Jennifer Petkus's Blog, page 2

October 4, 2013

Playing the Austen version of the Great Game; observations on the AGM

After clicking the photo, open the image in a new window to view full resolution, 4,418 x 1,080 pixels

Sherlockians understand the Great Game as being the conceit that the fifty-six short stories and four novels that comprise the Canon were written by Sherlock Holmes’ biographer, Dr. John H. Watson, and that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was merely Watson’s literary agent. These stories, written over four decades and spanning the reign of three monarchs, were often written quickly to supplement Watson’s income as a doctor, and thus they are filled with inaccuracies and are inconsistent.

And yet Sherlockians do their best to reconcile these inconsistencies, searching railway timetables, consulting maps and demographic data to justify a location, a person, a tide or even the weather. Scholars have posited improbable gymnastics so that Watson might have been injured in both the shoulder and the leg at the Battle of Maiwand, rather than accept the fact that the real creator of Holmes and Watson never gave his most famous creations the attention to detail that he lavished on his historical novels.

When I became a Janeite, I thought Austen would be mostly free of this sort of conceit, but at the recent Jane Austen Society of North America Annual General Meeting in Minneapolis, I realized the Great Game exists in other fashion. The most obvious example is the search for Pemberley, the home of Fitzwilliam Darcy in Pride and Prejudice. Dr. Janine Barchas gave one of the plenary presentations—Naming Names in Pride and Prejudice—where she discussed the Fitzwilliam name and its connotations during Austen’s time, and also Wentworth Woodhouse (in South Yorkshire), the home of the Earls Fitzwilliam. She broadly suggested Wentworth Woodhouse as a model for Pemberley. It seems a natural choice, especially as the name suggests characters from Emma and Persuasion.

When I became a Janeite, I thought Austen would be mostly free of this sort of conceit, but at the recent Jane Austen Society of North America Annual General Meeting in Minneapolis, I realized the Great Game exists in other fashion. The most obvious example is the search for Pemberley, the home of Fitzwilliam Darcy in Pride and Prejudice. Dr. Janine Barchas gave one of the plenary presentations—Naming Names in Pride and Prejudice—where she discussed the Fitzwilliam name and its connotations during Austen’s time, and also Wentworth Woodhouse (in South Yorkshire), the home of the Earls Fitzwilliam. She broadly suggested Wentworth Woodhouse as a model for Pemberley. It seems a natural choice, especially as the name suggests characters from Emma and Persuasion.

There have been many candidates for Pemberley, of course. The website for Chatsworth House doesn’t quite come out and say it is the model for Pemberley, but it makes no bones about it being used for the filming of Death Comes to Pemberley, the BBC adaptation of P.D. James’ novel. My UK Janeite friend Christopher Sandrawich has some sympathy for the nomination of Chatsworth House, based primarily on the topography and the aspects of the land to be had from various projections of the house, although he admits Chatsworth House would be too grand for Darcy’s “ten thousand a year.”

Concerning the nomination of Wentworth Woodhouse, he responded:

It isn’t in Derbyshire; it is in Yorkshire

It is a handsome stone building but

It does not stand on rising ground

No high wooded hills at the rear

No stream in front, not artificially widened

No bridge to cross, and

Cannot be viewed from the other side of a valley by a carriage reaching a clearing in the woods, which then descends to the bridge

I have no idea if it has a Park 10 miles around, but you certainly cannot in the front of the house walk alongside a stream and talk of fishing

The stables appear to be around the back and are not sited as with Chatsworth so that their owner could appear around the corner of the building to surprise visitors on his lawns.

To him, these are all very damning arguments, but I have to laugh, both because I admire his reasoning and because it all seems rather silly. I think it reasonable that Austen had any number of grand houses in mind when she created Pemberley, from Stoneleigh Abbey to Chawton House to Godmersham Park to Chatsworth House.

Something else that was wonderfully silly was Tim Bullamore’s breakout session, Wickham Wanderer: Was Lydia Bennet’s Lover Mad, Bad or Simply Misunderstood? Bullamore, editor and publisher of Jane Austen’s Regency World, went through verbal gymnastics to cast poor Wickham as simply the plaything of the scheming Georgiana Darcy. And Diane Capitani and Holly Field found a surprising depth in A New View of Mr. Collins or: “You Used HIM Abominably Ill.” They argued that our poor opinion of Mr Collins comes from Lizzie Bennet and question her reliability.

I think we have the freedom to play the game with Austen’s stories in this fashion because of her use of free indirect discourse. If you’re unaware of the term (which I was before I became a Janeite), it refers to her third-person narrative style that occasionally takes the viewpoint of one of the main characters. I had several conversations with other attendees about the difficulty of really knowing what’s going on in Austen’s novels—whether one can always believe the narrator.

I also attended a talk by Jocelyn Harris, Introducing Elizabeth Bennet, who made a compelling argument, backed by no concrete evidence, that Austen may have modeled her most famous heroine after the actress Dorothea Jordan, mistress of the Duke of Clarence (later William IV). And, of course, she mentioned the exhibition of the paintings of Sir Joshua Reynolds at the British Institution in 1813, an exhibit that has been recreated online by Janine Barchas, mentioned earlier. It’s a curiously circular world of Austen scholarship, that becomes increasingly self-referential. It’s almost as if one could create a Unified Field Theory of Austen, a gigantic flowchart that always leads back to certain touchstones and the one ring of power (to borrow from Tolkien), on which is inscribed, “It is a truth universally acknowledged …”

I also attended a talk by Jocelyn Harris, Introducing Elizabeth Bennet, who made a compelling argument, backed by no concrete evidence, that Austen may have modeled her most famous heroine after the actress Dorothea Jordan, mistress of the Duke of Clarence (later William IV). And, of course, she mentioned the exhibition of the paintings of Sir Joshua Reynolds at the British Institution in 1813, an exhibit that has been recreated online by Janine Barchas, mentioned earlier. It’s a curiously circular world of Austen scholarship, that becomes increasingly self-referential. It’s almost as if one could create a Unified Field Theory of Austen, a gigantic flowchart that always leads back to certain touchstones and the one ring of power (to borrow from Tolkien), on which is inscribed, “It is a truth universally acknowledged …”

Of course the current Austen ring (now you see why I invoked Tolkien) is the one briefly owned but never possessed by pop star Kelly Clarkson. It was mentioned by many at the AGM and I made the unfortunate remark that I didn’t see what the fuss was. I’m afraid I care little for jewelry. To me, Austen lives in her novels and surviving letters, and the propriety of her ring leaving England is problematic for the country that maintains dubious claim to the Elgin Marbles. But to many, the few objects Austen owned provide fixed points in time and space that help understand her relationship to her world and those references to it we find in her novels.

That pre-occupation with Jane’s relationship with her world sometimes makes me despair for poor Jane. I imagine her sitting down to write with a checklist: must place Barton Cottage in Devonshire because of generous poor laws; work in reference to venereal disease (“Kitty a fair but frozen maid?”); have I mentioned the picturesque lately? So many scholarly investigations of the underpinnings of Jane’s novels give an image of an intensely calculating author. Instead, I like to think Jane wrote as I wrote. She walked and thought and returned to her desk to let the ideas flow. I realize, of course, that these scholars don’t really suggest Jane was calculating—they admit she was merely a product of her times—but an over analysis of her life and times has the effect of making her seem overburdened with agenda.

That’s probably why I enjoyed Dr. Joan Ray’s plenary talk, Do Elizabeth and Darcy Really Improve “upon acquaintance?” Dr. Ray, former JASNA president, showed the extent that Darcy’s slight—“She is tolerable, but not handsome enough to tempt me”—rankled Elizabeth throughout the book. We think of Elizabeth as a exemplar of womanhood—independent, proud, intelligent—but Dr. Ray, simply by counting the days from that first informal dance at Lucas Lodge to the Netherfield Ball, shows how long Elizabeth carried a grudge. Get over it. And Dr. Ray also showed how quickly Darcy re-evaluated Elizabeth and how much Elizabeth’s pride prevented her from seeing him anew.

In fact, several presenters mentioned that many first-time readers of Pride and Prejudice, especially those not prejudiced by seeing the many adaptations, find Elizabeth a bitter pill. Her dismissal of Charlotte Lucas’ decision to marry Mr. Collins being a case in point. I enjoyed Dr. Ray’s talk because it dispensed with needing to consider English politics, Austen’s antecedents or the influence of Radcliffe, Scott or Richardson (authors Austen admired). Instead it focused on the very understandable motivations of a young woman who’d been slighted by a handsome man; no need to play the great game at all.

Of course, I’m guilty of playing the game myself where Austen is concerned. I have twisted facts to fit theories—something Holmes warned against. For the purposes of my book, Jane, Actually, I thought it more poignant that the only portrait of Austen be the watercolor/pencil sketch created by Austen’s sisten, Cassandra. Recently, of course, there’s been news about the Rice portrait, painted by Ozias Humphrey, that some maintain depicts a young Jane Austen. Claudia Johnson, a noted Austen scholar, champions this view. The National Portrait Gallery in London has so far refused to weigh in on the controversy; they earlier declined to purchase the Rice portrait.

Of course, I’m guilty of playing the game myself where Austen is concerned. I have twisted facts to fit theories—something Holmes warned against. For the purposes of my book, Jane, Actually, I thought it more poignant that the only portrait of Austen be the watercolor/pencil sketch created by Austen’s sisten, Cassandra. Recently, of course, there’s been news about the Rice portrait, painted by Ozias Humphrey, that some maintain depicts a young Jane Austen. Claudia Johnson, a noted Austen scholar, champions this view. The National Portrait Gallery in London has so far refused to weigh in on the controversy; they earlier declined to purchase the Rice portrait.

I remain skeptical, but I admit I remain so because it suits my purpose. This large, beautiful painting of a young girl would make such a lovely representation of Jane, but even if it were universally acclaimed, I still think I would prefer the sour puss image I put on the button I distributed at the AGM.

I remain skeptical, but I admit I remain so because it suits my purpose. This large, beautiful painting of a young girl would make such a lovely representation of Jane, but even if it were universally acclaimed, I still think I would prefer the sour puss image I put on the button I distributed at the AGM.

So after four days of hearing Austen dissected and watching Janeites wearing muslin and secreting their iPhones in their reticules, I’m happy to return home and simply enjoy Austen as a simple entertainment. Probably my nicest memento of the AGM was the parting gift given to us by the Minnesota region: a simple copy of Pride and Prejudice. It’s not my crushing annotated copy or a beautifully illustrated one. It’s small enough to put in my purse or take on a bike ride. It’s pretty guileless; no need to play games at all.

September 21, 2013

Jane, Actually is #Free for the #Kindle Sept. 20-22

Jane, Actually or Jane Austen’s Book Tour is now a Kindle Select. Any Amazon Prime member can read it for free and from Sept. 20 to the 22nd, anyone can download it for free from Amazon. In the United States; in the U.K.; in Canada. It’s also free in India, Spain, Italy, Germany, France, Brazil, Mexico and Japan.

Jane, Actually or Jane Austen’s Book Tour is now a Kindle Select. Any Amazon Prime member can read it for free and from Sept. 20 to the 22nd, anyone can download it for free from Amazon. In the United States; in the U.K.; in Canada. It’s also free in India, Spain, Italy, Germany, France, Brazil, Mexico and Japan.

You can read it even if you don’t have a Kindle, by downloading Kindle for Mac or Kindle for PC. You can read it in your browser using Amazon’s Cloud Reader or you can read it on your mobile device, including the iPad, the iPhone or pretty much any device using the Android OS. In fact check out all the Amazon reading apps here.

Why isn’t #JaneAusten insane? In my book, I mean

That’s a question most authors of Jane Austen fan fiction don’t have to ponder. I think most people accept that Jane was a sane and sensible woman, but in my book, Jane, Actually, Jane’s sanity is something of a marvel because of the precepts and conditions of the world I created.

You can take a look at this page for the complete explanation of my world, but I’ll summarize here and mention that in my book, the dead can communicate with the living via the Internet. Those who died before the invention that made this possible, however, have spent their afterlives unable to communicate with either the living or the dead. They’ve essentially been doomed to a solitary non-existence, trapped in their own thoughts without the benefit of human companionship.

For Jane Austen, this means she’s been unable to talk to her friends, her family, her beloved sister, and after the deaths of those near to her, she was unable to talk to those generations who succeeded them. Further, she’s been unable to hear a spoken word in all that time or to taste or smell or feel anything.

I think any of you reading this would consider this a hellish punishment rather than the eternal reward most people expect or would desire. Some of my friends are aghast at the awfulness of the world I created, but I defend my decisions using the familiar dictum of tyrants and authors through the ages: Life isn’t necessarily fair. And that applies to the afterlife as well.

Of course a book about an insane Jane Austen would attract few readers (to be honest, a book about a dead Jane Austen who communicates via the Internet, also has attracted few readers), so I had to find some way to imagine a Jane who has preserved her sanity. I came up with the idea that in the first few decades of her afterlife, she was obsessed with the challenge of finishing Sanditon, the book she was writing after her death. It gave her a problem—an almost inconceivably difficult problem—to solve: how to write a book without the aid of pen and paper.

This is explained or referenced a few times in the book and I’ve explained it at my book readings, but what I’ve never mentioned until now is that I got the idea from an old Jimmy Stewart movie: Carbine Williams. This 1952 biopic is about the life of David Marshall Williams, who in the movie is portrayed as a North Carolina moonshiner who is blamed for the death of a federal agent. He goes to prison and endures brutal punishment, including solitary confinement. My memory is that Stewart was locked up in one of those tiny hot boxes left to bake in the sun, but I may be confusing that detail with another movie.

The main thing is that Stewart, as Williams, endures thirty days of this before he’s released. He spent far longer than any other prisoner in solitary and when he’s asked how he withstood the punishment for so long, he explains that in his mind, he took apart and put back together every gun with which he was familiar. Much of the beginning of the movie shows Williams’ rural upbringing and his expertise with firearms and that he was something of a backwoods tinkerer. He also conceives of a mechanism that in the movie at least, directly leads to the development of the M1 carbine, a lighter-weight cousin (truly they have nothing to do with one another) of the M1 Garand, the standard U.S. infantryman weapon of World War II.

The film made an impression on me when I saw it many, many years ago. It taught me the mind can be a powerful tool when a person is stripped of all else. You can imagine my surprise when I realized this movie about a North Caroline moonshiner in the 1930s provided the answer to preserving the sanity of my imaginary Jane Austen in the twenty-first century, almost two hundred years after her death in the English Regency.

Some of you, however, are not convinced, especially those of you reading this on your smart phone while simultaneously watching a movie on Netflix or Amazon. You probably can’t stand the thought of having nothing to do and the first one hundred and eighty five years of Jane’s afterlife sounds like the epitome of having nothing to do. I get frantic at the thought of eating alone at a restaurant without something to read, but some people get frantic at the thought of using a restroom without Wifi access. It’s almost inconceivable for many today that for much of humanity, there really wasn’t a lot to do.

I’m afraid it’s time to trot out “the past is a foreign country” quote again. It’s really quite difficult for a modern person to understand that for someone like Jane Austen, time meant something very different. I, for instance, quail at the thought of a car trip that takes more than thirty minutes and yet I can contemplate the thought of traveling several thousand miles and spending the better part of a day to visit England.

Jane, on the other hand, often took journeys that lasted several days and knew people who took overseas trips that weeks and months. She wrote books long hand on her little scraps of ivory and took about two years to do it (Mansfield Park, Emma and Persuasion). This is a feat I consider roughly analogous to performing one’s own appendectomy without anesthesia. I could not write were it not for the computer.

Jane also wrote letters and prayers and copied music by hand and possibly plays, or at least the parts that she or other family member would act in their performances at Steventon. She presumably memorized her parts and also the poetry of Cowper and Burns. She delighted her family by reading to them her own novels, which any teen of today would find mind numbingly tedious but which passed for entertainment in a time before texting, email and tweeting. Remember that Jane whiled away many an hour playing her cup and ball game and was proud of her accomplishment.

Memorization feats were still common in Jane’s time, although literacy and the printing press had made that less necessary. Still, I’m certain Jane could recite long passages when I’m hard pressed to recall the Gettysburg Address.

This was a time when people created their own entertainment, including sports, music and the all important business of dancing. Music also required a lot of effort, especially if you couldn’t play or afford an instrument. A lot of music had to exist solely in your head.

Authors are well suited to withstand the privations of the afterlife as I have defined it. If you’ve ever seen an author with that faraway look in their eyes, it often means they’re plotting. To help me fall asleep at night, I dream up plot lines for stories. When I ride my bike, I’m only half aware of the real world, which explains a lot of my accidents, but also some of my best plot lines. I think it perfectly natural that my Jane Austen would use her imagination to keep her sane.

None of this belittles my imaginary Jane’s accomplishment, however. It is still a wonder that she could have kept her sanity after all those years and indeed, many of the disembodied have simply given up on their spirit or have chosen to sit unmoving on a rock by a river thinking deep thoughts.

But an author, I think, always has a story to tell. And we all know the advice that an author should write what they know and have experienced. So imagine a Jane who has been observing the best and the worst of humanity for 200 years. Imagine the stories that she wants to tell. I think that’s why Jane Austen is not insane—in my book, I mean.

September 4, 2013

The “I Believe in #JaneAusten” buttons have arrived

You can get yours when you attend the 2013 Annual General Meeting of the Jane Austen Society of North American in Minneapolis this month. Or if you know someone.

You can get yours when you attend the 2013 Annual General Meeting of the Jane Austen Society of North American in Minneapolis this month. Or if you know someone.

Buy Jane, Actually in print from Amazon; get the Kindle copy free

Jane Austen is, of course, an avid e-book reader, but she does remember the thrill of holding her first printed copy of Sense and Sensibility, all those years ago. You too can have the enjoyment of holding a printed edition of Jane, Actually or Jane Jane Austen’s Book Tour, but until today, you had to pay extra for the convenience of being able to also read Jane, Actually as an e-book.

Jane Austen is, of course, an avid e-book reader, but she does remember the thrill of holding her first printed copy of Sense and Sensibility, all those years ago. You too can have the enjoyment of holding a printed edition of Jane, Actually or Jane Jane Austen’s Book Tour, but until today, you had to pay extra for the convenience of being able to also read Jane, Actually as an e-book.

Thanks to Amazon Kindle MatchBook*, however, readers who buy the print edition of Jane, Actually can now download a free digital copy of the book. It will behave just like a regular e-book and will appear in your Kindle library, whether you’re reading it on your Mac or PC or smartphone or tablet. The only thing your Kindle MatchBook copy can’t do is sync where you left off reading the physical copy, at least not until Amazon releases that implantable chip.

Amazon’s new program is a welcome boon to physical book readers who’d still like the occasional convenience of reading an e-book. Potentially any book you’ve bought from Amazon might now be bundled with an e-book, even books you’ve bought in the past. It’s up to individual publishers to activate the offer and set the price of the e-book. Mallard Press, the publisher of Jane, Actually, is offering the bundled e-book for free.

For a limited time†, Mallard Press will be doing Amazon one better. No matter where you bought your physical copy of Jane, Actually—from Barnes & Noble or even a real bookstore—you can receive a free e-book copy. Just provide reasonable proof of purchase—a receipt or a photo of you holding your book—to qualify. Fill out this form to start the process:

[contact-form]

* The program officially starts in October but is retroactive. If you buy the print book today from Amazon, you’ll have to wait until next month to download the free e-book.

† Offer good until it proves too difficult to fulfill.

August 28, 2013

On being slighted by the Doctor

By Jane, Actually

Thanks to patient explanations from my friend and avatar Mary, I have finally come to appreciate Doctor Who. Once I did achieve this appreciation, my irritation that the Doctor has never included me as a companion has been increasing steadily. To mollify me, Mary created this poster and said I could use it as the basis for a campaign for me to travel with the Doctor. I am delighted, but I think Mary just wants to be on the show.

August 15, 2013

Pride and Prejudice Thug Notes

By Jane, Actually

It is with considerable confusion that I write of the Thug Notes analysis of Pride and Prejudice that was recently brought to my attention. I do appreciate the meta-ness (as my avatar Mary Crawford called it) of a black man purporting to be a “gangsta” giving an insightful analysis of my novel of manners.

Sparky Sweets, PhD, if that is his real name, delivers a very quick description of the plot in colourful vernacular, which to me is rendered even more colourfully for I must enable YouTube captions in order to comprehend it. The resultant translation is almost incomprehensible. I must equate “dossey” with Darcy and “welcome” with Wickham in order to understand it.

Fortunately I maintain a service that employs a human translator to transcribe video and within a few hours, I was able to read a more realistic translation, although much still remained a mystery. Nevertheless I realized that Mr Sweets gave a workmanlike description of the plot and the characters, although much is understandably lost in a video lasting a mere four minutes and thirteen seconds. Simply calling Mr Collins “a rich preacher man” loses so many levels that I despair.

Mr Sweets’ analysis of the central theme of my novel is … well I can only make sense of it in a general way. He does say “moral blindness and self knowledge” are central themes and that is certainly true, but he also adopts the simplistic view shared by many that Darcy represents Pride and Elizabeth represents Prejudice. Or perhaps he is simply forced to take such a simple view because of his limited time.

Let me now return to my original comment that I am confused by this video. I am a long-dead member of the poor gentry of a once powerful country that simultaneously governed, despoiled, civilised and oppressed much of the world. I am unqualified to pass judgement on the appropriateness of a seemingly intelligent young black man pretending to be something he most likely is not giving his opinion of a work of fiction that some have been kind enough consider to be a hallmark of English literature.

I am unqualified to judge whether Mr Sweets’ presentation might actually induce someone to read my book (or any of the other books he has selected). I cannot say whether his offering does a service or a disservice to the impression or stereotype of young black men. My first impression was that this video is an unfortunate choice, but I think my feelings on first impressions are well know. The very fact that these videos have awakened such complicated thoughts is probably proof that there is some merit to this approach.

Or perhaps, and I say this with a slowing dawning epiphany, maybe I make too much fuss about something that is merely meant as a light-hearted entertainment.

Jane, Actually reading at the BookBar

Talking about the afterlife, Jane Austen and science fiction is best accomplished with a glass of wine, so join me at the BookBar, where I explain how the long dead author of Pride and Prejudice gets another shot at fame and maybe even romance.

7:30 p.m. Aug. 24 at the BookBar in the Denver Berkeley Neighborhood (near 44th and Tennyson).

August 7, 2013

Creating the afterlife

At my recent reading at the Tattered Cover, I began by giving people a quick introduction to the afterlife as I have conceived it in my book, Jane, Actually. I expected I could kill a couple of minutes afterward by asking the audience if they had any questions, but all I heard was crickets. That’s when I realized most people would require a little time to contemplate my conception of the afterlife before being able to ask a question.

That’s difficult for me to understand because I’ve been living with the AfterNet since I conceived of it circa 1995, or just about the same time most people became aware of the Internet and the World Wide Web. The “rules” governing my understanding of the afterlife erupted fully formed, but the antecedents go way, way back.

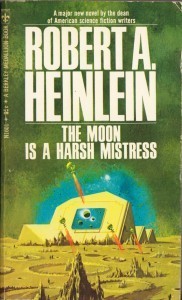

Probably the primal influence is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein. In his 1966 novel, the Moon is a breakaway republic that is aided by the Lunar Authority’s master computer (HOLMES IV), which has gained sentience. The computer, who calls itself Mycroft, creates a fictitious identity—Adam Selene—to be a George Washington figure and lead the Moon to independence from Earth. No one has actually met Adam Selene, but everyone claims his friendship. He is a virtual character who everyone assumes exists but only ever communicates electronically. He is a disembodied character. Like all great science fiction, the story asks what does it mean to be human. Can a conglomeration of circuits and logic boards not only achieve sentience but also be considered human?

Probably the primal influence is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein. In his 1966 novel, the Moon is a breakaway republic that is aided by the Lunar Authority’s master computer (HOLMES IV), which has gained sentience. The computer, who calls itself Mycroft, creates a fictitious identity—Adam Selene—to be a George Washington figure and lead the Moon to independence from Earth. No one has actually met Adam Selene, but everyone claims his friendship. He is a virtual character who everyone assumes exists but only ever communicates electronically. He is a disembodied character. Like all great science fiction, the story asks what does it mean to be human. Can a conglomeration of circuits and logic boards not only achieve sentience but also be considered human?

Another influence was a short story, the title of which I can’t remember. It might have been written by Harlan Ellison and was about a character so unpopular he might as well not have existed and that’s just what happens. There’s a similar episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer about a high school girl so unpopular she becomes invisible.

When you’re forgotten, do you cease to exist? Can you say that someone who died in the Middle Ages and of whose existence no one alive today is aware of ever exist? Now the simple mention of your name is noted by every alphabet agency of the federal government and consigned to some data vault in North Dakota. Do you have any more existence because Google has determined that you’re desperately in want of an Arts and Craft antique brass drawer pull than that poor villein from the Middle Ages?

Another science fiction inspiration for the AfterNet is Philip José Farmer‘s Riverworld series, where everyone who has ever died is reincarnated on the banks of the endless river that circles the Riverworld. The books feature Samuel Clemens and Sir Richard Burton the African explorer and the rest of humanity. Everyone, saint and sinner, is in the same boat.

My most literary inspiration for the afterlife is Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol:

The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley’s Ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a door-step. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.

This idea, that the dead lost the ability to interfere for good, is really the heart of my fictional world and reflects my general fuzzy-headed notion that despite Grumpy Cat and political invective and twitter hate mail just for proposing Jane Austen be on the £10 note, that the Internet is overall a good thing.

What if we could learn the Mahatma’s thoughts after being freed of his body since 1948? What if I could apologize to that friend who died and never knew that I am deeply sorry for what I said? What if Jane Austen could complete the book she was writing when she died?

Admittedly death won’t necessarily make one a better person. Hitler is undoubtedly just as vile after death and would probably seek power again, but would such evil be counterbalanced by those whose good works were cut short? Would the realization that rich or poor, black or white, good or bad, Muslim, Catholic, Sikh, Hindu, Baptist or atheist—would the realization that we all end up the same place, still on earth but apart from humanity, make any difference for good?

That was my original intent in creating the AfterNet. My first idea was to actually create the AfterNet: a place where the dead could communicate with the living. Not literally, obviously, but a place where one could assume the identity of a person who’d died and contribute to the conversation that might take place between an eighteenth-century Regency gentleman and a woman who’d died in 1241 when Wenceslaus I of Bohemia fought back the Mongol horde.

It was a silly idea, of course, but it did lead to me writing Good Cop, Dead Cop, in 2006, and then Jane, Actually in 2011. So I’ve been writing about a universe where everyone who has ever died potentially could converse via the Internet for a pretty long time, and it’s a pretty rich universe. I can tell the story of any person from all of time and place them in the here and now of the twenty-first century. My next book, The Background Noise of Souls, continues the story of Good Cop, Dead Cop, and I have other stories planned that take place in the world of the AfterNet. To me it’s a comfortable world, just like Larry Niven’s Known Space has been for him and for others who play in his world.

August 2, 2013

Review of Jane, Actually: “wonderful summer book”

Petkus does a marvelous job providing the disembodied Jane with a strong voice and a real personality–she can be funny, sympathetic, weary, egotistical, petty, loving, engaging, and wise in the way that only someone who has been a keen observer of life for the past 200+ years can be.

Fellow Denver-Boulder JASNA member Janet Smith has been exceedingly kind to post her review of Jane, Actually at her blog. And she’s giving away two paperbacks and two ebooks, so just leave a comment. And while you’re at it, check out my review of Jane’s book Intimations of Austen, or just take my word for it and buy it at Amazon. Jane has been reading Austen a lot longer than I have and her understanding shows.