Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 112

September 1, 2011

The (black and) White River

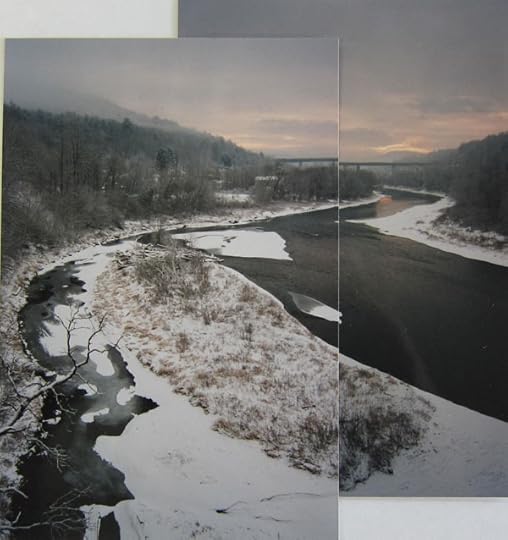

All the recent images and footage of Vermont's rivers made me think a lot about the one I know the best, the White River. Here's a composite photo of the way it looked one winter morning when I was out for my usual walk; this is from the same bridge as in the first video a few days ago, right near our former house. I thought the black and white shapes of ice and water were especially beautiful, and have always been meaning to do an oil painting of this scene, sort of like this one, of an uphill scene a couple of miles away:

Jericho, Vermont, oil, (c) 1985 E. Adams

The trouble is, as beautiful as that river scene is -- the subtlety of the sky and island contrasted with the starkness of ice and dark water -- I'm no longer very interested in doing a realistic treatment of it. After thinking about potential landscapes for another semi-abstract relief print, I got out these photographs and began doing some exploratory drawings a couple of days ago.

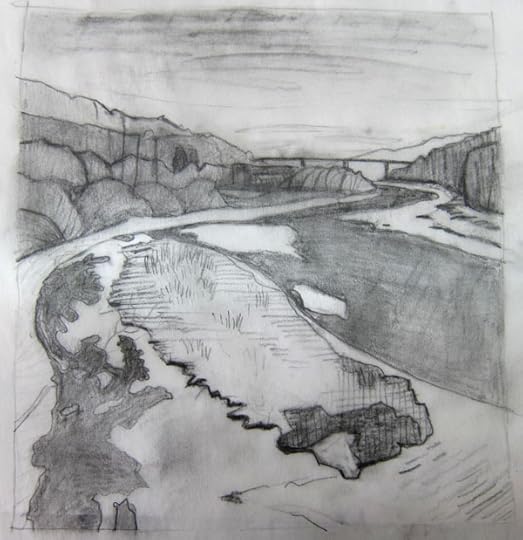

Here's a first sketch, in pencil:

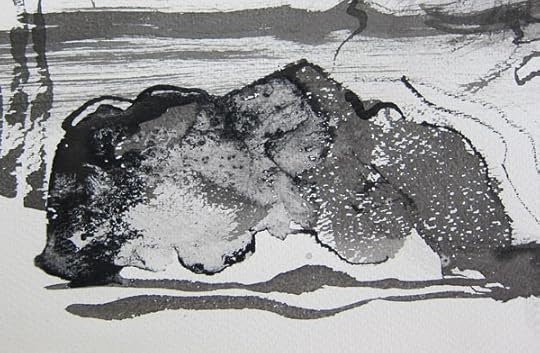

And here's one of several pen-and-ink studies:

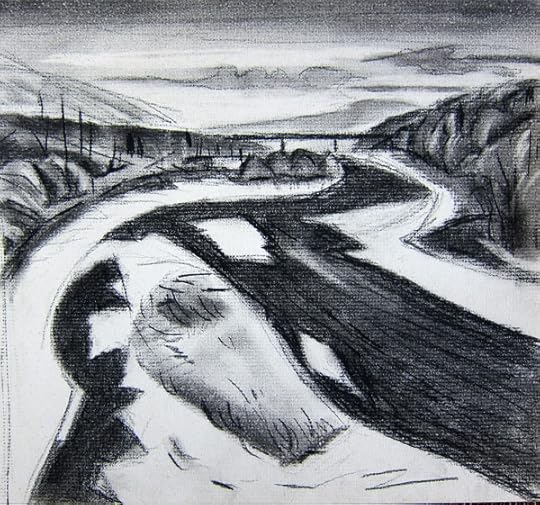

That wasn't making it, but the ink drawings showed me what needed to be simplified and through them I could begin to see how the essential shapes related. I went home and thought about it last night, and today did the charcoal sketch below. I think it's a lot closer to where we're headed, but I don't know yet how I'm going to translate it into a print. I like the drawing though!

What an agonizing process, for an impatient person like me! But I'm starting to settle into it; this seems to be what's required! I appreciated Marly's thoughtful comment about how far certain types of art have moved from this sort of mind--and--handwork process, and how some artists are now moving back. Frankly, I think a lot of serious artists have always done a lot of preliminary work, and returned to certain subjects and motifs again and again.

August 31, 2011

I was just in the mood for a little Pushkin...

August 30, 2011

Irene in Vermont

Here in Montreal, I watched and worried as branches grown to withstand the prevailing northwestern winds of Quebec were lifted backwards, tossed in circles, like helpless arms wrenched by an unseen giant. At 7:22 pm, there was a brown-out. J asked, are we about to become a data point?

But that was nothing. Back in Vermont, there was devastation. The White River, a few hundred yards from our former house, flooded into the basements of buildings, and covered low-lying roads with mud and debris; trees sprouted from the truss-work just below the bridge deck after the waters finally receded. It's very hard for me to believe the river could attain that height; this was the worst flood in Vermont in a hundred years. Here's some video footage from the exact area where I used to live; I crossed the bridge at the beginning of this footage every day.

Many roads and bridges washed out, including some of the historic and picturesque covered bridges that are so iconic of the state. Friends in Strafford and Sharon wrote yesterday to say they not only had lost power, but had no way to get anywhere by car or truck. One of them, fortunately, has a horse. This is footage of the covered bridge in Quechee, Vermont, near the Simon Pearce blown-glass factory and restauraunt that some of you may have visited, also very near our former home:

On the evening before the storm, I was talking to a friend about our love for nature, about how when we're in the country we prefer rustic living because we crave porosity between the indoors and outdoors, and between our own bodies and nature itself: that is the point of being there. And how so many people - both because of nature's violent potential, and because we now live at such remove from it - are afraid of nature, even in its more benign states.

Vermonters are not that way, for the most part, and will get on with it. This is what we all dealt with every spring (footage from the same general area, this is the Ottaquechee River near Woodstock, Vt):

But this flood has been devastating; I hope there will be sufficient assistance of the kind that is really needed. So much of the media coverage about Vermont has been brain-dead; the reporters and do-gooders seem to know absolutely nothing about the place they're standing in. Jim Cantore, of the Weather Channel, was a welcome exception: but he grew up there.

August 26, 2011

Return to Montmorency

Some readers may remember last summer's exploratory series of drawings and paintings of the Montmorency waterfall near Quebec City, where I did this charcoal drawing:

I've had an abstract drawing from that series on my studio wall all year, and this week I went back it as the basis for another relief print. At the top of the post is the block being cut. Here's the back of the print, after a first pass with the round baren, with half the print fully transferred to the rice paper using the back of a wooden spoon.

And here's a finished print from an edition of seven. I like this better than all the paintings I did last year, though I'm still fond of several of the drawings.

When I was younger, I seldom worked this way, delving deep into a subject until it is really internalized. Each piece was kind of a one-off - I'd be inspired by something, do a painting of it, seldom even sketching it first, and that was that. Though working that way can be wonderful, it's an entirely different way of approaching art.

Reading the letters and biographies of artists, as well as studying their work (the recent show of Picasso's guitars at MoMA is a good example) made me want to do more of this "horizontal" exploration, making sketches, playing with different media, trying to see deeply into the essence of a particular subject and my own response to it - what is it that I find compelling? Form? Line? Rhythm? Color? What's my emotional reaction? What can I do with the subject to make it my own? Picasso's inventiveness and refusal to stay in one category or style is an inspiration to me. Gauguin's woodcuts and transfer drawings, which I was looking at this week too, couldn't be more different in mood than Picasso's drawings, prints, and ceramics, but I saw, now, how complementary they are to his paintings; you can see Gauguin working on the subjects, going deeper into their emotional impact and his own psyche. Over in Wales, Clive Hicks-Jenkins returns again and again to his St. Kevin, holding the blackbird's nest, and to the blind saint Hervé, and his wolf, and there's a strong sense that he, too, is looking within.

There's something extremely exciting about moving in this direction, and realizing that a handful of subjects can provide such a rich ground for creative and personal exploration, not just for great artists but for me too, if I have the determination to stay with it over time. "It doesn't really matter what the subject is," a painter and teacher once told me. "You just have to be drunk with it."

August 23, 2011

Process

Spending increasing numbers of hours on the computer, over many years, one can forget (like the proverbial frog in the hotter-and-hotter water) just how far away from home one actually is. For the first thirty years of my life I made things with my hands. For the next thirty, I've made more and more of those things inside this box, including the work of my profession. Graphic design, when I began, was the province of ink and paper, knives and rulers, glue and wax and ruling pens. Even when my own work was done, there would be more ink-on-paper during the printing process: a process that designers needed to understand from start to finish.

We drove past the printing plant of the Montreal Gazette yesterday, with its oversize photographs of newspaper-carrying readers in the windows, and I asked J. how long he thought newspapers would keep on printing paper editions. Not that much longer, he replied, and I agree with him. We haven't gone to an offset printer for a press check in years. Like so many others, we're living and working more and more inside our computers, which have become laptops, and are shrinking further into palm-sized computers masquerading as phones. We walk around the streets holding this customized, self-contained world in our hands, often oblivious to everything else around us - and why not? Everyone and everything we care about, practically, is right there...

But I've noticed, in my recent forays into drawing and printmaking, how much my hands have missed the feel of real materials and the pleasure of movement that turns raw substances into something different: a dress, a knitted hat, a 2-dimensional depiction of reality. I've missed the smell of printing ink, whether relief ink for a linocut or the characteristic smell of a pressroom and newly-printed press sheets in the back of the car. Sometimes, I think, only cooking remains for a lot of people as a way to experience the transformation of ingredients into something we can use in a different way, and enjoy not only for its aesthetic and sensory qualities but for the fact that we can feel, in our hands and bodies, that we made this thing ourselves, by hand.

There's plenty to do in an art studio, even when the muse hasn't come to work yet. Today I opened up (that took some doing) some cans of old relief ink that I thought might be unusable, cut off the thick skin that had formed at the top, and discovered perfectly good ink hiding underneath, away from the air. I cut some new wax paper "skins" to put over the top of the ink, and cleaned up my tools and my hands, covered with smears of oily black and Venetian red. There's something profoundly satisfying for me about even a simple task like that.

Hands are astounding -- have you ever really thought about them? I think we're meant to use them, to experience the most primitive of creative acts, like thrusting them into a vein of clay or mud in the earth and feeling, beneath our fingers, the lump of earth we pull out slowly form into a shape. My mother and I used to dig our own clay from a streambed, and then clear it of pebbles before making it into a figure, or a pot. How many people today have done something like that? This seems, to me, like a much greater change and loss than the printed book or newspaper, and I hardly know where to begin in writing about it, or what it must be doing to our brains and to us as a species. Can we appreciate creation if we don't know what it is to be a creator?

It's not that the computer isn't often a better way - in design, for instance, I'd never argue that digital page payout and typesetting aren't more accurate, easier, faster, leaving more time for creativity and imagination. The results are better, cheaper, more flexible in a lot of ways. I'd go nuts if I had to write this blog post wthout the benefit of a digital text editor! It just strikes me that we aren't using our hands and the brain-hand connection (that seems so intrinsic to the design of the human body) in the same ways anymore, and that this change has taken place, in an evolutionary timescale, overnight.

In the deepest sense, I wouldn't know who I am - I would be an entirely different person - if I had never made things from scratch, using my hands; it is so fundamental to me. I'm not mourning, I'm just rather astonished. And I wonder if the pendulum will swing back again, with young people looking for crafts and artistic pursuits -- as in the revivial of urban knitting -- that show them something different about what it is to be human.

August 19, 2011

"Lao Tzu"

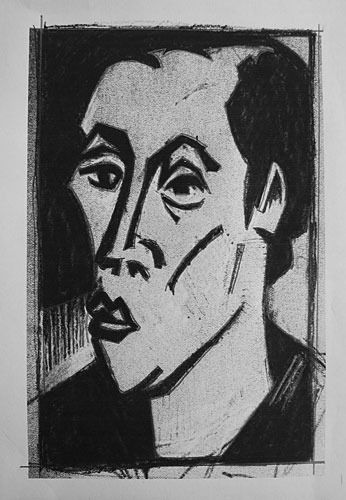

Yesterday I finished cutting the block for this relief print, and printed five copies on two different papers.

This was the inspiration for the print: a very fast sketch of an elderly Chinese gentleman I met on the metro:

Below is the developed drawing from which I did the print. I actually like it better than the print, for its softness, and the lower contrast. Technically the print is better than the last one I did. I'm learning things, and that's good, and was the point of this latest exercise.

A fault of mine: I always tend to hurry, because I never have enough time for all the things I need or want to do. I can often feel this hurriedness in my body, and then I know I need to slow down, relax, take some deep breaths, and do one thing at a time. It's not tension, per se, it's just an inner sense of rushing. In printmaking, rushing can be fatal because one slip can ruin the whole block. You can also cut yourself badly! When pulling the print by hand, you have to prepare the oil-based ink properly, watch what you're doing when you ink the block, and then rub the back of the rice paper deliberately, carefully, and thoroughly to get a good impression, but not so hard as to break the delicate paper fibers. So I enjoyed the process of carving the block and making the prints: slowing down, breathing, cutting with energy but care. I'd like to become good at this, it's a wonderful and satisfying artistic process, right through all the steps, and well-suited to a graphic designer like myself.

As I worked, I thought about the man I'd drawn originally, his quiet calm manner, and the kindliness and wisdom in his old eyes. And he reminded me of Lao Tzu, who then reminded me: "Nature does not hurry, but everything is accomplished."

August 18, 2011

Meanwhile...

...life is so beautiful. After weeks of heat and humidity, we've had a series of the most gorgeous days. The late garden is blooming its heart out, and I've been bringing home tall spears of gladiolus (from the Latin gladius, for sword) in my backpack, which never fails to elicit smiles when I stop my bike at intersections. But it's not just the flowers and the harvest -- displays of corn, melons, berries, peaches, sunflowers, red and yellow peppers, and ripe tomatoes outside the fruiteries -- but a kind of late summer abandon in the way people are dressing, the flowered skirts blowing in the wind, the colorful tops, rakish hats, people streaming into the park with their dinner, their wine bottles, children, balloons. Everyone knows what's coming (the cruel shopkeepers are already putting winter boots and coats in their windows) but it's as if there's a collective, silent pact among Montrealers to wring every last bit of pleasure from the remaining warm, long days.

August 15, 2011

Coping with Societal Change

You know, I wish we could all sit down over tea and talk about the issues raised by the "Feral Capitalism" post and in the comments. I think we'd find that we agreed on many points. Immigration is, to me, an issue separate from the riots, though there are cross-threads. I don't think anyone has suggested that the British rioters were mainly immigrants, but that the lack of jobs is attributable in some measure to the influx of immigrants as well as offshore manusfacturing. And I certainly hope no one is saying that immigrants are, somehow, worse or more neglectful parents. From my own experience in both America and Canada, the opposite might well be true. Immigrants are among the hardest-working people in these societies, whether we are talking about students, fast-food workers, shop-keepers or doctors, precisely because they have come for freedom and opportunity, expect to work hard, and do not have a sense of entitlement.

Among my own close friends, all of whom have tried hard to be good parents, the majority of the children have thrived but there are some who have gotten into genuinely serious trouble, floundered, made a series of very bad decisions, or had difficulty with substance-abuse. Others have suffered from depression and mental illness, seemingly from a variety of causes, one of which is anxiety caused by an inability to cope with the pressures of modern life as adults. Several of these young adults have had problems with managing anger and frustration. "Tough love", counseling, and medication have all helped, but even these have failed at times. Parents who must work outside the home, and are often raising children alone, without the extended families and neighborhoods and churches that used to form the basic structure of social life, cannot possibly counter all the influences to which a child or young adult today is subjected, and cannot protect them from the fears, anxieties, and uncertainties to which we are all subject and from which we all suffer to one degree or another! Violence has come much closer in the West, both in reality and through the media and technology. Parents are primarily responsible for teaching children right and wrong, that is certain, but they themselves have to have a decent childhood where they learned respect and were themselves respected, and to have internalized a personal value system and the skills for passing on. Meanwhile, all around us are examples of people who are seemingly rewarded with wealth and fame for their talent, perhaps, but also for their greed, corruption, and flagrantly consumptive habits; some children are much more susceptible to these pressures than others.

And ever since Watergate, I think we've all grown more aware of the hypocrisy and unfairness that seem part and parcel of politics, government, and institutions. I knew a lapsed Catholic businessman, who used to repeat, "I was taught differently, and try to behave differently, but I've learned that nice guys finish last." In a world where acquisition of money and possessions is a primary goal, who is arguing effecively with that? As religious belief and attendance decline -- as a result, partially, of the hypocrisy of the church, the abuse scandals, and its failure to adapt and speak effectively to modern men and women -- one wonders, actually, why more people don't lie, cheat, and steal. In secular life, one can run up debts and declare bankruptcy with impunity. How many people nowdays believe they'll be accountable in an afterlife, let alone in this one, for breaking the ten commandments, if they even have an idea what they are?

There is a whole constellation of reasons why social values and a sense of participation and fairness have broken down in our societies. My reason for writing the previous post was to try to go deeper than the "bad parenting" answer and ask WHY -- and let's stick to white anglo-saxon culture, since there is no evidence that I've seen to blame these riots on immigrants. In my own WASP family, which has been in the U.S. since the first boats arrived from England, there have been people who've contributed a lot to society and some who have not. Those who have, have fought in the wars and farmed the land and taught in the schools and volunteered in churches and organizations, and raised "decent" children. Yet, like Jean, I feel no sense of entitlement or earned privilege as an American, none whatsoever. I feel incredibly fortunate to have been born free and to have had loving parents who gave me a good education and continued to love and encourage me. I know now that this is far more rare than it should be, but I refuse to judge other people. Instead, I want to try to understand, and to share what I've been given -- especially the love and understanding -- with those who don't have the same.

My husband's family came only one generation ago from the Middle East and Armenia, escaping persecution and seeking education and opportunity. They worked hard, just as my ancestors did when they came here from England. If we had had children they would have been browner than I am, just as the world is gradually growing browner. That's fine with me. I have no attachment to some notion of "American" culture, nor can I even define it: unlike the Tea Partiers, who have a much narrower view, to me American culture is this rich melting pot that results from immigration, mixed cultural contact, and intermarriage. I do not believe in cultural, racial, religious, sexual, ethnic, ancestral or economic superiority; I really do believe all people are created equal and have an absolutely equal right to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Perhaps that's a liberal attitude that's easier to sustain in North America but, after all, it is the founding principle. The difficulty of carrying it out and remembering it ought to be painfully obvious by now, only 235 years into the experiment of American democracy.

The desire for freedom from oppression of all kinds, coupled with the possibility of movement, means that people are going to seek new homes and to mix, and that there will be a subsequent dilution of so-called cultural purity, as well as a loss of ethnic identity in the new homeland. These separate purities, which in their original form gave rise to tribes and nations, have been a source of imperialism, oppression, genocide and war, as well as unique and rich founts of literature, art, cuisine, dress, customs and rituals. No longer separated by geographic boundaries, or even by time and distance, we can neither hide from each other, nor suppress our natural curiosity and hunger for what we see on the other side of the mountain, ocean, desert or river -- or, for that matter, the barbed wire or constructed wall. Human beings will always seek freedom, equality, and a better life for themselves and their children.

Living among the French in Quebec, as part of its English-speaking minority and as one immigrant member of an urban society filled with other immigrants from all over the world, has made me much more conscious of how a small isolated group can feel their unique culture is threatened. (Immigration to Canada is not guaranteed, there is a point system and a long process that must be followed.) But the dark reverse side of cultural preservation is racism. Each society has to decide what matters most, and where their true values ultimately lie: are there ways to offer freedom, openness, asylum, and opportunity and welcome the cultural richness which enhances life, encouraging participation in the society as a whole, while also preserving an existing culture and language? (Shall we ask the indigenous peoples of North America what they think about that?) In Quebec, when some racist (anti-Muslim, most recently) sentiment came to the surface, the whole society engaged in a debate and year-long process with appointed commissioners, because as a nation we wanted to acknowledge the problem of cultural preservation vs. immigration and deal with it openly. I think this will be an ongoing discussion, because it is generally agreed here that racism is unacceptable, immigration is desireable, French culture is valuable, and that we have to find ways of negotiating between the resulting tensions and fears.

Social and economic frustration; changes in values and behavior; loss of the familiar and precious; the breakdown of family and community support and increasing isolation of the individual; the omnipresent influence of technology and media; the diminishing reward of education and hard work; corporate and governmental corruption and greed; violence moving closer to us: these are very difficult issues, and I think we've already recognized here that they are interrelated. I'm glad we can talk about them and try to trust each other.

August 14, 2011

Lots of Happy Mark-Making

In the comments on a recent drawing-related post, my friend Clive Hicks-Jenkins (who is as kind and generous as he is talented) offered some gentle and excellent advice that boiled down to this: "Have more fun! Play!" I needed to be told that, and encouraged. Anyway, Friday afternoon in the studio I got out a watercolor block of good paper; some bottled sumi ink, water, and small pots for mixing washes; a bunch of my old calligraphy tools (I used to be a professional calligrapher, long long ago); a variety of brushes - some standard watercolor brushes, some Chinese; and some stranger objects -- one of my favorite mark-making tools is a stick I whittled to a bit of a point, back in Vermont. And started to play.

The marks began to take on a bit of a landscape-like character, with some of the forms I've internized from drawing the park. And I was having a great time with the Chinese brushes. That was when this "rock" happened. I threw some salt into the wet ink on the left side and loved the result: it's unplanned, and quite free. These are the "accidents" that make art-making fun, and which propel us along. Sometimes there's just one really effective brushstroke or area of vitality in an entire drawing, but if we're paying attention, it can teach us something.

Pointy steel pens tended to catch in the rough watercolor paper, but my stick proved to be a good tool, as did certain brushes and flat-nib pens. A friend brought me the Chinese brushes directly from China, a number of years ago, and I've never really used them. It was exciting to see how different they were from my watercolor brushes, and to discover what sorts of marks I could make with them, held in different ways, and with different consistencies and amounts of ink. The marks below were made with a wide variety of tools.

Yesterday I went back to the studio in the afternoon, thinking I'd start work on a relief print from a very different drawing, a face. But when I looked at the previous day's "sampler" sheet, my fingers started itching and I got out the ink again, wondering if I could make what I had left (below) into a park-influenced painting of sorts.

(click for larger view)

The floating squares were marks made with a special, stiff, square calligraphy tool that I think belonged to my mother - I didn't know what to do with them but I echoed them more faintly to the right, and now think they sort of look like prayer flags. Whatever!

You can click on the final image for a larger view. Thank you, Clive, and thanks to all the readers who've commented on these posts. I had a lot of fun -- and learned a lot in a short time. Full of ideas and enthusiasm right now.

August 13, 2011

Feral Capitalism

OK, a rare rant.

This morning I got a note from a Canadian friend with whom I often discuss politics and religion. He was sending me a link to an article by David Harvey, professor at CUNY, about the British riots, where he picked up on the Daily Mail's phrase "nihilistic and feral teenagers" and wrote about the larger phenomenon he calls "feral capitalism." This was my reply to my friend:

I was appalled by (Archbishop of Canterbury) Rowan Williams' remarks to the House of Lords, and even more surprised that The Guardian, of all places, lauded what he said.

"Feral capitalism" is a perfect phrase for what we're seeing. We are so free to talk about "bad parenting" and "criminality" while our governments bomb innocents, rob billions of dollars from the economies to pay for their wars, send all the available manufacturing jobs offshore, and allow millionaires and giant corporations to evade taxes while cutting social services -- and then are astonished when people who have nothing take the things they want, the same things that are touted daily in mass advertising and the media and give prestige in a society that cares mainly about consumption and wealth. What, exactly, are criminality and morality, I'd like to ask? Shall we go back to the Book of Kings and see what's written there? Perhaps Williams ought to read the prophets as well as the Gospels in addition to Dostoyevsky and Marx!

Then too, we seem astounded to discover large segments of the population who are basically nihilistic. We already know that 50% or more of the people don't vote. They already don't feel they are part of this "society" we're defending; they were dropped from it long ago, especially in class societies like England. In the U.S., which I don't often defend, at least poor kids have a chance of moving up; fewer doors are barred, and rising from poverty through education and hard work is a narrative built into American culture -- look at Bill Clinton -- such people are not successfully discriminated against by people with titles or inherited wealth. I can't help but feel that a backdrop of royal wedding excess, Olympic fever, as well as the constant barrage of media messages have contributed. Michael Adams' charts of trends in North American social values, in his books like "Fire and Ice" show this very clearly and disturbingly.

David Harvey writes:

Thatcherism unchained the feral instincts of capitalism (the "animal spirits" of the entreprenuer they coyly named it) and nothing has transpired to curb them since. Slash and burn is now openly the motto of the ruling classes pretty much everywhere.

This is the new normal in which we live. This is what the next grand commission of enquiry should address. Everyone, not just the rioters, should be held to account. Feral capitalism should be put on trial for crimes against humanity as well as for crimes against nature.

Sadly, this is what these mindless rioters cannot see or demand. Everything conspires to prevent us from seeing and demanding it also. This is why political power so hastily dons the robes of superior morality and unctuous reason so that no one might see it as so nakedly corrupt and stupidly irrational.

But he does go on to point out places where instances that give hope for change. In my lifetime, the "Powers and Principalities," to use Walter Wink's phrase, have only become more powerful, into which the institutional Church is inextricably entwined, so it is hard to imagine the process reversing. I too am appalled by mindless rioting and looting, especially by children, but I am not surprised, not at all.

I was not poor myself, but grew up among the rural poor, and have lived most of my life in mixed neighborhoods where I've interacted daily with disenfranchised people. People whose lives include education, love, opportunity, mentors, expectations, and hope cannot apply their standards to those who have none of those things.

A very small example: I've always grown flowers, both in front of my house and in the backyard. Every year, I'd lose some of the front flowers to poor local children wo lived in Section 8 housing down the street. Once when I saw two girls heading down the street with the hands full of bright tulips, I followed and caught up with them. They stopped, chagrined, and I asked them why they had taken the flowers. "Because we wanted them," one said, with perfect honesty. "Because they're so pretty," said the other, "and we don't have anything like that at home." I told them they could always have some flowers to pick, if they'd ring the doorbell first and ask rather than just taking them. They said fine, and did that.

I don't tell that story to excuse the behavior of the rioters and looters, simply to say that the inequalities have grown far too great, and that "because I wanted them" is a very basic rationale for the non-thinking, impulsive behavior we've just witnessed. Bad parenting or failed education are, of course, huge factors, but in my opinion they're not the end reason but further symptoms of a much deeper underlying problem. These phenomena don't arise out of a vacuum, but against a cultural background of savage, rampant capitalism where great crimes by the powerful -- from the highest institutions to the richest individuals, often in collusion with one another -- are not only unpunished, but rewarded.