Jon Alston's Blog: The Year(s) After, page 2

January 26, 2015

A Look at Faith

Yesterday I spoke at Church. This happens sometimes. I don't normally share my religious side on here, but in the spirit of this new year, here is what I wrote (and then read) at church on Sunday:

* * *

Last week a friend of mine told me this story. Back when he used to work at a book store, he asked a female coworker who she thought was the most influential fictional character is on American society. Without giving any time for thought, she responded: “The Jesus, of course.”At first, I laughed when I heard this story, because I’d never even consider Jesus being a fictional character before. He has been a part of the history I’ve grown up with since I can remember. But since hearing that story, I’ve wondered how someone could believe He is merely a piece of fiction. A figure that is well known by most of the modern world as a good person and moral teacher, and although He may not be accepted as Lord and Savior, He is at least accepted as real. The more I thought about a fictitious nativity for Jesus, the more I started to see from this woman’s point of view; there is so little we really know about Jesus and His life. For a man who is supposed to be the Savior, almost nothing is known about Him. So to get at the heart of Jesus’ life, I went to James E. Talmage’s Jesus the Christ, since that seems to be the ultimate source of everything Jesus in the entire Mormon canon. I had yet to read it, only having been told it’s amazing. But, turns out that book’s over 700 pages long, so there was no way I was going to read it. I figured I could go with the next best thing: the Bible Dictionary. This is what is says about CHRIST:

Jesus, who is called Christ, is the firstborn of the Father in the spirit and the Only Begotten of the Father in the flesh. He is Jehovah and was foreordained to His great calling in the Grand Councils before the world was. He was born of Mary at Bethlehem, lived a sinless life, and wrought out a perfect atonement for all mankind by the shedding of His blood and His death on the cross. He rose from the grave and brought to pass the bodily resurrection of every living thing and the salvation and exaltation of the faithful. He is the greatest Being to be born on this earth—the perfect example—and all religious things should be done in His name. He will come again in power and glory to dwell on the earth and will stand as Judge of all mankind at the last day.

That’s it. Along with a list of other monikers He is known by. Although it eliminates a lot of the minutiae, this entirely summarizes all that we know from scripture about Jesus and His life. Include the modern revelations of the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, the Pearl of Great Price, and the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible, still what I know about Jesus is limited to the three years of His ministry, and most of that is limited to second hand accounts of lessons He taught recorded by the apostles. I know nothing about the first 30 years of His life after His birth.To be honest, I know more about the lives of Harry Potter, Frodo Baggins, and Luke Skywalker than I know about the life of Jesus. I know more about most fictional characters in books and movies than I do about Jesus. I even know more about the characters that I write than I do about Jesus sometimes. And I’m willing to bet most of you know more about fictional characters than you do about Jesus. I think most people do. It’s easy, really, there is so much information in this world about that which is not real, that which is untrue; it’s easy to know all about Emma Swan or Sherlock or Hobbits, because it’s everywhere. But Jesus, there is so little known about Him. The only record we have of His life is the New Testament and a few chapters in the Book of Mormon, and those are only biographical sources. We have nothing recorded by Jesus during his 33 years of mortality. With so little information, it makes since why someone might think Jesus is a fictional character, why someone wouldn’t believe in Him as Lord and Savior, why they would not have Faith in Jesus Christ.But what if we lived during Jesus’ time, or He lived out His mortal ministry during our time, would we believe in Him, would we have faith in Him? Would having his physical body in front of us convince us of His divinity? Would that woman change her view of Jesus as a fictional character? Would the rest of the world believe in Him and have faith?

Near the beginning of the book of John, Jesus discusses baptism with Nicodemus, but the concept of being born again, being born of water and of the spirit proves to be too difficult for Nicodemus to understand. Jesus says (John 3: 7-12):

7 Marvel not that I said unto thee, Ye must be born again.8 The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.9 Nicodemus answered and said unto him, How can these things be?10 Jesus answered and said unto him, Art thou a master of Israel, and knowest not these things?11 Verily, verily, I say unto thee, We speak that we do know, and testify that we have seen; and ye receive not our witness.12 If I have told you earthly things, and ye believe not, how shall ye believe, if I tell you of heavenly things?

Nicodemus stood face to face with Jesus, was able to ask him direct questions, but when Jesus spoke to Nicodemus of eternity, of the power of the spirit, Nicodemus could not understand, leading him not to believe the words spoken to him, and to not believe in Jesus. Although Nicodemus could not deny the physical tangibility of Jesus standing in front of him, he could deny everything else about Jesus and His teachings.Do we ever choose not believe in an aspect of the Gospel because we do not understand it? Do we choose to ignore the words of the Lord’s prophets because they are confusing or outdated? Do we, like Nicodemus, choose at times to not believe in Jesus?

On one of the occasions when Jesus was outside the temple, a group of Jews surrounded Him and asked (John 10: 24-39):

24 How long dost thou make us to doubt? If thou be the Christ, tell us plainly.25 Jesus answered them, I told you, and ye believed not: the works that I do in my Father’s name, they bear witness of me.26 But ye believe not, because ye are not of my sheep, as I said unto you.27 My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me:28 And I give unto them eternal life; and they shall never perish, neither shall any man pluck them out of my hand.29 My Father, which gave them me, is greater than all; and no man is able to pluck them out of my Father’s hand.30 I and my Father are one.31 Then the Jews took up stones again to stone him.32 Jesus answered them, Many good works have I shewed you from my Father; for which of those works do ye stone me?33 The Jews answered him, saying, For a good work we stone thee not; but for blasphemy; and because that thou, being a man, makest thyself God.34 Jesus answered them, Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods?35 If he called them gods, unto whom the word of God came, and the scripture cannot be broken;36 Say ye of him, whom the Father hath sanctified, and sent into the world, Thou blasphemest; because I said, I am the Son of God?37 If I do not the works of my Father, believe me not.38 But if I do, though ye believe not me, believe the works: that ye may know, and believe, that the Father is in me, and I in him.39 Therefore they sought again to take him: but he escaped out of their hand.

I have no doubt the Jews who questioned Jesus didn’t want to know any truth about Him, nor did they believe Him to be the Messiah. Their question was a means by which to trap Jesus in what they considered blasphemy, so they might rid Israel of the man who denounced their wicked ways. But like Nicodemus, even with solid evidence given to these Jews by Jesus of His divine nature and calling, they still refused to believe in Him. Though He be a tangible creature of flesh and blood, they believed nothing else about Him. They even denied their own scripture when quoted by Him. Like Nicodemus, they did not understand, and chose not to believe.

After Jesus performed the Atonement and was betrayed by Judas, the following morning the Sanhedran and chief priests of the church questioned Him (Luke 22: 67):

67 Art thou the Christ? tell us. And he said unto them, If I tell you, ye will not believe.

With Jesus standing in front of them, and the elders of the church asking him directly if he was the Christ, although mocking, they still would not believe Him. No matter what He did as proof of His divine nature and calling, the Jews would not believe. While Jesus hung on the cross, even then the people who watched his suffering did not believe in Him (Matthew 27: 39-42):

39 And they that passed by reviled him, wagging their heads,40 And saying, Thou that destroyest the temple, and buildest it in three days, save thyself. If thou be the Son of God, come down from the cross.41 Likewise also the chief priests mocking him, with the scribes and elders, said,42 He saved others; himself he cannot save. If he be the King of Israel, let him now come down from the cross, and we will believe him.

But Jesus did no such thing. And even if He had, they still would not have believed in Him, or His word. His flesh alone was not even enough for them.Lastly, after Jesus was crucified, lay in the tomb for three days, and then rose again on the third, still some did not believe, even those closest to Him (John 20: 24-29).

24 But Thomas, one of the twelve, called Didymus, was not with them when Jesus came.25 The other disciples therefore said unto him, We have seen the Lord. But he said unto them, Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and thrust my hand into his side, I will not believe.

Thomas, who was an apostle, knew the other apostles, who walked with them, taught with them, watched Jesus perform miracles, when they told him that Jesus had risen, he did not believe. Even though Jesus prophesied to the apostles about his death and resurrection, even though Thomas knew that Jesus was the Christ, the Son of God, even though he knew Jesus on a personal level, he still did not believe.

26 And after eight days again his disciples were within, and Thomas with them: then came Jesus, the doors being shut, and stood in the midst, and said, Peace be unto you.27 Then saith he to Thomas, Reach hither thy finger, and behold my hands; and reach hither thy hand, and thrust it into my side: and be not faithless, but believing.28 And Thomas answered and said unto him, My Lord and my God.29 Jesus saith unto him, Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed.

That is what it means to have Faith in Jesus Christ. Thomas would not believe that Jesus had risen from the tomb until he saw Jesus and touched the prints in His hands and the wound in His side. Only when Thomas received that physical manifestation that Jesus had in fact risen from the grave, only then did he believe. And how easy it must have been for him to believe. To have Jesus standing before him, clothed in white, perfected and whole. It would have been impossible for Thomas to doubt then and there that Jesus was the Son of God.We, unfortunately, do not have that luxury. At least I know I don’t. I have not seen Jesus, nor do I expect to in this life. But I believe that Jesus lived. I believe that He was born of the Virgin Mary, that He performed the miracles recorded in the New Testament and the Book of Mormon. I believe that he performed the Atonement in the Garden of Gethsemane, died on the cross on Golgotha, and rose out of Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb after three days. I believe that Jesus is not a fictional character, but the Only Begotten Son of God in the flesh. That is what faith in Jesus Christ is. It is believing that He actually lived, that He is real, and that He still lives.

Published on January 26, 2015 19:12

January 1, 2015

This is not a New Year's Resolution

But things need to change.

What I mean is that so far all I’ve done on this blog, and in many of my stories, is write about ideas. Long, boring, sometimes complicate, always pompous, extremely exclusionary, and terribly nearsighted ideas. The thing about all that, no one cares. And that is no woe is me statement, only a simple observation, and a truth that I intend rectify.

Don’t get me wrong. Ideas are great. In fact, thinking about ideas is my favorite pass time. And ideas can change the world. Every action was first a thought; and without thoughts, without ideas, we are nothing but carbon husks wrapped around skeletons waiting for our skin to melt off with age.

But as silly as it sounds, what I write is all that I get to leave behind for my friends and children. Leaving a trail of idea crumbs speaks very little to who I am and what I believe and how I feel. Ideas say nothing about my faith in God, my love for my wife, my fears about almost everything, the surprising fun I have being a father, and how important friendship is to me. They say nothing about me. Because ideas have no personality; all they can do is stimulate the brain, and maybe help a person get through a day of work.

My new goal for life (not just 2015) is to write better. To write about what I care about as a person; not the ideas I care about, but the objects, the people, the places, the feelings. To take all the pieces of me and reconfigure myself into words (if that’s possible). This will be new for me, an experiment that I hope will change the way I think and act and speak and create. An experiment that I hope will change my family, too, a change that will bring us closer together and help us to escape the confines of habits and desires that, at our cores, we loathe.

This will be new. And with new comes many faults. I will not do well with this, at first. I will complain. I will be boring. I will be self-indulgent and narcissistic. I will be depressing, and sometimes unpleasant. But somewhere in-between, I hope to uncover something beautiful for myself, and for others.

Published on January 01, 2015 19:06

December 21, 2014

Empathy (part II): The Writer . . . sort of

I've had this post done for almost a month now, as a follow up to the first about Empathy. It was going to be even better than the first, make a bunch a brilliant points on the subject, add more clarity to my already proposed suspicion on the word Empathy. In short, it detailed how the writer is simultaneously a Masochist and a Sadist, the one feeding the other. How the writer takes pleasure in creating characters and scenes of misery, sorrow, death, destruction, all things negative (and yes, I know some writers also write happy thing) while also enjoying the ability to inflict the pains of those experiences on readers. It was going to be my opus.

Then I read over it again.

And again.

I couldn’t figure out what it was, but the whole thing was just off.

So I let it sit for a few weeks. Then read it again.

Still, something was just not right. All the awesome ideas and conjectures and conclusions were right, they were clear, and they would change everything. I left nothing to chance, making sure that the progression of how a writer is a Sadomasochist could not be argued.

Then this morning I realized: who cares? Who cares what I think about Empathy? Or anything? As a writer I should know better. The job of the writer is to show the reader all things, including the writer's thoughts and feelings about life, the universe, and everything. Not to explain them. That’s all I’ve been doing on here for the last few years, explaining myself, my experiences, my thoughts and ideas and ideals. I’ve been telling.

No more telling. Hopefully. I’ll just end with two quotes that were going to be in the original post by one of my creative writing professors:

“The only job of the writer is to make the reader see.”

“You should care about what you care about, write about what is important to you.”

Published on December 21, 2014 18:22

November 3, 2014

Empathy (part I): Masochism

I have a complicated relationship with the word Empathy. In past posts I have skirted the issue of Empathy, touched briefly on my distain for the word, but I have yet to explore my reasons for disliking (in the nicest of terms) the word Empathy, and what that means, etcetera. You will find this word capitalized throughout, because I believe that is, on a whole, how the English speaking world views its importance.

But first: why do I harbor a loathing for the word Empathy? Because Empathy, in referring to the meaning of the word, does not exist; or, more succinct, it is impossible. Let us look at some definitions, so that I can try an explain myself (I attempted to pull from various sources for definitions and such, but Merriam-Webster just dominates my bookshelves):

Modern English Usage, by H. W. Fowler (1926)This guy devotes no space in his book for the word Empathy. I am uncertain as to why, but there it is. This is important because it signifies one of three things: one, the word’s usage was well enough known and used for its defined purpose; two, that Fowler cared so little for the word as to omit it from his text; or three, that the word was in little use and therefore required no attention.

Webster’s Dictionary of Synonyms (1951)This text also skips over Empathy, suggesting to me that there are no other words that can possibly resemble Empathy’s meaning. Again, there are two possibilities here: one, that the word is so specific and acute in its meaning, that no other word/words can resemble or clarify its meaning; or two, that Empathy as a word is not possible, because there is no other way to understand the word except in its own self-existence. The text does, however, contain the word “sympathy”, offering the following as synonyms: attraction, affinity, reciprocality, correspondence, harmony, consonance, accord, concord, pity, compassion, commiseration, ruth, condolence, empathy, bowels, tenderness, warmheartedness, warmth, responsiveness, tender, kindliness, kindness, benignness, benignancy, kind.

A Dictionary of Contemporary American Usage (1957)Another text that does not contain the word Empathy, nor sympathy. I am certain there is some intriguing research that could be done on why these texts do not contain this words, but the drive is not there for me, so someone else will have to do it for me.

The new Webster Encyclopedic Dictionary of the English Language (1971)-Greek empatheia, from em, in, and pathos, suffering, passion.-The imaginative projection of one’s consciousness into the feelings of another person or object; sympathetic understanding.

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (1998)1: the imaginative projection of a subjective state into an object so that the object appears to be infused with it;2: the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another of either the past or present without having the feelings, thoughts, and experience fully communicated in an objectively explicit manner; also: the capacity for this.

The American Heritage Dictionary (2001)-Identification with and understanding of another’s situation, feelings, and motives.

Dictionary.com1: the intellectual identification with or vicarious experiencing of the feelings, thoughts, or attitudes of another. 2: the imaginative ascribing to an object, as a natural object or work of art, feelings or attitudes present in oneself:

Merriam-Webster Online-The feeling that you understand and share another person's experiences and emotions: the ability to share someone else's feelings;1: the imaginative projectionof a subjective state into an object so that the object appears to be infused with it;2: the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariouslyexperiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another of either the past or present without having the feelings, thoughts, and experience fully communicated in an objectively explicitmanner; also: the capacity for this.

Oxford Dictionary Online-The ability to understand and share the feelings of another. Origin: early 20th century: from Greek empatheia(from em- 'in' + pathos 'feeling')

Thesaurus.com (it’s main comparison to pull this list of words was “understand”)affinity, appreciation, compassion, insight, pity, rapport, sympathy, warmth, communion, comprehension, concord, recognition, responsiveness, soul, being on same wavelength, being there for someone, community of interests, cottoning to, good vibrations, hitting it off.

Throughout the decades (at least what I have on my shelves and searched on the internet), the word has changed very little, if at all. In the simplest terms, Empathy is the act of one human vicariously experiencing/understanding the experiences and emotions of another human. That’s the problem I have: that we think we can understand the experiences of another; that we think we can vicariously know what it is like to go through something without ever partaking in said experience. Even if we have traversed a similar event, say the death of a parent, Empathy is still impossible. Which parent was it? How did the parent die? Was it cancer? Old age? Drugs? A car accident? An almost limitless litany of possibilities can separate us.

For argument’s sake, however, let’s consider that two individuals of the same sex and gender identification (to allow for the most similarities) have a mother that dies when they are 17 and the conditions for both are as follows: mother developed breast cancer in her early 40s, fought the debilitating disease for two years with extensive chemotherapy, died in the hospital (we’ll even say the same hospital), and was then buried in the local town cemetery. And let us assume that all other circumstances too numerous to list surrounding the deaths are exactly the same in both scenarios. Even in this example, Empathy is impossible, because Empathy will presume that both children have had the same day to day lives for the previous 15 before the mother took ill, and the same two years during her illness. That is not possible. We are not compartmentalized creatures, we do not and cannot separate experiences in our lives from others. Each second we live is informed by the entirety of our life lived previous to that second, a continuous updating of our personalities based what we try to define as the present. We are compilations of experience. We are variegated beings, unknowable even at times to our own consciousnesses. As much as I have a difficultly believing that every human on the planet is a unique individual, the sum of all personalities possible is infinite. No two people are exactly alike. Of course similarities are possible, even expected, but similarities are not exactitudes.

The trouble is we often confuse Empathy with sympathy, which is a gross misunderstanding. Sympathy is: an affinity, association, or relationship between persons or things wherein whatever affects one similarly affects the other. Unlike Empathy, sympathy does not pretend at individuals being able to comprehend the lives of each other, but instead indicates that we are emotionally connected, that the sorrow or joy of one affects the sorrow or joy of another, which is not only possible, but necessary. Sympathy is essential. It is vital to the existence of the human race. If we did not have sympathy, no one would have reason to care for or even consider another person, all would eventual devolve into chaos and disorder, selfishness would overpower all other emotions, bringing down humanity as a whole. We need to care about each other in order to keep the world functioning (if we want to keep humans on the planet). Sympathy binds us together in families, in marriages, and in friendships. Sympathy is was keeps total anarchy and slaughter from reigning. Sympathy is what makes us human, it is what separates us from other animals (in theory).

But Empathy, well, Empathy does not exist. Because in short, Empathy is not possible. Simple as that.

Now, to get to my point. What intrigues me (or confuses, or perhaps disgusts, I have yet to decide), is that we believe we have Empathy, or more accurately, we WANT to have Empathy. We WANT to feel the pain of others. Not all of us, mind you, but a large portion of humans on this planet DESIRE the pain of others, to know what others feel, to know why others feel what they feel. Since it is not possible to experience every feeling, every scenario, possible, we yearn for the pain and suffering of others, to fill in the gaps in our experiences (we do not consider someone Empathetic who can feel happiness with others, we use the term when someone is exceptional at feeling the pain of others, hence I focus on the negatives aspects of human relations when discussing Empathy). I believe it is why we read, watch movies, listen to music, view art, spend hundreds of hours just talking to people, study the sciences of the brain and culture, why we crave history; we want to feel the pain of others.

This brings me to the whole point of this tirade: Empathy is just another term for Masochism. Masochism is (in the non-sexual meaning): pleasure in being abused or dominated: a taste for suffering. Perhaps Empathy is not a pleasure, persay, but it is a desire for suffering. Empathy is the act of taking upon ourselves the pains of another, without experiencing that which caused the pain, and without being able to remove the pain from who we are vicariously living the experience. Empathy is a willingness, and I say a desire, to share the pain of another, especially when that pain cannot be shared and has no need to be shared. There is an attraction towards the suffering of others, to say “I know what you are feeling, I feel it too” even when we do not, or cannot. We want to feel that pain. We want to feel that suffering. It is almost reaches the level of pleasure to say that we are Empathetic, that we carry the pain and suffering and misery of others, or that we have the propensity to deprive ourselves of happiness to be like one who is struggling. Empathy is not sympathy, seeing others experience difficulty which in turn makes us sad for them, not in the least. Empathy, this masochistic conjunction, attempts to recreate the horrors of living that another has experienced, in someone who has not traversed said horrors (just ask Leopold von Sacher-Masoch). I do not understand such a desire. Life, whether you believe in a God or not, is about being happy; finding that which uplifts your consciousness and enlivens the body. Why, then, do we aspire towards Empathy? To our own self-inflicted pain and destruction? What does it do? What do we accomplish? We think we are becoming better people: better friends or siblings or lovers or whatever, because now we know what it means to be someone else, how it feels to be the ‘other’. Except, we do not. We are still, and forever will be, stuck inside our own flesh, our mind encased in fluids and bone interpreting external stimuli and converting them into electronic pulses that somehow get translated into what we call meaning. That neuronic electricity cannot be translated by another human brain. We can study it, even try to map it on computers and determine what pain and joy and confusion and creativity and so on, look like in the brain, but we cannot connect one brain to another. Whether by God or evolution, we have been placed in separate bodies for a reason. That reason being far too complicated for my personal understanding, but in the very least I believe it is because no one body can handle the full encompassing sorrow and pain that is human existence. Our weak flesh cannot handle such an overwhelming burden.

Empathy is the attribute of a God, an immortal perfect being capable of handling the immense pressure that true Empathy requires. The ability to literally, metaphysically, and metaphorically enter into the minds and hearts of others, to lift the weight of hardship. That is Empathy, and man cannot hope to come close to such a feat. We may aspire towards Empathy, to one day be able to physically handle what it means to be Empathetic, but as mortals, as fallible flesh, our attempts at Empathy are nothing more than masochistic endeavors fulfilling selfish desires.

Published on November 03, 2014 11:08

September 12, 2014

The Musicality of Punctuation

I’ve been trying to write this for months. But every time I flex my fingers over the computer keys, something gets in the way. First, it was this infographic a professor posted on Facebook months ago:

Brilliant, to say the least. My first thought: “I wish I had that in college.” And my second thought: “This will be great to use with my students.” And then I realized, looking it over, that I hate grammar, and more importantly, the arbitrary rules of punctuation used to explain grammar. And even more importantly, I don’t teach anymore. But I digress.

Then, last month I saw this video that Weird Al posted back in July of this year:

Also brilliant. I love Weird Al’s witty disdain for society’s failures (and if you don’t, you’re just lying to yourself).

Then I moved to Idaho (which is a whole other story).

Anyway. If I put this off any longer, what I have to say will already have been said. Hopefully it makes sense written down, because it does in my head.

GRAMMAR

So. What is the point of grammar, anyway? I mean, really the point. Or for that matter, textual communication in general? From all that I’ve learned so far in my short life, text is the means by which we represent speech. For thousands of years humans spoke without written language: developed grammars and complete languages, with none of it written. Then, someone thought it would be a good idea to start carving shapes into rocks and clay, on wood, and then eventually paper. All of which led to where we are now with typewriters, computers, cellphones, etc. Grammar, of course, is not a byproduct of textual language; but text does present the ability to more meticulously dissect, analyze, and debate it. For hundreds of years, at least in English, we’ve had roughly the same grammar, thanks to the unification that text-type creates. The last hundred years have really solidified what we now teach in schools as technology has attempted to control textual language (i.e. Microsoft Word). However, through this exacting of textual language, we’ve lost the original (and I believe more important) purpose of punctuation, grammar, and language: to represent the spoken idiom. Text serves no other purpose than to represent our verbal communication. It has never been a means by which to replace it. To control how we speak. Only an endeavor to capture the intricacies of human sound.

PUNCTUATION

But we don’t speak with punctuation. Now, I can only attest for myself, but I do not think about commas and semi-colons and periods when I’m speaking with my friends or family or whomever. Nothing of the sort.

As a child, I loathed Language Arts. The title itself made no sense to me. How is punctuation and sentence structure diagramming art? Or language? Or anything that an elementary school students would care about or want to practice? Point being, I never understood or learned proper grammar and punctuation usage until Graduate School.

In the U.S. we are taught that punctuation serves one purpose: the grammatically correct organization of written language, as deemed acceptable by dead white men through thousands of years of trial and error and debating. It was not something to be read, but only a way to separate ideas on the page. Grammar, to me, is something to loathe, because it makes no sense. There are rules. Lots of rules. Rules that even the best grammarians really don’t understand. Independent and dependent clauses, conjunctive phrases. I would list more, but I don’t know any, because I don’t care. Punctuation made grammar possible, as I saw as a child. But even after taking a History of the English Languageclass (one of the coolest classes I ever took, and one that I think all English speakers need to take in order to understand the language we speak and write), I still don’t understand why we perpetuate most of the grammar rules we use today.

As a creative writer, however, punctuation is very different. The rules aren’t as concrete, or adhered to at all sometimes for that matter. Punctuation, to the creative writer, is about breath. It’s about rhythm. Joseph Campbell said this about mythology: “Mythology is the song. It is the song of the imagination, inspired by the energies of the body.” As writers, we are constructors and participators in this Mythological song. We are the musicians of imagination. We create voices and scenes and experiences in the minds of others. That’s our goal. We manipulate little black symbols representing phonetics representing meaning into stories that have the power to alter an individual’s perception of their own reality, and the world, and universe in general. But, in order to facilitate that interaction between writer and reader, these symbols need some sort of organization, agreed upon by those who use them.

Which brings us back to grammar and punctuation. And the unfortunate need for it to make meaning possible. Sounds contradictory to what I’ve already written, but such is life.

I’ve thought a lot about this, especially in the last year while trying to teach English Composition college students how to write. Then, the epiphany. Like a bolt of lightning struck my brain. Text is nearly the same as musical notation. The notated song of speech. I came up with a musical analogy for punctuation, and although it’s how I explain creative writing, I think this rule really applies to all written language (not only in English, but then again, I know next to nothing about other languages). I believe punctuation can be understood through musical notation. Just as each note/rest represents a specific beat/pause length within a measure of a song, so does each syllable/punctuation mark represent a specific beat/pause length within a sentence. I only want to focus on punctuation, because syllabic rhythm and beat timing in words is something else entirely.

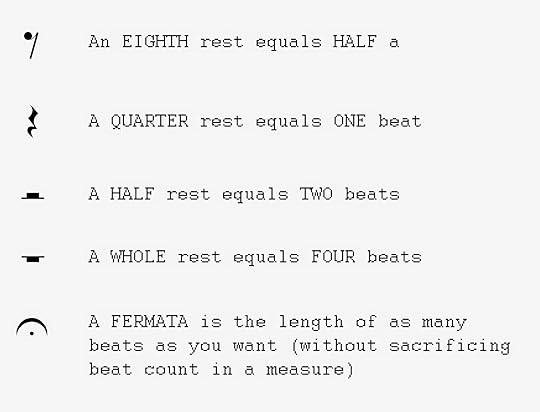

In standard 4/4 time (which for the musically illiterate, means four quarter notes [1/4] per measure: it’s all about fractions, remember 3rd grade?), the following is true for rests:

There are more rest types, but they are shorter pauses more suited to speaking rather than punctuation. So. How does this all relate to punctuation? As I mentioned, we are taught in the U.S. that punctuation serves very specific grammatical purposes that must be memorized without intuition to help guide exact choices. And don’t forget the exception to every single rule that you learn; multiple exceptions, in fact. This is what happens when there is a disconnect between the arts and sciences (just trust me on that). In order for this music analogy to work, you have to unlearn what you know about punctuation. Forget independent and dependent clauses, adverbial and prepositional phrases, etcetera. Just take a moment to unload that information, it’s okay, you’ve got time. This isn’t going anywhere.

Okay. Mind clear? Good, because I’m not going to explain what each punctuation mark is taught to be, I am only explaining how I see punctuation, and how I believe it should be used. The following is my list of all the common punctuation that any one might use in a given essay, email, Facebook post (if you use punctuation at all online), stories, and so on. The punctuation that is read. There is a catch, however: you must have some sense of rhythm, of the flow spoken words follow; although you may be writing, every read word is spoken by the internal narrator of each reader, including you. So keep that in mind.

EIGHTH REST = , COMMA — EM DASH – EN DASH: these allow the reader to catch their breath, without losing any momentum. The EM and EN DASHES function more as information asides rather than serious punctuation/rhythm markers, but still have some sense of resting.

QUARTER REST = : COLON ; SEMI-COLON (PARENTHESES) [BRACKETS]: the colon and semi-colon find themselves between the comma and period in length of breath-stop, where there is a small amount of time given to these two punctuation marks to allow the reader time to consider the information that has preceded these marks before proceeding to the next half of the sentence. Parentheses and brackets, however, do not only affect sense of breath, but of volume too (which will have to be for another post), almost like softening of the voice, a whisper from the writer to the reader, a secret that may not be needed, but adds to the story; these both vary on the intent of the author, which should be visible through context of the sentence/paragraph/story.

HALF REST = . PERIOD ? QUESTION MARK ! EXCLAMATION MARK: All end punctuation have the same value, a solid stop that indicates and end of information that is grouped into one grammatical unit of a sentence.

WHOLE REST = WHITE SPACE between paragraphs, too, is a form of punctuation, of this sense of breath. Although some may argue that this white space is along the lines of a fermata, this small piece of white space is only intended to allow the reader time to process the information already provided, and prepare for a new set of information. It is a signal that the story/information is changing from the course that has been previously established.

FERMATA = PAGE BREAK: Like the white space between paragraphs, the page break is an even greater pause, an indefinite pause, but for silence. Most often we find this break between chapters in many books. This space gives the reader the necessary infinite time to process the information that has been ingested, allowing sufficient time to prepare for the next chunk of information.

. . . ELLIPSES: Do not use unless you are removing information from an essay. There is no pause involved with the ellipsis, because it does not represent any type of spoken variations, it is only a means to visually tell the reader that something has been taken out of the information provided.

I do not include hyphens, quotation marks, apostrophes, and asterisks because these are functions of grammar only, and do not suggest any change in rhythm, but exist to show the reader when information given is changing forms.

This is punctuation to the creative writer. Punctuation is more than grammar, it is a means by which we attempt to represent how we slow and speed up time when we speak. Once you consider punctuation in this manner, it makes for a completely different writing experience, and often makes for more unique and intriguing pieces of writing. Plus, you don’t have to memorize all those arbitrary rules.

Published on September 12, 2014 11:31

August 10, 2014

An Open Letter to Lunacy and Publishing

Dear Amazon (KDP),

Here's the thing. When it comes right down to it, as a corporation, you want money. In order for your organization to survive, individuals must buy product. And in order to move product, you must sell at the lowest price possible that still allows you to attain the greatest revenue (something to do with supply and demand I assume).

Now, I'm no economist, not by any means, but I do know this: you are not trying to take care of your readers as you so valiantly proclaim. Nor are you taking care of the authors who are creating content and publishing on your site. That is ridiculous. No organization the size of Amazon cares for its customers more than itself. That's just business. If any business took more thought for the customer and less for itself, that business would fail, in realizing that the products it created were unnecessary and only adding to the vile disease we call consumerism. We would have to be self-aware of the devastating consequence of its very existence. And we all know that would cause the entire structure of America to disintegrate, and nobody wants that now do they?

So, to put it simply: Amazon, as much as I love the ease of ordering whatever the hell I want from your site, you are not helping book culture in any way.

As a reader, how does Abraham Lincoln: Presidential F*ck Machine, Taken by the T-Rex, and Touched by a Demon further literary culture? That is not to say that the authors of these texts do not have the right to create such atrocities: because they do. And rightfully so. But these texts, amid thousands (perhaps millions) of others just the same make up a large portion of Amazon's list of e-books. Are these your support for furthering literary culture? Poorly written pornography? These are consumable products that do not require readers to experience something outside of themselves. They seek only to please, arouse, sensationalize, and devalue the beauty of language. They offer nothing to the reader but immediate gratification that disappears at book's end. That is not the purpose of art (or the sciences for that matter). Literature, art in general, and science, are meant to linger in the minds of its participants. Objects of creation are meant to be experienced, not consumed. They are meant to stir our consciousness into new thoughts, causing us to question our beliefs, our hopes, our dreams, our perceptions of reality. Literature is supposed to help us better understand human emotion. It is supposed to help foster empathy. Where is empathy in President Lincoln having sex with random women? There is none.

So, in response to ReadersUnite, I say this: hell no, Amazon. Hell. No.

P.S. E-books are the same as paperbacks in WWII? Really?

* * *

Dear Hachette,

I love books. Good books. Books that make me think about my surroundings in ways I had not previously considered. Books that change me forever. It's why I started writing. I wanted to change people. I wanted to show people a piece of the world they may not have experienced, or thought about, or even knew existed. But here's the thing: no one will publish my work. At least not my books. I have had in the last few years about 30 short fiction pieces published. Nothing much, but for an emerging author, it's a good start. I believe wholeheartedly that my fiction is attempting to further literary culture. As do many others. And I know many writers who deserve national and global attention for their formulated beauty. However, my problem begins with companies like you, Hachette. With publishers. Publishers who claim to want to further literary culture and beauty and knowledge, whatever the mantra, and yet are only concerned with money. In the end, publishers are corporations, large entities existing for the purpose of accumulating vast amounts of money (no different than Amazon). That's the new American Dream, apparently. That idea is the exact opposite of literary culture. It is that mentality that has gotten the world to where it is now in 2014. To a place where consumption outweighs necessity. To a place where quality is snubbed for quantity. To a place that reduces art and its creators to "pretty pieces of wasted time." This is bullshit.

I want to be on your side of this, Hachette, I really do. To fight for the author and keep us eating and paid. Except, I don't get paid. But that's beside the point. I can't be on your side, because you are not on my side. No publisher is. That is the true problem. That is what needs to be addressed here.

So, to answer that petition those 909 authors signed: I hope this all falls to pieces

* * *

Dear Authors,

How you doing? Well, I hope. Here's the thing: places like Amazon and Hachette (and all those other corporations wearing the facade of publishers), they don't care about you or your writing or your readers. They never have. It's not in their best interest to care. They are only capable of caring about themselves. It's the nature of the beast. The business must be fed or it will devour itself and there will be nothing left for the peons to eat. Welcome to 2014.

Now, I don't claim to have the answer to any of this. And, to be fair, I probably don't understand even 1% of what is really going on here. I know it's big. I know it's important. I know it could very well change the face of publishing and books as we know them. What I do know is this: we, the unrepresented authors, the over-looked, the ignored, the struggling, we are the victims here in a corporate pissing match. We are being used as fodder for either side's argument in attempt to prove something about publishing and fair wages and a whole list of nonsense I can't seem to follow. I never understand economics.

But my fear is that nothing is going to change for the good. At least not for us. Because none of us are actually being called into the fight. None of us are actually standing up against these companies. We are watching, picking sides, and hoping for the best. Signing petitions on either side won't make a difference. Crying at Amazon for being mean, or telling Hachette they need to suck it, isn't going to help. Emails don't make a difference, they just create more work for these corporations that then makes them angry at each other, and at us, and that will only increase the possibility for explosions. As simply as I can put it, both companies at their cores are evil. Not in the "worshiping Satan and sacrificing virgins over fires" sense of the word, but in the "I'll destroy anyone and anything that gets in my way so I can be better than you" sense of the word.

We are writers. We are creators of beauty, of sorrow, of life; we are empathizers. It is our responsibility (although self-imposed) to expose the world to itself. To tear open reality and examine its nucleus to find out what really makes real real.

The answer is simple, but perhaps not easy. At least it's simple for me. And goes like this:

We, the writers of the world, will no longer be slave to the publisher. We will no longer define our success by the systems of measure we did not help to create. We will no longer support the bank accounts of illiterate business men and women deciding the future of literary culture. We will no longer allow our precious words to be abused by incompetent office workers pushing piles of paper between desks. We will no longer submit our work to publishing house conglomerates. We will no longer waste our time on this idiocracy.

We will no longer publish our work through any means save our own.

To hell with this world. To hell with society. To hell with corporations. And to tell hell with consumerism.

To hell with you Amazon. To hell with you Hachette. To hell with publishing.

Here's the thing. When it comes right down to it, as a corporation, you want money. In order for your organization to survive, individuals must buy product. And in order to move product, you must sell at the lowest price possible that still allows you to attain the greatest revenue (something to do with supply and demand I assume).

Now, I'm no economist, not by any means, but I do know this: you are not trying to take care of your readers as you so valiantly proclaim. Nor are you taking care of the authors who are creating content and publishing on your site. That is ridiculous. No organization the size of Amazon cares for its customers more than itself. That's just business. If any business took more thought for the customer and less for itself, that business would fail, in realizing that the products it created were unnecessary and only adding to the vile disease we call consumerism. We would have to be self-aware of the devastating consequence of its very existence. And we all know that would cause the entire structure of America to disintegrate, and nobody wants that now do they?

So, to put it simply: Amazon, as much as I love the ease of ordering whatever the hell I want from your site, you are not helping book culture in any way.

As a reader, how does Abraham Lincoln: Presidential F*ck Machine, Taken by the T-Rex, and Touched by a Demon further literary culture? That is not to say that the authors of these texts do not have the right to create such atrocities: because they do. And rightfully so. But these texts, amid thousands (perhaps millions) of others just the same make up a large portion of Amazon's list of e-books. Are these your support for furthering literary culture? Poorly written pornography? These are consumable products that do not require readers to experience something outside of themselves. They seek only to please, arouse, sensationalize, and devalue the beauty of language. They offer nothing to the reader but immediate gratification that disappears at book's end. That is not the purpose of art (or the sciences for that matter). Literature, art in general, and science, are meant to linger in the minds of its participants. Objects of creation are meant to be experienced, not consumed. They are meant to stir our consciousness into new thoughts, causing us to question our beliefs, our hopes, our dreams, our perceptions of reality. Literature is supposed to help us better understand human emotion. It is supposed to help foster empathy. Where is empathy in President Lincoln having sex with random women? There is none.

So, in response to ReadersUnite, I say this: hell no, Amazon. Hell. No.

P.S. E-books are the same as paperbacks in WWII? Really?

* * *

Dear Hachette,

I love books. Good books. Books that make me think about my surroundings in ways I had not previously considered. Books that change me forever. It's why I started writing. I wanted to change people. I wanted to show people a piece of the world they may not have experienced, or thought about, or even knew existed. But here's the thing: no one will publish my work. At least not my books. I have had in the last few years about 30 short fiction pieces published. Nothing much, but for an emerging author, it's a good start. I believe wholeheartedly that my fiction is attempting to further literary culture. As do many others. And I know many writers who deserve national and global attention for their formulated beauty. However, my problem begins with companies like you, Hachette. With publishers. Publishers who claim to want to further literary culture and beauty and knowledge, whatever the mantra, and yet are only concerned with money. In the end, publishers are corporations, large entities existing for the purpose of accumulating vast amounts of money (no different than Amazon). That's the new American Dream, apparently. That idea is the exact opposite of literary culture. It is that mentality that has gotten the world to where it is now in 2014. To a place where consumption outweighs necessity. To a place where quality is snubbed for quantity. To a place that reduces art and its creators to "pretty pieces of wasted time." This is bullshit.

I want to be on your side of this, Hachette, I really do. To fight for the author and keep us eating and paid. Except, I don't get paid. But that's beside the point. I can't be on your side, because you are not on my side. No publisher is. That is the true problem. That is what needs to be addressed here.

So, to answer that petition those 909 authors signed: I hope this all falls to pieces

* * *

Dear Authors,

How you doing? Well, I hope. Here's the thing: places like Amazon and Hachette (and all those other corporations wearing the facade of publishers), they don't care about you or your writing or your readers. They never have. It's not in their best interest to care. They are only capable of caring about themselves. It's the nature of the beast. The business must be fed or it will devour itself and there will be nothing left for the peons to eat. Welcome to 2014.

Now, I don't claim to have the answer to any of this. And, to be fair, I probably don't understand even 1% of what is really going on here. I know it's big. I know it's important. I know it could very well change the face of publishing and books as we know them. What I do know is this: we, the unrepresented authors, the over-looked, the ignored, the struggling, we are the victims here in a corporate pissing match. We are being used as fodder for either side's argument in attempt to prove something about publishing and fair wages and a whole list of nonsense I can't seem to follow. I never understand economics.

But my fear is that nothing is going to change for the good. At least not for us. Because none of us are actually being called into the fight. None of us are actually standing up against these companies. We are watching, picking sides, and hoping for the best. Signing petitions on either side won't make a difference. Crying at Amazon for being mean, or telling Hachette they need to suck it, isn't going to help. Emails don't make a difference, they just create more work for these corporations that then makes them angry at each other, and at us, and that will only increase the possibility for explosions. As simply as I can put it, both companies at their cores are evil. Not in the "worshiping Satan and sacrificing virgins over fires" sense of the word, but in the "I'll destroy anyone and anything that gets in my way so I can be better than you" sense of the word.

We are writers. We are creators of beauty, of sorrow, of life; we are empathizers. It is our responsibility (although self-imposed) to expose the world to itself. To tear open reality and examine its nucleus to find out what really makes real real.

The answer is simple, but perhaps not easy. At least it's simple for me. And goes like this:

We, the writers of the world, will no longer be slave to the publisher. We will no longer define our success by the systems of measure we did not help to create. We will no longer support the bank accounts of illiterate business men and women deciding the future of literary culture. We will no longer allow our precious words to be abused by incompetent office workers pushing piles of paper between desks. We will no longer submit our work to publishing house conglomerates. We will no longer waste our time on this idiocracy.

We will no longer publish our work through any means save our own.

To hell with this world. To hell with society. To hell with corporations. And to tell hell with consumerism.

To hell with you Amazon. To hell with you Hachette. To hell with publishing.

Published on August 10, 2014 10:01

June 6, 2014

The Fault in Our Living

I want to be part of something.

I have this thought often. How I want my life to mean something more than my life. That I want my existence to matter and affect other existences outside my immediate vicinity.

The problem is, it doesn't. And it won't. No one's does.

The Wife and I just got back from watching The Fault in Our Stars, the movie adaptation of one of our favorite John Green novels of the same namesake. I won't go into detailed movie review mode, but suffice it to say that it was one of the best movie adaptations of a book I, or my Wife, have ever seen. She cried more times than I imagined possible (the question should be asked "How many times didn't you cry?"), and even I welled up a few times. It was beautiful and emotional and symbolic and powerful and all those adjectives that the movie (and book) deserves. And, of course, as is the way of John Green, it was hilarious while dealing with heavy real-world complications that we often choose to ignore.

To the point: Augustus Waters talks a lot about oblivion and the desire to be remembered. To be special, to leave a mark on the world. A lasting mark. A feeling, I believe, many in the world have, though hide the fact. Hazel Grace Lancaster, on the other hand, points out that the world and humanity had a birth, and so shall it have a death. Whether in a day or millions of years, everything we know and love and remember will be obliterated, and not even humanity will be around to remember itself.

Or you.

I am like Augustus. I want to be remembered. I want to be part of something. Not just any something, but a great something, a something that will engrave my name into memories. More than just my memory, or my family's or my friends'. They will remember me, even if they don't want to, because that is how life works. We remember those we give time to and who give time to us. I don't want only that, I want more. I want infinite memories. A collective consciousness that infinitely recalls my existence into being at all hours of the day, across the globe. I want the memory of me to never sleep, to never hide in the shadow of the moon while in the light I am forgotten to billions of inane distractions.

I don't really know what I'm trying to say, I just have this urge to write, here. Maybe this is my attempt. To be remembered. Just these simple characters uploaded into that presumably greatest infinite of all, into that void of words and images and videos all awaiting random strangers' comments, to make the creator (me) feel important and alive. And real.

I don't know. Maybe it's a tiny cry for help, for a hand to reach out and clasp my shoulder, for that person to say "You matter to me, more than most, and without you, the world wouldn't be the world I know and love. You make living worth living, and for that I am grateful."

Perhaps.

I don't know. Perhaps it would be only a gesture, and though filled with love and truth and honesty, it would only sound like words, and nothing more. All I know is that I am not Augustus Waters, nor will I ever be him. Nor will anyone, because he isn't real. Or, I suppose, he isn't tangible, because what is 'real' anyway? I will never be remembered the way I want to be remembered. I can shout into the void and wait for a response for an eternity, but no one will answer. No one ever does, because no one is there. We are infinitely alone as we trudge through this mortal life. Some die too soon, some live too long. Most just are, and then die, and we move along. All we can do is be and try and love. Give love to those few who happen to stand right in front of us. Hold them, tell them we bottled the stars for them and hand them a glass of Champagne (or Sparkling Cider); tell them how even though we only have these brief moments together, between each moment is an infinity that we can never escape, that we don't want to escape, and that it is these brief passings between bodies that make us and our names matter, and exist, and last beyond our lives. And when we do, we can look into each others eyes and say:"Okay?" And you can smile and kiss and hug and touch and say:"Okay."

I have this thought often. How I want my life to mean something more than my life. That I want my existence to matter and affect other existences outside my immediate vicinity.

The problem is, it doesn't. And it won't. No one's does.

The Wife and I just got back from watching The Fault in Our Stars, the movie adaptation of one of our favorite John Green novels of the same namesake. I won't go into detailed movie review mode, but suffice it to say that it was one of the best movie adaptations of a book I, or my Wife, have ever seen. She cried more times than I imagined possible (the question should be asked "How many times didn't you cry?"), and even I welled up a few times. It was beautiful and emotional and symbolic and powerful and all those adjectives that the movie (and book) deserves. And, of course, as is the way of John Green, it was hilarious while dealing with heavy real-world complications that we often choose to ignore.

To the point: Augustus Waters talks a lot about oblivion and the desire to be remembered. To be special, to leave a mark on the world. A lasting mark. A feeling, I believe, many in the world have, though hide the fact. Hazel Grace Lancaster, on the other hand, points out that the world and humanity had a birth, and so shall it have a death. Whether in a day or millions of years, everything we know and love and remember will be obliterated, and not even humanity will be around to remember itself.

Or you.

I am like Augustus. I want to be remembered. I want to be part of something. Not just any something, but a great something, a something that will engrave my name into memories. More than just my memory, or my family's or my friends'. They will remember me, even if they don't want to, because that is how life works. We remember those we give time to and who give time to us. I don't want only that, I want more. I want infinite memories. A collective consciousness that infinitely recalls my existence into being at all hours of the day, across the globe. I want the memory of me to never sleep, to never hide in the shadow of the moon while in the light I am forgotten to billions of inane distractions.

I don't really know what I'm trying to say, I just have this urge to write, here. Maybe this is my attempt. To be remembered. Just these simple characters uploaded into that presumably greatest infinite of all, into that void of words and images and videos all awaiting random strangers' comments, to make the creator (me) feel important and alive. And real.

I don't know. Maybe it's a tiny cry for help, for a hand to reach out and clasp my shoulder, for that person to say "You matter to me, more than most, and without you, the world wouldn't be the world I know and love. You make living worth living, and for that I am grateful."

Perhaps.

I don't know. Perhaps it would be only a gesture, and though filled with love and truth and honesty, it would only sound like words, and nothing more. All I know is that I am not Augustus Waters, nor will I ever be him. Nor will anyone, because he isn't real. Or, I suppose, he isn't tangible, because what is 'real' anyway? I will never be remembered the way I want to be remembered. I can shout into the void and wait for a response for an eternity, but no one will answer. No one ever does, because no one is there. We are infinitely alone as we trudge through this mortal life. Some die too soon, some live too long. Most just are, and then die, and we move along. All we can do is be and try and love. Give love to those few who happen to stand right in front of us. Hold them, tell them we bottled the stars for them and hand them a glass of Champagne (or Sparkling Cider); tell them how even though we only have these brief moments together, between each moment is an infinity that we can never escape, that we don't want to escape, and that it is these brief passings between bodies that make us and our names matter, and exist, and last beyond our lives. And when we do, we can look into each others eyes and say:"Okay?" And you can smile and kiss and hug and touch and say:"Okay."

Published on June 06, 2014 23:22

May 29, 2014

Day 734

Just past the two year mark graduating with a Master’s degree in Creative Writing. Let’s see how things are going:-Unemployed: check-Living with parents: check-Reproducing with no viable and immediate means to take care of new family (now consisting of two children): check-Writing at a minimal pace and not completing any stories: check-Still waiting to publish a book: check-Friends doing better than I am (financially): check-Not using degree that took many years and lots of money to get: check

Sounds like the last two years have been quite the positive adventure for me and my family.

Now, I know I usually focus on the dismal aspects of living, because it’s easy and I find it more interesting to write about. However, even though these last two years have been extremely difficult and frustrating, there has been some good since graduating (I think) in the last six months or so:-The wife and I have finally given ourselves the time to work on our Etsy store, which is awesome I might add-We have two children, The Chubbs and Little Sir who are healthy and so far, well behaved-Without putting any effort into it at all, our photography business still brings in a little cash now and then-Finally I am part of a writing group that meets often, gets work done, and wants to do amazing projects, which encourages me to write more and do more and be more-First issue of From Sac went well, and we are currently working on the second issue, and we have great stories that we are publishing (still accepting more if you haven’t submitted)

Those are just a few parts of my life that are starting to go well, even though I tend to not see them. Because the last two years have been hard. Not just hard work, which is good, hard work makes you strong, makes you better, makes you beastly; but hard in the sense that even with all the hard work, it just hasn’t really worked out most of the time. The teaching job that I kind of had ended six months before it was supposed. The 20 some odd teaching job applications I’ve sent out have all turned up fruitless (not counting the other dozens and dozens of job applications that I’ve sent out for other non-degree related jobs). Publishing has been almost at a standstill for the past eight months. Rejection after rejection, and for a few contests that I thought for certain I had a chance at least getting third place in. And all this happening under the scrutinizing eyes of my parents, who watch every parenting choice, every marital choice, every personal choice that I make, critiquing, offering unsolicited advice, and yet unable to understand why I get frustrated.

Now, I know there are some out there who would say: “Well, why didn’t you major in engineering, or business, or science?” “You should be grateful you have a family that helps you.” “Just because you have a Master’s doesn’t mean you’re entitled to anything, and you should just work anywhere doing anything,” etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. But here’s the thing: I didn’t major in engineering or business or science, I majored in Creative Writing; I am grateful for the help of my parents, but does that mean they won’t drive me crazy?; I was told by my parents and society that if I went to college and got a degree, I would be guaranteed a job after graduating, especially with a Master’s, and yet there are no jobs; I have a family to take care of, and not just any job can take care of them, it won’t be enough to put food in their mouths and shelter over their heads (even crappy food and rundown housing).

Life now is hard. For everyone. I suppose it’s always been hard. Since the dawning of time humans have struggled. That’s great, good for them. Go humans of the past. I’m not them. All I know is now. My life. And it’s difficult. For me. Maybe not for someone else, or you, but for me, these last two years have been . . . devastating. As a person I have never had the greatest self-esteem. Call it personality, genetics, societal pressures, religious self-loathing, whatever. Sine a child, I have not really liked myself, or expected anything good to happen in my life. But overall, through elementary school and high school, and even college, I had an okay time. In these last two years, though, I have never felt lower, never been more sick to see my face staring back at me in the mirror. To know that face is nothing. A nobody. A flesh sack drifting through life as over seven billion other flesh sacks try to figure out what it means to live, and most never really seeing anything beside the backs of people’s heads as they queue up for the slaughter house. There are the few who become what they want to be: some idols for the lost and hopeless, others recluses and despisers of the animals human beings really are, others sheep caught in the hustle and bustle of trying to figure things out and they are trapped moving the wrong direction but they can’t see anything except what’s right in front of them and since they are moving they think it must be forward until they are falling off the cliff into oblivion and it’s too late to change course. Others, they pretend none of this exist, reality, humanity, time, space, the whole experience is just a dream, a time between times where consciousness has grown into some uncontrollable malice pretending at some philosophical evaluation we have titled “Life”. Others drink until all they feel nothing. Or do drugs. Or whatever.

Me? I just want to be an artist. I want to write and publish. I want to make beauty with my hands. I want to be happy with my wife and children. I want to feel good about what I do with my time and the people I spend giving my time to. I want to live. Without voices. Without 1984 growing ever stronger. Without the worry of being. It’s not a lot. I don’t need to be rich (but I would take it if it was offered), I don’t need to be famous (although that would be awesome, I think), I don’t need fancy cars (I hate cars), or a big house (I plan on building my own mini house some day). I don’t need the worldly commodities I’m told I should want. I just want a few acres with trees and meadows and streams, a tiny house with laughing children and a beautiful wife and no TV, where we can just do what we want when we want to do it. It’s not a lot, but it’s what I want.

Published on May 29, 2014 23:14

April 16, 2014

I teach my students to come up with good titles for thei...

I teach my students to come up with good titles for their essays. Because titles are important for essays. It’s the first thing a reader sees associated with an essay. A one sentence summary that somehow is supposed to capture the essence of the writing, while drawing the reader to conjectures about whatever topic populates the page. I teach them when doing research, before reading an article, read the title first, make sure it sounds like it is going to focus on the essay’s topic. I teach them to make their titles complex and long, something catchy, and explanatory. Like “Which Witch is Wich?: Commonly Misused Words and Their Homophones”, or whatever. It’s fun and precise. The only problem is: I hate titles. Well, hate is vague and negative word I’m told, so I’ll be more specific. I loathe them. I detest them. There is nothing more troublesome than a title, especially a misplaced, ambiguous, misleading title. They are evil, deformed spawns of highfalutin pedagogues.

Whoa. Let me explain.

When an author titles writing, specifically creative writing (because creative writing such as fiction, non-fiction, poetry, screenplays, etc., mystery is part of the appeal), we need the unknown. The unknowable. Yes, someone does the writing. And yes, they have some ‘control’ over the final product. However, ask any writer, a true writer, a lover of the craft, and they will tell you that writing is a process of discovery, not creation. A writer (and all forms of artists should be included here) does not compose from nothing, a writer is part of a whole world of language, of experience, of knowing and unknowing and searching. Each word, sentence, paragraph; each character, scene, story; each poem, song, book, they are all accidents of discovery. They are stories that are found, not made.

I had a film teacher once describe the artistic process as a person trying to find some great unattainable entity, something we all are searching for. I think of it like this:

There is this thing we call Art, out there somewhere, no one knows where. Perhaps it’s the Ethers. It’s always there, existing, infinite, omniscient, omnipresent. Some people call it God. Some call it Karma. Others Buddha or Allah. Others, the great perhaps. Other still think of it as Science, as those perfect yet-undiscovered laws that completely govern the Universe. The theory of everything. But it doesn’t matter the name, because it’s always there, waiting. Waiting for someone to reach out and touch it, to grab a piece of it and examine, dissect, and reassemble its parts. We never have our own ideas, not really. They are all out there with Art, in Art, and we are participators within Art. As artists, we must put ourselves in a place where we become in tune with this ephemeral Art. We meditate. We exercise. We practice. We study other artists’ experiences with Art. We read and write and create, over and over, until we are in a place where we can almost see Art, almost smell and taste it, where we feel its presence in us, flowing through our veins. We suddenly call it ‘inspiration’, that elusive light flickering Morris Code in the dark across the infinite ocean of doubt and hesitation and worry. And when we feel it, then we have captured it (but really, it is a gift given to us), and we begin to create.

That is writing. That is how a writer finds story, character, beauty, and truth.

This is where my loathing of titles comes from. It is difficult enough to align yourself with Art for a brief moment while through you it generates something magnificent. It is a whole other scenario to name that new creature. I have three reasons why:1) You cannot give a name to something that isn’t truly yours.2) You cannot name something that you do not fully understand. Each piece of writing is an exploration, and all the parts that can be discovered cannot all be seen by one person. Something will always go unseen.3) Naming a piece of writing drastically reduces the mystery of the piece, ruining the reader’s ability to formulate their own interpretation, to have their own unique and unadulterated experience.

Number three is the most important to me. I don’t like guiding readers to any sort of conclusion with my writing, especially with it involves stories--fiction and non-fiction alike. Titles are huge guiding influences (there are others, but that will be for another time). They give a reader too big of a hint at the story, whether it’s the actual purpose of the piece, or simply a glimpse at one of the characters. Titles ruin the reading experience.

As artists and viewers, hell, just people, we all come with a lot of baggage. A lot. Millions of tons of it. We have so many filters that cloud our ability to communicate, interact, interpret, and display our emotions, that it’s no wonder we can’t get along. All the more reason to avoid titles. It’s difficult enough to try and understand another individuals experience with Art, adding a title to that only disrupts an already improbably connection.

I take it further than just dislike for a title. I distain having any identifying information associated with my writing: title, author’s name, date, publication/copyright info, the name of the author and title of the book on each and every page reminding you who ‘created’ this piece of work and what you should ‘call’ it as if you would have forgotten part way through what you were holding; I want none of it. Even page numbers. That information distracts from the text. It tells the reader that this experience is fabricated, only pretend, what you now embrace is merely a commodity to be added to the pile collecting in your garage or attic or closet. To be used and discarded without further thought.

That mentality terrifies me.

That mentality leads to eBooks and tablets and the loss of touch, of the physical experience.

But titling doesn’t just stop at Art. We title everything, give everything a name. Our cars, our homes, our computers; email accounts, Facebook, Twitter, Instragram, YouTube; most important, we name each other. Chubbs the Second was born a few weeks ago, and we gave him a name. I say ‘gave’, because it was a gift, some hope that he will take his name and create a story that flows from his title. A title that I and the Wife hope he will grow into, that will become the epigraph to his life, the title of him. We named him without knowing him. Only born for an hour and we named him, a name we had in mind for years but waited to finalize until we saw his face, a name that will come to define every single action, good or ill. A name he will have to live up to, because we forced it upon him (gifts are like that sometimes). True, if he chooses, he could change it in the future. But that won’t change the effect it will have had on his growing years; or the years to come, knowing that he altered his title to fit the story he now wants to tell, that he wants to forget the story already written but cannot change.

Titles are complicated, at best.

Sometimes we aren’t even happy with the titles others are given--our friends--at birth, or our own titles for that matter, and so we create new ones, as if we can rename our/their story, alter the course that has already been traveled, become what we/they are not but imagine ourselves/them to be.

Unfortunately, there is an ancient established pedagogythat determines the structures of which we are a part, which dictates our roles in civilized society. A Panopticon, if you will. If I want to live in society, I have to have a name, which translates into a social security number that allows me to be monitored (mostly on a financial level). I need to have a birth certificate that indicates I exist, that my specific title is attached to my blood, that I am who I am. Those two documents then push me (or us) in various directions that only exist because of that title, of our documented existence, which we further propagate through societal dialogues. We don’t introduce ourselves by personality, by interest, by desire, but by our title. By those few defining syllables that from birth form our identity. And, when it comes down to it, if we want to create, to collaborate with Art, we must title that interaction, stamping our name to it to make it ‘real’, to make it exist.

I know I can’t escape this system rooted in place for millennia, but I want to. I want to burn the whole artifice down and start anew. I want to be the trillions of atoms intelligently bonded structuring my body. I want others to be their bodies, their own beings without titles, without misnomers. I want to just exist because I am, because we all are.

Is that too much to ask?

Published on April 16, 2014 17:18

What's in a Name?