Laird Barron's Blog, page 47

October 4, 2013

Amazon & The Beautiful Thing

Amazon has chosen to make The Beautiful Thing That Awaits Us All a Kindle special for the month of October. 2 bucks is hard to beat. It’s rocketing up the Amazon charts–thank you to everyone who has helped make this book a success.

This collection marks the end of the cosmic horror arc that includes The Imago Sequence and Occultation. Now I’m buttoning up a new book with an Alaska theme–working title of Ardor. There’s a trace of the old lively awfulness in a couple of the pieces, but the majority of the stories veer sharply into psychological horror, crime, and thriller territory. More information to come in a few months.

Meanwhile:

The Beautiful Thing That Awaits Us All

October 3, 2013

Listen to This: Girlfriend Is Better

October 2, 2013

Something Scary: Sauna

In the better late than never category: A friend in the film business made certain I watched Sauna last year–he said, this isn’t like the other stuff, this is special. So, I watched it and have been haunted since. It’s a masterpiece of horror cinema.

An austere, yet gorgeously shot film about the mundane and insidious nature of evil, and possibly the best use of genius loci I’ve ever seen.

October 1, 2013

Read This: Dirda takes on Joshi

Michael Dirda performs a comprehensive review of the eminent S.T. Joshi’s recent treatise on literary horror. This photo is illustrative of the content.

Vincent Price strangling Basil Rathbone in ‘Tales of Terror’ (1962)

everett collection

September 29, 2013

The Tiger Stripe

Here’s a reprint of an essay I did for Centipede Press a couple of years ago. I had it up on the old journal, but that journal is gone, and so too the Centipede link. So here it is again for those who haven’t seen it.

The Tiger Stripe

A while ago, Publishers Weekly solicited an essay about why I write. Lovecraft was the theme. There was more to it, though; more than the word count budget of that article permitted. There always is. And so, here we are.

Sages love this prescription: write what you know. Well, damn, I’ve spent years avoiding what I know, writing around it like a man with a load of stolen hubcaps under his arm trying to sneak past the junkyard dog. I wore down a redwood tree worth of No. 2 pencils as a teen making like Zelazny’s ghostwriter. I tried epic fantasy and Phillip Dick-style science fiction. I plundered Tolkien and Jakes. I was the man on the treadmill on that killer game show in the Bachman Books before I knew who the hell Bachman was. Regardless of what I wrote or how hard I worked, I kept sliding ever closer to my origins in life, the ol’ event horizon that allows nothing to wriggle free.

What I know and how I know are still there, nonetheless; following shadows, provenance that has proved inescapable in the most fundamental sense of the term. I can squirm and struggle, I can flail and fight, but there’s not much chance you’ll get a romance novel out of me in this go around of the big wheel of Karma, and probably not a Pat McManus-style essay, either. Strunk & White and all their prescriptions and all their revised editions can’t change the stars you were born under. Neither good nor bad, this simply and plainly is.

Write what you know, write what you know. Man, that sounds good, sounds pure, it rolls off the tongue, but watch out. Sure, everybody’s got a story. What you know most intimately isn’t the key, however. Poe, for all his travails, demonstrated that. Lovecraft demonstrated that. So did Howard, and so did Wallace Stevens, and Robert service for that matter. No, it’s not the story of ourselves at all. It’s what the story does with you and what you do about it. It’s about other people’s stories, what they do to you, what you do about them. It’s about walking, or crawling as the case may be, through this messy existence with eyes open. It’s about squeezing a fistful of shit and praying for a diamond.

Before my time, my father joined the Marine Corps and ran off to the jungle to fight. He was seventeen. Granddad signed those papers right smartly – he and the boy didn’t get along, not a lick, but then no one got on with Granddad. That southern charm and Bible salesman polish got chipped in a hurry when the heat of his volatile nature overcame him. He’d served as a sailor during the Second Great War, cashiered out right before his ship got sent to the bottom of the Pacific, or so the legend goes. A hard-bitten man, Granddad; not a drinker, but certainly a fellow of towering rages, given to fist and belt when his mood was savage, and it often was. Perhaps he was thus because of all those years dwelling in the cabin he bored and built from a hollow hill in the 1940s, a bear den that became a modern day cave for a contemporary cave family. Alaska is as dark as the pit, but a cave is darker, and darker still is the heart of the man who resides there, like a beast. Maybe he was bitter because of his failed novel manuscripts, or his failed get rich quick schemes, or that he wound up a widower and his children, except a couple of favorites, were scattered on the wind. Perhaps it was a glitch in the genetic matrix. Plain old madness. There’s a streak of that running through both halves and all the branches of my family tree to the core, the heartwood and roots; probably the same as most family trees.

Granddad’s life made an impression on me, and so too his lonely death in the Yukon Territory many years later, but I’ve never written him into a story, never based a character on him. His memory and the consequences of his actions are just a splinter of the fault line running through my mind.

So, he ran my father off, sent him packing overseas to participate in the great Police Action of the 1960s and early ‘70s. Dad survived Vietnam and returned to the States and got married. Funny thing, his replacement stepped on a claymore and got blown in half. Beat Dad out of the country by a week.

I came along and was yet a toddler when the doctors diagnosed me with cancer. There was an operation and I lost an eye and everyone speculated how a baby could get a tumor. Agent Orange, family and friends concluded. Dad had been exposed to many terrible things during his service, industrial grade defoliants among them. He’d acquired a strange rash that bloomed from time to time, igniting near his ankle and spiraling up his body in a morbidly beautiful arabesque that terminated at his neck, just under the hairline. You could plot its trajectory across his flesh. A wildfire, a tiger stripe. A red badge of courage for defense of God and country. Proof enough that something happened to him, that he’d been changed. Proof, confirmed by the melanoma that took a bite of my baby eye that he’d passed along the imprint of metamorphosis like a black gift to his firstborn. Ah, at least cancer is something your parents give you that you can cut out, if need be.

Copyright © ANZAC Day

Dear old Dad knew I was in for hell in public school, what with my weepy composite prosthetic eyeball that always stared straight ahead, dead and icy as that of a stuffed animal, so when I was five he got down on hands and knees and taught me the rudiments of boxing. Nothing complicated, nothing fancy—pivot and drive with the hips straight into the nose or mouth, cross with the right. And repeat until somebody went down. He knew from brawling. There was a scar on his brow awarded in battle during Boot Camp, his nose was crooked from being smashed repeatedly, several of his teeth were sheared close to the gums, consequence of a swipe from a logging boot during a drunken scrum at a party in his youth. Most of the scars were on his knuckles, though. The shallow ones, the ones you could see.

I was a quick study and growing up, I used every dirty trick he ever taught me, from fishhooks to hip throws. Sometimes I won and sometimes I took a beating and I learned to make friends with pain and suffering, because buddy, it was all about pain and suffering no matter what side of the scoreboard I found myself on at the end of the day. A little bit of toughness, a little pride, a little equanimity in the face of fear and loss that served me well whether I was getting my balls kicked up into my lower intestines, or lying at the bottom of a sledbag in a blizzard while my face, hand, and foot froze black, and no sign from the good Lord, just me and the huskies in the howling dark. I’ve Dad to thank for that much.

But I don’t write about him either.

It really wouldn’t make a difference anyway. Hardnosed bastards like Dad were a dime a dozen in rural Alaska, and I bet they still are. When I worked the canneries and construction sites as a lad, everybody – man, woman, child – carried a knife; most kept a gun on hand or near enough. The tenders and the bloody, grimy fishing ports, the quarries and the backwoods shacks, were tenanted by the hardest drinking, crank-snorting, pot-growing automatic rifle toting anti-social scofflaws as any white bread mother in a California suburb could hope to imagine corrupting her college-age daughter when she adventures to the Last Great Frontier for a little summer work experience between chucking her cap and settling in at papa’s law firm. I bunked with plenty of these folks; eight men to an iron room in the belly of ship. The kind of environment where the commissary is always short on razorblades and cough syrup, even when nobody’s got a cough and sure as hell ain’t a one of those hombres wasting time shaving.

Yeah, another thing I’ll have to get around to putting in a story someday. Meanwhile, I keep on chewing what chews on me, and occasionally I spit out the pieces and arrange them like the soggy leaves at the bottom of a cup, and try to divine my fortune. That’s all there is, nothing more.

The truth is, these incidents leave their mark and they become the flaw in the fabric of one’s soul, and whether I deploy them in a fiction or store them in some cabinet in my brain, their essential reality bleeds into everything I attempt, more or less. I don’t often write what I know, but what I know has written the book of me. And daily, I am overwritten. Daily, I am overwritten.

— Laird Barron July 3, 2011 Lincoln, Montana

LD50

Here’s a link to a free story that I had up for a while at my old journal. The journal has departed but the story remains. Check out a day in the life of professional final girl, Jessica Mace.

September 28, 2013

The Black Guide & The Beautiful Playlist

The Black Guide mysteriously–and often with fatal consequences–appears in a few of my stories. Some have compared it to the much more infamous Necronomicon, but that’s not quite right. It’s simply a guidebook, a traveler’s almanac to quaint and curious destinations. I was sitting around drinking with Paul Tremblay and John Langan a few years ago and one of us came up with the idea for the book and how it would be featured by each of us in various stories. So if you keep an eye peeled, you just might find hints of it in work you’d least expect.

Meanwhile, Paul put together a project with students in his high school writing club wherein everybody contributed an entry for The Black Guide. It’s damned cool.

My industrious comrade also sets my new collection to music with The Beautiful Thing That Awaits Us All Playlist. Paul knows his music. And, just like Paul, it’s not safe for work.

September 27, 2013

Watch This: Under the Skin

Under the Skin will be arriving in theaters soon. Based on the novel by Michael Faber, it concerns the sinister machinations of an extraterrestrial visitor as she haunts Scottish highways and byways. The flick looks ultra sexy and ultra creepy.

September 26, 2013

The Arkham Digest

The Arkham Digest is another favorite of mine. Interviews, reviews, and essays–proprietor Justin Steele has the weird genre covered. Go forth and read his latest, an interview with the Thomas brothers.

September 25, 2013

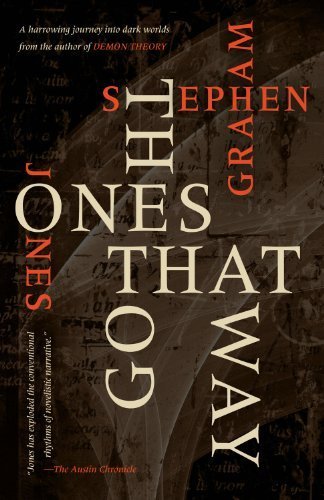

The Ones That Got Away

The Ones That Got Away by Stephen Graham Jones is a tremendous accomplishment. Jones does what he does as well as anyone alive. Here’s my introduction to one of the best horror collections you will ever read.

No Escape

A finger bone vomited into park grass. A snake oil salesman traveling through the land of the dead. A primeval island where the human population of one is about to tick over to zero. A baby monitor that transmits on a damned frequency. Cannibalism. Black magic. Murder. Man’s best friend, until the end. First love. True love. Childhood. Machetes. The Dark.

The Ones That Got Away is a slippery collection; it resists and gnaws at the bonds of genre, yet may be the most pure horror book I’ve come across. The cumulative effect of these stories induces dislocation and dread — the manner of dread that arises from what is known by our soft, weak, civilized selves through rote and sedentary custom and symbolic exchange of cautionary fables, as well as a deeper, abiding fear of the ineffable that’s the province of the primordial swamp of our subconscious. The Ones That Got Away acts as a literary taproot intercepting the delta waves of humanity’s ancestral lizard slumbering in muck. The beast dreaming a future where it has shed scale, fang, and claw, and goes forth on two puny legs, an organism evolved and refined, albeit eternally fettered to its savage provenance via genetic memory and vestigial apparatuses.

Homo sapiens hasn’t come very far, not really. We are quick to anger, quick to draw blood; quick to breed, quicker to flee. From the slopes of our brows to the shelves of our breastbones humans are designed to withstand death from above. While our savage instincts have atrophied, the beast merely sleeps, its lusts and rages merely sublimated, its fears merely quieted. Our collective blissful ignorance of the awesome nature of the universe and our amoebic place therein, as Lovecraft opined, shields us from gibbering madness while leaving intact the basic intellectual curiosity that defines us, elevates us from the beasts. Driven by curiosity and greed, but protected in equal measure by cowardice and short memories, what a contradiction is man.

Stephen Graham Jones is tuned into the phenomena of this duality — the fault line running through rationality, the divide between animal and man, and what we know and the actual truth. With this book he’s acquired a distress signal emanating from the prehistoric brain and committed it to paper, produced an artifact that satisfies the requirements of literature as entertainment while translating on the subliminal register. It is a crystal clear message: all is not well, nothing has ever been, nor will ever be, and that we begin this life covered in blood, screaming. Ultimately, we don’t, can’t, escape the circumstances of our origins.

Childhood lost. Youth corrupted is the touchstone, the recurring theme in The Ones That Got Away. Everything, everything, begins and ends with childhood, for as children Jones’s protagonists dwell closest to the animal state that powers the overmind, are thus privy to, albeit powerless against, the terrible truth, have not developed a thick, insulating shell of incredulity, and are thus scarred, if not damned to be receivers and carriers of horror. Children, with their partially-formed consciousness and absent morality, their natural affinity for the inexplicable, their essential vulnerability, get it, the essence of horror, you see. The wounded ones get it double.

Jones’s adult characters who remain forever those damaged children on the inside, yet devastatingly estranged from any shred of youthful innocence, get it too. These mature protagonists bear the formative wounds and are especially sensitive to the darkness that seeps between cracks, alive as a raw nerve to the intrusion of the supernatural. Cursed with perspective, that bitter fruit of age and wisdom, such men and women cannot help but apprehend the existence of something larger than themselves, its encroachment, how it stains and deforms the fabric of reality, stains and deforms their own flesh and spirit. They are forced to come to grips with the hideous realization that the inequities of childhood, its attendant suffering and imbalances of power, are relative, a socio-economic parallax that persists from birth to death. Good and evil are empty words against the inchoate energies that twist the material world, tears it to ribbons without notice. Like the song says, there ain’t no good guys, there ain’t no bad guys, there’s only you and me. Perhaps the darkest hour anyone will endure is that which succeeds the epiphany that the sublime and monstrous are equally heritable traits. Behind the faces of good and evil, ruination and corruption, lies an insensate vista of blind stars sprinkled across the maw of vast, lightless space.

The pieces herein radiate the dark energy of fairytales. The good kind, the kind with sex and cannibalism, occultism and murder, awe and wonder. Horror. That Jones appropriates this ancient mode, deconstructs and flenses it with his high-pressure stream of consciousness narratives, is grimly appropriate. In his hands, the fairytale isn’t simply a trifle or diversion, nor at heart the sanitized parable so popular in public education, but a fragment of cosmic code, a warning and a promise, the mesmerist’s chime that snaps a mind from one plane to another. Fairytales, the down and dirty ones courtesy Black Forest campfires of ages past, are frightful correspondence with the dark, nightmare communications from the primal wellspring.

Indeed, the power of nightmares defines this collection. Jones’s stories are nightmarish for the clarity of their manifest terrors often hatched from scenarios we’ve envisioned in the wasteland hours between falling into bed and crawling from it. Jones’s stories are also nightmarish for their moral ambiguity and their juxtaposition of the seedy, grimy dirt-in-the mouth taste of reality with that of the supernatural, the diabolical, and the numinous. Yet the experience of them rapidly escalates from reading accounts of discrete nightmares to actually participating in the grotesquerie, becoming entangled, infected, scarred. He’s fractured the big, black picture window that overlooks the benighted regions of the soul. Each story is a fragment of that glass, and some of the imagery is jagged as the hell it evokes.

You can’t go home, can never go back where you started from, is what they say like it’s a tragedy, a curse. There are those who don’t get to leave in the first place. The ones caught in the ankle-hold traps of poverty and abuse, corrupted by the dark days of bad childhoods, the ones who get lost in the haunted forests that surround suburb and city, backwoods shack and brownstone alike. All those kids –now grown into men and women–who dwell on the fringes of the mythical

Great American Dream carry on as shadows of themselves cast down through the long years. Predators and victims by turn. The ones who dream the ancient dream, who can’t quite shake it upon waking and thus remain ensnared, body and soul. The ones who almost got away, but didn’t.

An animal will chew off its own leg to escape the trap, but there’s no escape from a following shadow. There’s your tragedy, there’s your curse. There’s the beating heart of The Ones That Got Away.

–Laird Barron, author of Occultation. April 30, 2010. Olympia, Washington