Markus Gärtner's Blog, page 5

October 10, 2022

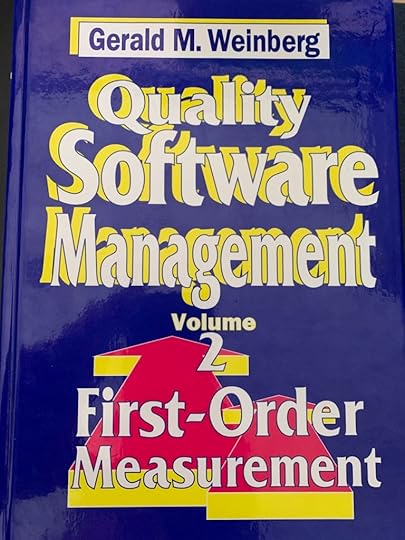

Remembering Jerry: Quality Software Management Volume 2 – First-order Measurement

It’s been four years since – sadly – Gerald M. “Jerry” Weinberg passed away. Ever since then, I struggled with some public mourning about him, until recently I had just the right idea. On a weekly basis, I will publish a review of a book I read that Jerry either wrote himself or is about some of his work. Today, we are going to take a look at what I consider the first book in Jerry’s seminal series on managing quality software: Quality Software Management Volume 2 – First-order Measurement published by Dorset House Publishing in 1993.

Review on Amazon

Review on AmazonA while back, I reviewed this book on Amazon:

Introduction to measurement systems in Software Development

In the second volume of the series, Jerry continues to dig deeper into the cultural model of software development organizations. Jerry presents a thorough discussion of the Satir Interaction Model. The Satir Interaction Model splits up communication into four major steps: intake, which is how I take in information; meaning, which is derived by making interpretations from the received message; significance, which is whether I start to bother or not; and finally the response on the initial message. All these steps happen in a fraction of a second in human communication.

The Satir Interaction Model is useful in situations where you start to make meaning too soon based on fractions of the data that you got. Often, this leads to misinterpretations about the intentions of your communication counterpart and therefore not only to poor dialogue but also to a big misunderstanding. That’s why Jerry raises the Rule of Three:

“If I can’t think of at least three different interpretations of what I received, I haven’t thought enough about what it might mean.”

In parallel to the discussion of the Satir Interaction Model, Weinberg continues to show the relevance of first-order measurements in management. Using systems thinking as introduced in the first volume of this series, he explains management actions and their results. He continues to dig into metrics that are useful for managing. Finally, he discusses zeroth-order measurements, that each management should be aware of. These measurements tell you which things to keep an eye on in order to manage your software project.

A blast from the pastLet’s see what changed in the 10+ years since then. Jerry structures the whole book around the Satir communication model. So, it basically separates into four main parts: Intake, Meaning, Significance, and Response. In the fifth and final part, he goes deeper into what he calls zeroth-order measurements and what kind of zeroth-order measurements he deducts from software teams and companies.

As the title suggests, Jerry distinguishes between different orders of measurement. Third-order measurements are “the kind of measurement that supports the physicist’s search for universal laws.” Second-order measurements “are used to optimize systems to make them faster or cheaper, to tune a machine to its most efficient performance.” First-order measurements “are just adequate to the task of getting something built.” They are “the measurements that allow us to build a machine in the first place.” Zeroth-order measurements are “a set of activities needed to start on a sure path to quality management of quality software.”

For the zeroth-order measurements, Jerry offers the following four steps:

Knowledge of how to compose a project of well-defined and measurable tasks to produce a quality product.a system of creating and maintaining a public view of progress on the project toward the quality desireda system of requirements that document what is meant by qualitya consistent system of reviews to measure every result of the progress toward quality.He also adds the Zeroth Law of Software Engineering:

If you don’t care about quality, you can achieve any other objective.

Quality Software Management – Volume 2: First-order Measurement, Gerald M. Weinberg, Dorset House, 1993, page 255

From this viewpoint, it makes sense for Jerry to mention so many things around the observation of people and helping organizations to look for the right things in their processes.

Just skimming through the mere three pages of laws and principles in the back, gives me chills. Almost every one of them is a gem on its own. Jerry managed to put together a deep resource here that is close to impossible to represent well enough. I sense, there are so many laws and principles I have come to value on their own and know by heart, that I oftentimes don’t even put the name to it or recalled I learned these lessons from him.

Quality Software Management Volume 2 is not only my most often-cited source of The Rule of Three Interpretations:

If I can’t think of at least three different interpretations of what I received, I haven’t thought enough about what it might mean.

Quality Software Management – Volume 2: First-order Measurement, Gerald M. Weinberg, Dorset House, 1993, page 90

but a whole bunch of others.

Some personal gemThe Rationalization Principle

Quality Software Management – Volume 2: First-order Measurement, Gerald M. Weinberg, Dorset House, 1993

You can design a measurement system for any conclusion you wish to draw. (page 35)

The Information Rule

No matter what else it is, everything is information. (page 58)

The Physician Principle

Every process is created by people, and thus can be changed by people. (page 59)

The Quality Problem

Every software problem is a quality problem. (page 111)

Chinese Saying

When you point a finger at somebosy, notice where the other three fingers are pointing. (page 161)

Satir’s Dictum

The problem is nothing. The coping with the problem is everything. (page 211)

The Acting Crazy Principle

When somebody is acting crazy, go to the empathic position and find a logical reason for the craziness. (page 230)

I’ll conclude this review with a personal gem that I posted as well on my Quality Software Management Volume 1 review.

After finishing the first or maybe second Quality Software Management Volume, I figured that Jerry kept a list of all the reminders for the readers in the book of the books. At some point, I decided to write them up and keep them for my personal references. In case you wondering, this is how I can relate to particular pages whenever I cite something from Jerry. I thought it would be neat to share this collection. I did not separate the different volumes into different files. So, here is the full list of laws, rules, and principles from the four Quality Software Management volumes. (And in case you are wondering, yes, I noted these down in LaTeX and compiled them into a pdf.)

Quality-Software-ManagementDownloadThese lists will probably only make sense to you if you read the books. Also note, that Jerry, later on, published an updated version of Quality Software Management, and I think he basically split each of the books into two or three smaller ones at the time. If you read those, the page numbers will not fit, and I don’t know how much he changed between the Dorset House and the later published ones.

October 7, 2022

The Deliberate Tester – Chapter 6: The Presentation

Back in 2011, I approached Rob Lambert at the Software Testing Club on a small series, packed into a narrative format as I wanted to try that out. Rob decided to run that series on the Software Testing Club back then, and I had some fun writing it. Skip forward 11 years, and the Software Testing Club no longer exists, it’s been a while since I have been in touch with Rob, yet I figured, let’s see how this series aged over the years. As a sort of throwback Friday for myself, I will publish the entries on a weekly basis, and read along with you. I think I ended up with eight chapters in the end and might add a reflection overall at the end. Today, April and Peter will present their challenge. In case you want to catch up with the previous parts, I published these ones earlier:

Chapter 1: Session-based explorationChapter 2: Facing the Business with AutomationChapter 3: Fallacies and PitfallsChapter 4: The ChallengeChapter 5: Logged InThe Deliberate TesterChapter 6: The PresentationAs the challenge approaches the end of the allotted timeframe, April and Peter get together to prepare a presentation on their course. Both know that they are asked to present their progress to the whole team. Since they admire most of the other team members, the perceived pressure for this presentation is quite huge.

“April, do you have an idea what we’re going to present?”

“I thought to show the login function, and have an exploratory demonstration with it.”

“This sounds good, but what about the things we learned over the course of the past two weeks?”

“You mean, how we paired up between programming and test? You’re right, this was the best approach to implement this screen.”

“So, let’s brainstorm a list of things that we might present.”

“Communication, collaboration, and fun.”

“This sounds like a good climax. Initially, we needed communication to get our heads together and reach a shared understanding of the login functionality. Then we collaborated together to get the screen implemented as well as the tests for it automated. And finally, we had a lot of fun doing so. I like that.”

“Ok, let’s write them on some cards.”

“Great idea. By then we can already get a feeling for our presentation. We may also just re‑order parts by shifting the cards around.”

“Yes, we also use cards during design meetings.”

“Ok, for the presentation, what do you have in mind?”

“Well, we could tell our story, and how we got together and improved our individual courses by then.”

“Sounds great. How about we start the tale with the first day and the initial version, that I tested?”

“Ok. I remember when Eric and you came to my office on that day…”

Peter and April finish the presentation in a few. The outline of the presentation foresees that they present the story of their small challenges first, and then demonstrate the login functionality to the whole team.

“Ah, I see you’re working on the presentation for tomorrow. How’s it coming along?”

“Hi Eric, yes, we’re making good progress here. We split it into two parts. The overall course and what we learned, and the second part will be a live demonstration using Exploratory Testing.”

“This sounds great. I’m looking forward to it.”

April and Peter are pretty nervous as they enter the meeting room on the day of the presentation. The whole team ‑ programmers, testers, as well as project managers ‑ got together in order to listen to their experiences.

“April, Peter, you worked on a small challenge over the course of the past two weeks. Please share with us what you learned during these two weeks.”

“We learned three basic things: communication, collaboration, and most important of all fun. Let’s take a look at each…”

April and Peter hold their presentation with great success. When it comes to the questions and answers part, the team members have a lot of questions.

“What have you enjoyed most about the communication?”

“Well, initially we worked separately from each other. When we first met and got our heads together, we figured out rather quickly that we got a different understanding of the functionality.”

“Therefore we sat together until we reached a common understanding. This helped us to a great extent during the next few days.”

“Absolutely, April. So, a shared mental model of the application was necessary to talk about the same thing and to make good progress.”

“Additionally, working together face‑to‑face helped in that. I don’t think we would have come up with a login mask mock‑up that early over the phone.”

“Absolutely true. So, for our next project, we’re planning to get heads together right from the start, and to reach a common understanding of the functions early on.”

“How did collaborating with a programmer feel? How about pair programming with a tester? Was he able to keep up with your pace?”

“Absolutely. Peter also surprised me with some interesting ideas to unit test my code. On a side note, I think I started to love testing.”

“The coding part was quite interesting to see. While we implemented the code, I started to think about gaps in the code, and how to approach testing the login mask with it. In addition seeing the unit tests helped me to get to know what already had been tested, thereby reducing the tests I wrote to the necessary bits. Being able to rely on tests that were already executed helped a lot.”

“Ok, let me see the screen. Let’s see if you missed anything…”

The presentation continues with the second part, the demonstration of the final login screen. April and Peter feel pretty proud as no one from the audience achieves to find any problems with the screen at all. The next week both get called into Eric’s office.

“April, Peter, first of all, the presentation you gave last week was absolutely fascinating.”

“Thanks, Eric. We weren’t that sure, but getting the feedback from the team was impressive to both of us.”

“Absolutely. Some of the insights you provided eventually influenced some of the managers around. They want to start locating testers and programmers together on the next projects, and see if they validate the results you achieved.”

“Wow, we were not aware that we delivered our message that well.”

“You did. You did an awesome job, and I wanted to thank both of you for that in person.”

October 5, 2022

On quiet quitting

Quiet quitting is a term that’s been floating around for a couple of months now. Yet, it stands for a concept that’s been around for centuries. Someone goes to work, and is less engaged than she used to be for some reason, eventually starting to look for a new job, and some months down the road you find that person leaving the company for greener pastures – maybe to be the worst on a team again and learn something new, maybe because life circumstances changed, maybe for another reason. Let’s explore my thoughts on this.

I recall my last job where I had sniffed some air from the agile world. Basically, my team replaced the whole test automation effort that grew over the course of a year. We worked in two-week cadences, held retrospectives at the end of each two weeks, and discovered the usefulness of pair programming and micro-level tests while integrating with a new test automation framework. One year later, our approach was still usable even though we worked on the third project with this automation framework by now. So, I was convinced by the value agile practices and principles had brought us, and I was eager to spread the word in that larger waterfall organization.

Despite my best arguments, really nothing sticked with the company. I recall consulting Elisabeth Hendrickson on this at some time. In her most honest way, she told me how she never managed to make meaningful changes in an organization by working there as an internal employee. Two months later, I had a job interview with my current employer, Twelve years on, I’m still there.

It did not take Elisabeth’s message back then for me to start looking for more agile employers. Maybe twelve or fifteen months prior to actually changing my job I started looking for other opportunities. Back then, I was thinking back and forth. There were better weeks, and there were worse weeks. Maybe I was slow to make the final move. But you could say that I quit quietly way prior to actually handing in my quitting notice.

What I recall feeling at the time was too little support, especially from others around me in helping spread the message. I had become a testing group leader a few years prior but wasn’t able to make my points stick. From this, there are two points worth exploring: my personal failures to get my points across, and what it meant to me when I handed in my quitting notice.

My contributionsI recall asking Martin Heider for some coaching at the XP 2010 in Trondheim. That was maybe three months before joining my new job. After explaining my circumstances to him, I was worried that basically the same would happen eventually at another company. Martin asked me just one question that blew my mind at the time: What’s your contribution to the situation?

Of course, back then I already had quit. That single question turned my thoughts back on me and helped me reflect on the situation. It was a basic reframing of the Chinese proverb:

If you point your fingers at another person, watch where the other fingers point to.

My perception is that the circumstances surrounding someone’s decision to quit a company have a cause of demotivation prior to it. Something is demotivating that person. Sometimes that person just stays demotivated for a long time, and despite their best efforts, is unable to get out of that situation.

There is a contribution of that person to the situation. Maybe that person is pushing too hard for a particular change, maybe that person is pushing not hard enough for a particular change. Maybe that person is communicating unskillfully or trying to resolve conflicts in unskillful ways. Or that person discourages others to participate in their idea by being too close-minded. Or that person is too open-minded while the environment around that person would need more guidance before being sold on the idea and able to contribute their thoughts to it. Maybe that person is taking communication too personal or not personal enough.

There is always a degree of our own contributions towards the factors that demotivate us. If we are able to find these sources, there lurks some personal growth for us. Maybe we can find a better way to push just gentle enough for a change to stick. Maybe we can find improvements to our communications, or get selfless with our initial ideas. No matter what, the period of quiet quitting can be helpful here if we reflect and curiously explore ways to improve our own contributions to our demotivation. Sometimes we can pull this off on our own, sometimes it needs help from a personal coach for example. No matter what, we can exploit the phase of quiet quitting to start to work on ourselves, and see whether that is helpful in getting re-engaged, and maybe not quitting at all.

But what if we see ourselves unable to tackle the personal growth potential in our demotivation over a prolonged time?

QuittingStick around long enough in the work field, and once or twice you may run into the phrase: People are not quitting the company, but the manager.

Knowing the responsibility process, this statement sounds like a form of blaming to me. Yet, I recall that I was certainly at such a point at some time before quitting. I recall being afraid to hand my quitting notice to my direct superior. He was a nice guy, and always had some ideas on how to move forward. On a human side, it just felt wrong for me to announce that I was no longer going to play along given the progress we had made on so many things in the past years. Yet, I sensed that I could grow further and faster upon changing jobs. So, to some extent, there was this attribution of the blame on my manager for not providing the environment where I could nurture and flourish.

So, whenever faced with a person quitting quietly, as a manager we should start to wonder what this person feels demotivated about, and maybe help to remove these factors of demotivation to have a chance for the person not leaving at all. Of course, there might be more to it than meets the eye, but the factors managers can influence most directly are the demotivating circumstances. That raises the chances, but it’s not a guarantee.

Over the years, at various companies, I have seen these dynamics repeat and eventually fail to some degree. People not seeing their growth opportunities in the first place, and managers not sensing the first signs of demotivation and having an open discussion about things to change in the organization in the second place. I always grieve a bit when seeing this dynamic play out to the conclusion that someone leaves the company. And I feel sad for the company not taking the growth opportunity to change its course. Quiet quitting is merely the second or third signal in this direction, and I think our workplaces would be better ones if we managed to listen to these signs when we see them occurring.

October 3, 2022

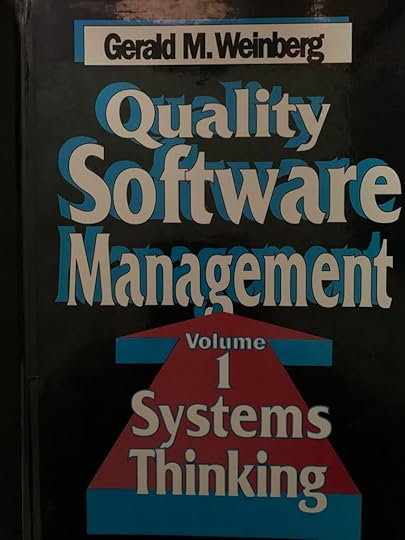

Remembering Jerry: Quality Software Management Volume 1 – Systems Thinking

It’s been four years since – sadly – Gerald M. “Jerry” Weinberg passed away. Ever since then, I struggled with some public mourning about him, until recently I had just the right idea. On a weekly basis, I will publish a review of a book I read that Jerry either wrote himself or is about some of his work. Today, we are going to take a look at what I consider the first book in Jerry’s seminal series on managing quality software: Quality Software Management Volume 1 – Systems Thinking published by Dorset House Publishing in 1992.

Review on Amazon

Review on AmazonA while back, I reviewed this book on Amazon:

The basis for managing towards Quality Software

In the first volume, Jerry provides the cultural pattern model and relates it to the CMM levels and other approaches taken. Interestingly his view includes the culture around the people actually producing the software in the first place, while other models focus on anything else but the people. First and foremost, Jerry defines quality as “value to some person”. Based on this definition, the question we have to ask in software development – which I define as programming, testing, and delivering – is whose values count most to us.

Additionally, Jerry introduces the reader to systems thinking. That is a model to think through difficult and maybe complex situations in software projects. He shows many graphs applying systems thinking, thereby creating deep insights into each of the cultural models, as well as the dynamics around the creation and maintenance of software.

Using systems thinking Jerry introduces the non-linearity of aspects of software development. He revisits Brook’s Law and generalizes it to hold not only for late projects, but for any project, when adding people, you’re making it more complicated, and maybe even later.

A blast from the pastLet’s see what changed in the 10 years since then. I recall that Jerry in Volume 1 came up with a taxonomy of corporations in the software development business from oblivious to “proficient”, but I don’t recall the exact terms. Looking them up, Jerry called them patterns with the following meaning:

Pattern 0: Oblivious When you do something in Excel or a spreadsheet, you may end up programming something without directly knowing that you are programming. Jerry calls this pattern of software sub-cultures oblivious to the fact that you are even creating software.Pattern 1: Variable Here, the company is aware they are producing software, but with variable results.Pattern 2: Routine The company worked on reducing its variability and producing software in a routine fashion with somewhat predictable resultsPattern 3: Steering The company is able to steer the quality of its software.Pattern 4: Anticipating The company anticipates changes and can deal with them.Pattern 5: Congruent The company acts congruent internally and externally and maintains the same congruent messages throughout.At least, that is how I would frame these patterns in my mind.

Of course, in Volume 1 – as the subtitle suggests – Jerry gives a brief introduction to Causal Loop Diagrams from the Systems Thinking field. Jerry describes a couple of his points in terms of causal loop diagrams and draws lines from effects to root causes and how they encircle a dynamic. Here in Volume 1 for example he draws a line for the effects of multi-tasking where he gives the following table:

Number of tasks% of Time on Each1100%240%320%410%55%more than 5randomA rule-of-thumb can help when estimating the effects of splitting tasks. the following table is what I use:

Sometimes you do better than this for certain people for short periods of time, but if you plan on doing better, your plan will fail.

Quality Software Management – Volume 1: Systems Thinking, Gerald M. Weinberg, Dorset House, 1992, page 284

In the chapter presiding this table, Jerry explores the causal loop diagram around deciding to ship a faulty product to the market or its users.

With his first volume in the Quality Software Management series, Jerry provides the reader with the basics of causal loop diagrams, which he continues to use in the next volumes to explain several aspects and drawbacks, as well as introduce the taxonomy used throughout the series. I consider it groundbreaking for the things to come.

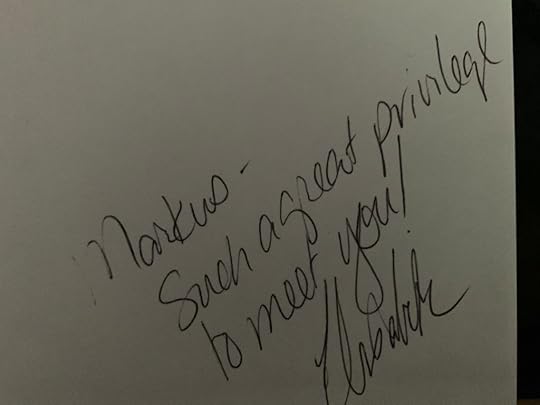

Some personal gemsI’ll conclude this review with some personal gems about my version of Quality Software Management Volume 1.

On the first Agile Testing Days 2009 in Berlin, I asked Elisabeth Hendrickson to sign my copy of Quality Software Management Volume 1, since she introduced herself as a student of Jerry during her tutorial session that I attended. I was reading Volume 1 back then, and since we followed each other on Twitter for a while, I figured it was a good way to keep memories of her.

After finishing the first or maybe second Quality Software Management Volume, I figured that Jerry kept a list of all the reminders for the readers in the book of the books. At some point, I decided to write them up and keep them for my personal references. In case you wondering, this is how I can relate to particular pages whenever I cite something from Jerry. I thought it would be neat to share this collection. I did not separate the different volumes into different files. So, here is the fill list of laws, rules, and principles from the four Quality Software Management volumes. (And in case you are wondering, yes, I noted these down in LaTeX and compiled them to a pdf.)

Quality-Software-ManagementDownloadThese lists will probably only make sense to you if you read the books. Also note, that Jerry, later on, published an updated version of Quality Software Management, and I think he basically split each of the books into two or three smaller ones at the time. If you read those, the page numbers will not fit, and I don’t know how much he changed between the Dorset House and the later published ones.

September 30, 2022

The Deliberate Tester – Chapter 5: Logged In

Back in 2011, I approached Rob Lambert at the Software Testing Club on a small series, packed into a narrative format as I wanted to try that out. Rob decided to run that series on the Software Testing Club back then, and I had some fun writing it. Skip forward 11 years, and the Software Testing Club no longer exists, it’s been a while since I have been in touch with Rob, yet I figured, let’s see how this series aged over the years. As a sort of throwback Friday for myself, I will publish the entries on a weekly basis, and read along with you. I think I ended up with eight chapters in the end and might add a reflection overall at the end. In case you want to catch up with the previous parts, I published these ones earlier:

Chapter 1: Session-based explorationChapter 2: Facing the Business with AutomationChapter 3: Fallacies and PitfallsChapter 4: The ChallengeThe Deliberate TesterChapter 5: Logged In“Ok, April, tell me about the business rules for the login.”

“Alright, Peter. Users may log in using a previously created username and a password. The username is given by the system administrator. Any letters or digits shall be allowed. The password has to include at least two letters, at least two digits, and at least one symbol, while being at least 8 characters long.”

“So, this is also checked at the login screen?”

“Yes. To avoid a security hole storing wrong passwords in the database.”

“In that case, shall an email be dispatched to the administrator?”

“Not in this iteration, yet. We will add that functionality in some weeks.”

“So, up until now we have got simple logins with valid passwords that should work, and we got some of the rejected passwords, and of course, we got invalid username and password combinations. What else is there?”

“That should serve as a first list of test ideas, yeah.”

“Alright, then let’s get these rules automated.”

“Let’s start with a password that is too short.”

“Shouldn’t we do the successful login test first? If the most obvious functionality isn’t working, then we don’t need to focus on rejected passwords at all.”

“Yes, you’re right.”

“So, let me sketch the first test.”

“Ok, Paris, but this looks too technical to me. Let’s try to rephrase the test in terms of business rules.”

“You mean, like what?”

“Here is what I have in mind.”

“Oh, that looks nice, really. Now that table reflects the business rules of the login very clearly, and we should be able to express login error test cases in a similar format very easily.”

“Yes, I didn’t think of failure tests so far. Let’s try to add some more successful tests first.”

“Ok, how about this?”

“Wait a minute. Does the username really matter?”

“Oh, you’re right. I think we can rewrite this by just listing up the valid passwords since the login result is the same all the time.”

“Yes, that’s even greater. But still, I think we may improve it. What do you think about this one?”

### Variables${aShortPassword} P4$sw0rd${aMediumPassword} MediumPassword12$${aVeryLongPassword} APasswordThatIsVeryLongAndContainsAtLeast2NumbersAndEven1Symbol%### Teststestsuccessful loginvalid passwords ${aShortPassword} ${aMediumPassword} ${aVeryLongPassword}“Now, that’s a bit more readable, but we also found an open question. What is the maximum length for a password?”

“Oh, we’ll have to clarify this. Let’s write it down on our notes, so we may get back to Eric with all the open points together.”

“Fine, now let’s take a look at passwords that should be rejected.”

“That looks fine. Let’s add some more passwords that should be rejected, and then we can bring in the automation code to drive these.”

“Yes, and we need to write some more tests for valid and invalid usernames as well. But I think we may re-use the format from the passwords by then.”

At the end of a busy day, April and Peter visit Eric’s office to show him their list of open questions.

“Eric, we made some great progress with the test automation today. But we also identified some open points regarding the functionality.”

“That sounds great. What about the open points?”

“Oh, we stumbled upon the question of what the maximum password length should be.”

“Ok, I’ll get you an answer tomorrow. So, how did collaboration between programmer and tester feel today?”

“It was fantastic. I’m sure we’ll have the tests up and running by tomorrow. That should also speed up our programming, as we can detect unwanted changes in related areas by then.”

“Awesome. I’ll see you tomorrow then, I suppose.”

September 28, 2022

My Arxta-Moment

Stick around long enough in the consulting business, and you might notice something I will coin the Arxta-Moment in this blog entry. I’m pretty sure, I’m not the first one to notice this, yet, I’m unaware of someone giving it a name. Let’s explore some history, and look for some advice from Jerry.

Craftsmanship over CrapUncle Bob Martin probably had his Arxta-Moment back in 2008. At the Agile conference, he held a keynote with the key message, that they forgot to include a fifth value pair in the Agile manifesto: Craftsmanship over Crap. Eventually, after the conference, he reframed it to really mean Craftsmanship over Execution, and the Software Craftsmanship movement started to form shape later in that year. I did not attend the Agile 2008 conference. Mostly, I read about the keynote at the time from Gojko’s blog.

Uncle Bob Martin was among the people at the 2001 Snowbird, Utah meeting where the group ended up writing down the Agile Manifesto. Basically, he organized the event and got the group together. Merely seven years later, Uncle Bob noticed that people became more interested in the latest tools around Agile development rather than trying to incorporate the message at the core of the whole movement. People and Interactions over Processes and Tools over the span of merely seven years had become merely a suggestion you don’t need to follow if you are a tool vendor – or find the excuse to work in a distributed company, potentially with more than ten teams, and more than ten persons per team.

Uncle Bob, in his keynote at the Agile 2008, tried to bring back some of the original ideas around the movement. Eventually, his whole movement sparked a new movement on its own.

ArxtaMerely a year later, another attendee of the Agile Manifesto meeting, Brian Marick, held a couple of talks on artisanal retro-futurism crossed with team-scale anarcho-syndicalism, or Arxta in short. If you want to know what these terms refer to, check out the talk from Marick on his site.

Marick’s core message here was, that Agile used to be about tearing down cubicle walls on the weekend because the team was convinced they could work better in this way. Over time, Agile became “at least my work does not suck as much as it used to”. In the talk, Marick tries to bring back some of the initial inspiration that sparked the whole movement.

Basically, Marick had quite similar concerns at the time as did Uncle Bob one year prior. I recall, at the time, I noticed other folks from the Agile field having similar thoughts. Joshua Kerievsky eventually came up with Modern Agile, Alistair Cockburn concluded with the Heart of Agile, and so on. I picked “my Arxta-Moment” as the title for this blog entry since I consider Marick’s points as describing the effect in the probably funniest way.

The Law of Raspberry JamAt some point, I noticed how all these Arxta-Moments I described basically have been described to some extent by Jerry Weinberg in The Secrets of Consulting:

The Law of Raspberry Jam

The Secrets of Consulting, page 11, , 1986, Jerry Weinberg, Dorset House

The wider you spread it, the thinner it gets.

Jerry describes that the more knowledge about programming started to spread, training programs for programming went from six weeks programs to three-day training, and eventually became thinner and thinner, or more shallow in the knowledge that was transferred.

You can see how this also applies to some communities and movements. The more people are exposed to the ideas in that movement, the thinner the original ideas start to get in all minds. I think that is what happened to the Agile movement, leading to fewer and fewer of the original ideas being discussed, and maybe repeating the same messages to newcomers over and over. The movement eventually ends up not advancing beyond the original ideas. Some of the early pioneers get discouraged from the topics the movement continues to discuss, and maybe they eventually move on to greener pastures with a new movement. In hindsight, it looks to me like this is exactly what happened around the timespan of 2007-2012 in the Agile community.

My Arxta-MomentOver the past years, I noticed how basically the same over time happened to the Software Craftsmanship movement and the German Softwerkskammer. At times, this motivated me to share some of the original ideas from the early discussions we had back in November and December 2008 that eventually lead to the formulation of the Software Craftsmanship Manifesto at the time. A couple of months after publishing the Software Craftsmanship Manifesto, someone noticed on the list that there were 100.000 or so signatories under the manifesto, and wondered what that meant. Someone on the list just replied: “This means there are 100.000 people fighting crappy code.”

That core message is still at the heart of my understanding of Software craft. That’s what I would like to continue to focus on when it comes to craft discussions. There are elements of Zeitgeist happening right now around the world that I don’t deny or would like to turn down, I merely would like to focus my efforts around the initial idea that motivated me to co-organize an unconference around the movement, and get back to exchanging thoughts on fighting crappy code. I appreciate Zeitgeist topics coming into discussions. In fact, in the early days, I recall Jason Gorman bringing up the topic of the gender problem in Craftsmanship, I think it was back in 2009 or 2010. I appreciate such discussions happening. However, I would like to get back to spending my time and energy fighting crappy code. That does not make the other topics irrelevant. It’s more of a prioritization question.

Probably I am following Jerry’s advice from More Secrets of Consulting here in the Lew of Strawberry Jam:

The Law of Strawberry Jam

More Secrets of Consulting, page 3, 2001, Jerry Weinberg, Dorset House

As long as it has lumps, you can never spread it too thin.

As long as some more people continue to fight crappy code, the movement is not spread too thin. Let’s see where this might lead to.

September 26, 2022

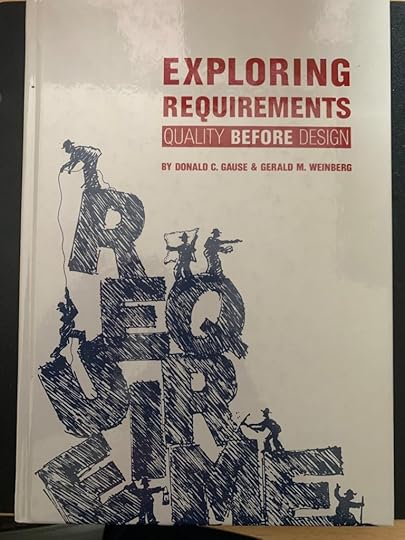

Remembering Jerry: Exploring Requirements

It’s been four years since – sadly – Gerald M. “Jerry” Weinberg passed away. Ever since then, I struggled with some public mourning about him, until recently I had just the right idea. On a weekly basis, I will publish a review of a book I read that Jerry either wrote himself or is about some of his work. Today, we are going to take a look at another book Jerry co-authored with Donald C. Gause: Exploring Requirements – Quality Before Design published by Dorset House Publishing in 1989.

Don Gause and Jerry Weinberg tackle many perspectives around the gathering of requirements in this book. To be honest, I don’t recall much of it years after reading it. The only exception probably is the mentioning of the Dictum in the Swedish Army:

When the map and the territory don’t agree, always believe the territory.

I recall that I reached out to Jerry once to find out about the origin of that Dictum to reference it properly. He basically wrote me back that the origin was personal communication, probably with someone from the Swedish Army.

Upon re-visiting the table of contents for this review, I start to notice that there is more that I regularly use from this book. Gause and Weinberg describe the difference between the problem space and the solution space. The problem space is the area where much of the domain knowledge stems from, and where a potential problem for a user of your system lies. The solution space is the space where possible solutions to a problem lie. If you overlap the two, there usually are several solutions to a given problem. The act of gathering requirements is to explore this overlap and find suitable solutions to a problem while keeping in mind all the other constraints and other solutions – narrowing down the number of solutions we want to implement to just a few.

While going through the table of contents to remember what I have read in it, I find a chapter on ambiguity and the discussion around context-free questions, that starts to ring a bell for me. When talking to users and customers, there may some ambiguity be lurking in the communication. I think this is also the chapter where the term Lullaby language was coined by Jerry. Lullaby language basically consists of terms like “all”, “always”, “never”, and the like. Gause and Weinberg motivate to narrow down these quantifiers in order to make our language less ambiguous. Gojko Adzic took on much of this in his Bridging the Communication Gap book, and later on as well in his Specification by Example book.

Context-free questions help to understand the problem space without judging too much about it. While talking to users and customers, it’s easy to suppose our solutions on them while these don’t solve a problem. Context-free questions help us to really understand the problem before trying to come up with solutions.

Of course, Gause and Weinberg also take a closer look at the quality aspects after requirements have been understood and how they will benefit from the gathering of requirements. They basically included chapters on other phases of the (classical) product development cycle, including technical reviews, test cases, and the like. Since Jerry wrote separate books about all these aspects, I recall having gained more from these subject-specific books.

In hindsight, I took much more from Jerry’s work in the Quality Software Management series or the Secrets of Consulting series with me. Maybe I will tackle these books in the upcoming weeks. Exploring Requirements, nevertheless, is referenced in a couple of ATDD and BDD books. Going through the book, I found a profound quote right at the beginning, that will also conclude this review:

There’s no sense being exact about something if you don’t even know what you’re talking about.

John von Neumann

September 23, 2022

The Deliberate Tester – Chapter 4: The Challenge

Back in 2011, I approached Rob Lambert at the Software Testing Club on a small series, packed into a narrative format as I wanted to try that out. Rob decided to run that series on the Software Testing Club back then, and I had some fun writing it. Skip forward 11 years, and the Software Testing Club no longer exists, it’s been a while since I have been in touch with Rob, yet I figured, let’s see how this series aged over the years. As a sort of throwback Friday for myself, I will publish the entries on a weekly basis, and read along with you. I think I ended up with eight chapters in the end and might add a reflection overall at the end. In case you want to catch up with the previous parts, I published these ones earlier:

Chapter 1: Session-based explorationChapter 2: Facing the Business with AutomationChapter 3: Fallacies and PitfallsChapter 4: The Challenge“Peter, you have done very well over the course of the last week.”

Peter sat in Eric’s office and was wondering what his boss would tell him after the first week of his first job after leaving the university.

“I would like to give you the assignment to do on your own. A challenge.”

“Ok, so no pairing?”

“Exactly. Considering your progress in the past week, by now you should know the basics in order to succeed at it.”

“Well, thank you for your confidence. I’m not that sure about it, yet. So, what is this challenge all about?”

“I want you to test a piece of software. You may use anything for the testing as you may see fit. You get two weeks for your preparations, planning, infrastructure, execution, and final report. In the end, I would like you to present your final report in a brown bag meeting to the whole team. It’s a tiny piece of a larger application suited for this kind of challenge. It’s a basic login screen for some web application.”

“Oh, that sounds great. When may I start?”

“You may start right away next week. In case you need any help, you can ask Jennifer and John. I planned for them to support you on this accordingly. I will send you the details about the application to test in a mail providing you with the documentation as well. Ok?”

“I can’t wait to get it started!”

“Great, then have a nice weekend.”

When Peter got back to the office on Monday, he opened the email from Eric and started to dive directly into the application. Eric had provided him with a URL to the application. As he started the browser, Peter was already thinking about the first test cases to exercise. Peter quickly took a piece of paper and set up the charter for the morning.

“How’s that application coming along?” Jennifer asked.

“Oh, I’m just setting up a charter to get to know the product. Exploring the product in order to make informed decisions about the particular test approach seems a good starting point to me.”

“Sure. But you should keep an eye for traps.”

“Traps?”

“Yes. In all of our testing, there is a high probability to fall for traps.”

“Traps…. hmmm, do you have an example?”

“Do you remember the bug in the UI we had last week?”

“Yes, I worked on the automation code for the build the day before. On that day I learned, that automated tests are not sufficient in themselves. We need to explore the product also.”

“Exactly. We pinpointed the problem in that session. We started follow‑up testing so that we could give the developers as much information as possible in order to have them fix the problem. Since the problem was familiar to me, we could track it down in no time. But, what could have happened if the problem was not that easily tracked down?”

“Oh, you’re right. We might have spent all day to find the problem. Thereby we would have ignored our charter while spending time on pinpointing rather than testing. So, that would be a trap?”

“Yes. There are many more out there. I don’t want to spoil you, though, rather I can’t. Just keep yourself aware. As every tester may fall for a different trap, over time you will need to find out how you get fooled yourself ‑ and prepare accordingly for it.”

“Thanks for the advice. I will keep that in mind.”

After 90 minutes following his charter, Peter felt uncomfortable with the state of the login functionality. He had come across a whole lot of bugs, his session report was full of problems. Therefore he decided to talk to Eric about his first exploratory session.

“Do you have a minute?”

“What’s up, Peter?”

“Regarding the challenge you gave me… Well, I explored the functionality this morning. It seems to be very buggy. Here, this is my session report.”

“Ok, can you give me a quick five-minute summary?”

“After having spent nearly all of the session trying usernames and passwords, there are serious problems in the interface. First off, when I enter the password field and start to type, the username field gets cleared. I can work around that issue by typing in the password first, but which user would do this? Second, it does not matter whether I enter a valid or an invalid username/password combination, they all successful login. And…”

“Alright. Did you talk to the developer? The login screen is actually a new functionality, which was started just today. I gave you the URL of the staging server, where the latest stable build is put on.”

“Oh, this is just developed right now?”

“Yes, April is the new programming apprentice. She got the challenge to develop a login mechanism.”

“Now I understand. You put us into two related challenges.”

“Yes, exactly. Ok, let me introduce you to April. I seem to have forgotten this one.”

As Peter and Eric arrived at April’s office, she just finished submitting her last changes.

“April, we just noticed that we didn’t introduce you to Peter. Peter is a new employee working as a tester on your challenge.”

“Hi Peter, nice to meet you. So, you’re testing the login screen then? I just pushed a new build to the staging server.”

“Oh, great. I spent some time this morning exercising the login screen on staging. I thought it was a production login. I noticed some areas, which could need some improvements. Shall we go through my session report together?”

“Oh, sure. Maybe we should sit together and coordinate our efforts. I’m not quite finished with it, but if you’re already testing it, you should at least know on which parts of the screen I’m going to work next, and which need improvements. Let me just finish my next Pomodoro off, then we can sit together in about half an hour.”

“Ok, that’s fine with me. Thereby I should be able to get some information from you on how to test the screen, whether we need regression capabilities using automated tests, and which areas are probably risky. See you in half an hour then.”

During that day, April and Peter made great progress. In the evening Eric visited them for a debrief.

“You’re still at Peter’s desk. It’s a great thing to see you two collaborating.”

“Yeah, we reached a common understanding of how to improve the login screen and how to test it.”

“Outstanding. Now, you have a plan for the next two weeks. April, what did you learn today?”

“Well, first I started to develop on my own without knowing what I was up to. Peter talked me through some alternatives, using familiar products he got to know over the internet. We agreed on some layout and functionality improvements. This has been fun.”

“Yes, exactly. It’s the same for me, too. At first, I was skeptical; April could bias my testing. But by getting our heads together, we were way more productive than on our own. We even agreed to pair program and pair test for the rest of our challenges.”

“Wonderful. I hope to see you two tomorrow for the debrief, checking about your progress. Keep up the good work.”

September 21, 2022

Automation with a human touch

It’s been a while since I read from Taiichi Ohno about the Toyota Production System and from Goldratt about the Theory of Constraints. Thus far I thought, both have close to nothing to do with each other. Today, however, I got an insight that brought the two closer together for me. Let me explain.

Some contextI am currently working on a client that deals with 6- or 7-joint robots, even in the industrial field. Today I worked with one of their teams on their product vision. They had identified customers as companies that want to automate portions of their work stream by bringing in a robot and teaching it some repetitive tasks, as well as users in those companies, people who teach the robot the movements it should start to do later on while working on several workpieces.

While coming up with value propositions, I brought up something I learned from Taiichi Ohno while he was setting up the Toyota Production System in the early 1950s and 1960s: automation with a human touch. Ohno argues that his goal never was to automate every step of a process, but maybe to make use of humans with creative brains aiding in automation.

I brought up how the robot can easily free the human brain from repetitive tasks in the work process, thus freeing the human brain from drought tasks. Instead, a trained craftsperson can inspect the workpieces that the robot has been working on and identify additional steps to apply maybe manually to finish off the coarse work that the robot easily repeated.

Theory of ConstraintsAs reflected in one of the wastes stemming from Lean, waste of human effort, it dawned on me, how this principle basically is applying Theory of Constraints Thinking to the problem of automation. Let me explain.

In the Theory of Constraints, every production process is limited by a constraint, the slowest or most time-consuming step in the production facility. The whole system cannot produce faster products than the constraint currently allows. Goldratt identifies five focusing steps to improve the system:

identify the system’s constraint(s): Identify the current constraint (the single part of the process that limits the rate at which the goal is achieved).Decide how to exploit the system’s constraint(s): Make quick improvements to the throughput of the constraint using existing resources (i.e., make the most of what you have).subordinate everything else to the above decision: Review all other activities in the process to ensure that they are aligned with and truly support the needs of the constraint.elevate the system’s constraint(s): If the constraint still exists (i.e., it has not moved), consider what further actions can be taken to eliminate it from being the constraint. Normally, actions are continued at this step until the constraint has been “broken” (until it has moved somewhere else). In some cases, capital investment may be required.Repeat the process: The Five Focusing Steps are a continuous improvement cycle. Therefore, once a constraint is resolved the next constraint should immediately be addressed. This step is a reminder to never become complacent – aggressively improve the current constraint…and then immediately move on to the next constraint.If the constraint in a production process is the creativity of a human crafter, one way to exploit, subordinate, and elevate that constraint lies in freeing the human mind from boring, repetitive tasks that break his creativity zone. So, if we bring in automation to free the human mind from the repetitive steps in that process, we make sure that the constraint of human creativity can be used to think about more problems.

Does this relate to test automation?I think this point can be related to the benefits you can get from following a balanced approach between test automation and exploratory testing as well. Make sure to keep that human touch though. In software testing, usually, there is close to an infinite amount of tests that you could potentially run.

As Doug Hoffman explains in Exhausting your test options, he was tasked in his career once with testing the square root calculations of a new floating point unit. In order to make sure all input values resulted in the correct results for 32-bit floating point numbers as inputs, he precalculated on another device the expected results, automated all 4 billion calculations with the new calculation unit, and let it run on the new computer. Through the automation, the execution took 5 minutes. He found two erroneous results.

Thinking forward to 2022, we currently deal with 128-bit floating point numbers in more modern computers. Assuming the same execution times would yield 1^40 hours to calculate (several millennia). Thus, it’s impractical to test all the values on a modern computer, and just consider how more complex than calculating square roots modern applications have become. In fact, the whole software testing theory mainly deals with ways to reduce the number of tests that you execute to some meaningful subset of all the tests you could potentially run.

As the story also illustrates, Doug Hoffman used automation to aid in his testing with a human touch. If automation takes away the boring tasks from the human brain cells, we can spend more time exploring what our automation did not catch. I came to realize how this as well relates to Theory of Constraints Thinking applied to software testing. And I began to realize how the similarities in other places of work have similar constraints.

Then it dawned on me, that the whole fear about automation taking away jobs from folks, is more an emotional one rather than a logical one. But maybe we need to dive into that distinguishment at some other point in time..

September 19, 2022

Remembering Jerry: Are your lights on?

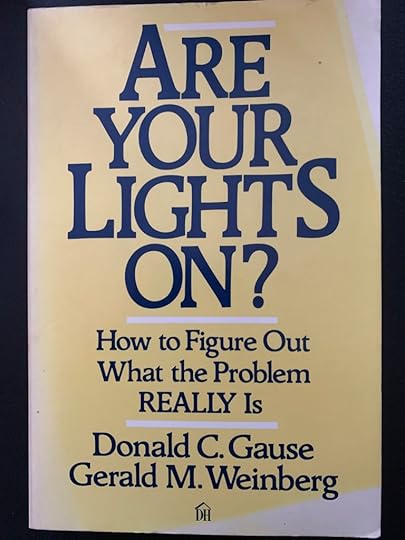

It’s been four years since – sadly – Gerald M. “Jerry” Weinberg passed away. Ever since then, I struggled with some public mourning about him, until recently I had just the right idea. On a weekly basis, I will publish a review of a book I read that Jerry either wrote himself or is about some of his work. Today, we are going to take a look at Are your lights on? – How to figure out what the problem REALLY is coauthored with Donald C. Gause. published by Dorset House Publishing in 1990.

Gause and Weinberg tell a couple of stories revolving around problem-solving. After each story, they summarize the lesson to take away from the story and generalize principles of problem-solving illustrated by each of the stories. To give you a glimpse of what these stories contain, probably the story behind the title is the most memorable one.

The story behind the titleA couple of years back, in the Swiss alps, there was a leisure vacation point where people would drive to, picnic or hike, and then return home. The road to that hiking spot went through a tunnel, and the district in charge of the tunnel became aware that many recreational visitors did not turn on their headlights while going through the tunnel, eventually leading to a series of car accidents. So, they thought of giving some directions to car drivers through that tunnel.

After weeks of negotiation and problem-solving, a group came up with a design for a sign at the beginning of the tunnel: “Turn your lights on!” They produced the sign, put it in front of the tunnel entries, and considered the problem solved. Only days after installing the sign, though, many recreational visitors started to complain about their batteries draining. The commission sought to take a look into the matter and quickly found out that many folks turned on their lights at the beginning of the tunnel, but never remembered to turn them off after leaving the tunnel, leading to drained car batteries while going on a hike.

In order to solve the problem they created, the commission went back to the drawing table and designed a sign for the exits of the tunnel. Applying a good Swiss engineering attitude, they came up with the following instructions, considering every possibility:

If it is daylight, and if your lights are on, turn off your lights.

If it is dark, and if your lights are off, turn on your lights.

If it is daylight, and if your lights are off, leave your lights off.

If it is dark, and if your lights are on, leave your lights on.

Hastily, they produced the signs for the end of the tunnel and put them up. Weeks later, the complaints continued, since no car driver ever could read that much of text while keeping an eye on the road.

The tunnel exit signs eventually got replaced by a sign with a single question:

Are your lights on?

The authors of the book explain their approach to problem-solving by basically asking three questions:

What’s the problem?Who has the problem?Who should solve the problem?In the first tunnel exit sign instance, the commission thought they needed to solve every problem car drivers would have while the car drivers really were the ones to solve the problem of their headlight being on or off after exiting the tunnel.

My main takeaways years after readingYears later, these three questions still stick in my brain whenever I encounter a problem a group of people wants to solve.

What’s the problem? What’s the problem behind the problem? Again, what is really the problem? Trying to solve a problem that is not well-enough understood oftentimes leads to haphazard solutions that only fix symptoms rather than root causes. I haven’t counted the times where a solution is put in place without understanding what the problem really is, only for the initial problems to appear again eventually, after much effort has been put into a solution that merely scratches the surface of the problem.

Who has the problem? Consider the people who are having the problem to start with. What would be acceptable solutions from their point of view? What would be unacceptable solutions? How are they going to incorporate the solution we’re thinking of? Will it meet resistance? All these questions are mandatory to understand unless you want to face a situation where a proposed solution is rejected.

Who should solve the problem? This point sort of blew my mind at the time. The person who has the problem is not necessarily the person that should solve the problem. Maybe some other person or group is way better equipped to solve the problem that exists for another person. Even today, I find this point at times at odds with concepts like The Responsibility Process, and the like. Thinking through the Responsibility Process you may conclude that “taking responsibility” for some problem that you have, means solving it on your own. I consider it to be taking responsibility even if you manage to persuade the group who really should be solving a problem to solve that problem, even though you are the one suffering from it. At times, I find myself in situations where others don’t agree with my thinking there.

I recall applying this same thinking a couple of years back. At the client at the time, there were some boxes of drinks freely available for anyone in the building. They had put the boxes with full bottles a bit separate from the boxes with empty bottles. At times I noticed how people continued to put their empty bottles into the boxes with full bottles, leading to some confusion, and oftentimes boxes of empty bottles among the boxes of full ones.

I noticed that the full bottles were placed before the empty ones. So, if you needed a new bottle, you would take your empty bottle, pick a new one, and put your empty bottle right in place. On one evening I shuffles the order of the boxes around, so people would first reach the empty bottle boxes before being able to get to the full ones. A week later, there were way fewer empty bottles among the boxes with full bottles. All of my thinking about the problem originated from the book Are your lights on.

As the story I shared regarding the title of the book showed, Are your lights on? is a pretty funny read at times, even though some folks may not be ready to make the leap towards the more general points regarding problem-solving. (I recall having a hard time on some of the points, depending on the mood I found myself in on the day of reading it.) Beyond that, it’s a pretty entertaining read, even if you don’t get the general points right from the get-go, and probably a book worthy to re-read anyways.