome. Quenfrida didn’t enter LWG until draft 2. Nor did Joyain. The first draft of the current project seemed to consist mainly of walks and conversations. This new one is full of riots and acts of sabotage, and one of the protagonists is currently disembodied. It’s not the book it was, and I hope it’s better for it, but right now – as always seems to be the case with me and revisions – it feels vast and sprawling and random, a morass of scenes and ideas galloping off in nine different directions, and me in the middle trying desperately to get the whole thing back under control.

But revisions are crucial. I’m a slow writer, as well as a messy one, and my early drafts are littered with plot wisps and abandoned meanders, as I go through and discard ideas. Revising not only lets me find these and excise or complete them, it lets me see where the book needs expansion and reinforcement, even if I don’t always know how to do that, exactly. There is always a Perfect Book, hovering just out of reach over the words and chapters. Despite the drafting and redrafting I did on LWG, it didn’t really come properly into focus until it and I landed on the desk of my editor at DAW books, Sheila Gilbert. I had put it in a drawer for a decade, I had reworked it at least 6 times, but even then I remained too close to it. Sheila saw things I had missed, and showed me how to make my workmanlike draft into, I hope, a good one. A good editor is worth their weight in rubies and should be celebrated from the mountaintops. Right now, the revisions I’m working on – the new book has the working title A Fire of Bones – have been informed and tuned by Sheila’s keen eye, and once again, I think the book is better for it.

Even though, as I write them, as I write this, my brain is telling me that revisions are, like first draft, the worst.

Kari Sperring grew up dreaming of joining the musketeers and saving France, only to discover that the company had been disbanded in 1776. Disappointed, she became a historian instead and as Kari Maund has written and published five books and many articles on Celtic and Viking history and co-authored a book on the history and real people behind her favorite novel, The Three Musketeers (with Phil Nanson). She’s been writing as long as she can remember and completed her first novel at the age of eight (twelve pages long and about ponies). She’s been a barmaid, a tax officer, a P.A. and a university lecturer, and has found that her fascinations, professional or hobby-level, feed and expand into her fiction. Living With Ghosts, her first novel, evolved from her love of France and its history, ghosts, mysteries, Celtic culture, strange magic, sharks, and sword-fights: The Grass King’s Concubine, has even found a creative role for book-keeping. She lives in Cambridge, England, with her partner Phil (who helps design the sword-fights) and three very determined cats, who guarantee that everything she writes will have been thoroughly sat upon. She’s currently at work on her third and fourth novels at once, because she needs more complications in her life. She can be found at http://www.karisperring .com, on Facebook (Kari Sperring), Twitter (@karisperring) and on Live Journal as la_marquise_de_.

~~o~~

Marie Brennan:There are two core statements that sum up my view of revision:

1) It's a spectrum, and2) It's an iterative process.

By the first, I mean that revising a story can mean anything from fiddling with commas all the way up to throwing out the text and starting over -- though I tend to refer to the latter as "rewriting" rather than "revision." There are no clear boundaries between these levels, either, and I rarely do just one at a time: even if I'm going through trying to cut down a scene for better pacing, I'll add bits here and there to make the text flow better, or delete a paragraph and replace it with something else to fix an issue of characterization. (The main exception is when I'm going through page proofs for a book before publication. Then I have to limit myself to only the smallest of prose changes, for purely logistical reasons.)

By "iterative," I mean that revision often proceeds in multiple stages, and is almost never completely done. There are always more changes I could make, little places (or big ones) where I could improve the story later on. I've only written one story in my career where I feel there is nothing else I can do to polish it -- but the story in question is only 376 words long. At lengths beyond that, perfection is impossible to attain.

It's hard for me to say what my revision process looks like, because lately it's been changing. For years I would write my way through the book from beginning to end; then I would print it out (in a format I call the miniscript) and go through two rounds of edits. The first was the "chainsaw edit," done with a red pen, and aimed at macro-level issues like pacing, continuity, characterization, and so forth. The second was the "line edit," done with a green pen, and aimed at polishing the prose. Straightforward, relatively efficient, and it served me well.

But of course it wasn't really that simple. I would often start off a session by reading through the previous night's work (or multiple nights' worth), and of course I would tweak things as I did so. Sometimes I'd realize that what I'd written really didn't work, and then I had to delete it and replace it. One of my novels didn't even get a miniscript edit right away, though I printed it out for posterity; I knew the first draft was sufficiently bad that the only way to approach the process was to open a new file and start the book over again. With later books, I found myself having to pull out entire strands of plot and replace them before I could move forward in the story, or running close enough to my deadline that I had to start revision while still writing the end of the book. The fourth Memoir of Lady Trent is the first novel in my career I didn't print a miniscript for, because I wound up doing 90% of the revision onscreen before I was done with the draft.

It will probably get a miniscript soon, though, because I'll be revising the book again, this time with editorial feedback. And fundamentally, I read differently -- better -- when the text is on the page than when it's on the screen. I am not enough of a scientist to tell you why this is, but I pay closer attention to the page, see things that would slip past if they were just pixels. This is why I still have a copy-edited manuscript mailed to me, rather than handling everything through Track Changes. (Well, that and the fact that I don't use Microsoft Word, and would rather open my veins with a rusty spoon than start.)

I don't claim my approach to revision is the best, in terms of either results or efficiency. Other people have methods for single-pass revision, or always polish as they go, or habitually throw out their first draft and redo the entire book. If there's one habit I would recommend to every writer, though, it's reading your text out loud. I do this with all short stories, and I even try to do it during copy-edits for novels, because there is nothing else in the world that will make you as aware of your words. You'll find the places where your sentence structure is awkward, where you overuse a particular word or create a distracting rhyme. You'll spot errors that would glide right under your radar in silent reading. And while you're at it, you'll probably improve your ability to perform readings for an audience -- a useful skill for a writer to have.

Fundamentally, though, there's only one rule: make it as good as you can in the time you have.

Marie Brennan is an anthropologist and folklorist who shamelessly pillages her academic fields for material. She has most recently misapplied her professors’ hard work to the Memoirs of Lady TrentA Natural History of Dragons, The Tropic of Serpents, Voyage of the Basilisk, and two more to come). She is also the author of the Onyx Court historical fantasy series (Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, A Star Shall Fall, and With Fate Conspire), the doppelganger duology of Warrior and Witch, the urban fantasy

Lies and Prophecy

, and more than forty short stories.

Marie Brennan is an anthropologist and folklorist who shamelessly pillages her academic fields for material. She has most recently misapplied her professors’ hard work to the Memoirs of Lady TrentA Natural History of Dragons, The Tropic of Serpents, Voyage of the Basilisk, and two more to come). She is also the author of the Onyx Court historical fantasy series (Midnight Never Come, In Ashes Lie, A Star Shall Fall, and With Fate Conspire), the doppelganger duology of Warrior and Witch, the urban fantasy

Lies and Prophecy

, and more than forty short stories.When she’s not obsessing over historical details too minute for anybody but her to care about, she practices shorin-ryu karate and pretends to be other people in role-playing games (which sometimes find their way into her writing).

Published on June 25, 2015 01:00

June 18, 2015

Revision Round Table 2: Judith Tarr, Elizabeth Moon

So you've finished your novel -- but have you? That first draft needs work, but where to begin? In

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

Judith Tarr:

How do you approach revising a book? I prefer to revise than to write first draft. Revision is my reward for slogging through the draft. Since I do most of my "prewriting" either in notes or in my head, and generally have my plot either outlined or again, clear in my head, my drafts tend to be very spare but pretty much complete. My editor will usually tell me to expand; I've never had to cut, I've always had to add. Sometimes a lot.

Of cuss the editorial letter can make me say bad words, because in my dreams I submit a perfect draft that needs no more than a light waft of proofreading before it bursts out upon the world. In reality, if I'm lucky, I don't have to add or change much. If I'm not...well, there was that time I had to rewrite the whole thing with a different but much more appropriate protagonist. Or the time I had to add 50,000 words. Or...

What makes revision different from polishing or rewriting, or is there a difference? Revision for me is what I do after I've received outside input. Usually that's the editorial letter. I don't use beta readers in general; have pulled in a reader once in a while for expert advice or clear-eyed input, but mostly it's just me and my ms. until it meets its editor.

Do you work things out in your head, work only from the manuscript (and if so, on the computer or a printed hard copy), some combination of both? I work on the computer with my editorial letter in hand, with however many passes the ms. needs. Picky stuff first (wording, clarifications, continuity notes, etc.). While I'm going through to get the small stuff cleared up, the back of my mind is mulling over the big stuff: expansion of character roles, plot elements, worldbuilding notes, and so on. Those get done in waves as I can handle them.

I try to find the spot where a change or expansion has the maximum effect. A change in a word or a line at the exact right place can resonate through the whole ms. That's the dream change.

Or, doing the minimum required to make the book work according to my vision and the editor's input. It's the lazy writer's technique, and if I do it right, it makes a huge difference to the quality of the work.

Do you write out takes, read sections aloud?

Nope. I try to make every word count. No exploratory drafts. Sometimes I'll have an outtake in draft, when I go off in the wrong direction, but by the time the editor sees it, I'll be adding rather than subtracting.

Reading existing text aloud doesn't work for me, though I'll often speak the words as I type draft or revision.

What advice, if any, would you give a beginning writer? No one's work is perfect. No one's. Expect to revise. Embrace it. Stay true to your idea, don't let it be gutted by wrongheaded input, but also be open to what your editor has to say. She's probably right--or if she's not, what she has to say might show you how to make your work better anyway.

In connection with this: Let your draft be as messy as it needs to be; just get it on the page in the way that best serves the project and your individual process. Revision is where you worry about cleaning it up and making it shine.

What's been the most useful thing another writer has taught you?Every process is different. Every writer has her own individual way of getting a project written and revised. There's no wrong way to do it--just a whole lot of different ways to make it happen.

Judith Tarr has been a World Fantasy Award nominee for her Alexander the Great novel, Lord of the Two Lands, and won the Crawford Award for her Hound and the Falcon trilogy. She also writes as Caitlin Brennan (The Mountain’s Call and sequels) and Kathleen Bryan (The Serpent and the Rose and sequels). Caitlin published House of the Star, a magical-horse novel. When she is not working on her latest novel or story, she is breeding, raising, and training Lipizzan horses on her farm near Tucson, Arizona.

Judith Tarr has been a World Fantasy Award nominee for her Alexander the Great novel, Lord of the Two Lands, and won the Crawford Award for her Hound and the Falcon trilogy. She also writes as Caitlin Brennan (The Mountain’s Call and sequels) and Kathleen Bryan (The Serpent and the Rose and sequels). Caitlin published House of the Star, a magical-horse novel. When she is not working on her latest novel or story, she is breeding, raising, and training Lipizzan horses on her farm near Tucson, Arizona.

~~o~~

Elizabeth Moon:

How do you approach revising a book? As re-vision--as re-seeing the work in light of what I wanted to accomplish and what's actually on the page, so that its gaps can be filled, its flaws corrected, and so on.

From there, it's a process based on my mother's advice about building something: first concentrate on the design, then the construction, and finally the finish (finishing out, giving it "curb appeal.") Just as, in building a house, you don't start by painting one side of dry wall panels before you know whether a room will have two windows or three, I don't bother with the later stages until the first ones are complete.

Design/structural means making sure the story makes sense as a story, and the kind of story I was trying to write. (IOW, the story has a good arc and doesn't switch gears from a madcap adventure to a blistering social commentary in the last chapter. That's the next book.)

Writers who outline well solve these problems in the outline, but I can't outline, so I look at things like "story arc" and "character arcs" and whether things happen in the right order at this stage. If it's a multi-viewpoint book, this is where entire viewpoint sections are moved as needed to provide the best flow for the reader, the best "Story" shape.

I try (not always successfully!) to do the design/structural revisions during the original several drafts, ending with the "main draft" that will go on to the next stages. Once I have the parts of the story in order, it's time to look at construction-level stuff: the actual writing.

What I'm looking for in this are paragraph level gaps or sources of confusion or boredom for readers. I want to make sure all the parts are sound in themselves and connect with each other smoothly. Infodumps, unwanted repetitions, character "breaks," messy clumps of writerly enthusiasm all meet the Chainsaw of Correction. Sentences out of order within a paragraph, consequences before actions (embarrassing how many times I do that in draft!) meet the Comb of Untangling. Rough or nonexistent transitions get troweled into place and then faired in smoothly to prevent reader-jouncing confusions.

At this point, the finishing work starts--and I hand off some of the work to a couple of good nit-pickers. While they nit-pickers are looking for misspellings, grammatical errors, continuity problems…I'm reading it aloud for flow, listening to the word-music (is it too legato for that scene? Too staccato for that? Is the beat too regular? Does it really express the POV's internal state?) and other details that make it shine.

What makes revision different from polishing or rewriting, or is there a difference? Rewriting is what an editor asks me to do. It derives from the editor's vision, not my original vision--and requires merging the editor's view of the book with mine. Starting with 24 hours of internal whining and bitching and moaning before I'm ready to agree that yes, chapter 23 sucks rocks and we all missed that, and yes, that lovely passage in chapter 31 is totally ear-candy and self-indulgence just like the alpha reader said, and I ignored, hoping to sneak it past the editor. But no, you can't make me take out the puppy: he's going to bite a villain at a critical moment later in the story. (Three whole volumes later, as it turned out, but he did.) (And thank all relevant deities for editors who catch what others have missed.)

For me, polishing is the final stage of revision.

Do you work things out in your head, work only from the manuscript (and if so, on the computer or a printed hard copy), some combination of both? Always from the manuscript, and usually a combination of digital and paper. Whenever something gives me trouble I print it out. I scribble notes to myself on paper. And at times resort to models.

Do you write out takes, read sections aloud? Sometimes both, but always read sections aloud. The out-take writing is usually to clarify something about a character's motivation.

What advice, if any, would you give a beginning writer? Nobody has to know what you actually wrote, as long as what you end up with works. Write freely; revise as much as it needs.

What's been the most useful thing another writer has taught you?

If you can't figure out what's wrong--read it out loud again. The answer's in there.

Elizabeth Moon, a Texas native, is a Marine Corps veteran with degrees in history and biology. She began writing stories in childhood but did not make her first fiction sale until age forty. She has published twenty-three novels, including Nebula Award winner The Speed of Dark, three short-fiction collections including Moon Flights in 2007, and over thirty short-fiction pieces in anthologies and magazines. Her latest book is Kings of the North (second book of Paladin's Legacy) a return to the world of The Deed of Paksenarrion, and the third in that group, Crisis of Vison, is due out in 2012. The first book of Paladin's Legacy, Oath of Fealty, is now in paperback also. In non-writing hours, she enjoys nature photography, gardening, cooking, Renaissance style fencing, messing about with horses, and music, including singing in a church choir. And wasting time online, of course...

Elizabeth Moon, a Texas native, is a Marine Corps veteran with degrees in history and biology. She began writing stories in childhood but did not make her first fiction sale until age forty. She has published twenty-three novels, including Nebula Award winner The Speed of Dark, three short-fiction collections including Moon Flights in 2007, and over thirty short-fiction pieces in anthologies and magazines. Her latest book is Kings of the North (second book of Paladin's Legacy) a return to the world of The Deed of Paksenarrion, and the third in that group, Crisis of Vison, is due out in 2012. The first book of Paladin's Legacy, Oath of Fealty, is now in paperback also. In non-writing hours, she enjoys nature photography, gardening, cooking, Renaissance style fencing, messing about with horses, and music, including singing in a church choir. And wasting time online, of course...

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.

this round table series, I asked professional authors how the approach revision -- not polishing, but truly re-visioning a story.Judith Tarr:

How do you approach revising a book? I prefer to revise than to write first draft. Revision is my reward for slogging through the draft. Since I do most of my "prewriting" either in notes or in my head, and generally have my plot either outlined or again, clear in my head, my drafts tend to be very spare but pretty much complete. My editor will usually tell me to expand; I've never had to cut, I've always had to add. Sometimes a lot.

Of cuss the editorial letter can make me say bad words, because in my dreams I submit a perfect draft that needs no more than a light waft of proofreading before it bursts out upon the world. In reality, if I'm lucky, I don't have to add or change much. If I'm not...well, there was that time I had to rewrite the whole thing with a different but much more appropriate protagonist. Or the time I had to add 50,000 words. Or...

What makes revision different from polishing or rewriting, or is there a difference? Revision for me is what I do after I've received outside input. Usually that's the editorial letter. I don't use beta readers in general; have pulled in a reader once in a while for expert advice or clear-eyed input, but mostly it's just me and my ms. until it meets its editor.

Do you work things out in your head, work only from the manuscript (and if so, on the computer or a printed hard copy), some combination of both? I work on the computer with my editorial letter in hand, with however many passes the ms. needs. Picky stuff first (wording, clarifications, continuity notes, etc.). While I'm going through to get the small stuff cleared up, the back of my mind is mulling over the big stuff: expansion of character roles, plot elements, worldbuilding notes, and so on. Those get done in waves as I can handle them.

I try to find the spot where a change or expansion has the maximum effect. A change in a word or a line at the exact right place can resonate through the whole ms. That's the dream change.

Or, doing the minimum required to make the book work according to my vision and the editor's input. It's the lazy writer's technique, and if I do it right, it makes a huge difference to the quality of the work.

Do you write out takes, read sections aloud?

Nope. I try to make every word count. No exploratory drafts. Sometimes I'll have an outtake in draft, when I go off in the wrong direction, but by the time the editor sees it, I'll be adding rather than subtracting.

Reading existing text aloud doesn't work for me, though I'll often speak the words as I type draft or revision.

What advice, if any, would you give a beginning writer? No one's work is perfect. No one's. Expect to revise. Embrace it. Stay true to your idea, don't let it be gutted by wrongheaded input, but also be open to what your editor has to say. She's probably right--or if she's not, what she has to say might show you how to make your work better anyway.

In connection with this: Let your draft be as messy as it needs to be; just get it on the page in the way that best serves the project and your individual process. Revision is where you worry about cleaning it up and making it shine.

What's been the most useful thing another writer has taught you?Every process is different. Every writer has her own individual way of getting a project written and revised. There's no wrong way to do it--just a whole lot of different ways to make it happen.

Judith Tarr has been a World Fantasy Award nominee for her Alexander the Great novel, Lord of the Two Lands, and won the Crawford Award for her Hound and the Falcon trilogy. She also writes as Caitlin Brennan (The Mountain’s Call and sequels) and Kathleen Bryan (The Serpent and the Rose and sequels). Caitlin published House of the Star, a magical-horse novel. When she is not working on her latest novel or story, she is breeding, raising, and training Lipizzan horses on her farm near Tucson, Arizona.

Judith Tarr has been a World Fantasy Award nominee for her Alexander the Great novel, Lord of the Two Lands, and won the Crawford Award for her Hound and the Falcon trilogy. She also writes as Caitlin Brennan (The Mountain’s Call and sequels) and Kathleen Bryan (The Serpent and the Rose and sequels). Caitlin published House of the Star, a magical-horse novel. When she is not working on her latest novel or story, she is breeding, raising, and training Lipizzan horses on her farm near Tucson, Arizona.~~o~~

Elizabeth Moon:

How do you approach revising a book? As re-vision--as re-seeing the work in light of what I wanted to accomplish and what's actually on the page, so that its gaps can be filled, its flaws corrected, and so on.

From there, it's a process based on my mother's advice about building something: first concentrate on the design, then the construction, and finally the finish (finishing out, giving it "curb appeal.") Just as, in building a house, you don't start by painting one side of dry wall panels before you know whether a room will have two windows or three, I don't bother with the later stages until the first ones are complete.

Design/structural means making sure the story makes sense as a story, and the kind of story I was trying to write. (IOW, the story has a good arc and doesn't switch gears from a madcap adventure to a blistering social commentary in the last chapter. That's the next book.)

Writers who outline well solve these problems in the outline, but I can't outline, so I look at things like "story arc" and "character arcs" and whether things happen in the right order at this stage. If it's a multi-viewpoint book, this is where entire viewpoint sections are moved as needed to provide the best flow for the reader, the best "Story" shape.

I try (not always successfully!) to do the design/structural revisions during the original several drafts, ending with the "main draft" that will go on to the next stages. Once I have the parts of the story in order, it's time to look at construction-level stuff: the actual writing.

What I'm looking for in this are paragraph level gaps or sources of confusion or boredom for readers. I want to make sure all the parts are sound in themselves and connect with each other smoothly. Infodumps, unwanted repetitions, character "breaks," messy clumps of writerly enthusiasm all meet the Chainsaw of Correction. Sentences out of order within a paragraph, consequences before actions (embarrassing how many times I do that in draft!) meet the Comb of Untangling. Rough or nonexistent transitions get troweled into place and then faired in smoothly to prevent reader-jouncing confusions.

At this point, the finishing work starts--and I hand off some of the work to a couple of good nit-pickers. While they nit-pickers are looking for misspellings, grammatical errors, continuity problems…I'm reading it aloud for flow, listening to the word-music (is it too legato for that scene? Too staccato for that? Is the beat too regular? Does it really express the POV's internal state?) and other details that make it shine.

What makes revision different from polishing or rewriting, or is there a difference? Rewriting is what an editor asks me to do. It derives from the editor's vision, not my original vision--and requires merging the editor's view of the book with mine. Starting with 24 hours of internal whining and bitching and moaning before I'm ready to agree that yes, chapter 23 sucks rocks and we all missed that, and yes, that lovely passage in chapter 31 is totally ear-candy and self-indulgence just like the alpha reader said, and I ignored, hoping to sneak it past the editor. But no, you can't make me take out the puppy: he's going to bite a villain at a critical moment later in the story. (Three whole volumes later, as it turned out, but he did.) (And thank all relevant deities for editors who catch what others have missed.)

For me, polishing is the final stage of revision.

Do you work things out in your head, work only from the manuscript (and if so, on the computer or a printed hard copy), some combination of both? Always from the manuscript, and usually a combination of digital and paper. Whenever something gives me trouble I print it out. I scribble notes to myself on paper. And at times resort to models.

Do you write out takes, read sections aloud? Sometimes both, but always read sections aloud. The out-take writing is usually to clarify something about a character's motivation.

What advice, if any, would you give a beginning writer? Nobody has to know what you actually wrote, as long as what you end up with works. Write freely; revise as much as it needs.

What's been the most useful thing another writer has taught you?

If you can't figure out what's wrong--read it out loud again. The answer's in there.

Elizabeth Moon, a Texas native, is a Marine Corps veteran with degrees in history and biology. She began writing stories in childhood but did not make her first fiction sale until age forty. She has published twenty-three novels, including Nebula Award winner The Speed of Dark, three short-fiction collections including Moon Flights in 2007, and over thirty short-fiction pieces in anthologies and magazines. Her latest book is Kings of the North (second book of Paladin's Legacy) a return to the world of The Deed of Paksenarrion, and the third in that group, Crisis of Vison, is due out in 2012. The first book of Paladin's Legacy, Oath of Fealty, is now in paperback also. In non-writing hours, she enjoys nature photography, gardening, cooking, Renaissance style fencing, messing about with horses, and music, including singing in a church choir. And wasting time online, of course...

Elizabeth Moon, a Texas native, is a Marine Corps veteran with degrees in history and biology. She began writing stories in childhood but did not make her first fiction sale until age forty. She has published twenty-three novels, including Nebula Award winner The Speed of Dark, three short-fiction collections including Moon Flights in 2007, and over thirty short-fiction pieces in anthologies and magazines. Her latest book is Kings of the North (second book of Paladin's Legacy) a return to the world of The Deed of Paksenarrion, and the third in that group, Crisis of Vison, is due out in 2012. The first book of Paladin's Legacy, Oath of Fealty, is now in paperback also. In non-writing hours, she enjoys nature photography, gardening, cooking, Renaissance style fencing, messing about with horses, and music, including singing in a church choir. And wasting time online, of course...

Published on June 18, 2015 01:00

June 16, 2015

Cataract Journey Side Note: Lunar Haloes

Over on APOD, I see this beautiful image:

And its description: Rings like this will sometimes appear when the Moon is seen through thin clouds. The effect is created by the quantum mechanical diffraction of light around individual, similarly-sized water droplets in an intervening but mostly-transparent cloud. Since light of different colors has different wavelengths, each color diffracts differently. Lunar Coronae are one of the few quantum mechanical color effects that can be easily seen with the unaided eye.

And I am so relieved that this is a real phenomenon, and not further proof that I need cataract surgery. I don't see multiple colored rings, but a soft halo the same color as the object (white, in the case of the Moon).

And its description: Rings like this will sometimes appear when the Moon is seen through thin clouds. The effect is created by the quantum mechanical diffraction of light around individual, similarly-sized water droplets in an intervening but mostly-transparent cloud. Since light of different colors has different wavelengths, each color diffracts differently. Lunar Coronae are one of the few quantum mechanical color effects that can be easily seen with the unaided eye.

And I am so relieved that this is a real phenomenon, and not further proof that I need cataract surgery. I don't see multiple colored rings, but a soft halo the same color as the object (white, in the case of the Moon).

Published on June 16, 2015 09:53

June 13, 2015

Cataract Journey 1: Diagnosis

For some years now, maybe a decade, I’ve complained about my “old eyes.” I’ve never had good vision without corrective lenses. I think I started wearing glasses in 3rd grade. I remember getting contact lenses in 1960. They were hard lenses, of course, and required a long period of getting used to, all the while putting up with light sensitivity and scratchy, red eyes. They did, however, get me out of having to play softball – which I was so bad at, it was embarrassing – in high school; the first windy day blew so much dust into my eyes, the school let me switch to swimming. For some reason, maybe the steepness of my corneas, the lenses stayed put in water. As a result, I learned to swim.

For some years now, maybe a decade, I’ve complained about my “old eyes.” I’ve never had good vision without corrective lenses. I think I started wearing glasses in 3rd grade. I remember getting contact lenses in 1960. They were hard lenses, of course, and required a long period of getting used to, all the while putting up with light sensitivity and scratchy, red eyes. They did, however, get me out of having to play softball – which I was so bad at, it was embarrassing – in high school; the first windy day blew so much dust into my eyes, the school let me switch to swimming. For some reason, maybe the steepness of my corneas, the lenses stayed put in water. As a result, I learned to swim.For a long time, hard (“rigid gas-permeable”) lenses were a great solution for me. I don’t have issues about handling my eyes, and best of all, they gave me great correction. My brain thought the world had sharp edges. And so it went for many years.

Eventually I ran into one situation or another where I needed glasses. For some strange reason, hospitals want you to take your contacts out. So I got them, even though years would go by without using them. And then, of course, I’d need a different prescription. I got a pair just for reading in bed, part of my night time ritual.

Fast forward a number of decades. Dry, scratchy eyes became more of a problem, especially when working at the computer, and often it seemed as if the lenses couldn’t quite settle (and give me good correction), no matter how many times I blinked. I’d take them out and clean them, and sometimes that would help. Driving at night became more tiring. I could no longer see the night sky clearly, and I was pretty sure I’d been able to, once upon a time.

Eventually, my eyes decided they’d had it with contacts. After a painful bout with “contact lens over-wear,” I was never able to wear them for more than a few hours every day. Then I lost one (a very rare occurrence for me) and decided that was the universe’s way of shutting the door. I got new glasses, both for intermediate (computer, piano) distance and far distance. Night driving got even more difficult, and I noticed I was staying home rather than tackling the twisty mountain roads in my area on rainy nights. Street lights appeared surrounded by soft haloes that did not change when I took my glasses off. Often it would seem that the lenses were dirty or smeared, but they looked okay when I checked. Although my distance glasses corrected me enough so I could drive safely, I had trouble reading street and highway signs at a distance.