Kathleen Flanagan Rollins's Blog

September 23, 2025

A Fish Knife

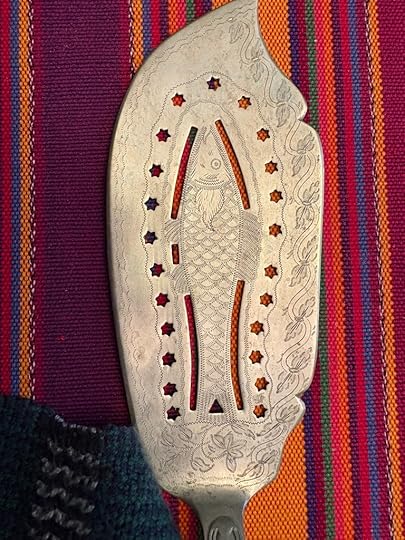

I have a fish knife. Not the kind fishermen use to clean their catch or remove the scales. It’s a serving knife made of sterling silver, about 11” long, with an engraved fish on the blade, surrounded by punched stars and etched greenery. The handle has “EHT” engraved on it. I have no idea whose initials those might be. Worse, I’ve never used it to serve fish, though occasionally it’s been helpful in getting a piece of pie out of the tin.

It’s spent the last several decades rattling around in a drawer with my other mismatched flatware, mostly inherited from dead relatives.

But this oddly ornate serving utensil is part of a national story that began in the Gilded Age, a story that includes several men who had a lot of money and at least one woman who didn’t.

The Influence of the Gilded Age

The Gilded Age, a term coined by Mark Twain, usually refers to the period between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of World War I. It describes a period of rapid expansion in the US, accompanied by widespread corruption and material excess. John Jacob Astor is a good poster boy for the era, but John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, or J. P. Morgan would also serve.

John Jacob Astor was born in 1763, in Waldorf, Germany, the son of a butcher. He immigrated to the US after the Revolutionary War and, with some help from his older brother, got involved in the fur trade in the northern territories. Since fur was vitally important in cold climates and Europeans had already killed off their fur-bearing animals, Astor saw an opportunity in buying otter and beaver pelts from traders, cleaning them up, and selling them to European markets. It was bloody, smelly work, but it made him a 300% profit over costs – or better. Then he decided to eliminate the middleman and headed west to negotiate directly with the traders and trappers. He often paid less than he promised for the pelts or substituted liquor for trade goods. Sometimes he paid so little to the traders that they wound up killing their trappers, usually Indians, rather than pay them for the pelts they brought in.

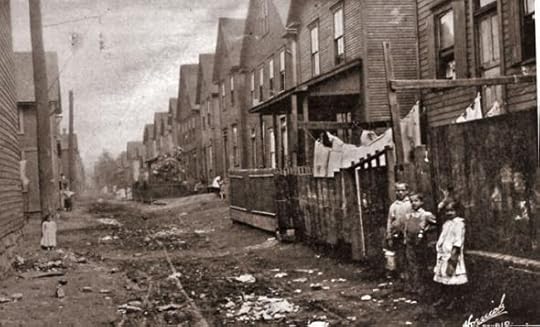

When demand for furs began to slow, Astor, with the help of his wife, Sarah Todd Astor, turned to buying up real estate, especially in New York City. The flood of new immigrants meant housing was at a premium, and Astor and his son eventually controlled most of it. He made his biggest returns on overcrowded tenements that were divided and subdivided until a family might be living in an area about the size of an elevator. Even then, the family might rent out bed space to a lodger.

At the same time, Astor joined the opium smuggling trade, shipping opium from what is now Turkey to China and later to England.

He made another fortune by lending money at exorbitant rates and by establishing company stores where employees had to pay high prices or buy on credit because there was no other option.

But Astor wasn’t alone at the top. Powerful monopolies controlled shipping, mining, railroads, meat packing, textiles, oil, coal, steel, tobacco, even fruit. The robber barons, as they became known, ignored criticism and brutally put down any worker efforts to unionize or demand better working conditions. Put this together with new waves of immigrants desperate for work and no income tax until 1913 (the 16th amendment), and you have the formula for the top 1% controlling most of the country’s wealth in the Gilded Age.

Once they had it, they flaunted it. This photo shows a sitting room in John Jacob Astor’s house in New York City.

In addition, they built summer homes north of the city or farther up the coast in Newport, Rhode Island.

Eventually, Astor was considered the richest man in America. But he needed more than money. He needed respectability. A history of success, a lineage, a heritage. He wanted a connection to older European families. Specifically, royalty. His house had to have the same décor as the royal homes in Europe. No longer the son of a butcher or a fur trader with blood on his hands, he saw himself as a king, blessed by God with rare talents that separated him from ordinary men.

The other robber barons agreed. The elaborate dinners given by Queen Victoria (1837 – 1901) helped cement her reputation and power, so the Gilded Age barons followed her example, down to the table settings and silverware. The centuries-old estates of European aristocrats provided the design templates for homes of the Gilded Age leaders. In fact, many of the greatest homes of the era sported paintings, sculptures, carpets, tapestries, and furniture purchased directly from European castles, in some way carrying with them their old-world blood claims to power.

If you want a first-hand look at this kind of life, check out the “cottages” on Bellevue Avenue in Newport. The largest, “The Breakers,”(shown in the photos) is worth the admission price just so you can gawk at the extravagance of the rooms, especially the main hall.

Other super-rich folks built their summer homes along the same street. That way they could compete and socialize with the right sort of people. Interesting side note: Beachwood, the Astor mansion in Newport, was purchased by Larry Ellison, the billionaire founder of Oracle software, in 2010, so it is no longer open to the public. But it still belongs to the 1%.

The Gilded Age was clearly an era of inequality built on greed. And yet – and here’s the odd part – working people became fascinated with the super-rich.

When the glitterati gave a party, ordinary people lined up on the streets to watch the aristocrats arrive. Local papers provided lists of all the guests and described the decorations and clothing in detail. Even the place settings. It sold a lot of papers.

We still find lifestyles of the rich and famous fascinating. Julian Fellows, the creator of Downton Abbey, has a new hit, The Gilded Age, which features several of the enormous mansions in Newport. The Breakers, along with Marble House, Chateau sur Mer, and The Elms serve as backdrops to this well-dressed production. Their opulence helps describe and define the people who play out their personal dramas there.

The Rise of the Fine Hotel

Exclusivity was always part of the Gilded Age appeal. But later, this sense of grandeur became somewhat more widely available in the most fashionable hotels, like the Waldorf, opened in 1893, and the Astoria, opened in 1897, by competing members of the Astor family. There, rich people could enjoy the same sort of luxury the very rich enjoyed, including fine dining. The photo shows a main ground floor room in the Waldorf, clearly modeled after the decor of the Gilded Age estates.

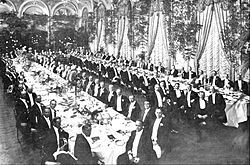

You could also go to an important dinner at the Waldorf and, for that moment at least, become one of the elite. The photo (left) shows a banquet held at the combined Waldorf-Astoria hotel in 1903. Clearly, the dress code was very strict.

If you look at the scene from Titanic in which Jack Dawson, played by Leonardo diCaprio, is invited to join the group for dinner in the first class dining room, you’ll notice the amazing array of silverware in each place setting. “Is all this for me?” Jack asks Molly Brown, who whispers, “Just start at the outside and work your way in.” In truth, knowing which utensil to use was a kind of test. Only those raised with money would know. It was as telling as the clothes you wore. https://www.google.com/search?q=You+Tube+Titanic+dinner+scene+with+Jack+and+Rose&oq=You+Tube+Titanic+dinner+scene+with+Jack+and+Rose&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUY

You can still buy full sets of sterling silver dinerware, if you’d like. They cost about $4000, though a set of English King Gold by Tiffany and Co Sterling Silver Flatware (gold over silver) service for 12 would cost you about $60.000! Sets like this are advertised as suitable for the elite, those who want to set a dining table of “unmatched luxury and heritage. It’s interesting that you get heritage along with luxury. A prestigious family history is apparently included in the purchase.

The Legacy of the Gilded AgeThe Panic of 1893 led to bank and business failures. In many ways, it was the beginning of the end for the Gilded Age, but the ostentatious display of wealth continued well into the Progressive Era. And the not-so-fancy people took notes on it. Even if they did not have millions, they could set a beautiful table, with fine china and silverware, kind of like the really rich folks. So they did. Eventually, fancy plates, silverware, and glasses became an important part of many households, handed down from one generation to the next and brought out for special occasions.

Now, though, people don’t see these things as all that impressive. Few people hold formal dinner parties. Even fewer care how you’re supposed to hold a pickle fork or an oyster spoon. Grandma’s collection of silver and china often sits unused in the basement.

That’s probably why the fish knife wound up in my drawer.

Women’s Wealth

But there’s another way of seeing that silverware.

The Gilded Age was an exclusive rich white man’s club. Women were useful in ensuring the legacy would continue through children and for displaying the husband’s wealth. But they had very little real power.

They couldn’t vote. (Women didn’t get the vote in the US until 1920, and women of color weren’t included until 1965.) They had no financial independence. (Up until 1974, a woman could not open a bank account in the US in her own name without her husband co-signing, or apply for a credit card, or get a home loan without her husband’s permission. An unmarried woman would be refused immediately.)

During the Gilded Age, when a woman married, her wealth became her husband’s property, even if she brought the money into the marriage.

However, there were exceptions. She could keep her jewels and precious metals, especially silver and gold.

Therefore, her collection of silver flatware, silver coffee service, and silver serving dishes became more than a pretty addition to the table or a way to impress guests. It was an emergency fund, her protection against the threat of destitution. As were her jewels. Many women, faced with bills to pay, secretly sold off some of their jewels and substituted fakes, hoping no one would notice.

So the silver fish knife represented two things to whoever “EHT” was: status and wealth. It said she was someone of a certain class because she had an array of silver dining implements and knew how to use them. Perhaps more importantly, It also represented her personal wealth, which was not under her husband’s control.

And it was something she could pawn when she needed cash. For reference, a sterling silver asparagus server, offered in a 2021 Jewelry, Silver, and Rare Coins Auction, sold for $310. It makes me look at the fish knife with new respect.

Sources and interesting reading:

Donnely, Leeann, “Dinner Is Served: Setting the Banquet Hall Table,” including information on A Vanderbilt House Party – The Gilded Age, https://www.biltmore.com

“English King Gold by Tiffany and Co Sterling Silver Flatware Set 12 Service 256 pieces,” originally sold for $250,000, available on Ebay, https://www.ebay.com/itm/156915667985trjoarns=amchiksrc%3DITM…

“John Jacob Astor,” Britannica Money, https://www.britannica.com/money/John-Jacob-Astor-American-businessman-1763-1848

“John Jacob Astor,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Jacob_Astor

Lewis, Jone Johnson, “ A Short History of Women’s Property Rights in the United States,” Thought Co, https://www.thoughtco.com/property-rights-of-women-3529578

Little, Leland, “Queen Victoria at the Table: The Original Influencer,” https://www.lelandlittle.com/story/queen-victoria-at-the-table-the-original-infuencer/106751/

“ A Piece for Every Food,” Antiques Q&A, https://antiquesqa.blogspot.com/22019/04/a-piece-for-every-food.html/

“Waldorf-Astoria (1893 – 1929)” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waldorf-Astoria_%281893-1929%29

Photos taken from sources listed

February 5, 2025

Carousel Horses

Last November my daughter and I took a ride on an antique double-decker carousel in San Francisco. It had decorated wooden horses, as we expected, plus some fanciful additions like a dolphin, a frog, a tiger, and the incredibly impractical hippocamp with the front of a horse and the back end of a fish.

Originally built in 1921 by Gustav Dentzel, this menagerie carousel got an extensive mechanical overhaul in 1994. In 2000, restorers dismantled, repaired, and repainted each of the animals at a cost of over a million dollars. Today it’s one of the city’s favorite attractions. What is it about this refurbished masterpiece that makes it so popular with both residents and visitors?

Perhaps it’s the fantastical combination of artistic elements, or the history, or the music, or the unexpected whimsy of it all.

The horses are decorated in a hodgepodge of themes, shapes and colors. They have tassels and folds of fabric, plus ornate breastplates and somewhat random buckles. Each one is different, sporting whatever elements struck the designer as beautiful.

Some seem to borrow from the medieval world of knights and jousting, where noblemen competed in the lists, galloping toward each other, seeking to unhorse their opponent with their lance. Since the riders wore protective armor, they were identified by the horses’ colorful trappings and heraldic symbols.

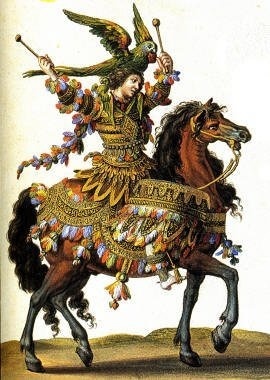

Or perhaps they were inspired by the most elaborate carousel in history – the grand equestrian pageant put on by King Louis XIV of France in 1662. The event took place between what is now the Tuileries gardens and the Louvre, in what became known as La Place de la Carousel in Paris.

The exhibition featured hundreds of costumed riders sporting incredibly elaborate gear. The king himself (above, left) joined in, dressed as a Roman emperor with a penchant for high fashion. He wore a coat embroidered with silver and gold thread and a silver helmet topped with ostrich plumes. His horse had a caparison covered in diamonds and red and gold tassels. The Duc d’Enghien’s horse (above, right) wore a heavily embroidered outfit featuring layers of tassels and gold beading. He wore more of the same, as well as puffy garlands and a headpiece topped by a parrot. Later that day he wound up winning the Brass Ring contest, probably in simpler gear.

That kind of decorative extreme became a favorite of some later carousel designers. These horses sport not just the gear knights’ horses might have worn in a joust, but also flowers, gold flourishes, embedded glass jewels and mirrors, flags, even portraits of famous people. More is definitely better, at least in carousel horses. The Coney Island style, made famous by designer I. D. Looff, became known for its over the top creations, like the horse (pictured, above), built in 1909 by Marcus Illions. It’s still part of the B & B Carousel at Coney Island, New York.

The Machine

But a classic carousel was more than art. It was also science.

The earliest forms of the carousel had simple wooden horses on a hand-cranked platform. They helped riders learn to wield their weapons without injuring their horses.

In 1850, a new version appeared at a Paris exhibition. The horses were suspended from the center pole, not the base, so they flew outward as the pole rotated, becoming the “flying horses carousel.”

In 1863, Thomas Bradshaw invented a steam engine to move the platform. Three years later, Frederick Savage developed not only lavishly decorated carousels but also the mechanism that allowed the horses, with attached poles, to go up and down as well as round and round. He called them “Platform Gallopers.”

Once the concept came to America, the carousel’s golden age began, with bigger and more elaborate animals that included exotic and mythical beasts as well as horses.

The Golden Age

Between 1870 and 1930, the perfect combination of skilled immigrant woodcarvers, steam engines (and later electric motors), public transportation, and leisure time for workers led to the development of over 3,000 carousels in the USA.

Music

These beautiful hand-carved animals needed only a soundtrack to complete the fantasy – the chirpy sounds of a Wurlitzer organ, a mechanical wonder that operated like a player piano with special effects including drums and cymbals. Some interesting videos and audio recordings are listed in the Sources.

The Decline – and Rebirth

The Great Depression changed everything, including carousel horses. The last of the classic wooden carousels was carved in 1930. Any new carousel figures were made out of metal or fiberglass. Over time, the old wooden carousels fell into disrepair. Growing demand among antique collectors meant individual wooden horses could be sold off for a handsome profit. Since 1990, several have sold for over $100,000.

So the classic wooden carousel numbers dropped from over 3000 to about 170 today. But as they declined, the few remaining examples increased in value – to the people, the businesses, and the communities that counted them as part of their identity. The Central Park Carousel in New York, The Smithsonian Carousel in Washington, DC, the Flying Horses Carousel on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, the Herschell Spillman Carousel in Ocean City, Maryland, the San Francisco Carousel at Pier 39, and others have become symbols of their cities, local landmarks and tourist favorites.

They’re each a piece of history, certainly. But they’re also a nod to a moment when art and science and whimsy came together to create something magical.

Sources and interesting reading:

“The Carousel of 1662,” This is Versailles blogspot, 28 March 2015, https://thisisversillesmadame.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-carousel-of-1662.html, also source of illustrations of the costumed riders

Coney Island style horse by Marcus Illions, built in 1909, currently housed on Coney Island, Wikimedia Commons, https://common.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coney_Illions_004.jpg

Demars, Louise Larentano,“The Golden Age of Carousels,” Carousel of Smiles, 1 December 2016, https://thecarouselofsmiles.org/the-golden-age-of-carousels/

Eschner, Kat, “The Dizzy History of Carouself Begins with Knights, Smithsonian magazine, 25 July 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/dizzy-history-carousels-begins-knights

Fraley, Tobin. The Great American Carousel: A Century of Master Craftsmanship. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1994

Hillman, Jim. Amusement Parks. Long Island City, New York: Shire Publications, 2013.

“Historic Sites – Dentzel Carousel – San Francisco Zoo and Gardens” https://www.sfzoo.org/historic-sites-dentzel-carousel/

“Jousting,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jousting

Shulman, Jim. “Learning to appreciate the history and art of the carousel, Baby Boomer Memories, 20 December 2024, https://www.berkshireeagle.com/history/different-styles-golden-age-of-carousels/article_

Sinick, Gary and Tobin Fraley. The Carousel Animal. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1987.

Carousel music recordings

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tMj6duvFJ4o Wurlitzer 165

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtsZKOscXDg Wurlitzer 105 organ

February 28, 2024

Decorative Skeletons

Until the last few years, the only time I saw plastic skeletons in people’s yards was around Halloween. They were meant to be scary. Some were positioned so they seemed to be crawling out of the earth, usually near fake tombstones. The dead coming back to life and threatening the living. They went with giant spider webs and spooky music.

They reminded me of the figures in the “Night on Bald Mountain” section of Disney’s Fantasia (1940). Skeletal humans on skeletal horses, all under the command of the bat-winged, golden-eyed demon at the top of the mountain. Mussorgsky’s piece was inspired by Russian folk tales about periodic gatherings of witches and dark spirits, including the restless dead, the ones who did not “rest in peace.”

The turning of the Celtic year

Ancient Celts had similar beliefs about the celestial turning points in the year. They felt that Samhain (October 31 – November 1) was the meeting of the light half of the year (summer) and the dark half of the year (winter). At that point, the division between this world and the world of spirits was at its thinnest, so many could cross over. While some spirits were welcomed, like honored ancestors, others were considered very dangerous. Ghosts, fairies, and other creatures on that night were under the control of the Lord of the Dead.

To the Celts, fairies weren’t cute, winged beings like Tinkerbell. They could be any size or shape, and they were angry that they’d been forced off their lands when the people arrived. So they got their revenge by causing trouble. My Irish grandmother blamed almost every misfortune on the Little People – The Others. If she couldn’t find her keys, they’d moved them. If someone got in an accident, it was probably the Others distracting the drivers. They were particularly dangerous to children and livestock.

On the night before Samhain, when the two worlds were tangled together and dark spirits drew the restless dead into their ranks, the living donned masks to scare off these evil forces and lit bonfires (bone fires from slaughtered animals) to beat back the darkness.

When the Irish came to America, particularly during the Famine of the 1840s, they brought their beliefs with them. By that time, the old Celtic traditions had been subsumed into those of the Catholic Church, so that Samhain, October 31, was All Hallows Eve, the night before All Hallows (All Saints) Day, November 1.

The Day of the Dead

In Mexico, El Dia de los Muertos (The Day of the Dead) is celebrated on November 1 and 2. It’s the remnant of an ancient Aztec festival that lasted for a whole month honoring the dead. But not as creepy, scary monsters. Photos of ancestors who are remembered fondly are placed on ofrendas, or altars, along with flowers (usually marigolds), bread, sugar skulls, and the dead person’s favorite food and drink. It’s a party to which the dead are invited. The living join in by painting their bodies like skeletons, decorating the graves of loved ones, and dining with the dead.

The movie Coco, from Disney/Pixar, is a wonderful introduction to the version of the Day of the Dead popular around the city of Oaxaca, Mexico. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rvr68u6k5sI

The Giants

Traditional Halloween skeletons and the Day of the Dead skeletons have at least vestiges of spiritual meaning, but the newest versions – giant plastic skeletons – seem to be simply yard toys.

The most popular ones are 12’ tall, though you can also find them at 6’ or 8’. The 12’ versions sell for about $300 at Home Depot. They proved to be so popular, they sold out last year.

And they’re not limited to Halloween. I’ve seen them stringing up Christmas lights and hanging Easter eggs. Sometimes they’re playing golf or relaxing in the pool. The group in the top left photo seems to be getting ready for Saint Patrick’s Day (though the background seems to indicate the photo was taken in the fall).

These skeletons are quirky, not terrifying, and because they have movable joints, they’re endlessly adaptable to whatever the property owner wishes them to represent. When one homeowner was notified that the giant skeleton in his yard violated the HOA policies which required holiday decorations to be taken down after a month, he took to redecorating it for different holidays.

But there’s something a little weird about a giant skeleton with a Santa hat. Is that dead Santa? Or is the skeleton acting as a kind of fleshless Everyman? Perhaps a third party commenting on our strange holidays? What about the skeletal Easter Bunny? If Easter is a season of rebirth, the skeleton seems to send something of a mixed message.

I agree – The creations people make with the giant skeletons are often clever and well-executed. And some installations are used to raise money for charaties like St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital. Still, even a plastic skeleton is a representation of a dead human body, and there’s some inherent danger in chuckling at the dead. Perhaps that’s part of the appeal for some folks. It’s all a little edgy. But the giants stop short of being fun for me. I guess I can still hear my grandmother’s whispers about the dangers of mocking the dead.

Sources and interesting reading:

“Celtic Otherworld,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtic_Otherworld

Pinterest has a whole page of ideas for decorating with the giant skeletons, with lots of photos: https://www.pinterest.com/search/pins/?rs=ac&len=2&q=skeleton%20decorations%20outdoor%20funny&eq=skeleton%20decoration&etslf=9113

“The giant Home Depot skkeleton is helping raise money for St. Jude Children’s,” Boston.com, 29 October 2021, https://www.boston.com/new/local-news/2021/10/29/home-depot-skeleton-st-jude-childrens-fundraiser/

Thomas, Heather, “The Origins of Halloween Traditions,” Headlines and Heroes: Newspapers, Comics and More Fine Print,” 26 October 2021, Library of Congress Blogs, ISSN 2692-2177

September 28, 2023

Wishing Trees

In the Lake District of northwestern England, a river called the Aira Beck drops 72’ in a dramatic waterfall known as the Aira Force (pictured below). It’s one of the most famous spots in the District, providing inspiration for many artists and poets, including William Wordsworth. Near the cascade is a special tree where visitors have hammered coins into a fallen trunk. Not just a few coins – many thousands of them, so many the trunk seems to be coated in metal pieces.

It’s one of dozens of “coin trees” in Scotland, Ireland, England, and Wales. Most of them are near a water source.

In 1877, Queen Victoria made a note in her journal about pounding a coin into a wishing tree on Isle Maree in Scotland. That tree, and others near it, are now covered with hammered-in coins. They’re near the healing well of Saint Maelrubha (pictured), where offerings were often made, including sacrificing bulls, right up to the 18th century. Recent research has shown human presence at the site may be over 10,000 years old.

What’s their purpose?

When asked why they pound coins into a wishing tree, people usually say it’s an offering, a payment in return for a favor, like a votive candle in church. In one sense, it’s like the coins people throw into a fountain. But in another way, it’s a communal act rather than an individual one. It’s the creation or reinforcement of a very important place, one coin at a time. There are other trees near waterfalls or springs, but each wishing tree has become, by its long history, the best place in the area to hammer in an offering.

And it has a ritual quality. Each coin is placed in a row with others, hammered in the same way, often with the hammer stone left at the site. Each piece adds to the power of the place and increases the appeal to those passing by.

Folklore and Fairies

One theory is that the practice of driving in metal bits began with an old hawthorn tree in Scotland known as the “Kissing Tree.” Local belief was if a young man could drive a nail into the tree with one hit, he could demand a kiss from his sweetheart since he was clearly a good choice as a suitor.

The coin tree near Ardmaddy House in Argyll, Scotland, is also a hawthorn, a species long associated with magic. Tradition says any wish you make on it will be granted.

Older explanations are more protective: the offerings were designed to appease the aos si, the fairies, who could easily cause mischief or disaster, particularly with farm animals.

Clootie Trees

In a study of holy wells in Ireland, Clare Monardo found that almost every town has one, though many are not labeled as such for visitors. She found them to be an amalgam of Pre-Christian and Christian practices, often decorated with offerings ranging from crosses, rosaries, religious statues, prayer cards, flowers, and photos, to strips of fabric, known as clooties, tied to a nearby tree. According to tradition of the area, the person making the wish ties a ribbon or strip of cloth to the tree after dipping it in the holy well, hoping to transfer their troubles to the tree and well.

In some places, both clooties and coins decorate the special tree.

Other versions

As the point of contact between heaven and earth, trees have always been impressive to people. The tree by a special body of water even more so. In these photos, you can see trees from many areas festooned with spiritual and commercial tokens, amplifying their impact on the viewer and therefore their power.

Photos include a spirit tree with statues of Buddha, a well with photos and memorabilia, a mysterious tree full of keys, a clootie tree by one of the many Saint Brigid’s wells, a Siberian shaman with prayer cloths, and a New Year’s Day wishing tree in Hong Kong.

In an interesting example of current events recycling the ancient past, a local businessman in Naples, Italy, donated several Christmas trees to the Galleria Umberto, to be used as “wishing trees.” People could write their wishes on slips of paper and attach them to the tree, in much the same way as people have, for centuries, left messages with statues of saints. The idea proved to be very popular, even after one of the trees was stolen by some local teenagers and had to be replaced. The papers included wishes like “Please make my mother well again,” “Please bring peace to the warring lands,” Please make this year better than last year,” and so on. One asked for a better season for the local football (soccer) club.

There are many modern versions, but none seem to have the spiritual presence and power of the ancient sites, because the spirit (tree spirit, water spirit, goddess, god, saint) has been removed. There’s no powerful entity acknowledged as the one meant to answer the request. Perhaps for those pinning their wishes on the trees, it’s enough to add them to the communal wishing area. Or maybe communal energy itself is the goal. Or, once decorated with these wishes, the tree itself becomes something more powerful than it used to be.

That seems to be the case in Yoko Ono’s work, Wish Tree, which was installed in the Sculpture Garden of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Another version, Wish Tree for Washington D. C. was installed earlier. Both feature messages written by visitors from all over the world.

Are they the same messages people thousands of years ago might have left at a powerful spirit tree next to a spring? Maybe not. But then again, maybe they’re not that far removed.

Sources and interesting reading:

“Aira Force,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aira_Force

“Clootie well,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clootie_well

Mathews, Jeff, “The Wishing Tree,” Naples: Life, Death & Miracles blog, www.naplesldm.com/wish.php#/

Meier, Allison, “Wishing Trees: Where Money Grows in the Branches” Atlas Obscura, 30 July 2014, https://www.atlasobscura.com/areticles/wishing-trees/ A great source for photos of coin trees.

“St. Maelrubha’s Well, Isle of Skye, Scots Roots blog, 15 May 2015, https://scotsroots.wordpress.com/2015/05/15/st-maelrubhas-well-isle-of-skye/

“Wish tree,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wish_tree

All photos were taken from these sources.

July 11, 2023

Cowboys

When I was growing up, just outside New York City, I saw a lot of cowboys – on television. First were shows like “The Lone Ranger” and “The Roy Rogers Show,” where I learned that cowboys had wonderful horses, like Silver and Trigger, they dressed in big hats and fancy shirts, they had a six-shooter on their hip, and they were strong men who upheld the law, even in the lawless West, wherever that was. After lots of chases on horseback, gunfights, and fistfights, they always caught the bad guy.

Some of the TV cowboys sang. Gene Autry sang “Back in the Saddle Again,” among other hits. Roy Rogers and Dale Evans sang “Happy Trails to You” at the end of each episode of their show.

https://www.google.com/search?q=happy+trails+to+you+youtube&oq=Happy+Trails+to+you+YOuTube&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUqBggAEEUYOzIGCAAQRRg7MggIARAAGBYYHjIICAIQABgWGB4yCggDEAAYhgMYigUyCggEEAAYhgMYigXSAQ8xNzY4NjU1MTE0ajBqMTWoAgCwAgA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:bc2e0bbd,vid:eEqUyNaSdvgSo a cowboy, as far as I could tell, was a handsome White man with a good heart, a fine voice, spotless clothes, and a great horse.

I wasn’t the only one watching cowboys on TV back then. In 1959, eight of the top ten shows on TV were westerns.

Later on, the cowboy image got a little more complicated and lost the singing bit. Zorro was a masked man, like The Lone Ranger, but he fought against political corruption in the ruling class, even though he was part of it. And he used a rapier rather than a gun.

“Have Gun, Will Travel” presented Paladin, a “knight without armor in a savage land,” a hired gun with a conscience – and a good deal of education. He often quoted Shakespeare or other poets while he was confronting evildoers.

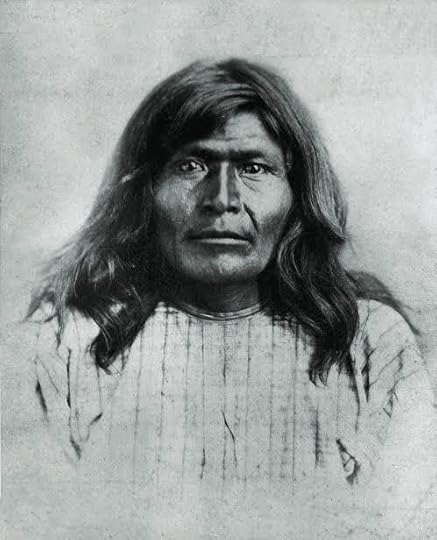

“Bonanza” was the saga of an empire built on family. Pa Cartwright and his three sons made a formidable group. The image of them riding four abreast toward the camera at the beginning of the episode reinforced the idea of their collective strength. The show was so popular that horse-crazy fans could buy Breyer models of the horses the Cartwrights rode: Sport, Chubb, Buck, and Cochise. If I had known anything about American Indian history back then, I would have found that name a strange choice, since Cochise (photo) was a famous Apache leader who fought against White expansion into their land.

But that’s only one of the problems with the TV westerns’ image of cowboys of the Old West.

“The birthplace of the cowboy”

Deep Hollow Ranch in Montauk, at the tip of Long Island, New York, claims to be the oldest ranch in the Americas, “the first home of home on the range” and “the birthplace of the American cowboy.” That claim comes from the fact that European settlers as early as 1658 used the lush grasses and natural boundary of the sea to keep cattle there.

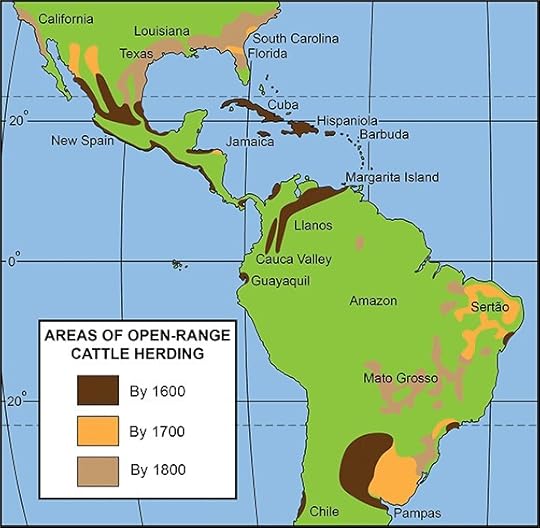

But others beg to differ about the earliest cowboys. In 1493, Christopher Columbus brought the first cattle to Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). As the native Taino population declined from disease, enslavement, and loss of resources, the cattle herds increased. Eventually, the Spanish landowners needed men on horseback to round the cattle up so they could be slaughtered for leather, tallow, and meat. These men, mostly sub-Saharan Africans, developed the technique of swinging a rope from horseback in order to catch cows.

From there, cattle ranching spread to Puerto Rico (1505), Jamaica (1509), and Cuba (1511). The first official land grant for a cattle ranch in Mexico was 1519. The Spaniards were familiar with keeping cattle on large tracts of dry grassland too big to manage without the help of horses. As you can see in the graphic, cattle ranching in the pampas of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico was well-established by 1600. All long before Deep Hollow Ranch was founded.

Vaqueros

The men who worked on the cattle ranches of New Spain, especially Mexico, were called vaqueros, from vaca, Spanish for cow. Most of these people were mestizo (mixed Spanish, Indigenous, and African descent). They braided rope from strips of leather and horsehair, made their own saddles and bridles, broke and trained horses, protected the cattle from predators, and managed the long drives from grazing areas to markets.

In 1845, The United States annexed Texas. Then President James K. Polk sent an emissary to Mexico City offering to buy California and New Mexico for $30 million, but the Mexican President refused to see him. In 1846, when skirmishes erupted along the Rio Grande, Polk used them as an excuse to declare war against Mexico. According to the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ratified in 1848, the US gained Texas, California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

As the Mexican landlords left, they abandoned most of their cattle, but many of the vaqueros stayed with them, becoming the cowboys of the new ranchlands. It’s estimated that a third of the cowhands in the American West were vaqueros.

African Americans

White Americans seeking cheap land moved into Texas even before the Mexican War, and they brought enslaved people with them. By 1860, slaves accounted for about 30% of the population. Texas joined the Civil War as a slave state in 1861, and many of the ranchers left their land to fight for the Confederacy. In their absence, the enslaved workers honed the skills necessary to care for horses and cattle. By the time the landowners returned at the end of the war, they found they had to hire now-free African Americans as paid cowhands. Demand was even greater when ranchers began selling their livestock in northern states, where prices were much higher. That meant long cattle drives to get the herds to newly created butchering centers and railroad hubs. The rough life of the cattle driver created a far more accepting environment for the former slaves than they knew before. Nat Love, an African American cowboy, said of the cowboys he worked with on the long drives, “A braver, truer set of men never lived than these wild sons of the plains whose home was in the saddle and their couch, mother earth, with the sky for a covering.” While that’s a fine sentiment, it’s worth remembering that the cowboy’s life was physically demanding, often dangerous, and paid very little. If he was thrown from his horse or gored, there was no Urgent Care or hospital around the corner. Many ranchers paid so little that the hands were essentially given only room and board.

Bill Pickett, a cowboy born in 1879 to former slaves, became famous for inventing “bulldogging,” a technique for wrestling a steer to the ground that later became a popular rodeo event.

Another formerly enslaved Black cowboy, George McJunkin, born in Texas in 1851, made history with a discovery that rocked the archaeological world. He was a self-taught naturalist and collector of ancient stone tools, as well as manager of the Crowfoot Ranch in New Mexico. After a flash flood swept through the area, he spotted what looked like enormous bison bones sticking out of a wash. He brought some back to his cabin. For fourteen years, he tried to get people to listen to him about the importance of these bones. He knew they weren’t modern bison bones. Finally, after McJunkin’s death, a blacksmith McJunkin had told about the bones convinced a banker named Fred Howarth to check out the site. Howarth enlisted the help of experts from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. In 1927, a team excavating the site found a stone spear point embedded in one of the enormous bones. They left it there and invited other experts to see it. It rewrote the history of humans in the Americas because it meant humans had been in North America much longer than previously thought.

It’s estimated that one in every five cowboys in the heyday of the cattle drives was Black Add that to the mixed heritage of the vaqueros.

A short but intense period

Between 1850 and 1890, the US expanded westward rapidly as settlers poured west in search of free land. Rail lines spread across the country, joining east to west in 1869 with the pounding in of the famous golden spike in Promontory Point, Utah. Then cattle could be driven from the Texas range to the rail hubs for shipment to the cities of the north and east, as well as the west coast. There were fortunes to be made. One cattleman bought 600 cows for $5400 in Texas and sold them in Abilene, Kansas for $16,800. He was not alone.

Suddenly, manpower was needed everywhere – to drive the cattle, to build the railroads, to build the stock pens, to establish butchering facilities and transport routes.

Chinese

The backbreaking work of building the western section of the transcontinental railroad was made possible by about 20,000 Chinese immigrants. Seen as a good source of cheap labor (like the Irish immigrants on the eastern sections), they were assigned the dangerous work of blasting through the mountains to lay track. Many were injured or killed in the process.

In addition to construction, Chinese immigrants worked as cooks, blacksmiths, miners, and farmers. When the railroad work was done and local communities forced out Chinese people, some wound up working for the cattle ranches, as cooks and as cowboys.

Jim Sam, a famous Chinese cowboy (photo), was born in China in 1859 and brought to California the following year. Later, he worked for two ranchers, doing everything from milking cows to cooking. He became an excellent horseman and joined the cattle drives for many years. Later he ran a hotel and enjoyed pretending he didn’t know anything about playing cards so he could relieve bragging visitors of some of their cash.

American Indians

Despite the Cowboys vs. Indian battles made popular in the Wild West Shows, there were many Indian cowboys in the heyday of the cattle drives. With the bison slaughtered by buffalo hunters and their people forced onto reservations, some Plains Indians set up their own cattle operations or sought work with White ranchers. They were, like the Black and Chinese cowboys, treated as inferior, but their skills, especially with horses, were essential to a successful cattle drive.

Others

Ranch work also attracted desperados – men who, for one reason or another, had to leave home. Some were wanted men. Some had lost everything in the war. Some, because of their race or ethnicity, were widely hated. Some had a past they’d rather forget. But the cowboy’s life was so demanding, it meant having to trust others in the group. Generally only eight to ten cowboys would be expected to take a herd of 300 cattle on a drive of up to a thousand miles across open country, with only a cook and a foreman to help. That meant dealing with thieves, outlaws, angry landowners, accidents, disease, drought, floods, and danger of stampede or splits. While they might not be best friends, the cowboys absolutely depended on each other – and their horses – for their survival.

Probably the best modern representation of the mix of people who were cowboys in the Old West is the 2018 remake of The Magnificent Seven (shown).

Women

Though there were probably cowgirls back then other than Annie Oakley, they don’t show up much in the historical record. Only the homesteaders like Laura Ingalls Wilder of The Little House on the Prairie fame. And the outlaws. Like Belle Starr, who dressed in black velvet and rode sidesaddle, carried two pistols and was a crack shot. She married Sam Starr, of the Starr clan, a Cherokee Indian family known for horse stealing and other crimes.

Pearl Hart was a Canadian outlaw who teamed up with Joe Boot to commit one of the last stagecoach robberies in the American West.

Lottie Deno was a notorious gambler who married another gambler who was wanted for murder. She was apparently the inspiration for Miss Kitty on “Gunsmoke,” though it’s hard to see the connection between the two. Miss Kitty never seemed to have a dark past she was running from.

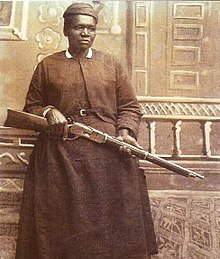

Mary Fields (photo), born into slavery around 1832 and freed after the Civil War, went to work first in Ohio, then Montana, where she became famous for drinking, smoking, and toting guns. In 1895, she became the first African American stagecoach driver, famous for her courage in standing up to bandits. Rumor has it that she fought off a pack of wolves by herself. Sounds like a great idea for a movie.

The other women, the ones who worked hard on the ranches to made them successful even in the face of constant challenges, are seldom mentioned.

The end of an era

In the 1880s, the beef boom collapsed. A drought in 1883, combined with overgrazing of some areas and more people moving into former range land, meant insufficient grass available to sustain the herds. The winter of 1886 – 87 was so cold many cattle perished.

In 1874, Joseph P. Glidden of Illinois patented barbed wire fencing for cattle. Gradually, its use changed cattle ranching. Larger operations survived, but smaller operations could no longer count on enough open range to fatten the cattle. By 1900, the open range was gone, and part of the cowboy life went with it. Cowboys typically went to work for the big operations instead of trying to run their own.

The new image

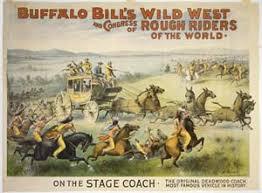

But almost as soon as the old cowboy life changed, the idea of it was picked up, embellished, and presented to the public. Wild West shows sold a dream of endless space, freedom, challenge, and adventure.

Dime novels and weekly magazines told exciting, serialized stories about savage Indians, brave mountain men, outlaws, and constant danger. “Malaeska: The Indian Wife of the White Hunter,” published in 1860, is considered the first of the genre. Well past 1900, magazines like The Wild West Weekly were still popular reading, especially in the east.

Western novels, like The Virginian by Owen Wister (1902) and Riders of the Purple Sage by Zane Grey (1912), made the image of the tough, independent cowboy hero familiar to thousands of readers who’d never been west of the Mississippi.

So it’s not surprising that as early as the 1930s, radio shows featured the glorified image of the cowboy as an amazing yet self-effacing hero, like The Lone Ranger, a Robin Hood protecting the innocent and bringing the bad guys to justice, all the while avoiding any kind of self-aggrandizement. “Who was that masked man?” someone asks at the end of each episode.

But when it came to making these stories visual, somehow all the cowboys became White men. The 1951 film Tomahawk, about Jim Beckwourth, a famous Black frontiersman, featured a White actor in the part. In the 1956 film The Searchers, which was based on events in the life of Britt Johnson, a Black man, the character was played by John Wayne, a White man. And so on, through many films and TV shows, until gradually the real stories disappeared under the many coats of whitewash.

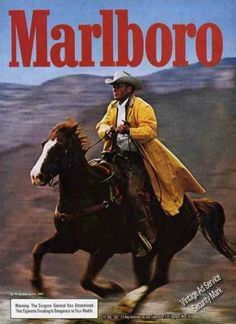

The Marlboro Man

Another image cemented the cowboy image in America’s mind – the Marlboro Man. The concept originated with a photo in Life magazine of Clarence Hailey Young, a foreman at the JA Ranch in Texas. It caught the eye of advertising executive Leo Burnett, who was looking for a way to make Marlboro cigarettes appeal to men. (They’d previously been pitched to women as “Mild as May.”) What could be more masculine than a cowboy? But perhaps not quite the weather-beaten man with the stubble beard in the photo. A more refined image. Darren Winfield, a rancher, was the first to be featured in the campaign, which was wildly successful. Over the next two years, sales of Marlboro cigarettes tripled – to $20 billion. The ads ran from 1954 to 1999, featuring various cowboys and models as the Marlboro Man. In the ads, Marlboro Country became the Old West of legend: vast, beautiful, and unspoiled. The Marlboro man was independent, strong, and handsome. And White. He wore a white or light tan cowboy hat, like the heroes of the old westerns, and he exuded quiet confidence and power.

Cowboys today

Of course, there are still working cowboys in the US, though many prefer to be called cowmen, and they still do the hard work on the ranch – breaking young horses, managing cattle, baling hay, fixing machinery, solving problems. It’s still hard work.

There are also rodeos that challenge cowboys’ traditional skills like calf-roping and bronc riding. While these were once off-limits to non-White competitors, they now include many Black, Latino, and American Indian cowboys.

And organizations like The Fletcher Street Riding Club and the Compton Cowboys are bringing the joy of riding and caring for horses as well as the idea of the Black cowboy into urban neighborhoods.

Thoughts

The erasure of some groups of people from our history and our popular culture isn’t just their loss. It’s ours too. These are people who need to be recognized and amazing stories that need to be told. Perhaps now we’ll get to hear more of them.

Sources and interesting reading:

Beardsworth, Jessie, “How the Marlboro Man Changed Advertising,” JTTB blog, https://jttbblog.com/jttb/how-the-marlboro-man-changed-advertising

“Black and Mexican Cowboys Made Up At Least 25% of the Old West,” History Daily, https://historydaily.org/black-mexican-cowboys-facts-stories-trivia/4

“The Cattle Industry in The American West” History on the Net, https://www.historyonthenet.com/american-west-the-cattle-industry

“Cowboy” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org.wiki/Cowboy

“Cowboys,” History.com, 2019, https://www.history.com/topics/19th-century/cowboys

Fox, Courtney, “10 Women Who Ruled the Wild West,” Wide Open Country, 5 May 2022, https://www.wideopencountry.com/women-of-the-wild-west-10-legendary-women/

“Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, the Singing Cowboys,” Movie Man Eric documentary on YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pb1dW7Njs8c

Gandhi, Lashmi, “How Mexican Vaqueros Inspired the American Cowboy,” History, 2 September 2021, https://www.history.com/news/mexican-vaquero-american-cowboy

“Happy Trails to You” sung by Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, with lyrics, YouTube, https://www.google.com/search?q=happy+trails+to+you+youtube&oq=Happy+Trails+to+You+YouTube&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUqBwgAEAAYgAQyBwgAEAAYgAQyBggBEEUYQDIICAIQABgWGB4yCAgDEAAYFhgeMgoIBBAAGIYDGIoFMgoIBRAAGIYDGIoF0gEPMTc1MzA2ODM3MGowajE1qAIAsAIA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:541991d8,vid:oG_fSoYFWLA

Jafri, Dr. Beenash, “Asian American Cowboys and Native Erasure,” UC Davis Diversity, Equity and Inclusion blog, reprinted from Reappropriate, 22 September 2022, https://diversity.ucdavis.edu/articles/blog/asian-american-cowboys-and-native-erasure

Lee, Donald, Forth Worth Herd Drover, “The History of the Mexican Vaquero,” Western Experience, 25 August 2021

Livingston, Dewey, “Jim Sam: The Legendary Chinese Cowboy,” Anne T. Kent California Room Newsletter, 15 September 2020, https://medium.com/anne-t-kent-california-room-community-newsletter/jim-sam-the-legendary-chinese-cowboy-66d806a29983

Nash, Stephen, “ A Hidden Figure in North American Archaeology,” Sapiens, 20 January 2022, https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/George-mcjunkin/

Nodjimbadem, Katie, “The Lesser-Known History of African-American Cowboys,” Smithsonian Magazine, 13 February 2017 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lesser-known-history-african-american-cowboys-180962144/

Sayre, Nathan F, “Review of Black Ranching Frontiers: African Cattle Herders of the Atlantic World, 1500 – 1900 by Andrew Sluyter” Pastoralism Journal, 2014, https://pastoralismjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13570-014-0008-3

Seah, May, “Why the new Magnificent Seven has an Asian Cowboy,” Today, 18 September 2016, https://www.todayonline.com/entertainment/movies/why-new-magnificent-seven-has-asian-cowboy

“Vaquero,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaquero

Western, Samuel, “The Wyoming Cattle Boom, 1868-1886” WYOhistory.org: A project of the Wyoming Historical Society, https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/wyoming-cattle-boom-1868-1886

Welch, Bob, “Native American Cowboys: Jackson Sundown, Tee Woolman and Doyle Lee,” The Team Roping Journal, 12 January 2012, https://teamropingjournal.com/ropers-stories/native-american-cowboys-jackson-sundown-tee-woolman-and-doyle-lee/

“Westerns on television,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_on_television

Williams, Leah, “How Hollywood Whitewashed the Old West,” The Atlantic, 5 October 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archieve/2016/10/how-the-west-was-lost/502850/

May 10, 2023

It’s Not An Alien Astronaut: Part II

Bloodletting, Sacrifice, and Rebirth

As covered in the previous post on the subject, the famous sarcophagus of K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, or Pakal the Great does not show an alien astronaut. It represents the King, who died in 683 CE, after ruling for 68 years.

As indicated in the illustration from Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens, the sarcophagus lies deep inside the Temple of Inscriptions, where it was discovered in 1952. Unfortunately, archaeologists at that time were not able to translate the many symbols and glyphs on the sarcophagus.

Von Danniken’s alien astronaut theory was simply an elaborate guess, supported by common science fiction themes of the time.

What’s more interesting is what it actually means. The carving on the sarcophagus is an extraordinarily beautiful presentation of Maya beliefs about the cosmos, the king, bloodletting, and rebirth.

Maya symbols and cosmology

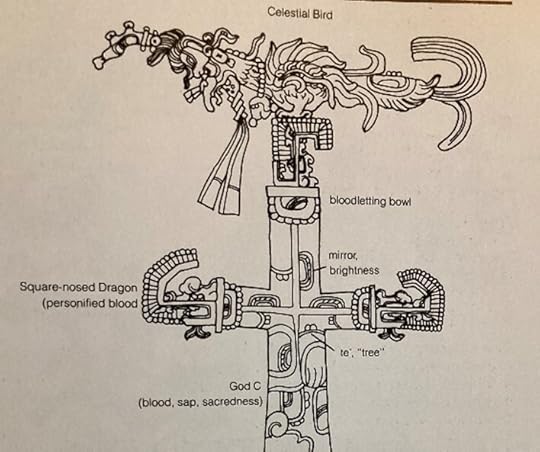

The World Tree

Maya cosmological beliefs, many of which were absorbed from earlier cultures, were fairly consistent across the Maya city-states. They saw the world as divided into three zones: The Upper World, or the land of the gods, the Middle World, where humans live, and the watery Underworld, the realm of death. The World Tree, the axis mundi, spanned all three worlds.

It took many forms, including a Ceiba tree, a stylized maize (corn) plant, and a cacao tree. That is the cruciform image you see at the center of the sarcophagus carving.

The illustrations above show two different panels from Palenque, both showing the World Tree in the center. One uses a design like the one on the sarcophagus lid, but the other makes the maize plant itself the World Tree, complete with personified ears of corn. Note that Itzamna still appears at the top, the Underworld monster appears at the bottom, but the bloodletting tools are omitted and the arms of the World Tree are branches of the maize plant rather than blood scrolls.

Bloodletting

On the sarcophagus lid, Itzamna, the creator god, shown as the Celestial Bird, perches at the top. Right below it is a blood scroll and a bloodletting bowl. The sign for mirror/shining appears on the bowl and several times on the tree itself.

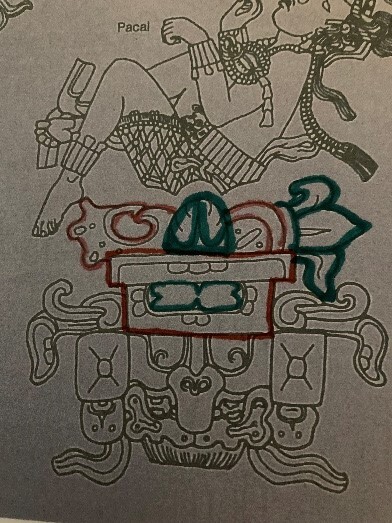

Under the figure of Pakal is another bloodletting bowl (outlined in red in my illustration) marked with the “kin” or day/sun sign (marked in green) and topped by the tools of bloodletting: an obsidian lancet, a stingray spine, and the symbol for death, balanced by new maize growth on the right side.

You can see a similar arrangement of bloodletting bowl and tools in the top of the headdress of a ruler in a stela at Copan, in northern Honduras (middle illustration above). Again, the bowl is marked with the kin sign, but in this image, the cross sky bands appear on the left, the stingray spine in the middle, and the obsidian blade on the right.

The Royal Duty

Bloodletting was considered the duty of Maya royalty, both men and women. The gods made humans from maize and blood, and they needed regular infusions of blood to keep the world going. A ruler’s blood gift allowed the entire community to thrive. It provided “ch’ulel,” the soul-stuff of the universe. The illustration on the left above shows a blood-spattered cloth in an offering bowl.

A famous carving from the Maya city of Yaxchilan (detail and full lintel above) shows the queen drawing a barbed rope through her tongue. The blood drips down the rope to the bowl. Note the shape of the bowl and similarity to the images on the sarcophagus lid.

The king was expected to undergo ritual bloodletting from his tongue, ears, or genitals.

The section of a panel from the Bonampak (Mexico) site in the middle of the two images above shows one of the gods impaling himself to provide the blood needed for creation. A sacrificed deer is shown on the right. The blood scrolls fertilize the World Tree.

Bloodletting tools were considered so important they were often interred with the dead.

Pakal and the Maize God

On the sarcophagus lid, Pakal is shown at the moment of his death falling down the World Tree toward the Underworld, the land of the dead, marked by the Earth Monster with its skeletal jaw and death signs. Yet the image is not one of an old man dying. Pakal appears as a young man, specifically the young Maize god (statue, right). His hair style, dress, even hand gestures identify him.

Pakal is becoming a sacrifice and undergoing a transformation – dying and being reborn as a god. His hands are bound, but the turtle symbol that is tied to them represents the rebirth of the Maize god from the shell of a turtle. The position of his legs mimic the “unen” or baby sign.

His death is a creative act. His blood will fertilize the sacred tree at the center of the world, and he will be reborn.

Ancestors and nobles

Pakal is not alone in his journey.

All along the border on the outside of the lid are references to celestial bodies and six portraits of leading nobles. The coffin inside the sarcophagus is carved on all four sides with portraits of Pakal’s ancestors emerging as trees sprouting from the ground, marked by the swirling earth sign below the figures. Painted stucco figures on the walls of the tomb echo these references to relatives and important figures in the life of the leader who was laid to rest in the tomb.

Apparently, the artists responsible for the paintings of the ancestors ran short of time, for some of them remained unfinished when the King died.

Thoughts

The image on Pakal’s sarcophagus lid does not show an alien astronaut. It tells a complex story of a human ruler dying and falling into the Underworld, but like the maize seed, he is being buried in the earth only to rise to a new life. He is both falling down the World Tree and rising back along it.

He is presenting his death as the ultimate blood offering and sees himself being reborn as the Maize God. Those of you familiar with Christian beliefs about the death of Jesus Christ as the offering required to save the world will find interesting echoes here.

Sources and interesting reading:

Baudez, Claude-Francois. Maya Sculpture of Copan: The Iconography, Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

Coe, Michael and Mark Van Stone. Reading the Maya Glyphs. London: Thames and Hudson, 2001.

Martin, Simon and Nikolai Grube. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000. An excellent source.

Miller, Mary Ellen. Maya Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson, 1999

Montgomery, John. Dictionary of Maya Hieroglyphs. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2002

Montgomery, John. How to Read Maya Hieroglyphs. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2002

Schele, Linda and David Freidel. A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: Quill, William Morrow, 1990.

Schele, Linda and Mary Ellen Miller. The Blood of Kings. New York: George Braziller, Inc in association with Kimbell Art Museum, 1986. An excellent source.

Stone, Andrea, and Marc Zender. Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. London: Thames and Hudson, 2011

All illustrations used in this post are taken directly from the books listed.

February 13, 2023

Valentine’s Day

For Valentine’s Day this year, Americans are expected to spend about 22 billion dollars on gifts for romantic partners, family members, friends, and pets. The most popular gifts for the day are chocolates (not for the pets), flowers (particularly red roses), jewelry, fine dining, and greeting cards.

The interesting 3-D card shown on the left includes most of the traditional symbols: the predominantly red color, the heart symbol, the word “valentine,” a suggestion of lace, and red flowers. We’re missing Cupid, but he shows up in lots of silhouettes, and he’s a major player in older valentines, like the one shown. So are white doves and swans.

While all of these elements are widely accepted today, their history isn’t exactly what we were told.

Saint Valentine

It’s called Saint Valentine’s Day, but it’s not clear why. There are dozens of saints named Valentine in the Catholic Church pantheon, but they weren’t patrons of love. One or perhaps two might have been decapitated on February 14, 269 or 270 CE during the Roman persecution of Christians. We get this information from a history of saints written over 1300 years after the fact by a Jesuit scholar named Jean Bolland in 1643.

According to Bolland, one of those beheaded was Valentinus, whose skull was whisked away after his death and broken into pieces, each of which was said to have curative powers. Churches in Madrid, Dublin, Prague, Malta, Glasgow, and Lesbos all claimed to have bits of it. One bishop said he put out a forest fire and cured demonic possession with a fragment of the skull.

However, the tales of Saint Valentine carrying notes between lovers jailed by the Emperor seem to be popular Medieval tales without much basis in history, even Bolland’s.

Lupercalia

If Valentine’s Day didn’t start with Saint Valentine, where did it come from? The most likely candidate is an ancient Roman festival called dies Februatus, which is supposed to have come from the earlier Greek festival of Pan/Lupercus, a goat/man or wolf/man hybrid which had its own priesthood, known as the Brothers of the Wolf (Luperci). Each year, in the Lupercal Cave, the priests would sacrifice one or more goats. After the feast that followed, the Luperci cut off strips of goat skin. Then, according to Plutarch, “many of the noble youths and magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery and the barren to pregnancy.”

The festival was already a regular feature of the Roman calendar by the time Julius Caesar used the occasion to refuse a golden crown in 44 BC.

Of course, many refuse to admit any connection between Lupercalia and Valentine’s Day. But there is one clear link. In the etching showing the lads enjoying smacking the ladies with shaggy strips of goatskin, there’s a familiar figure: Cupid.

Cupid

In typical Valentine’s day graphics, Cupid is shown as a winged baby boy who carries a bow and arrow. He’s often described as cherubic. He has wings, true, but he’s no angel.

In Greek mythology, Eros (known to the Romans as Cupid) was the son of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty. Her symbols were doves, roses, swans, apples, and pomegranates, as well as the color red. Perhaps the cards should read “Happy Aphrodite’s Day.”

According to some sources, Cupid’s father was Mars, the god of war, which would make Cupid the offspring of love and war. Originally he was depicted as a handsome young man who had the power to make people fall in love, even against their will. He was depicted on vases as far back as 900 BCE, a representation of passionate, irrational desire. In 500 BCE, Euripides described Cupid as able to arouse love “with murderous intent, in rhythms measureless and wild.”

He carried two kinds of arrows: gold-tipped arrows that aroused desire and lead-tipped arrows that aroused hate.

The statue of the young man Eros/Cupid in Piccadilly Square, London, is shown on the left.

The Romans, uncomfortable with the Greek version of Eros, changed him into a winged boy who did the bidding of his mother, the goddess of love. And that’s the figure that painters included in their works when all things related to ancient Greece and Rome became fashionable once again during the Renaissance. Petrazzi Adolpho painted the slightly younger version of Cupid in “Eros Triumphant” (center). In later paintings, he becomes younger still, until he’s hardly a toddler, like the baby boys in “Les Amours des Dieux” by Francois Bouché (right). In these paintings, Cupid carries his bow to shoot arrows of love. Because he’s young and small, he’s cute rather than threatening.

The Heart Symbol

Cupid fires his arrows into a heart, arousing desire. But up until the 15th century in the Middle East and Europe, the liver was considered the seat of all emotions and the origin of the body’s blood, not the heart. When you look at it, though, the design on the valentines doesn’t look much like a liver or a heart. So where did the idea come from?

Images like the heart symbol appear on ancient pottery from the Mediterranean regions, but they represent ivy, grape, or fig leaves, not a heart.

A clear heart-shaped symbol appears on a coin (shown, below) from ancient Cyrene in North Africa (300 BCE), depicting a silphium seed. Silphium was used as a seasoning, perfume, aphrodisiac, and medicine, especially as a form of birth control. It was known to ancient Egyptians and popular among many Mediterranean cultures. Romans said it was worth its weight in silver coins. Once a major trade item, unfortunately it fell victim to over-harvesting and climate change.

In 1250, a French love poem described two lovers peeling a pear with their teeth. In the illustration, the man hands his “heart” to the woman. It’s pear-shaped. Though some sources claim this is the first instance of the heart symbol, it still looks like a pear to me.

The best guess seems to be that our modern heart graphic came from playing cards.

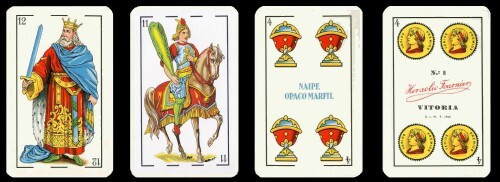

Gaming cards emerged in China in the 10th century. Through trade networks, the idea spread to India and Egypt in the 1300s. They replaced the Chinese numeric system with four suits: cups, coins, swords, and polo sticks.

From there it spread across the Mediterranean and into Europe, where the suits’ names were influenced by those in tarot cards: swords, clubs, cups, and coins (shown above left).

Each area adopted their own names. The Germans and French turned the cups/chalices suit into the heart symbol we’re familiar with today.

By the 1500s, the heart symbol was popular throughout Europe, frequently used in reference to courtly love.

Chocolate

And in that heart-shaped box we have – chocolate. Cacao was considered a food of the gods by the Mesoamericans who blended the ground seeds with hot chilies and drank the bitter, frothy mixture.

After sugar became widely available in Europe, the product of enslaved workers on sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean, Swiss confectioners mixed sugar, ground cacao seeds, and milk to create milk chocolate. At first it was reserved for the very rich, but soon its popularity spread. It was considered a taste delight and an aphrodisiac.

Cupid reappears here, linked to chocolate by the genius of Richard Cadbury, who was looking for new ways to use cocoa butter. In 1861, he came up with “eating chocolates,” which he packaged in beautiful heart-shaped boxes decorated with Cupids and rosebuds. Soon Milton Hershey and Russell Stover followed suit. Stover’s most popular was the Secret Lace Heart, assorted chocolates in a box covered in satin and black lace.

Changes

All those elements – the chocolates in the heart-shaped box, the lace and jewelry and red roses and promises of sex – are part of the Valentine’s Day experience we’ve come to expect from advertisers. But its very narrow focus makes some people hate the holiday. Some say it only makes those without romantic partners or those in bad relationships feel worse. Some say they feel forced to buy expensive gifts or put up with crowded restaurants just to prove they care. Some say no matter what they do it won’t live up to the hype.

Perhaps the holiday needs an update. From the selection of valentines I saw, the focus now seems much broader than just romance. The cards celebrated a range of loved ones – relatives, friends, teachers, kids, even pets. One I found says “Happy Hearts Day” on the front. Inside, it says, “Today is for thinking about the people who make a difference in our lives, the ones we want the best for and care about, no matter what. That’s why I’m thinking about you today.” It’s unrelated to the usual complications of Valentine’s Day. It’s just a lovely sentiment.

Another one I like featured a smiley face on the front, with the words, “You’re a nice human.” Inside it says, “Thanks for always being you! Happy Valentine’s Day.” Now there’s an uncomplicated compliment.

Happy Valentine’s Day – or Aphrodite’s Day – however you choose to mark it!

Sources and interesting reading:

“Aphrodite,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aphrodite#Genealogy

Henderson, Amy, “Chocolate and Valentine’s Day Mated for Life,” Smithsonian Magazine, 12 February 2015, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-chocolate-and-valentines-day-mated-life-180954228/

Bitel, Lisa, “The Gory Origins of Valentine’s Day,” Smithsonian Magazine, 14 February 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/gory-origins-valentines-day-180968156/utm

Valentines from American Greetings, which I bought, include the first one pictured and the last two mentioned, American Greetings, Cleveland, Ohio.

Combs, Sydney, “Valentine’s Day wasn’t always about love,” National Geographic, 5 February 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.co/culture/article/saint-st-valentines-day

Crockett, Zachary, “Why is heart emoji so anatomically incorrect?” Priceonomics.com, https://priceonomics.com/why-is-the-heart-emoji-so-anatomically-incorrect/

Dempsey, Bobbi, “Why is Cupid the Symbol of Valentine’s Day?” RD.com, 15 January 2022, https://www.rd.com/article/why-is-cupid-the-symbol-of-valentines-day/

Engel, Steve, “Sex. Lies, and Valentines,” The Crimson, 14 February 1996, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1996/2/14/sex-lies-and-valentine-phappy-or/

Greenspan, Rachel, “Cherubic Cupid Is Everywhere on Valentine’s Day. Here’s Why That Famous Embodiment of Desire Is a Child,” Time Magazine, 13 February 2019, https://time.com/5516579/history-cupid-valentines-day/

“Lupercalia,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lupercalia

McNair, Kamaron, “Americans plan to spend nearly $26 billion this Valentine’s Day – here’s what they’re buying,” CNBC.com, 29 January 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/29/americans-plan-to-spend-nearly-26-billion-this-valentines-day.html

“Playing Card Facts & Trivia,” The Playing Card Factory, https://theplayingcardfactory.com/history

“Silphium,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silphium

Thalhammer, Nick, “The Real Story of Cupid (and other Valentine’s Day Traditions) Cincinnatus Insurance LLC, https://www.cincinnatusinsurance.com/real-story-cupid-valentines-day-traditions/

“Who is Cupid & How Did He Evolve Into Our Modern Valentine’s Day Cupid,” Always the Holidays, 4 February 2022, https://alwyastheholidays.com/who-is-cupid-valentines-sday-cupid/

Yalom, Marilyn, :How did the human heart become associated with love? And how did it turn into the shape we know today?” Ideas, TED.com, https://ideas.ted.com/how-did-the-human-heart-become-associated-with -love-and-how-did-it-turn-into-the-shape-we-know-today/

February 2, 2023

Thumbs Up

Recently I received an alumnae magazine from my old high school. The cover photo featured a young woman in her graduation cap and gown. She sported a big smile and gave the viewer two thumbs up, which struck me as odd. Perhaps it’s because I associate the grin and thumbs up with older (mostly male) politicians. Some use the gesture so often it becomes a sort of trademark image. It might be accompanied by a wink, a grin, or an outstretched pointer finger in the other hand. It’s a practiced pose.

According to some sources, the thumbs-up gesture became popular during World War II among fighter pilots who used the sign to indicate from the cockpit that they were ready for take-off. It was easy to see and understand from the ground. It also carried some of the cool bravado of the fighter pilot. So it soon spread.

Maybe it’s this sense of warrior cool that the politicians are trying to convey.

Gladiators

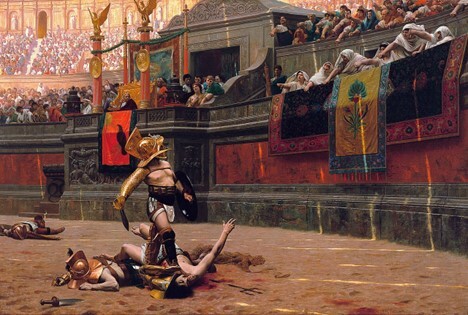

An even earlier origin story is from the Roman Empire’s gladiator battles. If you saw Russell Crowe as Maximus in Gladiator, you know the dramatic scene in which Emperor Commodus holds his thumb out sideways and then turns it down, indicating that Maximus should kill his opponent. Maximus instead spares the man’s life, infuriating the Emperor.

That gesture, the thumbs down, appears in the movie because of a famous 1872 painting by Jean-Leon Gerome entitled “Pollice Verso,” The Turned Thumb. (Painting and detail from it pictured above.) In it a rabid crowd in the Roman Coliseum calls for the death of a combatant by giving the thumbs down signal. Ridley Scott, the director of Gladiator, said, ”That image spoke to me of the Roman Empire in all its glory and wickedness. I knew right then and there I was hooked.” However, the painter might have gotten his facts confused. In some cases, the gesture used to spare a life was the thumb pressed into the inside of the fist, perhaps like the sword being returned to its sheath. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter. The gesture has gone down in popular belief as thumbs up = life while thumbs down = death.

Happy Days

Fonzie, played by Henry Winkler, helped bring back the thumbs up gesture in Happy Days, the TV sitcom set in the somewhat idyllic 1950’s of Middle America, which aired from 1974 to 1984. When Fonzie gave the thumbs up, it meant cool, young, and hip, self-assured and likeable. Not exactly fighter pilot or gladiator. Definitely more fun. Again, though, it is exclusively male. It goes with Fonzie’s Triumph motorcycle, leather jacket, and slicked-back hair.

Two Thumbs Up

Over the same time period, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, two movie critics in Chicago, put together several television series using the signs “Thumbs up” or “Thumbs down” to describe their views of current films. If one reviewer was particularly enthusiastic about a movie, he would give it “two big thumbs up.” On the other hand, they didn’t hesitate to call out what they saw as a bad film by giving it a “thumbs down” or even a skunk, for the Stinker of the Week award.

The thumbs up/down signal in these shows meant general approval or disapproval rather than anything associated specifically with males or warriors or even coolness.

The real popularization of the thumbs-up sign came with the rise of Facebook, which introduced the thumb-up sign in 2009 to mean “like” – a broad term that encompasses agreement, approval, appreciation, or simply acknowledgement. During initial discussion, the feature was referred to as “awesome” and was marked by a star or a plus sign. However, it was the thumbs up sign that was officially adopted and has since became synonymous with Facebook.

But problems arose, right from the start. Users complained that the Like/thumbs up response was too vague. Does it mean “I agree!” “OK,” “Got it,” “Whatever,” “Thanks for posting this. It made my day,” “I read your post,” or “ Amazing”? If your friend posted something about the death of their dog, would you respond with a thumbs-up?

In response to user demand, Facebook added new emoji response options in 2015: “Love,” Haha,” “Wow,” ”Sad,” and “Angry.” “Yay” was considered but never adopted. In 2020, Facebook added the “care” emoji, with the face hugging a heart. Despite many requests for a “Dislike” button, it was never added.

Other problems with the thumbs-up image necessitated a more massive change. It’s considered a vulgar gesture in many cultures. Think middle finger raised. A sexual insult. It can also mean the number one (Germany and Hungary) or the number five (Japan), a directional symbol, the hitchhiking gesture, or other possibilities.

A scuba diving instructor told me that the thumbs-up sign underwater means you’re heading up toward the surface, not that you’re okay.

Given this potential for misunderstanding, in 2021, Facebook replaced both the name and the thumbs-up icon so synonymous with Facebook with a slightly droopy infinity loop, the logo of the newly branded Meta.

In the end, it may be so deeply rooted in our culture that it will continue with or without Facebook’s help. The image on the cover of the alumnae magazine that bothered me is a product of two different cultures clashing. While I see the gesture as a kind of male bragging, the woman in the photo, having grown up with the symbol on social media, probably sees it as a sign of celebration and success.

Sources and interesting reading:

Bryner, Jeanne, “Why the thumbs-up won’t go away,” NBC News, from Live Science, 23 May 2008, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna24792764

Cunningham, Ryan, “The strange, brief history of Trump’s trademark thumbs up,” The Outline, 31 May 2018, https://theoutline.com/post/4748/trump-thumbs-up-sign

“Dispelling Some Myths: Thumbs Up,” Tastes of History, 21 June 2020, https://www.tastesofhistory.co.ik/post/dispelling-some-myths-thumbs-up

Fabry, Merrill, “Where Does the Thumbs-Up Gesture Really Come From?” History@Time.com, 25 October 2017, https://time.com/4984728/thumbs-up-thumbs-down-history/

“Like Button,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Like_button#

“The Meaning and origin of the expression: Thumbs Up,” The Phrase Finder, https://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings-thumbs-up.html

Morse, Felicity, “Facebook dislike button: a short history,” Newsbeat, BBC, 16 September 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-34269663

Smallwood, Karl, “The Truth About Gladiator Thumbs Up,” Today I Found Out, 23 October 2014, https://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2014/10/give-thumbs-gesture-get-start/

“Thumb Signal,” Wikipedia, https//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

“The Thumb Up,” Gestures: Their Origin and Meanings by Desmond Morris and others, 1979, https://bernd.wechner.info/Hitchhiking/Thumb/

“Thumbs Up emoji” Emoji Dictionary, 7 March 2018, https://www.dictionary.com/e/emoji/thumbs-up-emoji#

“Why You Should Stop Using Thumbs-Up Emoji in Chats Right Away,” News 18, 04 March 2022, https://www.news18.com/news/buzz/why-you-should-stop-using-thumbs-up-emojis-in-chats-right-away-4836146.html

Yip, Patrick, “Why Did Facebook Change Its Thumb Icon?” One Sky, https://www.oneskyapp.com/blog/facebooks-missing-thumb-may-just-design/

August 12, 2022

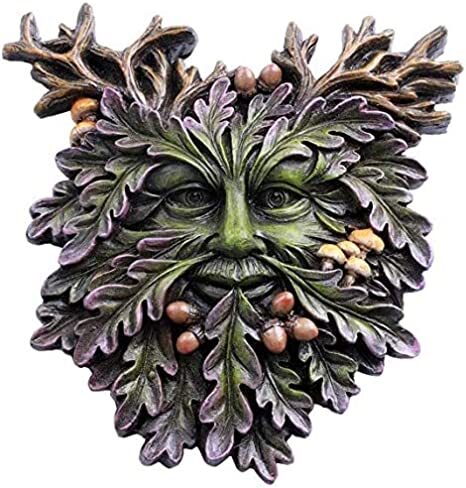

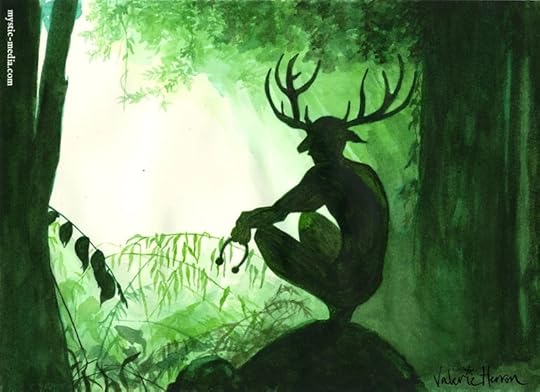

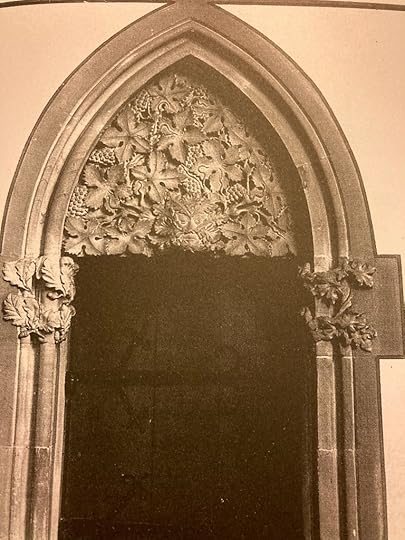

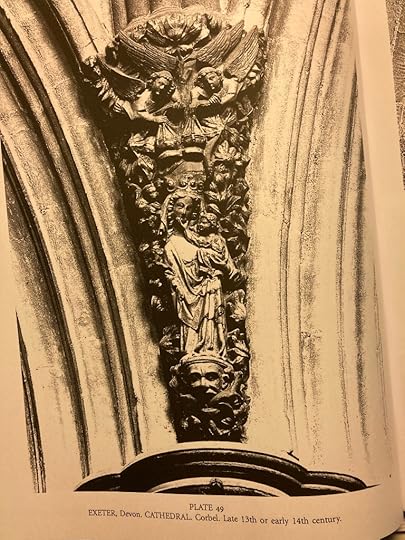

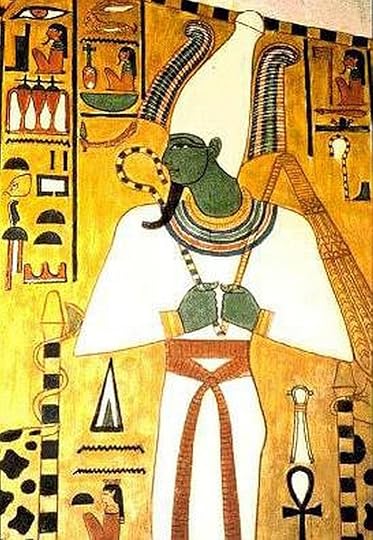

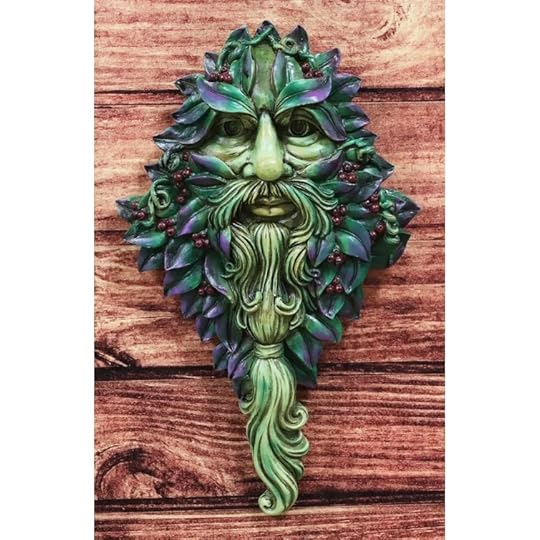

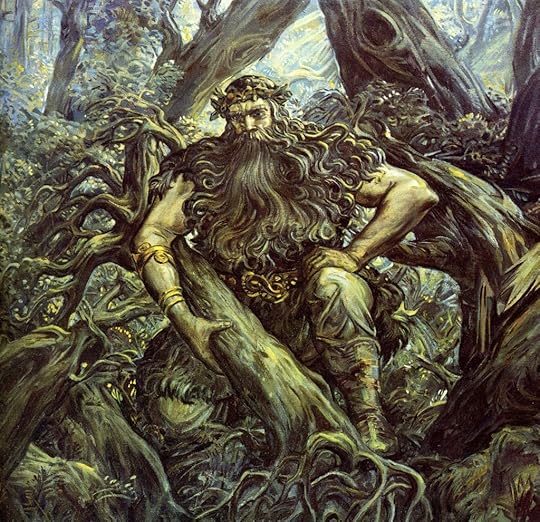

The Green Man