Gordon G. Chang's Blog, page 12

March 10, 2015

Is China’s One-Party State on the Brink?

“We cannot predict when Chinese communism will collapse,” writes David Shambaugh in an essay in Saturday’s Wall Street Journal, “but it is hard not to conclude that we are witnessing its final phase.”

The George Washington University professor is known in the global China-watching community as having close ties to the Communist Party of China. In his essay, titled “The Coming Chinese Crackup,” he mentions attending a conference at the Central Party School in Beijing last December and having other contacts with cadres and officials. He was recently named one of America’s top 20 China watchers by China Foreign Affairs University, which is affiliated with China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Shambaugh’s turnaround—he is well known for writings suggesting China’s one-party state is stable—has caught the attention of the world’s China watchers. Listserves devoted to that country are discussing little else, and he has apparently angered Beijing. Global Times, the nationalist paper controlled by People’s Daily, issued a strident piece rebutting Shambaugh on Monday.

Why does Shambaugh believe we are witnessing the “endgame of Chinese communist rule”? He refers to five “telling indications of the regime’s vulnerability and the party’s systemic weaknesses.” Included in the list are fleeing elites, intensified political repression, lack of cadre enthusiasm, and a quickly deteriorating economy.

And then there is venality. Not long ago, political scientists and others thought China’s Communist Party was sturdy and even believed its obvious maladies actually constituted strengths. For instance, many, especially in the academic community, argued its endemic corruption helped keep the political system together, giving officials a direct financial stake in supporting the continuation of the regime. Shambaugh’s essay, on the other hand, includes corruption as one of the fatal five flaws and highlights a new trend in thinking: It is an organization so crooked it cannot survive for long.

In recent days there has been a flurry of writing about the long-term prospects of the Chinese one-party state. Early last month, Pentagon adviser Michael Pillsbury released his book, The Hundred-Year Marathon, painting a picture of a durable dictatorship, but many of the other recent contributions portray the Chinese regime on its last legs. One appeared in the Journal, Michael Auslin’s “The Twilight of China’s Communist Party,” and another on the National Interest’s website, “Doomsday: Preparing for China’s Collapse,” by Peter Mattis of the Jamestown Foundation.

Some of Shambaugh’s fellow academics are getting in on the act as well. For instance, Chen Dingding of the University of Macau penned “Sorry, America: China Is NOT Going to Collapse,” a broad attack on the George Washington professor’s essay, also for the National Interest’s website.

China has always loomed large in the imagination, but now the country is beginning to look weak, not the “unstoppable juggernaut” that is supposed to dominate the world and own the century.

China’s communist system, even in the so-called reform era, seemed to defy principles of governance and economics observed around the world. Until now, however, the Chinese state has been fueled in large measure by confidence, both inside and outside its borders. Shambaugh’s essay tells us that many who have been watching—and cheering—the country’s ascent now see it at its end.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaCommunismEconomics

Asia PacificChinaCommunismEconomics

March 5, 2015

Will Russia Buckle, Sell China Control of Its Oil Fields?

On Friday, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich signaled that the Kremlin would be willing to give Chinese companies majority stakes in Russian oil and gas fields. “There used to be a psychological barrier,” he said, speaking from Krasnoyarsk, a city in energy-rich Siberia. “Now it doesn’t exist anymore. We are interested in maximum investments in new industries. China is an obvious investor for us.”

At present, Russia caps foreign ownership at 50 percent for oil fields where reserves exceed 70 million tons and gas fields containing more than 50 billion cubic meters in reserves. Yet that could change if the Chinese want bigger stakes. As Dvorkovich said, “If there is a request, we will consider it.”

Given his country’s economic woes, it doesn’t seem likely that the cash-strapped President Vladimir Putin is in a position to say “nyet.” Last year, Russia’s gross domestic product underperformed every estimate, growing, according to official sources by only 0.6 percent, down from 1.3 percent in 2013, 3.4 percent in 2012, and 4.2 percent in 2011. The slide, now three years long, signals structural problems.

On top of the structural problems, the Western sanctions imposed on Russia over the invasion of Ukraine, occurring while energy prices collapsed, caused a major disruption to the economy. Money hemorrhaged out of the country last year, when capital flight doubled to $151.5 billion. The ruble, the world’s second-worst performing currency in 2014, fell 42.0 percent against the dollar, taking down the country’s foreign exchange reserves with it. Last year, the reserves fell from $510 billion to $380 billion, a drop of 25.5 percent.

This year looks even worse. Forecasts have progressively deteriorated. Once, Russian officials said GDP would grow 0.5 percent, but even that minimal rate looks unattainable now. Now, they are talking about the economy shrinking 3 percent, as Minister of Economic Development Alexei Ulyukayev said at the end of January. Others see even bigger declines. A Reuters poll of analysts predicts a 4.2 percent fall, and Moody’s is talking 5.5 percent. Anders Aslund of the Peterson Institute for International Economics predicts the drop could be as much as 10 percent.

Russia’s meltdown seems the perfect setup for China to ride to the rescue. “Putin is currently in a tough situation,” said a “senior Chinese oil industry official” to the Moscow Times. “We all know this. One of the ways to help him get out of the mess is trying to improve ties with China.” Not only has Beijing, through state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation, agreed to buy large quantities of oil and gas from Russia, it has extended assistance.

In October, for instance, China and Russia signed a $24.4 billion currency swap arrangement, effectively providing Russia liquidity, and the agreement might be expanded, as Chinese Commerce Minister Gao Hucheng has suggested.

Moreover, in late December the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, permitted the trading of renminbi-ruble derivatives to facilitate commerce between the two countries. Perhaps the most dramatic sign of the degree to which Beijing is propping up the Kremlin is that China’s Export-Import Bank extended credit to two sanctioned Russian banks, relieving pressure from the measures.

And we can expect additional links between the two economies. Li Jianmin of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences said in December that Beijing could do more by funneling additional assistance to Russia through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or the BRICS forum.

China and Russia are molding their economies together. Total trade volume between the pair increased 6.8 percent to $95.3 billion last year, a record. Putin sees trade with China hitting $200 billion in 2020.

Even if trade does not reach such a lofty level, the integration of the two economies is accelerating, most notably in the oil and gas sectors, which account for a disproportionate share of the trade volume. If the Kremlin allows a Chinese company to take a majority stake in a Russian energy field, as Dvorkovich indicates, the long-talked-about Dragon-Bear Axis cannot be far off.

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaRussiaChinaUSVladimir Putin

Europe and Central AsiaRussiaChinaUSVladimir Putin

February 25, 2015

Re-monopolizing China's Industry

The recent completion of two government-directed mergers in China’s energy and manufacturing sectors and other mergers now in the making suggest Beijing is reversing two decades of reform intended to make Chinese industry more efficient and competitive in local and global markets. The ongoing effort is certain to fail in the long term.

As reported by the Wall Street Journal last week, Beijing is contemplating two mergers of state oil giants: the China National Petroleum Corporation with China Petrochemical Corporation, better known as Sinopec,and China National Offshore Oil Corporation with Sinochem Group. The apparent goal is to increase China’s leverage in the global energy market. “We want to create a big Chinese brand to better compete overseas,”an informed official told the paper. He added, “We want our own ExxonMobil,” failing to note that these Chinese giants are already larger than ExxonMobil by various measures, including, most importantly, the size of balance sheet.

One or both combinations, if consummated, will come on the heels of other government-compelled mergers. One, announced last December, resulted in the consolidation of CSR Corporation and China CNR, the world’s biggest makers of trains. Ironically, these two companies were spin-offs from the same parent, the China National Railway Locomotive and Rolling Stock Industry Corporation. Xie Jilong, CNR’s board secretary, at the time stated the combination was initiated by Beijing, not the two firms.

Why the merger? The State Council, the cabinet of China’s central government, was upset that the two Chinese manufacturers competed against each other for the right to build 284 subway cars for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, in Boston. CNR won the competition last October with a bid that was about half of the highest bid and a quarter lower than the second-lowest bid, according to Lawrence Li of the banking firm UOB Kay Hian, speaking to the South China Morning Post.

Soon after the CSR-CNR merger, the China Power Investment Corporation was similarly forced to merge with the State Nuclear Power Technology Corporation. Additional deals in the state nuclear sector are expected, especially an amalgamation of China National Nuclear Corporation and China General Nuclear.

In the near term, Beijing may be able to prevent state companies from bidding against each other in foreign markets, but in the long term China loses. These mergers will create the very problems that the reforms launched 20 years ago were intended to eliminate when state monopolies were broken up—inefficiency and higher prices brought on by political meddling, central state management, corruption, and patronage. Tellingly, local Chinese officials opposed the December deal between CSR and CNR, fearing that higher prices would result from the elimination of meaningful competition.

Apparently this has not occurred to Xi Jinping, China’s ruler since November 2012, who now holds sway over economic policymaking and almost certainly is behind these corporate consolidations. Referring to state enterprises last August, he reportedly said the government “must ensure they thrive.”

That’s what the Maoists thought when they created the gargantuan businesses and then protected and nurtured them. Since then, it has been obvious that the pro-monopoly policies of the 1950s crippled China’s economy and industry. That’s why Beijing technocrats spent the last two decades taking apart Mao’s monopolies.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaRising ChinaMonopoliesMaoist MonopoliesReform

Asia PacificChinaRising ChinaMonopoliesMaoist MonopoliesReform

February 19, 2015

Hong Kong Protests Traders from China

On Sunday, more than a hundred protesters—most of them young—mobbed New Town Plaza, a mall in the Sha Tin District of Hong Kong. There, they clashed with shoppers and hounded tourists from mainland China.

Police tussled with the demonstrators, wielded batons, used pepper spray, and made arrests during the second consecutive Sunday of demonstrations against “parallel traders,” individuals buying goods in Hong Kong and lugging them across the border to China. On February 8th, there were similar protests in Tuen Mun, an area also close to the China border.

For years, residents of Guangdong Province—from quick-buck artists to concerned parents—have entered Hong Kong, a special administrative region of China, and bought foodstuffs and household items to bring back to the mainland.

The trade eventually became a hot political issue. The last time I walked across the border from Hong Kong to China—in November 2013, at the Lo Wu crossing—Hong Kong Immigration was blaring warnings over loudspeakers about the smuggling of powder—not heroin or cocaine, but milk.

Foreign milk powder is valuable in the mainland because of the continuing series of scandals involving adulterated products. In 2008, for instance, an estimated 300,000 Chinese children suffered kidney damage and at least six infants died because local producers were lacing milk with melamine, an industrial chemical. Mainlanders bought so much powdered milk in Hong Kong that the transportation of more than 1.8 kilograms of it from the territory was made a criminal offense in 2013. On Sunday, marchers shouted, “Mainlanders go back to the mainland!” and “Drink your own milk powder!”

So why should free-spending tourists from the mainland spark outbursts of violence in Hong Kong? The mainlanders, after all, boost the local economy, spending an average of more than $1,000 per trip. And these days they make almost 50 million visits to Hong Kong each year.

But the influx—there were only several thousand visits in 2003—has clogged Hong Kong’s transportation infrastructure. Moreover, stores started catering to big-spending Chinese and shunned local residents. And then mainlanders—“locusts,” in Hong Kong parlance—started clearing off the shelves in supermarkets, driving up prices. Some parallel traders make multiple trips a day.

Why have tensions over parallel trading boiled over now? Observers hear political overtones. Most of the protesters during the last two Sundays were of student age, apparently veterans of the “Occupy” demonstrations that paralyzed portions of Hong Kong when tens of thousands of residents took over streets and plazas for 79 days starting in September, angry at Beijing’s plan to control elections for Hong Kong’s chief executive, the territory’s highest political official.

At the parallel trading protests this month, Hong Kong residents flew colonial-era flags, a symbol of defiance of Beijing. In Sha Tin, one of the flag-wavers was 13 years old.

“It’s been festering since Occupy,” said James Bang, a volunteer at the supply tents in last year’s demonstrations, referring to the sentiment propelling the parallel trading protests. “It is quite ugly.” As Bang explained, protesters “are not racist, horrible people but they feel like they’ve been ignored and trampled on and had their country taken away from them.” A Tuen Mun resident linked the February 8th demonstration in his neighborhood to the “Umbrella Revolution,” the name for last year’s protests, because in both “people became aware and start questioning.”

Some analysts say Beijing won in December because it was able to clear Hong Kong’s streets. That’s an incorrect interpretation. The pan-democrats are energized, more so than they have been in years, and the suppression of the Occupy movement has only increased their support in society.

Bai Xiaoyu, a researcher in the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, recently wrote of “radicalization” and “spontaneous movements” in Hong Kong. As people there speak of self-determination and independence from the Chinese regime Bai serves, there’s no need for written warnings. Chinese leaders can see for themselves that radicals are taking to the streets of Hong Kong and people there are telling Beijing to get out.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaHong KongTradeDemocracy

Asia PacificChinaHong KongTradeDemocracy

February 11, 2015

Will Japan Flex Its Naval Power in South China Sea?

In a startling interview with Reuters, Admiral Robert Thomas, commander of the US Seventh Fleet, said that America would welcome Japan patrolling the South China Sea, south of the Japanese islands and far beyond the country’s current area of operations. Tokyo has no current plans to send planes and ships into that body of water, but Beijing, which aggressively patrols there, is already upset.

“I think that JSDF operations in the South China Sea make sense in the future,” Thomas said, using the acronym for the Japan Self-Defense Forces. The admiral’s comment signaled Japan would soon take on responsibilities beyond its vicinity because Washington and Tokyo are now in discussions to revise bilateral security guidelines.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has been advocating an increased military role for his nation, which has been constrained by its so-called Peace Constitution. Article 9 of that document, which went into effect in 1947, does not permit the country to maintain “land, sea, and air forces” or even to defend itself in the event of attack—“the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation.” Abe would like to amend Article 9, but he and his predecessors have essentially written much of the provision out of existence through “interpretations.” Despite constitutional restrictions, Japan possesses one of the most capable militaries in East Asia.

Now, Abe has found an important backer for his expanding ambitions. “We would agree with Admiral Thomas that those kinds of patrols and activity is welcome and will help contribute to stability in the region,” said Admiral John Kirby, Pentagon press secretary, within hours of the release of the comments of the Seventh Fleet commander. “There’s no reason for China or any other nation to look at it any differently.”

Perhaps so, but Beijing was unconvinced by American assurances. “Countries outside the region should respect the endeavor of countries in the region to safeguard peace and stability, and refrain from sowing discord among other countries and creating tensions,” said Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying.

China’s academics were not so restrained. Shen Dingli of Fudan University, writing in People’s Daily, said that “some superpower outside the region” is “anxious to see the world in disorder.”

The most interesting response, however, came from Mark Valencia, an adjunct senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, in Hainan Province. Valencia, who almost invariably propagates Beijing-friendly themes, warns the move could be the “tipping point” for war and then states the region would not support increased Japanese activity. “If truly intended and implemented, this would be the most insensitive and provocative US/Japan move yet in Asia,” he writes on the Diplomat website. “Indeed, a regional military-related role for the former brutal, racist, still-feared and, for many, insufficiently repentant conqueror of China and Southeast Asia would set off alarm bells throughout the region.”

In fact, Japanese patrols would almost certainly be welcomed by others in the region. They certainly would be in the Philippines. At the end of last month, Philippine Defense Secretary Voltaire Tuvera Gazmin met Japan’s Defense Minister Gen Nakatani in Tokyo, where they signed a memo on cooperation contemplating military exchanges, training, and transfers of technology and equipment. “Common security concerns provide an opportunity to deepen defense cooperation,” Gazmin told his Japanese counterpart.

How about Vietnam? Hanoi and Tokyo expanded their military partnership in March. In August, Japan donated six vessels to Vietnam for maritime security.

Indonesia? At the beginning of this month, the Indonesian ambassador to Japan said Jakarta would soon sign a defense partnership with the Japanese.

And the region as a whole? At the end of May, Abe gave the keynote address at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, and he took the opportunity to introduce East Asia to the “new Japanese.” “These ‘new Japanese,’ ” he explained, “are Japanese who are determined ultimately to take on the peace, order, and stability of this region as their own responsibility.”

At the beginning of this decade, East Asians would have shuddered if anyone Japanese had spoken those words. Virtually no one in Tokyo would have uttered them.

There is one reason why Abe could get away with saying such things at a high-profile setting. Countries are now more concerned about the Chinese than Abe’s soldiers, sailors, and pilots. Beijing has done the seemingly impossible: make Japanese military involvement in the region not only acceptable but sought after.

So Valencia is wrong when he writes that “alarm bells” will ring when Japanese planes begin flying over the South China Sea.

The land of the rising sun, for better or worse, is about to return to the region.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaJapanUnited StatesNavyMaritime Disputes

Asia PacificChinaJapanUnited StatesNavyMaritime Disputes

February 9, 2015

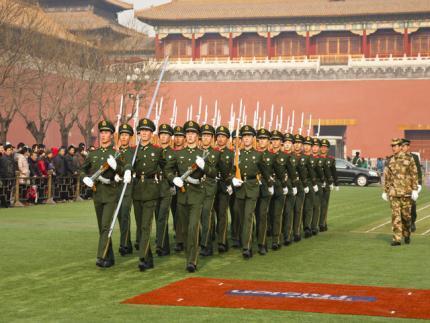

An Ominous Chinese Military Parade

Everyone loves a parade.

And, evidently, no one more so than General Secretary Xi Jinping. The Chinese ruler has scheduled a grand military procession through the heart of Beijing in early September. The news of the parade, carried in state and Communist Party media but still not officially confirmed, was unexpected and suggests China will continue to move in dangerous directions.

There have been 14 military parades in the history of the People’s Republic of China.

Eleven occurred between 1949 and 1959, during the era of founder and tyrant Mao Zedong. His first three successors—Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao—each presided over one military parade, all of them on October 1st, National Day.

The last such parade was in 2009, marking the 60th anniversary of the founding of New China, as the party calls the country. The one before that was in 1999. Most everyone, therefore, assumed the next military parade would be held on October 1, 2019.

This year’s parade, observers say, will commemorate the 70thanniversary of the end of World War II. Technically, it will, in all probability, be held on a holiday, marked for the first time last year and officially termed “Victory Day of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.” The choice of the day for the event has naturally raised concerns about Beijing’s militarism, as Japan has been a recent target of provocative Chinese acts, especially around the disputed Senkaku Islands, barren East China Sea outcroppings that Tokyo now administers.

Not surprisingly, China’s defenders have been working overtime to minimize the implications of the parade. “Authorities have been at pains to stress that the intention is to add to the global message of peace being sent by the various worldwide anniversary events, not to heighten tensions with Japan and its ally, the US,” the South China Morning Post noted in an editorial on Saturday. “They are right; Beijing has repeatedly told the world that China’s rise will be peaceful and that its military modernization is aimed purely at defending Chinese interests.”

If Xi truly wanted to send a “global message of peace,” as the Hong Kong paper assures us, he would release a million doves in Tiananmen Square and parade smiling children past the reviewing stand in September. The message conveyed by stoned-faced, goose-stepping soldiers, on the other hand, is chilling, as will be the sight of new fighters and missiles analysts expect to be on display. And unfortunately “defending Chinese interests” is not what most would consider “peaceful” if it means seizing parts of India, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, and South Korea; annexing Taiwan; or exercising virtual control of the international waters and airspace of the South China Sea.

Xi has been wasting no time in asserting China’s expansionist claims since he became the party’s general secretary in November 2012. Aggression has taken a time-out during the past few months—Beijing has been relatively quiet recently—but the planned parade nonetheless looks ominous.

Jin Zhong, a Hong Kong–based political observer who publishes Open Magazine, told the Los Angeles Times that the event “shows Xi has big ambitions” and that he “dares to do things only Mao Zedong could do.” Therefore, some believe the parade—“a bold stroke” by Xi, in the words of the Times article—is less about Japan and more about the leader’s internal status vis-à-vis his opponents. The celebration is all about showcasing Xi’s authority, they say.

If so, the question arises why he needs to break precedent to show off power. One explanation is that Xi is feeling insecure.

Such insecurity would not be consistent with the view of most observers that Xi is in command and that purges of civilian and military ranks and loyalty oaths from the top brass show he has consolidated control over the party’s apparatus. Yet the fact that purges have continued suggests the political situation in Beijing has not been settled. If it had been, there would be no need for more bloodletting. Similarly, the demand for continuing expressions of loyalty tells us that some elements are not considered loyal.

The majority view that Xi is in control of Beijing is premised on the notion that he has the support of the “princelings,” the offspring of high officials, past and present. Yet this term covers individuals spanning the political spectrum and is not a group like those that served as the political base for former leaders, like Jiang’s Shanghai Gang or Hu’s Communist Youth League.

Some analysts, like the veteran Willy Lam, even are beginning to argue that the military is becoming the core of Xi’s rule. If Lam is correct, it must mean the Chinese supremo is—or is becoming—beholden to flag officers and is particularly dependent on their backing. In this case, the September parade may be a sign of military assertion, rather than, as most everyone assumes, a sign of Xi’s domination of the military.

In any event, the country is now breaking tradition to show off its most fearsome instruments of war, and that is undoubtedly a worrying signal, whatever the state of politics in the Chinese capital.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaXi JinpingCommunismCommunist Party

Asia PacificChinaXi JinpingCommunismCommunist Party

January 28, 2015

Improving India-US Relations Unnerves Beijing

Chinese state media both denigrated President Obama’s historic trip to New Delhi this week and excoriated American policy in what appears to be a concerted effort to undermine US-Indian ties.

On Monday, an American leader attended Republic Day celebrations in the Indian capital for the first time ever, and Obama became the first US president to visit India twice while in office.

Beijing was obviously concerned, putting forward two broad themes across its media platforms. First, Xinhua News Agency, in a commentary titled “US, India Unlikely on Same Page,”referred to “the superficial rapprochement” of the two democracies, telling readers the visit “is more symbolic than pragmatic, given the long-standing division between the two giants.” Issues, such as climate, agriculture, and nuclear energy,divided the US and India, the commentary, which ran on Sunday, said.

“Three days are surely not enough for Obama and Modi to become true friends,” the commentary correctly remarked. “After all,” Xinhua stated, “only one year ago, US diplomats were expelled from New Delhi amid widespread public outrage over the treatment of an Indian diplomat in New York and Narendra Modi, [now] India’s prime minister and then chief minister of Gujarat, was still banned from entering the United States.”

Given Xinhua’s take, Beijing had no need to worry about the summit, yet worry it did. In its second theme, Chinese media pointed out that America was disrupting the peace in Asia. “The US wants to use India to contain China,” China National Radio stated, also on Sunday.

Then on Monday, Global Times ran a piece titled “India, China Mustn’t Fall into Trap of Rivalry Set By the West.”The “craftily set” trap, the Communist Party’s nationalist newspaper said, was the West “egging India on to be fully prepared for ‘threats’” posed by Beijing. “A zero-sum game is not what China and India are asking for, but under Western influence, India is sliding into it.”

It’s hard to understand what Beijing thinks it can achieve with “commentary” like this. Indeed, Chinese leaders appear to be oblivious to the consequences of their own actions. Beijing’s policy has taken on an increasingly hard edge in recent years, and this has been pushing China’s neighbors away. Indian leaders are not moving closer to Washington because Obama has devised a nasty ambush for them; they are embracing America because, for instance, Chinese soldiers are constantly advancing into Indian-controlled territory along their disputed boundaries.

Beijing policymakers have suffered setbacks elsewhere as well. In Sri Lanka, Beijing’s man, President Mahinda Rajapaksa, lost snap elections this month. In late November, the China-friendly Kuomintang in Taiwan suffered its worst defeat in more than six decades in the so-called “nine-in-one” local polls. The residents of Hong Kong, once proud to be “Chinese,” are challenging China’s rule, occupying streets and plazas late last year. North Korea, China’s only formal military ally, has even branded Beijing an “enemy.” Burmese generals, once China’s most reliable friends, are now turning toward America and the West. Vietnam, where anti-China sentiment is on the rise, these days welcomes vessels from the Seventh Fleet.

And now India has a prime minister determined to defend his country’s borders, even if that means inviting the leader of an old adversary to his capital as guest of honor on his nation’s special day. What Beijing should take away from Obama’s symbolism-rich trip this week is not how far apart the US and India now are but how much they have come together since Modi became leader in May. As Xinhua notes, it was not long ago the prime minister was not even allowed into the United States. In September, he was the honored guest at the White House.

Someone in Beijing should get the message.

OG Image: Asia PacificNorth AmericaSouth AsiaIndiaUSChinaBarack ObamaIndia-US Relations

Asia PacificNorth AmericaSouth AsiaIndiaUSChinaBarack ObamaIndia-US Relations

January 22, 2015

Shifting Relations in North Asia

Discussions this week in Singapore between North Korean officials, led by chief nuclear negotiator Ri Yong Ho, and former special envoy Stephen Bosworth and other American figures ended in calls for the resumption of formal nuclear talks, which have been on hold since 2008. The two-day “Track Two” consultations did not result in any breakthroughs, but the lack of progress in the informal consultations comes amid a flurry of unusual diplomatic activity involving the peninsula.

There was hope in recent days that the Track Two participants might come up with a new blueprint to restart the six-party talks to “denuclearize” North Korea. Instead, Ri used the occasion to lambast Washington and Seoul for their annual joint military exercises, which he termed the “root cause” of problems on the peninsula.

Ri’s comments were not off-the-cuff. This month Pyongyang had proposed a moratorium of its nuke testing if the US and South Korea would end their large-scale drills. Significantly, Pyongyang did not offer to halt its military exercises, which are far larger than the ones in South Korea. The State Department correctly termed the North’s proposal “an implicit threat.”

While Washington-Pyongyang ties remain in the deep freeze, North Korea, South Korea, China, and Russia are reshaping the peninsula. Relations between Beijing and Pyongyang, for instance, seem to worsen by the month. Now, it appears the two capitals are barely on speaking terms, partly a consequence of the execution of Jang Song Thaek in December 2013. Jang, Kim Jong Un’s uncle by marriage, had been the primary conduit between the North and its primary sponsor China. Significantly, Beijing was not invited to the ceremony last month marking the end of the three-year mourning period for former leader Kim Jong Il.

China, for its part, has reacted to the near breakdown in ties with North Korea by following up on South Korea’s initiatives to strengthen diplomacy. In July, Xi Jinping traveled to Seoul, becoming the first Chinese leader to visit the South before going to Pyongyang. Xi has yet to visit his North Korean counterpart.

As China has cozied up to South Korea, North Korea has stayed one step ahead of Beijing by moving closer to Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Putin extended an invitation to Kim to come to Moscow in May for celebrations to mark the 70th anniversary of the Soviet victory over Germany. It now appears Kim will accept. If he in fact goes, it will be his first trip abroad since taking over in December 2011 on the death of his father, Kim Jong Il.

Kim and Putin have reasons to develop closer ties. The North Korean desperately needs a second sponsor, having relied on just one, China, since the end of the Cold War. He requires, for instance, more aid to continue his ambitious byungjin line—“progress in tandem” policy—of developing the economy and nuclear weapons at the same time.

Putin, for his part, knows he needs more takers for his gas. He has to diversify away from his Western Europe customer base and is looking to South Korean purchasers, who as a practical matter are reachable only through a gas pipeline running through North Korea. Moreover, Putin surely understands he has become too dependent on China and could use leverage over Beijing. A good relationship with North Korea is one of the few things he can hold over Xi’s head.

To cement his growing friendship with Kim, perhaps the most interesting long-term development in North Asia, Putin has signaled increasing support of Pyongyang. In April, Russia wrote off about 90 percent—almost $10 billion—of North Korea’s Soviet-era debt.

And what about Pyongyang-Seoul ties? The two Koreas are talking to each other about talking to each other. Park Geun-hye, South Korea’s president, has been pressing unification of the two Korean states by pursuing her Dresden initiative, which takes its name from her speech in that German city in March, and the North Koreans seem to be responding. Kim Jong Un, in his New Year’s address, even raised the possibility of a summit with Park if the “mood” were right.

Today, there is more uncertainty than there has been for a long time in North Asia. The only thing we can say with assurance is that, when the dust settles, relationships on the peninsula will not resemble those of today.

Should we be optimistic that there is so much going on? History tells us that it’s rarely good news when there’s so much news on the Korean peninsula.

OG Image: Asia PacificEurope and Central Asia

Asia PacificEurope and Central Asia

January 13, 2015

Sri Lankans Boot Pro-China Government

Friday, Sri Lankan voters decisively turned out President Mahinda Rajapaksa, Asia’s longest-server leader. By the end of the day, his former ally and health minister, Maithripala Sirisena, had taken the oath of office. Sirisena, 63, had defected from the government camp only in November, just as the election was called.

The 69-year-old Rajapaksa had called the poll two years before the end of his second term, and it looked like a smart move because, even in the days before the balloting, many expected him to win. He had, after all, ended the civil war by crushing the Tamils and in recent years presided over a period of fast growth.

The problem for Rajapaksa was a general perception that he had sold his country to China. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu of the Colombo-based Center for Policy Alternatives told Bloomberg that the Chinese looked like they were “underpinning misgovernance and corruption in the regime.” China, during Rajapaksa’s term, had become Sri Lanka’s No. 1 investor and lender to the government as well as the country’s second-biggest trading partner.

Beijing had flooded the island with about $4 billion in investments. Most controversial in recent months was the plan of China Communications Construction Company to build, in the commercial capital of Colombo, a $1.5 billion “Port City” on a reclaimed plot the size of Monaco. The venture will be the largest foreign investment in Sri Lanka’s history.

If it’s completed. Chinese leader Xi Jinping cut the ribbon—along with Rajapaksa—when he visited in September, but during the campaign last month Ranil Wickremesinghe, Sirisena’s ally and now prime minister, promised he would stop construction. And Sirisena, warning of re-colonization and slavery, rode to office on the pledge (pdf) to end foreign projects, most of them Chinese.

Beijing seems unconcerned. After the election, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei said China wanted to take its partnership with Sri Lanka “to a new height.” “We hope and believe that the new Sri Lankan government will continue with its support to the friendly cooperation with China and push forward relevant projects,” he said. Wang Dehua of the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies is similarly unperturbed. As he told the New York Times, “Many politicians say one thing before elections and do another thing after they are elected.”

Jonathan Holslag of the Brussels Institute of Contemporary China Studies, who has looked at Beijing’s response to coups in five African states, reports that the Chinese have been able to build relationships with new leaders, even ones who campaigned against China. “They all, in one way or another, turn to China, because it was the only player ready to help them finance infrastructure and public spending,” Holslag told the Times. “I assume that this is going to happen with Sri Lanka.”

The assumption would be sound if the new government had nowhere else to turn. Sirisena, however, has a friend in India, just 40 miles from his capital city. Indeed, Prime Minister Narendra Modi reached out to Sirisena immediately following the election.

And the Indian prime minister has many reasons to diminish China’s influence so near to his country’s shores and trade routes. In September, a Chinese diesel-powered Song-class attack submarine and an accompanying sub tender, the Changxing Dao, docked at the Chinese-funded Colombo International Container Terminal, near Port City, which faces India. The Song’s passage through the Indian Ocean was a first for one of China’s conventionally powered boats, and the stopover was the first foreign port call for a diesel Chinese sub. In October, the tender returned to Colombo with another submarine, which may have been the same Song-class boat or, according to some reports, a nuclear-powered one.

The port visits raised “enormous concerns” in the Indian capital. Sri Lanka permitted the Chinese to dock even after Indian National Security Adviser Ajit Doval issued a warning to Sri Lankan Defense Minister Gotabhaya Rajapaksa, the president’s brother, that New Delhi considered the presence of a Chinese sub unacceptable, a violation of a July 1987 agreement providing that “Trincomalee or any other ports in Sri Lanka will not be made available for military use by any country in a manner prejudicial to India’s interests.”

The last thing New Delhi wants is an ongoing and unfettered presence of Chinese vessels—especially submarines—in the waters off its coast. And one way India can complicate the logistics of the Chinese Navy—and narrow its options—is to use its diplomatic charms to deny port privileges to China’s warships.

Those boats may not be coming back anytime soon. During the campaign, Sirisena pledged “equal relations” with India, China, Pakistan, and Japan. That’s code for “no Port City” and “no more port calls for Chinese submarines.”

OG Image: Asia PacificSouth AsiaSri LankaChina

Asia PacificSouth AsiaSri LankaChina

January 6, 2015

East Asia's Population 'Death Spiral'

In 2014, Japan experienced the lowest birthrate ever, the fourth-straight year of record low births. There were 9,000 fewer Japanese born last year than in 2013, according to Health Ministry statistics.

Japan is shrinking as it sets one unenviable demographic record after another. Last year, the population fell by a biggest-ever 268,000. “2014’s population decrease was a ‘record’ but it’s a record that is going to be broken annually for the foreseeable future,” writes Forbes’s Mark Adomanis. “By this point it’s essentially inevitable: every January for at least the next 20 or 30 years there will be newspaper headlines stating that Japan’s population just suffered a new ‘record’ loss.”

Call it a “death spiral.” By 2050, Japan will be “the oldest society the world has ever known.” If the country’s fertility rate remains unchanged, the population will drop by almost a third by 2060 and two-thirds by 2110. And the last Japanese child will be born in 3011.

As Adomanis notes, “Since 1973, Japan has not had a single year in which its fertility rate was high enough for population stability.”

Japan’s total fertility rate—essentially the number of children born to each woman—is 1.4, well below the 2.1 needed for replacement. Japan’s low rate, however, is not exceptional for its region. China’s TFR, despite state media claims, is probably 1.4 as well. South Korea’s rate is 1.3. Hong Kong’s is at 1.2 but falls to 1.0 or lower if mainland women are excluded. Taiwan’s is 1.1. And what is Macau’s? That’s 0.9.

Yes, Japan is a “nation on suicide watch,” but so is much of the rest of East Asia. Once demographic trends are baked into a society—as they are in Japan and the rest of its neighborhood—governments can do little to change patterns. State incentives usually do no more than accelerate births that would have occurred anyway. As is said with only a tinge of exaggeration, “demography is destiny.”

So what is Japan’s destiny? Many are concerned that a shrinking population will not be able to support the extraordinarily heavy debt load that a succession of Japanese governments have incurred. Analysts will not be surprised when growth, which is already unimpressive, slows further.

More worrisome is China, a poorer society where adverse demographic trends in recent years have been accelerating. The workforce began to shrink in 2012 according to the official National Bureau of Statistics, or in 2010 according to the country’s leading demographers—in both cases well before the 2016 date that had been projected by the central government last decade.

The country as a whole will not peak in 2026, as estimated by the US Census Bureau five years ago, or after 2030, as Beijing’s official statistics indicate. Senior official Liu Mingkang, speaking at the Asia Global Dialogue in May 2012, admitted China’s population would top off in 2020, which means it will, in all probability, begin falling a year or two before then. The Chinese, who take great pride in their country ranking as the world’s most populous, will soon be dropped to second place. India will take the crown in no more than 10 years, probably fewer.

For China’s economy, changing demography will be especially consequential. The country’s three-decade bull run was largely powered by the “demographic dividend,” an extraordinary bulge in the workforce created by Mao Zedong’s policy of fast population growth followed by his successors’ strictly enforced one-child policy. Now that China is hitting demographic inflection points, Beijing’s central economic planners will be facing headwinds. By the end of this decade, the two major economies of East Asia will be struggling to overcome inexorable population decline.

Japan is leading the pack downward, but other countries in its region are not far behind. Together, they are headed to near-simultaneous demographic collapses, events without precedent in history.

OG Image: Asia PacificChinaJapanSouth KoreaTaiwanHong KongDemographyEconomy

Asia PacificChinaJapanSouth KoreaTaiwanHong KongDemographyEconomy

Gordon G. Chang's Blog

- Gordon G. Chang's profile

- 52 followers