Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 108

December 9, 2011

Lichens, Moss, Lava

I know I've been a bit scarce around here, and the reason is that I've been busy for the past couple of months on a new body of work (both writing and art) about place and identity, inspired in part by Iceland. Where that project will end up is not clear, but I'm steadily working on it and will, from time to time, share some bits here. Meanwhile, regular blogging will continue!

Here is the latest piece. I'm putting it aside for now but plan to make some changes on the right-hand central side. These charcoal drawings are fairly large, about 30" x 22", and they look quite different in person; reducing them changes the feeling and impact a lot -- the actual drawing is approximately lifesize. Originally I thought I'd be doing drawings as preparations for prints, but I like these on their own, too, and the process of working on them, in silence and solitude, gives rise to thoughts and insights that I don't think would happen without going through the practice of drawing.

Lichens, Moss, Lava. Charcoal on acrylic-prepared paper. 30 x 22". 12/08/2011. Click for larger view

If you'd like to see a slideshow of the drawing as it progressed, here's a link on Flickr.

And here's something I wrote, during the drawing process:

-----

I've been working on a new charcoal drawing. Lichens, moss, lava. And a succulent plant something like sedum, with stiff pod-like leaves tightly clustered around flexible stalks. The drawing is large, like the first one, but this time I'm working on a painted ground of loosely applied, thin acrylic, toned with Hooker's green, Naples yellow, and a bit of quinachridone red to a slightly greenish cream.

It's the same problem I've returned to again and again in art: the representation of multiple, complex botanical forms. Here they are scrambling over yet another complicated shape — the deeply pitted lava. The advantage of working in black and white is that the forms take precedence, which is what I want. The disadvantage is the sheer complexity of the scene, but without the differentiation nature gives through color. In real life, the sedum is a brilliant viridian against the steely grey rocks, while the late-season moss encompasses every shade from olive-green to white. Color aids our eyes and brain: this is plant, this is rock, this is lichen – the latter of which appears, not entirely inaccurately, to be a life-form somewhat in-between the two.

Since my childhood I've been fascinated by the beauty of small, intricate groups of cohabiting plants one sometimes comes upon in the wild, created around a tree trunk, a fallen log, or an outcrop of rock not by any hand but nature's. I tried, back then, to make my own, bringing child-size mosses, lichens, small wildflowers and seedling evergreens to the deep hollows formed between the roots of the beech trees on the side of our yard. I tended these miniature secret gardens year after year, populating them at times with a small doll or two and enjoying the unplanned visits by beetles and other insects, but never quite believing in elves or fairies. When, long afterward, as an adult wandering in the woods, I would come upon a verdant growth of moss covering a rounded tree stump like a velvet bustier, delicately adorned by clusters of tiny spores waving on thin stalks, the darker leaves of wintergreen, and, perhaps, the tiny crimson hats of British-soldier lichen, I would be suddenly reminded of those childhood gardens and at the same time inspired by a silent, awestruck wonder at such perfection, wrought so effortlessly by nature and imitated with such painstaking care not only by imaginative children but by master gardeners. For it's not only the grand scenes — the fiord and river, the mountain peaks, the endless waves approaching from a distant horizon — that bring me to that sense of wonder and stillness, but also the microcosm, the world at our feet.

I thought of that while drawing today, this sense of zooming out and zooming in. The lichens lay pure and white against the rocks, the largest barely bigger than two hands, a blankness in the center of much greater visual complexity. But such is a glacier, too: a strange expanse of whiteness that seems, in its very silence, to call out to the stillness within us and find an echo.

December 6, 2011

Our Free Press

David Attenborough's most recent BBC documentary series, The Frozen Planet, is being aired in Britain and around the world, but American viewers won't be able to see the seventh and final episode, "On Thin Ice." Why? Because it shows and discusses the dramatic climate change that has occurred on both poles since 1980. The BBC, in a cowardly and self-serving move, decided to offer the first six episodes as a package, making the final one optional because some TV channels might find it "too controversial." Well, guess what -- the US is one of those.This quote is from the New Statesman:

Seven episodes of the multi-million-pound nature documentary series will be aired in Britain. However, the series has been sold to 30 world TV networks as a package of only six episodes. These networks then have the option of buying the seventh "companion" episode -- which explores the effect man is having on the natural world -- as well as behind the scenes footage.

The six-episode series has been sold to 30 broadcasters, ten of which have declined to use the climate change episode, "On Thin Ice", including the US.

In America, the series is being aired by the Discovery channel, which insists that the final episode has been dropped because of a "scheduling issue".

Everyone on the planet should see this episode. From what I've learned, it's not even that hard-hitting or political; countries and policies are barely mentioned. But the facts, and the visual evidence, are so dramatic they can't be disputed, and that's what's so threatening. Well -- we can continue to pretend that what we can't see won't hurt us, but nature is going to change that in fairly short order.

--

Meanwhile, that bastion of the so-called "liberal" media -- NPR -- has aired what's practically a commercial for the domestic use of military drones. I live near the US/Canadian border, and fully expect the drones to be overhead, but the aircraft, advertised as "ideal for urban monitoring," are also being purchased by domestic police departments and may be coming soon to a city near you.

One new type of drone already in use by the U.S. military in Afghanistan — the Gorgan Stare, named after the "mythical Greek creature whose unblinking eyes turned to stone those who beheld them" — is "able to scan an area the size of a small town" and "the most sophisticated robotics use artificial intelligence that [can] seek out and record certain kinds of suspicious activity"; boasted one U.S. General: "Gorgon Stare will be looking at a whole city, so there will be no way for the adversary to know what we're looking at, and we can see everything ."

I doubt if terrorist suspects make up even one tenth of one percent, but we now know that the 99% are not only paying the bills, but they're going to be subjected to unprecedented surveillance and invasion of privacy, with no public discussion and no recourse.

December 2, 2011

Wovember

Shovel Down, by Rachel Rawlins

How did it become December before I learned about Wovember? A month-long project looking at all things wooly and woolen -- that is, everything from sheep to newborn babies in handknit hot-pink swaddling cones (you have to see the photo to believe it.)

Thank you to Rachel Rawlins for the link and for allowing me to re-publish this beautiful and unconventional (not surprisingly) wool-themed photograph of hers from the Wovember Gallery, of a tuft of wool caught on lichen-covered rocks. She's a dear friend, fine photographer, and one of my favorite knitters in the whole world...The picture is titled "Shovel Down" and she writes this about it:

"This is a picture of wool caught on one of the stones of a Bronze Age stone row on Shovel Down on Dartmoor. Archaeologists consider the rows to be ancient field divisions. The landscape, 4,000 years ago, had already been shaped by the cultivation of sheep, the use to which it is still put. Scanty pockets of trees in open pasture. At about this time there is evidence that the people of northern Europe had begun spinning wool and weaving textiles. I love the way this relationship – animal-human-landscape-textile – is so deeply, well, woven. (Also the wool and the lichen. But that's another story.)"

Other favorites: a photograph of the annual Icelandic sheep round-up, and another showing just a few sheep on a road in some astounding mountains in Norway.

Every single photograph in the Wovember Gallery made me happy -- partly because I come from sheep country (Vermont); partly because I've just been in another sheep country (Iceland); partly because I too love to knit and to see what others make out of this best-of-all-fibers, a gift from the animal kingdom to us. Take a few minutes and browse through; you won't be sorry.

November 30, 2011

"Rain, Darkness, Wind, Difficult food" -- Eating in Iceland

This is my contribution to the "Food" edition of the Language/Place Blog Carnival.

We already had an idea, before going to Iceland this fall, that the cuisine might present some challenges. "Rain, darkness, more or less constant wind, difficult food": that's how our friend had described his homeland. We knew, from living next door to these Icelandic neighbors for six years, that the staples of their diet were fish and potatoes, with chocolate and other sweets close behind, and vegetables and fruits bringing up the rear.

Shallow soil, sheep, and sulphurous hot springs behind the hill.

As we became closer, they introduced us to some of their traditional foods, such as "hung lamb:" aged lamb that had been free-ranging on Icelandic mountainsides, and then herded in the fall round-up. Once roasted, it was a dark color, and very delicious, but gamier than the spring lamb we were used to. (The traditional Christmas dish is wild ptarmigan, which we still haven't tasted, but by all accounts it's also delicious.) Icelanders eat all parts of the sheep, including two delicacies we've so far been spared: sheep's face, and pickled sheep testicles.

The Icelandic rite of culinary passage is, of course, Hákarl or fermented shark. It's made from Greenland or Basking shark, which are poisonous when eaten fresh because they contain a great deal of urea and trimethlylamine oxide. In order to render the meat edible, the Icelanders behead and gut the shark, and then bury it in a shallow grave in sand and gravel; stones are placed on top to weight the carcass and gradually remove its water content. In some cases, men urinate on the carcass before burying it. Then it's left to ferment for 6-12 weeks, after which it is dug up, the brown skin removed, and the whitish flesh cut into small cubes.

The Icelandic rite of culinary passage is, of course, Hákarl or fermented shark. It's made from Greenland or Basking shark, which are poisonous when eaten fresh because they contain a great deal of urea and trimethlylamine oxide. In order to render the meat edible, the Icelanders behead and gut the shark, and then bury it in a shallow grave in sand and gravel; stones are placed on top to weight the carcass and gradually remove its water content. In some cases, men urinate on the carcass before burying it. Then it's left to ferment for 6-12 weeks, after which it is dug up, the brown skin removed, and the whitish flesh cut into small cubes.

Our friends served us Hákarl one evening in Vermont, a number of years ago. Elsa was pregnant; she had just been back home to visit her mother and had brought back several jars of the delicacy. We ate it the traditional way: in small cubes on toothpicks, washed down with generous shots of Icelandic aquavit. Someone has decribed the taste as "a strong chewy cheese smothered in ammonia." Most people gag on their first taste; we managed two pieces each, and were immensely grateful for the gulps of liquor; our friends polished off at least half of the jar and I've always wondered if this ritual was part of making their unborn daughter a true Icelander! As for us, we woke in the middle of that night, and were horrified to smell the same strong ammonia on each other's breath, and even coming from our pores. Even now I can't look at the picture of bagged Hákarl without a shudder.

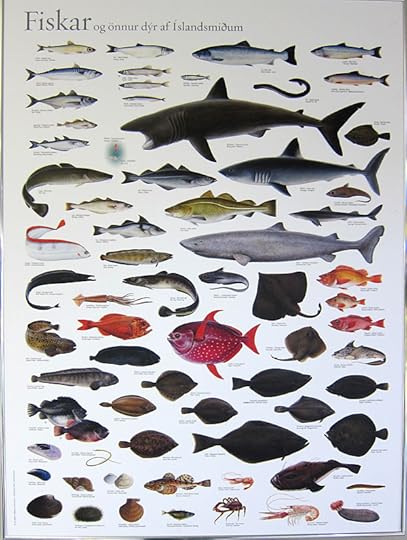

During this trip, we saw Hákarl in the stores, but didn't consume any. Instead we were treated to more kinds of fish than we knew existed, all excellent and fresh from the cold sea.

A surprise, and new favorite, was salt cod mashed with boiled potatoes, the traditional Monday night dinner for many Icelandic children. At one of Reykjavik's finest fish restaurants, this beloved dish was presented in a fancier preparation. That evening we also ate grilled seabird (guillemot - a type of auk):

cod cheeks:

smoked herring with lemon and a wasabi sauce:

and smoked puffin:

Half of the world's puffins gather and breed in Iceland - a total of 8-10 million birds. I learned later that the Icelandic children on the volcanic island of Heimay have a tradition of saving the baby puffins which are born on the steep cliffs and then leave their burrows at night, to navigate by the moon - but are sometimes confused by the town's streetlights. Wayward young puffins are taken home and then released. The same area, however, also has a tradition of harvesting adult puffins; the flesh is usually smoked before they're consumed. It's a bizarre circle, since adorable plush puffin dolls are a kind of Icelandic mascot, available in all the tourist and airport shops.

Except for potatoes, which are available in many colors and varieties, vegetables are few and far between. Very little can be cultivated on the island, with its extremely short growing season and shallow soils -- in the few places where there is arable soil, rather than just lava. There are geothermally-heated greenhouses which supply tomatoes and strawberries, and one that even produces bananas, but most of the fruits and vegetables are flown in at high cost. While there we ate carrots, peas, apples, local wild berries (which were wonderful), local strawberries and tomatoes; mangoes, and orange juice; salad greens are hard to come by except at the height of summer.

Icelanders consume huge quantities of sugar and coffee. Dessert at the fancy restaurant was an Icelandic twist on creme brulee: this is skyr brulee, made from a type of yogurt cheese called skyr, similar to middle eastern Labneh or Greek yogurt, and often served with fresh arctic berries. It was fabulous.

There is excellent traditional dark flat bread, served for breakfast with skyr or slathered with thick fresh butter, and some bakeries still make a leavened dark bread that was one of my favorite foods while on the island. There are delicious tall muffins, baked in paper, filled with berries or apples, and innumerable cookies and cakes, but perhaps the best treats are extremely thin Scandinavian pancakes cooked in butter, served rolled either with a filling of granulated sugar, or of whipped cream and berries. When we lived next door, and he knew we were working very hard, our neighbor would sometimes arrive unannounced in the middle of the morning and silently, smilingly, hand us a plate piled with these wonderful pancakes, still warm from the pan, and just as quickly depart.

I'm currently reading a book called "Fight the Wild Island" by Ted Edwards, an account of a solo journey on foot across the interior -- glaciers, lava fields, and black sand deserts -- in 1984, the first such recorded journey in modern times. Edwards is extremely deprecating about the Icelandic food and its cost, though he praises the lamb. Haldor Laxness's books about the grim lives of peasants certainly don't encourage a visit for gastronomic reasons, but for fish lovers like me, there is endless variety. When we go back, we'll explore the markets more closely; I'm sure there are frozen vegetables and root crops besides potatoes. Meanwhile, the islanders know the value of cod liver oil, and take it regularly!

November 23, 2011

White

We were awake in the early morning, talking as we lay entwined, our heads on the pillows in the half-light, and then fell back to sleep, waking again at nearly nine. J. got up and drew aside the curtain, and came back to bed with his announcement: It's snowing hard.

How much do we have?

Maybe six inches already.

Really! They said snow flurries.

Well, this is a snowstorm.

We were ready, had been ready. Last week J. had gotten the snow tires put on the car, and the Tempo -- a sturdy winter tent erected over driveways and garage entrances that was a final and ubiquitous harbinger of Montreal winters -- had greeted us one day when we returned home on our bikes. And last night had smelled like snow.

A few days before, a Saturday, I had walked to the studio in the early afternoon. It was the first really cold day, so odd for that late in November; like everyone, I had reveled in the extended autumn, knowing that each day was one more subtracted form the long account of winter. But it had gone on too long and become disturbing; I imagined hungry polar bears further north, waiting vainly for the ice to freeze so they could cross it to hunt, and the slow drip of water from glaciers that should by now be locked solid.

My fingers, inside a well-worn pair of red suede gloves, were chilled after just two blocks. I thrust them into my jacket pockets and kept walking, looking for sun. But there was none on the sidewalks of the long narrow northern blocks, even this close to midday; the sun's angle was so low that the shadows had already climbed halfway up the west-facing buildings.

I passed Le Boucanier, the shop of a man recently moved here from the Gaspesie who made artisan smoked fish; the city had already set up a Christmas tree in a large wooden tub outside his shop and others further down the street, awaiting strings of lights. Through the window I saw a new display of handmade breads, stacked in crossways layers like split, drying wood that showed charred patches from a wood-fired oven, and beyond the bread, the small filets of smoked fish lying in a refrigerated case: white, beige, terracotta, rose.

There was, however, plenty of sunlight on Mont-Royal. At the corner of Papineau music blared from an idling car at the intersection, drowning out the first strains of Christmas music piped onto the street by the merchants' association. The Beach Boys. The light changed and I crossed, the car passing me, its window rolled down in spite of the cold.

I walked quickly, my pace slowing once, in front of the florist's window to look at a calamondin in a lovely yellow-glazed pot, hung with perfect orange ornaments, and then again as I turned north on rue Cabot, wondering if the pretty tabby kitten I'd spotted last week would be in the window of a former shop now converted to an apartment. Probably not, I thought, there's no sun -- but it was there, just the same, and yawned and stretched, looking at me with wide eyes when I touched the glass with a red finger. I didn't mind November, though many people seemed to hate it. I liked its suspended quality, the softness of waiting, the re-acquaintance with the bones of the trees.

I was all the way to Laurier before I realized I had been walking at the same pace as the song, ironic and unnoticed, playing over and over in my head: "Do you love me, do you Surfer Girl? Surfer girl, surfer girl..."

--

This morning, we drove to work in a world that had become white overnight. We were behind a huge truck without snowtires, its wheels sliding from side to side, when I heard the song in my head again. The strange idea of lying nearly naked on a beach in California, something I'd never done in my life. On the sidewalk, a woman pulled a blue plastic sled. The light changed, the truck, trying to move forward, slid. Surfer girl.

We pulled into the parking lot and got out. My feet felt the familiar crunch of snow and at this very first touch and sound I knew its wetness, its heaviness, its consistency. I ran my gloved hand along the side of the next car, gathering snow between my palms and squeezing it into a rough, crumbly ball. Then I took a bite and felt the crystals melt rapidly on my tongue; not water: nothing else tastes like snow.

November 19, 2011

L'histoire du ciel

(Thank you to my friend Martine Page, a woman from Quebec whose definitely left a piece of her heart in San Francisco, for this link. Be sure to view it full screen.)

November 16, 2011

Singing at the Oratoire

On Sunday afternoon, our choir sang here. This is the Oratoire St-Joseph, a huge Roman Catholic shrine and basilica on the side of our local mountain, Mont Royal, overlooking the north-western side of the city.

This was the view in the early afternoon, before our rehearsal began. Starting at the parking lot far below this terrace at the top of the building are sets of steps, which pilgrims climb up on their knees. I walked up, but once inside the building I used the escalator -- the most devout go all the way aux genoux. Below the main sanctuary is another chapel, and a shrine room filled with high banks of flickering votive candles, and the crutches of those who believed themselves to be healed by Brother André, founder of this shrine to St. Joseph. Brother André, credited with two "official" miracles but believed by millions to have healed many more, was made Saint André by the pope last year, and the Oratory -- whose grandeur I doubt that simple man could have ever imagined -- is a site of pilgrimage for people from all over the world and one of the most-visited sites in Montreal.

The occasion was a service celebrating 40 years of dialogue between Roman Catholics and Anglicans, and it was mainly about and for the clergy who have been involved with this mutual listening project over the years. We had been asked by the Bishop of Montreal to represent the Anglicans, and we sang both separately and together with Les Petits Chanteurs, the boys' choir resident at the Oratory.

Along with the clergy, we robed in a huge sacristy to the side of the main altar. This is part of our group, getting ready off in one corner of the room.

There were bishops. Lots of bishops.

I quite like the design of the Oratory; some don't. It's very modern, and feels Germanic, which is perhaps odd for Montreal where most of the Catholic churches are ornate, French, and rather baroque. This building has a number of large expressionist wood carvings, extremely beautiful ironwork (the central grille in the photo below, for instance, and you can see some candle stands at the bottom far left), many glittering mosaics (on either side of the grille) and a gigantic organ.

Here's the boys' choir rehearsing; we were seated beyond them on those semicircular benches, behind the crucifix in front of the grille. That rod and semi-circle at the left are a suspension system holding a number of tiny microphones.

They sang Bruckner's "Locus iste," a great piece; they sang the notes well, but (it seemed to me) without much conviction or feeling. We sang a Magnificat and a big Victorian number for double choir, "Hail Gladdening Light," by Charles Wood. In the Oratory's acoutsic, it was quite thrilling to hear our voices, and their overtones, reverberating for many seconds after we had finished the last chord.

And here's the view when I left after the service, around 6:00 pm. I walked down, and by the time I reached my car my knees were protesting a lot! Down a mountain is always worse, for me, than up -- somehow I don't think Saint Andre will be fixing my old ski injuries anytime soon. But one of the great pleasures of singing in this choir is the occasional chance to perfom in different venues and circumstances; this was fun.

November 14, 2011

Remains of the Day

Actually, this couple, with the double-sided green character, inspires me to suggest a caption contest. Any ideas?

November 9, 2011

World Politics: two good articles

"If wealth was the inevitable result of hard work and enterprise, every woman in Africa would be a millionaire:" In The Guardian, George Monbiot ponders the psychology of why the 1% have been allowed to capture so much of the world's wealth.

Many of those who are rich today got there because they were able to capture certain jobs. This capture owes less to talent and intelligence than to a combination of the ruthless exploitation of others and accidents of birth, as such jobs are taken disproportionately by people born in certain places and into certain classes....

...In a study published by the journal Psychology, Crime and Law, Belinda Board and Katarina Fritzon tested 39 senior managers and chief executives from leading British businesses. They compared the results to the same tests on patients at Broadmoor special hospital, where people who have been convicted of serious crimes are incarcerated. On certain indicators of psychopathy, the bosses's scores either matched or exceeded those of the patients. In fact, on these criteria, they beat even the subset of patients who had been diagnosed with psychopathic personality disorders.

The psychopathic traits on which the bosses scored so highly, Board and Fritzon point out, closely resemble the characteristics that companies look for. Those who have these traits often possess great skill in flattering and manipulating powerful people. Egocentricity, a strong sense of entitlement, a readiness to exploit others and a lack of empathy and conscience are also unlikely to damage their prospects in many corporations.

I think that Monbiot's remarks about class distinctions as a prerequisite for reaching top positions may still be more true in Britain than in the U.S., where ambition and hard work actually can propel a person toward the top of their field. But his article quotes the work of several psychologist-economists and rings true, to me, in defining the traits that are rewarded in business, and mirrored in society's adulation and envy.

Until recently, we were mesmerised by the bosses' self-attribution. Their acolytes, in academia, the media, thinktanks and government, created an extensive infrastructure of junk economics and flattery to justify their seizure of other people's wealth. So immersed in this nonsense did we become that we seldom challenged its veracity.

I'd like to see this taken a step further, with a psychological exploration of why we - society - build up cults of celebrity around those with wealth and power, even when it is clear that we have nothing whatsoever to gain.

-----

And from Toronto's Globe and Mail, a thoughtful lament about why there will be no Israeli-Palestinian Spring.

Nor is the unholy alliance that supports Israel the kind of allies we hoped a just and humane Israel would attract. To be adopted by American Christian evangelicals whose ultimate goal is either the conversion or annihilation of all Jews; by far-right European political parties of Muslim-haters who only yesterday demonized Jews; by American Republicans who want to roll back the modern world; by Conservatives in Canada who flagrantly exploit and exaggerate anti-Semitism for their own political purposes; by bogus friends everywhere who insist that criticism of Israel equals anti-Semitism; by the violence-prone Jewish Defence League in Canada, who befriended the English Defence League, a violently anti-Muslim group embraced by Norwegian mass murderer Anders Breivik; by politicians too craven and opportunistic to stand up for the real well-being of Israel, led by the man who used to be Barack Obama. Can such friends really help assure Israel of a secure future?

November 7, 2011

November Elegy

Early November. We've had a late fall, and the weather remains warm. The trees whose branches touch to form a golden tunnel each year over Ave. de Lorimier have dropped their leaves, but in the interior of Parc Lafontaine the autumn colors are still at their peak. Last Thursday evening I left my house at 5 pm and walked through the park, where the late afternoon light filtered through the yellow and red leaves as if through a silky, patterned umbrella. How can I describe the tenderness of this northern autumn light, as the day gently gives way to evening? Like a melancholy song heard from afar, it is blue, diffuse, and soft, but multiplies the intensity of all colors before gradually dying away.

In Iceland this light began much earlier in the afternoon. One day, when J. and I had taken off on bikes, we noticed the sun beginning to go down around 3 pm, and decided we should start thinking about heading back home. But we had judged the signs wrongly. There, so much closer to the Arctic Circle, sunset takes forever. We rode home, and several hours later, still in daylight, Elsa and Hörður suggested a walk to the top of the hill in back of their house, where we stood together, looking over Reykjavik toward the ocean. Even at seven pm the kind of low, glancing light we recognize here as day's final signal still illuminated our faces, and turned the eroded slopes of Mt. Esja, in the distance, into folds of gold and blue.

Last night it was raining lightly, and the wet pavement reflected the sky and branches in the spaces between its pasted mosaic of leaves. I walked down the park's long formal allée of trees toward the fountain, which was turned off for the winter a week or two ago, and then went left along the path above the first of the park's two serpentine lakes, both drained now to reveal pebbled basins coated with green algae.

Just a few weeks ago, the park would have been full of people, on benches and blankets, catching the last warmth of summer, and the sounds of guitars and African drums would have mingled with children's voices shrieking with pleasure as they threw bread to obligingly-eager flocks of ducks and gulls. Today, the paths were nearly empty, and the birds gone. I passed a handsome man with tousled grey hair and a brown leather jacket, riding home on his bicycle, and, at the northern end of the drained lake, a much younger man walked a small dog clad in a dog-coat so brilliantly yellow it mocked the trees.

I passed in front of the park's new cafe-resto, shut tight, its oversize terracotta planters empty now, and stepped onto the path above the lower lake. Here, at last, were the ducks and gulls, splashing in the remaining pool of shallow water. A larger shape stood poised at the top of this pool, and, squinting now in the low light, I saw that it was a great blue heron, an opportunist no doubt drawn here by easy fishing for trapped minnows, or maybe goldfish. One night, returning home in the opposite direction, I'd seen a school of them in the light cast by a streetlamp, shimmering beneath the dark surface like shreds of copper foil. Now the heron presided over his domain: the lord of the manor calmly watching the squabbling peasants, his slate-blue coat turned up at the collar against a north wind.

At the end of the park, I waited for the stoplight and then crossed, keeping out of the way of the cyclists coming off the bike path on rue Cherrier. A young woman waited there for her bus. Tall and slender, with her black hair piled in an elegant knot atop her head, she wore a long black trenchcoat with a cinched waist, and black high-heeled boots. She held an oversized umbrella, the kind golfers use, with an outer border of black and an inner circle of alternating trapezoids of black, and a brown that matched the color of the face that it framed. Calmly, she waited, every now and then raising a cigarette that trailed across this background of black, like a lecturer's piece of chalk.

I had been on my way to the Sherbrooke metro station to catch a train for a 6 pm choir rehearsal at the cathedral. But, after checking my watch, I walked on, mesmerized by the falling light, all the way to the center of the city.