Steve Volk's Blog, page 28

December 26, 2012

The Baby Files

Clearly, I’ve been away. My dream of forming an Existential Questions bureau is delayed, though not denied. The arrival of my boys, Eli and Jack, swallowed up the last five months. Fraternal twins, born four weeks early, our boys have required feedings every three hours, including over night, all this time.

Clearly, I’ve been away. My dream of forming an Existential Questions bureau is delayed, though not denied. The arrival of my boys, Eli and Jack, swallowed up the last five months. Fraternal twins, born four weeks early, our boys have required feedings every three hours, including over night, all this time.

I’ll be posting here with greater frequency now, however, as we are slowly seeing progress in terms of a coherent sleep schedule.

In terms of Fringe-ology, there is some big news. I’ll be on the Joe Rogan podcast, on January 7. For those who don’t know, Rogan runs one of the Top 10 most listened to podcasts in America, and while he happens to be a comedian he is quickly becoming that and something more. I’m thrilled for the opportunity to meet him, let alone appear on his show. I’ll write more about him and my appearance preceding the show. All of this material will be pure Fringe-ology, including some stuff on Sam Harris and further attempts on my part to contextualize James Randi.

In the meantime, though, this post and the next will concern themselves with a column I started writing since the boys were born. First, here is a near-complete list of those columns, each linked so you can dive into anything that might interest you.

June 25, 2012: Men Get Babylust, Too

July 9, 2012: My Wife, a Rock Star

July 23, 2012: A Man’s Guide to Miscarriage

Aug 6, 2012: Confessions of a First Time Father

Aug. 20, 2012: Having a Baby is Like a Second Honeymoon

Sept 4, 2012: Circumcise Your Baby Boy

Sept 17, 2012: Breastfeeding Sucks

Oct 1, 2012: When It Comes to Breastfeeding, Dads Have No Rights

October 15: Is it Safe to Bring Baby to Bed?

Nov 2: A New Parent Advises You to Shut Up

Nov 26, 2012: Thanksgiving, the Twins, the Story of Our First Road Trip

Dec 10, 2012: Men Can Breastfeed, But $150,000 Won’t Be Enough to Make Me Try

December 23, 2012

Confessions of a First-Time Father

The twins were born, and just a few days later I had 1,000 stories. I could tell you about my wife, who did 12 hours of active labor, without the benefit—or risk of complications—of an anesthetic. As she shouted and ululated, I repeated the phrase she told me beforehand she wanted to hear. “The babies are coming.” But the moments that stay with me are when she could barely go on, her body wracked by contractions, and the doula whispered in her ear—in some small space underneath my wife’s moaning—“You’re a warrior.”

The twins were born, and just a few days later I had 1,000 stories. I could tell you about my wife, who did 12 hours of active labor, without the benefit—or risk of complications—of an anesthetic. As she shouted and ululated, I repeated the phrase she told me beforehand she wanted to hear. “The babies are coming.” But the moments that stay with me are when she could barely go on, her body wracked by contractions, and the doula whispered in her ear—in some small space underneath my wife’s moaning—“You’re a warrior.”

I could tell you about Eli, the boy showman who, weighed in at six pounds, one ounce and emerged face up—the most stunning “Here I am!” entrance I could imagine.

I could go on about how the relationship with my kids started before they were born. On our doula’s advice, I sang to the babies from about 24 weeks of development, in Lisa’s womb: “What a Wonderful World.”

See the rest at the source here:

July 26, 2012

Of Men and Miscarriage

The first miscarriage occurred in December, shortly before my wife’s birthday. The second miscarriage happened in May 2011, at the start of Memorial Day weekend, and lasted a long 72 hours till Monday.

The first miscarriage occurred in December, shortly before my wife’s birthday. The second miscarriage happened in May 2011, at the start of Memorial Day weekend, and lasted a long 72 hours till Monday.

As a culture, we don’t talk much about miscarriages.

There is the sense that because there was never a baby to hold that there is nothing to grieve. So when the second miscarriage happened, and we started dealing with the psychological ramifications of losing two pregnancies, we didn’t have anywhere to go.

Some close friends and family helped afterward, people who suffered their own miscarriages and knew it was difficult. But mostly, we were on our own.

My wife, Lisa, cried a lot.

Me? Normally, I cry all the time. Episodes of Parenthood, the sight of my family enjoying themselves, thinking about my wedding day, I could go on and on about the sentiments that can set me off. I’m not John Boehner. I hold it together in front of company and anticipate that if called upon during a Senate proceeding I will be able to refrain from weeping all over the microphone and the text of my prepared remarks. But in private, when it comes to tears, I am lavish and spend them freely. And yet, in response to miscarriage, I couldn’t muster up a single, salty drop.

See the rest here.

July 16, 2012

Big,Thy Name Is Wife

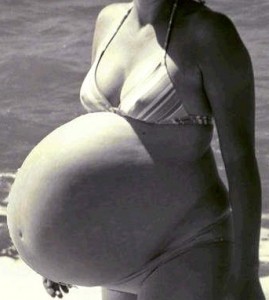

A couple of weeks ago, as Lisa and I wended our way through Whole Foods and Super Fresh, I spent as much time looking at other women as I did at my wife. There was Lisa, 31 weeks pregnant with twins, and I kept looking at every woman we passed. Why?

A couple of weeks ago, as Lisa and I wended our way through Whole Foods and Super Fresh, I spent as much time looking at other women as I did at my wife. There was Lisa, 31 weeks pregnant with twins, and I kept looking at every woman we passed. Why?

Well, please understand: My wife has gained a lot of weight. And if she is the least bit tired, which holds now pretty much all the time, she teeters when she walks. And these other women, on this particular grocery trip, started grinning at her, from 10 or 20 yards away, clearly hoping to catch her eye. But Lisa was so focused on finding frozen fruit bars and ripe bananas she failed to notice them.

A few women simply stepped in front of her and started talking. “Hi!” they said. “You look like you could give birth any time now!”

Lisa seemed content to merely smile in response. But Husband, because I am incapable of containing myself, barked “Twins! Twins!”

Eyes widened. Oohs and aahs sounded. My wife has become a human fireworks show.

Read the rest here:

June 25, 2012

The Daddy Plan

I’ve started a column, over at the Philadelphia Magazine website, on my latest creation.

I’ve started a column, over at the Philadelphia Magazine website, on my latest creation.

*

The plan was to drink a few beers and listen to a couple of friends talk about fatherhood. Both had new babies, around nine months and four months old, respectively, and I hoped the conversation would confirm my own, slowly blooming desire to be a father myself. “So, let’s hear it,” I said, after we sat down and ordered our first round. “Tell me all about the joys of fatherhood.”

One friend, who is dark by nature, averted his eyes and stared at the table. The other snorted derisively. And over the next half hour they talked about the lack of sleep, the constant demands, the strained relationships with their wives, the seemingly never-ending presence of in-laws and the loss of their own sense of place within their home. And then they talked some more about the lack of sleep. And the hours of boredom.

They competed for the bleakest description of fatherhood they could muster.

It’s incredible to me, in evolutionary terms, that our species has survived. Why does anyone ever have children? I mean, I can understand having one out of ignorance. But two?

It’s like a slow death.

It’s like the aftermath of a bomb exploding, where there’s no hope but you’re still alive.

“Wow,” I offered. “I was hoping this conversation would confirm my resolve to have children.”

“Resolve?” the snorter replied. “Let me ask you this: Why would you want to have a baby?”

See the rest here.

May 31, 2012

The Unstoppable Woo of The Fantasist James Randi

For those who need to catch up, I’ve written in the past about the strange case of James Randi, the self-proclaimed truth-teller who spent the last 20-odd years living with a man who stole someone else’s identity.

For those who need to catch up, I’ve written in the past about the strange case of James Randi, the self-proclaimed truth-teller who spent the last 20-odd years living with a man who stole someone else’s identity.

Randi remains a legend in skeptical circles, though the net effect of his high reputation in that crowd is to create an opening for someone like me to point out how little critical thinking skeptics actually engage in when they happen to like the story they’re being spoonfed.

I’m a bit beside myself over this one, though. Because I figured the embarrassment of being caught out with, you know, an identity thief, might cause Randi to back up a step or two from his usual fulminating self-righteousness. Instead, Randi is doubling down on the crazy.

The facts: Randi’s long-term live-in lover, Venezuelan Deyvi Orangel Pena Arteaga, stole the identity of a man named Jose Luis Alvarez in the 80s, in order to stay in the country and travel with James Randi. Working as a performance artist, Pena Arteaga/Alvarez, posed as “Carlos,” a mystic who claimed to be able to channel spirits, at performances staged by Randi himself.

Randi has yet to fully acknowledge whatever role he played in his companion’s con, but the timeline I’ve laid out elsewhere suggests it is very likely he knew about the theft for a long, long time.

Over the years, the real Jose Luis Alvarez, a teacher’s aide in the Bronx, faced IRS investigations because he wasn’t claiming the income actually paid to Randi’s lover. He was himself suspected of identity theft. And when he tried to travel out of the country for his sister’s wedding, he was denied a passport. These sorts of stresses undoubtedly undermine the quality of a man’s life—family weddings don’t occur a second time, and an IRS audit is something I wish upon no man.

At his sentencing hearing, Pena Arteaga apologized for any harm done to the real Alvarez. But not Randi, who was quoted in the newspaper saying: “This was a crime of desperation in which no one was hurt.”

Come again?

I have written before that I think there will be little to no blow-back for Randi over this entire affair. The skeptical community granted him sainthood and stopped looking askance at the depth and consistency of his transgressions a long, long time ago. But his statement in a court of law that no one was hurt is deeply offensive to anyone who has ever been forced to deal with identity theft, in general, and to the real Jose Luis Alvarez, in particular.

I think, however, that Randi has gotten away with so much for so long—again, feel free to look over my past work on the subject here—that he essentially feels he can “create his own reality.” This is the sort of thing skeptics often chortle about—how those silly New Agers read books like The Secret to learn how to think or speak the life they want into being. But essentially, Randi has done exactly that: By speaking of himself in self-righteous tones for decades and proclaiming his own status as a truth teller, he has convinced far too many people that he really is deserving of our admiration, that he really is a truth-teller.

But he’s not.

In fact, my own opinion is that he is a candidate for serious psychological examination. Because this line—”No one was hurt”—reveals the distance between Randi and reality.

After all, in reality, claiming that “no one was hurt” does absolutely nothing to undo the fact: Jose Luis Alvarez was caused a lot of needless stress and anxiety by the illegal actions of Randi’s lover.

But as a magician and a longtime manipulator of the skeptical community and the media, Randi knows perception is really the important thing. So, simply by saying, “No one was hurt,” he will leave a certain number of people, who won’t ever dig into the story, in the dark.

To them, Randi will remain a truth teller and all will be right with the world.

Of course, there is also another, even darker possibility, in which Randi is not simply seeking to cravenly manipulate people with an obvious falsehood. It could be, in fact, that Randi has been weaving this tale for so long now, in which everything he does is right, that he actually believes it.

This would mean Randi hasn’t simply conned the skeptical community and most of the media. He’s even fooled himself.

Some people might see this as an attempt on my part to give the story of James Randi some poignancy.

It’s not.

At this stage, he’s simply a virulent presence.

He is the biggest problem the skeptical community has, and yet they just keep applauding him.

May 27, 2012

Hypnotize Me

Skeptics are still fighting the specter of Franz Anton Mesmer.

I just caught a particularly intriguing article on hypnosis, at Scientific American, covering a study performed by neuroscientists at the Weizmann Institute in Israel. The study seeks to demonstrate just how powerfully hypnotism effects brain activity. And indeed, Scientific American portrays the study as presenting a (further) challenge to anyone who still seeks to deny that hypnotism is, in every meaningful sense, “real.”

This last sentence might strike some as odd. Of course, hypnotism must be real. In fact, even the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has declared hypnotherapy a valid treatment for chronic pain. But Hypnosis, long associated with Franz Anton Mesmer’s debunked claims of “animal magnetism“, remains a controversial topic. And over the years, a steadily growing pile of well-constructed, replicable experiments has done little to quell the skeptics.

There are studies demonstrating hypnosis can be an aid to learning, that it can greatly reduce pain, and that it can dramatically reduce anxiety. PubMed includes more than 12,000 studies on hypnosis now, in various forms, with an impressive array of positive results. But skeptics of hypnotism remain unmoved. In fact, this little treasure can be found at “Skepdic”.

“While it is true that some hypnotherapists can help some people lose weight, quit smoking, or overcome their fear of flying, it is also true that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can do the same without any mumbo-jumbo about trance states or brain waves. There have been many scientific studies on the effectiveness of CBT. For example, one systematic study found that CBT improves weight loss in people who are overweight or obese.”

In all, it is an alarmingly selective and dismissive little tract—dealing with a small number of studies and seeking to explain away any positive results obtained by hypnosis therapy. (At a time like this, I should point out that the “skepdic” moniker actually stands for “Skeptic’s Dictionary.” The unfortunate phonetic pronunciation is, one presumes, an unfortunate coincidence or a kind of sly wink from the skeptical side of the aisle.) And I believe even this new study will fail to convince a skepdic.

I’ll leave you to get the details from Scientific American. But here is an admittedly brief and simplified summary: People who had demonstrated a prior capacity to respond to a post-hypnotic suggestion were shown a movie and told beforehand, under hypnosis, to forget the film until they heard a specific cancellation cue. After hearing the cue, the memories should “come back” to them.

The subjects were then asked about the film while in an fMRI scanner, measuring their brain activity. The results seemed to demonstrate that, due to the hypnosis session, activity in the occipital lobes—responsible for visualizing scenes—was suppressed. The researchers then “canceled” the directive to forget the movie. The details were now accessible to the study subjects, and activity in the occipital lobes correspondingly increased.

This would seem to present a clear physiological effect. Though perhaps a skepdic might argue that the subjects, merely due to the power of suggestion, didn’t really try and recall the details of the movie until they received their audio cue. But my favorite part of the Scientific American article is this:

“Mendelsohn et al.’s study is important because it demonstrates that hypnotic suggestions influence brain activity, not just behavior and experience. Hypnotic effects are real! This fact has been demonstrated clearly in earlier work, for instance, by psychologist David Oakley (University College London) and colleagues, who compared brain activation of genuinely hypnotized people given suggestions for leg paralysis with brain activation of people simply asked to fake hypnosis and paralysis.”

There are a couple of problems here. One, the idea that it takes a brain scan to reveal a subjective experience as “real” is highly suspect. The effects of hypnosis have always been “real,” in the sense that people have responded to hypnosis for pain, anxiety and phobias. The question has been the cause. And the truth is, this latest study will likely do very little to move the needle, culturally speaking.

The Oakley study referenced here was itself published in 2003, nine years ago. (Scroll down to “Differential hemispheric activation for feigned and subjectively ‘real’ paralysis. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 8(4), 295-312″ at this link.) And I am left thinking that the entire “controversy” surrounding hypnosis reflects something my friend Alex Tsakiris, at Skeptiko, often says: “It’s not about the data.”

We’re talking about worldviews here. And to the committed skepdics, hypnotism has been on the outside looking in for so long that, seemingly, no study can convince.

May 24, 2012

The Joplin Butterfly Effect

More than 160 people died as a direct result of the Joplin, Missouri tornado, which occurred a year ago this week and demonstrated the degree to which we remain playthings for nature at its most violent.

More than 160 people died as a direct result of the Joplin, Missouri tornado, which occurred a year ago this week and demonstrated the degree to which we remain playthings for nature at its most violent.

Tornado survivors emerged after heavy winds to find the apocalypse had come to visit. Houses were leveled. Buildings smashed. Cars had been flung like toys to lean against the few trees that had not been splintered, or to lie on top of debris piles.

Thousands were left homeless, and those who lived were plagued by questions: Like how?

As in, how did anyone at all survive such devastation?

It was in the wake of this question that the stories emerged—about The Butterfly People.

The tale took different forms—a mother and her daughter, a grandmother and her granddaughter. But the basic arc is the same: The adult worked hard to keep the child safe, and afterward the child reported that some colorful, winged being—a “butterfly person”—had really done the saving.

This article on the Butterfly People, from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, is in many respects a winning and definitive account—filled with a town’s sense of mourning, and the kindling of hope in a field of despair.

The author, Todd C. Frankel, charts a skeptical path through the tale: Perhaps a single child told a fanciful account, and the story took flight. The details changed as new people heard and reshaped the story in a mystical version of whisper down the lane. Or perhaps someone simply made the whole thing up, and it become a kind of urban legend, growing in the retelling. The people of Joplin, having seen their hometown reduced to sticks, seized on the story for the message it suggested—that they had not been subjected to a tragedy, but a miracle; that they had not seen their town destroyed; but an unlikely number of people saved.

Frankel invests his narrative with reason for doubt.

***

“Shelley Wilson heard the story of the mother and daughter. She works as a high school counselor. After the tornado, she volunteered for a Red Cross disaster mental health team. She drove through neighborhoods distributing supplies, assessing how people were holding up. She doesn’t remember who told her the butterfly people stories. She heard them several times. It was never firsthand — the stories never seemed to come from someone who experienced them.”

***

In a long story, only the following passage seems to allow for the possibility that something unexpected and strange did happen in the midst of the Joplin Tornado.

***

“The stories about butterfly people reached school therapists,” writes Frankel. “Nearly half of all students have had some contact with the Joplin Child Trauma Treatment Center, set up in the city’s schools after the tornado. Dawnielle Robinson, the clinical director, said two therapists heard stories directly from children who said they saw butterfly people.

“Some kiddos said that they had seen some visions of butterflies or butterfly people that helped to calm them or keep them safe,” Robinson said.

Other students reported seeing white lights. The stories came from students with different religious and socioeconomic backgrounds. “It was across the board,” she said.

***

Frankel never references his own experience reporting the story, but I had the sense that he was on a quest to find a primary source—someone who would go on the record and say, “Yes, I saw a light,” or “I saw an angel.” So I called him and asked.

“I very much wanted to find where the story began,” Frankel told me. “It was like a hunt for patient zero.”

He says he pressed the school therapist’s office—hard—but they refused to even approach the family of one of the kid’s for him. “They said they had told me too much already,” he says, “in discussing the content of what some of the kids had said. And they just refused to go any further.”

Frankel says there was also another incident, which occurred while he was reporting, that didn’t make it into the story. A family that he spent a fair amount of time with, the McConnell-Pinjuvs, told him they knew of a little girl who reported seeing The Butterfly People.

“I was thrilled,” he said. “I had done a lot of reporting and I thought, ‘Finally, this is it.’”

The family drove him over to the little girl’s house. But when he got there, the girl’s parents swore she never told any such story.

Frankel says he “doesn’t believe in butterfly people” but he did want to understand the source of the tale. “It seemed like the story did a neat job of explaining something that seemed unexplainable, and maybe that’s why people embraced it.”

According to Frankel, while 160 people died, the number of dead seemed shockingly low given the devastation done to property. “It could easily have been 3,000,” he says.

If he could trace the story to even this one little girl, it would be like touching the beginnings of what the people of Joplin used to begin the effort of rebuilding: Hope.

His disappointment was deep.

“When we got outside,” he says, “the woman who told me about them apologized. She said, ‘I’m so sorry. I don’t know why they did that.’”

Frankel left with his mind on two tracks: One, on how a story can develop a life of its own, can gain power and change shape over time; and two, “I realized how reticent someone might be to say, ‘Hey, I’m the one,’ or in this case, ‘Yes, my daughter had this experience and saw something strange.’”

Like Frankel, I’d love to know the source of the story, and if any primary source—a direct experiencer—exists at all. I doubt I can top Frankel’s boots on the ground effort. But I will make a few calls.

Top 10 Developments in Fringe-ology: 1

Dr. Michael Persinger

COULD THE FIELD OF PSI RESEARCH HAVE FOUND ITS BREAKTHROUGH?

Near as I can figure it, this is the year the debate over whether or not telepathy exists shriveled down to an argument over the statistical analyses common throughout the entire field of psychological research.

As a result, I’d argue the field has reached a kind of crisis point. This development shouldn’t come as a surprise: The period right after I turned in Fringe-ology started with such promise for psi proponents that hardcore skeptics were likely to reach for nuclear options.

Daryl Bem’s paper on retrocausality—can an action taken in the future influence the present?—sparked massive media interest. You can read up on it here. But the upshot is that Bem’s research suggested yes. A storm of coverage ensued, and opponents of all things paranormal leveled a large argument: Not only were Bem’s results flawed, the story went. But, essentially, the entire field of psychology does a poor job of handling statistics, producing false-positive results.

“False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant,” argues that researchers in the field of psychology essentially leave themselves too much wiggle room. For instance, according to the authors, researchers often do not predetermine how much data they will collect before moving on to the analysis phase. Further, they write, “it is common (and accepted practice) for researchers to explore various analytic alternatives, to search for a combination that yields ‘statistical significance’ and to then report only what ‘worked.’”

To be clear, “psi” comes up in this paper just once, and then only in terms of how statistical data are analyzed. There, the authors list a paper critical of Bem’s retrocausality study. I had read this source material, by Wagenmakers, et. al, but only became aware of the “false positive” paper when I saw it referenced in a tweet by the skeptic Richard Wiseman:

“Psychologists,” he writes, “this neatly sums up why some studies appear to support psychic ability.”

He then links to the article.

And there you have it—an entire field of research dismissed in a less than 140 character tweet. Only a hardcore skeptic could make so extraordinary a claim. And given the history of the field, it’s hard not to think that skeptics are guilty—again—of moving the goal posts. As sociologist of science Trevor Pinch told me during my research for Fringe-ology, every time parapsychologists cross some new threshold in terms of the evidence they present, skeptics ask for more.

In other words, for many years skeptics cried that fraud was involved in the production of positive results for psi. Then they cried for stricter protocols to eliminate opportunities for fraud or for subliminal means of influencing the results. With all those calls heeded, positive results have continued to turn up. So the new skeptical battle cry is that psi researchers—and psychologists in general—mishandle their statistics. For a fuller discussion of this trend in the argument, please see my discussion of a paper critical of Bem here. For now, I want to offer up a couple of wishes: First, that the current debate ultimately produces more meaningful and congenial dialogue between skeptics and believers than this field usually enjoys. (As usual, the not so great James Randi is more hindrance than help in this regard.) Second, I want to take a moment to suggest an approach that might, not to put too fine a point on it, change absolutely everything.

*

What I have in mind is a paper from the Journal of NeuroQuantology by Dr. Michael Persinger, who has made headlines many times in the past with his God Helmet.

Persinger is a curiosity to me because his research lands on both sides of the believer-skeptic fence: His God Helmet work leaves little doubt that he is not a believer in God; but his work touting psi or telepathy runs counter to strict atheist-materialist orthodoxy. In other words, where most atheists or materialists seem to hold the position that claims of a God and psi are somehow equal, Persinger is willing to look at these ideas separately. And this paper on Sean Harribance, a psychic he’s studied for many years, advances his argument considerably.

“The Harribance Effect…” includes references to a series of studies Persinger has conducted over the years. He found, for instance, that when Sean Harribance is accessing accurate information the alpha rhythms in his brain increase. Conversely, when the information he is “receiving” proves inaccurate, there is a corresponding decrease in alpha activity. But, as Persinger puts it, those findings are not the wow.

The “wow” is that when Harribance is obtaining information from a human subject whose mind he is supposed to be reading, a correlation occurs between his brain state and theirs’.

“An effect was shown conspicuously in all four separate subjects,” writes Persinger. “As the duration of the proximity increased over the approximately 15 to 30 min period there was increased similarity in the EEG patterns over the temporal lobes of [Harribance] and the subject. The increased similarity was most apparent within the 33 to 35 Hz range. More specifically, there was increased coherence within the 19 Hz to 20 Hz range and the 30 to 40 Hz band for SH’s right temporal lobe and the subject’s left temporal lobe.”

The subjects also reported that Harribance was more accurate when correlations between their brain activity and his was higher. Persinger theorizes, in part, that Harribance might be using his right temporoparietal region to access information from the subject’s left temporal region, an area “associated with the representation and consolidation of experiences that become the individual’s memory.”

*

I won’t argue for or against the validity of Persinger’s study. And I will also acknowledge, for the sake of skeptical readers, that where there is a “wow” there is also a “whoa”—a need to slow down and be sure of our findings. But what I want to stress is that this line of research is worth pursuing.

First of all, if one brain really is sending information to a receiving brain, or one brain really is reading another, we have no idea how such a thing would be possible.

The result is a possible paradigm shift. In the current culture wars, the debate is usually framed as a battle between materialists, who say matter is everything, and those who argue there must be something… more. The battle lines usually shape up, at least in media portrayals, as materialist-atheists to one side and believers to the other.

This puts me in mind of a lecture I saw given by Dr. Charles Tart to fellow parapsychology researchers. Tart argued that materialism is dead, and a chill wind seemed to sweep through the room. Even parapsychology researchers, men and women dedicated to teasing out evidence in favor of telepathy, are largely materialists. So when Tart concluded his talk, silence reigned for several long, awkward seconds before one of his colleagues finally raised his hand and forced a question out of his mouth. “You-, you-, you’re not advocating dualism, are you?” he asked.

The word “dualism” clearly stuck in his questioner’s throat. But Tart smiled genially.

“Maybe,” Tart replied. “I mean, monism and dualism are not our only choices. It could be one-ism, or two-ism or even three-ism. It could even be 2.5-ism.”

In other words, any assault on materialism throws the windows open and what exactly is outside those windows would be an open question. Of course, that’s a big problem, sociologically and psychologically speaking. But is telepathy research really an assault on materialism?

I hasten to point out here that a scientist like Persinger is looking for material explanations for psi. And such possibilities should not be dismissed out of hand. In other words, a materialist universe could be far stranger—and admit far wilder possibilities—than materialists normally admit. Even controversial quantum theories of mind are, at heart, materialist theories, which also—in some hands—allow for the possibility of telepathy and even an afterlife.

But I think we need to set these larger arguments aside, at times. And psi research is one of them. In fact, I think that rather than worrying over the philosophical implications of parapsychology research, psi proponents and opponents and scientists should do something particularly novel here and just, you know, shut up. And do some more science.

Think about it: If other labs could reconstruct Persinger’s study or conduct a similar study that is itself then replicated, subjective statistical arguments about “Bayesian priors” would likely fall by the wayside. Suddenly, we’d have stats and associated physical findings in, theoretically, two test subjects (the “sender” and “receiver,” or “sitter” and “reader”). We’d have multiple lines of evidence that seem to demonstrate some communication directly—there is no other way to say it—from brain to brain.

Of course, one of the things I learned while attending a parapsychology conference in Seattle is that the field of telepathy research is underfunded and understaffed. The barriers to doing this sort of research, then, let alone replicating it in different labs a few times, is extraordinary. But my response to that is so what?

Yes, putting on this kind of dog and pony show will be expensive and labor intensive, requiring expertise and equipment—in the form of perhaps fRMI machines or SPECT-imaging devices—beyond what’s available in the standard parapsychology lab. But after more than a century of pitched debate about the existence of parapsychological phenomena isn’t the prospect of victory worth putting together what might be the most ambitious set of experiments in the field’s history? Isn’t it time, after all this time, to go for a killshot?

I could be wrong. But I bet the prospect of testing so definitive might persuade a lot of potential funders to kick in a few dollars more. And I’d also argue that without so definitive a set of tests we are likely to remain in this position—stuck in a debate without end, mired in a pitched battle with people more worried about their worldviews than the data in their hands.

April 29, 2012

Top 10 Developments In Fringe-ology: 2

The Near Death Experience: Still Undead

While other fields within the paranormal seem to fade in and out of the conversation—look at the dearth of psi-related happenings immediately preceding and directly after Daryl Bem’s precognition study—the Near Death Experience nearly always seems to offer some new development to discuss.

While other fields within the paranormal seem to fade in and out of the conversation—look at the dearth of psi-related happenings immediately preceding and directly after Daryl Bem’s precognition study—the Near Death Experience nearly always seems to offer some new development to discuss.

Working in its favor, the NDE has a fantastic and ever-growing compendium of cases at the website of the Near Death Experience Research Foundation, run by Dr. Jeffrey Long. But in the months since I finished Fringe-ology there has also been no shortage of news.

Illinois woman Julie Papievis had her NDE story optioned into a film this year by the same production team that made the hit movie The Blind Side. The Daily Herald, a suburban Chicago newspaper, reports that at 29 Papievis suffered a horrible traffic accident. Her injuries were so great she had to be resuscitated and fell into a coma. Her brainstem was “all-but severed,” according to the account, yet she retains a distinct memory of being visited by her two deceased grandmothers. They told her to come back and keep living. (This seems like a story worth following up on; perhaps I’ll give her a call and see if she can offer some supporting evidence of her injuries.)

The Colton Burpo story lit up the book charts, chronicling the NDE of a four-year old boy. This story is most noterworthy because NDEs with specific, religious content are a rarity, rendering Burpo’s story a statistical anomaly for hewing so closely to his parents’ beliefs.

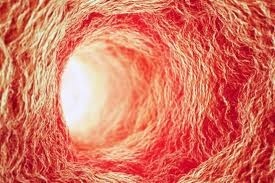

The year 2011 ended with NDEs gone viral—namely, Ben Breedlove’s two YouTube videos, documenting his illness and his Near Death Experiences. I posted Breedlove’s videos earlier here with no analysis. But to give my take, I found the story quite moving. Breedlove unveils a series of flashcards, describing a life he spent living in particularly close proximity to death due to a condition called “hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.” The illness thickens the heart, forcing the organ to work increasingly hard to pump blood. It is difficult to understand the pain this might cause, both physically and psychologically. The disease acts as a boa constrictor, slowly tightening its coils. But Breedlove describes all this, including a vision he had during a close brush with death, with a satisfied, contented and warm expression.

The kicker is that Breedlove died shortly after shooting these videos, on Christmas day. And his peaceful demeanor in these shorts suggests he “fits” the NDE profile: The vast majority of those who experience the NDE are greatly changed, rendered more spiritual by the experience. Yet his story, too, violates one of the chief statistical truisms of the NDE. Rarely do experiencers see a living person. Breedlove, however, saw the very much living rapper Kid Cudi. It’s tempting to dismiss that vision as something other than a Near Death Experience. And of course it’s possible that he hallucinated or grafted the “memory” of Cudi into hi experience later. But there is also the chance that the consciousness we experience after the death of the body—if indeed we experience consciousness at all—allows the new reality we’re in to mix with personal thoughts, a merging of objective and subjective realms.

Whatever the case, Breedlove’s story, as told in two videos, has now tallied more than 10 million views.

To me, however, the biggest development is that the Near Death Experience remains, well, so alive.

The NDE has been remarkably consistent over time. Though there is variability in the experience, historical accounts dating from before the phenomenon got a name in 1975 do seem to describe the same event. So the power of suggestion simply does not work as an explanation. And the pattern of distressing NDEs makes it hard, if not impossible, to argue that wishful thinking is at play. Further, as the years have passed, skeptics have responded with a remarkable variety of arguments, which total up to, by now, more than 20 potential explanations. If the skeptics are to be believed, anoxia, carbon dioxide, ketamine, repressed memories, overactive temporal lobes, seratonin, REM intrusion, cardiac massage, lucid dreaming and more are at work (not all at once, of course) in the NDE.

The deluge of possible causes reminds me of the Onion spoof news article that purported to “solve” the Kennedy assassination: “KENNEDY SLAIN BY CIA, MAFIA, CASTRO, LBJ, TEAMSTERS, FREEMASONS,” reads the priceless headline.

To skeptics, the experience is clearly a brain-based illusion. But I placed this particular item so high on my list because I think it is the one area where skeptics are most clearly suffering a kind of brain-based illusion all their own. To me, it simply follows that neurological explanations require skeptics to find some association between the circumstances of the experience, the content reported, and what we know about brain function. In other words, until skeptics deliver a working model explaining how the different circumstances NDErs find themselves in at the time of their experience produce predictable changes in the content and character of what they report, they have yet to produce any scientific explanation at all.

As an example, people lacking oxygen at the time of their experience should report something different than people who had plenty of oxygen. People under anesthesia should describe something different than people under the influence of no narcotics at all. After all, if I took a shower under some form of anesthetic or with something impeding my ability to breathe, it would be a far different experience than if I took a shower with no such variables in play, right?

Let me be clear: The current lack of such a model for how Near Death Experiences are produced doesn’t mean no such explanation or combination of explanations will emerge. It doesn’t mean the Near Death Experience does or doesn’t represent a glimpse of an afterlife. But what I am arguing is that because skeptics have thus far failed to produce that model the NDE represents a continuing, deepening mystery.

Quite recently, Dr. Mario Beauregard and co-researchers recorded a case involving veridical (verified, accurate) perceptions in a patient undergoing emergency surgery. The patient, a 31 year old they call J.S., was undergoing a procedure called hypothermic cardio-circulatory arrest, very similar to the famous Pam Reynolds “standstill” case. The authors write: “J.S. did not see or talk to the members of the surgical team, and it was not possible for her to see the machines behind the head section of the operating table, as she was wheeled into the operating room. J.S. was given general anesthesia and her eyes were taped shut. J.S. claims to have had an out-of-body experience (OBE). From a vantage point outside her physical body, she apparently ‘saw’ a nurse passing surgical instruments to the cardiothoracic surgeon. She also perceived anesthesia and echography machines located behind her head. We were able to verify that the descriptions she provided of the nurse and the machines were accurate (this was confirmed by the cardiothoracic surgeon who operated upon her). Furthermore, in the OBE state J.S. reported feelings of peace and joy, and seeing a bright light.”

The full write-up, “Conscious mental activity during a deep hypothermic cardiocirculatory arrest?” is available in the January 2012 issue of Resuscitation and can be found here.

Beauregard and his co-researchers admit they cannot be certain the 15-minute subjective experience occurred during the 15-minute cardio-circulatory arrest. But, they write: “Nonetheless, the tantalizing case of J.S. raises a number of perplexing questions. For this reason, we hope that it will stimulate further research with regard to the possibility of conscious mental activity during cardiocirculatory arrest.”

That last line, about “further research,” is the final point I’d like to hit: In the battle over worldviews—do we suffer the same fate as meat? Or do we have a consciousness that continues beyond death?—we often seem unable to admit that we really don’t have an answer yet. In this sense, the NDE represents one of those fields that has essentially been hijacked by philosophical agendas rather than studied in careful, rational and patient terms.

Usually, skeptics hold the line against calls for further research, portraying the paranormal as somehow frivolous. Usually, this part of the argument is contextualized as a plea to see scientific research funding and brainpower applied only to worthy and credible causes. But in the case of the Near Death Experience this argument doesn’t really carry any weight.

Skeptics and believers all agree that death provokes great anxiety, often detracting from the quality of the life we live. Yet the great majority of people who undergo NDEs no longer fear death.

If this “cure” for death anxiety is purely the product of brain function—in a materialist sense, the secretion and absorption of various chemicals—then pinning down the exact mechanism that makes this possible seems the most humane thing we could do for ourselves and each other.

In this sense, the skeptical position of “go on about your business, there’s nothing to see here,” seems not only bankrupt of evidence—but simple decency. And the Near Death Experience, 37 years after Raymond Moody first coined the term, simultaneously sheds light on death and retains its deep sense of mystery.

Steve Volk's Blog

- Steve Volk's profile

- 18 followers