Kathleen Flanagan Rollins's Blog, page 8

November 15, 2012

2012 Twelve Days of Christmas Blog Hop

The 2012 Twelve Days of Christmas Blog Hop is happening December 1 – 12!

Misfits and Heroes is once again participating in the 12 Days of Christmas Blog Tour set up by Intoxicated by Books and giving away one copy of Misfits and Heroes: West from Africa each day of the hop. All you have to do is leave your name and email address in the Comments section. No, they won’t be sold or given away to anybody! I’ll remove the information after I get it. Please add how you heard about the Misfits and Heroes blog. Thanks.

Misfits and Heroes: West from Africa is ancient adventure/exploration/magic/spirit intervention. It was named one of Kirkus Reviews Best of 2011, one of only 51 independently published books to make the list and one of only four indie adventure novels.

If the second book in the Misfits and Heroes series, Past the Last Island, is ready by then, winners are welcome to choose that book instead of Misfits and Heroes: West from Africa. Past the Last Island deals with a group of explorers crossing the Pacific from what is now Indonesia, 14,000 years ago.

The winners will be notified by email. The prizes should be in the mail by the end of December.

Thanks for your interest in the blog. Look around for information on ancient people, who were probably more advanced than you thought!

A list of participating blogs will be included soon, so you can visit them all.

Kathleen Flanagan Rollins

August 27, 2012

Ancient Navigators

Did ancient explorers cross oceans to reach the New World?

Many popular theories explaining the peopling of the Americas, including Clovis First (See earlier post on the Clovis theory) claim that people first arrived in the Americas by walking across Beringia, the Ice Age land bridge from Siberia to Alaska around 13,000 years ago. From there they eventually spread overland all the way across and down the Americas.

Monte Verde

Mario Piño, from Chile, and Tom Dillehay, from the USA, provided the best challenge to the Clovis-first theory with their work on the Monte Verde site in Chile (See map). In 1977, they p ublished their findings, which included evidence of human presence at the site 14,200 years ago. The upper level yielded interesting finds, including the remains of 20’ long structures made of walls of poles covered with animal hides, large hearths lined with clay, coprolites containing remnants of 45 different plant species including nine species of seaweed, seeds, nuts, berries, remains of local animals, and wild potatoes. Some of their food came from 150 miles away, indicating either a large gathering area or a functioning food network.

ublished their findings, which included evidence of human presence at the site 14,200 years ago. The upper level yielded interesting finds, including the remains of 20’ long structures made of walls of poles covered with animal hides, large hearths lined with clay, coprolites containing remnants of 45 different plant species including nine species of seaweed, seeds, nuts, berries, remains of local animals, and wild potatoes. Some of their food came from 150 miles away, indicating either a large gathering area or a functioning food network.

In 1997, the Monte Verde dates were rechecked and confirmed by previously doubting archaeologists, some of whom were forced to admit they might need a more complex answer to the question of how people arrived in the Americas.

However, that wasn’t the real shocker. Tom Dillehay knew more than he said in his published paper. He and Piño had excavated a lower level with dates Dillehay knew would never be accepted, so he ignored the lower level in his paper, except to note “although the stratigraphy is intact, the radiocarbon dates are valid, and the human artifacts are genuine, I hesitate to accept this older level without more evidence and without sites of comparable age elsewhere in the Americas.” Later, he admitted he had found “charcoal scatters which may be the remnants of fireplaces next to possible stone and wood artifacts, and these were dated to at least 33,000BC.”

Mario Piño had fewer reservations. He asserted the 35,000 years ago date based on his finds at Monte Verde and corresponding dates from an animal bone found at another archaeological site 120 miles north.

Pedra Furado

Another pivotal discovery was made in South America at a site called Pedra Furado in eastern Brazil. Here, the dates were so revolutionary that few American archaeologists accepted them. In 1986, a woman named Niede Guidon published a paper claiming she had discovered the oldest known site of human habitation in the Americas (at least 33,000 years ago; some dates range from 41,000 to 56,000 years ago). Included in the strata dated 32,000 years old were fragments of pottery and rock art figures.

Not only did this find challenge the cherished view that the first people to visit the Americas came across the land bridge from Asia into North America 13,000 years ago and then populated the Americas; it blew it out of the water by 20,000 years! And in South America! And discovered by a woman!

Even more shocking was the level of sophistication of the very early explorers, with pottery and art. Its location on the east side of Brazil was also troubling. If the first people in the Americas came across the Bering Strait, getting to eastern Brazil would mean a sea journey of 10,000 miles down the west coast of the Americas, followed by an incredibly difficult overland journey of thousands more to reach the Pedra Furada sites. Even some Clovis-Firsters thought it seemed far more plausible that the early explorers in Brazil came from Africa, making a trans-Atlantic journey of about 2000 miles, with both currents and wind in their favor. (In 2012, Katie Spotz, a 22-year old woman, rowed her way from West Africa to South America, solo, in 70 days.)

More recent finds at the Meadowcroft Rock Shelter in Pennsylvania have been dated to 14,250 years ago, pre-dating the Clovis sites by a thousand years. Other ancient sites in Delaware and Virginia have again raised the possibility that ancient explorers crossed the Atlantic Ocean long before Leif Erickson and Saint Brendan did.

The problem, it seems to me, is underestimating both the intelligence and the navigational skill of the ancient explorers.

Amazing explorers

Homo floresiensis, the “Hobbit” people whose remains were found on Flores Island in eastern Indonesia, lived from 94,000 to 12,000 years ago. The oldest bone fragment unearthed at the dig site was dated to 74,000 years ago. People settled in Australia at least 45,000 years ago, though some claim the date is more than 60,000 years ago. In order to reach these places, even with the ocean levels much lower than they are today, people needed to use boats.

Ancient Polynesian navigators, the greatest open ocean explorers in the world, found their way from Indonesia and New Guinea out into the Pacific Ocean, covering an area larger than North and South America combined, including Fiji, Hawaii, and Easter Island. (DNA studies have shown the Easter Islanders to be Polynesian.) It’s 4,610 miles from Fiji to Easter Island. Many believe that the Polynesians went on from Easter Island to explore the west coast of South America, (only 2,400 miles farther) bringing chickens from Asia to the New World and taking sweet potatoes back with them to Easter Island and Polynesia.

When European explorers arrived in Polynesia, they were amazed that the native mariners regularly sailed far out of sight of land and returned safely, maintaining a wide-area trade system that linked over a hundred islands, all without use of maps, compass, or sextant.

When European explorers arrived in Polynesia, they were amazed that the native mariners regularly sailed far out of sight of land and returned safely, maintaining a wide-area trade system that linked over a hundred islands, all without use of maps, compass, or sextant.

Later colonizers refused to believe these “savages” could be so skillful, dismissing their claims as fiction. In the 20th century, when the old ways of the navigator had almost disappeared, some Western sailors decided to learn the ways of the native navigators. The most famous was David Lewis, an accomplished sailor whose book We, the Navigators: The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific became the best source of information on the fading art of the South Pacific navigator. The 13,000 miles he sailed with native navigators in the South Pacific showed him how amazingly accurate their methods were. On some of the early voyages, he kept a compass and charts locked away in case he needed them. He didn’t.

Steering by the Stars

A traditional Polynesian navigator needs to know the night sky so well that he can mentally see the whole sky even if most of it is obscured by clouds. (I’m using he because all of the traditional Polynesian navigators still alive are male, and instruction in the art is now limited to males. However, ancient pictographs of Polynesian explorers show men, women, and children on board, in addition to lots of plants, even trees, and animals.)

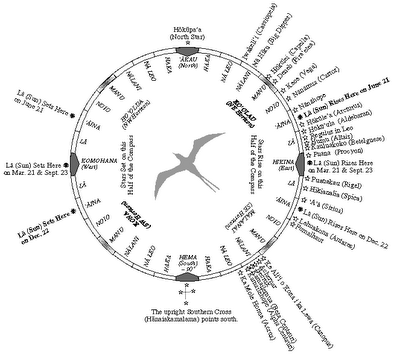

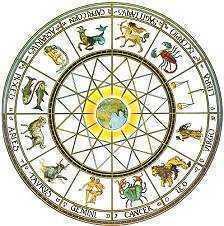

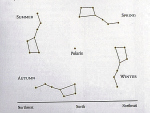

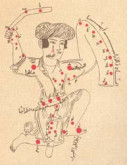

He needs to memorize the exact path, including rising and setting points, of at least 36 major stars and over a hundred secondary ones. For example, some stars rise in the east, such as Altair, the brightest star in our constellation Aquila the Eagle, and arc toward the north, so they can be used as reliable indicat ors of east only for a short time after they rise, a period usually measured in fists. The navigator holds out his arm so his fist lies between the horizon and the star he’s using. He knows this particular star is only reliable until it reaches two fists above the horizon. After that, he needs a new star to take him to the east. It might be a new star rising in the east or a star like Spica, which sets directly west. Navigators who travel to particular islands regularly know a sequence of stars to follow to each destination. The star compass pictured includes many of the stars navigators would know though they were known by different names in different areas. This knowledge was carried in the navigator’s memory, not on paper.

ors of east only for a short time after they rise, a period usually measured in fists. The navigator holds out his arm so his fist lies between the horizon and the star he’s using. He knows this particular star is only reliable until it reaches two fists above the horizon. After that, he needs a new star to take him to the east. It might be a new star rising in the east or a star like Spica, which sets directly west. Navigators who travel to particular islands regularly know a sequence of stars to follow to each destination. The star compass pictured includes many of the stars navigators would know though they were known by different names in different areas. This knowledge was carried in the navigator’s memory, not on paper.

If the eastern part of the sky is obscured by clouds, he must be able to use whatever part of the sky he can see to give him the orientation he needs to fill in the rest of the sky. Absolutely accurately.

Currents

He also needs to read the pattern and direction of the waves passing under the flexible hulls of his boat. Ocean currents in Polynesia tend to be very consistent. As the long waves pass under the boat at a consistent angle, the navigator knows where the currents are coming from and judges his direction accordingly. He knows that the currents bend and shorten as they near land. If storms are coming in, the surface currents will be different from the deeper currents. In some cases, he has six or seven different currents to track. Some navigators lie down on the deck or the outrigger to get an exact reading of the multiple currents.

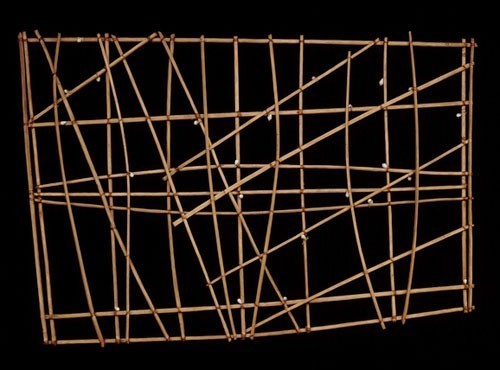

The stick chart pictured shows the currents in a particular area. Islands are marked with shells. While navigators sometimes studied charts like this before a voyage, they were not typically brought along on the boat. Few navigators explained the charts to outsiders.

The stick chart pictured shows the currents in a particular area. Islands are marked with shells. While navigators sometimes studied charts like this before a voyage, they were not typically brought along on the boat. Few navigators explained the charts to outsiders.

Birds, Vegetation Mats, Clouds, Colors, Smells

The traditional navigator knows that while certain birds are trans-oceanic flyers, like the albatross, others serve as good indicators of nearby land. Terns and noddies fly out from land in the morning and return at night. Frigate birds released from their cages are another good indicator of land. Since the birds will drown if they get their wings wet, they will either fly toward nearby land or head back to the boat.

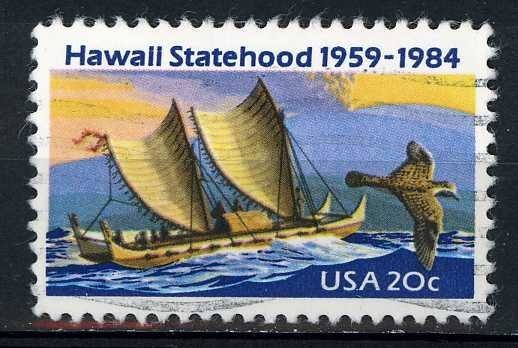

The migration of the Pacific golden plover was said to inspire the ancient Polynesians in Tahiti to look for the land the plovers were heading toward, which turned out to be the Hawaiian Islands. Later, Captain Cook also used the migration of the plover as an indication that land lay to the north, which is how he found Hawaii in the middle of the ocean. The golden plover, kolea, appears on the Hawaii state stamp (pictured) and on petroglyphs on Hawaii (illustration).

The migration of the Pacific golden plover was said to inspire the ancient Polynesians in Tahiti to look for the land the plovers were heading toward, which turned out to be the Hawaiian Islands. Later, Captain Cook also used the migration of the plover as an indication that land lay to the north, which is how he found Hawaii in the middle of the ocean. The golden plover, kolea, appears on the Hawaii state stamp (pictured) and on petroglyphs on Hawaii (illustration).

Mats of vegetation are also reliable indications that land is fairly close. Farther away, the mats break up due to wave action. The navigator looks to the clouds for information on wind velocity and approaching weather. In addition, clouds tend to form over land due to transpiration, so a lone cloud on the horizon might indicate an island lies beneath it. Sky color is also important, as is the color of the water, paler over reefs or submerged islands, darker in very deep sections.

A traditional Polynesian navigator had to use his entire body as a sensor. It’s no wonder the ancients respected him.

A Polynesian Network

Upon discovering the remains of a reed boat and wild sweet potatoes on Easter Island, Thor Heyerdahl theorized that South Americans drifted with the western current to Easter Island, bringing both the boat and the sweet potato with them, then later drifted all the way to Polynesia. While this theory has since been discarded, it may be partially correct. If the Polynesians went east all the way to South America, they may well have made the round-trip, bringing chickens to South America and the sweet potato to Easter Island.

Another fascinating hint at a Polynesian network comes from a Peruvian mummy examined by the University of York’s Mummy Research Group. They found it had been embalmed with the resin of the Araucaria conifer, closely related to the Monkey Puzzle Tree found in New Guinea.

The Importance of the Sea Explorer Community

Exploration by sea may have played a very important role in the development of human society. It necessitated an exact and widespread language, a desire to act together for the common good, advanced tool use, engineering skill, and extensive knowledge of the natural environment. It would have been driven by a need for constant innovation: stronger, flexible hulls, a more complete star map, different sail, hull, and paddle designs, double masts, outriggers. Knowledge was power. The person who could take a boat out of sight of land and return again was recognized as special. The person who could manage the same feat by night was very special. If he could manage a voyage of many days and nights between distant islands, he was extraordinary. Sea exploration created a society made of an accepted leader and his followers. The navigator’s word was law, just as it is today onboard a ship. Once the explorers formed a settlement in the new land, it would have been natural to maintain this social order, at least until populations grew and resources became scarce.

The ancient navigators faced a world ready to kill them if they were stupid or careless, maybe even if they weren’t. They accepted life that way. Sometimes I think it’s sad that so many people hunger for that kind of adventure today and find it only inside a video game.

Sources and interesting reading:

Guidon, N. and B. Arnaud. “The chronology of the New World: Two Faces of One Reality,” Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences, Sociales, Paris

Guidon, N. and Delbrios, G. 1986 “Carbon 14 dates point to man in Americas 32,000 years ago,” Nature, 321:769-771.

Gladwin, Thomas. East Is a Big Bird: Navigation and Logic on Puluwat Atoll. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1970.

“Homo Floresiensis,” Wikipedia

Lagan, Jack. The Barefoot Navigator: Navigating with the skills of the ancients. Dobbs Ferry, New York: Sheridan House, 2005.

Lewis, David. We, the Navigators: The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific, second edition. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994 (an excellent source)

“Monte Verde,” Wikipedia

“New Evidence from Earliest Known Human Settlement in the Americas,” Science Daily. www.sciencedaily.com

“Pedra Furada, Brazil: Paleoindians, Painting, and Paradoxes,” Athena Review, vol. 3, no. 2: Peopling of the Americas. www.athenapub.com/10furad.htm.

“Pedra Furada sites, (Piaui, Brazil)” by George Weber, www.andaman.org/BOOK/chapter 54

“Polynesian Discovery,” History channel, available on YouTube

“Sailing by the Stars – How the Ancients Did It” sailboat2adventure.com.blogspot.com

Schmitz, P. I. 1987. “Prehistoric hunters and gatherers of Brazil.” Journal of World Prehistory, 1:53 – 126.

May 18, 2012

Horoscopes

Many people today are pessimistic about the future. They listen to dire newscasts and worry about apocalyptic predictions ranging from Y2K to Armageddon to the end of the 13th baktun in the Mayan calendar.

But they’re always curious about their personal, immediate future. That’s why the girl in love picks the petals off a daisy, muttering “He loves me. He loves me not. He loves me. He loves me not,” picking off the petals one by one until she comes up with the answer.

And they read their horoscopes. Even folks who don’t believe in horoscopes glance at them in newspapers or magazines. Usually, the language is as vague as the note in a fortune cookie, with a message like “Hard work and perseverance will pay big rewards.” Still, they’re very popular.

Horoscopes have a very, very long history. They’re based on the assumption that all parts of the natural world are connected. Specifically, you are influenced by everything around you, including the sun, moon, stars and planets. In western astrology, your daily horoscope is based on the angles (“aspects”) of the sun, moon, and planets, as well as their placement in the sky. Your “sign” refers to the sun’s position in the ecliptic on the day you were born. The ecliptic is the path the sun takes across the sky over the course of a year. If you could superimpose the sun’s path on the night sky, it would move through the twelve constellations we call the Zodiac: Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces.

While some people dismiss modern astrology as nonsense, it may well have been the impetus for early humans to develop advanced counting systems, directional orientation, sophisticated language, and mathematics.

The Moon

For ancient people, the heavens provided a way to understand space and time. According to the NASA Lunar Science Institute, etched bones tracking lunar cycles date to at least 36,000 years ago (Lebombo bone found in Africa (photo), Aurignacian bone in Europe). After the sequence of day and night, the moon cycle offered the mostly easily understood division of time. Every moon followed the same pattern, taking the same number of days to wax and wane. It was predictable in the same way as day and night. Yet each moon was also connected to a slightly different season. It had its own name and activities.

cycle offered the mostly easily understood division of time. Every moon followed the same pattern, taking the same number of days to wax and wane. It was predictable in the same way as day and night. Yet each moon was also connected to a slightly different season. It had its own name and activities.

People near the sea probably knew that the moon influenced the tides. During the full moon or new moon, they saw the high tide was higher, the low tide lower. During quarter phases, the tides were weaker. And it was obvious that a woman’s menstrual cycle followed the same general timing as the moon, which is perhaps why the moon was often described as female. Clearly, the heavens influenced what happened on earth in profound and very personal ways.

They could see that the stars too moved in a predictable fashion. The constellations that revolved around the center of the sky were always there, while those closer to the horizon appeared at a certain season and then later disappeared off the opposite horizon.

Their appearance, disappearance, and reappearance coincided with specific seasons. They created the calendar.

Sirius, the “Dog Star” in Canis Major

For example, the first day that Sirius, the very bright star to the lower left  of Orion (shown in diagram), appeared in the pre-dawn sky in the east was considered the beginning of the year for the ancient Egyptians because it marked the time the Nile would flood, bringing its life-giving waters to the parched area.

of Orion (shown in diagram), appeared in the pre-dawn sky in the east was considered the beginning of the year for the ancient Egyptians because it marked the time the Nile would flood, bringing its life-giving waters to the parched area.

The ancients needed to know when the Nile would flood, so they needed to be able to count the days and record the information. This necessitated both advanced counting and consistent record-keeping, to allow them to learn that it would be about 365 days between one instance of Sirius rising, bringing the floods, and the next. Sirius, which they called Sopdet, came to be associated with the goddess Isis, wife of Osiris and mother of Horus, the falcon-headed god. In ancient stories, the 70-day absence of Sirius from the sky was the time Osiris spent in the Underworld after he was murdered. As Isis wept for him, her tears flooded the Nile. Using her magic, she was able to collect the parts of Osiris’ body and restore him to life. Of course, the flooding of the Nile also restored life to the area, and the celebration of the death and rebirth of Osiris became linked to the pre-dawn rising of Sirius and the annual regeneration of the parched earth along the banks of the Nile.

For the ancient Greeks, the pre-dawn appearance of Sirius marked the beginning of the hot, dry summer. Since they called it the Dog Star, they called the stifling hot days that followed its appearance the “Dog Days of summer.” They found its appearance a bad omen, bringing on strange behavior in those under the star’s influence, a condition they called “star-struck.”

For the ancient Maori, the pre-dawn appearance of Sirius marked the beginning of winter. One term for the star, Takurua, also meant winter.

Very early on, people realized that with enough effort, this sacred union of heaven and earth that moved time in cycles could be understood. More importantly, if humans wanted to be part of this time, they needed to participate in the drama being played out in the sky.

Venus – The Morning and Evening Star

Many ancient people believed each day was a separate entity, defined by the combination of celestial forces at work on it. For the Maya, one of the most powerful forces was Venus, the Morning and Evening Star. They knew this “wandering star” appeared as the Evening Star just after sunset in the west for about 263 days and then sank into the Underworld for about 8 days before being reborn in the east as the Morning Star, just before dawn. It stayed in the east for about 263 days then sank into the Underworld for about 50 days before reappearing in the west as the Evening Star. The whole cycle took 584 days. Five Venus cycles equals eight solar years, or 2,920 days.

powerful forces was Venus, the Morning and Evening Star. They knew this “wandering star” appeared as the Evening Star just after sunset in the west for about 263 days and then sank into the Underworld for about 8 days before being reborn in the east as the Morning Star, just before dawn. It stayed in the east for about 263 days then sank into the Underworld for about 50 days before reappearing in the west as the Evening Star. The whole cycle took 584 days. Five Venus cycles equals eight solar years, or 2,920 days.

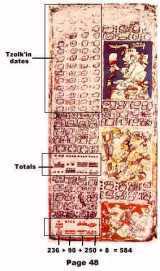

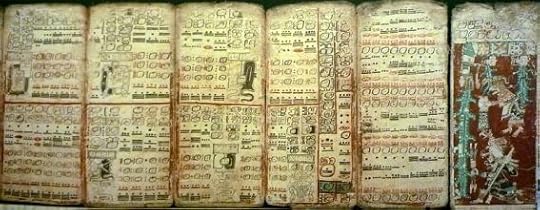

The Dresden Codex, one of the few Mayan screen-fold books to escape burning by Bishop de Landa, dedicates six pages to notations of the appearance of Venus as both Morning and Evening Star, covering five full cycles or 2920 days.

The rising of Venus as the Morning Star was a very dangerous time. Its light could bring evil down on those who looked at it. In addition, it was often the first day of warfare with another Maya city-state. The original “Star Wars.”

Lunar Eclipses

The Dresden Codex also follows solar and lunar cycles through 405 lunar months, for a total of 11,959 days. Both the lunar eclipse glyph and the solar eclipse glyph are visible in the pages in the photo (shown). They have a light half and a dark half, suspended from a sky band. A k’in (day) sign is superimposed on the two halves. In some, a serpent rises from below, mouth agape.

The tables in the Dresden Codex are extraordinary records, requiring the collective efforts of many people over a long period of time. These astronomers followed in the foosteps of many others who had recorded their observations. Some of the oldest human records note celestial events. It wasn’t idle curiosity that drove these people. It was a desire to be active participants in the sacred world the gods established.

Harmony of the Spheres

The famous Greek mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras (580 BC) felt the sun, moon, and stars generated unique sounds that blended into what he called the Harmony of the Spheres. This sound was echoed in all life on earth.

This idea that human and celestial time are intimately connected wasn’t limited to the ancients. Johannes Kepler, the noted German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer, explored the same concept in his treatise Harmonices  Mundi (1619), in which he stated that the regular pattern of the movements of the sun and planets reflected the glory of God. The unique combination of planets and stars at a given moment created a special harmonic vibration that was then taken up by all the creatures under their influence. This reflected the Hermetic maxim: “That which is Below corresponds to that which is Above, and that which is Above corresponds to that which is Below.” Today, however, Kepler is more likely referenced for his discovery of the Laws of Planetary Motion and his ability to predict the motion of the planets far into the future.

Mundi (1619), in which he stated that the regular pattern of the movements of the sun and planets reflected the glory of God. The unique combination of planets and stars at a given moment created a special harmonic vibration that was then taken up by all the creatures under their influence. This reflected the Hermetic maxim: “That which is Below corresponds to that which is Above, and that which is Above corresponds to that which is Below.” Today, however, Kepler is more likely referenced for his discovery of the Laws of Planetary Motion and his ability to predict the motion of the planets far into the future.

That’s exactly what the ancients wanted to do – to claim the future as part of their own time by extending their understanding far beyond the present. That quest demanded a uniform method of investigation, an exact method of counting and recording, a figuring of recurrent patterns, and a desire to share accumulated knowledge.

In our disenchanted age, where too much information is the norm and most of it is suspect, the daily horoscope survives as the distant echo of the time when people knew as surely as they were breathing that the alignment of the sun, moon, stars, and planets influenced all life on earth.

Sources and interesting reading:

Michael John Finney “The Dresden Codex: Eclipse Table” and The Dresden Codex: Venus Table” www.bibliotecapleyades.net

Maya Astronomy Page www.michielb.n/maya/venus

The Dresden Codex: The Book of Mayan Astonomy by Vladimir Bohm www.wolny.cz/paib/dresden_codex

NASA Ames Research Center “Johannes Kepler” kepler.nasa.gov/Mission/JohannesKepler

“Isis” and “Sirius” Wikipedia

Will Kyselka The Hawaiian Journal of History vol. 27 (1993)

April 8, 2012

Games

When we think of ancient people, we usually picture them hunting big game, gathering plants, making clothing and shelter, warding off terrifying beasts, fighting enemies, dealing with drought, flood, storms, injuries, and disease – in other words, struggling to survive.

However, studies of contemporary societies and recent archaeological finds paint a different picture. For contemporary hunter-gatherers, at least in the 20th century, collecting food, even in a challenging environment, took only half the day. Thousands of years ago, the job might have been even easier because there were far fewer people competing for available resources. Ancient people in temperate environments may well have spent far less time working each day than modern folks do.

So what did ancient people do with all that spare time? Apparently, some of them did exactly what we do: they played games.

Games played by individuals

Individual contests have probably been around since people have. It’s natural for us to want to know who can fight the best, run the fastest, or jump the highest. Winners gain power and prestige; losers are shamed.

However, physical contests can also prove deadly. The invention of the game allowed people to co mpete without having to die for the victory. It provided a format in which two individuals could struggle for dominance, but it also established a stopping point and rules about what was allowed and what was forbidden.

mpete without having to die for the victory. It provided a format in which two individuals could struggle for dominance, but it also established a stopping point and rules about what was allowed and what was forbidden.

Wrestling is the oldest individual competition with documented rules. A papyrus discovered in Egypt but written in Greek, dated to 100 AD, states the rules of the game at that time. It’s also represented in a sort of ancient animation sequence in an Egyptian mural that is 4000 years old (shown).

War games

Settling disputes without having to kill a lot of people was also important in early warfare. In some cases, rather than have opposing armies battle each other with tremendous loss of life on both sides, the outcome was decided by a battle of champions. Each side picked the person most likely to win the fight (usually the biggest and strongest) to represent them. Once the contest was won, everyone could go home, except of course for the champion who lost. One of the most famous battles of champions is recalled in the Bible story of David and Goliath. Goliath, the champion of the Philistines, was a mighty giant whose challenge to the Israelites’ army went unanswered until David volunteered. In an early example of brain vs. brawn, David won the contest with the help of a few well-aimed stones from his sling. Once Goliath was defeated, David cut off his head and displayed it to the enemy forces, at which point they retreated. Thus, a conflict that might have killed many men was settled by two individuals. In this case, war imitated a game. There were rules and limits.

life on both sides, the outcome was decided by a battle of champions. Each side picked the person most likely to win the fight (usually the biggest and strongest) to represent them. Once the contest was won, everyone could go home, except of course for the champion who lost. One of the most famous battles of champions is recalled in the Bible story of David and Goliath. Goliath, the champion of the Philistines, was a mighty giant whose challenge to the Israelites’ army went unanswered until David volunteered. In an early example of brain vs. brawn, David won the contest with the help of a few well-aimed stones from his sling. Once Goliath was defeated, David cut off his head and displayed it to the enemy forces, at which point they retreated. Thus, a conflict that might have killed many men was settled by two individuals. In this case, war imitated a game. There were rules and limits.

Some Plains Indian tribes used the practice of counting coup for the same end. They would strike the enemy in the head with a hand or a coup stick, which counted as a kill in terms of pride and power but didn’t actually kill the loser. This was particularly important when human population density was low and the hunters were needed to feed the rest of the people. In some cases, the impression of victory was enough to settle the dispute.

Team games

A team competition is very different from an individual contest. In a team, the individual’s drive to win is subsumed to the collective success of the group. The great team player  is one that makes sure the team wins, even if it sometimes means less personal glory.

is one that makes sure the team wins, even if it sometimes means less personal glory.

Once a player dons the uniform of a famous team, he takes to himself part of that past glory. He becomes more than he was alone. As the Liverpool Football Club logo says, “You’ll never walk alone.”

The team creates a tribal identity for both players and supporters. The team’s success directly affects the tribe it represents. Team competition is ritualized warfare by a group of champions (in the old sense of the word) specifically chosen to represent the larger community in battle.  People today proudly wear the colors of the team they support, like the yellow and blue of the Brazilian soccer team in the photo, fly team flags outside their homes, even paint their faces to display their allegiance to that group, all of which are clear echoes of ancient practices. Allegiance to a particular team can be so ingrained that a long-time New York Yankees fan might find it hard to support the San Francisco Giants, even after moving to California.

People today proudly wear the colors of the team they support, like the yellow and blue of the Brazilian soccer team in the photo, fly team flags outside their homes, even paint their faces to display their allegiance to that group, all of which are clear echoes of ancient practices. Allegiance to a particular team can be so ingrained that a long-time New York Yankees fan might find it hard to support the San Francisco Giants, even after moving to California.

While a win is cause for celebration among all of the team’s supporters, a loss is a bitter disappointment. True, we don’t sacrifice the losers on the ballcourt the way some Mesoamericans did, but a loss is still painful. In some soccer matches, the loss of an important game can bring death threats to the players involved and bloody, sometimes fatal fights among the fans. In these cases, the failure of the team is a personal disgrace.

Political connections

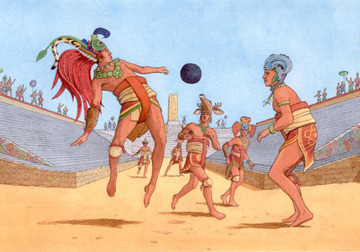

The spectacle of organized large-scale games can also reinforce political power. The oldest documented tea m sport is the Mesoamerican ballgame. At least 3,500 years old, it was often used as a symbol of cultural identity and political power, with rulers of powerful city-states frequently appearing on monuments in the garb of a ball player, sometimes combined with images of the gods. That’s not surprising. According to Maya creation stories, the Hero Twins had to face many ord

m sport is the Mesoamerican ballgame. At least 3,500 years old, it was often used as a symbol of cultural identity and political power, with rulers of powerful city-states frequently appearing on monuments in the garb of a ball player, sometimes combined with images of the gods. That’s not surprising. According to Maya creation stories, the Hero Twins had to face many ord eals before they played ball against the Lords of the Dead. The contest was long and complicated, involving many personal tests and the use of the head of one Twin as a ball in the game. Like their father, they had to die before they could be reborn. The game is therefore intimately connected with death and rebirth, especially that of the maize seed that must be buried in the earth before it can be reborn into the life-sustaining plant. It’s easy to see why the Maya kings wanted to be connected to the ballgame. The first illustration is an artist’s conception of the ancient game in play. The other is taken from a vase commemorating the visit of a neighboring ruler, showing him dressed as a ballplayer. While his garb is impressive, it’s not really suited to playing the game. It’s the symbolism that counts.

eals before they played ball against the Lords of the Dead. The contest was long and complicated, involving many personal tests and the use of the head of one Twin as a ball in the game. Like their father, they had to die before they could be reborn. The game is therefore intimately connected with death and rebirth, especially that of the maize seed that must be buried in the earth before it can be reborn into the life-sustaining plant. It’s easy to see why the Maya kings wanted to be connected to the ballgame. The first illustration is an artist’s conception of the ancient game in play. The other is taken from a vase commemorating the visit of a neighboring ruler, showing him dressed as a ballplayer. While his garb is impressive, it’s not really suited to playing the game. It’s the symbolism that counts.

The ancient Romans were famous for their games at the Coliseum, which could involve fights with or betw een wild animals, gladiatorial combat (shown), comical farces, even capital punishment (or reprieve), all with free lunch and wine courtesy of the Emperor. The observers certainly understood who was providing the show. In 76 BC, Julius Caesar organized a naval battle show that involved a specially-dug lake, over a hundred ships, and thousands of men. The spectacle reinforced the image of the Empire’s power in the minds of the spectators. It was entertaining but also a little scary.

een wild animals, gladiatorial combat (shown), comical farces, even capital punishment (or reprieve), all with free lunch and wine courtesy of the Emperor. The observers certainly understood who was providing the show. In 76 BC, Julius Caesar organized a naval battle show that involved a specially-dug lake, over a hundred ships, and thousands of men. The spectacle reinforced the image of the Empire’s power in the minds of the spectators. It was entertaining but also a little scary.

It’s interesting that all major US football, soccer, basketball, baseball, and hockey games begin with the singing of the national anthem, a practice that began during World War II. However, individual sports events such as golf and tennis do not. Is that because the team competition is related to the larger team – the nation? Is it a subtle reminder of who is bringing you this afternoon of sport?

The board game: a race or a war

Not all games involve physical activity. Some are virtual competitions played out on a board with pieces representing the players. The most common form is the race game, in which the player who gets to the end point first wins. You might recognize the race in a modern game like Candy Land or an more ancient game like backgammon or parcheesi (based on the Indian game pachisi).

Another common form is the fight game, where the goal is the annihilation of the opponent through strength and strategy. It appears in modern games like Risk and more ancient games like chess or checkers. It’s also the core of popular video games like World of Warcraft, Halo, Call of Duty, Deus Ex, etc.

According to “Games People Played,” an article in the May/June issue of Archaeology magazine, archaeologists working at the Tlacuachero site in southern Mexico (occupied over 5,000 years ago) were puzzled by groups of tiny holes in an oval pattern clustered in one section of the site. A possible answer was suggested by a 1907 book called Games of the North American Indians by Stewart Colin. Across Canada, the United States, and Mexico, Colin collected accounts of indigenous peoples’ board games, all of which were either race or war games. The Hualapai people of Arizona used a game board closely resembling the one at Tlacuachero. Players tossed pieces of wood flattened on one side and smooth on the other to determine how many places they could move their stone or shell pieces. The winner was the first player to move all the pieces to the finish.

Game boards have been found in ancient Mesoamerican sites from Teotihuacan (northeast of Mexico City) to Copan (Honduras). Of course, many other games might have been played without leaving a wood or stone board behind for archaeologists to find. A race game could be played with nothing more than pebbles and holes in the sand. A war game like marbles would leave no recognizable clues behind.

Mancala/Oware

If the game board was rectangular instead of spiral, the Tlacuachero game would look very similar to mancala (known by many other names, including Kalah and Oware), developed from an African count and capture war game that some suggest is well over 7000 years old.

Senet

Another ancient board game is Senet, shown in the picture being played by Nefetari, one of the Great Royal Wives of the pharoah Ramses the Great, about 3500 years ago.

Another ancient board game is Senet, shown in the picture being played by Nefetari, one of the Great Royal Wives of the pharoah Ramses the Great, about 3500 years ago.

Unfortunately, no one has found any record of the rules of the game.

Checkers

Played on a board similar to the modern one, checkers also shows up in ancient Egypt.

The Royal Game of Ur

This board game, popular in Ur (Iraq) at least 5000 years ago, worked as both a race game and a divinatory tool. Each player had five pieces; moves were determined by a throw of knuckle bones or cowry shells. Certain squares, which apparently had astronomical connections, portended good fortune if landed on. Several very ornate boards have been found, the most famous of which is currently in the British Museum’s collection in London (shown in photo).

This board game, popular in Ur (Iraq) at least 5000 years ago, worked as both a race game and a divinatory tool. Each player had five pieces; moves were determined by a throw of knuckle bones or cowry shells. Certain squares, which apparently had astronomical connections, portended good fortune if landed on. Several very ornate boards have been found, the most famous of which is currently in the British Museum’s collection in London (shown in photo).

Backgammon

This race game, which originated in Persia (Iran)more than 4,500 years ago, has survived to this day in much the same form. It’s worth noting that the oldest backgammon board was found at a mysterious and wonderful ancient city called Shahr-e Sukteh (Iran). The fields on the game board were made to resemble the coils of a great snake. (Another interesting though unrelated find at this site was the first artificial eyeball, a round object covered in gold foil. Tiny holes in the sides allowed the eyeball to be threaded and then sewn to the eyesocket. The wearer was a six-foot tall woman, whose remains were dated to 4,800 years ago. The site also included a skull with signs of brain surgery and the oldest known dice.)

Chess

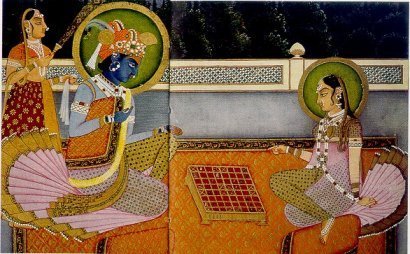

The undisputed king of board games, often called the game of kings, is chess, the ultimate war game. It has many variations and multiple historical sources, including India, China, and Persia. In the illustration, Radha and Krishna play a game called chaturanga, a precussor of chess which gave different powers to different pieces. According to a story told by Stewart Gordon in his article “The Game of Kings,” Persian nobles first learned the game from a visiting Indian emissary. Completely taken with the game, they practiced non-stop for days and then beat him! In the list of ancient games, though, it is a relative newcomer, at only 2000 years old.

The undisputed king of board games, often called the game of kings, is chess, the ultimate war game. It has many variations and multiple historical sources, including India, China, and Persia. In the illustration, Radha and Krishna play a game called chaturanga, a precussor of chess which gave different powers to different pieces. According to a story told by Stewart Gordon in his article “The Game of Kings,” Persian nobles first learned the game from a visiting Indian emissary. Completely taken with the game, they practiced non-stop for days and then beat him! In the list of ancient games, though, it is a relative newcomer, at only 2000 years old.

What is the value of games?

A game is a controlled competition. Like counting coup, it allows the opponents to compete with a clear sense of what constitutes winning. A board game is a virtual competition with minimal risk (though I’ve seen more than one relationship end over Monopoly games).

Team games create tribal connections. We are, at least for that moment, united with others in support of a common goal.

When we play a game of football or chess, or we cheer on our favorite team, we are carrying on a very, very old tradition.

Sources and interesting reading:

The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame, by Michael Whittington, published by Thames and Hudson, 2001

“The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame” http://www.ballgame.org

Artist’s rendering of the Mesoamerican ballgame, from the Majorie Barrick Museum, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

“The Royal Game of Ur” http://www.gamecabinet.com/history/Ur

“Big Game Hunter,” Time Magazine, June 19, 2008

“Board Game” Wikipedia

“Games Ancient People Played” by Barbara Voorheis, Archaeology magazine, May/June, 2012

“Shahr-e Sukteh” Wikipedia

“Ancient text proves wrestling is oldest sport on record,” by Gary Mihoces, USA Today, October 11, 2011

“The Game of Kings,” by Stewart Gordon, Saudi Aramco World, July/August, 2009

February 22, 2012

Blog party for Alex J. Cavanaugh’s new book

The Misfits and Heroes blog is happy to be part of the book launch party for Cassa Fire, the sequel to Alex J. Cavanaugh’s sci-fi adventure Cassa Star, which was an Amazon top-ten bestseller. You can learn more about the books and the author at his blog at http://alexjcavanaugh.blogspot.com/

The blog tour goes from February 28 to March 9. If you comment on one of his blog posts within that period, you’re eligible to win copies of the books and other prizes. Check out his blog for all the details and the YouTube address for the video trailer:

http://www.youtube.com/embed/Qa6VINRGtyE

Guest post on J.C. Martin’s blog

Check J.C. Martin’s interesting blog for the Misfits and Heroes giveaway and guest blog post.

Check J.C. Martin’s interesting blog for the Misfits and Heroes giveaway and guest blog post.

http://jc-martin.com/fighterwriter/2012/02/wy-interview-kathleen-flanagan-rollins/

February 18, 2012

The Night Sky: Calendar, Compass, Culture

For some modern viewers, the sight of a sky full of stars is unnerving, making them feel small and insignificant. In “We’ve Got Tonight,” Bob Seger sings, “Why should we worry, no one will care, girl. Look at the stars, so far away/ we’ve got tonight, who needs tomorrow?” This makes a curious statement. Because the stars are so far away, what we do is irrelevant. No one will care if we spend the night together, just as the stars don’t care. Not much in the romance department.

Ancient people had a very different view. Their lives were inextricably linked to the stars and planets. The rising and falling of stars with the seasons, the appearance and disappearance of the planets determined what happened on earth. We see this as astrology, but the ancient people saw no difference between astrology and astronomy. They needed to understand the motion and patterns of the night sky because their lives were entwined with them. The stars weren’t distant at all. They were immediate and active.

Calendar

For the ancient peoples, the sun and moon provided easy measures of time. Every 29 days or so, the moon begins a new cycle of waxing from a slim crescent to a full moon and then waning back to the last crescent before it goes completely dark, only to start over again. Some modern people still use a calendar based on the cycles of the moon. The Chinese traditional calendar, the Islamic calendar, and the Jewish calendar are all lunar, with twelve months of 29 or 30 days. The Chinese calendar adds extra days as needed at the end of the year to correspond to the solar calendar. The Jewish calendar adds them every Leap Year.

For many ancient societies, each of the moons had a name, indicating a significant seasonal marker: New Rains Moon, Deep Frost Moon, etc.

By the stars’ position, people could identify which moon it was. Take the most identifiable aste rism in the night sky, The Big Dipper, which many ancient people saw as part of a celestial bird. In the early evening in January, the dipper seems to stand on its handle (or wing). By April, it lies upside down. By July, it seems to stand on the outside of the cup. In October, it lies right side up.

rism in the night sky, The Big Dipper, which many ancient people saw as part of a celestial bird. In the early evening in January, the dipper seems to stand on its handle (or wing). By April, it lies upside down. By July, it seems to stand on the outside of the cup. In October, it lies right side up.

Source: www.physics.ucla.edu

Compass

The pointer stars, the outside of the dipper’s cup, point to the North Star. You can find approximate north by sighting along any straight object aligned with the North Star. The opposite end of the same stick points south. Once those two are established, you can find east and west with only a little more work. As recently as the 1800’s, escaping slaves used the Big Dipper, “The Drinking Gourd,” as a guide to lead them to freedom in the north.

For those in the Southern Hemisphere, the Southern Cross serves the same purpose as a circumpolar asterism, but the pole itself is an empty space, sometimes referred to as a cave, unmarked by a star. This was the case in the Northern Hemisphere as well 10,000 years ago, when the center was between stars.

Night Clock

The Big Dipper appears to move in the course of the night, swinging around the unmoving center of the sky, the North Star. It would be easy for people to judge how late it was by how much the dipper had moved.

Culture

More importantly, for the ancient peoples, the night sky, especially the Milky Way, was a powerful, frightening force that was connected to all life on earth. It contained creation and death, darkness and light.

Seeing The Milky Way

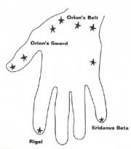

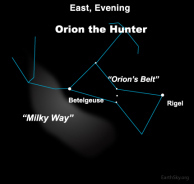

The Milky Way is the galaxy we live in. It contains, according to the Center for Astrophysics and Space Sciences at the University of California, San Diego, over 400 billion stars, including our sun. If you’re unfamiliar with the Milky Way, start with finding a familiar constellation like Orion (diagram). The Milky Way passes over the figure’s shoulder. You’ ll need a dark sky, away from sources of light pollution that will rob you of all but the brightest stars.

ll need a dark sky, away from sources of light pollution that will rob you of all but the brightest stars.

The three “belt” stars, the very bright shoulder star Betelgeuse, and the very bright “foot” star Rigel make this constellation easy to differentiate from others.

With some help from the Hubble telescope, you can see the rest of the story!

With some help from the Hubble telescope, you can see the rest of the story!

Source: httyp://hubblesite.org/gallery

(Photo source: Patrick’s Photoblog, vignette.com)

In the photo, look for the three stars of Orion’s belt and the bright smudge that is the Orion Nebula. The Milky Way rises almost vertically in the center of the photo.

The Milky Way looks like a river of bright stars flowing across the sky. The name comes from the ancient Greeks, who said it was milk from cows, with each star a cow, though the story was later changed to milk spilled by the goddess Hera, wife of Zeus, as she suckled Heracles. The confusion probably came from the ancient Egyptians, for whom the Milky Way was sacred cow’s milk of Hathor, a goddess who was often represented as a woman with a cow horn headdress, or a sacred cow. (See earlier post “The Eye in the Hand” for more on Hathor and Tanit.)

For the East Asians, it was the Silvery River of Heaven. For Finns, the Pathway of the Birds. For Hungarians, the Warriors’ Road. For many cultures, including the Maya, the dark rift within the white band was considered the Black Road, the Pathway of the Dead.

Linda Schele an d other prominent Mayanists have held that for the ancient Maya, the movement of the Milky Way in the night sky repeated their creation story. When it is vertical, it is the World Tree, first used by the creator gods to lift up the sky and separate it from the water. (See the dramatic Milky Way photo by Dyer.) As the night goes on, and a different section of the Milky Way becomes visible, the shape is interpreted as the Crocodile Tree, where the World Tree grows out of a crocodile’s back, and again later, when the Milky Way stretches horizontally across the sky, it is seen as the Celestial Canoe that carries the Paddler gods to the place of Creation, near Orion, where they set the first stone. The placing of the hearthstones and the lighting of the first fire began our time, the fourth age.

d other prominent Mayanists have held that for the ancient Maya, the movement of the Milky Way in the night sky repeated their creation story. When it is vertical, it is the World Tree, first used by the creator gods to lift up the sky and separate it from the water. (See the dramatic Milky Way photo by Dyer.) As the night goes on, and a different section of the Milky Way becomes visible, the shape is interpreted as the Crocodile Tree, where the World Tree grows out of a crocodile’s back, and again later, when the Milky Way stretches horizontally across the sky, it is seen as the Celestial Canoe that carries the Paddler gods to the place of Creation, near Orion, where they set the first stone. The placing of the hearthstones and the lighting of the first fire began our time, the fourth age.

The Dark Patches

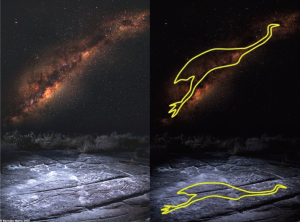

The Australian Aboriginal peoples see their creation stories in the Milky Way as well, but they deal more with the black areas of the Milky Way, what astronomers today refer to as dark dust clouds. If you have a really good sky for viewing, you can see these dark areas quite clearly. (In the stunning photo by John Gleason, you can understand how people could see shapes in the dark sections.)

According to Bill Yidumduma Harney, his Wardaman p eople see all their creation figures in the Milky Way. Even more, the important sites for viewing specific moments echo in the landscape the position of the important stars in the sky. At those special places, when the sky is in perfect harmony with the land, the Wardaman feel the sky is alive and star beings can easily go from one world to another. Note the carving of the emu on the rock that coincides with its appearance in the sky.

eople see all their creation figures in the Milky Way. Even more, the important sites for viewing specific moments echo in the landscape the position of the important stars in the sky. At those special places, when the sky is in perfect harmony with the land, the Wardaman feel the sky is alive and star beings can easily go from one world to another. Note the carving of the emu on the rock that coincides with its appearance in the sky.

(For a complete though not easy explanation of Wardaman cosmology as expressed in the night sky, see Dark Sparklers by Hugh Cairns and Bill Yidumdum Harney.)

The night sky – The World Tree, The Crocodile, The Emu, The Dolphin, The Paddler Gods, The Seat of Creation, The Birthplace of the Stars, The River of the Dead, The Black Dreaming Place, The Warrior Road, The Pathway of Birds – is still there, waiting to amaze you, to fill you with wonder. Find a dark spot on a clear night and let it become part of your world.

Sources and interesting reading:

“Creation, Cosmos, and the Imagery of Palenque and Copan,” by Linda Schele and Khristaan D. Villela, University of Texas, Austin

Maya Cosmology, www.authenticmaya.com/maya_cosmology

“2012 and the Milky Way Tree,” by Brian Keats, October 2009

A Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World, by Lynn V. Foster

“Beautiful Milky Way Photography,” in Paulo Gabriel’s blog, abduzeed.com

Professor Gene Smith’s Astronomu Tutorial: The Sturcture of the Milky Way,” University of California, San Diego, casswwwu.ucsd.edu

Tony Garone’s simulations of Maya Creation story superimposed on star maps, www.garone.net/maya

Patrick’s Photoblog, vignetted.com

Observatorio ARVAL, oarval.org

January 2, 2012

The Eye in the Hand

The Eye in the Hand

It’s curious how the past inhabits the present. The Eye in the Hand is a good example. It’s currently found in corporate logos, music promotions, edgy fashion, and scary movies like Pan’s Labyrinth, but the history of the symbol is complicated and global.

Perhaps the symbol works because it’s arresting. It combines two of our most powerful data receptors, but the two don’t belong together. It’s not possible to have an eye in a hand or to see through a hand, so the image conjures up something beyond normal life. In that sense, the Second Life logo, which features the eye in the hand, is very close to the historical roots of the symbol that is clearly connected to something beyond life.

It’s hard to talk about the eye in the hand without also considering The Evil Eye. While the ancient artifacts that include the eye in the hand don’t necessarily invoke a protective charm against the evil eye, the current charms certainly do. Currently, people have two popular choices in charms to ward off the Evil Eye: The Evil Eye charm or the Hamsa Hand.

The Evil Eye

The blue glass eye, known (rather confusingly) as The Lucky Eye or The Evil Eye, promises to protect the bearer from negative energy such as resentment or envy as well as general misfortune such as accidents and disease. The concept of the Evil Eye, the belief that others have the power to curse you by giving you a malevolent stare, is widespread in the Middle East, Africa, India, Central America, North America, South Asia, and Europe, especially the Mediterranean area. Damage from an evil eye can include withering, sickness, even death. Even those who don’t believe in the Evil Eye may refer to the concept in sayings like “She gave me the evil eye,” or “If looks could kill, I’d be dead now.”

Because the evil eye is generally thought to be blue, the charms that are meant to protect the bearer are usually blue as well.

The Hamsa Hand

The other popular protective talisman is the eye in the hand charm known as Hamsa (Arabic), Hamesh (Hebrew), Humsa (Hindu), Mano Ponderosa (Italian), or Helping Hand (hoodoo). In Jewish folk tradition, it is known as the Hand of Miriam (the sister of Moses). In some Muslim areas it is commonly called the Hand of Fatima (the daughter of Mohammed), despite Islam’s official ban on talismans. Some Catholic groups refer to it as the Hand of Mary (the mother of Jesus).

Hamsa hands come in a very wide variety of forms, some very male, some very female, some with five fingers, some with three fingers and two very small appendages, some with barely differentiated fingers. Some have a very large eye; others replace the eye with a circle or star. Some include other symbols in the fingers and palm. Most point down but some point up.

Hamsa hands come in a very wide variety of forms, some very male, some very female, some with five fingers, some with three fingers and two very small appendages, some with barely differentiated fingers. Some have a very large eye; others replace the eye with a circle or star. Some include other symbols in the fingers and palm. Most point down but some point up.

Origins

There is great debate over the origin of the Eye in Hand. Some say it comes from The White Tara, the Hindu representation of motherly protection and generosity who is often pictured with eyes in her forehead, hands, and feet. In some images, she holds the lotus of compassion in one hand.

Others connect the Hamsa to Hathor, the Egyptian Earth Mother, sometimes pictured as a woman wearing a red dress and a headdress of cow’s horns, other times as a cow with a sacred eye, other times as the Milky Way. The ancient Greeks morphed Hathor into Aphrodite; the Romans made her into Venus.

The Phoenicians used the hand of Tanit, a powerful female sky goddess, to ward off evil. A fierce warrior, she was sometimes depicted with the head of a lion. Tanit’s equivalents include Astarte (West Semitic), Anat (Mesopotamian), and Inana (Sumerian), all powerful females associated with love, fertility, and war.

The Female/Sky/Milky Way/Orion Connection

Since we seem to have a female, heavenly connection with Hathor, Tanit, and others, it’s interesting to note the Arabic origin of the named stars Betelgeuse, Rigel, and Belatrix, all in the constellation Orion.

Betelgeuse comes from yad al-jauza (mistranslated originally as bat al jauza) meaning “the hand of the Central One,” referring to a mysterious and powerful female entity who kneels in the night sky with the Milky Way at her shoulder(pictured). Rigel comes from the Arabic rijl al-jauza, meaning “the foot of the Central One.” Belatrix, another star in the constellation, means a fierce female warrior (which suited her character in the Harry Potter stories).

The New World

But the eye in hand symbol also has a New World history. If you look at the images associated with The Eye in Hand on your computer, you’ll come across several f rom pre-Columbian North America. The most famous is the engraved gorget (collar ornaments) from Moundville, Alabama, featuring a hand with an eye (pictured above). The hand is surrounded by two intertwined, knotted horned rattlesnakes. A similar piece, also from Moundville, includes the hand with the eye but leaves out the snakes and places the hand between a symbol of a cross inside concentric circles at the top and what looks like an earthen mound at the bottom (pictured).

rom pre-Columbian North America. The most famous is the engraved gorget (collar ornaments) from Moundville, Alabama, featuring a hand with an eye (pictured above). The hand is surrounded by two intertwined, knotted horned rattlesnakes. A similar piece, also from Moundville, includes the hand with the eye but leaves out the snakes and places the hand between a symbol of a cross inside concentric circles at the top and what looks like an earthen mound at the bottom (pictured).

The two Moundville gorgets shown in the illustrations are quite similar. Both have concentric circles at the top and a link to the eye in hand. However, the illustration from Vernon James Knight’s book Archaeology of the Moundville Chiefdom, detailing the finds of the 1905 excavation of the area, has a slightly different design inside the circles and omits the mound at the bottom.

Other pieces found in the southeastern US include the hand in the eye in different though related forms.

Although the designs on the Mississippian gorgets look similar to the modern-day Hamsa Hands, there is no indication that the North American pieces had the same function. Actually, it’s hard to know how the symbol functioned for those who wore it. Between 500 and 1500 AD, the Mississippian culture included trade-linked settlements that ranged from Wisconsin to the Gulf of Mexico, but after the arrival of the Europeans, many of the Mississippian settlements failed due to disease and warfare, and the flat-top mounds typical of their cities were destroyed by the settlers.

The Hand

However, many anthropologists now believe that The Hand constellation, made up of the lower half of Orion, was considered a portal to the Otherworld in Southeastern US cosmology. (See “Mississippian and Maya cosmology: The Hand constellation and the Milky Way” at anthro-lingblogspot.com/2010/01mississippian....) The stars that make up Orion’s belt formed the wrist (top) of the severed hand.

The Lakota and other Plains Indians also saw a star grouping they called The Hand in the bottom half of what we call Orion.

In researching some Mississippian sites, experts have suggested that marks on the palm of the hands symbolized points where the spirit may enter or leave the body.

The Serpents

The snakes in the Moundville pieces have been identified as tie snakes, horned serpents that play an important part in the oral history of tribes from the Great Lakes to the southeastern woodlands. These Great Serpents were powerful beings from the Underworld  who were in constant battle with the forces of the Upperworld, usually represented by the Thunderers, falcon-men. The combination of these two opposite forces resulted in the winged, horned serpents that wheeled around the center of the world in the swastika, powering the motion of the world through the energy of their opposition. (See earlier entry “The Flight of the Eagle, The Power of Symbol.”)

who were in constant battle with the forces of the Upperworld, usually represented by the Thunderers, falcon-men. The combination of these two opposite forces resulted in the winged, horned serpents that wheeled around the center of the world in the swastika, powering the motion of the world through the energy of their opposition. (See earlier entry “The Flight of the Eagle, The Power of Symbol.”)

The Eye in the Hand

According to the “Southeastern Ceremonial Complex” entry in Wikipedia, “The Hand and Eye Motif was common in Mississippian symbolism and may be related to the Ogee Motif, suggesting it represents a portal to the Otherworld.”

The Road across the Sky

For many ancient North American, Central American, and South American peoples, the Milky Way was the path the dead took to the Otherworld. The Maya saw the Milky Way as having four arms that spread out across the world. At the center of the Milky Way, the three hearthstones were placed at the moment of Creation. These three stones are part of the constellation we know as Orion and they became the portal through which the dead entered the Milky Way, the great river of stars that flows next to the hearthstones.

The Apache believed that Yolkai Nalin, the feared goddess of death and the afterlife, controlled the path of souls after death. The road to the Otherworld that we call the Milky Way passed over her shoulders.

So…

If we put all of these parts together, it seems fairly defensible that we have a Moundbuilder piece that makes reference to a Hand constellation that serves as a portal to the Otherworld, the boundary between this life and the beginning of the next life.

And it’s the logo for Second Life. Irony abounds.

It’s impossible to tell how much of the symbolism of the New World continues, overlaps, or reflects that of the Old World. Perhaps the two developed along parallel lines without ever intersecting. Perhaps not. Certainly, the modern Hamsa charm, which is most popular around the Mediterranean, bears an eerie resemblance to the ancient Moundbuilder gorget. Even more interesting is the invocation of the very powerful female figure (Mary, Fatima, Miriam) for protection. It’s hard not to see parallels between them and The Central One who guards the portal to the Otherworld and bears the Path of the Dead on her shoulder.

Interesting sources include

The First Maya Civilization: Ritual and Power before the Classic Period, by Francisco Estrada Bell

“Mississippian” bama.ua.edu/alaarch/prehistoricalabam...

“The Southern Cult, Southeast Ceremonial Complex” archaeology. about.com/od/sterms/southerncult.htm

“Southeastern Ceremonial Complex” in Wikipedia

“Mississippian Culture” in Wikipedia

“Mississipian and Maya Cosmology: The Hand Constellation and the Milky Way” http://anthro-lingblogspot.com/2010/01mississippianandmayacosmology

December 11, 2011

12 Days of Christmas Blog Tour

http://intoxicatedbybooks.blogspot.com/2011/10/12-days-of-christmas-blog-hop.html

Welcome to the Blog Hop!

Misfits and Heroes is participating in the 12 Days of Christmas Blog Tour set up by Intoxicated by Books. We’re giving away four copies of Misfits and Heroes: West from Africa and fifty handy notepads. All you have to do is leave your name and address in the Comments section. No, they won’t be sold or given away to anybody! Please add how you heard about the Misfits and Heroes blog. Thanks.

Misfits and Heroes: West from Africa is adventure/exploration/magic/spirit intervention. It was recently named one of Kirkus Reviews Best of 2011, one of only 51 independently published books to make the list and one of only four indie adventure novels.

http://www.linkytools.com/basic_linky_include.aspx?id=109862

The winners have been notified by email. The prizes should be in the mail tomorrow (Friday, December 30).

Thanks for your interest in the blog and the book!

Kathleen Rollins

November 14, 2011

Drawing a Line in the Sand: Where Art, Math, and Spirit Intersect

Perhaps the most interesting and universal art form is also the most ephemeral: drawings made on smoothed dirt. Many are based on common geometric forms: the circle, concentric circles or overlapping circles, and the circle bisected by perpendicular lines.

It can be argued that people have a universal fascination with geometric forms, especially the circle. The very oldest form of rock art all over the world is the cupule, a circular indentation engraved in a rock surface. While these cupules probably had many different meanings and functions in the society, the presence of these earliest forms of “making my mark” in the Americas, Africa, Australia,India, Europe, and the Pacific Islands is very interesting. They are also by far the most common form of

rock art, appearing in groups of hundreds, sometimes thousands in a single location. A Neanderthal burial site in Europe dated between 40,000 and 70,000 years ago includes a stone slab marked with sixteen cupules, most of them grouped in pairs.

The stone was placed over the body of the deceased teenage girl so that the sixteen marks faced toward her. Cupules in Australia have been found to be at least 60,000 years old; some experts put the date closer to 116,000 years ago. The record is a series of cupules found in a cave in India that experts claim are over 200,000 years old.

On the Big Island of Hawaii, a large grouping of cupules and concentric circles

fills an old lava field right next to one of the big tourist hotels. Perhaps it served the same function as the hotel’s register book. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to know how these forms functioned in the societies that left them behind. There are records of relatively modern practices that involved these cupules, but there is no guarantee that these practices were similar to those used long ago.

What we can see is the continuation of this desire to draw certain geometric patterns, but not purely as a mathematical exercise. These forms are tightly connected with cultural heritage, spiritual value, and personal commitment. What’s more, in many

examples they are purposely temporary, designed to be drawn, seen, and obliterated

within a short period.

In Guatemala, some villages have the custom of decorating the street before an important Catholic feast day. People use colored sand, leaves, nuts, and flower petals to create beautiful patterns that cover a wide pathway down the middle of the street. When the priest leaves the church after mass on the feast day, he leads the procession of believers down this decorated path that in some cases goes all the way around the block and back to the church. Why make these beautiful designs? They’re a way to give praise and glory to God. They’re also a source of local pride.

In Guatemala, some villages have the custom of decorating the street before an important Catholic feast day. People use colored sand, leaves, nuts, and flower petals to create beautiful patterns that cover a wide pathway down the middle of the street. When the priest leaves the church after mass on the feast day, he leads the procession of believers down this decorated path that in some cases goes all the way around the block and back to the church. Why make these beautiful designs? They’re a way to give praise and glory to God. They’re also a source of local pride.

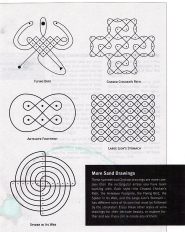

The Sona drawings in West Africa are famous as feats of both mathematical design and story-telling, two items seldom combined in western culture. The story-teller marks out a grid of dots in the sand then begins the story and the diagram at the same moment. If the diagram has only one line, it must be continuously drawn so that the diagram and the story finish at exactly the same time. Try this one, a very simple example, on a piece of graph paper. If it works, try it on plain paper. Then try to tell a story while you draw it, without stopping, of course.

You can get a larger version of the drawing by clicking on the image.

Some of the sona diagrams are very complicated, like these from “SONA: Sand drawings from Africa”; the person who can complete one of these perfectly while telling a story deserves to be the center of attention!

Some of the sona diagrams are very complicated, like these from “SONA: Sand drawings from Africa”; the person who can complete one of these perfectly while telling a story deserves to be the center of attention!

These are finished drawings, but you can find grids and explanations including steps involved in drawing many of these if you put “sona” or “West African sand drawings” in your search engine.

The same grid idea is at work in the Rangoli design from India (chalk drawing in photo). However, instead of drawing lines between the dots and following an algorithm, the artist has used the dots as guides to create a hexagon. Six 6-sided flowers form the ends of the bisected X while a seventh lies at the center of the diagram. Filling out the space are three 3-sided flowers, three 1-leaf forms, and three concentric circles. It’s a geometric delight, but its purpose is to be walked on. The designs are created, usually by women, for entryways.

The same grid idea is at work in the Rangoli design from India (chalk drawing in photo). However, instead of drawing lines between the dots and following an algorithm, the artist has used the dots as guides to create a hexagon. Six 6-sided flowers form the ends of the bisected X while a seventh lies at the center of the diagram. Filling out the space are three 3-sided flowers, three 1-leaf forms, and three concentric circles. It’s a geometric delight, but its purpose is to be walked on. The designs are created, usually by women, for entryways.

Very large versions of rangoli designs have been created to cover entire streets. Curiously, the logo for one rangoli website is a sona drawing.

The most famous sand drawings in North America are those done by the Navajo hataali (native healer) as part of a chant, a ceremony that usually takes several days. The hataali must be skilled in the complicated art of the sand paintings required for each ceremony as well as the songs that go with them. The person who is being healed will eventually sit on the sand painting, and it will be destroyed at the end of the ceremony.

The most famous sand drawings in North America are those done by the Navajo hataali (native healer) as part of a chant, a ceremony that usually takes several days. The hataali must be skilled in the complicated art of the sand paintings required for each ceremony as well as the songs that go with them. The person who is being healed will eventually sit on the sand painting, and it will be destroyed at the end of the ceremony.

In Tibet, perhaps the most complicated sand paintings of all are created by the monks as part of the initiation ceremony of new monks. The mandalas can take weeks to create and are thought to be infused with spiritual power. After three days, the sand is swept up into a pile and cast into a river so the spiritual energy collected in it may be dispersed into the world. (For information about the meaning of the symbols in the mandalas the Buddhist monks make, read the Dalai Lama’s explanation for non-Buddhists.)

In Tibet, perhaps the most complicated sand paintings of all are created by the monks as part of the initiation ceremony of new monks. The mandalas can take weeks to create and are thought to be infused with spiritual power. After three days, the sand is swept up into a pile and cast into a river so the spiritual energy collected in it may be dispersed into the world. (For information about the meaning of the symbols in the mandalas the Buddhist monks make, read the Dalai Lama’s explanation for non-Buddhists.)

It’s curious, in all of these examples, that the simple geometric forms of circle, concentric circles, circle bisected by perpendicular lines, and circle-square

combinations are so common. This is part of what people call sacred geometry, but it’s important to realize that the geometry is not an end in itself. It is part of an expression of spiritual connection and awe.