Tariq Ali's Blog, page 5

July 7, 2015

The Syriza Triumph is a Victory – on Greece and the OXI vote

This a historic triumph for Greece, its people and democratic accountability. The disgusting campaign waged by the EU Group and ECB has backfired sensationally. The invertebrate Greek politicians who voted YES misjudged the mood of their people. The EU leaders who waged a financial war on Greece should look in the mirror. If what they see is ugly, they should not blame the mirror. The Syriza triumph is a victory. How should it be interpreted? A slap in the face of the EU elite and the Troika; a signal that people are ahead of the politicians and prepared to go further. They have seen their government pleading, begging on its knees for an agreement. They have seen SYRIZA abandon its programme and their response is don’t go any further. Take a tougher position. Don’t capitulate. Fight back. We are with you. The minute Tsipras decided to go for a referendum, the mass movement was revived. ?

The questions that arise immediately are the following:

?If there is no serious agreement on any meaningful debt restructuring is the government prepared to default? If the EU stance remains the same is SYRIZA prepared to quit the Eurozone and implement Plan B?

?I hope so. The Greek negotiators now know that their people will support them further if they are told the truth. That is what Tsipras did at the historic Syntagma mass demonstration last week and we have the response. The Greek people have reasserted their sovereignty. Their government must now do the same.

June 30, 2015

We are witnessing the twilight of democracy

Instead of worrying too much about the extreme left and right, we should focus more on the extreme center, says writer Tariq Ali. He spoke to Creston Davis about the decline of democracy and German hegemony in Europe.

Creston Davis: Mr. Ali, with regards to your most recent book, The Extreme Center: A Warning, what are the characteristics that define extremism in your opinion?

Tariq Ali: For one, continuous wars—which we have now had since 2001—starting with Afghanistan, continuing on to Iraq. And even since Iraq, it’s been more or less continuous. The appalling war in Libya, which has wrecked that country and wrecked that part of the world, and which isn’t over by any means. The indirect Western intervention in Syria, which has created new monsters. These are policies, which if carried out by any individual government, would be considered extremist. Now, they’re being carried out collectively by the United States, backed by some of the countries of the European Union. So that is the first extremism. The second extremism is the unremitting assault on ordinary people, citizens inside European and North American states, by a capitalist system which is rapacious, blind, and concerned with only one thing: making money and enhancing the profits of the 1%. So I would say that these two are the central pillars of the extreme center. Add to that the level of surveillance and new laws which have been put on the statute books of most countries: the imprisonment of people without trial for long periods, torture, its justification, etc.

Davis: Normally we think of extremes on the far right and the far left. In this case, you are articulating an extreme of the center. How did you arrive at that analysis?

Ali: Well, I was giving a talk and in response to a question on the extreme left and the extreme right, I said that while these forces exist, they’re not very strong—through the extreme right is getting stronger. I observed that the reason the extreme right is getting stronger is because of the extreme center, and then I explained it. So that’s how the idea developed. The people at the talk were interested, and so I developed it further and thought about it over the next months. Many people were intrigued by it, and so I sat down and wrote this little book.

Davis: The book also addresses the “suicide of Western politics.” What are the basic elements of that?

Ali: It’s not just politics. Basically, we are witnessing the twilight of democracy. I’m not the first to say it, and I won’t be the last. Others have dealt with the issue. Peter Mair—alas no longer with us—who used to teach at the European University, wrote a book for instance which was published posthumously. Also the German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck, who has been mapping what has been happening to democracy in the European Union and elsewhere. I’ve developed from some of these people’s writings the idea that the extreme center is the political expression of the neoliberal state. That economics and politics are so intertwined and interlinked that politics now, mainstream politics, extreme center politics, are little else but a version of concentrated economics. And this means that any alternative—alternative capitalism, left Keynesianism, intervention by the state to help the poor, rolling back the privatizations—becomes a huge issue. The entire weight of the extreme center and its media is turned against it, which in reality now is beginning to harm democracy.

Davis: Do you think there is hope in the rise of Syriza, Podemos, Sinn Féin and other Left political parties?

Ali: Well, I think Syriza and Podemos are very, very different from Sinn Féin in many ways, and so I wouldn’t put all three together. I would say that Syriza and Podemos are movements which have come out of mass struggles. In the case of Podemos, directly out of huge mass movements in Spain, which started with the occupation of the square. In Greece, as a response to what the EU was doing there, punishing it endlessly, for the sins of its ruling elite. And so the response of the people was finally to elect the Syriza government to take on the Troika and set them up with a new alternative. Its future will depend very much on whether they’re able to do so or not.

Davis: Do you think they will?

Ali: At the moment we have a critical situation in Greece. Even as we speak, where there is an open attempt by the EU to destroy Syriza by splitting it. There is a German obstinacy and utter refusal to seriously consider an alternative. The reason isn’t even a lack of money, because money swims around the EU coffers endlessly, and they could write off the debt tomorrow if they wanted. But they don’t want to do so, because of the election of a left-wing government. They want to punish Syriza in public, to humiliate it so that this model doesn’t go any further than Greece. We are seeing a struggle between the Syriza government and the Troika—as well as the American side, the IMF—with very little room for any compromise. In my opinion, Syriza has already gone too far.

Davis: What would the latter choice look like?

Ali: They could just say, “No, this is not a debt which has been incurred by the Greek people. This is a debt incurred by the elite, and the reason this debt has mounted is because our books were not in order when we were let into the Euro currency, and the Germans knew that. The whole of Europe knew that.” They could refuse to pay and chart a new course. Whether they can do this on their own without the support of the Greek people is a moot point.

Davis: How has the idea of economics hijacking politics played out in the European Union more generally?

Ali: The European Union is a union of the extreme center. It’s a banker’s union. You see how they operate in country after country, appointing technocrats to take over and run countries for long periods. They did it in Greece; they did it in Italy; they considered it in other parts of Europe. So it’s effectively a union dominated by the German political and economic elite. Its main function is to serve as a nucleus for financial capitalism and to ease the road for that capitalism. The other functions just irritate everyone: it’s undemocratic; decisions are not made by parliament; the European Parliament is not sovereign. How could it be when Europe is divided into so many different states? The decisions are all made by the representatives of the different members of the European Union, i.e. the governments of Europe, which are extreme center governments in most cases. And so, the European Union has lost virtually all of its credibility amongst large swaths of the European population. In recent election in Britain for instance, the big point of debate—among a few others—between the Labour and Conservative parties was whether or not to have a referendum on Europe, whether or not to allow people to state their choice, to vote on how they feel in relation to Europe.

Davis: And in other parts of Europe?

Ali: Effectively, the EU is a very powerful bureaucracy, dominated now by the German elite, which is backed by the rest of the European Union members. If you go to former Yugoslav states, the Balkan states, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia, the situation is dire. Not to mention Bosnia, which is just run like a colony. The way they used to stand up and sing hymns to President Tito, they now salute the EU flag. It’s a very strange transition that we’re witnessing in most of Europe, and I don’t think it’s going to work. I think another crisis, which is being predicted now and which will be worse than what we saw in 2008, could bring the European Union down unless there are huge reforms from within to democratize, to give more power to the regions, etc. If this doesn’t happen, the European Union will fall.

Davis: Many intellectuals here in Athens agree with you that the EU is backed by the German elite. Some even go as far as to say that it’s Germany trying to take control of Europe once again.

Ali: I know this argument. It’s not invisible. It’s there for everyone to see. But I think to compare it to the Third Reich is utterly ludicrous. Germany is a capitalist state nurtured carefully and brought back to prosperity by the United States, and it is very loyal to the United States. I don’t even think the Germans enjoy full sovereignty. There are some things which they cannot do if the United States doesn’t wish them to do it. So, one cannot discuss Europe without understanding US imperial hegemony, both globally and certainly in Europe as it stands. It’s an alliance that the Americans control, in which the EU of course has a great deal of autonomy, but in which it still is very dependent on the United States, especially militarily, but not only in that respect. So to blame the Germans for everything is an easy way out for some of those suffering in Europe today. At the time of German Reunification, it was no secret that Germany would soon become the strongest political entity in the European Union. And that has happened.

Davis: So it was inevitable that Germany would act this way?

Ali: Any country in that position would exert its authority. The real problem is the total capitulation of German social democracy to capitalism, reflected and symbolized by actual extreme center coalition governments in Germany, which have been in power for a long time and still are even as we speak. That is the real problem: that there is no serious opposition in Germany at all. And the Left party is divided. There are huge political problems in that country, but German economic power is something which was bound to happen. The way out of this situation is through the further democratization of the European Union and a changing of its structures. The current Eurozone is obviously dysfunctional. And serious people within Germany and elsewhere know this to be the case and know things cannot function this way forever. If there is a Greek exit from the Eurozone, I think the German elite will be quite pleased that they can then use that to restructure the Eurozone and make it a zone where only strong countries are allowed in. There would then be two tiers within the European Union, which is in fact already happening. But you cannot simply get rid of German control by raising the specter of the Third Reich. That’s ahistorical.

Interview taken from The European website

June 23, 2015

Tariq Ali interviewed by Dialogos Radio about the political situation in Greece

An interview with renowned scholar, author, and analyst Tariq Ali, on the political events in Greece and Europe, his views of the first months of the SYRIZA-led government, and his upcoming visit to Greece.

To listen to the interview visit the Dialogos Radio website.

June 18, 2015

June 10, 2015

April 21, 2015

My hero: Eduardo Galeano

In Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo, the eponymous antihero is confronted by his student, who is livid that the great man has recanted: “Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero.” Galileo’s response is calm: “Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.” And he continues to work on his manuscript, which he then hands to his estranged pupil, who realises at the end of the play that what is really important has been achieved. The ideas will survive. My late friend and comrade, the Uruguayan journalist and historian Eduardo Galeano, who died this week, never recanted his beliefs in private or in public. Nor did he believe in heroes.

His entire work is suffused with the idea of mass democracy, whereby the poor and oppressed achieve self-emancipation through common action for limited or broader goals. Galeano was a modern-day Simón Bolívar, trying to achieve with his pen what the liberator had attempted with the sword: the unity of their continent against empires old and new. He spoke for the underground voices of the continent when US-backed military dictatorships crushed democracy in most parts of South America; he spoke for those being tortured, for indigenous people crushed by the dual oppression of empire and creole oligarchs.

Was he optimistic or pessimistic? Both, often together, but he never gave up hope. The right to dream, he insisted, should be inscribed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. That remained strong all his life. It is visible in his lyrical works on South American history. History written as poetry, three volumes of vignettes, each of them a pearl that went to make a stunning necklace. It is there in his journalism from Marcha in 1960s Uruguay to La Jornada in Mexico today. He was never dogmatic, always open to new ideas.

After the tyranny of the military dictatorships he realised that the armed road had been a disaster, that the Cuban revolution could not be imitated blindly. The birth of new social movements and the Bolivarian victories were both a source of inspiration and concern. He did not want to see old mistakes repeated. Whenever we met this was very strong in him. We were not simply defeated by the enemy, he would insist, but also, to a certain extent, by ourselves. Revolutionaries are not infallible.

Taken from the Guardian.

March 24, 2015

#ilovemalcolm: Tariq Ali on Malcolm X at Oxford

March 3, 2015

The Time Is Right for a Palace Revolution – Interview with Chris Hedges

PRINCETON, N.J.—Tariq Ali is part of the royalty of the left. His more than 20 books on politics and history, his seven novels, his screenplays and plays and his journalism in the Black Dwarf newspaper, the New Left Review and other publications have made him one of the most trenchant critics of corporate capitalism. He hurls rhetorical thunderbolts and searing critiques at the oily speculators and corporate oligarchs who manipulate global finance and the useful idiots in the press, the political system and the academy who support them. The history of the late part of the 20th century and the early part of the 21st century has proved Ali, an Oxford-educated intellectual and longtime gadfly who once stood as a Trotskyist candidate for Parliament in Britain, to be stunningly prophetic.

PRINCETON, N.J.—Tariq Ali is part of the royalty of the left. His more than 20 books on politics and history, his seven novels, his screenplays and plays and his journalism in the Black Dwarf newspaper, the New Left Review and other publications have made him one of the most trenchant critics of corporate capitalism. He hurls rhetorical thunderbolts and searing critiques at the oily speculators and corporate oligarchs who manipulate global finance and the useful idiots in the press, the political system and the academy who support them. The history of the late part of the 20th century and the early part of the 21st century has proved Ali, an Oxford-educated intellectual and longtime gadfly who once stood as a Trotskyist candidate for Parliament in Britain, to be stunningly prophetic.

The Pakistani-born Ali, who holds Pakistani and British citizenships, was already an icon of the left during the convulsions of the 1960s. Mick Jagger is said to have written “Street Fighting Man” after he attended an anti-war rally in Grosvenor Square on March 17, 1968, led by Ali, Vanessa Redgrave and others outside the U.S. Embassy in London. Some 8,000 protesters hurled mud, stones and smoke bombs at riot police. Mounted police charged the crowd. Over 200 people were arrested.

Ali, when we met last week shortly before he delivered the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture at Princeton University, praised the street clashes and open, sustained protests against the state that erupted during the Vietnam War. He lamented the loss of the radicalism that was nurtured by the 1960s counterculture, saying it was “unprecedented in imperial history” and produced the “most hopeful period” in the United States, “intellectually, culturally and politically.”

“I cannot think of an example of any other imperial war in history, and not just in the history of the American empire but in the history of the British and French empires, where you had tens of thousands of former GIs and sometimes serving GIs marching outside the Pentagon and saying they wanted the Vietnamese to win,” he said. “That is a unique event in the annals of empire. That is what frightened and scared the living daylights out of them [those in power]. If the heart of our apparatus is becoming infected, [they asked] what the hell are we going to do?”

This defiance found expression even within the halls of the Establishment. Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings about the Vietnam War openly challenged and defied those who were orchestrating the bloodshed. “The way that questioning was conducted educated a large segment of the population,” Ali said of the hearings, led by liberals such as J. William Fulbright. Ali then added sadly that “such hearings could never happen again.”

“That [spirit is what the ruling elite] had to roll back, and that they did quite successfully,” he said. “That rollback was completed by the implosion of the Soviet Union. They sat down and said, ‘Great, now we can do whatever we want. There is nothing abroad, and what we have at home—kids protesting about South America and Nicaragua and the contras—is peanuts. Gradually the dissent decreased.” By the start of the Iraq War, demonstrations, although large, were usually “one-day affairs.”

“It was an attempt to stop a war. Once they couldn’t stop it, that was the end,” he said about the marches opposing the Iraq War. “It was a spasm. They [authorities] made people feel there was nothing they could do; that whatever people did, those in power would do what they wanted. It was the first realization that democracy itself had been weakened and was under threat.”

The devolution of the political system through the infusion of corporate money, the rewriting of laws and regulations to remove checks on corporate power, the seizure of the press, especially the electronic press, by a handful of corporations to silence dissent, and the rise of the wholesale security and surveillance state have led to “the death of the party system” and the emergence of what Ali called “an extreme center.” Working people are being ruthlessly sacrificed on the altar of corporate profit—a scenario dramatically on display in Greece. And there is no mechanism or institution left within the structures of the capitalist system to halt or mitigate the reconfiguration of the global economy into merciless neofeudalism, a world of masters and serfs.

“This extreme center, it does not matter which party it is, effectively acts in collusion with the giant corporations, sorts out their interests and makes wars all over the world,” Ali said. “This extreme center extends throughout the Western world. This is why more and more young people are washing their hands of the democratic system as it exists. All this is a direct result of saying to people after the collapse of the Soviet Union, ‘There is no alternative.’ ”

The battle between popular will and the demands of corporate oligarchs, as they plunge greater and greater numbers of people around the globe into poverty and despair, is becoming increasingly volatile. Ali noted that even those leaders with an understanding of the destructive force of unfettered capitalism—such as the new, left-wing prime minister of Greece, Alexis Tsipras—remain intimidated by the economic and military power at the disposal of the corporate elites. This is largely why Tsipras and his finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, bowed to the demands of European banks for a four-month extension of the current $272 billion bailout for Greece. The Greek leaders were forced to promise to commit to more punishing economic reforms and to walk back from the pre-election promise of Tsipras’ ruling Syriza party to write off a large part of Greece’s sovereign debt. Greece’s debt is 175 percent of its GDP. This four-month deal, as Ali pointed out, is a delaying tactic, one that threatens to weaken widespread Greek support for Syriza. Greece cannot sustain its debt obligations. Greece and European authorities will have to collide. And this collision could trigger a financial meltdown in Greece, see it break free from the eurozone, and spawn popular upheavals in Spain, Portugal and Italy.

To read the rest of the interview, visit Truthdig.

For more information about The Extreme Centre, visit the Verso website.

February 24, 2015

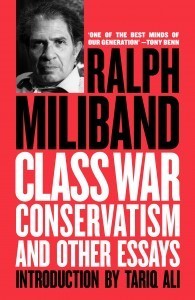

‘There was music in his delivery’ – Extract from the Introduction to Ralph Miliband’s Class War Conservatism

Ralph Miliband was a socialist intellectual of great integrity. He belonged to a generation of socialists formed by the Russian revolution and the second world war, a generation that dominated leftwing politics for almost a century. His father, a leather craftsman in Warsaw, was a member of the Jewish Bund, an organisation of militant socialist workers that insisted on preserving their ethnic autonomy.

Ralph Miliband was a socialist intellectual of great integrity. He belonged to a generation of socialists formed by the Russian revolution and the second world war, a generation that dominated leftwing politics for almost a century. His father, a leather craftsman in Warsaw, was a member of the Jewish Bund, an organisation of militant socialist workers that insisted on preserving their ethnic autonomy.

Poland, after the first world war, was beset by chaos, disorder and a foolish incursion by the Red Army, which helped to produce the ultra-nationalist military dictatorship of General Pi?sudski. There were large-scale migrations. One of Ralph’s uncles had gone eastwards and joined the Red Army, then under Trotsky’s command. His parents had left Warsaw separately in 1922. They met in Brussels, where they had both settled, and were married a year later. Ralph was born in 1924.

The years that lay ahead would be bleak. Hitler’s victory in Germany in 1932, followed by the Spanish civil war, polarised politics throughout the continent. It was not possible for an intellectually alert 15-year-old to remain unaffected. Ralph joined the lively Jewish-socialist youth organisation Hashomeir Hatzair (Young Guard), whose members later played a heroic role in the resistance.

It was here that the young Miliband learned of capitalism as a system based on exploitation, in which the rich lived off the harm they inflicted on others. One of his close friends, Maurice Tran, who was later hanged at Auschwitz, gave him a copy of The Communist Manifesto. Even though he was not yet fully aware of it, he had become enmeshed in the business of socialist politics.

Chief petty officer Ralph Miliband Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Chief petty officer Miliband. Photograph: Michael Newman/Ralph Miliband and the Politics of the New Left

In 1940, as the German armies began to roll into Belgium, the Milibands, like thousands of others, prepared to flee to France. This proved impossible because of German bombardment. Just as well; Vichy France, with the complicity of large swaths of French citizens, would later send many Jews to the camps. So Ralph and his father walked to Ostend and boarded the last boat to Dover, which was already packed with fleeing diplomats and officials. The family was divided. His mother and younger sister, Nan, remained behind, and only survived the war with the help of the Resistance.

Ralph and his father arrived in London in May 1940. Both worked, for a time, as furniture removers, helping to clear bombed houses and apartments. It was Ralph who determined the division of labour, ensuring that his main task was to carry the books. Often he would settle on the front steps of a house, immersed in a volume.

His passion for the written word led him to the works of Harold J Laski. He read that Laski taught at the London School of Economics (then exiled in Cambridge) and became determined to study there. His English was getting better by the day and, after his matriculation, he finally found his way to the LSE. Laski became a mentor, never to be forgotten.

Miliband interrupted his studies for three years from 1943 to serve as a naval rating in the Belgian section of the Royal Navy. Aware of the fact that many of his Belgian comrades were engaged in the war against fascism, and traumatised by the absence of his mother and sister, he had volunteered, using Laski’s influence to override the bureaucracy. He served on a number of destroyers and warships, helping to intercept German radio messages. He rose to the rank of chief petty officer and was greatly amused on one occasion when his new commanding officer informed him how he, Ralph, had been rated by a viscount who had commanded the ship on which he had previously served: “Miliband is stupid, but always remains cheerful.”

After the war, he graduated from the LSE with a PhD and embarked on a long academic career. He taught first at Roosevelt College in Chicago and later became a lecturer in political science at the LSE, later still a professor at Leeds. This was followed by long stints at Brandeis and New York. In the late 60s and 70s, he was in great demand at campuses throughout Britain and North America. He winced at some of the excesses (“Why the hell do you have to wear these stupid combat jackets?” I remember him asking a group of us during a big meeting on Vietnam in 1968), but remained steadfast.

A Miliband speech was always a treat: alternately sarcastic and scholarly, witty and vicious, but rarely demagogic. At a teach-in on Vietnam in London in 1966, he roared in anger: “Our leftwing friends in the PLP [Parliamentary Labour Party] tell us that they cannot force a vote on the Labour government’s shameful support for the imperialist war in Vietnam because Labour only has a tiny majority. They do not want to bring the government down. Bring it down and let honest politicians arise.” Everyone knew the Conservatives would back the government on Vietnam, but it was the mendacity of some on the Labour left that angered him.

A demonstrator outside the Daily Mail offices responds to its attack on Ralph Miliband Facebook Twitter Pinterest

A demonstrator outside the Daily Mail offices responds to its attack on Ralph Miliband. Photograph: Sang Tan/AP

Apart from a brief spell in the Labour party, he belonged to no organisation. His fierce independence excluded the Communist party. His dislike of posturing and sterile dogma kept him away from the far-left sects. This turned out to be a strength: he was unencumbered by any party line, which made his speeches refreshing. There was music in his delivery.

Advertisement

As a writer, he deployed a wide political culture and clarity of argument. Two of his books, Parliamentary Socialism (1969) and The State in Capitalist Society (1972), became classics during the 60s and 70s. As he lay dying in hospital, it gave him great pleasure to feel the proofs of his last work, Socialism for a Sceptical Age (1994). His wife, Marion, and his two sons, David and Edward, had read the first draft of the book. He had not accepted all of their criticisms and suggestions, but the process had stimulated him. The family had made him very happy.

His death on 21 May 1994 left a gaping void in a time difficult for socialists everywhere. And there we might have left it, privately bemoaning the fact that the Miliband name is now known largely because of the political fame acquired by his sons. Ironically, it was the election of Ed Miliband as leader of the Labour party that revived a discussion on his father’s political philosophy.

In October 2013, the Daily Mail decided to launch an assault on the reputation of Ralph Miliband in order to punish and discredit his son. This operation, masterminded by the tabloid’s editor – a reptile courted assiduously in the past by both Tony Blair and Gordon Brown – backfired sensationally. It was designed to discredit the son by hurling the “sins of the father” on the head of his younger son. They did so by reprinting a few sharp observations scribbled by Ralph during the second world war after listening to people conversing with each other on the Tube.

Taken out of context, these were presented as the views of someone who “hated Britain”. Ed Miliband’s response united most of the country behind him, and against the tabloid. Ralph, had he been alive, would have found the ensuing consensus extremely diverting.

Political theorist Harold Laski Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Political theorist Harold Laski had a great influence on Miliband. Photograph: Associated Newspapers/Rex

The Tories and Lib Dems made their distaste for the Mail clear; on the BBC’s Newsnight, Jeremy Paxman held up old copies of the Mail with its pro-fascist headlines (“Hurrah for the Blackshirts”, the best remembered); two former members of Thatcher’s cabinet defended Miliband père, with Michael Heseltine reminding citizens that it was the Soviet Union and the Red Army that made victory against the Axis powers possible in the first place; and an opinion poll commissioned by the Sunday Times revealed that 73% supported Ed Miliband against the Rothermere rag.

Ralph was fiercely independent-minded and could be equally scathing about left-wing verities (he spoke very sharply to me in the 70s when I suggested that world revolution was not a utopian concept) as about those of social democracy. His key work on Britain was Parliamentary Socialism (1961), in which he referred to the “sickness of labourism”, leaving no doubt as to where he stood. And later he was prescient on what the future might hold given the collapse of the broad left, writing in 1989: “We know what this immense historic process is taken to mean by the enemies of socialism everywhere: not only the approaching demise of communist regimes and their replacement by capitalist ones, but the elimination of any kind of socialist alternative to capitalism. With this intoxicating prospect of the scarcely hoped-for dissipation of an ancient nightmare, there naturally goes the celebration of the market, the virtues of free enterprise and greed unlimited. Nor is it only on the right that the belief has grown in recent times that socialism, understood as a radical transformation of the social order, has had its day: apostles of ‘new times’ on the left have come to harbour much the same belief. All that is now possible, in the eyes of the ‘new realism’, is the more humane management of a capitalism [that] is in any case being thoroughly transformed.”

His political views were far removed from those of his sons, and pretending otherwise is foolish. Ralph was not a one-nation conservative who believed in parcellised “social justice”. He remained a staunch anti-capitalist socialist till the end of his life. He was extremely close to both his sons, and was proud of their success, as any other migrant refugee would be – his kids have done well in a foreign land – but not in a political sense at all. He loathed New Labour, and in our last conversations described Blair as “Teflon man”. Neither he nor Marion (an equally strong-minded socialist and feminist) ever tried to inflict their politics on the children. Given his short temper, I wonder whether this self-denying ordinance would have survived the Iraq war. I doubt it.

And what of patriotism? In an imperialist or post-imperialist country, is it any different from national chauvinism, jingoism, etc? Does it have the same connotation in an occupied nation as in the occupying power? Many decades ago, I was quizzed by three journalists on Face the Press on Tyne Tees TV in Newcastle. The most rightwing of them, Peregrine Worsthorne from the Sunday Telegraph, annoyed by what I was saying, interrupted me: “Does the word patriotism have any meaning for people like you?”

“No,” I replied. “In my eyes, a patriot is little more than an international blackleg.”

Taken aback, he muttered: “Rather a good phrase.”

In fact, I had pinched it from Karl Liebknecht, the German socialist, explaining his vote against war credits in the German parliament in 1914.

Ralph Miliband, like many anti-fascists, joined the armed forces during the second world war. He opposed the wars in Korea and Vietnam, and spoke loudly and clearly against the Falklands expedition.

Ralph was always grateful (his word) that Britain offered him and his father, Jewish refugees fleeing occupied Belgium, asylum in 1940. Despite that, he remained an outlier, a stern critic of the British ruling elite and its institutions as well as the Labour party and its trade-union knights and peers. “The failure of social democracy,” he wrote, “implicates not only those responsible for it … Because of it, the path is made smoother for would-be popular saviours, whose extreme conservatism is carefully concealed beneath a demagogic rhetoric of national renewal and social redemption, garnished, wherever suitable, with an appeal to racial and any other kind of profitable prejudice.”

If this was the case in the 60s and 70s, his views on the Blairite version would have become more and more ferocious had he lived for another decade.

‘Renationalise the railways. Cut military spending. Argue with whoever says it can’t be done’ Interview in the Observer

Tariq Ali is recalling a party for the late Tony Benn on the House of Commons terrace shortly after Labour’s 1997 election victory. “Edward Miliband, as he was known then, came up to me, eyes shining, very excited, asking: ‘Tariq, what would you do if you had just won?’ I said: ‘The first thing I would do is to renationalise the railways. Between 70 and 80% of the people want that, it would be very popular.’ And he rolled his eyes in despair at me.”

That Milibandian eye roll was, for Ali, a symbolic moment: it typified how the current Labour leader had snapped into line with the Blairite betrayal of the social democratic principles of the party that, under Clement Attlee, had created the NHS and nationalised the commanding heights of the economy – the very principles that Ed’s father Ralph Miliband stood for.

Indeed, in his introduction to a new collection of Ralph Miliband’s writing, called Class War Conservatism and Other Essays, Ali quotes his anti-capitalist socialist intellectual friend approvingly on the nature of that betrayal. “The failure of social democracy implicates not only those responsible for it,” wrote Ralph Miliband. “Because of it the path is made smoother for would-be popular saviours, whose extreme conservatism is carefully concealed beneath a demagogic rhetoric of national renewal and social redemption.”

Ralph Miliband, who died in 1994, did not live to see New Labour in power, still less Ed or David rise through its ministerial ranks, but Tariq Ali suspects he wouldn’t have enjoyed the sight. “His political views were far removed from those of his sons, and pretending otherwise is foolish,” writes Ali. “He was extremely close to his sons, proud of their success, as any other migrant refugee would be – his kids have done well in a foreign land – but not in a political sense at all. He loathed New Labour and in our last conversation described Blair as ‘Teflon man’. Neither he nor his wife, Marion – an equally strong-minded socialist and feminist – ever tried to inflict their politics on their kids. Given his short temper, I wonder whether this self-denying ordinance would have survived the Iraq war. I doubt it.”

Tariq Ali with Ralph Miliband and Tamara Deutscher Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Tariq Ali with Ralph Miliband and Tamara Deutscher in 1989. Photograph: Michael Newman/Merlin Press

Nor did Ralph Miliband live to witness New Labour’s U-turns over nationalisation. In his new book, The Extreme Centre: A Warning, Ali recalls how, in the early 1990s, John Prescott and Frank Dobson promised to overturn John Major’s sell-off of British Rail. “Let me make it crystal clear,” said Prescott, the future Labour deputy leader, “that any privatisation of the railway system that does take place will, on the arrival of a Labour government, be quickly and effectively dealt with … and returned to public ownership.”

As you’ll have noticed, that didn’t happen. Once in power, New Labour continued the Tories’ neoliberal agenda. Today, Labour promises “public control” of the rail network. But it falls some way short of the version of “red Ed” that is lodged in the popular imagination, and which Ali wishes was a reality.

Another source of shame, he writes, came in the spectacle of New Labour ministers “celebrat[ing] the party’s startling change of register in 1997 by enriching themselves”. There’s a section in the book called “The Trough”, in which Ali lists those new Labour ministers who, after office, profited by advising or serving as directors of firms that benefit from privatisation of healthcare and private finance initiatives. The likes of Alan Milburn, Charles Clarke, Patricia Hewitt and Tony Blair (whose fortune Ali estimates to be between £40m and £60m) parlayed democratic political office into private fortunes, he contends. “The symbiosis of big money and minimalist politics has reached unprecedented heights.”

The unprincipled U-turns, the grubby symbiosis, and what Ali calls “Tweedledum-Tweedledee” party politics have alienated the electorate, he argues, and made us feel democracy as practised in Westminster is a peculiarly sick version of what it was supposed to be: rule by and for the people. Ali has a plan to change all that.

“You can’t just wait for something to happen. You have to do something,” says the 71-year-old, removing the splendid Red Army sheepskin coat he bought a long time ago in New York for $75, after having pictures taken in the garden of his home in Highgate, north London. “I suggest a charter of demands. Try to get a million signatures, starting now in 2015. Then march en masse to parliament and present the demands to the Speaker. Doesn’t matter who’s in power.” He calls it the Grand Remonstrance of the People of England.

The last Grand Remonstrance, you may recall, took place on 1 December 1641, when the English parliament presented a list of 204 grievances to Charles I about the way he was running the country. It was followed by civil war and the beheading of the king, and, as one of the greatest history books about that era was entitled, the world turned upside down.

Ali is proposing something similar, perhaps minus the beheading. What would his Grand Remonstrance contain? “Renationalising the railways and most of the utilities – gas, water, electricity. Just take them back. Argue with whoever says that can’t be done. Cut down military spending, reduce this absurd notion that Britain is a big player on the world stage – it isn’t.”

Ali’s initiative is borne of exasperation with the English. He’s tired of contrasting the exciting political cultures of Scotland and Greece, and the Bolivarian social democracies of South America, with the inert English, supine in the face of democratic deficit and neoliberal austerity. “It’s such a simple idea. I think lots and lots of young people would be interested, and it would unite people who are not engaged in politics, and some who are but don’t know what to do.”

There’s nothing so intolerable to Ali as disengagement: his life has been one of unremitting political enthusiasm. In the 1960s, the Pakistani-born, Oxford-educated leftist writer and film-maker quickly became an iconic figure of the New Left, a writer for the socialist Black Dwarf newspaper, a leading figure in the Trotskyist International Marxist Group, one of the signatories, along with the Beatles, of a petition calling for marijuana to be legalised, and so synonymous with radical demos (such as the one outside the US embassy in London against the Vietnam war in 1968) that he, reportedly, became the inspiration for the Rolling Stones’ Street Fighting Man. In the 1970s he stood as a Trotskyist candidate for parliament. He has written 20-plus books on history and politics, plus novels and screenplays. When he talks, the left listens.

Last year he was in Scotland, and found a political culture north of the border that made him sorrowful that he had the misfortune to live south of it. He argues that England in general, and Westminster in particular, is dominated by what he calls the extreme centre. What does that mean? “It is the political system that has grown up under neoliberalism. It has existed in the States for at least a century and a half, where you have two political parties with different clientele but funded by the same source, and basically carrying out the same policies,” says Ali. “This system has now extended to Europe.”

What’s extreme about the extreme centre? “It backs the American wars and it attacks its own people through austerity. It believes in surveillance on a level we have never seen before, it puts civil liberties under threat, it renditions people – a polite word meaning that people are kidnapped and handed over for torture. People talk about the extreme left and the extreme right, but the real danger today is from the extreme centre.”

Such policies are partially responsible for the terrorist attacks in Paris and Copenhagen, the rise of Islamophobia and antisemitism, he argues. “State security services know this better than our political leaders. Did you know more young Muslims are employed by the state security services in Britain, France and Germany than work for al-Qaida and Isis? So they must give the security services a pretty good image of what the mood in the community is – and they say again and again that the reason for this radicalisation is the wars Britain and the US are fighting in the Muslim world You go out and fight wars and commit brutalities that make individual terrorist brutalities pale by comparison. How can you expect people not to be radicalised? They have no other way of expressing their anger. And they become terrorists.”

A few days after our interview, I email Ali to ask him about the killings in Copenhagen. What prompted a radical Muslim to kill a participant at a free speech debate and a guard at a synagogue? Ali responds quickly: “Am in the States, where Copenhagen is overshadowed by the Chapel Hill killings [the murder of three Muslim students in North Carolina earlier this month]. A non-religious fundo kills three Muslim students. A jihadi known to Danish intelligence does his business. The violence springs from the chaos of a disordered world.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are no Je suis Charlie stickers on the windows of Ali’s Highgate home. Heroising the murdered Charlie Hebdo staff, as French president François Hollande did, is inimical to Ali. “I knew the magazine in the late 60s, and it was very radical – they were banned by the French government for making fun of De Gaulle the day after he died. In the 80s it had become a stale magazine, and people have told me that one reason for attacking the Muslims and reprinting the Danish cartoons was to boost circulation.” He argues that Je suis Charlie stickers express something other than support for freedom of expression and condemnation of those who murdered in the name of Islam – a loathing for Muslims.

Why, then, does he think Islamophobia, if that’s what it is, is on the rise in Europe? “This is a very straightforward example of finding scapegoats because you don’t want to admit that what you’re doing is partially responsible.” And those he thinks partially responsible for the rise in Islamist terrorism in Europe are the politicians of the extreme centre. Ali cites a recent article in French magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, in which one of Charlie Hebdo’s founders, Henri Roussel, contended that French foreign policy is largely to blame for the attack on the magazine. Ali agrees: “Hollande makes wars in countries where he doesn’t need to, to replace someone who’s bad with someone who’s equally bad. You see this in Libya, you see this in Syria, you see this with Isis.”

As in France, so in Britain. It follows that one reason Ali favours a Grand Remonstrance is to create a mass movement in England that would emulate what Syriza has done in Greece and Podemos in Spain – thereby taking on the the extreme centre and revivifying democratic politics. It’s from such grassroots movements that Tariq Ali hopes that the extreme centre will be destroyed.

He certainly has no hope that the general election will do much but change Tweedledum for Tweedledee. “That’s why young people around the country aren’t voting, and why people such as Russell Brand have an appeal. Younger people have been disabused of tribal loyalties to party that are more likely to afflict older people.” He’ll be voting Green. Why? “Because the Green candidate here is an old comrade from the 60s, a trade union activist, anti-war, rock solid on most issues. Why should I bother voting for anyone else?”

He expects Ed Miliband to form the next government, but, because Labour is likely to be trounced in Scotland (“the SNP may well get 80% of the Scottish vote, so Labour heartlands like Glasgow will fall to them”), Ali reckons Miliband will only be able to do so with support from another party. But neither the SNP nor the LibDems, the most likely coalition partners, would be easy for Miliband to work with: Labour spent last year bitterly campaigning against the former, and has spent the past five years denouncing the collaboration of the latter with the Tories’ governmental austerity policies. “In any case, it’s not going to be back to politics as normal.”

Just before we finish, Ali tells me of something that made him despair in London recently: the sight of union jacks flying at half-mast after the Saudi king died. “That was Britain on its knees before big money. It was grotesque and so plain and simple.” Perhaps it was, but many didn’t even notice them, still less understand whose death was being mourned and the ritual abasement the lowered flags symbolised. If Ali wants to awaken England from its apolitical slumbers, he has his work cut out.

• The Extreme Centre is published by Verso at £7.99

Source: Observer

Tariq Ali's Blog

- Tariq Ali's profile

- 798 followers