Donald Miller's Blog, page 113

November 16, 2011

Man In the Arena

Today's guest post is from Sarah Raymond Cunningham, the author of multiple books. Sarah quit her job so she could write what she's passionate about and keep building a community called STORY. She also contributes to projects she believes in at People of the Second Chance. You can follow her newest endeavors, like onethousandpremieres.com, at her blog, www.sarahcunningham.org.

Today's guest post is from Sarah Raymond Cunningham, the author of multiple books. Sarah quit her job so she could write what she's passionate about and keep building a community called STORY. She also contributes to projects she believes in at People of the Second Chance. You can follow her newest endeavors, like onethousandpremieres.com, at her blog, www.sarahcunningham.org.

I hope I'm not the only person whose life circles back to different versions of the same question:

Should I sink my energy into tackling new ambitious projects? Into chasing some noble goal?

Or … should my ambition be to relax off the hero button for a while; to settle into a more natural, less-stressful life rhythm? Could the simple acts of living and loving somehow be just as noble?

To top it all off, I face this question without the infamously Christian "life verse". (I have a life Bible, does that count?)

I don't even have a life mission statement tacked to my mirror or refrigerator or car dashboard.

What I do have is a little visual that's all my own. It doesn't feel commercial or gimmicky or demanded of me by some charismatic leadership figure. The visual is inspired by a quote that I ran across a long time ago and it stuck in my soul like a dart to a bullseye.

The quote is from Teddy Roosevelt.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

The visual in my mind when I read it is a mix of all the epic arena scenes—a little bit Ben Hur, a little bit Gladiator, maybe even a little bit Rudy.

All of those arenas boil down to a visual, something I could sketch for you on one of those old school transparencies that people used to lay on projectors. In the scene, there are two main spaces—the playing field where champions do battle and the platformed seats where spectators sit.

The obvious thing to say here is that I want to be the man in the arena, right?

And I do. I would rather be criticized for attempting something valiant, than to never know what it tastes like to do so. I want to spend as much time on the field as I possibly can. I want to always believe there is one more fight to be had. To thirst for my Rocky 5, 6, and 7.

BUT … the older I get, the more I believe that although I want to spend the majority of life in the arena, it's not healthy to live one's whole life there.

People who try to fight every day, day after day, often become unnaturally exhausted. Their leadership starts to come from a desperate place; they start to develop ruthless qualities that subtract from their humanity.

Some days, its right to pour it out on the playing field—to bleed and be wounded with the best of them. But on a few reserved days or stretches of life, it might be just as right to sit on the sidelines; to recoup, to learn, and to believe in someone else's battle.

That's not less courage or nobility talking, it's the wisdom life beats into me.

Because here's the thing: I want to spend the majority of life in the arena, not just now—not just for this year, not just for this decade, but for the long haul. Forty years from now, if you check in on me, I want you to see me armoring up my frail, elderly body and leading a new charge.

To love the arena life that long requires a balance, I think. It means loving the many days where I grit my teeth and fight, but to equally love the life stages when it's my turn to experience renewal and invest in or celebrate someone else advancing.

When life circles back to these points of reflection, I like to pull out my metaphorical arena transparency and lay it over my life. I like to ask myself :

1. Am I in the arena? Or am I in the stands?

2. Where am I spending the majority of my time?

3. Has it been too long since I've been in the arena? Or have I been in the arena so many consecutive days that I have nothing left to give?

I hope I am not the only person whose life keeps circling back to different versions of the same question. Examining life is part of what keeps it meaningful, don't you think?

And I'm convinced the more of us who ask these questions, the more of us who will be there—ten, twenty, thirty years from now—warriors locking eyes in our familiar duty; pledging our allegiance to God, to goodness, to purpose for life.

Man In the Arena is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 15, 2011

What the Eisenhowers Knew

The first think you will notice when you move in with a healthy family is that they cannot work independently. In the first place, there is too much labor involved in raising kids for anybody to sit on the couch for an extended period of time. They are a unit, like a body with different organs or a car with different working parts. I lived with this sort of family for a while, the MacMurrays. Both John and Terri MacMurray provided incomes. Terri had a great job at an insurance agency downtown and didn't want to leave because they needed the health benefits. They liked her so much that she worked from home most days, but she still worked. John looked after the kids when Terri was busy or running errands in town, and Terri looked after everything when John was on a photography trip. But it wasn't just the adults that had important roles. In a way, so did the kids. It was obvious, watching them and being around them, that John and Terri took great delight in their children. They were better than television to them. And the kids felt important, I think, because they would do silly things to make their parents laugh or dangerous things and have John or Terri yelling or talking them down off the balcony railing.

The first think you will notice when you move in with a healthy family is that they cannot work independently. In the first place, there is too much labor involved in raising kids for anybody to sit on the couch for an extended period of time. They are a unit, like a body with different organs or a car with different working parts. I lived with this sort of family for a while, the MacMurrays. Both John and Terri MacMurray provided incomes. Terri had a great job at an insurance agency downtown and didn't want to leave because they needed the health benefits. They liked her so much that she worked from home most days, but she still worked. John looked after the kids when Terri was busy or running errands in town, and Terri looked after everything when John was on a photography trip. But it wasn't just the adults that had important roles. In a way, so did the kids. It was obvious, watching them and being around them, that John and Terri took great delight in their children. They were better than television to them. And the kids felt important, I think, because they would do silly things to make their parents laugh or dangerous things and have John or Terri yelling or talking them down off the balcony railing.

It all reminded me of a book I read a few years ago called At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends. It was written by Dwight D. Eisenhower, the World War II general who became president. I've always been curious about successful men, leaders, and what they know that the rest of us don't. This book was entertaining because Eisenhower was a character, nearly getting himself kicked out of West Point, causing a lot of trouble. But always there was in him a sense of confidence, a sense he would become somebody important. And more than this, he believed the world needed him — that if he didn't exist, things would fall apart. He believed he was called to be a great man. I wondered, as I read, where he got this confidence.

I found the reason for Eisenhower's confidence early on in the book, in a chapter in which he discussed his childhood. Dwight Eisenhower said that from the beginning, his mother and father operated on an assumption that set the course for his life: that the world could be fixed of its problems if every child understood the necessity of their existence. Eisenhower's parents assumed, and taught their children, that if their children weren't alive, their family couldn't function.

If you think about it, it isn't just kids without fathers who don't usually feel important; it's most of us. I mean, can you imagine growing up believing that if you didn't exist, your family would fall apart? Can you imagine how different the world would be if all children were taught this idea?

This passage was an excerpt from Father Fiction: Chapters For a Fatherless Generation.

What the Eisenhowers Knew is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 14, 2011

Patience and Trust, or Why God Is Like France In That Way

Relationships aren't the best thing, if you ask me. People can be quite untrustworthy, and the more you get to know them—by that I mean the more you let somebody know who you really are—the more it feels as though something is at stake. And that makes me nervous. It takes me a million years to get to know anybody pretty well, and even then the slightest thing will set me off. I feel it in my chest, this desire to dissociate. I don't mean to be a jerk about it, but that is how I am wired. I say this because it makes complete sense to me that we would rather have a formula religion than a relational religion. If I could, I probably would have formula friends because they would be safe.

Relationships aren't the best thing, if you ask me. People can be quite untrustworthy, and the more you get to know them—by that I mean the more you let somebody know who you really are—the more it feels as though something is at stake. And that makes me nervous. It takes me a million years to get to know anybody pretty well, and even then the slightest thing will set me off. I feel it in my chest, this desire to dissociate. I don't mean to be a jerk about it, but that is how I am wired. I say this because it makes complete sense to me that we would rather have a formula religion than a relational religion. If I could, I probably would have formula friends because they would be safe.

I have this suspicion, however, that if we are going to get to know God, it is going to be a little more like getting to know a person than practicing voodoo. And I suppose that means we are going to have to get over this fear of intimacy, or whatever you want to call it, in order to have an ancient sort of faith, the same faith shared by all the dead apostles.

Jesus helps, to be sure, because He comes off as more or less trustworthy. If it weren't for Jesus, it would be difficult for me to follow God. When you read the Old Testament now, knowing exactly where the Book is going, it is all very easy and simple, but it wouldn't have been that way to the characters in actual history. If I had been around back in the Old Testament, God would have come off as more or less frightening. And I don't think I would have been able to know in my heart that it was the grandness of His nature, not the ease of His anger, that produced the fear.

My friend Penny's dad says he thinks God was angry for a while after the Fall, then got over it, sent His Son, and now is pretty well adjusted and forgiving. And of course I don't think that is exactly how it is, but I can understand why Penny's dad would read the Bible this way. But my other friend John MacMurray says that every time he gives the Bible to a person to read for the first time, even if they don't agree with it, they see God as a Person who is incredibly patient with humanity. John pointed out that it takes God hundreds of years to finally get angry enough to lay any sort of punishment on His enemies. He's like France in that way.

This passage was an excerpt from Searching for God Knows What.

Patience and Trust, or Why God Is Like France In That Way is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 13, 2011

Sunday Morning Music: Dolorean

Dolorean is a Portland band fronted by Al James, the brother of a friend of mine. You can't go wrong with any of their albums, but I recommend The Unfazed and Violence in Snowy Fields as a place to start. Here's a sampling.

Sunday Morning Music: Dolorean is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 10, 2011

Remembering Norman Mailer

I first picked up The Executioners Song about ten years ago at Powell's and this was my introduction to the writing of Norman Mailer. He was a pioneer, a creator, an innovator helping, along with Truman Capote to create a new sub-genre of literature called New Journalism. Mailer wrote the story of Gary Gilmore, the first American executed by the state in ten years, bringing back capital punishment. He wrote the story as though it were a novel and captivated the country. He was a creator in the sense the genre had not been in existence until he spoke it. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize twice and the National Book Award once. Mailer died on this day in 2007.

Remembering Norman Mailer is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 9, 2011

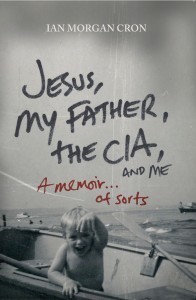

Excerpt from "Jesus, My Father, the CIA, and Me: A Memoir…Of Sorts" by Ian Morgan Cron

This week's guest post is an excerpt from Ian Morgan Cron's acclaimed book Jesus, My Father, the CIA, and Me: A Memoir…of Sorts. Seriously, it's acclaimed. It has 101 5-star reviews on Amazon, and Publishers Weekly called it "Redemptive and consoling with bright moments of humor…this story is chock-full of sacredness and hope. Cron is one of only a few spirituality authors who could articulate these themes as poignantly." Ian is also the author of Chasing Francis: A Pilgrim's Tale, spoke at the Storyline Conference last spring, and is currently completing his doctorate at Fordham University in Christian spirituality. You can visit him at IanCron.com and follow him on Twitter here.

This week's guest post is an excerpt from Ian Morgan Cron's acclaimed book Jesus, My Father, the CIA, and Me: A Memoir…of Sorts. Seriously, it's acclaimed. It has 101 5-star reviews on Amazon, and Publishers Weekly called it "Redemptive and consoling with bright moments of humor…this story is chock-full of sacredness and hope. Cron is one of only a few spirituality authors who could articulate these themes as poignantly." Ian is also the author of Chasing Francis: A Pilgrim's Tale, spoke at the Storyline Conference last spring, and is currently completing his doctorate at Fordham University in Christian spirituality. You can visit him at IanCron.com and follow him on Twitter here.

***

My fellow first graders and I processed down the nave to receive our First Communion while a woman sang "Ave Maria" with a vibrato that could have been picked up on police radar. I remember almost nothing of the Mass itself except Bishop Dalrymple distributing the consecrated Hosts. He was corpulent, his cheeks and jowls glazed with perspiration, and he was lightly wheezing. He looked like he would have paid a hundred bucks to get out of his clericals, go home, put his tired feet up, pop open a cold Bud, and watch a Notre Dame basketball game.

As I stepped forward and stood before him, he saw tears welling up in my eyes. For an instant, Bishop Dalrymple's pasty white face softened, the corners of his mouth turned upward in a smile of deep knowing. I suspect he knew that I was one of those strange kids who "got it"— who was hungry and thirsty for God, who longed to be full. Maybe he'd been one of those weird kids too. He placed the Host on my tongue and put his hand on the side of my face, his fat thumb briefly massaging my temple, a gesture of blessing I did not see him offer to any of my other classmates. And I fell into God.

I have spent forty years living the result of that moment.

I am told that, in years past, when a blizzard hit the Great Plains, farmers would sometimes tie one end of a rope to the back door of their farmhouses and the other around their waists as a precaution before going out to the barn to tend to the animals. They knew the stories of farmers who, on the way back to the house from the barn in a whiteout, had become disoriented and couldn't find their way back home. They would wander off, and their half-frozen bodies wouldn't be found until spring, when the snow melted.

That day, Bishop Dalrymple, sweat dripping from the end of his bulbous nose, tied a rope around my waist that was long and enduring. How did he know the number of times that I would stretch that rope to its breaking point or how often I would drift onto the plains in a whiteout and need a way to find my way back home?

A few weeks after my First Communion, I came home from school and my mother told me that my father had gone on a last-minute business trip to Northern Ireland. This was a surprise since I didn't know my severely alcoholic father was employed.

He didn't come home for six months.

I learned years later that this was the year the "troubles" broke out between pro-British Unionists and pro-Irish Nationalists. I'm certain he was there on assignment for the CIA.

I have a postcard he sent me from Belfast on which he wrote, "Do you want to know a secret? I love you."

I would have given anything for my father's love to not be a secret. Anything. A boy needs a father to show him how to be in the world. He needs to be given swagger, taught how to read a map so that he can recognize the roads that lead to life and the paths that lead to death, how to know what love requires, and where to find steel in the heart when life makes demands on us that are greater than we think we can endure. A young boy needs a father who tells him that life is a loaner, who helps him discover why God sent him to this troubled earth so he doesn't die without having tried to make it better.

He may not know it, but from the moment he first glimpses his baby boy's head crowning in the delivery room, a father makes a vow that with stumbling determination, he will try to get a few of these things right. Boys with fathers who keep their love undisclosed, go through life banging from guardrail to guardrail, trying to determine why our fathers kept their love nameless, as if ashamed.

We know each other when we meet.

Excerpt from "Jesus, My Father, the CIA, and Me: A Memoir…Of Sorts" by Ian Morgan Cron is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 8, 2011

Why Questions

I wonder what it must feel like, for those without a faith system, to wake up one morning and suddenly ask why questions. I would think it would be difficult to explain pain and suffering, to explain beauty and meaning and purpose with only subjectivity as framework. When I think of this, I think of that Douglas Coupland book with all the nursery rhyme characters who are lost, looking for something good that was supposed to happen but never happens because the plastic surgery didn't work or the drugs started to own them or the depression that is always, always waiting just outside the door found a crack it could slip through to whisper hard and unwanted truths into the ears of the characters whose stories were supposed to come true, were supposed to end with a happily ever after. And I wonder, quite honestly, if I will end up like this, if I will discover that my Christian faith, my American faith, was a fraud, and that there was nothing behind it, that it wasn't even pointing me toward something real and authentic, and I, too, will join the ranks of the dispossessed, staring up into the cosmos asking why, only to have the cosmos shrug its broad black shoulders as if to return the question.

I wonder what it must feel like, for those without a faith system, to wake up one morning and suddenly ask why questions. I would think it would be difficult to explain pain and suffering, to explain beauty and meaning and purpose with only subjectivity as framework. When I think of this, I think of that Douglas Coupland book with all the nursery rhyme characters who are lost, looking for something good that was supposed to happen but never happens because the plastic surgery didn't work or the drugs started to own them or the depression that is always, always waiting just outside the door found a crack it could slip through to whisper hard and unwanted truths into the ears of the characters whose stories were supposed to come true, were supposed to end with a happily ever after. And I wonder, quite honestly, if I will end up like this, if I will discover that my Christian faith, my American faith, was a fraud, and that there was nothing behind it, that it wasn't even pointing me toward something real and authentic, and I, too, will join the ranks of the dispossessed, staring up into the cosmos asking why, only to have the cosmos shrug its broad black shoulders as if to return the question.

I would imagine having the capacity to ask why questions but not having any answers would just make life feel something like rehab.

This passage was an excerpt from Through Painted Deserts.

Why Questions is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 7, 2011

The Truth Is There Are a Million Steps

I know there are people who have actually gone from misery to happiness, but they didn't do it by walking through three steps; they did it because they had a certain set of parents and heard a certain song and knew somebody who had a certain experience and saw some movie, read some book, had something happen to them like a car wreck or a trip to Seattle. Then they called on God, and a week later read something in a magazine or met a girl in Wichita, and when all this had happened they had an epiphany, and somebody may have helped them fulfill what this epiphany made them feel, and several years later they rationalized this mystic experience with three steps, then they told the three steps to us in a book. I'm not saying they weren't trying to be helpful; I bring this up only because life is complex, and the idea that you can break it down or fix it in a few steps is rather silly.

I know there are people who have actually gone from misery to happiness, but they didn't do it by walking through three steps; they did it because they had a certain set of parents and heard a certain song and knew somebody who had a certain experience and saw some movie, read some book, had something happen to them like a car wreck or a trip to Seattle. Then they called on God, and a week later read something in a magazine or met a girl in Wichita, and when all this had happened they had an epiphany, and somebody may have helped them fulfill what this epiphany made them feel, and several years later they rationalized this mystic experience with three steps, then they told the three steps to us in a book. I'm not saying they weren't trying to be helpful; I bring this up only because life is complex, and the idea that you can break it down or fix it in a few steps is rather silly.

The truth is there are a million steps, and we don't even know what the steps are, and worse, at any given moment we may not be willing or even able to take them; and still worse, they are different for you and me and they are always changing. I have come to believe the sooner we find this truth beautiful, the sooner we will fall in love with the God who keeps shaking things up, keeps changing the path, keeps rocking the boat to test our faith in Him, teaching us to not rely on easy answers, bullet points, magic mantras, or genies in lamps, but rather rely on His guidance, His existence, His mercy, and His love.

Personally, I was miserable before I understood these ideas, but now I am so happy I laugh all the time, even in my sleep.

This passage was excerpted from Searching For God Knows What.

The Truth Is There Are a Million Steps is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 6, 2011

Sunday Morning Music: Florence + the Machines

Today's Sunday Morning Music is "Shake It Out", the first single off Florence + the Machine's new album, Ceremonials. It's a big, loud track, and I've been listening to it incessantly all week.

Sunday Morning Music: Florence + the Machines is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

November 2, 2011

Reconciling Revenge

Today's guest post is from me, Jordan Green, the guy posting these guest posts. You can follow me on Twitter.

I would generally consider myself a pacifist. I say "generally", because I don't really know how I'd react in a given situation. If, for instance, a crazed hobo woman attacked my daughter, I'm fairly certain I would resort to physical violence in order to get her to stop. So maybe I'm a pacifist when it comes to larger communities, like nation-states and youth groups. Because of my semi-pacifist philosophy, I've always had one major hang-up with narrative morality, an idea this blog's esteemed owner discusses in A Million Miles in a Thousand Years. That hang-up is this: when played out in story, revenge is sort of awesome.

For instance, I'm reading through George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire series right now, and there are plenty of characters in this epic, sprawling fantasy series who I want to pay. And I don't want them merely brought to justice in a court of law and imprisoned for life. They are evil people, and I want them to die the most painful deaths possible. Most of them do end up dying horrific deaths, simply because (SPOILER ALERT) a lot of people die in these books.(END SPOILER ALERT)

Of course, the characters in Martin's novels aren't real, but real life has its share of bad guys. The latter half of the 20th century seemed to mark a turn away from Old Testament-style justice. Adolph Hitler: committed suicide to avoid capture by the Red Army. Joseph Stalin: died of a cerebral hemorrhage at 74. Pol Pot: died at home of a heart attack. Slobodan Milosevic: heart attack while under trial for war crimes. Saddam Hussein: hanged after being convicted for crimes against humanity. The point is, the deaths of some of the 20th century's worst people were decidedly unlike that of your average Bond villain.

Then, in the last six months, Osama Bin Laden and Muammar Gaddafi died extremely violent deaths. The former, of course, was shot in the head during a raid by US forces. The latter was captured in a hole, beaten viciously, and, according to some reports, took around 30 minutes to die after being shot in the head and chest.

Now, I know I am supposed to love my enemies, to pray for them and even bless them. I know this because it is discussed pointedly in Romans, Luke, 1 Peter and 1 John. But what's curious to me is how these deaths feel to me from a purely narrative standpoint. And, if I'm honest, the deaths of Osama Bin Laden and Muammar Gaddafi feel somewhat…well…right. As much as I tell myself the death of a human being should never be celebrated, I do at least feel some satisfaction knowing these men are gone. Gaddafi was a madman who ruled with an iron hand, who lived in unchecked opulence while his people suffered. Osama Bin Laden was Osama Bin Laden. One of the key components of Protestant Christianity is the belief we do not get what we deserve, that through following Christ all sin is absolved, but there is still a very real part of us that wants to see certain people get what's coming to them, from cruel despots to schoolyard bullies. If narrative morality is ingrained in us by our creator — and I think for the most part it is — why is vengeance so undeniably gratifying?

The easiest answer is to say we want justice, and that's partly true. We yearn for God to put the world right. But there's more to it than that. One of my favorite stories takes place in Corrie Ten Boom's book Tramp for the Lord. Ms. Ten Boom is lecturing in Germany when she is approached by a man whom she quickly recognizes as a particularly brutal Ravensbruck guard. Before he can speak, she forgives him:

"For a long moment, we grasped each other's hands, the former guard and the former prisoner. I had never known God's love so intensely as I did then."

What we truly want is for villains to repent. Ideally, we want a villain to understand what he did was wrong, and redeem his horrible actions. When that doesn't suffice, we want him to realize he was not as powerful as he thought. This is why, when a villain dies in a story, we are shown his reaction one last time as he plummets to his death or realizes a bomb is about to explode. We want to see him recognize he is a broken man.

The question from there is whether we want our villains forgiven, and I suspect that's a matter of perspective. Did anyone really want Die Hard to end with John McClane forgiving Hans Gruber, grasping hands, and experiencing God's love? Doubtful, but this is partly because Hans Gruber is not a real human. He's an avatar for evil. Real people are a lot messier, with compounding factors like traumatic childhood experiences and mental illness.

Like all sin, we each have our limits. The tools God gives us to push those limits — empathy and a willingness to cede control of our lives — are crucial in determining our reactions. If I had known Muammar Gaddafi, or Osama Bin Laden, I wonder if that glimmer of satisfaction I felt would've been diminished completely, and a story read as justice served would more closely resemble a tragedy.

Reconciling Revenge is a post from: Donald Miller's Blog

Donald Miller's Blog

- Donald Miller's profile

- 2745 followers