Daniel M. Bensen's Blog, page 91

April 2, 2015

Quantum Europe

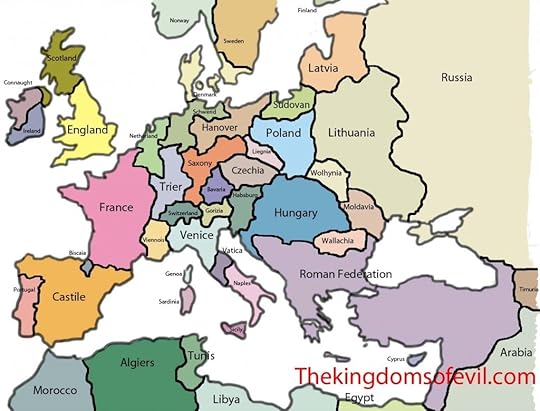

Browsing alternate history maps like you do, and I got to wondering. Of course the borders in a given area (say Europe) depend a lot on historical contingency, the arbitrary choices of leaders, and plain old accident, but geography plays a role, too. Unless your alternate history is very alternate indeed, mountains and rivers still function the same way to hinder or aid armies and merchants. So given this geography, what state borders are most likely?

I went to Euratlas Periodis and its series of historical maps of Europe. Then I popped an entertaining audiobook into my ipod and started tracing the little black lines between 1000 and 2000 CE. Here’s what I got.

A few borders have remained relatively unchanged for the past thousand years: Portugal assumed its present shape during the Reconquista and stuck that way, and France has never managed (or wanted?) to cross the Pyrenees. The Eurasian Steppe is usually occupied by some large state or other, everybody wants a piece of coastline, and Central Europe is just a mess. Focus on only those long-lived borders, and you get:

Quantum Europe!

…in other words a smear of the last thousand years of history.

I’m not sure what series of events might have lead to such a map in the 20th century. Constantinople ascendant over Rome? The absence of Charlemagne? Christian Mongols? A more severe Black Plague? Or maybe we can blame those dang-blurned Protestants, taking over Western Europe and telling rival royal families not to marry each other? What do you think happened?

March 31, 2015

Charming Lies chapter 1

Here’s the first chapter of Charming Lies, the historical fantasy currently in need of beta-readers! Comment below if you’re interested.

The bare branches of the oaks striped Elena’s hands with shadow as she cast the rings.

“Who will be betrothed, herself?” She called.

“She will be betrothed!” The girls of Gyulovo gave the response. Some of them were older than Elena. Elena should be part of this year’s crop of maidens, not presiding over them like some sort of witch queen.

What a tempting prospect. A corner of Elena’s mouth tightened as she looked down. Wooden, oiled to gleaming, and incised with the notches and grooves of Elena’s craft, the rings bobbed around her hooked fingertips.

“Blood sausage on the shelf,” Elena recited. “Who is mine? Who will I marry this year?”

“A swineherd!”

Elena managed to hook a ring with her little finger, careful not to touch the edges. Sodden with water, the grooves carved into its surface didn’t have the same compelling power as when dry, but one didn’t become a witch by taking foolish chances with art.

The owner of the first ring didn’t seem to mind her smelly fate, nor did she take proper care when she plucked the ring from Elena’s finger.

“Don’t touch the carved parts,” whispered Elena. “They’re ensensed,” but the girl grasped the ring and shivered in pleasure and terror.

Fools. They shy away from my fingers, but play with the amulets I carve for them as if they were just wood and metal.

Elena watched the girl unconsciously run her fingers over the ring again, layering compulsion into her minds. I could make her do anything. Kill herself. Kill her betrothed. Grind him into blood sausage.

The other girls were watching her. Elena looked down at the little wooden rings bobbing helplessly in the silver water. She gave them a splash and fished out the second one. “A tit knocks at the mill,” went the second verse of the Casting of the Rings. “Who is mine?”

“A miller!”

And so on.

The next girl managed to retrieve her ring without accidentally casting a spell on herself.

“Sparks fly in the fireplace. Who is mine?”

“A blacksmith.”

“A crouched dog on a white stone. Who is mine?” Elena sang. Response: “A shepherd!”

She fished for the next ring and tried to remember the next verse. Ah, yes. “Through the hollows he runs, tightening his sandals. Who is mine?”

“A bandit!” sang the other girls, but their giggles choked off when the ring’s owner stepped out from between her bodyguards and put out a slender hand to claim her fortune.

“A bandit?” Selime hissed as she reached for her ring.

“Don’t blame me,” said Elena. “You’re the one who wanted to sample our quaint Bulgarian customs.”

“Be that as it may, there was no cause for you to betroth me to a villainous outlaw.”

“Your ring just came to my fingers,” said Elena. “Like fate.”

Selime’s expression as she took the ring was faintly amused, but the Turkish lady’s agitation showed in the way she tugged at her rich vest and skirt, straightened the plate-sized silver clasps on her belt. Shadows and light chased across those gleaming surfaces, catching the eye, ensnaring the mind.

Heed me, the charm commanded, far more powerfully than anything in the village girls’ costumes, respect me. Bow your head when I approach.

“Make sure to flash those ornaments at your bandit husband when you meet him,” she said, her backbone reinforced. “You should begin things as you mean to go on. And if he somehow manages to get within striking distance…”

She plucked the last ring, her own, out of the water and slid it onto the third finger of her right hand. “Touch this pattern to your man’s skin and he will desire you.” She turned her hand. “Touch this pattern to his skin, and he will fear you. You can control him with a slap, or,” she mimed the motion, “a caress.”

“A most…efficient addition to the ritual.” Selime spoke Bulgarian with little accent, heavily laced with high-sounding Turkish words. “But it comes to my attention that you have not sung the verse for your own ring, Elena-m.”

“Oh.” Elena searched her memory as the other girls giggled. “The one about not marrying?”

“No,” said the carter’s daughter, the one fated to marry a swineherd. “That’s the next verse.”

There was some discussion about what that verse should be until the answer emerged: “Yours is ‘Quiet water over stones. Who is mine?'”

“A gentle man,” Elena blinked. “Well, if I manage to find one, I won’t have much need of this ring, will I?”

“As if such were ever necessary for you, canım,” said Selime. “My dear friend and witch, you make the poor boys’ hearts burst with a twitch of your fingers.”

“A habit I’m trying to cure,” said Elena. “Bad for repeat business. Speaking of which…” She held her be-ringed hand out for the others to see. “The amulet will only work as long as he’s touching it. Unless you want to strap the ring to him, you will need more effort to pass through the door its charm opens.”

But the girls weren’t listening. They nodded and smiled and drifted off in twos and threes out of the forest and onto the road that led back into town.

“Damn,” said Selime. “It’s my presence that is making them uncomfortable.”

“No, it’s mine.” Elena clenched her fingers around her ring. Feel fear. “They don’t want to learn charm. They’d rather be helpless and small, unnoticed.” Now more than ever.

Elena wished she had thought to ensense those rings with more compulsion than simply fear and pleasure. What if she had added something to the inner surface? Stand up for yourself. Or even just listen to Elena.

Selime cleared her throat. “We should also be returning.” She reached up to touch her two grinning guards. “Take me home, boys. Eve.”

“Eve,” they echoed, and lurched into motion.

Elena watched the two un-men, wishing she didn’t have to follow them. Wishing she could turn east instead of west and travel to some village where she wasn’t the stepdaughter of the enfumist or under shadow the of the Kadii and his plans. She rubbed the outer edge of her ring.

Feel fear.

Elena had vowed at last year’s Casting of the Rings to leave this rose-scented backwater. But then her mother had died. The priest had vanished from his little chapel. The tension between Selime’s father and her step-father had turned ugly. A lot had turned ugly. And there was nobody with the power to solve the problem who wasn’t part of it.

The Kadii might yank the chains of the sultan’s legal and holy authority, but Kostadin the enfumist, whispered in the ears of every shepherd and farmer. And when whispers didn’t work, there were always his perfumes.

“It’s just an old drinking horn you father had dug out of the mound in old Misho’s field,” Elena said with as much dismissal as she could fake. She’d never seen the artifact, but she knew it slit the mind up the middle. Anyone could slide a hand into that gap and operate the meat of the body like a puppet. An automaton.

“You don’t know what my father does with it?” Selime’s eyes darted to first one, then the other of her grinning guards. They had stopped when she did, and now stared into space, expressions of ecstatic pleasure on their faces.

Elena decided to employ honesty. “I want to understand why the charm doesn’t wear off. These men,” she waved at them, “these un-men—”

“Otomatlar is the technical word,” said Selime. “Automatons.”

“These automatons,” said Elena, “fine. They’re out here and the drinking horn is in your father’s treasury.”

“And there it will stay.”

“Yes. It will stay there.” Elena held her arms out to her friend. “I promise, Selime—”

A leather-clad arm snapped down in front of her. “Do not get too close to the hanım. You are too close to the hanım.”

“Peace,” said Selime in Turkish, “peace, you useless, lumbering impediments. Eve! We are going home, remember?”

She stepped down the embankment and the automatons jerked into motion behind her. “Can’t we speak about something pleasant while we walk home, Elena-m?”

Like how my step-father is planning to overthrow your father? Thought Elena, and whether I stop him or help him, half the people in town will be killed. Beginning with the two of us?

She had to tell Selime. She couldn’t tell Selime. Elena could only gather as much power as possible and hope that when the time came it would be enough. “I swear to God above that the Rhyton will not leave the treasury,” she said. “I just want to look at it.”

“You just want to steal its power.”

“You can’t steal power from an amulet,” she said.

“Copy it then,” said Selime. “You want to copy the curse of the Thracian Rhyton. You want its power. You’re always,” Selime stuck out her hands, fingers curled into claws, “grasping for more power.”

Selime’s foot sunk into a puddle and she swore. “You, there. Guard One. Carry me to the road. Carry me.”

The automaton blinked at her smiling for a few moments before awkwardly bending at the waist and holding out his arms. Selime climbed into his embrace as if into a cart. “Go,” she ordered, and the automatons went.

Elena followed her friend keeping well away from the body-guards. What compelled them to ignore their own interests in favor of their mistress’s orders? And what might she do with such servitors herself? She needed that Rhyton.

Elena was formulating her next argument when her ears pricked.

“I see someone coming,” said Selime from the road. “A large party, too. They must either be very early merchants on their way to Sofia or…Ah.” Selime put her hand to her mouth. “Those must be the new levies my father ordered.”

Elena backed further away from the road into the shadows. “New levies.” She said the words in Bulgarian, but Selime had used Turkish: yeni çeriler.

Muskets clattering, sabers rattling in the rhythm of their marching song, the janissaries closed on them. They wore their field uniforms, with their brass spoons sticking up like feathers from the brims of their folded-over felt hats, knee-length caftan-coats, and baggy savlar pants billowing out of their woolen leggings, which were in turn stuffed into iron-heeled ankle boots. Their faces, dark and light, wide and narrow, long-nosed and short, bearded, mustachioed, or clean-shaven, all bore identical, grim expressions. Their eyes stared blankly ahead, lost in the charm of their marching song.

At the head of the column marched the captain, chanting in one-two rhythm and leading a mule carrying a large, bearded man in the robe of a cleric. The captain saw Selime and raised his hand as he slowed his pace. “Merhaba, hanım-effendi,” followed by something too fast and formal for Elena to understand. She caught the word Konak, though, and figured the janissary had offered to escort the Kadii’s daughter back to his residence. These men were not simply passing through.

Janissaries. New soldiers that the Kadii had ordered? What was he planning to do with them? What was he planning to do with them and the Thracian Rhyton in his treasury? The cursed relic which turned healthy, strong young men into mindless and obedient servants?

They hadn’t seen her yet. She could stay here in the woods until the soldiers passed and…what? Go to her step-father and let him whip the village into bloody revolt? Or let yet more tools fall into the hands of the Kadii.

Elena looked back into the forest, where scrawny saplings twisted in their attempts to dodge the shadows cast by the larger trees. If one of them should fall, there will be more light for the new trees. She breathed in the spring air, complex and alive with the smells of growth. If only I can get my hands on the right axe.

“Selime, wait for me.” Elena strode out of the shadows to take control of the situation.

She was brought up short by a wall of blue wool.

The janissary captain was very tall. His heavy eyebrows lowered over large, dark eyes and his hand tightened around the hilt of his saber. Under the straight black lines of mustache, his lips formed an O as if to whistle in approval.

Timurhan bin Metin glared into the face of the village girl, hand ready to draw his saber, lips ready to enchant her. “Who are you? A servitor of the lady?”

“Elena sam,” she said, and Timurhan found his sword arm pressed against his body by a soft mass of female flesh.

Hold still.

Timurhan tried to step back, to clear his sword, to whistle an enchantment, anything, but his body was no longer his to command. The girl fitted herself more snuggly against him.

Focus on this sensation.

Her body heated his through the layers of their clothing, but her fingers were cool as they traced down his right arm toward the bare skin of his sword-hand. Cool and firm and very nice.

Feel pleasure and be compelled.

His vision swam.

See the imposing janissary captain, marching into the teeth of a trap. See a man in a Kadii’s robes, holding forth a drinking horn of ancient design.

Timurhan could not push her away. He could not even try. She felt so good.

See the captain drinking, and all is black. See the captain turn away, blank-eyed and grinning.

The compulsion of her body immobilized his arm. Hallucinations filled his eyes. But with a shove of will, Timurhan managed to purse his lips. To breathe.

The whistle wavered, found its note, steadied itself, and became music. A simple, sweet tune, sure to catch the ear and burrow inside. Sure to carry Timurhan’s compulsion past the defenses of whatever minds were so unfortunate as to be within earshot.

Hold still, he enchanted them. Listen to the music. Be compelled. Now step away from me.

The hallucination evaporated and Timurhan could once again see the witch who had ensensed him. She was backing away from him, along with his men and the lady Selime. He could not compel his men to seize the ensensoress, she would gain control over them as soon as they touched her. A suicide enchantment would affect everyone in earshot. He could compel his audience to stone the witch, or he could simply run her through with his saber. He ought to. The witch had dared to ensense him. And yet…

What had she done, but warn him?

Timurhan tore through the fading memory of her skin on his and forced his body to move. He bowed.

“My apologies, servant, for enchanting you. But you know you should never accidentally stumble into a janissary. Someone might think you were trying to use compulsion on me.”

Her brows furrowed. She looked down at her hands, up at the half dozen now very suspicious soldiers staring at her.

Timurhan wondered if she even understood his words. “We are not enemies,” he said. “Yes? We are friends. We are servants of the Sultan.” Hand on the hilt of his saber, he leaned toward her, dropping his voice. “We kill enemies of the sultan.”

She fiddled with a wooden ring on her right hand and looked back up into his eyes. Her face was sharp and rather narrow, with a long, pointed nose and narrow lips. She did not look particularly intimidated. Nor, indeed grateful. “Da ne bi da si krotak mazh?”

“What did you say?”

There was a genteel cough from the lady. “Krotak means ‘tender or gentle, mazh means ‘man’ Selime raised an eyebrow ‘or husband.'”

“I…see.” With some effort, Timurhan broke eye contact with the native and addressed her mistress. “Do I have the honor of addressing the daughter of the magistrate of this village?”

She nodded. “I am Selime, daughter of his honor Ali. May I ask your name, sir?”

“Captain Timurhan, my lady.” There was no need to lie about his name this far from Istanbul, only his mission. “Sent here to lend my service to your father.”

“Of course you are.” She nodded, sunlight flashing on her earrings and necklaces.

Respect me.

Every article of clothing, from Selime’s headscarf to her slippers, compelled the viewer to step back, stay away, keep hands off. That was entirely natural for a respectable daughter of wealth in Istanbul. Here, however, on this pimple on the armpit of the Ottoman Empire, such elaborate armor struck a suspicious note. And then of course there were her automatic bodyguards.

Timurhan recognized the men. Or the men they had once been.

As if the witch’s warning weren’t enough. We have certainly come to the right place.

“So,” Timurhan said to the girl whose father he had been sent all this way to execute, “how may we be of service?”

“You may escort me to the mansion,” Selime turned, flanked by her automatons.

Elena turned as well, but looked back over her shoulder at Timurhan, dark eyes flashing.

The corners of Timurhan’s mouth twitched.

“God is great,” Mustafa Sokollu, enscriptor and most skilled of the masters of arms of the Hagia Irene, leaned across his mule and spoke in a voice too low for the women to hear. “She’s looking at you the way you examine a new bow. Wondering about your range, perhaps or your pull?”

“Come along,” ordered the lady Selime. Timurhan remembered his role and nodded smartly, raising his hand and whistling.

The tune he chose was a simple one. A marching song, of course, about a lovers separated by siege. And what would happen when the walls broke. The men loved it, and their minds and bodies became his to control.

“What happened back there?”

Mustafa bent toward Timurhan and nearly overbalanced his poor mule. The experimental artisan was a hazard to horses. And to himself if he needed to pass under a low doorway. Mustafa was enormous, with a red beard that had led one Istanbul wag to compare him to a hill in autumn. Mustafa had written out that witticism in a calligraphic enscription that compelled the reader to pick his nose and belch. Timurhan couldn’t remember the poet’s retaliation. Probably something equally disgusting.

“Well?”

“You saw it,” said Timurhan, his hand still humming with memory of her touch. “She slipped and fell against me.”

“She ensenssed you.”

“She did not compel me to do anything.”

“I saw your pupils dilate,” Mustafa said.

Timurhan glanced sidelong at his friend. “She compelled me to see a vision. Tried to warn me about this town and its magistrate.”

They paused to let pass a flock of sheep, only slightly more shaggy and disreputable-looking than their shepherd.

“All the same,” said Mustafa. “She ensensed you and you let her just walk.”

“I did not think it necessary to kill the woman.”

“The fact that she is a woman makes no difference,” said Mustafa. “The most potent weapons are carried in the mind and do not need a soldier’s burly arm to wield. Remember that ensensoress in Shiraz?”

Timurhan smiled. “The one with the foot massage? I always thought it an ingenious mode of assassination. That witch could not defeat me, and nor will this one.”

“The witch in Shiraz did not have breasts like pomegranates, thighs like a camel, or calves like two ivory columns.”

Timurhan watched Elena’s back. “It’s lines like that that make me wonder if the Persian poets ever actually felt a pomegranate or saw a camel.”

“Or a woman, for that matter.”

The village, once they reached it, was really nothing more than a bend in the river. The Magistrate’s administrative center and a few merchant’s houses looked barely more luxurious than the peasant shacks. Chickens, dogs, and stray children joined the sheep and goats in their efforts to slow Timurhan’s platoon and coat his boots with offal.

“There isn’t even a mosque,” said Mustafa. “One presumes the local magistrate simply leans out of his balcony every morning and yells wake up at his subjects.”

“And we’re expected to dine with this man before we kill him?”

“I’m rather looking forward to it.”

Timurhan grimaced. A stitch was forming up his left lower back. “I doubt we can expect scintillating dinner conversation from him. He’s been driven mad by the curse of a Thracian tomb.”

“Preposterous,” said Mustafa. “We can make a man angry or covetous, as long as he holds the right ensensed amulets. We can automatize him—stuff a logic tree into his head and hope it’s big enough to allow him to navigate a room unaided. We can take up his strings and operate him like a marionette, but even at the Irene Workshop, the best and most advanced workshop in the world, we can’t change one man into another.” He snorted. “Not from beyond the grave, certainly.”

No doubt Mustafa was right, and the magistrate was just corrupt and treasonous, not the pawn in a game of undead eldritch powers. All of which made Timurhan wonder why he was going through so much trouble. He smoothed his hands down the buttons of his jacket, feeling all his borrowed janissary uniform’s deficiencies and deformities. A good old cavalier’s cloak would sweep impressively behind him. And his real helmet had a plume in it, not this stupid brass spoon he had strapped to his janissary’s hat. Spoons! Honestly, what was wrong with the Conscript Corps? And his boots were just disgusting.

Timurhan looked with hot envy at the gleaming footwear of Mustafa, perched smugly atop his mule. “There’s no reason we had to come here on false pretenses,” he said again. “Just ride into town, kill everyone who needs killing, and leave. It’s always worked for me before.”

“This time won’t be like before,” said Mustafa, also not for the first time. “I have reason to believe the magistrate here has got his hands on something truly powerful. And he has the education to make use of it.”

After his vision, Timurhan couldn’t exactly argue.

“So this vision she showed you,” Mustafa pressed. “Did it tell us anything we didn’t already know?”

“The nature of the charm that they use to automatize men,” said Timurhan. “It’s an artifact. A golden drinking horn shaped like a sheep’s head.”

“Sounds Thracian,” Mustafa stroked his beard. “Perhaps they dug it out of a tomb.”

“It’s nice to know we’ve already completed the first task of our mission,” said Timurhan.

“As if we required any further proof that this is the center of the recent disturbances. Thefts, raids, mysterious travelers, lights on the burial mounds at night. Taxes paid suspiciously on time.”

“Missing soldiers,” said Timurhan. Gyulovo had swallowed up two platoons of irregular troops already, two of whom had become the grinning guards of the lady Selime. Timurhan hoped her death would not be necessary. Nor that of her serving girl.

Timurhan considered the witch. Elena. The thick braids of black hair swinging under her dark green shawl. Her skirts were more or less the same color, as was the vest. Her breasts, as Timurhan vividly recalled, were proud and generous, and deliciously soft under confines of the vest and billowy undershirt. There was none of her mistress’s charmal armor. Nothing to stop him from freeing that magnificent bust from the cruel confines of her clothing.

Timurhan would do just that. After he’d killed the renegade magistrate and brought down his evil schemes, of course. With Timurhan’s special talents, his new saber, and Mustafa’s support, he should be done with the mission by evening. And with her cruel oppressors dead, Elena should feel grateful indeed.

“You’re thinking of her, aren’t you?”

Timurhan turned a frown on his friend. Maybe he could start this mission by rescuing the mule from Mustafa’s oppressive buttocks. “Merciful God, man. Sit up and try to sway with the mule. You look like you’re punishing it for not being a bed.”

“Bed!” Mustafa groaned and shifted his weight. The mule groaned, too. “The very word has become foreign to me. Do you think the magistrate will let us take a nap before—”

“He tries to murder us?”

“I was going to say, ‘before dinner.’ And he won’t try to kill us, he’ll try to enslave our wills to his.”

Timurhan watched Selime’s automatons. Their movements were smoother than any such creature he’d seen in Istanbul, but their face bore the most disturbing expression.

“I’d say a man with no will of his own is dead,” he decided, “even if he’s up and walking around.”

“A nice philosophical point,” said Mustafa, “but consider what binds your will now. Would you be in this damp backwater if our sultan hadn’t ordered it?”

“That’s the whole point of loyalty,” said Timurhan. “If I was compelled to come here, my actions would be meaningless.”

“For you if not for the one who compelled you.” A thought seemed to strike Mustafa. “But consider: what if the one who compelled you was himself compelled? What if everyone were compelled to compel others in turn? An empire of automatons.”

Timurhan drew his lips back in disgust. “An empire of the walking dead.”

“Well, one may be cured of automatization,” said Mustafa. “Not so much death.”

“Cured in theory,” said Timurhan. “But if you command automatic troops, what’s the first thing you throw at a real soldier when he shows up?” Timurhan spread his hand over his own chest. “Automatization is a death sentence. At least when I am in the area.”

7th Mother

Sorry, no April Fool’s joke this year.

But remember last week when I talked about making the 7th-son-of-a-7th-son fantasy trope make sense as a system? Well, it turns out I didn’t go nearly far enough. Flesh-Pocket, Melissa Walshe, and Peter Queckenstedt, and I fleshed out the mechanism for birth-order-dependent thaumaturism that generates all sorts of new and interesting problems.

Let’s say there’s an epigenetic factor (some kind of methylation?) that up-regulates magical ability with each successive pregnancy. The children of those pregnancies get more and more magical, and (if they’re women) they pass that magic along to their children in addition to their own methylation for THEIR successive pregnancies. After a certain number of iterations, the seventh child of a seventh daughter would pass some critical threshold and present as a sorcerer or sorceress. Boys might express magic, but they can’t pass it on.

There’s got to be a catch, though. The only reason a system like this would evolve is if the selective advantage of magic balances out some other disadvantage. Otherwise, everyone would be maximally magical. Perhaps magic comes at such a high metabolic cost that using it basically cripples you. So you have to have all of your six older siblings taking care of you to have any hope of survival. Of course you can fudge things by using medical magic to increase the chance that the child survives, but you run into diminishing returns there, too. 7th child of a 7th mother is where diminishing health and increasing magical ability balance out.

This flips the assumptions we make about medieval family-size, gender roles, and class. All women aristocrats will be expected to have at least seven children, but for commoners, having large families will be treasonous. Can’t have the peasants producing their own hedge-witches, after all.

Of course there’s no way to enforce small family size on the peasantry by law alone. Enforcing those laws means pissing people off enough that they’ll want to hurry up and produce a hedge-witch to overthrow you. The only way for feudal monarchs to make sure their peseants don’t over-reproduce is to make them work for money instead of farm for subsistence, using magic rather than mechanization to impose an industrial revolution and a demographic transition. So 7th Mother society will look a lot like our own, with social pressure for women to work and not have many children. Rebels will be the ones who hide their pregnancies and give birth in the basement.

Imagine a wheelchair-bound sorceress in her tower, waited on by jealous older siblings. A trivially magical 6ths son of a 5th daughter with no prospects sent out to seek his fortunes by invading neighboring kingdoms (who also have their own sorcerers). A common-born Chosen One produced to lead a rebel army and right wrongs that happened two generations ago, locked away from sight since infancy and trained as a child soldier. Welcome to the world of the 7th Mother.

March 29, 2015

Teenager Conlang

http://danbensen.tumblr.com/post/112692988201/excessunrated-phonetic-description-of-annoying

March 26, 2015

X^xth Son

Imagine a world in which being the seventh son of a seventh son (or whatever combination of number and gender) reliably made you magical. The result wouldn’t be as awful as a “magic gene,” a la Star Wars, but it would still do some pretty weird things to human evolution, not to mention society.

I imagine there would be a pretty high selective advantage for fecundity, and kin selection would play a role too, with the non-magical siblings of the magic Xth child being granted advantage due to their magical largess. Outside kinship circles, though, competition would be intense, with everyone scrambling for the resources necessary to produce the proper number of kids. And what do you do with all those excess kids?

I’m thinking small constantly feuding agrarians, periodically united/oppressed under ferocious “witch-kings.” Fun!

March 25, 2015

3 Dimensions of goal-orientation

There are few better feelings than getting an email from Arianne “Tex” Thompson.

Zzz! Goes my phone, and to the right of the unopened letter icon, there’s a line of text (in bold!) that says something like Schedulations! or The Conclave of Ēostre or Skype Gripe.

My finger hovers over the icon. I press it and my phone grows hot in my hand. Like really hot. It also runs through like an entire night’s worth of charge in half an hour. That’s not normal, right? I should see someone about that.

But anyway. Tex’s email. There were too many crazy good ideas in it for me to talk about all of them here, so I’m just going to focus on the model we created for making goals (and writing books). Check out Tex’s half of the conversation for using social media in a way that is both fun and un-evil.

1D: Closer and Further Away

We’re talking about making goals and meeting them. “You know,” she writes, “back when I was going to boot camp (not real boot camp – Biggest Loser in a church parking lot at 5:30AM three times a week boot camp)…”

What?? On further inquiry it turned out that boot camp was “brutally awesome! You burn a thousand calories an hour and pray for death the entire time.”

I don’t know when the last time was I did something that courageous. But anyway:

Back when I was going to boot camp, one of the instructors said something that stuck with me. “Everything, each decision you make, moves you either closer to or farther from your goal. Nothing is neutral.” And I think we understand that for the most part – you know, that writing 500 words on your manuscript will get you closer to published, and investigating the inner recesses of your navel will not. But (social media) stuff is harder to classify. Is it productive, or just “fun”?

2D: Turning toward advantage

That is the way I usually think, but now seeing it spelled out like that, I wonder if there isn’t a downside to such one-dimensional goal-orientation? What if you have two choices, each of which (as far as you can tell) would equally contribute to the goal? If you have two goals, must action towards one necessarily be away from the other? I think a better analogy than a line (toward or away from a single goal) would be a plane (toward, away, or sideways). Then you aren’t always smacking yourself on the head for wasting your time on X when you could have done Y. You think: “having done Y, how can I turn it toward my goal”?

3D: Stumbling into something good

And then there’s potential rewards you don’t have set as goals, but stumble into accidentally. Okay. New metaphor. Imagine cost/benefit space as a rubber sheet…

…and your next novel is a majestic star

Or maybe since my background is biology, not cold and boring physics, the model of the Adaptive Landscape:

Now rather than a majestic star, imagine your next novel is a lungfish.

It’s the same idea, just flipped upside-down, where up is good and down is bad. As I stumble around in my life, I occasionally come across slopes. I know that a downward slope is probably going to lead me in a bad direction, and an upward slope might lead to rewards. But what if there’s a big peak on the other side of a little valley? What if climbing a small peak makes it harder for me to mount a bigger one? I can’t just go haring after every short-term reward that I stumble over. I have to try lots of things to get a lay of the land before I start my ascent.

4D: Warp speed!

Or, you know, I can open my eyes and look around to see how other people are managing.

Tex, with the second book of her three-book fantasy western series out today, is doing pretty damn well. What she did is less like stumbling around the adaptive landscape, and more like tunneling through it.

You’re a black hole, Tex.

She started a fantasy story way back in high school, then as she learned more about writing and the world, she changed it. Then changed it again. And followed the new path all the way into a crazy universe where the West was never won and be-wigged fish-people roam the land. You should totally go out and buy it.

March 22, 2015

92 Obsession with Ferrett Steinmetz

http://www.thekingdomsofevil.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/92Ferrett.mp3

This week I’m talking with Ferrett Steinmetz, who’s debut novel, Flex is out now from Angry Robot. Flex has been described as “Breaking Bad meets meets Jim Butcher’s The Dresden Files,” and it has a lot of themes to explore (such as body image and the limits on magic), but we’re talking about the basis of the book’s magical system: obsession.

This week I’m talking with Ferrett Steinmetz, his debut novel, Flex, and the basis of the book’s magical system: obsession.

Ferrett’s short fiction

The Nebula-nominated novella Sauerkraut Station

Dr. Strange Syndrome

When you have a big flabby magical system, I never know if the character is in danger.

If Harry Potter took magic seriously

In the real world, you can also achieve great things if you’re obsessed

Dude, what if you, like, made Felix Felicis potion, and then under its influence tried to make more?!

Get him out of the house and making bad decisions

Carrie Patel, Ferrett’s book twinsy, and what I was talking about with her

Hermione and Ron are terrible for each other! My fanfic did it better.

The internet is a glorious magnification of obsession

The Lego Gondor, Transformer costumes, and Gamergate

Nobody cares if you’re a writer, but you

Screw you, brain!

This bizarre combination of egotism and humility

Discussion questions for the comments:

How much obsession is too much and how much is too little for a writer?

How do you balance the egotism necessary to believe other people will pay for your work with the humility to improve your work when it’s bad?

How much of what we do is work at all, and how much play?

March 19, 2015

Heavy Magic Poisoning

Magic accumulates through the food-chain, from plants to herbivores to large predators, to humans. Eat enough wolf-liver and you gain the ability to make the world conform to your expectations. You become a baatar.

~~~

Kashin of the house of Ögedei watched the light shine from under the fur of the spirit-wolf and imagined the taste of its liver. Would it be as bitter, he wondered, as the liver of Güyük Khan?

March 15, 2015

The Era of Kite and Rocket

Remember Abbas ibn Firnas? Here’s what might have happened if his glider had worked.

“He flew faster than the phoenix in his flight when he dressed his body in the feathers of a vulture.”—Mu’min ibn Said

The earliest known use for the kite was suggested by ibn Firnas himself: courier. Kitings are reported from as early as the 880’s, mostly between Qurtuba itself and outlying settlements. Following the rise of Abd-ar-Rahman III and the consolidation of the Caliphate of Qurtuba, this practice became more common and ambitious, culminating in a notable (and notably unsuccessful) attempted kiting from al-Yazirat across the straits of Gibraltar in 912.

“He carried a missive to the fishes.”—An Unnamed Fisherman, quoted by Said Al-Andalusi in the Compendious History of Nations

The reasons for the use of early kites as in religion and politics rather than in the military or economic spheres should be obvious when one considers the numerous disadvantages early kite designs presented to the would-be practical kiter. Limited in altitude, range, and cargo-capacity, pre-Mongol kites could only be relied upon to deliver religious and juridical documents in short hops between one mosque and another, often along special routes lined with way towers. Most records from this time of bonfires or burning houses used to create updrafts are apocryphal.

“I am come to you bearing new orders from Allah Most High. Listen ye attentively”—attributed to Mohammad Ibn Zenati, founder of the Almustwad Caliphate

The adaptation of the kite by the Berbers for purely religious purposes should therefore be no surprise. Of course, courier-kiters and water-finders were likely as common around the Sahara then as they are today, but whatever might have been written about them was lost in revolts inspired by the “Winged Preacher” Ibn Zenati.

“Princess, there is a means of escape from this siege.” —Loyal Jafar, from the Song of Al Syd

There has been some speculation as to the role of the kite in tying together the taifa states of post-Umayyad Spain and the post-Almustwad Africa until their eventual annexation by the Karamans. Certainly, the historical record of the 12th and 13th centuries is full the kiting couriers and preachers, but it is difficult to say for certain how large a role they played in the fractured development of these small republics. Certainly the famed Owl Assassins of would have had to find some other way of swooping down on their targets.

“Beware the silent wings.” —Berber saying

Ironically, the one place air travel made a real practical distance was at sea. Sailors, usually young boys, would scale the rigging, assemble their wings, and glide the short distance to the deck of another ship. On warm days, one of these “Little Gulls” might catch an updraft and fly higher than the masthead, spying land, weather features, or ships otherwise beyond sight. Records of women Gulls, if truthful, would push back this breakthrough nearly two hundred years before their famous use by the Mongols.

“No Gulls may fly within the city walls,” —proclamation issued in the name of Erik Christoffersen, King of Denmark

“…as their excrement stains our statues.”—marginalia by anonymous clerk

It is this maritime use of kiting that spread furthest. By the 13th century, kites were in use in the harbors, if not the fortresses or cathedrals of most of Christendom as well as the Pagan port cities of West Africa and the Persian Gulf. Somewhere in the latter region, this technology finally fell into the hands of someone who could use it in war.

“The wind in our wings is the song of your doom.”—attributed to Guyuk Khan

The Mongols were great innovators. In addition to their superior cavalry tactics and archery technology, they made great use of conquered Chinese, Persian, and Arab artisans to perfect siege equipment, firearms, and of course kites. Their “Eagle Daughters,” young kited women armed with bows and launched into the air by catapult, proved devastating siege-breakers, raining burning oil, crude incendiaries, and disease-carrying offal down upon their enemies. Although stopped by the Mamelukes and their Owls in Egypt, the Eagles were likely instrumental for the conquest of Eastern Europe and Constantinople. In the end, only the Black Plague broke the Byzantine Horde, leaving the Khan of Cities cut off and vulnerable to the even more advanced Karamans with their rocket-powered “Falcon Corps.”

“Set a light to his fuse and he’ll run faster.” —Falcon drinking song

Thus, the age of sword and horse gave way to the age of gun and kite, with the shattered Christian principalities struggling to united against the Karamans as they swallowed the taifas and stretched their influence around the Meditarranean. The use of women kiters declared anathema by the Pope, Christian armies were generally weak in the air, but their navies could make use of Gulls to great effect. Although shrewd buisness practices no doubt played their role, it is likely the kite that kept the Italian states independent until the modern era.

“The wind from a burning village carried me here.”—inscription on memorial pole erected in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Certainly, it is the kite that allowed the Pomors to dominate Northern Europe and the British Isles, and let them so quickly explore the North Atlantic. Without the kites, the discovery of the Western Continents and their fabulous wealth might have been delayed for centuries. As it was, by the 16th century, Pomorian colonies in what are today Nowaziemia and Męczicia had already set the stage for the modern distribution of global power between Muslim Eastern and Christian Western Continents.

“We found gold. Send more ships.” —dispatch from Wladislaw Ierowic to king Karolinas II of Scańsko-Pomoria.

March 12, 2015

Hang-gliders

” A thousand years before the Wright brothers a Muslim poet, astronomer, musician and engineer named Abbas ibn Firnas made several attempts to construct a flying machine.” What if he had been successful?

How might functional gliders in the 9th century have changed history? That depends on what they might have been used for. Off the top of my head me got…

1. Couriers.

2. Dropping crap (boiling oil, arrows, rotting offal, grenades, actual crap) on enemies

3. Surveying (if they can sketch REALLY fast)

4. Breaking sieges. (princess, there’s only ONE WAY to get you out of here…)

5. Religious observances

6. Dueling (kick-ass!)

Any that I’ve missed?

~~~

This might be a good world-building detail to add to my No Mongols Allowed timeline.