Steve Volk's Blog, page 24

February 11, 2015

Best 2015 Innovations in the Appliance Industry

We all benefit from any type of innovation in the appliance industry, because innovations ease our work considerably.

You should read the following lines to find out what are the best 2015 innovations in the appliance industry, and if you are impressed by them, maybe you’ll even upgrade your old appliances.

[See image gallery at stevevolk.com]

Best dishwasher innovation

Definitely the best 2015 innovation in the dishwasher industry comes from the manufacturer Whirlpool.

Their 6th Sense Live technology makes the dishwasher keep up with the modern internet controlled time that we live in, this technology connecting to the local WiFi network to be able to bring you the benefits of a smart grid system.

The 6th Sense technology dishwashers from Whirlpool have a price that surpasses other comparable models by only $200, and for this reasonable amount of money, you can have a dishwasher that determines for itself when energy consumption will be the least expensive, starting to wash the dishes only in that moment.

You can enjoy this amazing innovation by simply pressing the Smart Grid button that will instruct the appliance to run only when consumption is at its lowest, helping you save a lot of money on the long run. If you want to learn more about this type of dishwasher, you should visit bestdishwasher.reviews. There, you will find comprehensive reviews which will also help you compare these dishwashers with other competitive models.

[See image gallery at stevevolk.com]

Best refrigerator innovation

When it comes to the best innovation in the refrigerator industry, the winner of 2015 is the T9000 model from Samsung which brought us the Triple Cooling System technology.

The Triple Cooling System feature of this amazing 23 cubic feet refrigerator enables individual temperature control for each compartment, and it enables the optimal humidity as well. This is possible due to the fact that it creates three separate air flows in the freezer and in the refrigerator.

This innovative cooling feature enables the refrigerator to feature the Cool Select Plus feature, a feature that basically gives you the option to control the compartment located in the lower right part of the refrigerator by allowing you to convert it from a refrigerator to a freezer and back again. This special compartment has the capacity of 4.43 cubic feet, and it includes 4 customisable temperature settings for you to choose from.

[See image gallery at stevevolk.com]

Best dryer innovation

The best 2015 innovation in the dryer industry comes from the respected manufacturer Whirlpool, that brought us the HybricCare technology.

What this technology basically regenerates energy during the drying cycle by using an ingenuous refrigeration system to dry and recycle the same air, making the models which use this technology be the most energy efficient dryers available.

The HybridCare technology uses its advanced sensors to professionally manage the drying temperature, giving the laundry which you dry with it the best care possible.

Definitely, Whirpool have set an example of themselves in the appliance industry by using this amazing technology, making them the most environmentally friendly appliance manufacturers today.

January 7, 2015

Top 5 of the Moment

5

I Believe You Gotta Serve Somebody

I was catching up on some reading the other day when I ran across a piece by New Yorker writer Sasha Frere-Jones on The Basement Tapes Complete. “In October, 1979, Dylan and his band were playing ‘Gotta Serve Somebody’ on Saturday Night Live,” he writes. “… Dylan sang, or spoke, lyrics about ‘the heavyweight champion of the world,’ someone with ‘women in a cage,’ and ‘the head of some big TV network,’ and about how, at the end of the day, these big cheeses all had to serve somebody. I was twelve, and even then I could tell that he was setting up straw men as some ridiculous proof that religious faith was universally necessary.”

I was catching up on some reading the other day when I ran across a piece by New Yorker writer Sasha Frere-Jones on The Basement Tapes Complete. “In October, 1979, Dylan and his band were playing ‘Gotta Serve Somebody’ on Saturday Night Live,” he writes. “… Dylan sang, or spoke, lyrics about ‘the heavyweight champion of the world,’ someone with ‘women in a cage,’ and ‘the head of some big TV network,’ and about how, at the end of the day, these big cheeses all had to serve somebody. I was twelve, and even then I could tell that he was setting up straw men as some ridiculous proof that religious faith was universally necessary.”

There are a lot of problems with this passage. (The bit about recognizing a straw man argument at 12 was perhaps best left unwritten.) What really caught my attention, however, was how casually he tripped over his biases. Frere-Jones allows (evidently from the age of 12) his own irreligiousness to blind him to any interpretation of “Gotta Serve Somebody” other than the most literal possible. Maybe the fault is my own ecumenical background, where metaphor—even in religion—is acknowledged. But “Serve Somebody” remains one of the rare gems from Dylan’s too-slickly produced Christian period. And Frere-Jones’s rejection of the song itself smacks of superstition.

Writing of God and the Devil in a manner that even permits a literal interpretation isn’t really the same as preaching, and 30-odd years on, Dylan’s old blues tune still smolders with conviction, both religious and secular. I mused on this to a friend who suggested I listen to Dylan’s “I Believe in You,” from Slow Train Coming, another overlooked victory from Dylan’s Christian period. Recalling The Platters’ “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes,” Dylan sings, “They asked me how I feel, and if my love is real.”

He could be singing about a wife, lover or God. I’m not only all right with that, but found myself playing the track on repeat. “I believe in you even though we be apart,” Dylan sings, his voice cracking, and “I Believe In You” emerges as a devotional with universal appeal, a love song it would take a narrow view to interpret any more narrowly than that.

4

The Torture Report

Like many Americans, I was mortified by the details included in the recently published Senate Committee Report on CIA torture. I won’t recap any of the details here, but I found some solace in the mere fact of the report’s existence. America, for all of its flaws (many of which are evidenced in the Report itself), is a country given to self-correction. While it strikes me as deplorable that we took up such a devil’s bargain—endeavoring to stay safe on the high road by getting down in the dirt— putting our own bad behavior up on a billboard and asking for comment suggests there is great hope for us yet.

3

SUE (Or in a Season of Crime)

Original tracks added to greatest hits compilations usually aren’t all that original, ranging from remakes like “Don’t Stand So Close to Me ‘86” from the Police to new songs that trade on past glories, like The Rolling Stones “Doom and Gloom.” Bowie’s “SUE (Or in a Season of Crime)” is something else altogether. At once sinister and grand, the seven-plus minute version of “SUE” is an epic conflagration of tastes not previously married: experimental jazz and American murder balladry, a genre associated with blues and country music. The jungle rhythm that threatens to tear the whole carefully orchestrated production apart from the bottom up acts—intentionally or not—as a rebuke to Bowie’s critics: If Bowie only pursued Jungle music for 1997’s Earthling in a vain effort to sound contemporary—the usual conceit—why is he still mining that field?

Original tracks added to greatest hits compilations usually aren’t all that original, ranging from remakes like “Don’t Stand So Close to Me ‘86” from the Police to new songs that trade on past glories, like The Rolling Stones “Doom and Gloom.” Bowie’s “SUE (Or in a Season of Crime)” is something else altogether. At once sinister and grand, the seven-plus minute version of “SUE” is an epic conflagration of tastes not previously married: experimental jazz and American murder balladry, a genre associated with blues and country music. The jungle rhythm that threatens to tear the whole carefully orchestrated production apart from the bottom up acts—intentionally or not—as a rebuke to Bowie’s critics: If Bowie only pursued Jungle music for 1997’s Earthling in a vain effort to sound contemporary—the usual conceit—why is he still mining that field?

“SUE” works best, however, without further reference to the singer’s own career. Bowie’s decision to cast a murder ballad—“I pushed you down beneath the weeds”—against so sophisticated a backdrop (his backing band here is the Maria Schneider Orchestra) seems anything but accidental. From factory to field, from shotgun shacks to moneyed estates, the impulse to love can turn into the intention to destroy with terrifying speed.

2

My Brakes

Years ago, as a child, my uncle would take me out sometimes when he ran errands around the city. If he felt the car behind him drew too close, he slammed on his breaks. He’d laugh heartily as the other driver fell back. I only realized the danger he was putting us in when I got behind the wheel myself. I recalled this recently because of late I have been driving some country roads, where locals know each curve so well they tend to take even the sharpest of turns at high speed. A few drivers have essentially hitched themselves to my bumper, as if they think I’m going to speed up on unfamiliar roads because their headlights are filling my rearview mirror. In response, I’ve developed what I come to call “The Modified Uncle.” I tap my breaks, like I’m keeping time to a rainfall. No one is ever at risk, but seeing my break lights flash on and off at a steady rhythm has the desired effect, granting fellow motorists a renewed sense of patience and restraint as they fall back a couple of car lengths.

1

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy by Eric Metaxas

I spent the last few weeks, twins permitting, plowing through Bonhoeffer. For those who don’t know, Deitrich Bonhoeffer was a German theologian and pastor who saw through the Nazi party’s thinly veiled attempts to turn the church into a pagan, state-worshipping institution and tried to do something about it—from fighting for the church’s independence and traditional beliefs to plotting to assassinate Hitler. The book is sprawling, comprehensive and meticulously plotted, with enough historical detail to make you feel the weight of each decision Bonhoeffer made on the way to his own personal destruction. The result is a tale of personal triumph—of the deep victory inherent in acting according to your highest principles, whatever the cost.

I spent the last few weeks, twins permitting, plowing through Bonhoeffer. For those who don’t know, Deitrich Bonhoeffer was a German theologian and pastor who saw through the Nazi party’s thinly veiled attempts to turn the church into a pagan, state-worshipping institution and tried to do something about it—from fighting for the church’s independence and traditional beliefs to plotting to assassinate Hitler. The book is sprawling, comprehensive and meticulously plotted, with enough historical detail to make you feel the weight of each decision Bonhoeffer made on the way to his own personal destruction. The result is a tale of personal triumph—of the deep victory inherent in acting according to your highest principles, whatever the cost.

December 31, 2014

The Dad Files: The France Test

As the father of two and a half year old boys, I feel almost constantly pressed for time. I am either taking care of the boys, or trying to pack as much productivity as I can into the moments when I am not taking care of the boys. The best coping mechanism I’ve discovered is something I call “The France Test.”

As the father of two and a half year old boys, I feel almost constantly pressed for time. I am either taking care of the boys, or trying to pack as much productivity as I can into the moments when I am not taking care of the boys. The best coping mechanism I’ve discovered is something I call “The France Test.”

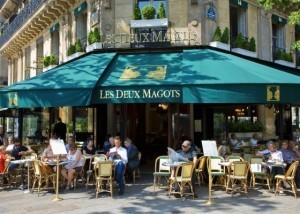

When I am changing a particularly pungent diaper, or worse, trying to wait out some inexplicable temper tantrum, I ask myself if I’d rather be sitting in a Parisian café with a cup of coffee, a croissant and an excellent book to read, or taking care of my sons. The answer, every time, is that I’d rather be right where I am—even if that means listening tone of my boys screech because I won’t let him dent up the kitchen table with his plastic triceratops.

I’ve discovered that pursuing my fantasies is the best way to dispel them. When I think through the implications of just dropping everything and going to France, even when I grant myself a superpower—instant teleportation—I regain my calm.

In my circumstances, if I’m alone with the boys it’s because my wife probably can’t be. So… what? The boys I love would be alone? My wife would need to take off work and sacrifice her own career? Or we’d need to hire a nanny? These options don’t work for me, or the people I love.

I think we often fail to grasp just how frequently, how constantly, we are making choices. We talk about feeling trapped but the truth is we are rarely “trapped” into anything. You’re never, and I mean this, never even stuck in traffic. A driver idling on a gridlocked road is entirely free to put the car in park (or not), exit the vehicle and start walking. If drivers tend to stay in their cars, it’s because they’re actively choosing this unyielding traffic and the ramifications of staying there over all that would happen if they walked away. Similarly, I could up and split the next time my kids are giving me trouble. I’ve got money in the bank and credit cards and a passport and could be on the next flight to Paris, if that’s what I actually wanted. The fact is, I prefer the consequences and pleasures of staying—the love, the sense of accomplishment—to the consequences and pleasures of leaving. And ever since I started looking at life this way, I bitch less. I’m probably also much better company.

December 29, 2014

Happy Happy Funk Funk

If I had the opportunity to interview Bruno Mars, I’d ask him how difficult it is to find his way to all this joy every time he performs. Imagine fighting through the flu, or a break-up, or a relative’s unwelcome medical diagnosis, to bring the happy with this much conviction and swagger.

[/youtube]

December 24, 2014

The Dad Files: What Happens When You’re Done Breastfeeding—But Your Wife Isn’t

The second time my wife developed mastitis, an infection related to breastfeeding, she sat there shivering on the couch, feverish and chilled, swearing repeatedly, “That’s it. I am so done! I’m weaning. Done. No more breastfeeding.”

I greeted the news cautiously, but after my wife spent the majority of the next 15 minutes dropping “f” bombs on the entire notion of breastfeeding, I chimed in.

“Do you mean it?” I asked. “Are you really done?”

“Hell yes,” she said. “I am sooo done.”

“Good,” I told her, “because I’m done, too.”

At the time, I believed she might actually have reached her breaking point. Her first bout with mastitis necessitated a four-day hospital stay; for months, she endured cracked and bleeding nipples and a stabbing pain that radiated across her entire breast. Every so often, if a few days passed without my seeing her grimace, I’d ask if the pain subsided.

At the time, I believed she might actually have reached her breaking point. Her first bout with mastitis necessitated a four-day hospital stay; for months, she endured cracked and bleeding nipples and a stabbing pain that radiated across her entire breast. Every so often, if a few days passed without my seeing her grimace, I’d ask if the pain subsided.

“No,” she’d say, “I’m still waiting for the good part.”

Of course, my wife chose to breastfeed because of the notable health benefits. But the “good part” held real, emotional allure: the bonding between mother and, in her case, twin sons; the joyful moments when the babies would look up at her and smile as they fed, milk dribbling down their precious chins. But now, her teeth chattering, the good part seemed a mere phantasm. And many of those studies on the health benefits associated with breastfeeding looked at children, like our boys, who had been breastfed for six months.

“Enough,” my wife said, “is enough.”

She seemed unequivocal. But even as I walked to the drugstore to pick up an antibiotic to fight her latest infection, I figured she’d probably change her mind. And sure enough, a couple of days later she started hedging.

“Have you talked to your lactation consultant about weaning?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said.

“What did she say?” I asked, afraid of her answer.

“She asked me if quitting breastfeeding is a decision I should be making at such a stressful time,” she replied.

My wife is usually expansive, elaborating on her answers in anticipation of any further questions. But now she was tight-lipped, like a hostile witness before a Senate committee.

“Did you say anything to her?” I prodded.

Lisa turned red. Her voice dropped several octaves. “I said I’d call back in a few days,” she admitted.

Now, I’d heard what it was like to attend a breastfeeding support-group meeting with this consultant. She led a discussion among all the moms in the room. And each woman who felt so inclined told her story and shared her problems. Invariably, some of the women there were encountering complications severe enough that they had to supplement their breastfeeding sessions with a bottle. Each time, those women received warm support from the entire group. But often, some woman had “made the transition,” successfully negotiating all the pitfalls of breastfeeding so that she could eliminate bottles entirely. And those women? Well, they received a big round of applause.

I started thinking of those support meetings as cultish. And I imagined this consultant, a woman I’ve never met, sitting in front of a big, colorful mural of a giant boob, the nipple dotted with milk, as cherubim circle around the areola, ready to feed. I mean, doing the best you can deserves support. But a woman resorts to a bottle—well, they’re not really applause worthy, are they?

A few days later, my wife explained that she was going to quit breastfeeding. Not now. And not in a month.

“I’m going to go as long as I can,” she said.

Now, I was of course plainly on the record as being done. And unlike my wife, I’d undergone no subsequent change of heart. So where did this leave me? Well, it left me just another guy with a list of grievances. My wife had become a Breast Nazi to a great enough degree that after I gave her this column to read she swore I got it all wrong. Pretty much. So, know that. But hey, they’re her boobs. And this is my column. So there.

What are my grievances?

Well, I could tell you that because she breastfeeds we don’t ever know how much food our boys are getting, and this can raise questions at naptime and every time we get them weighed. I could tell you breastfed babies wake more often in the night, meaning the whole thing with the breasts is robbing the entire family of sleep. And I could tell you that the threat of another infection is always there, and mastitis can be serious enough to require surgery. But, the truth is, just to be really selfish and personal for a second, I am just ready for her to put those things away: her breasts, I mean. I used to see them on what felt to me, every time, like a special occasion. Back then, the sight of them … served notice. But for the last six months, it is not unlike Mardi Gras at our house. By this I mean, boobs. Everywhere. And far from sex objects, my wife’s first set of twins are now hugely symbolic of our new responsibilities, individual and shared.

But the decision on when to quit breastfeeding remains my wife’s alone, and in spite of all I’ve written here, I wouldn’t have it any other way. In fact, the other night around 3 a.m., I watched her, eyes drooping, as the boys fed. They made little grunting noises at first. Then they made little lapping noises. And finally, they just breathed peacefully, in a steady rhythm. Our sons were, as my wife calls it, “dream eating”—sleeping, but continuing to eat automatically.

My wife softly stroked their heads, combing their hair with her fingers, and I noticed that, as has become their custom, the boys themselves were holding each other’s hands.

This, she tells me, is the good part, finally arrived.

A little too late for me. But I suppose, after how hard she fought to get here, my role is to be among those giving my wife a round of applause, even if I still have to get up in the middle of the night to do it.

What Happens When You’re Done Breastfeeding—But Your Wife Isn’t

The second time my wife developed mastitis, an infection related to breastfeeding, she sat there shivering on the couch, feverish and chilled, swearing repeatedly, “That’s it. I am so done! I’m weaning. Done. No more breastfeeding.”

I greeted the news cautiously, but after my wife spent the majority of the next 15 minutes dropping “f” bombs on the entire notion of breastfeeding, I chimed in.

“Do you mean it?” I asked. “Are you really done?”

“Hell yes,” she said. “I am sooo done.”

“Good,” I told her, “because I’m done, too.”

At the time, I believed she might actually have reached her breaking point. Her first bout with mastitis necessitated a four-day hospital stay; for months, she endured cracked and bleeding nipples and a stabbing pain that radiated across her entire breast. Every so often, if a few days passed without my seeing her grimace, I’d ask if the pain subsided.

At the time, I believed she might actually have reached her breaking point. Her first bout with mastitis necessitated a four-day hospital stay; for months, she endured cracked and bleeding nipples and a stabbing pain that radiated across her entire breast. Every so often, if a few days passed without my seeing her grimace, I’d ask if the pain subsided.

“No,” she’d say, “I’m still waiting for the good part.”

Of course, my wife chose to breastfeed because of the notable health benefits. But the “good part” held real, emotional allure: the bonding between mother and, in her case, twin sons; the joyful moments when the babies would look up at her and smile as they fed, milk dribbling down their precious chins. But now, her teeth chattering, the good part seemed a mere phantasm. And many of those studies on the health benefits associated with breastfeeding looked at children, like our boys, who had been breastfed for six months.

“Enough,” my wife said, “is enough.”

She seemed unequivocal. But even as I walked to the drugstore to pick up an antibiotic to fight her latest infection, I figured she’d probably change her mind. And sure enough, a couple of days later she started hedging.

“Have you talked to your lactation consultant about weaning?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said.

“What did she say?” I asked, afraid of her answer.

“She asked me if quitting breastfeeding is a decision I should be making at such a stressful time,” she replied.

My wife is usually expansive, elaborating on her answers in anticipation of any further questions. But now she was tight-lipped, like a hostile witness before a Senate committee.

“Did you say anything to her?” I prodded.

Lisa turned red. Her voice dropped several octaves. “I said I’d call back in a few days,” she admitted.

Now, I’d heard what it was like to attend a breastfeeding support-group meeting with this consultant. She led a discussion among all the moms in the room. And each woman who felt so inclined told her story and shared her problems. Invariably, some of the women there were encountering complications severe enough that they had to supplement their breastfeeding sessions with a bottle. Each time, those women received warm support from the entire group. But often, some woman had “made the transition,” successfully negotiating all the pitfalls of breastfeeding so that she could eliminate bottles entirely. And those women? Well, they received a big round of applause.

I started thinking of those support meetings as cultish. And I imagined this consultant, a woman I’ve never met, sitting in front of a big, colorful mural of a giant boob, the nipple dotted with milk, as cherubim circle around the areola, ready to feed. I mean, doing the best you can deserves support. But a woman resorts to a bottle—well, they’re not really applause worthy, are they?

A few days later, my wife explained that she was going to quit breastfeeding. Not now. And not in a month.

“I’m going to go as long as I can,” she said.

Now, I was of course plainly on the record as being done. And unlike my wife, I’d undergone no subsequent change of heart. So where did this leave me? Well, it left me just another guy with a list of grievances. My wife had become a Breast Nazi to a great enough degree that after I gave her this column to read she swore I got it all wrong. Pretty much. So, know that. But hey, they’re her boobs. And this is my column. So there.

What are my grievances?

Well, I could tell you that because she breastfeeds we don’t ever know how much food our boys are getting, and this can raise questions at naptime and every time we get them weighed. I could tell you breastfed babies wake more often in the night, meaning the whole thing with the breasts is robbing the entire family of sleep. And I could tell you that the threat of another infection is always there, and mastitis can be serious enough to require surgery. But, the truth is, just to be really selfish and personal for a second, I am just ready for her to put those things away: her breasts, I mean. I used to see them on what felt to me, every time, like a special occasion. Back then, the sight of them … served notice. But for the last six months, it is not unlike Mardi Gras at our house. By this I mean, boobs. Everywhere. And far from sex objects, my wife’s first set of twins are now hugely symbolic of our new responsibilities, individual and shared.

But the decision on when to quit breastfeeding remains my wife’s alone, and in spite of all I’ve written here, I wouldn’t have it any other way. In fact, the other night around 3 a.m., I watched her, eyes drooping, as the boys fed. They made little grunting noises at first. Then they made little lapping noises. And finally, they just breathed peacefully, in a steady rhythm. Our sons were, as my wife calls it, “dream eating”—sleeping, but continuing to eat automatically.

My wife softly stroked their heads, combing their hair with her fingers, and I noticed that, as has become their custom, the boys themselves were holding each other’s hands.

This, she tells me, is the good part, finally arrived.

A little too late for me. But I suppose, after how hard she fought to get here, my role is to be among those giving my wife a round of applause, even if I still have to get up in the middle of the night to do it.

November 13, 2014

The Dad Files: Don’t Do This

As a writer, I take it as a mark of pride to not only turn in well-researched and written copy, but to turn all that material in on the appointed deadline. I’ve been working as a professional journalist for 17 years. The people I’ve seen wash out of the business or simply leave too much wreckage in their wake didn’t respect deadlines or the time and efforts of the staff—editors, copy editors, fact checkers, the art department—that make any publication go.

As a writer, I take it as a mark of pride to not only turn in well-researched and written copy, but to turn all that material in on the appointed deadline. I’ve been working as a professional journalist for 17 years. The people I’ve seen wash out of the business or simply leave too much wreckage in their wake didn’t respect deadlines or the time and efforts of the staff—editors, copy editors, fact checkers, the art department—that make any publication go.

If a writer is assigned a story at 5,000 words, that is due on, say, December 15th, that writer can best prove their professionalism by turning the piece in very near that word count and on or before the given date. Deviations from the agreed-upon story, its length and due date must be communicated ASAP. I mention all this so you’ll understand how odd the following story is, both within my career and in journalism as a whole.

In October, 2011, Discover Magazine assigned me to write a story about Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz, a neuropsychiatrist and an expert in “self-directed neuroplasticity.” The adult human brain was long thought to be fixed. Schwartz proved not only that it could change its shape and function but that we could “self-direct” or will these changes. The story, as I remember it, was due in February 2012, at a length of 5,000 words. But my wife was pregnant at the time with our twins and the obligations I had—from prepping for the babies, to promoting my book Fringe-ology and maintaining my role at Philadelphia— forced me to keep pushing back the delivery date.

At one point, after I wrote a first draft of maybe 7,000 words that I could not seem to chop down any further. I called my editor, a terrific, veteran wordsmith, and told her about my struggles.

She told me I could turn the story in at 6,000 words. I did. She didn’t like it, and neither did I.

“This happens to everyone who writes for us,” she said. “Synthesizing all of this science, making the reader feel like they are peering over a great scientist’s shoulder as he works, this isn’t easy.”

She made a single, sound structural suggestion—namely, that I needed to stick to a strict, chronological sequencing of events–and sent me on my way. I probably hung up feeling worse than I ever had in my career. I had tried to get the story to her ahead of the birth of my twins, knowing that my life was about to be reconstructed in ways I couldn’t fully predict. My experience told me that when an editor offers such a brief critique, with an admonition that is purely about the structure of the story, I essentially had to start over. My first draft wasn’t even close.

Some time shortly after that, the boys were born, and I could barely function. They ate every 2:30 to 3 hours, all day and all night. They required supplemental bottle feedings. For the first four to five months of their lives, I got just three intervals of sleep each night, ranging from 45 minutes to 1 hour in length. Otherwise, I tended to my wife, washed bottles, prepared food, and tried, for eight hours a day, to act like I was still holding my work life together. At least three times I walked to my office, at 18th and Market Street in Philadelphia, closed the door, and cried.

I feared for my own survival, as well as that of my new twin sons. That might sound melodramatic. But sleep deprivation has a way of heightening emotions associated with anxiety, anger and fear. The Discover story manuscript sat, unopened, on my computer hard drive, for more than six months. Money was tight with these expensive little babies in the mix. We could of used an influx of cash. But I lacked the time, energy or emotional clarity to even get started.

As I remember it, it was winter, 2013, before our lives settled down enough that I could carve out a stretch of three workdays—a weekend with a Monday holiday—to try my hand at recasting that story. I left the boys with my wife, Lisa, and relatives, and set out to find some public space in which to write.

I had decided, at this point, to treat this second draft like a first attempt. Without regard for length, or even quality, I was simply going to sit down and write the story in chronological order.

I also decided to work in a rather famous little Philadelphia dive bar, McGlinchey’s, thinking the smoky, active atmosphere—not to mention a couple of beers—might loosen me up. For three days, I worked there from a ratty booth, putting in shifts of five or six hours, writing through Schwartz’s career as fast as I could. I ignored the word count, writing in a text format that didn’t display one. When I finished, I knew there would be a lot of work to do, refining or rewriting every sentence. Yet I had a feeling of completeness I only get when I connected with the material.

I came home, reported success and told my wife I would need the following weekend to carry out a rewrite.

That time, for two days, I worked longer hours, and from home. I sat upstairs in my bedroom office, wearing headphones that played classical music and tried to get each scene, each sentence, right. As I neared the end, after maybe 16 hours of effort, I felt very good about what I’d achieved—good enough, even, that I packed up my laptop and headed back to McGlinchey’s. My thought was that I would finish the piece and email it from the bar where I found the stroke this piece required—and where I’d realized that life, after twins, could still include time for the work I’ve always enjoyed.

I ordered a beer, re-read the story from first word to last and made very few changes. The deadline I’d originally been given was long past, the assignment more than a year old, but it was finished. I had, by this time, still not looked at the word count. I figured it was around 7,000 words.

Feeling good, maybe a little buzzed by then with a second beer in me, I went ahead and looked. Clicking on the toolbar, I selected “word count.”

A second later my buzz was gone: The computer spat the total out at me: 14,721 words.

I gasped. I felt sick. And then, well, I laughed. I scrolled through the piece, back and forth, multiple times, for any whole scenes that might be unnecessary. Then I thought about how hard the last year had been. I thought about how desperately I longed to be finished with this piece. And I hatched what—looking back—was a rather naïve if not stupid and disrespectful plan.

“Ah, screw it,” I thought.

I figured I’d send the story in, at its current length, and if they didn’t like it—well, I would just release it myself, through Amazon or some website, in e-single form. The length was just write for a growing pile of stories published at Byliner, the Atavist and Longform. I opened an email, put in the address of my editor, Pam Weintraub, and started to write a note apologizing for its length. Then I stopped.

“Screw it,” I thought again, and this time I even said it out loud. Then I attached the file and hit “send.”

I thought my relationship with Discover might very well be over. A few days later, when my phone rang and Pam came up on my caller ID, I figured this was it, her very well-deserved chance to tear me apart for my lack of professionalism. I had, at this point, broken every rule I could think of, turning in a story more than a year past its original deadline, at 270-percent of its contracted length. “As you can imagine,” she began, “when I opened the file the first thing I did was look at the word count. And when I saw what it was, I was in shock. But I read the lede, and I just kept reading, and I loved it.”

Discover subsequently published the piece as an e-single, and our relationship continues. I recently turned in another piece, which they project for an April 2015 pub date. I feel grateful, however, that Pam even read the lede. A lot of editors would have just closed the file and written me off. In purely professional terms, they would have been justified. But this story was meant to be—and meant, I believe, to be long.

November 10, 2014

The Best Bands You Never Heard Of

I saw Donkey perform in the mid-90s, at the Covered Dish, in Gainesville, Fla., when the music scene surrounding the University of Florida was booming with great music, like For Squirrels, Big White Undies and Bloom.

Donkey, from Atlanta, came in carrying its own flag—a swaggering, jazzy balladry that, well—that had that swing. I can’t remember if I was working the door that night or just a customer. I do know that I loved the band’s whole shtick. Over the years, I’ve played their album, Slick Night Out, from time to time, and continued to be amazed at how fresh it still sounds. The other day, when they came up on shuffle, I decided to kick around the Internet for a minute to see what became of them. Turns out they reunited over the summer. You can see that performance here, but this is a pretty cheaply produced video of the band playing “Never Too Late To Mend,” from around the time they played in Gainesville.

Click here to view the video on YouTube.

November 3, 2014

Writer Tony Rehagen: The Generalist Interview

I met Tony Rehagen at a conference in Atlanta, in 2013, when he was nominated for Writer of the Year at the City and Regional Magazine Awards. I first saw him as he is here, playing guitar.

I met Tony Rehagen at a conference in Atlanta, in 2013, when he was nominated for Writer of the Year at the City and Regional Magazine Awards. I first saw him as he is here, playing guitar.

I didn’t know what I was walking into when I arrived. Rehagen’s friend, fellow writer Justin Heckert, had urged me to come to a house party, where it turned out pretty much everyone but me had come prepared to sing.

I heard a lot of great music that night, played by a lot of great writers. In addition to Rehagen and Heckert, Thomas Lake was there, as well as the novelist Charles McNair. And when I remember that night I think mostly about the relationship I felt between their singing and their work. Every moment seemed an act of creation, and Rehagen was one of the stalwarts. He sang and when others took a turn at lead vocals he supported them with his guitar.

By that time I’d read his award nominated stories and already counted myself as a fan. Rehagen’s great strength, it seems to me, is adapting his voice to his material. For the sake of this interview, I asked him to send me a few stories to use as a jumping off point to talk about writing in specific and the magazine business in general. The three stories he chose are incredibly varied in tone.

“The Crossing” is spare and muscular, like something I’d imagine Cormac McCarthy producing if he lit off after a true story about trains: Some death, an existential dread, the creeping sense that everything isn’t going to be all right.

My favorite of the three is “This Land Is My Land,” which is perfect from its well-chosen title to its inevitable, crushing end. I think of it as the nonfiction equivalent of some dusty tune by The Band, capturing the romantic myth of what it means to own—a house, land, a legacy—and the dangers of wanting too much.

I was pleasantly surprised when Rehagen sent me “Re: Fredi,” which is light—jeez, it’s about baseball—in comparison to the other articles he chose. The fun here is Rehagen’s novel structure—a one-sided email exchange between him, and his editor.

The Generalist: Let’s start with some introductions. You’re a University of Missouri J School grad. Tell me something about that experience, please. When did you know you wanted to be a writer? Give me your origin story…

Rehagen: I totally fell into this profession. I set out to be a musician, played in bands all through high school and college. I liked to write and was at MU so I figured journalism would be a fit for a degree. I liked sports and started there, with zero experience. The first story I ever wrote was a volleyball preview. Along the way, I fell in with a group of classmates and fellow sports writers (especially Daimon Eklund, Justin Heckert, Wright Thompson, Steve Walentik, and Seth Wickersham) who introduced me to the work of Gary Smith and Tom Junod and Michael Paterniti. The guys in that little Mizzou sportswriting cabal were just a bunch of writing junkies—talented junkies who inspired me, and continue to inspire me. But I burnt out on J-school. I took a break after graduation and played music. After a year or so, I was married and had to start making money, and I had this journalism degree, so I went to work for this small-town weekly newspaper where I could write what I wanted and as much as I wanted. The fire was just reignited.

The Generalist: So, let’s talk about these three stories on the docket, beginning with “The Crossing.” I imagine you read about the circumstances in the paper. I pulled a few of the briefs. They all run along pretty much the same line: “Man killed by train while trying to rescue crash victim.” These are 200 word stories, but you saw something else there. How did you come across this, and what made you decide it was a bigger story?

Rehagen: I did see it in the paper, and it immediately struck me that there was something profound there. I mean, the idea that these three characters—two complete strangers and the train—would arrive at the same place at the same time and their courses were forever altered because of it…I knew I wanted to explore it.

The Generalist: Can you tell me anything about the pitch process? The seeming waste—a 48-year old man dies trying to save an octogenarian with bone cancer—isn’t a sexy story. It’s pretty brutal. Was it a hard sell?

Rehagen: There was no pitch. My editor, Steve Fennessy, saw the same story and had the same idea, the same sense that there was something deeper there. He brought it up to me before I had a chance to pitch it.

The Generalist: That in itself is remarkable. A story like that could be so easily passed over without much consideration. I’d add this, too: This piece ran five months after the men involved died. And as a reader, I don’t think I learn anything more—not a single detail— about Atlanta by reading it. But as a person, I feel like I was put in direct touch with the precariousness and seeming unfairness of life. I think a common problem at city and regional magazines is to be so caught up in connecting people to the area they live that we can forget that a universal story, as I’d suggest this is, is still worth sharing with “local” readers. I’m curious if there was any discussion about whether the story had enough to do with Atlanta.

Rehagen: Well, one thing that makes it very Atlanta is the train. I mean this is a railroad town, founded as “terminus,” and the rails are still a major, if overlooked, presence throughout the city. Reporting this story, I also discovered a pretty significant subculture of trainspotters who collect photos and videos of trains. (In fact, I found one spotter who had taped this very train just fifteen minutes or so before it hit Dekai—that’s where I got the details of the train in the last section.) But your point is valid. Fortunately, I have an editor who wants those universal stories. He lets me travel the entire state to find them. But, of course, he’d prefer I find them in the city casting reflections on what’s going on here at the moment.

The Generalist: You know, as a Yankee, and a writer, I probably romanticize the South and its story telling culture. When I saw that this story ran at all it struck me as being of a piece with my image of the South, anyway, as a place that understands that the value of a good yarn—complete with hard, life and death themes—transcends anything so temporary as “news.” Is there any truth in that admittedly shopworn image of the South I’m carrying around?

Rehagen: Well, Missouri, especially Mid-Mo, where I’m from and went to school, isn’t exactly the South. It’s this weird border-state nether region that had plenty of people fighting on both sides of the Civil War. So moving down here from Indiana (which I found to be more like Mid-Missouri than North Georgia), I had the same romantic notion of the stories of the South. I’ve indulged that notion, written about moonshiners, land feuds, alligator hunting, peach farmers, and cotton mills during the War Between the States. But I think there is a special esteem bestowed on writers down here. And I always joke that the warmer climate makes people a little more stir-crazy (or just plain crazy), yielding more fascinating stories. That’s why my journalist friends in Florida are neck-deep in bizarre, compelling material.

The Generalist: I admired the story, in the end, for how poetic the language is and how spare—just over 2,400 words and nothin’ extra. Can you talk to me, a little, about the writing process? I’m assuming your target was the 2,500-word bin of the feature well. Was that tough to do on this?

Rehagen: I didn’t set out with any parameters of length. In fact the first draft, which was told chronologically, was around 4,000 words. But it wasn’t working, too much backstory on the two men, it took too long to get to what made the story special (the actual crossing). So my editor, Steve Fennessy, suggested I try telling it backwards, unpacking the backstory quickly through the scenes. And it worked, I think. But with the climax now appearing so close to the front, I felt I had to get out of the piece as quickly as possible before readers lost interest. So the 2,400-word total was more the byproduct than the goal.

The Generalist: I find that fascinating. I’ve generally worked in places where the range, in terms of word count, can be pretty rigid. The word count can be very generous, maybe 5,000 words, but as the writer you’re then duty bound to give them something within five hundred words of that, give or take. Are you usually able to sit down and write the story as long as it needs to be, without too much care for its length?

Rehagen: Usually, the same thing applies to me here. My editor drills me on tightening. A 5,000-word piece would be the exception. And I usually write well over that limit and try to cut it back within range. But in this case, my editor seemed open to what form it could ultimately take, and he gave me time and encouragement to play around with it.

The Generalist: I told you, about a year ago, that I thought “This Land Is My Land” is one of the best stories I’ve read in recent years, sprawling and epic. It’s not just the generous size, a shade under 6,000 words, but the various themes involved in this story, a land dispute that resulted in murder. Before I gush too much more, please tell me a little bit about how you found this story.

Rehagen: This story was actually waiting for me when I arrived at Atlanta magazine in August 2011. Fennessy had found this in the local newspaper (a story that didn’t quote either side). He had assigned it to two previous (and incredible) writers, dear friends Thomas Lake (now of Sports Illustrated) and Justin Heckert (Esquire, New York Times Magazine, etc), but both left the mag before getting to work on it. I had heard Heckert talk about it and I was instantly jealous, so I was elated to inherit the idea. I mean, this story had everything: Land feud, a guns dealer and moonshiner…in the North Georgia Mountains! Writes itself.

The Generalist: The piece deals in a lot of history, dating back to how land was allotted to whites in 1832, in a Gold Lottery that drove the Cherokee tribe westward on the Trail of Tears. From there you chronicle how the boundaries surrounding these properties, once clearly defined, became confused. “Into the 1950s, owners would sell a land lot of forty acres, ‘more or less,’ even if the actual lines had long been blurred, moved, or skewed, or if parts of the original square lot had been broken off and weren’t technically theirs to unload. …Meanwhile fences went up, gradually becoming accepted boundaries—whether they ran along actual property lines or not.”

The section is just so richly detailed. You write, “…surveyors would enter dubious landmarks such as ‘rock piles’ and ‘big trees’ into the deed descriptions.”

Please tell me a little bit about your research process here—how you got the information, and how happy did you feel when it turned out that land surveying is so fascinating.

Rehagen: While I was first thinking about this story I went to see the movie Prometheus. The movie was a disappointment, but when the humans are first landing on the alien world and see the structures lined up, the lead scientist says, “God does not create in straight lines.” It hit me: This story was about lines (I even co-opted the spirit of that line with “There are no straight lines in nature.”) So I started researching the history of that land in books and online. But the actual surveying didn’t come until I got into the legal documents of this specific case. There were volumes of deeds and sales and maps and surveys and it didn’t make any sense to me. I started talking to area surveyors who spoke generally about this situation and even one guy who had dealt with Dempsey previously. But when I finally got ahold of Webb, the surveyor who did the last survey for Dempsey, it all came together. It clicked. He just explained it all in a way that was interesting and funny and made sense. He had one of my all-time favorite quotes: “I once came across a property line described as ‘Two smokes on a mule’s back from the chestnut stump,’” says Richard Webb, who in thirty-six years as a surveyor in North Georgia has dug through volumes of yellowed maps and deeds. “Well, how big was the mule? And what were you smoking?”

The Generalist: Tell me about the process of learning about these two main characters, Jewell Crane and Lewis Dempsey. What kind of cooperation did you get from interview subjects, in capturing the history of these men and their families, and how did you gain it?

Rehagen: In the rarest of rare instances, I got full cooperation from both sides. Both families felt that they had been given a raw deal. Dempsey swore he was innocent, that he had acted in self-defense and felt he’d been denied his day to prove it in court. The Cranes obviously felt cheated out of justice for their dead patriarch. All I had to do was tell them that I wanted to get their sides of the story out and hit record.

The Generalist: That’s pretty special right there. Did the two sides lobby you much, or worse, ask you whose side you were taking? I’ve certainly covered disputes before where, at the end of the interview process, before I’ve written, the protagonists want to know if they won me over.

Rehagen: The Crane side didn’t seem overly concerned with my stance. They seemed very confident that they were clearly wronged by Dempsey and the courts. They’re the ones who lost a patriarch. Dempsey, on the other hand, was constantly pushing me to see his side, pleading his case. But he seemed sincere. After all, because he didn’t get his day in court, I was the closest he could come to judge and jury in his mind.

The Generalist: Without giving away anything of your ending, the point of tension is that Dempsey believes he has a claim on what had commonly been considered Crane land, some of which was used by the Cranes to grow corn. But of course it turns out that the land is symbolic—not the real issue in the dispute between these men. Is that something you already knew, or expected, when you started in on this story or found in the course of your research?

Rehagen: It hit me when I went out to personally walk the land in dispute. It was just a few hundred square feet of mostly steep, rocky hillside. Mostly worthless. The area with corn was miniscule. So I knew the argument had to be about something deeper. Besides, from all accounts the families, even Dempsey and Crane, had gotten along for years before their falling out.

The Generalist: Let’s talk about the writing here. How’d this one come together? How many drafts? The story, as it progresses, is true Americana. If The Band split up and started writing nonfiction feature stories, they’d have done this piece. Did you have any sense yourself, when you sat down to write, that you had something special on your hands?

Rehagen: This one came out pretty smooth. I knew I had a story that I, the writer, could only fuck up, so I was determined not to get in the way. I wanted it to read like a David Grann story. I had two editors (Lake and Fennessy). Lake tweaked the lede, suggested combining my second and third sections into the second section that ran, and did a tight, tight overall line edit really firming up the language. On the second draft, Fennessy had a few good suggestions and questions. And that was pretty much it. What you see is very recognizable from the first draft.

The Generalist: Yeah, I would imagine a lot of writers picked up on this sentiment when you joked earlier, that the story “writes itself.” I find that moment, when I realize the material is so strong that I need to work, mostly, not to diminish it, to be one of the most humbling for me.

Do you relate to that feeling, in stories other than this one? I hate to say it because of course I’d like to think I’m capable of moving readers with a well-constructed sentence but I think I get my best results when I get out of the way.

Rehagen: I always feel that way. That’s why I’ve come to believe the story idea is the most crucial part of what we do. Great idea trumps great writer every time. (Of course, there’s no reason these two have to be mutually exclusive.) And that’s the part of my game that I’m really trying to improve upon—identifying great ideas and sussing out the best approach, which, if the idea is really good, is usually the simplest one.

The Generalist: Finally, “Re: Fredi” is in such a different mold. The whole piece is a series of emails from you to your editor there at Atlanta, pitching him on the very story we’re reading. It’s deliciously meta but of course I have to ask how many of the emails in the story did you actually send?

Rehagen: All of the emails were written anew for the story. The first section is not too far off from the essence of the pitch email I sent. That email was not nearly as detailed (or well thought out). But the premise is absolutely true. Fennessy would constantly complain about Fredi and I finally pitched him a story proving him wrong, which he greenlit.

The Generalist: How did you guys settle on this incredible, novel structure?

Rehagen: This is another story where I had Lake and Fennessy as editors. The “pitch” idea was first thrown out by Lake, but I was reluctant, thinking that my outsider status weakened my argument. So I wrote a traditional profile of Fredi and Lake and I worked it into a draft for Fennessy. Fredi wasn’t very accessible. The story was okay—not very special. After a first read, Fennessy, completely independent of what Lake had said, mentioned the idea of a story pitch format—and he convinced me that my outsider status would actually be a strength. Fennessy volunteered to try a back and forth, but after I dove into it, I felt it’d be fine with just my side of the correspondence—and as an extra, tongue-in-cheek on non-responsive editors that you and other freelancers will get immediately.

The Generalist: And what kind of response did the story receive?

Rehagen: Very positive from Braves fans on Twitter. But other than that, very little response. When it came out, the Braves were doing well, off to a hot start. Besides, Atlanta is notorious for being a rather apathetic sports town (although the Braves can be the exception, especially to fans outside the city).

The Generalist: Did you feel hemmed in by the “email” structure at any point?

Rehagen: It was a little cumbersome trying to work in my sourcing as if I had just casually talked with them (ie Chipper Jones told me…) But other than that it was a pretty natural and quick rewrite. I mean the idea from the start was a baseball-centric argument for why this guy was actually a good manager. The email format actually freed me to ignore all the profile conventions and just lay out my argument. I got to type out entire grafs and sections of stuff that I had used talking over the story with Lake and Fennessy that didn’t fit into the original, traditional format.

The Generalist: Can you tell me a little bit about your writing process? Do you sit down and do a read through of all your notes before you write? Do you outline the story before beginning? Do you write in the office, or at home? Is there a particular time of day when you’re most productive/creative as a writer? Do you ever listen to music as you write? Do you need silence?… Do you generally set aside a specific number of days to write a draft of any given story? These questions might sound picayune, but I’m fascinated by how other writers go about even the physical process of the job. Feel free to answer them all at once with a general description of how you get the work of writing finished.

Rehagen: Sometimes I read through my notes, but the best stories are those I just dive into and then refer back to my notes later. I’ve only started outlining in the last couple years, and it’s been a godsend. Turns out I’m a very detailed outliner and the preorganization of information has made it so much easier to write that first draft (although that is still my least favorite part of the job). I write both at home and the office, though usually each story lives in one place or the other, if for no other reason than because all my notes and materials reside there. I’m much more productive in the morning or late at night. Most of what I write after 3 pm will need to be rewritten. When I’m at home, I rely on a good run at lunch to help me mentally sort out my last push in the early afternoon. Sometimes I listen to music (always classical or movie scores Hans Zimmer, James Horner, etc.—no lyrics) that I can associate with the tone I want in the story. But when I’m really struggling, only silence (or the white noise of a newsroom) will do. I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m good for about 750-800 good words a day. Sometimes I’ll get more out, if need be. But I’ll rewrite them that night or the next morning.

The Generalist: This question is a bit of a shot in the dark but you’re a musician and I wonder to what degree, if any, music influences your writing. Do you ever find yourself thinking, ‘This story needs to read like this piece/this album/this band sounds?’ I think of writing this sort of nonfiction as likely coming from a similar place as any creative endeavor, including music…

Rehagen: If there’s a connection between the rhythm of the language and my built-in musical metronome, it’s totally subconscious. But I certainly draw inspiration of tone from songs and albums. I remember thinking that I wanted “This Land Is My Land” to have the same feel as the song “Decoration Day” by the Drive-by Truckers. I remember listening to Christopher Young’s score to the movie of The Shipping News while writing a story about spending two days on a shrimping boat. So there’s definitely a connection.

The Generalist: Lastly, is there one piece of advice on reporting or writing that anyone’s given you, or any specific lessons you’ve learned, that you’d like to pass on to your brethren?

Rehagen: Never close yourself off from criticism. I think you have to have a healthy ego to put yourself out there like we do, and ultimately, you have to know deep down whether your work is as good as it can be. But I don’t think it’s good to ever get to the point where you think you know it all. And when I say criticism, I mean not only from editors and fellow writers, but from readers. “Don’t read the comments” has become a mantra for writers, but I think you should always read the comments. Granted, I don’t get as many comments as some writers. And yes, 95 percent of them will range from uniformed to baseless to irrelevant to batshit crazy. But lost in that sewage can be a comment that helps you see things differently and that you might be able to learn from.

October 30, 2014

The Legacy of Jack Wheeler

I’ve been thinking a lot, of late, about John Parsons Wheeler III. Wheeler was a driving force for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, one of the most visited sites in all of America. His murder, almost four years ago, received international attention. His death has been ruled a homicide, by blunt force trauma, a category that covers assaults by an object, like a baseball bat, or a fist. Other than this ruling, however, we seem no closer to an answer now than we did when his body was first discovered.

I’ve been thinking a lot, of late, about John Parsons Wheeler III. Wheeler was a driving force for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, one of the most visited sites in all of America. His murder, almost four years ago, received international attention. His death has been ruled a homicide, by blunt force trauma, a category that covers assaults by an object, like a baseball bat, or a fist. Other than this ruling, however, we seem no closer to an answer now than we did when his body was first discovered.

The mystery is perplexing. But I’ve been thinking about Wheeler for this and other reasons. A West Point grad, Wheeler served as a soldier in Vietnam. He was a driving force behind the Veterans Memorial. He worked as chairman and CEO of Mother’s Against Drunk Driving, helping to push them to prominence; and as President of the Deafness Research Foundation, where he battled to make tests for deafness in infants standard. He pushed to create effective, modernized schools in Vietnam, through his leadership of the Vietnam Children’s Fund, and sought reconciliation with the country where he served and many of his classmates died in war.

A spiritual man, Wheeler also spoke to friends and family at times about the notion of “grace.” In theology, grace is usually described as a kind of gift that God bestows upon us, not because we deserve it but simply because he desires us to have it.

In the years after Wheeler succeeded in efforts to see the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—“The Wall”—built, stories cropped up of veterans finding each other there after years without contact. Others might hear these stories and think of them as fortunate coincidences. What were the chances that former war buddies, from different parts of the country, would choose to turn up there on the same day and time? Wheeler referred to these coincidences as examples of “grace.”

I remember reading, many years ago, in an interview I can’t seem to find now, the rock singer Bono’s lament that we willingly share intimate details of our lives to friends over dinner, yet if someone mentions the word “grace” everyone will feel embarrassed. Notions of spirit, of religious belief, aren’t just personal. They also seem to risk triggering interpersonal versions of the larger cultural war in play between high-profile atheists and believers. In this milieu, the very idea of something like grace becomes ghettoized. However, I think that Wheeler left behind a sense of grace that lives on after his murder and sits apart from the mystery surrounding his death. The Wall he helped create was a great source of healing for the entire country after the Vietnam War. MADD likely saved many millions of lives with its campaign to stop drunk driving. Many adults can hear, today, became of the work he did with the Deafness Research Foundation. And schools he helped imagine and fundraise for, in Vietnam, are still being built today. His murder remains unsolved. Yet the work he did still touches people, most of whom probably don’t know of the role he played in bettering their lives.

In theological terms, I don’t suppose that the sort of afterlife evident in the story of Jack Wheeler qualifies as grace. However, I think of it as related—a gift people have received, from a man they can’t see.

Steve Volk's Blog

- Steve Volk's profile

- 18 followers