Daniel M. Bensen's Blog, page 76

April 17, 2016

How’s English Weird?

I’m thinking about what things are hard for my students to wrap their heads around. That’s different from things in English that are hard to learn because they require a lot of rote memorization (spelling, phrasal verbs, vocabulary). What’s WEIRD in English?

Vowels: English has lots of them, but we can’t even agree on how many! Hɑhɑ! Hæhæ! Hɒhɒ! Hɔhɔ!

Also, since English got these weird vowels after spelling had standardized, a lot of words LOOK like their European counterparts on paper. It should be /biologi/, Anglophones. What the hell is /baɪɒlədʒi/?

Consonants: Not as bad, except for TH and R, which cause a lot of people trouble.

Do-support: It’s “do I know” not *Know I? or *I know (question particle)? or *I know? and “I do not know” not *I not know or *I know not) Apparently there’s something like this in Celtic languages and nowhere else? Correct me if I’m wrong.

Very little morphology: Words do change in some ways to reflect their grammatical function, but not as much as in most other languages, especially most other European languages. Often, you can’t just look at a word and tell whether it’s a noun, adjective, or verb. It’s “Buffalo Buffalo Buffalo Buffalo Buffalo” not *Buffalo-(adjective)-(plural) Buffalo-(noun)-(nominative)-(plural) Buffalo-(verb)-(plural)-(third person)-(present simple) Buffalo-(adjective)-(plural) Buffalo-(noun)-(plural)-(accusative) For this reason, some people say English “has no grammar,” which is obviously untrue. The grammatical function and relationships of words are denoted by their place in the sentence, other grammatical words (like “have”), and emphasis.

Noun animacy and countability: English has no grammatical gender, but it does divide nouns based on whether they are people and whether you can count them. “If he would just fix his mother’s shoe, they’d have a party” not *If he just fixed the shoe of his mother, they’d have party.

Tenses: There are 12 of them (although people only actually use six or seven in casual speech) Yes, there really is a difference between “I did something” and “I have done something” and “I was doing something”

Future: There are four ways to talk about the future (I will do, I’m going to do, I’m doing, I do) and they all have different (although overlapping) usages.

We don’t say yes and no: It’s true! In most languages, it’s okay to answer questions with just “yes” or “no.” In many cases in English, that would sound rude, and instead you have to repeat the subject and the modal verb of the question. Q: Is this the president? A: It is. Q: Don’t you like pasta? A: I do.

Self-consciousness: The work of evil grammarians has driven double negatives out of formal English, hopelessly muddled adverbs, scrambled subject and object pronouns, attacked the verb to BE for some reason, and given us more tenses than we ever actually use. Now I have to teach this mess! It would be so much easier if my students could just write *Nothing was never understood before she was dead,“ like they want instead of “Nothing had ever been understood about her before she died.” Does any other language punish its native speakers like that? Probably, and I’d like to hear it!

Are there other weird aspects of English that I forgot about? Or are some of the things above not actually weird at all? Did I mess up the explanations? Correct me, please!

April 14, 2016

A morning in April

I got some nice comments about the last autobiographical thing I wrote. That one was in the style of Neil Stephenson, so how about some Bruce Sterling for this one?

Note: I changed everyone’s name except mine.

“Stop!” Dan screamed.

Velly was throwing Yulie in the air. The toddler’s chubby arms and legs fell and rose, lagging behind her center of mass as she reached the apex of her arc and came back down again.

“Velly, stop!”

Velly didn’t listen. Velly never listened when her father told her to stop. Or really anyone. Stopping was not something Velly did well. She caught Yulie, then heaved her little sister back into the air with all her 3-year-old strength.

This time Velly didn’t catch Yulie. Yulie hit the ground toe-first, and Dan could see the toe, the leg, the shock of impact travelling upward in a sine wave. Where that wave crossed the axis of the bone, that bone cracked. A perfect mathematical model of catastrophe.

Dan woke up. He was lying on his side in his daughter’s bed, with Velly’s sweaty face pressed into his shoulder. Had she peed on him again? No, that was just more sweat.

Dan breathed, reminding himself that Velly was too small to throw Yulie. That Yulie was sleeping with her mom. There were no broken bones, no babbling orthopedic surgeons, no trips to that awful, nurse-haunted hospital.

Velly was sleeping at Dan’s back under a down comforter and wearing pajama pants, which meant he couldn’t see the T-shaped scars over her hips. But he knew they were there. Those scars would always be there. They’d probably impress the hell out of some boy, some day.

“Daddy,” said Velly.

Shit. She was awake. Dan had been hoping to surf Tumblr on his phone until she woke up. He was sure the bizarre and socially conscious images of Tumblr would sear the breaking tibias right out of his head. Maybe she’d just been talking in her sleep. Maybe if she was awake, she would go back to sleep.

“Daddy. It’s morning time.” Velly had not been talking in her sleep. Velly was awake and ready to tackle and subdue another day. “Is it Easter yet?”

“No, lovey. Easter is in two weeks.”

“Do I have to go to Day Care today?”

Dan rolled over under the comforter to address his daughter. “Yes. Today is Tuesday. You get to go swimming. Do you want to go swimming?” Velly loved swimming. It had been an important part of her physical therapy between surgeries. “Did you have good dreams?”

Velly peered at him from a thicket of sticky, dark blond ringlets, eyes wide and hazel. “Where’s my milk, daddy? I’m waiting for my milk.”

“‘Please get me some milk, daddy,'” Dan modeled.

“Please get me some milk, daddy! I love you!” Her dimples would swallow a man whole.

Velly had learned to speak scarily early. Dan and Pavlina had assumed that was because her surgeries had rendered her immobile from months 3 to 9 and 15 to 19. According to this theory, Velly had focused on hand-eye coordination and speech because she had no motor skills to develop below the waist. Except now, her 8-month-old little sister was beginning to babble in a disturbingly comprehensible way.

“Mama! Mamamam! Mmmm!”

Dan slid out of the bed he shared with his older daughter and stumbled into the room his wife shared with his younger daughter. There he found Yulie crouched upon her mother, surveying her domain. At the creak of the door, her toddler head came around, huge and bald and terrible.

“Dada!” Yulie smiled at Dan, eyes and mouth like an emoji in the harsh morning sunlight. “Dadada! Babbbp!” She trundled down the slope of her mother, speaking the syllables she would soon hone into a tool of mastery of those around her, just like her sister.

“Daddy!” Called Velly from the other room. “I told you to get me some milk.”

“I have to take care of Yulie, Velly.” Dan caught the toddler up in his arms before she could crawl off the bed. This girl approached the world like a human cannon-ball. She was sure that if she fell, she’d break the ground.

Dan pressed his cheek against Yulie’s and inhaled. His baby smelled like poop.

“Switch babies,” said Pavlina from the bed. “I’ll gush Velly.”

“How did you sleep?” asked Dan.

“We woke up at four again,” said Pavlina. “We played. We bit our mommy. How about you?”

“Velly was fine,” said Dan. “I had nightmares.”

“Daddy, tell me about the taxidermy animals.” It was Velly in the doorway, interrupting with as much care as a channel-surfer.

“I’ll tell you about taxidermy animals later.” Man, but it had been a bad idea to tell Velly where the animals in the natural history museum had come from.

Velly turned away from her father. He was dead to her. “Mamo, iskam mleko!”

“Dobre, mame,” mumbled Pavlina, shuffling past Dan. “Idvam.”

What Velly called “milk” in English and “mleko” in Bulgarian was actually ayran, a cold drink of yogurt mixed with water and, traditionally, salt. Pre-children, Pavlina had amazed and entranced the staff at Indian restaurants in the US by ordering and consuming with gusto their salt lassis. Now she dragged herself into the kitchen to mix yogurt and water in a bottle for their daughter, who was addicted to the stuff.

Yulie’s fists went to Dan’s throat, fumbled there for his iPod shuffle. Her expression was intense, concentrated as a chess grand master. She had no greater desire on Earth than to cram that piece of electronics into her mouth and crunch down on it with both teeth.

The coffee pot popped. Had Dan turned it on and brewed their coffee? Had Pavlina? Had they left it on since last night? If the last, could he juggle Yulie and make coffee without spilling everything everywhere?

Yulie reached up and gave Dan’s face a hard slap. She was not interested in coffee. Dan was, though. Dan’s interest in coffee went beyond the chemical, beyond even the physiological. Dan’s need for coffee was spiritual. It was transcendental. It was Cartesian. Consciousness was impossible without coffee, only a series of muscular contractions ingrained by grueling hours of conditioning.

Dan wrestled Yulie to the side. She wrestled him back. He managed to get a glimpse of the watch he didn’t remember putting on. It was 7:30. They had half an hour to get out the door.

April 10, 2016

Deliver what you promise

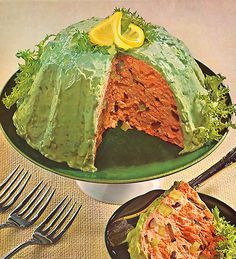

Here’s a disgusting analogy from Tex Thompson: don’t serve people lime jello with meat inside. It’s not that meat jello is necessarily bad, but it’s something you have to prepare people for in advance. You can’t trick people into eating it.

“But,” a younger me said, globules of idiocy coagulating on the surface of my dunce-cap, “won’t people be intrigued when they think they’re getting boring old conventional jello and then I subvert the trope and give them aspic? Wouldn’t that be clever of me?”

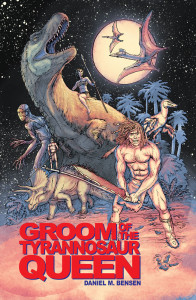

No, moron. When you write a Conan-esque book that characterizes the big, strong warrior as a trauma-riddled sociopath who needs a good woman to help him get in touch with his emotions, you alienate people. People who like Conan will get mad that you poked holes in their favorite character, and people who like romance and psychological drama won’t pick up a Conan book in the first place. Nobody will buy the damn book. (uh, available now on Amazon!)

And yet I did it again. Hey folks, do you like Captain Kirk-type characters who have sex with hot aliens? I wrote a book like that, except the aliens are tentacle monsters and giant spiny worms! What about a swash-buckling James Bond-type agent of the Ottoman Empire…who is cursed to be unable to hurt anyone? An animal-loving naturalist protecting space-dragons…by putting all of humanity at risk?

The thing is, I like aspic. I like books that turn out to be deeper and more complex than their space opera or epic fantasy or horror exterior. I bet you do too. The problem is that you have to trust the person handing out the aspic. Bujold, Pratchett, and Gregory all of them started their writing careers with more conventional books. They also never forgot to actually include the thing they promised in each book. There actually are spaceships fighting in the Vorkosigan Saga, knights battling dragons in Discworld, and scary, awful things happening to unsuspecting people in Daryl Gregory’s books.

That’s why Junction, although it deals with murder, love, and the dark depths of tribalism, is mostly about alien monsters eating people. Fingers crossed on this one.

So what books do you like because they subverted tropes and gave you something different than you expected? What books did you hate for the same reason? What was the difference?

April 7, 2016

If the Ice Age never ended

What if it were the Last Glacial Maximum lasted another 26 thousand years? The world would be a colder place, yes, but more importantly it would be a more climatically extreme place. Travelling north and west through an Arabian desert about as dry and hot as in our timeline, you’d pass through savanna in Anatolia, a bit of forest steppe, and then BAM, you’re on the tundra.

It could be that civilization in Mesopotamia and India might develop along recognizable lines in this world, but Phonetician and Egyptian explorers would have found nothing north of their north-Mediterranean outposts but frozen wastes populated by increasingly monstrous denizens.

April 5, 2016

Pearson is Dead

I wanted to show you what I am working on in Junction right now. On this second revision, I’m trying to go back to some key scenes and add romance and mystery elements. The same basic things are happening, but the characters (especially the main character, Daisuke) react to them in a deeper, more engaging way.

Also, spoilers I guess? Although it’s not much of a spoiler in an alien-survival-murder-mystery when someone gets murdered and there are aliens involved.

Here’s the scene in the beta-version of the story:

“Commander Pearson is dead?” Hariyadi nearly shoved Daisuke off the hill as he whirled to face Misha. “How did this happen?” His eyes narrowed. “How was it allowed to happen?”

Misha only shrugged. With his sagging shoulders and thriving facial hair, the man looked like a depressed bear, emerging from its hibernation only to find its favorite salmon stream had been paved over. “I do not know how he died. Are no marks on body. No evidence of new trauma or allergy. Simply: he is not breathing.”

Hariyadi strode past Misha and stuck his head into Pearson’s tent. Daisuke could hear him muttering. “No allergy. No evidence of foul play. Observe the extensive damage to the legs…shock, perhaps, or some slow-acting poison.”

“As if bioactive molecules from aliens would have anything like the intended effect on us.” Blond curls flew as Anne shook her head. “Wait a second? What is Hariyadi doing?”

“Capturing the moment.” Daisuke tapped his life logger. “Speaking for the benefit of our audience.”

Anne’s expression twisted, as if in disgust that anyone could be so gauche as to think of filming a moment like this.

“What’s going on?” Nurul mumbled, climbing out of the women’s tent. She shivered under her thermal blanket, glaring blearily at the rest of the party, as if looking for the person who had turned down the thermostat.

“Pearson is dead,” said Anne.

“Oh!” Nurul’s blanket fell to the ground as she put her hands to her mouth, revealing clothes stained and in some cases eaten right through by Glasslands effluvia. “That’s terrible! Was it his wounds that killed him?”

Anne let out an exhausted sigh. “I suppose it must have been. It’s not like we can do an autopsy on him out here. Or a decent burial.” She ran her hands through her hair, turning it into a rather fetching nest-shape.

“No,” said Hariyadi. “We can’t bury him. We don’t have time.”

Anne rounded on him. “I think we do have time. Would you like us to leave your corpse out here when you die?”

Hariyadi raised an eyebrow. “When I die?”

“When all of us die, she means,” said Misha.

Anne just looked bleakly down at the ground.

And that’s when I knew I had to intervene. Daisuke found himself stepping forward and clearing his throat, checking to see where Rahman and his camera might be.

“We will bury Commander Pearson’s body,” he said.

He looked around. “Misha? Get the shovels.”

“Okay,” said Anne, while the Russian sloped off to the sledge, “but then what?”

“We will all dig together,” said Daisuke. “Just as all together we will help each other to survive. We will not give up.”

“Okay?” she said. “But I meant ‘what about decomposition?’ The bacteria in his gut will go some way to breaking his body down, but they won’t thrive down there in the quicksand. Local bacteria and scavengers can’t digest him. His nutrients will be wasted. Inaccessible.”

Daisuke prevented himself from asking “so what?” If anything, the sixty kilos of biomaterial donated by Pearson would help terraform this place.

Daisuke took a moment to compose the thought into a media-friendly form and said, “Perhaps his body will form the basis of an earthlike ecosystem. Future explorers might find here an apple tree growing in the oasis made by Pearson’s sacrifice.”

Anne just snorted.

The tree image would slot right into an American’s Johnny Appleseed mythology. Maybe Daisuke should have said something about billabongs?

“We cannot bring him with us,” said Hariyadi, who took a shovel readily enough when Misha handed it to him. “I am unsure how much longer we can even continue to use the sledge.”

That was a problem Daisuke had been considering, too. They had more supplies than could be carried in backpacks, but the ground was becoming less and less even as they got closer to the mountains. Wheels would help, but would they be enough?

But if Daisuke voiced his idea now, it would be swamped by the crew’s reaction to the death of Pearson. He had better sit on his plans until after the grieving scene.

“We’ll think of something.” Daisuke put a hand on Anne’s shoulder, showing support. Where the hell was Rahman with that camera? “For now, we dig.”

. It was far more difficult to carry Pearson’s body down the slippery incline of the hill than it was to lever up the tiles down there. The chalky sand below was entirely dry.

“What do you think happened, Anne?” asked Daisuke. “Where did the water go?”

She didn’t answer, only stared into the grave as if imagining it filled with the decomposed slime.

Daisuke breathed deeply, trying to crush this sudden annoyance at Anne. But why was she indulging in so much grief? There were tears on her face, but she’d never liked Pearson! She’d barely been able to exchange a civil word with him. Did Anne imagine she could wedge herself into the middle of the old swordmaster/naive protégé dynamic Daisuke had been building? Or had Anne been establishing her own relationship drama? Perhaps a romantic antagonism with the old man…

Stop.

Daisuke realized with a twist of self-loathing that he was thinking like a TV personality.

Pearson thought I was a flunky, eager to wipe away my ancestors’ wrongdoing by serving Uncle Sam. I had no problem using those assumptions to construct my own narrative about teaching the arrogant American to respect my survival skills.

Now both those stories were dead, and the only real emotion Daisuke could summon was pique that Anne and Pearson’s story was more interesting than his.

You’re pitiable, Daisuke, he thought in the voice of his ex-wife, like an egg-shell with nothing inside. This is a funeral, and you can’t even summon up the humanity to be sad?

Apparently not, but if Daisuke couldn’t be a real human being, he could sure as hell act like it. He rubbed his ring finger and composed his expression into heavy grief.

Hariyadi and Rahman lowered Pearson’s body into its grave. Scooped their shovelfuls of sand onto it. Everyone took their turns at the ritual, even Tyaney and Sing. What were their death rituals like, Daisuke wondered. How did they grieve?

Hariyadi must have been wondering something similar. “Ms. Houlihan,” he murmured once the corpse was buried, “do you have anything you would like to say?”

Anne shook her head. “What? I’m not…I don’t know any prayers.” She looked like she’d been hit very hard on the back of the head. “He was just alive last night. Joking. Or whatever the hell that story was supposed to be.”

Daisuke couldn’t help smiling at her. Of course Anne hadn’t been romantically interested in Pearson. That suspicion was just Daisuke being…jealous? Huh.

“So you are an atheist and will not say a prayer for the commander,” said Hariyadi. “Mr. Alekseyev? Do you share a God with the deceased?”

“Churches are beautiful buildings,” said Misha.

Daisuke might be able to make Anne feel better. That might go some of the way to lifting this weight out of the pit of his stomach.

“I’ll say a few words.” Daisuke looked at Anne. Not at Nurul, who was gesturing hurriedly at her husband to get his camera. Daisuke did not know whether to feel elated or depressed, proud of or disgusted with himself. With the ease of much practice, he buried those feelings and placed over them the glassy tiles of professionalism.

And here’s the gamma-version:

“Commander Pearson is dead?” Hariyadi nearly shoved Daisuke off the hill as he whirled to face Misha. “How did this happen?”

Misha only shrugged. With his sagging shoulders and thriving facial hair, the man looked like a depressed bear, emerging from its hibernation only to find its favorite salmon stream had been paved over. “I don’t know how he died. No marks on body. Simply: he is not breathing.” He looked at Daisuke. “You gonna help me?”

“Help?” Daisuke echoed.

“Help move body. Hard to bury him up here.”

Daisuke blinked. Well, of course, they had to bury Pearson. They couldn’t very well drag the corpse with them over the mountains. A corpse. One of their number had died.

“No,” said Hariyadi. “We can’t bury him. We don’t have time.”

Anne rounded on him. “Would you like us to leave your corpse out here when you die?”

Hariyadi raised an eyebrow. “When I die?”

“When all of us die, she means,” said Misha.

Anne just looked bleakly down at the ground.

And that’s when I knew I had to intervene. Daisuke found himself stepping forward and clearing his throat, checking to see where Rahman and his camera might be.

“We will bury Commander Pearson’s body,” he said. “Misha? Get the shovels.”

“Okay,” said Anne, while the Russian sloped off to the sledge, “but then what?”

“We will all dig together,” said Daisuke. “Just as all together we will help each other to survive. We will not give up.”

“Okay?” Anne said. “But I meant ‘what about decomposition?’ The bacteria in his gut will go some way to breaking his body down, but they won’t thrive down there in the quicksand. Local bacteria and scavengers can’t digest him. His nutrients will be wasted. Inaccessible.”

Daisuke prevented himself from asking “so what?” If anything, the sixty kilos of biomaterial donated by Pearson would help terraform this place. But the habit of long training took over and what Daisuke ended up saying was. “Perhaps his body will form the basis of an earthlike ecosystem. Future explorers might find here an apple tree growing in the oasis made by Pearson’s sacrifice.”

Anne just sniffed. Was she fighting back tears? Why? She’d never liked Pearson. She’d barely been able to exchange a civil word with him. Daisuke might be excepted to shed a many tear for the fall of a gruff old mentor, but what sort of relationship drama had Anne established? Romantic antagonism?

Daisuke realized with a twist of self-loathing that he was thinking like a TV personality.

You’re pitiable, Daisuke, he thought in the voice of his ex-wife, like an egg-shell with nothing inside. This is a funeral, and you can’t even summon up the humanity to be sad?

Apparently not, but if Daisuke couldn’t be a real human being, he could sure as hell act like it. He rubbed his ring finger and composed his expression into heavy grief. “Let’s get the body.”

Pearson’s body itself showed no signs of struggle. The corpse lay on its back under a silvery thermal blanket, its arms limp at its sides, its skin waxy and bejeweled with dew. Its mouth and eyes were closed. The man looked more peaceful than he ever had when alive. Daisuke muttered a prayer to Amida Buddha as he squatted at the corpse’s head and slid his arms under its armpits.

“So what happened?” asked Hariyadi as Misha and Daisuke waddled past with their grizzly cargo. “Allergy? Shock? Poison?” His eyes scanned across Daisuke’s face, Misha’s, Anne’s, narrow with suspicion.

“Well, we can rule out poison,” said Anne. “The shmoo injected him with something, but I doubt bioactive molecules from aliens would have anything like the intended effect on humans.”

“Allergies?” pressed Hariyadi.

Anne made a considering noise. “I wouldn’t be surprised if it wasn’t even the Shmoo that killed him, just his own immune response to the alien germs that took up residence in the wounds post-facto.”

“What’s going on?” Nurul mumbled, climbing out of the women’s tent. She shivered under her thermal blanket, glaring blearily at the rest of the party as if looking for the person who had turned down the thermostat. Then her eyes fell on Daisuke and Misha. Pearson’s body. She stiffened, her face setting like cement.

“Pearson is dead,” said Anne.

“Oh!” Nurul’s blanket fell to the ground as she put her hands to her mouth, revealing clothes stained, and in some cases eaten right through, by Glasslands effluvia. Her forehead furrowed with shock and distress. “That’s—how terrible! Was it his wounds that killed him?”

Anne let out an exhausted sigh. “I suppose it must have been. It’s not like we can do an autopsy on him out here. Or a decent burial.” She ran her hands through her hair, turning it into a rather fetching nest-shape.

“Yes,” said Misha. “We bury him. If we don’t die of exhaustion carrying body downhill. Come on, Daisuke.”

It turned out that carrying Pearson’s body down the hill had been the most difficult part of the burial process. With only a little pressure from the edge of a shovel, the tiles that made up the ground of the Glasslands popped out of their sockets. The chalky sand below was entirely dry and easy to shift.

Small creatures like hard candies made of glass tinkled out over the ground as their shovels emptied out a grave. What would such creatures make of the body of a human? Would it poison them? Would they die of an immune reaction like Anne and Nurul almost had? Like Pearson? Daisuke grimaced at the thought. He’d experienced the early symptoms, himself. He’d experienced the early stages of anaphylaxis, himself.

Daisuke remembered burning pain, swelling of the eyes nose and throat. Anne clawing at her own skin, her rictus grin of pain and terror.

Pearson’s body, however, was as peaceful as a Buddha.

The plane crash might have been accidental. So might the animal attack. So might the deadly poisoning. Perhaps Junction was just that dangerous a place — more dangerous than the worst bush Daisuke had ever trekked through.

Or maybe, gentle audience, it is not Junction that is dangerous, but the human soul.

Tales from the Universe reviews

And now for a bit of personal horn-tooting. Reviews are coming in for Tales From the Universe, and the general impressions of my story (“The Devout Atheist”) are good! Ish!

“ I feel the publisher/editors are taking a chance with their story order, as the first one dabbles with religion and this may be a bit off-putting to start the book. Not a knock on the talent…but it did cause me to force myself to continue. “

I was fascinated by Daniel Benson’s ‘The Devout Atheist’, with its interesting take on a Biblical, speculative Universe. I’ll say no more.

The first story is going to throw you off. It threw me off. It isn’t a typical science fiction, but it definitely makes you think. Once you get past the fact that science is a religion and religion is fact, the story definitely made me pause and wonder. It poses some questions that aren’t addressed too often.

a stunning reverse take on religion vs atheism

I’m gonna call this a “yay”

April 3, 2016

Demonstrate, don’t explain

By CorvinZahn – Gallery of Space Time Travel (self-made, panorama of the dunes: Philippe E. Hurbain), CC BY-SA 2.5

You know how people say “show, don’t tell” and when you’re a dewey-eyed newberry dough-writer you take that advice way too seriously and write a 5 billion word novel? And then you get disgusted with showing and your next novel is only 5 words long? Yeah? That’s happened to you?

Well here’s a different spin on the rule that would have saved me a lot of trouble if I’d known it before: demonstrate, don’t explain.

Sometimes you have to tell. Sometimes, you shouldn’t show. But when you’re writing speculative fiction and you’re talking about the central conceit of the whole story, you can’t just explain it. You have to have your characters demonstrate how it works.

Junction is a good example of the good things that happen when you apply this rule and the bad things that happen when you don’t. In Junction, a wormhole at the bottom of a pit in the New Guinea Highlands connects to a wormhole at the top of a mound on an alien planet. That’s it. I just explained it.

I used basically the same words in the manuscript. I used them over and over again, in several different places, both as internal and external dialogue. And a whole bunch of beta-readers were STILL confused. “What is that thing at the bottom of the pit?” they would ask, “where is the wormhole?” “why was it in a pit a moment ago and now its on a mound?” “What planet are we on?”

These weren’t stupid questions. I have the same problem reading other people’s work because (guess what) explanations are boring and my eyes just glaze over them. It doesn’t matter if the author repeats the explanation. That just makes it more boring. Even when I do register the explanation, my own presuppositions get in the way. “No,” I say, “wormholes don’t work like that. That character explaining them must be wrong.”

On the other hand, something nobody had any trouble with in Junction was alien biology. When the semipermeable-bag-within-a-silicone-bag-within-a-layer-of-hydrochloric-acid-within-a-second-silicone-bag-pierced-by-silicious-spicules showed up, nobody had any problem with it. That’s because I first had my heroes look out at a landscape covered in glass, then see a little rolling animal that’s build a glass shell around itself, then a larger animal that has broken the shell up into glass spines embedded in a tough layer of silicone, then the big animal, whose first action is to attack another animal and eat it. My readers knew exactly what that thing was (a bag of acid covered in glass shards) and what it was going to do (try to eat them). Bam.

That’s demonstrating. That’s making people believe you. So I’m going to go back and demonstrate the hell out of those wormholes.

March 31, 2016

Space Janissaries

Back last spring, I was deep in research for Charming Lies and thinking about Interstellar Empires and space opera. Blah blah blah…what if OTTOMAN EMPIRE IN SPACE?

The way I’m thinking is this: things get weird in human space with the invention of nanotechnology and the end of scarcity. What do you do with the ability to conjure objects out of gray goo? How do you control people any more?

The first answer is that you don’t. Everyone can talk to the goo and make their own artifacts. This is an ideology suited to individuals or small groups of people roaming the solar system. These people, the Free, have developed some nifty techniques for wielding nanotechnology, but they’ve tended to fair badly against larger, more organized groups like…

The Select, who only allow people access to nanotechnology after they’ve passed through a long and arduous process of education. Of course there are many splinter groups who started their own accreditation programs, some more respected than others. They’ve made some important innovations in nanotechnology, and control about half of the solar system. The better half, however, is controlled by…

The Exalted, who have wedded nanotechnology to implanted interfaces, training children from infancy. While their movement began as an effort to bring all citizens access to nanotechnology like the Free, the Exalted government awards people weaker or more powerful interface devices depending on how much people are willing to pay. Their hereditary oligarchy controls the interface hardware, and ensures it keeps the best toys for itself.

You can recognize these three ideologies by the form of nanotechnology they use: the Free carry around sacks of gray goo, the Select surround themselves in clouds of utility fog, and the Exalted are swathed in intelligent cloth.

The Exalted were once the premier power in the solar system, but since the Select discovery of an extra-solar brown dwarf and its associated, resource-rich moons, Exalted dominance has waned. Worse, the old oligarchs have given too much leeway to their soldiers, whose demands for better interface chips have given them the power and the skills to overthrow their masters…

So go back and look at that picture above. Can you spot the space-Janissary? What else do you think might be going on in the space-Renaissance?

March 28, 2016

Stations of Life

Out of humanitarian and profit-motivated interests, governments in the 22nd century have built a trans-time rail system to connect and alter the past. There are the stations they have so far established.

1. Raj Station est. 1907 (0 years ago) Preventing: WWI, Knickerbocker Crisis, Spanish Flu Epidemic. Generation: Victorians Problem: Aristocracy Aesthetic: Steampunk

2. Roaring Station est. 1929 (6 years ago) Preventing: The Depression, WWII. Generation: Flappers Problem: Demagogues Aesthetic: Diesel -punk

3. Great Leap Station est. 1958 (10 years go) Preventing: Great Leap Forward, Partition of India, Cold War. Generation: Greats Problem: Elected officials Aesthetic: Atompunk

4. Iron Station est. 1987 (15 years ago) Preventing: Black Monday, early 90s Global Recession, post-Soviet Kleptocracy, Financial Crisis, Proclamation of Caliphate. Generation: Boomers Problem: Terrorists Aesthetic: Cyberpunk

5. Singularity Station est. 2021 (18 years ago) Preventing: Refugee Crisis, Last Crash, The Pivot, World War III, Water Crisis. Generation: Millennials Problem: Appointed officials Aesthetic: Podpunk

March 24, 2016

PERILOUS PAULINE: ROMANCING THE STONE AGE

You may not be aware of this, but the hilarious Tex Thompson has an even more hilarious alter-ego named Perilous Pauline, a rootin-tootin agony aunt who delivers folksy sarcasm to fictional characters. I (in the voice of Andrea, the main character of Tyrannosaur Queen) sent Pauline a call for help, and this is how she responded:

Okay. Here’s the thing. I’m a soldier from the mid-twenty-first century. Yes, I know that means I’m out of a job. No, I don’t want to talk about it. What’s important is that my current job, body-guarding scientists on trips back in time, has taken a turn for the fucked up.

Wait, wait. Let’s review. You’ve been sent back in time, taken prisoner and forcibly married to a homicidal Neanderthal, and your biggest problem is that he’s gay?