Laird Barron's Blog, page 50

September 5, 2013

Black Gate Reviews The Beautiful Thing…

September 4, 2013

The Divinity Student serialized at The Weird Fiction Review

You can catch Ann VanderMeer’s introduction to Michael Cisco’s The Divinity Student here.

Michael Cisco is an amazing talent to rival the likes of Ligotti and Aickman.

September 3, 2013

Bitten by Himself

The six best vampire stories in recent memory:

The Wide Carnivorous Sky John Langan from The Wide Carnivorous Sky & Other Monstrous Geographies

“Sunbleached” Nathan Ballingrud from North American Lake Monsters

“The Man from the Peak” Adam Golaski Worse Than Myself

“All You Can Do Is Breathe” Kaaron Warren from Blood & Other Cravings

Two can be found in the Datlow vampire anthology TEETH:

[image error]

“Sit the Dead” Jeffrey Ford

“Things to Know About Being Dead” Genevieve Valentine

September 2, 2013

Giant Among Us: Lucius Shepard

When speaking of Lucius Shepard, you’re speaking of an author who deserves the attention of a scholar or a critic. Because, when speaking of this author, you’re talking about a man who has produced a body of work since the 1980s that is prodigious in volume. A body of work critically lauded for the intensity of its vision and the complexity of its treatment of cultural values, its commentary on morality and violence. This is a writer who’s stories and novels have earned awards ranging from the Hugo to the World Fantasy and a blizzard of nominations besides. He ranks among the most tireless and consistently excellent authors of the North Amercan canon of science fiction and fantasy. It is a matter of record.

If you examine that record–the awards, the chorus of critics who avow his importance, the volume of his output over three decades–it is plain we’re looking at the CV of a writer who stands shoulder to shoulder with the Wolfes, the Disches, the Tiptrees, and the Bradburys. An inimitable stylist with a reliably searing political point of view, he has gifted us with a dark treasury of literature that has done its part to inform and to interrogate as frequently as it has served to entertain.

I came to Lucius Shepard’s work late, very late. I’d heard of him, of course. During a stretch of the 1980s he was ubiquitous on the science fiction and fantasy charts, routinely appearing in pro magazines and anthologies. Alas, due to extracurricular activities, the late ’80s and early ’90s were a black hole in regard to my contemporary reading list.

I corrected that deficiency in the early Aughts when his career accelerated into resurgence. Many of us who discovered Shepard just after the turn of the new millennium have Ellen Datlow to thank. She helmed the famous online periodical SCI FICTION and is responsible for editing a string of hits that include “Over Yonder, Jailwise, “Senor Volto,” “Emerald Street Expansions,” “A Walk in the Garden” and Ambimagique.

There have been novels–Viator, Softspoken, and A Handbook of American Prayer, to name three; and sixteen collections as of today’s count. Each of them as brilliant, caustic, weird, and weirdly gorgeous as one might expect. He is a writer who moves deftly from jazz-inflected noir to Central American flavored magical realism, to outright fantasy, to balls out horror. He can wax polemical and he can smack you across the face with a terrifying pulp yarn. Shepard has absorbed and repurposed the influences of so many classical artists, from Borges to Delany, that he has accomplished what all geniuses ultimately do, and that is to create his own microgenre.

I’m not the one to do Lucius Shepard justice. There are professional critics who have, and will again, step forward to elucidate precisely how deeply the field has been scored by his words. All I can say is that he means a great deal to me. I admire his accomplishments, I applaud his boldness, I envy his vision, I am inspired by his tenacity and his dogged toil. He is a rarity in this trade, the kind of writer who will in some way, large or small, make you better for having read him.

Lucius Shepard

September 1, 2013

Read this!

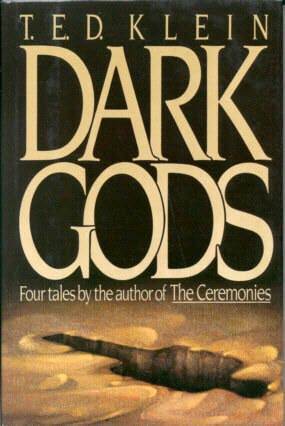

Here’s a link to a recommendation I’ve made time and again. Dark Gods is one of the all time classics of horror and dark fantasy. Get hip to TED Klein if you haven’t already.

The Book I would like to be buried with

August 31, 2013

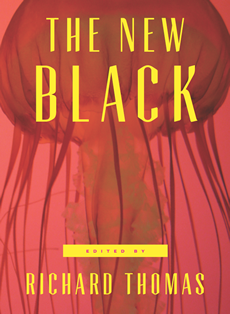

The New Black

I am pleased to reveal I’ve been asked to contribute the foreword to a knockout anthology called The New Black. Contributors include Brian Evenson, Paul Tremblay, and Stephen Graham Jones. Look for it in 2014.

August 30, 2013

It is always the new weird

I don’t recognize the New Weird as a distinct or living movement. I believe in weird fiction, period. Certainly there have been shifts within the culture and these will continue to occur. Lovecraft and Smith deviated from that which Poe and Bierce popularized in their time. Vance, Aickman, Wolfe, and Jackson innovated and redefined when it came their turn. Shea and Wagner took the bit in their teeth, and later Mieville and Harrison. These days, writers such as Jeff Ford, Dan Chaon, Joe Pulver, and Livia Llewellyn are carving their initials in the canon. New Weird is a misnomer, a moving target. For those practicing in this region of the territory, it is always the New Weird.

By now it is no secret that I’m reading for Michael Kelly’s Year’s Best Weird Fiction.

If you have a love of the weird tale, I urge you to contribute to the campaign to fund this inaugural edition. What am I looking for in a year’s best weird story?

I mentioned in a recent interview that any sort of concrete definition of what constitutes a weird tale is fraught with peril. Perilous or not, it’s the task I am charged with in regard to assembling this year’s best volume. To an extent, I am informed by the cynosure of my own taste and experience, my own instinct. However, there is also the tradition and scholarly evaluation of the tradition as a redoubt.

Richard Gavin and John Langan, two of the most erudite speakers and practitioners in the genre, have intimated that the weird is properly a subset of horror, that it is an ingredient, or an element, that may exist to greater or lesser degrees within the framework of a horror narrative. It is an intriguing notion and one that illuminates at least a fragment of the rubric I’ve assigned myself for assessment and selection of weird stories this winter. A weird tale may or may not possess aspects of horror or terror. However, a weird tale, insofar as regards the variety that interests me, is embedded with the fantastic. It produces a sensation of rising unease or incongruity. The laws of physics are mutable, the landscapes alien, explicitly or by implication, and there is no assurance that the path of the protagonist leads anywhere but deeper and deeper into the unknown, and perhaps, the unknowable.

If you would care for a taste of what I consider exemplars of contemporary weird fiction, read Conrad Williams and Brian Evenson; Kaaron Warren and Karen Russell. Read Nathan Ballingrud and Stephen Graham Jones. Aimee Bender, Paul Tremblay, Micahel Cisco, and Steve Duffy. That’s only a taste, but one that comes as close as I can articulate when speaking of what I look for in literature of the strange, the peculiar, the weird.

August 29, 2013

McCarthy

If only Ingmar Bergman were alive to adapt Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. I wish I hadn’t thought of it; now I’ll never know solace.

The Seventh Seal

August 28, 2013

Luke Honey & Miller

I avoid writing story notes, but down the road there’s a project that will require them. So here are a couple of items for those who are interested in arcana.

Luke Honey of “Blackwood’s Baby” is basically my projection of how the Kid from McCarthy’s Blood Meridian might’ve turned out if he’d gone to visit kin in Utah and then hunted big game in Africa instead of going to war in Mexico. It’s not a point for point comparison, the characters aren’t mirrors. Their provenance is merely similar. Nonetheless, Luke Honey’s barely supressed rage, the savagery percolating through his blood, the deep, black hole shot through his soul, is most certainly inspired by what I imagined the Kid as an adult might experience.

“Blackwood’s Baby” and my other hunting story ”The Men from Porlock” were written to mirror one another in the new collection. Miller, the protagonist of the latter tale, has a secret history that isn’t touched therein. We know he was a sniper in WWI, and we know he’s suffering from battle fatigue. But there are other, darker details left unscoped. What I’ll tell you now is a fact alluded to in the text: it was Miller who taught Luke Honey to shoot.

The Beautiful Thing That Awaits Us All

Fight

From a couple of years ago on a blog far, far away:

The Steve McQueen car chase in Bullitt is probably my favorite modern chase. The hand to hand prize is a draw between Bond and the Russian assassin in the train compartment in From Russia with Love; Viggo Mortenson v the heavies in the bathhouse in Eastern Promises; a brutal fight to the death between two characters, don’t remember who or why, in The Deep; and Frank Sinatra v Henry Silva in the Manchurian Candidate.

Pow!

I really enjoyed the techniques Sinatra used as they were a military hybrid of Asian martial arts and western boxing/wrestling–edge of the hand to the back of the neck and sternum, trips, kidney punches, etc.. They appear to have been ripped right out of WWII Combatives devised by W.E. Fairbairn and co., especially the wheeling double chop that misses early on in the conflict. The final bit where Sinatra has Silva down and is wrenching his arm is particularly interesting as that technique doesn’t just cause pain or injury to the shoulder; such quick, brutal jerks send shockwaves up the spine and cause the brain to wobble in its case and was part of a WWII GI knife or bayonet defense–the Germans had a particular bayonet thrust that was their signature close quarters attack and the defense was to sidestep on the weapon side, seize the over-committed arm and yank it hard enough to snap the enemy’s head around, sometimes crippling or killing and certainly disrupting brain to body signals.

In fantasy, its Wesley chasing after Buttercup and the duel with Inigo in The Princess Bride; and Corwin’s hellride and eventual duel with Benedict in The Guns of Avalon. Zelazny sure knew what he was doing.

ETA: my friend Steve Harris pointed out, rightly, that the brawl between Dan and the Captain in Deadwood is among the more visceral things you’re likely to view.